Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Old Testament Essays

On-line version ISSN 2312-3621

Print version ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.26 n.3 Pretoria Jan. 2013

Jeremiah 33:14-26: the question of text stability and the devaluation of kingship

Johanna Erzberger

Institut Catolique de Paris1

ABSTRACT

The versions of the book of Jeremiah might be considered the result of the text's steady preservation and actualisation by its redactors. Those redactors are considered to have been part of a supporting group for which this text was significant. Using Jer 33:14-26, the most extensive of the null variants of the Masoretic Text (MT), and its biblical (in particular its intra-Jeremian) intertexts as an example, this article seeks the supporting group's worldview and frame of orientation, which expresses itself both in the redactors' modes of reworking their "Vorlage" as in the content of the changes they make. It has already been proposed (by Bogaert and Lust) that whoever was responsible for the adding of Jer 33:14-26, might also have been responsible for certain MT variants in Jer 23:5-6 and 31:35-38, which are quoted by Jer 33:14-26. The differences in the MT's mode of reworking both texts however have hardly been noticed. It is those differences which seem particularly well suited to shed light on the supporting group's relevancies and frame of orientation, according to which texts and traditions concerning the royal figure of David seem already to have gained a certain degree of text stability. The LXX frequently serves as a horizon for a better understanding of the MT's mode of reworking the text.

A PRELIMINARIES

Redaction criticism per definition assumes thematic and stylistic coherent editions of a text. Considering Jeremiah we have the rare opportunity to observe closely two versions of one biblical book with considerable differences in substance, length, and order that result from a relatively short period of time, and gives a rare insight into text history.2 None of the currently discussed positions considering the text history of the book of Jeremiah succeeds in explaining the differences between the versions of Jeremiah by their editors' reworking a pretext in a thematic and stylistic coherent way.3 It seems far more adequate to assume some elective and fragmented reworking of the text, the editions of Jeremiah might alternatively be considered as a result of the steady preserving and actualisation of a given text.

Any edition's variants are part of the interaction of their redactors with an already existing text. As this text is of relevance for a religious community, to which its redactors belong, it might be more effective and appropriate to ask for the groups which were supporting and reworking those texts.

According to Mannheim understanding takes place within distinct spaces of experience. Spaces of experience are determined by a common social, historical or religious background. Contexts of experience express themselves in frames of orientation that are characterised by certain structures of plausibility.4 The group's engagement with the given text gives evidence of the groups' values and orientations, of their worldview. The supporting groups' values and orientations are characterised both by their mode of reworking of the text and by the propositions they make.

Bohnsack, whose "documentary method of interpretation", designed as an instrument of qualitative methods in social sciences, is based on Mannheim's considerations, suggests that a group's frame of orientation shows in (text) sequences that are marked by a high degree of interactivity.5 Originally developed in connection with the interpretation of group interviews the "documentary method of interpretation" has subsequently been adapted to other text genres Following Bohnsack's methodical considerations this article concentrates on a passage where the versions differ to a relatively high degree and where modifications within several passages can be shown to be interdependent.

Jer 33:14-26 is the longest of those passages documented only by the MT. By building on variants of the MT within its immediate context it is well integrated into the MT's immediate context. Besides other biblical intertexts Jer 33:14-26 refers to two texts from the book of Jeremiah itself, Jer 23:5-6 and 31:35-37,6 which present considerable differences between the versions. Both texts are alluded to explicitly according to their MT version.7

The following analysis starts with a short introduction of Jer 33:14-26. It then concentrates on the longer and more complex of the two intertexts from the book of Jeremiah: Jer 31:31-37 (MT) // 38:31-37 (LXX) is analysed with regard to the versions' variants and mode of reworking an assumed "Vorlage."8 While variants that are likely to be attributed to the LXX can be explained as restructuring the closer text context, variants attributed to the MT are likely to have been motivated by the newly created passage Jer 33:14-26 and other biblical intertexts quoted there. The obvious differences between the MT's redactors' mode of reworking Jer 23:5-6 and Jer 31:35-37 however pose the question regarding the redactors' criteria and even more urgently so as Jer 33:14-26 contradicts central elements of the quoted text Jer 23:5-6, which the redactors left untouched in Jer 23:5-6 . As it seems to be part of the LXX's redactors' orientation to preserve an already accepted traditional text, interferences with their assumed pretext seem to be potentially less rewarding. They are nevertheless frequently brought into the discussion where they serve as a horizon for the MT's mode of reworking the text.

B JEREMIAH 33:14-26 IN THE MASORETIC TEXT

Jeremiah 33:14-26 has no equivalent in the LXX. As an announcement of salvation towards the houses of Israel and Judah (v. 14), Jer 33:14-26 announces a branch of righteousness (v. 15-16), which materialises in two figures, one royal, and one priestly. A divine promise of a future offspring from David (v. 17) is followed by a parallel promise to the Levites (v. 18). Verses 20-26 centres on the question that is pronounced by the representatives of the textual adversaries in 33:24: Is Israel a גוי? According to vv. 20-26 Israel's enduring existence as a גוי is guaranteed by God's unalienable covenant with David and the Levites.

Jeremiah 33:14-26 refers to a variety of biblical intertexts:

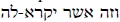

Verses 15-16 built on Jer 23:5-6. The divine promise to David (v. 17), which is explicitly introduced as a quotation:  alludes to 2 Sam 7 using formalised language

alludes to 2 Sam 7 using formalised language  of a plurality of passages in 1 Kings and 2 Chronicles (1 Kgs 2:4; 8:25; 9:5 and 2 Chr 6:16), which likewise alludes to the divine promise according to 2 Sam 7.9 The divine promise to the Levites (v. 18) follows the example of the preceding promise to David (v. 17).

of a plurality of passages in 1 Kings and 2 Chronicles (1 Kgs 2:4; 8:25; 9:5 and 2 Chr 6:16), which likewise alludes to the divine promise according to 2 Sam 7.9 The divine promise to the Levites (v. 18) follows the example of the preceding promise to David (v. 17).

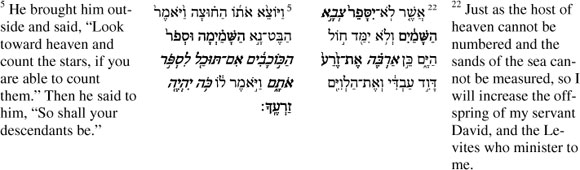

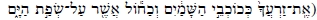

Verses 20-26 leans heavily on Jer 31:35-37, but links this inter-Jeremiah with a non-Jeremiah intertext. Alluding to Gen 15, Jer 33:22 links both the descendants (זרה) of David and the descendants (זרה) of the Levites to the promise of countless descendants to Abraham.

