Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Old Testament Essays

On-line version ISSN 2312-3621

Print version ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.26 n.3 Pretoria Jan. 2013

The blame game: prophetic rhetoric and ideology in Jeremiah 14:10-16

Willie J. Wessels

University of South Africa

ABSTRACT

There are clear signs in the book of Jeremiah of conflict between the prophet Jeremiah and other prophetic groups in the Jerusalem set-ting. Some of the more prominent passages reflecting this conflict are Jer 23:9-40 and 27-28. However tension between the prophets also surfaces in Jer 14:10-16. In the first instance the technical detail of the text is discussed. The text is scrutinised with an interest in the rhetoric employed in this passage, but also to address the clashes in ideological viewpoints between the various parties. Sec-ondly a coherent reading of 14:10-16 is presented, highlighting both the rhetorical strategies employed in the composition of the text and the ideas promoted in this passage. The conclusion reached is that the voice of the composer of the text dominates. Furthermore when it comes to blame, people and prophets alike should take their share of the blame for the alienation from Yahweh and the devastating result of the exile.

A INTRODUCTION

There are clear signs in the book of Jeremiah of conflict between the prophet Jeremiah and other prophetic groups in the Jerusalem setting. Some of the more prominent passages reflecting this conflict are Jer 23:9-40 and 27-28. However tension between the prophets also surfaces in Jer 14:13-16. The aim of this article is first to analyse the text with an interest in the rhetoric employed in this passage,1 but also to address the clashes in ideological viewpoints between the various parties.2 In the first part of the article close attention is paid to the detail of the text and is an analytical endeavour. The second main section is an attempt to read the text coherently, highlighting both the rhetorical strategies employed in the composition of the text and the ideas promoted in this passage.

B DISCUSSION

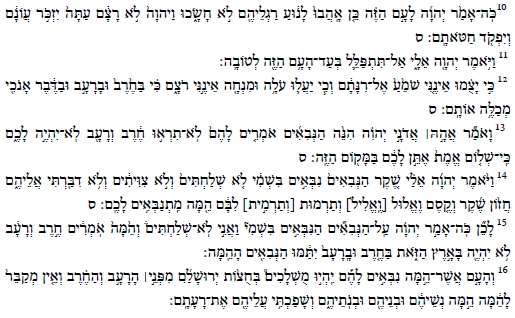

Jeremiah 14:10-16 WTT:

The focus of this article is Jer 14:13-16. This passage can however not be discussed in isolation, we need to pay attention to the broader context of the chapter and the book of Jeremiah. Most commentators would agree that a new section starts in ch. 14 of Jeremiah and that it continues up to the end of 17:27. When it comes to the finer division of the various sections that form this text unit in the book of Jeremiah, there is clearly no consensus. Again most commentators would agree that 14:1-15:4 forms a workable unit within the larger section already mentioned above.3 It is however not surprising that no two scholars agree on the subdivisions of the unit 14:1-15:4. Some scholars have an eye for the finer detail and would therefore divide the unit into many smaller units whilst others who prefer broader categories would have fewer subdivisions. Schmidt4 for instance divides the bigger unit 14:1-15:4 into two subsections, again subdivided into 1 (14:1; 14:2-6; 14:7-9; 14:10-12; 14:13-16) and 2 (14:17-18; 14:19-22; 15:1-4). In his view the section should be subdivided then into seven subsections. Carroll5 subdivides 14:1-15:4 into vv. 1-6 (drought); 79 (communal lament); 10-12 (divine response to lament); 13-16 (false security condemned); 17-18 (bemoans the fate of people); 19-22 (communal lament); 15:1-4 (judgement oracle). Another attempt to divide a bigger unit into sensible subsections is that of Lundbom6 who subdivides 14:1-15:21 into 14:1-6 (Judah are in mourning); 14:10-16 (judgement and no mediation); 14:17-19b (crying) and 14:19c-15:3. Some of the scholars who prefer to work with broader divisions are for instance Brueggemann and Allen. Brueggemann7 divides 14:115:4 into vv. 1-10 (a lament poem); 11-16 (a prose prophetic interruption); 1722 (a lament speech) and 15:1-4 (four destroyers). Allen8 also works with a larger unit 14:1-17:27 which he subdivides into 14:1-16 (unanswered prayers) and 14:17-15:9 (more unanswered prayers) as two of the main subsections of interest to this article. It is clear from the examples mentioned above that there are many different ways of looking at the broader unit. Some of the subsections are obvious and scholars show agreement in this regard, but when it comes to finer details there is clearly no agreement which leaves room for yet some more suggested divisions.

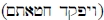

As mentioned already, the main concern of this article is with 14:13-16. The more important question is whether these verses should be seen as a separate section or part of a larger section. Schmidt 9 works with vv. 13-16 as a unit under the heading "Jeremias reagierendes Wort" and so does Carroll.10 There are however those who start the unit with v. 1011 and others with v. 11.12. My submission is that although the focus of this article will be on vv. 13-16, it should be read in conjunction with vv. 10-12. Some help is offered in this regard in the Masoretic text by looking at the structural indicators such as the setuma after vv. 9, 10, 12 and 14. The section 14:7-9 seems to be poetic in style and is so printed in the Masoretic text. It is not clear whether v. 10 is poetic or prose and views differ in this regard.13 Scholars agree that vv. 11-16 is a prose section and it is also printed accordingly in the Masoretic text.

To strengthen arguments for the structural divisions proposed in the previous paragraph, the contents should also be considered. The section preceding 14:10-16 clearly forms part of a lament which is interrupted by 10-16.14 As Brueggemann15 has indicated, v. 17 again resumes a section with a lamenting tone. I do not agree with Brueggemann that v. 10 should be regarded as part of 14:1-9 and I will argue in my exposition of the contents of 10-16 why this is the case.

A closer look at 14:10-16 reveals an emphasis on the verb "to say." Verse 10 is introduced with the words "thus said Yahweh to this people." This is followed in v. 11 with "and Yahweh said to me" and "then I said" in v. 13, "and Yahweh said to me" in v. 14 and finally in v. 15 "therefore thus said Yahweh concerning the prophets." The words of Yahweh in v. 10 are about the people of Judah. In v. 11, which is a response to v. 10, Yahweh instructs the prophet Jeremiah how he should respond to the people. In reaction to Yahweh's instruction in v. 11 the prophet has something to say in v. 13 about the prophets opposing his views. In response to what the prophet has to say, Yahweh again addresses the prophet in v. 14. Verse 15 is introduced with  as concluding response by Yahweh first concerning the prophets, but then also the people. Whereas the people were addressed in v. 10, so again they are addressed in v. 16 and so structurally render support for the view that 10-16 should be regarded as a unit. From the brief observation above, it seems that a dialogue style is used to convey the content of the message in this passage.

as concluding response by Yahweh first concerning the prophets, but then also the people. Whereas the people were addressed in v. 10, so again they are addressed in v. 16 and so structurally render support for the view that 10-16 should be regarded as a unit. From the brief observation above, it seems that a dialogue style is used to convey the content of the message in this passage.

C ANALYSIS OF 14:10-16

Jeremiah 14:10 is introduced by the prophetic formula "so says Yahweh." What Yahweh has to say is about16 "this people," meaning the people of Judah. The next part of the sentence is introduced with כן, an adverb particle that serves the function of a colon. The statement or declaration Yahweh makes about this people is the following: the verb "to love" (אהב ) is followed by ל particle preposition plus נוע (to wander) verb qal infinitive construct and then the noun "feet" with third person masculine plural suffix followed by the verb third person plural "did not restrain." This bicolon17 emphasises the graveness of their transgression for which Yahweh holds them accountable. The next part of the sentence (a tricolon) shows the consequences (ל particle conjunction plus יהוה noun proper) of the way they have conducted their lives by stating that Yahweh does not accept them ("Yahweh has not given them his approval")18. In a parallelism it is stated that Yahweh will now "remember the iniquity"

and "call to account their sin"

and "call to account their sin"  .19 The third person plural suffixes refer to the people who are the focus of Yahweh's message. The structure of the verse and the stylistic devices employed indicate that this verse should be regarded as poetic in composition.20

.19 The third person plural suffixes refer to the people who are the focus of Yahweh's message. The structure of the verse and the stylistic devices employed indicate that this verse should be regarded as poetic in composition.20

The next few prose vv. 11-16 respond to the poetic v. 10 and is in the style of a dialogue between Yahweh and the prophet, supposedly Jeremiah. In v. 11 the prophet reveals what Yahweh has said to him. In the jussive form of the verb, the prophet is commanded not to pray for the good or welfare  of "this people."21 Verse 12 is introduced by the particle

of "this people."21 Verse 12 is introduced by the particle  with the meaning "when" or "though." This particle is repeated three times in this verse, in all three instances introducing negative sentences. Although the people show penance by first of all fasting, in the first person singular Yahweh says he will not listen to them. And although they offer burnt offerings and cereal offerings to show their remorse, Yahweh again in the first person singular says he will not accept these offerings. The third use of

with the meaning "when" or "though." This particle is repeated three times in this verse, in all three instances introducing negative sentences. Although the people show penance by first of all fasting, in the first person singular Yahweh says he will not listen to them. And although they offer burnt offerings and cereal offerings to show their remorse, Yahweh again in the first person singular says he will not accept these offerings. The third use of  in v. 12 has the meaning of "but" or "indeed." Yahweh in first person singular says he will literally "finish them" or "consume them," or as Lundbom translates

in v. 12 has the meaning of "but" or "indeed." Yahweh in first person singular says he will literally "finish them" or "consume them," or as Lundbom translates  (verb pi'el ptc. m. sg. Abs.) - "Iam putting an end to them."22 Yahweh will consume them or put an end to them by means of the stock phrase "by sword and famine and by pestilence." This phrase occurs several times in the book of Jeremiah in longer or shorter versions (Jer 21:9; 27:8; 32:36; Ezek 14:21). In each of these instances there is a waw between the words. In a slightly different manner the same three words appear with the ך (waw) only between the last two words (Jer 29:18; 38:2; 42:17; 42: 22; 44:13; Ezek 6:11). The shorter version of the phrase that only mentions sword and famine appears in Jer 14:13; 15 and in the inverted sequence of famine in sword only in v. 16. This is a phrase therefore that only occurs in the book of Jeremiah and in the book of Ezekiel. The meaning of this phrase will be discussed at a later stage in this article.

(verb pi'el ptc. m. sg. Abs.) - "Iam putting an end to them."22 Yahweh will consume them or put an end to them by means of the stock phrase "by sword and famine and by pestilence." This phrase occurs several times in the book of Jeremiah in longer or shorter versions (Jer 21:9; 27:8; 32:36; Ezek 14:21). In each of these instances there is a waw between the words. In a slightly different manner the same three words appear with the ך (waw) only between the last two words (Jer 29:18; 38:2; 42:17; 42: 22; 44:13; Ezek 6:11). The shorter version of the phrase that only mentions sword and famine appears in Jer 14:13; 15 and in the inverted sequence of famine in sword only in v. 16. This is a phrase therefore that only occurs in the book of Jeremiah and in the book of Ezekiel. The meaning of this phrase will be discussed at a later stage in this article.

After the setuma at the end of the first 12 verses, the verb "to say" again follows the prophet addressing Yahweh (v. 13). With an interjectory particle  the prophet responds to Yahweh's command by introducing the opposing prophets as the focus of the next verses. These prophets are said to have negated the condemning words from Yahweh. Their message to the people is expressed by two negations namely "they will not see"

the prophet responds to Yahweh's command by introducing the opposing prophets as the focus of the next verses. These prophets are said to have negated the condemning words from Yahweh. Their message to the people is expressed by two negations namely "they will not see"  and "there will not be" or "they will not experience"

and "there will not be" or "they will not experience"  sword and famine. These negations are followed by a

sword and famine. These negations are followed by a  particle expressing contrast. Instead of sword and famine the people will receive "true peace" in "this place"

particle expressing contrast. Instead of sword and famine the people will receive "true peace" in "this place"  . This is a reference to the city Jerusalem. 23 The expression "true peace" is somewhat unique and a few manuscripts suggest rather "truth and peace." This is suggested because of the occurrence of the expression "truth and peace" in Jer 33:6. It is however difficult on the scantiness of the evidence to make the suggested change. What is strange in this verse is the fact that Jeremiah refers to the prophets in the plural who have a message for the people of Judah, but v. 13 ends with a first person singular verb "I will give" to you (second person plural suffix) true peace. This can only be explained if Jeremiah is quoting the direct words that the prophets claimed Yahweh said.

. This is a reference to the city Jerusalem. 23 The expression "true peace" is somewhat unique and a few manuscripts suggest rather "truth and peace." This is suggested because of the occurrence of the expression "truth and peace" in Jer 33:6. It is however difficult on the scantiness of the evidence to make the suggested change. What is strange in this verse is the fact that Jeremiah refers to the prophets in the plural who have a message for the people of Judah, but v. 13 ends with a first person singular verb "I will give" to you (second person plural suffix) true peace. This can only be explained if Jeremiah is quoting the direct words that the prophets claimed Yahweh said.