C JEREMIAH 38:35-37 (LXX) // 31:35-37 (MT)

1 Jeremiah 31(38):35-37 in Both Versions

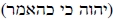

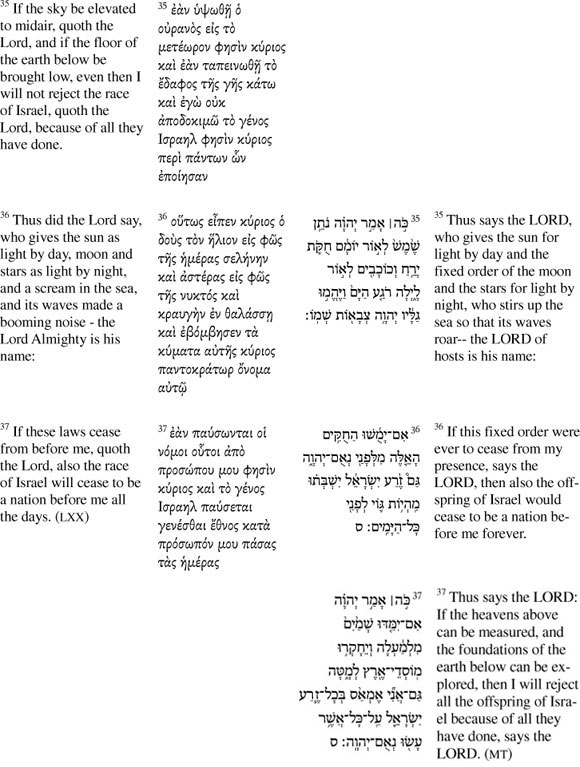

Jeremiah 33:20-25 cites Jer 31:35-37//38:35-37. Jeremiah 31:35-37 is part of the so called "Trostbüchlein." It immediately follows the well-known passage where God promises to write his Torah on his people's heart. The stability (LXX) and inaccessibility (MT) of the order of heaven and earth guarantee the stability of God's covenant with Israel. God appears as the creator of day, night and ocean. The validity of the νοµοί/חוקיס guarantees Israel's status as a nation in front of God. The passage considerably differs in the MT and the LXX with regard to order and wording.

Both versions can be divided into three subsections. The order of the sequences is changed: the first subsection in the LXX (v. 35) corresponds with the last one in the MT (v. 37). Additional differences concern variants in corresponding verses. חקת in v. 35 (MT) has no equivalent in the corresponding verse (v. 36) in the LXX. In v. 37 (LXX)//v. 36 (MT) νόµοι, which more frequently translates תורה or תורות, corresponds to חוקים. Verses 35 (LXX) and 37 (MT), which differ regarding their position within the sequence by occupying the first position in the LXX and the last in the MT, differ the most extensively.

35 If the sky be elevated to midair, quoth the Lord, and if the floor of the earth below be brought low, even then I will not reject the race of Israel, quoth the Lord, because of all they have done. (LXX)

37 Thus says the LORD: If the heavens above can be measured, and the foundations of the earth below can be explored, then I will reject all the offspring of Israel because of all they have done, says the LORD. (MT)

While ο ουρανός corresponds to שמים, το έδαφος της γης corresponds to מוסדי־ארץ. The adverbial εις το µετέωρον answers to מלצעלה. The functions of bothoth adverbials depend on the meaning of the verb, which they are subordinated to and which widely differs. Consequently the functions of the adverbials differ. מדד and חקר (both nip'al) on the one hand and ύψόω and ταπεινόω on the other seem to be neither connected with nor derived one from the other.

2 The Reorganising of the Closer Context in the Septuagint and the Masoretic Text

חוקים in 31:36 is translated by νόµοι in the LXX's corresponding v. 38:37. חוקים is not the most commonly chosen equivalent of νόµοι, νόµος usually translates as תורה. The usage of νόµοι in 38:37 or חוקים in 31:36 however establishes the verse in different ways in its context.

In the LXX νόµοι has been most recently used in Jer 38:31, where it is equivalent to the תורה in the corresponding 31:31 in the MT. As in 38:31, νόµοι is used in the plural. In the LXX νόµοι creates a link to the νόµοι in Jer 38:31, according to which God writes those νόµοι on the people's heart. There is no corresponding link in the MT. חוקיס in 31:36 does not refer to תורה in 31:31 either by wording or by number.

Within the MT תורה has a possible reference point in חקת in the preceding 31:35. Due to the fact that חקה in 31:35 and קח in 31:36 (MT) are similar but not identical, this reference is weaker than the reference between νόµοι in Jer 38:31 and 38:37 (LXX).

Considering the two translations of the two occurrences of מ לפני in Jer 31:36 as άπο προσώπου µου at one place (38:37a) and as κατά προσώπου µου (38:37b) at the other, few scholars have argued for a difference in terms of content.10 However the difference between מלפני in Jer 31:36a and לפני in 31:36b would have to be considered. Moreover κατά προσώπου µου is far closer to άπο προσώπου µου than the slightly more frequently used equivalent of לפני, εναντίον του would have been. Considering the context a difference in terms of content between the meanings of the phrase in Jer 38:37 (LXX) and Jer 31:36 (MT) may nevertheless be involved. In view of an identification of the νόµοι mentioned in 38:37 and the νόµοι written on the heart of the people according to 38:31, which is created by the above mentioned link between 38:31 and 38:37, 38:37 (LXX) might be understood as discussing Israel's existence as an έθνος according to God's standards.

3 Diachrony

As both versions can be considered to be responsible for those variants which change the overall structure of their respective close contexts by linking different textual elements, diachronical questions concerning them at first sight seem difficult to answer. There are however directions of dependency that are more likely than others.

חקת in 31:35 (MT), which has no equivalent in the corresponding v. 38:36 in the LXX,11 must either have been inserted by the MT or omitted either by the LXX or by its Hebrew pretext. While inserting חקת in v. 35 would have created a link between vv. 35 and 36, omitting the word would have broken it. The inexactness of the correspondence (חקת [v. 35] vs. חקת [v. 36]) however makes an insertion of חקת at that point less probable than a more exact correspondence would have had.

In a similar way the utilisation of one Greek term (νόµοι) in 38:37 (LXX) and 38:33 (LXX), but two different Hebrew terms (תורה and חקיס) in the corresponding vv. 31:33 (MT) and 31:36 (MT) can be explained by the LXX having created a link between both verses by translating two different Hebrew terms (תורה and חקיס) by one Greek term (νόµοι). It might equally be explained by the MT breaking the link by using two different words, תורה and חקיס, for one original Hebrew term which the LXX translated as νόµοι.

Both variants, חקה in v. 35 having no equivalent in the LXX and the utilisation of חקיס vs. νόµοι in v. 36(37), should be seen together. If the MT broke an existing link between 31:33 and 31:36 by choosing a different term in 31:36, it seems reasonable to hold the MT's redactors equally responsible for either adding חקה in v. 35 or for choosing חקיס under the influence of an already existing חקה in v. 35. In both cases the utilisation of a similar rather than exactly the same term seems disruptive. In case the LXX was to be held responsible for having created the link between 38:37 and 38:31 by using νόµοι at both places yet on the other hand, חקה in v. 36 would have lost its reference point in the חקיס in v. 37. The LXX might have easily omitted חקה after it had lost its reference point.

Weighing the pros and cons it seems more likely that the LXX's Hebrew "Vorlage" or the LXX created the link between 38:37 (LXX) and 38:33 (LXX) and that either the LXX's Hebrew "Vorlage" or consequently the LXX was responsible for the deletion of חקה in 31:35 (MT). It seems less likely that the MT established an inexact link between 31:35 (MT) and 31:36 (MT).

D JEREMIAH 31:35-37 (MT) AND 33:14-26

The semantic shift between νόµοι in 38:37 (LXX) and חקיס in 31:36 (MT) as well as חקה in 31:36 (MT) having no equivalent in the LXX can be explained by the versions' purpose of restructuring the closer context. While חקה in 31:36 creates a reference to 31:35, νόµοι in 38:37 (LXX) identifies the νόµοι which guarantees Israel's enduring existence with the νόµοι God writes on the people's heart according to Jer 38:31.

The further differences of 38:35 (LXX) and 31:37 (MT), the reshaping of order in 38:35-37 (LXX) and 31: 35-37 (MT) and the deviating selection of verbs in v. 37(35),12 are not recognisably linked to any variant or other textual element in their closer text context. They can therefore not be explained by any of the versions' purpose of reinterpreting or restructuring the immediate context.

Jeremiah 31:35-37 however is one of the intertexts alluded to by 33:1426. Its second part Jer 33:20-26 heavily leans on Jer 31:35-37 in its MT version. It can be shown, that those variants of Jer 31: 35-37 (MT) which are quoted in Jer 33:20-26 are highly relevant for the text's argument.

1 Jeremiah 33:14-26 Quoting 31:35-37 (MT): The Reorganisation of the Broader Context in the Masoretic Text

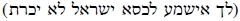

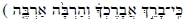

Jeremiah 33:20-26 heavily leans on 31:35-37. A number of textual elements in 33:20-26 are linked to textual elements in 31:35-37.13 The sequence of allusion follows the order of the MT.14

(i) 33:20 is an allusion to 31:35: God's ברית with day and night, which guarantees his ברית with David and with the Levites (33:20f.), reminds of the order of night and day in 31:35 (MT).

(ii) 33:24 is an allusion to 31:36: the refusal of Israel's recognition as a in front (לפניהס) of those questioning the covenant (33:23f.) corresponds to Israel's recognition as a in front of God (לפני) in 31:36.

(iii) 33:25 is an allusion to 31:36: according to 33:25 the ברית with day and night and the חוקות of heaven and earth15 guarantees that God will not abandon Jacob's and David's offspring. Heaven and earth as well as the abandonment of Jacob's (or Israel's) offspring link this last verse to 31:37.

The references of 33:20-26 to 31:35-37 (MT) follow the order of the MT. Jeremiah 33:22, which is linked to 31:37 (MT), breaks the symmetry of correspondence. Nevertheless it does clearly refer to 31:37 (MT). The counting of the host of heaven and the measuring (מדד) of the grains of the sands of the sea is a reminder of the measuring (מדד) of heaven and the exploration of the foundations of the earth in 31:37 (MT).16

2 Additional Intertexts in Jeremiah 33:14-26 and 31:35-37 (MT)

Some of the differences between the quoted MT version of 31:35-37 and its LXX counterpart correlate with details in other biblical intertexts, which are equally quoted by Jer 33:20-26.

Jeremiah 33:22 which is breaking the symmetry by its reference to 31:37, the quoted section's final verse, does not only refer to Jer 31:37. The counting (ספר) of the host of heaven and the measuring (מדד) of the sand of the sea and the announcement of a multitude of descendants (זרה) in 33:22 evoke the promise to Abraham according to Gen 15.17

Some of the keywords, which establish the link between Jer 33: 22 and Jer 31:37 (MT) also establish a link between Jer 33:22 and Gen 15:5. Jeremiah 33:22 decidedly refers to the MT version of Jer 31:37.While שמים occurs in the LXX (Jer 38:35) as well, the allusion of counting and measuring as well as the expression מדד only occurs in the MT (Jer 31:37).

3 Diachrony

Jeremiah 33:14-26 is usually classified as a supplement within its closer context.18 Jeremiah 33:14-26 is not only to a large extent made up of quotations from in and outside the book of Jeremiah; its absence in the LXX does not disturb the context's coherence. Though even as a supplement Jer 33:14-26 could have been later on consciously19 or unconsciously omitted by the LXX's Hebrew "Vorlage" or the LXX, a number of MT variants in the preceding passage Jer 33:1-13 which are interlinked with Jer 33:14-26 makes any conscious or unconscious omission of Jer 33:14-26 by the LXX less probable than a later addition by the MT. Jeremiah 33:1-13 could be less easily removed from the MT context than from the LXX.

The MT already mentions העיר הזה in 33:5 MT. The impression that העיר הזה in Jer 33:5 refers to the city of Jerusalem is at least underlined by Jerusalem's appearance in Jer 33:1.20 The MT's שם ששון in Jer 33:9, which does not have an equivalent in the LXX would miss a reference point, if Jerusalem's name would not be explicitly referred to in Jer 33:16.21 While העיר הזה in Jer 33:5 would still be understood without its backup in Jer 33:15, שם ששון in Jer 33:9 would be enigmatic. Any redaction omitting Jer 33:14-26 would also have to be held responsible for changing those details in Jer 33:1-13, which refer to Jer 33:14-26 of which at least שם ששון in Jer 33:9 without Jer 33:14-26 would then aim at an empty target.

Besides Jer 33:14-26 being well integrated into its MT context, the inter-dependency of Jer 31:35-37 (MT) and Jer 33:20-26 speaks against any erroneous omission of Jer 33:14-26 by the LXX and makes any deliberate omission improbable. While the change of verse order in 31:35-37 (MT) as well as the changing of verbs in v. 37 can be explained as being motivated by 33:14-26 (MT) creating a text base, which 33:14-26 (MT) - by linking this quoted passage to another quoted passage Gen 15:15 - could build on,22 the alternative is far less probable: why should the LXX have omitted 33:14-26 and afterwards destroyed the links between 31:35-37 and a no longer existing text?

E JEREMIAH 23:5-6

Jeremiah 23:5-6, which is equally quoted by Jer 33:14-26, might serve as a test case. Can differences between the versions of Jer 23:5-6 also be explained as being motivated by Jer 33:14 quoting it?

1 Jeremiah 23:5-6 in Both Versions

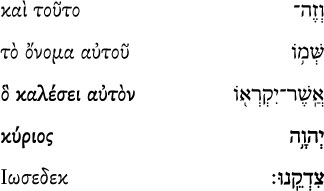

Jeremiah 23:5-6 closes a sequence of prophecies against the kings of Judah in 22:1-23:8.23 The short passage announces a descendant of David as a future ruler, who will bring justice to Israel and Judah. MT and LXX differ in a few details. In Jer 23:6 LXX the announced descendant of David is called by his prop- er name Ιωσεδεκ. Jeremiah 23:6 MT has a nominal phrase: יהוה צדקנו: Yhwh is our righteousness.