Verse 14 is again introduced by the verb "to say." Yahweh is the subject of the verb and the prophet is quoting Yahweh's response to what the prophet Jeremiah reported in v. 13. What is important as far as the syntax of this sentence is concerned, is the placement of the word "deceit"  before mentioning to whom this noun is referring. This is clearly a case of putting emphasis on the fact that the prophets are lying prophets. The noun deceit/ lie

before mentioning to whom this noun is referring. This is clearly a case of putting emphasis on the fact that the prophets are lying prophets. The noun deceit/ lie  is often used in the book of Jeremiah and is a key term in Jeremiah's conflict with opposing prophets.24 Another important point worth mentioning is the use of the expression "in my name"

is often used in the book of Jeremiah and is a key term in Jeremiah's conflict with opposing prophets.24 Another important point worth mentioning is the use of the expression "in my name"  . This expression in the first person singular appears in Deut 18:19, 20 and then exclusively in Jer 12:16; 14:14, 15; 23:25; 27:15; 29:9, 21, 23. All these mentioned references concern the definition of a true prophet. The next important key phrase in v. 14 is "I did not send them, nor did I command them"

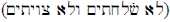

. This expression in the first person singular appears in Deut 18:19, 20 and then exclusively in Jer 12:16; 14:14, 15; 23:25; 27:15; 29:9, 21, 23. All these mentioned references concern the definition of a true prophet. The next important key phrase in v. 14 is "I did not send them, nor did I command them"  . This exact expression also appears in 23:32. The shorter form of the expression where only the verb "send" is applied appears in 14:15; 23:21; 27:15; 29:9, 31; see also 28:9, 15.The shorter and the longer form of the expression is not that important, what is important is that all the places where this reference surfaces have to do with true and false prophecy. Another important aspect of this verse to take note of is how the final part of this sentence is structured. The verb part of the sentence appears right at the end, which shifts the focus to what precedes the verb. This is clearly structured in a way to emphasise what the real issue at stake is. Again the emphasis is on deceit or falseness of the vision in the first place, then worthless divination and finally the deceit of their own minds. The sentence is clearly structured to emphasise the deceitfulness of every means that the opposing prophets use as sources of revelation. Jeremiah 14:14 mentions visions in the negative sense of the word, describing them as deceitful. The form of the word for vision

. This exact expression also appears in 23:32. The shorter form of the expression where only the verb "send" is applied appears in 14:15; 23:21; 27:15; 29:9, 31; see also 28:9, 15.The shorter and the longer form of the expression is not that important, what is important is that all the places where this reference surfaces have to do with true and false prophecy. Another important aspect of this verse to take note of is how the final part of this sentence is structured. The verb part of the sentence appears right at the end, which shifts the focus to what precedes the verb. This is clearly structured in a way to emphasise what the real issue at stake is. Again the emphasis is on deceit or falseness of the vision in the first place, then worthless divination and finally the deceit of their own minds. The sentence is clearly structured to emphasise the deceitfulness of every means that the opposing prophets use as sources of revelation. Jeremiah 14:14 mentions visions in the negative sense of the word, describing them as deceitful. The form of the word for vision  occurs at the following places in the OT: 1 Sam 3:1; Prov 29:18; Isa 1:1; 29:7; Jer 14:14; 23:16; Lam 2:9; Ezek 7:13, 26; 12:22, 23, 24; 13:16; Dan 1:17; 8:1; 9:24; 10; 11:14; Hos 12: 11; Obad 1:1; Nah 1:1 and Hab 2:2, 3. Of these references the two in Jeremiah appear in a negative sense of the word, and so do the ones in Ezek 7:26; 12:22, 24; 13:6. There seems to be no negative sentiment when it comes to the idea of a vision in the book of Daniel. In Isa 1:1, Obad 1:1 and Nah 1:1 the revelations these prophets received from Yahweh are classified as visions coming from Yahweh. It therefore seems that round about the time of the exile, visions seemed to be under suspicion as a means of revelation.

occurs at the following places in the OT: 1 Sam 3:1; Prov 29:18; Isa 1:1; 29:7; Jer 14:14; 23:16; Lam 2:9; Ezek 7:13, 26; 12:22, 23, 24; 13:16; Dan 1:17; 8:1; 9:24; 10; 11:14; Hos 12: 11; Obad 1:1; Nah 1:1 and Hab 2:2, 3. Of these references the two in Jeremiah appear in a negative sense of the word, and so do the ones in Ezek 7:26; 12:22, 24; 13:6. There seems to be no negative sentiment when it comes to the idea of a vision in the book of Daniel. In Isa 1:1, Obad 1:1 and Nah 1:1 the revelations these prophets received from Yahweh are classified as visions coming from Yahweh. It therefore seems that round about the time of the exile, visions seemed to be under suspicion as a means of revelation.

Jeremiah 14:14 also refers to worthless divination. In this regard it is of significance to note what Deut 18:10 reads: "No one shall be found among you who makes a son or daughter pass through fire, or who practices divination..." (nrs). This is a clear denunciation of the opposing prophets. Divination is also regarded negatively in Num 23:23; 1 Sam 15:23 and Ezek 21:26. Another concept used to put the opposing prophets in a negative light, is the reference to "a deceit of their mind." The word deceit in this form is used only four times of which three appear in the book of Jeremiah. In Jer 8:5 it simply refers to "deceit," whilst in 14:14 at 23:26 it is used in combination with heart (bL), literally meaning "the deceit of their heart." The only other instance of interest is the reference to Zeph 3:13 where it refers to deceitful tongues. Of importance therefore are the two uses in Jer 14:14 and 23:26 which are similar and both concern conflict with other prophets.

Verse 15 is introduced with  followed by the prophetic formula "so says Yahweh," indicating what the consequences will be of Yahweh's intervention. The objects of concern are the prophets, with a clear indication of who they are and what they have said to deserve Yahweh's verdict. Interestingly in v. 13 the reference was to "this place," meaning Jerusalem, but now the reference is to "in this land," which means the land of Judah. The word combination "sword and famine" is repeated twice in this verse.

followed by the prophetic formula "so says Yahweh," indicating what the consequences will be of Yahweh's intervention. The objects of concern are the prophets, with a clear indication of who they are and what they have said to deserve Yahweh's verdict. Interestingly in v. 13 the reference was to "this place," meaning Jerusalem, but now the reference is to "in this land," which means the land of Judah. The word combination "sword and famine" is repeated twice in this verse.

Following  which appears in v. 15, a second target group is referred to in v. 16, namely the people. Again the verse is structured in such a manner that by introducing the sentence with "the people"

which appears in v. 15, a second target group is referred to in v. 16, namely the people. Again the verse is structured in such a manner that by introducing the sentence with "the people"  it is clear where the emphasis lies. The word combination of "sword and famine" is in the reverse order "famine and sword" in this verse.25 The verb "to bury" is also referred to in this sentence. It seems that the pi'el form of the verb has the meaning of a mass burial or to burying many at once.

it is clear where the emphasis lies. The word combination of "sword and famine" is in the reverse order "famine and sword" in this verse.25 The verb "to bury" is also referred to in this sentence. It seems that the pi'el form of the verb has the meaning of a mass burial or to burying many at once.

D A COHERENT READING OF JEREMIAH 14:10-16

The aim of this article is to focus on the rhetoric of the chosen passage from the book of Jeremiah and also the ideological issues that might surface in the reading process.