The most obvious change between the versions changes the sentence's grammatical structure without changing the order of words: if God is calling his [the branch's] name Ιωσεδεκ (LXX) or if his [the branch's] name is "God is our justice" depends on the grammatical function of יהוה/κύριος. In the LXX κύριος functions as subject to the preceding δ καλέσει αυτόν. In the MT it is subject to the subsequent predicative of the nominal phrase. The position of יהוה/κύριος in both sentences is the same.

The differing grammatical structure is closely connected to differing semantics. While the LXX has Ιωσεδεκ, which is a positive reference to a historic figure, the MT has צדקנו as predicative within the nominal phrase

24

24

2 Diachrony

Diachronic considerations are based on considerations about the difference between the name Ιωσεδεκ and צדקנו as part of the nominal phrase צדקנו יהוה in the respective contexts of the versions. The difference between the name Ιωσεδεκ and the phrase צדקנו יהוה has been discussed in terms of a relative chronology, as well as, considering the identity of Ιωσεδεκ as a historic figure, in terms of an absolute chronology of the Greek text.

Under the presumption of the rearrangement of the components of his name, (יה(וה and צדק, Ιωσεδεκ has been most frequently associated with Zedekiah.25 A similar case occurs in Jer 22:24 and 37:1, where כניהו, whose name seems to be rearranged in the same way, is clearly identified with יהוכין. That Ιωσεδεκ as a variant of the name צדקיה is not testified at any other place does not argue against this presumption, as כנהו only occurs in Jer 22:24, 27 and 37:1. If Ιωσεδεκ refers to Zedekiah, the LXX is likely not only to represent the older text, but also an old layer within the book of Jeremiah Zedekiah would not have been well qualified representing the future Davidic ruler after his violent death.26

Based on the appearance of Ιωσεδεκ in Ezra 3:2, 8 et al. within the LXX,27 where the Hebrew word is יוצדק van der Kooij associates Ιωσεδεκ with the high priest Joshua's father of the early Persian period.28 The possible understanding of the translators of the LXX or of the redactors of the MT of יוצדק -if יוצדק is to be considered part of what they read - must remain uncertain. It does not need to have been in harmony with the original authors' intentions. If and only if the LXX's translators (or - more likely - the redactors of the LXX's Hebrew pretext) had voluntarily changed the nominal phrase to the proper name, seems an intentional reference to the high priest's father an alternative worth considering. The LXX following the MT's word order speaks in favour of the LXX's closeness to its Hebrew "Vorlage," consequently for its precedence and against a voluntary misreading of the Hebrew text. 29

F JEREMIAH 33:15-16 AND 23:5-6

1 Jeremiah 33:15-16 Quoting 23:5-6

As Jer 33:20-26 builds on 31:35-37, 33:15-16 announcing the branch of righteousness quotes 23:5-6.30 33:15-16 quotes 23:5-6 according to the version of the MT. Unlike Jer 23:6 (LXX) and as 23:6 (MT) Jer 33:16 does not state the future ruler's proper name, but quotes the nominal phrase.

In relation to the quoted MT version of Jer 23:5-6 however 33:15-16 puts some accents differently. Differences between 33:15-16 and 23:5-6 MT are far more numerous and extensive than those between both versions of 23:5-6.

Jeremiah 33:15 misses מלך מלך in the description of the future ruler's activity, which would have been represented in both versions of Jer 23:5. While in the cited text Jer 23:5 (in both of its versions) the branch responsible for executing justice and righteousness is explicitly stated as doing so (that is: executing justice and righteousness) by ruling as a king, this is not the case in Jer 33:15 where מלך מלך has no equivalent - the branch responsible for executing justice and righteousness is not explicitly stated as doing so (that is, executing justice and righteousness) by ruling as a king.31 Ιωσεδεκ in 23:16 (LXX) and the nominal phrase יהוה צדקנו in 23:16 (MT) refer to a royal figure. Jerusalem replaces "Israel" as the counterpart of Judah in the first half of the v. 33:16a.32 The introductory phrase  and the city of Jerusalem being mentioned immediately before makes יהוה צדקנו in 33:16b refer not to any human ruler33 but to Jerusalem.34

and the city of Jerusalem being mentioned immediately before makes יהוה צדקנו in 33:16b refer not to any human ruler33 but to Jerusalem.34

2 Diachrony

Jeremiah 33:16 builds on 23:6 in the MT version. Groß assumes that יהוה צדקנו was already part of that version of Jer 23:6 which the authors of Jer 33:14-26 were referring to.35 According to Lust the MT replaces the individual king's proper name according to 23:6 LXX by the nominal phrase with regard to the name's reference to Jerusalem in Jer 33:16.36

Given the inexactness of the equivalent of יהוה צדקנו as referring to an individual figure or to the dynasty37 in 23:6 but to the city in 44:14, it cannot be stated with certainty whether the redactors of Jer 33:14-26 changed the proper name in 23:6 to יהוה צדקנו or whether they already read the nominal phrase.38 Any decision is further complicated by uncertainty concerning the dependency of the versions in Jer 23:6. If Ιωσεδεκ could be proven to represent the older version with some certainty, the probability of the attribution of the entry of the nominal phrases in Jer 23:6 MT to the authors of Jer 33:14-26 would increase.

G THE DIFFERENT MODES OF REWORKING THE TEXT IN THE MASORETIC TEXT

The redactors of the MT seem to be responsible for a greater number of variants than the LXX. While it seems unlikely that the LXX, mostly following a Hebrew word order even at the cost of awkward Greek,39 should be responsible for the intentional deletion or the reshaping of extended passages, the discussion of concrete examples has supported the impression, that it is the MT to which variants that interfere with their assumed "Vorlage" to a high degree can be ascribed to with a considerably higher probability. Some of these variants can even be shown to be interdependent.

Already Bogaert and Lust have shown that Jer 33:14-26 cites intertexts from within the book of Jeremiah in a shape that is likely to have been adjusted to the needs of the quoting text. Disregarding Bogaert and Lust however the degree of interference with those texts which are quoted, varies considerably. Not only are the differences between the versions of Jer 31(38):35-37 more profound than those between the versions of Jer 23:5-6. While Jer 33:20-26 stays close to the wording of 31:35-37 whenever alluding to it, the differences between Jer 33:15-16 and Jer 23:5-6 (MT) are more numerous than the differences between the versions of Jer 23:5-6.

It is obvious that not every detail of the quoted text is made to fit the redactors' interests. The redactors seem to have been far more reserved in editing Jer 23:5-6 than Jer 31:35-37. Their reservation towards Jer 23:5-6 is even more remarkable as it concerns a topic, which is on the one hand frequently referred to in Jer 33:14-26, the announcement of a Davidic ruler, but which is on the other hand depreciated within this newly created passage 33:14-26, wherever the redactors do not have to respect already existing text traditions and even when they are referring to them as is the case with Jer 23:5-6.

H THE DEVALUATION OF KINGSHIP

Several quoted texts refer to the theme of the Davidic ruler. Jeremiah 33:15-16 cites the announcement of a future Davidic ruler in Jer 23:5-6. 33:17-18, which promises descendants of David and the Levites, refers to the promise of descendants of David according to 2 Sam 7.40 Jeremiah 33:20-26 quoting Jer 31:35-37 without reference to a Davidic tradition uses the textual material to argue for the durability and stability of what is now (exceeding Jer 31:35-37) qualified as a covenant.

Texts from within the book of Jeremiah which Jer. 33:14-26 merely alludes to without literally citing them are hardly changed though some adjustment to the quoting text based on the model of the redactors' coping with Jer. 31:35-37 would have been better suited to their interests concerning the figure of David.

At the same time the importance of the Davidic figure is weakened by the redactors of the text committing themselves to a double strategy: the significance of the Davidic figure is devalued by its supplementation of a priestly figure. It is furthermore weakened, as differences between Jer 33:13-26 and those texts quoted concerning the Davidic theme often imply a deviation of the Davidic figure:

(i) While in the cited text 23:5, in both versions the branch responsible for executing justice and righteousness is explicitly said to execute justice and righteousness by ruling as a king

has no equivalent in 33:15.41

(ii) Ιωσεδεκ in 23:16 (LXX) and the nominal phrase

in 23:16 (MT) refer to a royal figure. Jeremiah 33:16 cites the nominal phrase. The introductory phrase

and the city of Jerusalem being mentioned immediately prior to it make it likely, that יהוה צדקנו refers not to any human ruler42 but to Jerusalem.43

(iii) The promise of countless descendants for Abraham (Gen 15), which is linked to both the descendants (זרה) of David and the descendants (זרה) of the Levites by Jer 33:22 better suits the descendants of the Levites. With regard to the descendants of David that image seems problematic. Only one descendant at a time would be able to occupy the throne.44

Those passages which do not duplicate, quote or allude to any other passage inside or outside of the book of Jeremiah enhance the trend of the devaluation of the Davidic figure: other than in 33:21, which quotes 1 Kgs 2:4 and parallels and has מלך, in Jer 33:26 the descendant of David is called a משל, not a מלך.

I FRAMES OF ORIENTATION

The redactors' of the versions differing worldviews and frames of orientation express themselves in their different modes of reworking their "Vorlage" as in what they change, add or erase. While interrogating the redactors' worldview and frame of orientation the versions of the text might reciprocally serve as their horizons of interpretation.

The LXX's word-for-word-correspondence to the MT even at the cost of awkward Greek wherever the versions are equivalent has been frequently noticed. The impression that the translators of the LXX seemed to have closely followed their Hebrew "Vorlage" is underlined by those examples discussed above: the majority of variants which can be assigned to the LXX with some probability are based on a change of grammatical structure which does not disturb the word for word correspondence or semantic shifts which might be understood as part of the translation process.45

For the translators of the LXX their "Vorlage" seems to have gained a far higher degree of text stability than for the redactors of the MT. At the same time the redactors of the LXX individualise their concept of what guarantees Israel's enduring character as an έθνος. According to the LXX Israel's existence as an έθνος according to God's standards is depending on those νόµοι, which are part of the covenant according to Jer 38:31-34 and are written on the people's heart.46 In opposition to those of the MT the LXX's supporting group seems not to have been decidedly interested in entities representing political power. In opposition to the MT, the LXX might be considered as rooted in some local or inner distance to the centre of power.

Jeremiah 33:14-26 (MT) links the stability of the cosmic order of Jer 31:35-37 to its concept of a covenant with David and the Levites guaranteeing Israel's stability as a nation.47 In opposition to the LXX which individualises the preconditions of Israel's continuous existence as an έθνος, the MT introduces a covenant which establishes Israel as a political entity. The covenant, which Jer 33:14-26 introduces by its supplement referring to Jer 31:35-37, has already been part of the immediate preceding passage Jer 31:31-34.

The concept of Jer 33:14-26 of Israel as a political entity has been frequently used in an effort to date the MT. Jeremiah 33:14-26 has been read as considering pretty much every imaginable period of time, starting with Jeremiah himself and ending with the Maccabees.48

The seeming double leadership of a royal and a priestly figur4e9 is usuall5y0 taken as an argument for either the early Persian period (Gôldmann,49 Pietsch,50 Lust,51 Bogaert) or the period of the Maccabees (Duhm, Bogaert in one arti-cle,52 Schenker53 and Piovanelli54) where the royal and the priestly function are united in the person of the Maccabean leader. It should however not be overlooked that the few parallels insinuating a double leadership of a royal and a priestly figure (cf. the series of prophetic visions in Zechariah) imagine the priestly counterpart of the royal figure as an individual. Those parallels which mention a covenant with a priestly figure usually refer to an individual. Sir 45:23-26 which has a διαθήκη ειρήνης ("covenant of peace") with Phinehas and his descendants, which is even parallel with a διαθήκη with David,55 obviously refers to the high priest.56 Other than that, Jer 33:14-26 does not refer to the office of the high priest and seems independent of a tradition that makes Phinehas the ancestor of the Maccabees.

While Jer 33:14-26 refers to a priestly group rather than to an individual, the text's analysis has furthermore shown that the royal and the priestly protagonists do not have the same relevance to the redactors and authors of Jer 33:1426. From the point of view of the redactors the stability of the traditional text varies depending on texts and topics. Texts considering a Davidic leader already seem to have gained a certain degree of text stability. Considering that text stability and the importance of traditions concerning the Davidic figure for the line of argument of Jer 33:14-26 (and consequently for the version's sup- porting group), the simultaneous devaluation of that royal Davidic figure in every text newly created by the MT's redactors seems even more significant. The importance and high stability of texts concerning the royal figure of David and its simultaneous devaluation in favour of the priesthood speaks in favour of a period sometime after a royal figure ceased to exist. The earliest period possible would be the early Persian period.

Building on the memory of the Davidic kingdom and a collective Leviti-cal priesthood the MT's supporting group seems closely connected to the centre of power in Jerusalem. It is extremely interested in Israel as a durable political entity. This interest points to a time in which Israel's position as a durable political entity seems not to have been self-evident. The high evaluation of the priesthood, not of the high priest or any individual priestly figure, either speaks in favour of a period in which such an individual priestly leading figure did not exist or in favour of a group which did not favour it. As such a figure - in contrast to the Davidic king - is not even mentioned as a positive or negative horizon, the text is likely to be earlier than any historic high priest. A situation in which such a reference would have been deliberately avoided, perhaps because it would not have been advisable, cannot however be explicitly excluded.