At first the idea was to start the exposition of this passage from v. 13, but from the analysis of the structure, the content and in terms of the question of blame it became clear that the exposition should start at v. 10. The blame game already starts in v. 10 where Yahweh speaks about the people of Judah. It also seems that v. 10, which I regard as a poetic verse, initiated the responses in vv. 11-16.26 The narrator of this verse, presumably the prophet Jeremiah, is reporting on what Yahweh had to say about the people and his response to theirwandering actions. Thompson27 describes the style as autobiographical, whilst Willis28 sees it as a dialogue between the prophet and his audience. It should be noted that the people themselves are not addressed, but it is conveyed what Yahweh says concerning them. It is not clear who the people are that the prophet is addressing.29 By talking about the people and not with them creates an impersonal atmosphere and a sense of distance.30 The fact that the audience is difficult to identify also makes it difficult to date the dialogue.31 It is also possible that this prophetic communiqué was intended for the post-exilic community who had their own concerns with salvation.32 The first two lines of v. 10 simply state that this people, a reference to the people of Judah, love to wander with no set boundaries. What Yahweh had to say is that the people are wandering uncontrollably. What follows on this statement of Yahweh, is the prophet spelling out Yahweh's reaction and the consequences for the people because of their wandering. The third line qualifies the previous two lines (a bicolon) as negative acts, because what the wandering actions imply make the people unacceptable to Yahweh. The next two lines of the tricolon reveal that Yahweh will now remember their iniquity and in parallel to that, call to account their sin. The implication is that the wandering is nothing less than acts of sin and most probably implies disloyalty to Yahweh because of worship of foreign gods.33 This assumption finds support from similar wording in Hos 8:13 where reference is made to Israel's transgression of worshipping foreign gods. The prophet therefore conveys what he understands Yahweh's reaction to the wandering of his people to be. Yahweh's response to their wandering (disloyalty) is expressed in three strong verbs: not to accept34 them, to remember their iniquity and to call to account their sin. In terms of the interest of this article by addressing the issue of blame, v. 10 puts the blame for Yahweh's estranged relationship with the people of Judah squarely on the shoulders of the people themselves.

If 14:10-16 is read in conjunction with the previous passage 14:7-9, the expectation was that a salvation oracle should follow on the confession of sin spelled out in v. 7. What the people of Judah received was an oracle of judgement and a God distancing himself from his people.35 But this is not where the reporting or announcing activity of the speaker (prophet) ends, he still had to inform his audience what Yahweh still had to say to them. It is important for what is to follow to note that an innocent remark that Yahweh spoke to him as prophet, is not so innocent. When it comes to the so-called false prophets, Yahweh is quoted to have said that he did not speak to these prophets. By this introduction "Yahweh said to me," the implication is that he (Jeremiah) is a true prophet, the real deal.

Whereas v. 10 reported on what Yahweh had to say about the people and their share of the blame in Yahweh's disinterest in them, in v. 11 Yahweh is addressing Jeremiah himself. The conversation is now in prose style. Jeremiah is reporting what Yahweh had to say to him about this people he spoke of in v. 10. The prophet presents what Yahweh had to say in the form of a direct quotation which starts in v. 11 and continues to the end of the v. 12. A setuma is placed at the end of v. 12. The prophet states that Yahweh directly commanded him not to pray on behalf of this people for good to happen to them.36 This reference to "the good" for the people is not accidental, but is important in terms of what is to follow of "false prophets" proclaiming messages of "true peace," by implication what is really good for the people.

It is interesting to observe the role of the prophet in this whole drama he is reporting on. He was the one spelling out the judgement of Yahweh because of the wandering of the people. He was the one who announced that Yahweh does not accept the people any longer, not even their confession of sins in 14:7. It is he who expresses the message of alienation and rejection. Verse 11 however addresses that mediator role Jeremiah is willing to take on by interceding on behalf of the people to Yahweh. In the drama he is portrayed as the willing person to pray for the people, but it is Yahweh who puts a stop to his willingness. Jeremiah is therefore not to blame as unwilling to act on behalf of the people of Judah. The prophet continues in vv. 11-12 by quoting Yahweh's direct words. It is Yahweh himself who commanded him not to pray. Yahweh's words are also quoted in v. 12 how he will respond to any rituals and offering presented to him by the people.

To emphasise his dissatisfaction with his people and his estrangement from them, Yahweh says that no ritual or cultic practice will sway him to take a new stand towards them or to pardon them. It is said that if they fast Yahweh will not listen to their cry, and when they offer burnt offerings and cereal offerings, he will not accept them.37 The wording of these two verses spells out rejection. Whereas in the past the people could make amends by approaching Yahweh showing remorse by fasting and by bringing burned and cereal offerings, it is no longer regarded as a means to restore the broken covenant relationship. But the prophet is quoting Yahweh to say that it does not end with not accepting or rejecting cultic practices, it goes much further. Yahweh has lost his patience with them, what is in store is annihilation and the end of the road for them. A phrase well known in the book of Jeremiah is used to express the finality of the relationship between Yahweh and the people of Judah. By sword and famine and by pestilence he will make an end of them. Again the rhetoric is as sharp as a sword and as devastating as famine and the consequences of both war and lack of food and water- pestilence! Jeremiah says Yahweh has communicated to him that he has reached the end of his patience and can no longer be manipulated or swayed to restore the relationship. The prophet therefore is only voicing what Yahweh has communicated to him. It is Yahweh's words, not the prophet's words. In terms of rhetoric, quoting Yahweh as first person speaker renders both validity and authenticity to the prophetic proclamation.

Although the prophet communicated the devastating news that the end is coming for the people of Judah, the dialogue is continued in v. 13. In this verse the prophet (speaker) responds to what Yahweh had to say in the preceding vv. 10-12. As was the case in v. 10, it was surely expected that an oracle of salvation would follow the attempt of the people to mend the relationship with Yah-weh by bringing offers and showing remorse. However this was not the case, instead the good news to be announced by the prophets is nothing less than deceit. In terms of blaming the people as responsible for the dire situation in Judah, in Jeremiah's view Yahweh should look no further than the prophets.38 Jeremiah is presented here as the champion for the people, since he tries to convince Yahweh that the people should not be blamed39 for the estranged relationship with Yahweh, but the "false" prophets.

In addressing Yahweh, Jeremiah conveys to Yahweh what the prophets claimed his words to the people of Judah were. Jeremiah is therefore quoting the words of the prophets they pretended to be Yahweh's words to the people.40 With a cry of distress Jeremiah quotes the prophets voicing Yahweh's words: "you shall not see sword, and famine shall not come to you; indeed true (assured) peace I will give you in this place." The reference to the first person singular who will give true peace is a referral to Yahweh. Therefore the proph-ets41 pretend to speak the direct words of Yahweh to the people. However what these prophets say Yahweh has revealed to them is not true.

It is important to notice in terms of the rhetoric strategy employed here, that when Jeremiah reveals in v. 11 what Yahweh said to him about the people, he quotes the words of Yahweh. Now in v. 13 Jeremiah is blaming the prophets that what they say comes directly from Yahweh is deceitful and untrue. What these prophets say is contradictory to the message he (Jeremiah) received from Yahweh in v. 11. Both contingents of prophets are therefore claiming to speak on behalf of Yahweh, but the text presents Jeremiah as the narrator and his words are the true words from Yahweh. It however should not go unnoticed that the speaker whose view is presented here, has the power of the position as narrator. As the narrator Jeremiah is reporting ideas and views which he claims come from Yahweh, but at the same time he is reporting what the opposition prophets say Yahweh has revealed to them. And as speaker he quite emphatically communicates that their words are untrue and nothing less than deceit. The voice of the speaker which is supposedly Jeremiah, is the voice the Jeremiah tradition is promoting in the text. As mentioned, in the text Jeremiah is also the voice that expresses the views of the opposing prophets. What this boils down to is that the words and views of these prophets have been filtered through the voice of the prophet Jeremiah of the tradition.