A fairly close parallel to Jer 33:14-26 is offered by Isa 55:3.57 Isaiah 55:3 links the "mercies of David"  to the ברית with the text's addressees. If those addressees, as the servant's followers, have a Levitic background,58 this text is relatively the closest parallel to Jer 33:14-26. Jeremiah 33:14-26 differs from Isa 55:3 in its apparent interest in Israel as a political entity and Jerusalem as the centre of political power. Being interested in Israel as a political entity as well as in its representatives on the one hand and referring to a priestly collective in this function on the other, Jer 33:14-26 seems unique. Jeremiah 33:14-26 gives testimony of a supporting group, whose idea of Israel being part of its frame of orientation competes with other concepts of Israel. Those competing ideas include different concepts of Israel as a political entity as well as concepts which in confrontation with these shrink back from defining Israel as a political entity at all. The latter is represented by groups whose frames of orientation appear as a negative horizon within Jer 33:14-26 itself (cf. v. 24). They are in a different way represented by the LXX's idea of what guarantees Israel's enduring character as an έ'θνος.

to the ברית with the text's addressees. If those addressees, as the servant's followers, have a Levitic background,58 this text is relatively the closest parallel to Jer 33:14-26. Jeremiah 33:14-26 differs from Isa 55:3 in its apparent interest in Israel as a political entity and Jerusalem as the centre of political power. Being interested in Israel as a political entity as well as in its representatives on the one hand and referring to a priestly collective in this function on the other, Jer 33:14-26 seems unique. Jeremiah 33:14-26 gives testimony of a supporting group, whose idea of Israel being part of its frame of orientation competes with other concepts of Israel. Those competing ideas include different concepts of Israel as a political entity as well as concepts which in confrontation with these shrink back from defining Israel as a political entity at all. The latter is represented by groups whose frames of orientation appear as a negative horizon within Jer 33:14-26 itself (cf. v. 24). They are in a different way represented by the LXX's idea of what guarantees Israel's enduring character as an έ'θνος.

To be more precise other sequences which are marked by a high degree of interactivity need to be taken into account.59

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Berges, Ulrich. "Neuer Anfang und neuer Davidbund in Tritojesaja." Pages 391-406 in Ex oriente Lux: Studien zur Theologie des Alten Testamentes, FS R. Lux. Edited by Angela Berlejung and Raik Heckl. Arbeiten Zur Bibel Und Ihrer Geschichte 39. Leipzig: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, 2012. [ Links ]

Bogaert, Pierre-Maurice. "Urtext, texte court et relecture: Jérémie XXXIII 14-26 TM et ses preparations." Pages 237-247 in Congress volume, Leuven, 1989. Edited by John A. Emerton. Supplements to Vetus Testamentum 43. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1991. [ Links ]

______. "Jérémie 17,1-4 TM, oracle contre ou sur Juda propre au texte long: Annoncé en 11,7-8.13 et en 15,12-14 TM." Pages 59-74 in La double transmission du texte biblique: Études d'histoire du texte offertes en hommage à Adrian Schenker. Edited by Yohanan Goldman. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: 2001. [ Links ]

Bohnsack, Ralf, Winfried Marotzki and Michael Meuser, eds. Hauptbegriffe qualitative Sozialforschung: Ein Wörterbuch. Opladen: Leske + Budrich, 2003. [ Links ]

Bohnsack, Ralf. Rekonstruktive Sozialforschung: Einführung in qualitative Methoden. Opladen: Leske + Budrich, 2003. [ Links ]

Fischer, Georg. Jeremia 1-25. Herders theologischer Kommentar zum Alten Testament. Freiburg i.Br.: Herder, 2005. [ Links ]

______."Die Diskussion um den Jeremiatext." Pages 612-629 in Die Septuaginta: Texte, Kontexte, Lebenswelten: Internationale Fachtagung veranstaltet von Septuaginta Deutsch (LXX.D), Wuppertal 20.-23. Juli 2006. Edited by Martin Karrer, Wolfgang Kraus and Martin Meiser. WUNT 219. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2007. [ Links ]

______. Jeremia: Der Stand der theologischen Diskussion. Darmstadt: WBG, 2007. [ Links ]

Gôldman, Yôhãnan. Prophétie et royauté au retour de l'exil: Les origines littéraires de la forme massorétique du livre de Jérémie. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 118. Fribourg: Universität-Verlag, 1992. [ Links ]

Groß, Walter. "Israels Hoffnung auf die Erneuerung des Staates." Pages 65-96 in Studien zur Priesterschrift und zu alttestamentlichen Gottesbildern. Edited by Walter Gross. Stuttgart: Verlag Katholisches Bibelwerk, 1999. [ Links ]

Holladay, William L. Chapters 26-52. Vol. 2 of Jeremiah: A Commentary on the Book of the Prophet Jeremiah. Hermeneia: A Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1989. [ Links ]

Karrer-Grube, Christiane. "Von der Rezeption zur Redaktion: Eine intertextuelle Analyse von Jeremia 33,14-26." Pages 105-121 in Sprachen-Bilder-Klänge. Edited by Christiane Karrer-Grube, Jutta Krispenz and Thomas Krüger; Münster: Ugarit-Verlag 2009. [ Links ]

Loos, Peter and Burkhard Schäffer. Das Gruppendiskussionsverfahren: Theoretische Grundlagen und empirische Anwendung. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2011. [ Links ]

Lust, Johan. "The Diverse Text Forms of Jeremiah and History Writing with Jer 33 as a Test Case." Journal of Northwest Semitic Languages 20/1 (1994): 31-48. [ Links ]

______. "Messianism and the Greek Version of Jeremiah: Jer 23,5-6 and 33,14-26." Pages 41-67 in Messianism and the Septuagint: Collected essays. Edited by Jo-han Lust and Katrin Hauspie. Bibliotheca Ephemeridum theologicarum Lovaniensium 178. Leuven: University Press, 2004. [ Links ]

Macchi, Jean-Daniel. "Les doublets dans le livre de Jérémie." Pages 119-150 in The Book of Jeremiah and its Reception: Le livre de Jérémie et sa réception. Edited by Adrian H. Curtis and Thomas Römer, Leuven: University Press 1997. [ Links ]

Mannheim, Karl. Strukturen des Denkens. Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp, 2003. [ Links ]

McKane, William. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on Jeremiah. Volume 1. Edinburgh: Clark, 1986. [ Links ]

Pietsch, Michael. "Dieser ist der Spross Davids": Studien zur Rezeptionsgeschichte der Nathanverheissung im alttestamentlichen, zwischentestamentlichen und neutestamentlichen Schrifttum. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener, 2003. [ Links ]

Piovanelli, Pierluigi. "JRB 33,14-26 ou la continuité des institutions à l'époque maccabéene." Pages 255-276 in The Book of Jeremiah and its Reception: Le livre de Jérémie et sa réception. Edited by Adrian H. Curtis and Thomas Römer. Leuven: University Press, 1997. [ Links ]

Schenker, Adrian. "La rédaction longue du livre de Jérémie doit-elle être datée au temps des premiers Hamonéens?" Ephemerides theologicae lovanienses 70 (1994): 281-293. [ Links ]

Stipp, Hermann-Josef. Deuterojeremianische Konkordanz. St. Ottilien: EOS-Verlag, 1998. [ Links ]

______. Das masoretische und alexandrinische Sondergut des Jeremiabuches: Textgeschichtlicher Rang, Eigenarten, Triebkräfte. Freiburg, Schweiz: Universität-Verlag, 1994. [ Links ]

Tino, Jozef, King and Temple in Chronicles: A Contextual Approach to their Relations. Forschungen zur Religion und Literatur des Alten und Neuen Testaments 234. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2010. [ Links ]

Tov, Emanuel. "The Jeremiah Scrolls from Qumran," Römische Quartalschrift für christliche Altertumskunde und Kirchengeschichte 54 (1989): 189-206. [ Links ]

Van der Kooij, Arie. "Zum Verhältnis von Textkritik und Literarkritik: Überlegungen anhand einiger Beispiele." Vetus Testamentum 66 (1997): 185-202. [ Links ]

Vonach, Andreas. "Die Jer-LXX als Dokument des alexandrinischen Judentums." Habilitation, University of Innsbruck, 2005. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Dr. Johanna Erzberger

Institut Catolique de Paris (Catholic University of Paris)

21, rue d'Assas, 75270 Paris Cedex 06 FRANCE

Research associat

Department of Old Testament Studies

Faculty of Theology, University of Pretoria

Email: johannaerzberger@web.de

1 The author is a research associate of the Department of Old Testament Studies at the University of Pretoria.

2 If 4QJerb and 4QJerd represent the LXX, Qumran gives evidence that those versions were used at the same time. Cf. Emanuel Tov, "The Jeremiah Scrolls from Qumran," RQ 54 (1989): 191. If 4QJerb and 4QJerd cannot to be proven to be this close to the LXX, as some scholars argue (cf. Andreas Vonach, "Die Jer-LXX als Dokument des alexandrinischen Judentums" [Habilitationsgeschrifte, University of Innsbruck, 2005], 40 [cf. also pp. 207-215, "Jer 10,1-10: Crux interpretum für die kürzere LXX-Version?"]; Georg Fischer, Jeremia: Der Stand der theologischen Diskussion [Darmstadt: WBG, 2007], 20-22), there is still evidence that different versions of Jeremiah were used in Qumran.

3 Stipp and Fischer mark two antagonistic positions. Stipp assumes that the majority of the variants of the proto-MT, a great number of which consist of stereotyped material and make use of other parts of the book, serve unifying tendencies. According to Stipp this material due to its nature is unsuitable for further content analysis. Cf. Hermann-Josef Stipp, Deuterojeremianische Konkordanz (St. Ottilien: EOS-Verlag, 1998), 2. More extended supplements, among them Jer 33:14-26, are inhomogeneous and thematically incongruent. Cf. Hermann-Josef Stipp, Das masoretische und alexandrinische Sondergut des Jeremiabuches: Textgeschichtlicher Rang, Eigenarten, Triebkräfte (Freiburg, Schweiz: Universität-Verlag, 1994), 137138. Fischer considers the MT the Greek translation's pretext because of the LXX's coherency, which witnesses the LXX's straightening of the text. Cf. Georg Fischer, Jeremia 1-25 (HTKAT; Freiburg i.Br.: Herder, 2005), 37-120 (39-42); Georg Fischer, "Die Diskussion um den Jeremiatext," in Die Septuaginta: Texte, Kontexte, Lebenswelten. Internationale Fachtagung veranstaltet von Septuaginta Deutsch (LXX.D), Wuppertal 20.-23. Juli 2006 (ed. Martin Karrer, Wolfgang Kraus and Martin Meiser; WUNT 219; Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2007); Georg Fischer, Jeremia: Der Stand. Exegetes, who consider the MT's pretext close to a Hebrew equivalent of the LXX, admit that one could hardly argue for a Hebrew equivalent of the LXX as a preliminary stage of the MT by means of historic critical methods. Cf. William McKane, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on Jeremiah (vol. 1; Edinburgh: Clark, 1986), 1084.

4 Cf. Karl Mannheim, Strukturen des Denkens (Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp, 2003).

5 Cf. Peter Loos and Burkhard Schäffer, Das Gruppendiskussionsverfahren: Theoretische Grundlagen und empirische Anwendung (Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2011), 61. Ralf Bohnsack, Winfried Marotzk and Michael Meuser eds., Hauptbegriffe qualitative Sozialforschung: Ein Wörterbuch (Opladen: Leske + Budrich, 2003), 67. Ralf Bohnsack, Rekonstruktive Sozialforschung: Einführung in qualitative Methoden (Opladen: Leske + Budrich, 2003), 137. Bohnsack developed his methods while working on group discussions. Bohnsack's methods seem especially helpful for the analysis of texts with a long history of formation, whose redactors are working with an already existing text. As this text is of relevance for a religious community, to which its redactors belong, it might be more appropriate and effective to ask for the groups which are supporting and reworking these texts. Cf. Bohnsack, Rekonstruktive Sozialforschung.

6 A possible relation to Jer 29:14 is less obvious and has frequently been doubted for good reasons. It would be worthwhile to have a separate discussion which will not be considered in this article. Cf. Stipp, Das masoretische, 136. Stipp argues with different contents of those  and the missing of the motif of return from exile in Jer 33:14-26. Cf. Michael Pietsch, "Dieser ist der Spross Davids": Studien zur Rezeptionsgeschichte der Nathanverheissung im alttestamentlichen, zwischentestamentlichen und neutestamentlichen Schrifttum (Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener, 2003), 75-93 who follows Stipp's argumentation.

and the missing of the motif of return from exile in Jer 33:14-26. Cf. Michael Pietsch, "Dieser ist der Spross Davids": Studien zur Rezeptionsgeschichte der Nathanverheissung im alttestamentlichen, zwischentestamentlichen und neutestamentlichen Schrifttum (Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener, 2003), 75-93 who follows Stipp's argumentation.

7 Cf. Pierre-Maurice Bogaert, "Urtext, texte court et relecture: Jérémie XXXIII 1426 TM et ses preparations," in Congress volume, Leuven, 1989 (ed. John A. Emerton; VTSup 43; Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1991), 237-247; Johan Lust, "The Diverse Text Forms of Jeremiah and History Writing with Jer 33 as a Test Case," JNSL 20/1 (1994): 3148; Johan Lust, "Messianism and the Greek Version of Jeremiah: Jer 23,5-6 and 33,14-26" in Messianism and the Septuagint: Collected essays (ed. Johan Lust and Katrin Hauspie; BETL 178; Leuven: University Press, 2004), 45; Jean-Daniel Macchi, "Les doublets dans le livre de Jérémie," in The Book of Jeremiah and its Reception: Le livre de Jérémie et sa réception (ed. Adrian H. Curtis and Thomas Römer; Leuven: University Press, 1997), 145.

8 If the supporting groups values and orientation are characterised both by their mode of reworking the text and by the propositions they make, chronologies have principally to be taken into account. Interdependencies help to argue in favour of chronologies. Uncertainties remain.