It seems from v. 13 that Jeremiah is incriminating other prophetic groups before Yahweh as promoting a wrong theology and thereby misleading the people of Judah. The blame should therefore not so much be on the people but on the prophets who give false revelation pretending it is from the mouth of Yahweh. This verse clearly reflects Jeremiah's attack on the royal/Zion theology which resulted in false security. In the first place these prophets proclaim a salvation oracle from Yahweh countering the threat of war and famine accompanying circumstances of war. Secondly, the oracle also promises not only peace, but true peace.42 The disputing of the shalom theology is a constant theme throughout the book of Jeremiah and a major issue of conflict between Jeremiah and other prophetic groups.43 This shalom theology was attractive to the Kings and their administrations and was promoted by groups such as the Zadokite priests and prophets such as Hannaniah and other Yahwistic prophets. The third component of the royal/Zion theology is the reference to Jerusalem. In v. 13 there is mention of "this place"  , which some interpret as a reference to the city Jerusalem, but others as referring to the temple.44 This all ties in with the promise to the Davidic lineage that there will always be a king on the throne Jerusalem, that Yahweh will reside in the Temple in Zion and because of this they will experience peace and security.45 In Jeremiah's view this shalom theology promoted by some prophetic groups is the root of all evil in Judah and responsible for the complacent attitude of the people of Judah. To Jeremiah and in particular the tradition of Jeremiah the promise of 2 Sam 7 should be regarded as conditional in nature. To claim Yahweh's presence requires undivided loyalty to Yahweh and obedience of the stipulations of the book of law and the covenant. Loyalty to Yahweh requires ethical obligations of caring for justice and righteousness, of caring for the widow, the orphan and the poor and above all worship of Yahweh only. Royal/Zion theology became nothing less than an ideology that endangered the relationship with Yahweh that had far-reaching consequences to the kingship and people of Judah. Verse 13 therefore reveals one of the fundamental differences between Jeremiah and other prophetic groups.

, which some interpret as a reference to the city Jerusalem, but others as referring to the temple.44 This all ties in with the promise to the Davidic lineage that there will always be a king on the throne Jerusalem, that Yahweh will reside in the Temple in Zion and because of this they will experience peace and security.45 In Jeremiah's view this shalom theology promoted by some prophetic groups is the root of all evil in Judah and responsible for the complacent attitude of the people of Judah. To Jeremiah and in particular the tradition of Jeremiah the promise of 2 Sam 7 should be regarded as conditional in nature. To claim Yahweh's presence requires undivided loyalty to Yahweh and obedience of the stipulations of the book of law and the covenant. Loyalty to Yahweh requires ethical obligations of caring for justice and righteousness, of caring for the widow, the orphan and the poor and above all worship of Yahweh only. Royal/Zion theology became nothing less than an ideology that endangered the relationship with Yahweh that had far-reaching consequences to the kingship and people of Judah. Verse 13 therefore reveals one of the fundamental differences between Jeremiah and other prophetic groups.

The dialogue continues in v. 14 with Jeremiah as the speaker saying that Yahweh had the following to say to him and then he quotes the words from the mouth of Yahweh. Again the rhetoric technique is applied of quoting direct words from Yahweh to emphasise the authenticity of what is reported here. As was mentioned earlier, the syntax of the sentence places the emphasis on the idea of deceit  . A literal translation would be the following: "a lie the prophets are prophesying in my name." Not only is the emphasis placed on prophesying lies to the people, but these people have the audacity according to the text of Jeremiah to do that in the name of Yahweh.46 To speak in the name of Yahweh implies to speak on his authority. The text wants to emphasise the seriousness of speaking lies and to do that claiming false authority for the words by linking them to Yahweh's name. But if that is not enough, some of the prophets are blamed for speaking without being commissioned to do so. In an expression which often occurs in the conflict between Jeremiah and other prophetic groups, it is stated in the first person singular that Yahweh says: "I did not send them, and I did not command them, and I did not speak to them." According to Jeremiah these prophets failed the test of being true prophets by not been commissioned by Yahweh. In both chs. 23:21 and 29:9 in the book of Jeremiah this commission is required in order to claim to be a true prophet. In contrast to these prophets Jeremiah in the passage under discussion made the point that Yahweh spoke to him, implying therefore that he is a true prophet commissioned by Yahweh to speak. In terms of Yahweh's own word then, Jeremiah is a legitimate prophet.

. A literal translation would be the following: "a lie the prophets are prophesying in my name." Not only is the emphasis placed on prophesying lies to the people, but these people have the audacity according to the text of Jeremiah to do that in the name of Yahweh.46 To speak in the name of Yahweh implies to speak on his authority. The text wants to emphasise the seriousness of speaking lies and to do that claiming false authority for the words by linking them to Yahweh's name. But if that is not enough, some of the prophets are blamed for speaking without being commissioned to do so. In an expression which often occurs in the conflict between Jeremiah and other prophetic groups, it is stated in the first person singular that Yahweh says: "I did not send them, and I did not command them, and I did not speak to them." According to Jeremiah these prophets failed the test of being true prophets by not been commissioned by Yahweh. In both chs. 23:21 and 29:9 in the book of Jeremiah this commission is required in order to claim to be a true prophet. In contrast to these prophets Jeremiah in the passage under discussion made the point that Yahweh spoke to him, implying therefore that he is a true prophet commissioned by Yahweh to speak. In terms of Yahweh's own word then, Jeremiah is a legitimate prophet.

In Jer 23:18, 22 an additional criterion is mentioned and that is to be in the "Council" of Yahweh. This means to be in Yahweh's presence, to hear him and to receive his words which they should then proclaim to the people. If this is not enough to prove the point that these prophets are false and deceitful, three further reasons are mentioned why the blame for all the misery in Judah should be attributed to the opposing prophets. It is said that these prophets offer lying visions, worthless divination47 and the deceit of their own minds (cf. 23:26). The rhetoric applied in this verse to denounce these prophets as false is to strategically accumulate reason upon reason why all the blame should be for their account. These prophets are illegitimate because they have no commission, they pretend to be true prophets, they are deceitful, their means of receiving revelation are false. What they proclaim is words from their own minds, their message of peace is untrue and then they have the audacity to do it on authority of Yahweh. The Jeremiah tradition leaves no doubt in the minds of the audience or audiences engaging the text of Jeremiah that the prophets who opposed Jeremiah, were false prophets, full of deceit and lies.

This short passage is concluded in 14:15-16 with a judgement statement. The message commenced in v. 10 with a judgement oracle and ends again with a judgement announcement.48 The concluding verdict to the foregoing dialogue is introduced with  followed by what Jeremiah reports Yahweh is saying about these opposing prophets and the people of Judah. Yahweh's verdict on the prophets commences with the repetition of what was said about these prophets in v. 14: "they prophesy in my name although I did not send them." And to drive the point even further the direct words of the prophets are quoted again "sword and famine shall not come on this land." This almost artificial and superfluous repetition of words is a rhetorical ploy to leave no doubt who these prophets are and why they are to be discredited. But it also has the function of emphasising the verdict to follow, namely: "by sword and famine those prophets shall be consumed." The verdict on the prophets is that the reverse of the false message they have proclaimed to the people of Judah will happen to them. This judgement on the prophets not only describes the fate of the opposing prophets, but also serves the purpose of vindicating Jeremiah as the true prophet of Yahweh. Jeremiah has the "privilege" to announce the verdict on Yahweh's behalf. Again the power of the narrator is illustrated in this passage. There is only one voice and it is the voice that the tradition affords the prophet Jeremiah.49

followed by what Jeremiah reports Yahweh is saying about these opposing prophets and the people of Judah. Yahweh's verdict on the prophets commences with the repetition of what was said about these prophets in v. 14: "they prophesy in my name although I did not send them." And to drive the point even further the direct words of the prophets are quoted again "sword and famine shall not come on this land." This almost artificial and superfluous repetition of words is a rhetorical ploy to leave no doubt who these prophets are and why they are to be discredited. But it also has the function of emphasising the verdict to follow, namely: "by sword and famine those prophets shall be consumed." The verdict on the prophets is that the reverse of the false message they have proclaimed to the people of Judah will happen to them. This judgement on the prophets not only describes the fate of the opposing prophets, but also serves the purpose of vindicating Jeremiah as the true prophet of Yahweh. Jeremiah has the "privilege" to announce the verdict on Yahweh's behalf. Again the power of the narrator is illustrated in this passage. There is only one voice and it is the voice that the tradition affords the prophet Jeremiah.49

Verse 16 follows the same style of giving feedback of Yahweh's verdict on the people of Judah. These people who took the words of the false prophets to heart will experience a terrible fate. The judgement on them is that they will be thrown into the streets of Jerusalem as a consequence of famine and sword, meaning consequences of war. But more that, they will be disgraced, they will suffer the humiliation that no one will bury them.50 In actual fact there will be no people left behind to see to the proper burial of the people of Judah. To further emphasise the total annihilation of the people of Judah and to leave no uncertainty, the judgement is that the person and all his descendants will be wiped out. The rhetoric of stating the father, his wife, his sons and his daughters will all die again serves the purpose of emphasising the finality of their fate. There will be no person to perform the burial duty. Then as the final nail in the coffin an announcement, which refers back to v. 10, is made: "for I will pour out upon them their wickedness." Whereas Jeremiah wanted to pin the blame for everything on the prophets, the final verdict of Yahweh is that the prophets are to be blamed, but the people will still suffer the consequences of their own transgressions and disloyalty.51 The people cannot shift the blame to the prophets alone, for they willingly listened to the false prophets.52 People should be able to discern when prophecies are false, because they are supposed know what the covenant stipulates.53 The rhetoric is also employed to create an aversive effect on the audiences sympathetic to the shalom ideology. Jeremiah appeals to the imagination of people by painting gruelling pictures of the consequences they will suffer by adhering to false prophecy.

The question can be asked whether Jeremiah is corrected by Yahweh on the blaming of the prophets or whether it is a rhetorical tactic to blame all the parties. The answer seems to be that it is a strategy to distribute the blame on prophets and people alike. As narrator of the section, the prophet has the control over the flow of the dialogue and the ideological view promoted. What might seem to be a correction of the prophet's view is to present the final verdict as coming from Yahweh; he is simply the commissioned messenger to do so.

E CONCLUSION

A chiastic structure binds the section 14:10-16 together on who is to blame for the misery of Judah. The people are first mentioned (A), then follows words on the prophets (B). When the verdict is announced, first the prophets are in focus (B) followed by the words on the fate of the people of Judah (A). The verdict of the narrator is that the prophet Jeremiah cannot pin the blame on the prophets alone, the people should look no further than themselves if someone is to blame. The only party that comes unscathed out of the blame game is the prophet Jeremiah. This is the ideological position awarded him by the Jeremiah tradition who portray him as the one to whom Yahweh speaks and who is entrusted with delivering the judgement oracles and verdicts from Yahweh. He is the one who was willing to mediate and pray for the people, but Yahweh prevented him from doing so. It was he who tried to convince Yahweh that the false prophets should be blamed for misleading the ordinary people. And although he succeeded in pinning some guilt on them, in the end both prophets and people have to take responsibility for Yahweh's rejection of the people of Judah and the fate of both city and land.

It is also clear that the root of the problem is the Zion theology promoted by the prophets and practised by the people of Judah. The prophets are blamed for abusing both Yahweh and the people with their lies and deceit. The people are likewise blamed for becoming complacent because of their understanding of the Zion theology. The false security and violation of the covenant stipulations affected their relationship with Yahweh. It resulted in them having divided loyalties by worshiping foreign gods and pursuing foreign alliances.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allen, Leslie C. Jeremiah: A Commentary. Old Testament Library. Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2008. [ Links ]

Brueggemann, Walter. A Commentary on Jeremiah: Exile & Homecoming. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998. [ Links ]

Carroll, Robert P. Jeremiah: A Commentary. Old Testament Library. London: SCM., 1986. [ Links ]

Clines, David J. A. Interested Parties: The Ideology of Writers and Readers of the Hebrew Bible. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2009. [ Links ]

Craigie, Peter C., H. Kelly Page and Joel F. Drinkard, Jr. Jeremiah 1-25. Word Biblical Commentary. Dallas: Word Books, 1991. [ Links ]

Diamond, A. R. Pete. "Jeremiah." Pages 543-559 in Eerdmans' Commentary on the Bible. Edited by James D. G. Dunn and John W. Rogerson. Grand Rapids:Eerdmans, 2003. [ Links ]

Fischer, Georg. Jeremia 1-25: Übersetzt und ausgelegt. Freiburg: Herder, 2005. [ Links ]

Huey, F. B., Jr. Jeremiah, Lamentations. Nashville, Tenn.: Broadman Press, 1993. [ Links ]

Kiss, Jenö. Die Klage Gottes und des Propheten, Ihre Rolle in der Komposition und Redaktion von Jer 11-12, 14-15 und 18. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, 2003. [ Links ]

Lange, Armin. Vom prophetischen Wort zur prophetischen Tradition: Studien zur Traditions- und Redaktionsgeschichte innerprophetischer Konflikte in der Hebräischen Bibel. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2002. [ Links ]

Lundbom, Jack R. Jeremiah 1-20: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. New York: Doubleday, 1999. [ Links ]

Mitchell, Margaret M. "Rhetorical and New Literary Criticism." Pages 615-633 in The Oxford Handbook of Biblical Studies. Edited by John W. Rogerson and Judith M. Lieu. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006. [ Links ]

Overholt, Thomas W. The Threat to Falsehood: A Study in the Theology of the Book of Jeremiah. London: SCM, 1970. [ Links ]

Rudolph, Wilhelm. Jeremia. 3rd improved ed. Tübingen: JCB Mohr, 1968. [ Links ]

Schmidt, Werner, Das Buch Jeremia: Kapitel 1-20. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2008. [ Links ]

Sharp, Carolyn J. Prophecy and Ideology in Jeremiah: Struggles for Authority in the Deutero-Jeremianic Prose. London: T & T Clark, 2003. [ Links ]

Thiel, Winfred. Die deuteronomistische Redaktion von Jeremia 1-25. Wissenschaftliche Monographien zum Alten und Neuen Testament 41. Neukirchen: Neukirchener Verlag, 1973. [ Links ]

Thompson, John A. The Book of Jeremiah. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1980. [ Links ]

Weiser, Arthur. Das Buch Jeremia. Göttingen: Vanderhoeck & Ruprecht, 1969. [ Links ]

Wessels, Wilhelm J. "So They Do Not Profit This People at All" (Jer 23:32): A Critique of Prophecy." Verbum et Ecclesia 32 (2011): 11-7. [ Links ]

Willis, John T. "Dialogue Between Prophet and Audience as Rhetorical Device in the Book of Jeremiah." Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 33 (1985): 63-82. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Prof. Wilhelm J. Wessels

Department of Old Testament and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

University of South Africa

P. O. Box 392, Unisa, 0003

Email: wessewj@unisa.ac.za

1 Margaret M. Mitchell, "Rhetorical and New Literary Criticism," in The Oxford Handbook of Biblical Studies (ed. John W. Rogerson and Judith M. Lieu; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 615-633, offers a good overview on rhetorical criticism in both the OT and the NT. The term rhetorical criticism is used not in the technical sense of a refined methodology, but as a reading strategy. The attempt is to offer a close reading of the text with an understanding that the text is composed to engage audiences (readers) to reflect on matters and even convince them of ideas promoted. The text is treated with respect as a religious text embedded within history.

2 David J. A. Clines, Interested Parties: The Ideology of Writers and Readers of the Hebrew Bible (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2009), 9-25 gives an insightful discussion of the various ways the concept ideology is understood and used. In this article the concept is used to refer to an idea or a set of ideas held and promoted by an individual or a group.

3 Armin Lange, Von prophetischen Wort zur prophetischen Tradition: Studien zur Traditions- und Redaksionsgeschichte innerprophetischer Konflikte in der Hebräischen Bibel (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2002), 194; Peter C. H. Craigie, H. Kelly Page and Joel F. Drinkard, Jr., Jeremiah 1-25 (WBC; Dallas, Tex.: Word Books, 1991), 194-195 regard the larger unit as Jer 14:1-16:21, with 14:1-15:9 as a subunit. John A. Thompson, The Book of Jeremiah (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1980), 375 works with the larger unit 14:1-15:9. He also regards v. 10 as part of 14:110 with 11-16 as a separate unit.

4 Werner Schmidt, Das Buch Jeremia: Kapitel 1-20 (Gottingen: Vandenhoeck &Ruprecht, 2008), 258-274.

5 Robert P. Carroll, Jeremiah: A Commentary (OTL; London: SCM, 1986), 306320.

6 Jack R. Lundbom, Jeremiah 1-20: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (New York: Doubleday, 1999), 691-712.

7 Walter Brueggemann, A Commentary on Jeremiah: Exile & Homecoming (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1998), 134-143.

8 Leslie C. Allen, Jeremiah (OTL; Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox, 2008), 165-177.

9 Schmidt, Jeremia 1-20, 262.

10 Carroll, Jeremiah, 313-15.

11 Cf. Lundbom, Jeremiah 1-20, 703.

12 Allen, Jeremiah, 170.

13 Jenö Kiss, Die Klage Gottes und des Propheten, Ihre Rolle in der Komposition und Redaktion von Jer 11-12, 14-15 und 18 (Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, 2003), 89 regards the whole passage 14:10-16 as prose.

14 There is a case to be argued that 14:10-16 should be related to the broader theme in chs. 14-15 concerning the drought; See in this regard also Lange, Vom Prophetischer Wort, 196 in this regard. This is not the opportunity to investigate the idea in this article, but it should be pursued at some stage.

15 Brueggemann, Jeremiah, 138-141.

16 ל is used instead of על Craigie, Page and Drinkard, Jeremiah 1-25, 202 says; "The preposition ל normally introduces direct speech, but the people are spoken about in third person, as if the Lord can no longer stand to address them directly."

17 Lundbom, Jeremiah 1-20, 704

18 Allen, Jeremiah, 166.

19 The lxx omits these words. This is perhaps done because of haplography and should remain intact as it is in the mt, since we find the similar tricolon in Hos 8:13.

20 Some view this verse as prose. Cf. Arthur Weiser, Das Buch Jeremia (Göttingen: Vanderhoeck & Ruprecht, 1969), 119, Wilhelm Rudolph, Jeremia (3rd improved ed.; Tübingen: JCB Mohr, 1968), 98 and Craigie, Page and Drinkard, Jeremiah 1-25, 196.

21 Cf. similar prayer refusals in Jer 7:16; 11:14 and 15:1.

22 Lundbom, Jeremiah 1-20, 703.

23 Lundbom, Jeremiah 1-20, 706-707 has pointed out that scholars differ about this reference. Some possibilities mentioned are Jerusalem, the temple and even the land.

24 For a thorough discussion of  [lies or deception] in the theology of Jeremiah, see Thomas W. Overholt, The Threat to Falsehood: A Study in the Theology of the Book of Jeremiah (London: SCM, 1970), 86-104. Carolyn J. Sharp, Prophecy and Ideology in Jeremiah: Struggles for Authority in the Deutero-Jeremianic Prose. London: T&T Clark, 2003), 113 warns that this concept should not be treated in an abstract generalised way, but in the various literary contexts in which it appears. See also Wilhelm J. Wessels, "So They Do Not Profit This People at All (Jer 23:32): A Critique of Prophecy," VetE 32 (2011): 5.

[lies or deception] in the theology of Jeremiah, see Thomas W. Overholt, The Threat to Falsehood: A Study in the Theology of the Book of Jeremiah (London: SCM, 1970), 86-104. Carolyn J. Sharp, Prophecy and Ideology in Jeremiah: Struggles for Authority in the Deutero-Jeremianic Prose. London: T&T Clark, 2003), 113 warns that this concept should not be treated in an abstract generalised way, but in the various literary contexts in which it appears. See also Wilhelm J. Wessels, "So They Do Not Profit This People at All (Jer 23:32): A Critique of Prophecy," VetE 32 (2011): 5.

25 The sequence sword and famine, famine and sword form a chiasm.

26 As indicated, the view argued in this article is that not only the structure, but also the content support the idea that the theme of blame runs from vv. 10-16. I therefore disagree with Carroll, Jeremiah, 312 who works with the idea of two separate themes, the first one containing divine statements about the people in 14:10-12 and the second one in vv. 13-16 containing divine statements about the prophets. He admits that in v. 16 both these groups are addressed. Thompson, Jeremiah, 377 takes v. 10 to be part of the preceding lament poem, but do agree that 14:11-16 is directly connected to v. 10 although it is a prose section, since it arose from v. 10.

27 Thompson, Jeremiah, 377.

28 After studying several passages in the book of Jeremiah, John T. Willis, "Dialogue Between Prophet and Audience as Rhetorical Device in the Book of Jeremiah," JSOT 33 (1985): 75 concludes, "the dialogue form reflected in these texts suggests that sometimes Jeremiah actually engaged in dialogue with his audiences."

29 Schmidt, Jeremia 1-20, 263 holds the view that the references to offer practices and intercessory prayer in 14:11-12 are an indication of a liturgical situation. He asks the following interesting and significant question: "Spiegelt sich in der Struktur von Jer 14 f eine gottesdienstliche Abfolge wider, nämlich eine Volksklagefeier aus Anlass einer Dürre?" Did Jeremiah act as prophetic speaker at such a confession occasion? The rhetorical situation is not spelled out nor is it clear. It might be that in an exilic/post-exilic context words from Jeremiah or words ascribed to the prophet were used to address the issue of rejection and alienation from Yahweh and their land, cf. Schmidt, Jeremia 1-20, 267. Lange, Vom prophetischen Wort, 194 also mentions the liturgical elements as well as the idea of a "'Volksklagen.." Thompson, Jeremiah, 378 dates 14:11-16 in the period following the exile of 587 B.C.E.. Although he does not claim that Jeremiah is responsible for the arrangement of the material, he regards it as closely related to the prophet.

30 Weiser, Jeremia, 124-125.

31 Kiss, Die Klage Gottes, 104 argues that 14:10-12 should be dated in the early exilic period because it reflects themes and terminology from Jeremiah's circle of influence, whilst 13-16 should be dated in the late exilic period. These verses were probably adapted for the purpose of this late exilic contexts and leans strongly on Jeremiah and Ezekiel.

32 Lange, Vom prophetischer Wort, 198 observed the almost identical wording between Jer 14:13 and Hag 2:9 referring to "peace" and "this place." He argues that this is more than co-incidental and is probably an indication of Haggai leaning on Jeremiah's words. As Lange says, "Dass es dabei tatsächlich um Heilshoffnungen geht, die mit dem Wiederaufbau des Jerusalemer Tempels verknüpft waren, erhärtet auch das Wortpaar  " The wording "truth and peace" are also used in the post-exilic verse Zech 8:19 and strengthen the idea of a rebuilding of the temple context for Jer 14:10-16, but is remains speculative. More research and substantiating arguments are needed to support this proposal.

" The wording "truth and peace" are also used in the post-exilic verse Zech 8:19 and strengthen the idea of a rebuilding of the temple context for Jer 14:10-16, but is remains speculative. More research and substantiating arguments are needed to support this proposal.

33 Cf. Amos 8:12 and Pss 59:16 and 109:10. There is no doubt in Lundbom's, Jeremiah 1-20, 705 mind that this is a reference to involvement with foreign gods. He also refers to Jer 2:23-25 and 3:2. Thompson, Jeremiah, 382 sees the reference to wandering as alluding to the many idolatrous sanctuaries and possible engagement in foreign alliances.

34 The verb "accept" is often associated with sacrificial offerings - cf. Jer 6:20; Lev 1:4; 7:18; 22:25; Deut 33:11; 2 Sam 24:23; see Carroll, Jeremiah, 312.

35 Cf. Craigie, Page and Drinkard, Jeremiah 1-25, 202. F. B. Huey, Jr., Jeremiah, Lamentations (Nashville, Tenn.: Broadman, 1993), 153 see the wandering as people shamelessly pursuing other gods and the reason for Yahweh rejecting them.

36 Jer 7:16 and 11:14 prohibits prayer for the people. There are a number of references in the Book of Jeremiah that emphasise that people should not expect the good, but rather evil (cf. Jer 21:10; 39:16 and 44:27). Thiel, Winfred. Die deuteronomistische Redaktion von Jeremia 1-25 (WMANT 41; Neukirchen: Neukirchener Verlag, 1973), 182 regards these instances as traces of Deuteronomistic involvement in the text of Jeremiah; see also Lange, Vom prophetischer Wort, 194-207 who refers to dtrJer.

37 Jer 6:19-20; 7:21-23 and 11:15 also address the issue of Yahweh's rejection of offerings and sacrifices. Cf. Lundbom, Jeremiah 1-20, 707.

38 A. R. Pete Diamond, "Jeremiah," in Eerdmans' Commentary on the Bible (ed. James G. D. Dunn and John W. Rogerson; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003), 569, refers to the fact that Jeremiah is seeking an oracle from Yahweh that would expose the opposing prophet proclaiming peace as false.

39 Cf. Thompson, Jeremiah, 377.

40 Willis, Dialogue, 75 remarks "that sometimes he used a dialogue style by putting words into the mouths of his opponents for the purpose of refuting their position, and that the redactor (or redactors) of this material portrayed that dialogue or created a dialogue as a form of his own as a means of defining clearly the distinction between what he wanted his readers to believe the view of Jeremiah to be in contrast to that which he opposed."

41 Carroll, Jeremiah, 314 calls them Yahwistic prophets.

42 The lxx has peace and truth (assurance).

43 Cf. Jer 4:10; 5:12; 6:14; 23:17; 28:5-9.

44 Weiser, Jeremia, 125 regards it as a reference to the temple, referring to modes of revelation being rejected (v. 14). In view of the build up to total rejection in the passage, Jerusalem seems to be the better option, since in v. 15 the reference is to "this land." Not only is Jerusalem in danger, but the land of Judah as a whole will suffer the consequences of alienation from Yahweh.

45 See Jer 14:9 where is said, "But you are in our midst, O Lord, and we are called by your name."

46 Georg Fischer, Jeremia: 1-25: Übersetzt und ausgelegt (Freiburg: Herder, 2005), 490.

47 Lundbom, Jeremiah 1-20, 708 mentions that the OT is negatively inclined towards divination and condemns the practice of divination; Cf. Deut 18:10; 2 Kgs 17:17; Mic 3:5-12 and Ezek 13.

48 Lundbom, Jeremiah 1-20, 703.

49 Willis, Dialogue, 75 concludes "The final redactors of the book of Jeremiah used the dialogue method to communicate his message to his readers, whether this was handed down to him from actual confrontations during the ministry of Jeremiah, or was one of the literary styles he adopted to communicate his message."

50 Thompson, Jeremiah, 383 refers to the calamitous situation of unburied corpses; Cf. Ezek 6:5; 37:1; Amos 2:1.

51 Bruegggemann, Jeremiah, 138 says: "The canon, however, votes clearly with the harsh line of Jeremiah and against a religion of easy utterances."

52 Schmidt, Jeremia 1-20, 265 has pointed out that the people of Judah have often been blamed for the Babylonian exile in late sections of the Jeremiah book as well as in the Deuteronomistic history.

53 Thompson, Jeremiah, 383.