9 Cf. Pietsch, "Dieser ist der Spross Davids," 92.

10 Cf. Bogaert, "Urtext," 243.

11 Cf. Bogaert, "Urtext," 245.

12 TTO, nip'al (MT) versus ύψόω (LXX) and חקר, nip'al (MT) versus ταπεινόω (LXX).

13 Cf. Bogaert, "Urtext," 241-247.

14 Cf. Bogaert, "Urtext," 242.

15 William Lee Holladay, Chapters 26-52 (vol. 2 of Jeremiah: A Commentary on the Book of the Prophet Jeremiah; Hermeneia; Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1989), 227228, reads בריתי as a misreading for בראתי, but the parallel in Jer 33:20 also has בריתי.

16 Cf. Bogaert, "Urtext," 246.

17 Another possible intertext would have been Gen 22:17

, which also has שמים and חול היס. The context of Gen 22 though does not explicitly refer to a covenant. In the context of Jer 23:5f, one of the texts cited in Jer 33:14-26, there is an allusion to God's promise to Abraham in 23:3. Cf. Walter Groß, "Israels Hoffnung auf die Erneuerung des Staates," in Studien zur Priesterschrift und zu alttestamentlichen Gottesbildern (ed. Walter Gross; Stuttgart: Verlag Katholisches Bibelwerk, 1999), 82, who associates 23:3 with 33:22. In contrast to 33:22 in 23:3 the promise of multiplication refers to the people in general, not to the זרה of David and the Levites.

, which also has שמים and חול היס. The context of Gen 22 though does not explicitly refer to a covenant. In the context of Jer 23:5f, one of the texts cited in Jer 33:14-26, there is an allusion to God's promise to Abraham in 23:3. Cf. Walter Groß, "Israels Hoffnung auf die Erneuerung des Staates," in Studien zur Priesterschrift und zu alttestamentlichen Gottesbildern (ed. Walter Gross; Stuttgart: Verlag Katholisches Bibelwerk, 1999), 82, who associates 23:3 with 33:22. In contrast to 33:22 in 23:3 the promise of multiplication refers to the people in general, not to the זרה of David and the Levites.

18 Cf. Bogaert, "Urtext," 238; Lust, "Diverse Text," 37; Lust, "Messianism," 54; Jozef Tiňo, King and Temple in Chronicles: A Contextual Approach to their Relations (FRLANT 234; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2010), 128.

19 Cf. Arie van der Kooij, "Zum Verhältnis von Textkritik und Literarkritik: Überlegungen anhand einiger Beispiele," VT 66 (1997): 197.

20 Cf. Lust, "Diverse Text," 37.

21 Cf. Lust, "Messianism," 54.

22 Cf. Bogaert, "Urtext," 242; Lust, "Diverse Text," 42; Lust, "Messianism," 61; Yôhānan Gôldman, Prophétie et royauté au retour de l'exil: Les origines littéraires de la forme massorétique du livre de Jérémie (OBO 118; Fribourg: Universität-Verlag, 1992), 42; Pierluigi Piovanelli, "JRB 33,14-26 ou la continuité des institutions à l'époque maccabéene," in The Book of Jeremiah and its Reception: Le livre de Jérémie et sa réception (ed. Adrian H. Curtis and Thomas Römer, Leuven: University Press, 1997), 268.

23 In the MT two verses follow (23:7-8) that oppose the Exodus from Egypt with the return from exile. In the LXX these verses close the sequence of prophecies against the prophets.

24 The Masora uses a pāsēq to indicate a break between יהוה and following the LXX's structure of the sentence, reading, "The Lord will call him: our righteousness." Because the Masora is more recent than the versions, the unvocalised (proto-) MT and the LXX, it does not serve the debate and can be neglected in this article.

25 Cf. Lust, "Diverse Text," 38; Lust, "Messianism," 43.

26 For this reason Van der Kooij is opposed to this solution. Cf. Van der Kooij, "Zum Verhältnis," 195.

27 Ezra 3:2, 8; 5:2; 10:18; Neh 12:26; Sir 49:12; Hag 1:1, 12, 14; 2:2, 4; Zech 6:11.

28 Cf. Van der Kooij, "Zum Verhältnis," 197.

29 The LXX must have read either

30 Cf. Lust, "Diverse Text," 37.

31 Cf. Lust, “Diverse Text,” 38.

32 Cf. Lust, "Diverse Text," 38.

33 Cf. Lust, "Diverse Text," 40; Christiane Karrer-Grube, "Von der Rezeption zur Redaktion: Eine intertextuelle Analyse von Jeremia 33,14-26," in Sprachen-Bilder-Klänge (ed. Christiane Karrer-Grube, Jutta Krispenz and Thomas Krüger; Münster: Ugarit-Verlag 2009), 109.

34 Cf. Groß, "Israels Hoffnung," 84. In the wider context of 33:15-26 in 33:5 the mention of Jerusalem is a surplus of the MT. Jeremiah 33:9 MT refers to the city's name. Cf. Bogaert, "Urtext," 239; Lust, "Diverse Text," 37; Lust, "Messianism," 45.

35 Cf. Groß, "Israels Hoffnung," 84.

36 Cf. Lust, "Messianism," 45, 51.

37 Cf. Lust, "Diverse Text," 39.

38 Cf. Lust, "Messianism," 45.

39 Misreading, alternative vocalisations, involuntary deletions or variants in the Hebrew pretext have to be taken into account.

40 Cf. Pietsch, "Dieser ist der Spross Davids," 92.

41 Cf. Lust, "Messianism," 56.

42 Cf. Lust, "Diverse Text," 40; Karrer-Grube, "Von der Rezeption," 109. Groß sees a shift from a single figure in Jer 23 to the Davidic Dynasty in Jer 33. Cf. Groß, "Israels Hoffnung," 84. According to Lust the attention shifts from an individual king in 23:6 LXX to a dynasty in 23:6 MT to the city in 33:16. Cf. Lust, "Diverse Text," 39. A few years later Lust already sees 23:6 MT, modeled after 33:16, as referring to Jerusalem. Cf. Lust, "Messianism," 45, 51.

43 In the wider context of 33:15-26 in 33:5, the mention of Jerusalem is a surplus of the MT. Jeremiah 33:9 MT refers to the city's name. Cf. Bogaert, "Urtext," 239; Lust, "Diverse Text," 37; Lust, "Messianism," 45.

44 Cf. Lust, "Diverse Text," 43.

45 Maintaining the word for word correspondence of the Greek and the known Hebrew of the MT differences in Jer 23:5-6 which affect the content of these verses are the mere result of a change of grammatical structure. The equivalence of νόµοι in Jer 38:37 in the LXX and חוקים in the corresponding verse Jer 31:36 in the MT is an example of a word-for-word-correspondence, which is accompanied by a semantic shift. While νόµοι in Jer 38:37 creates a reference with Jer 38:31, such a reference is not recognisable within the Hebrew text. The translation of different Hebrew words by the same Greek word or one Hebrew word by different Greek words allows the production of varying references. The only further going interference is the possible deletion of חקה in v. 35.

46 It is the λαός (31:33), equivalent to העם, that is emphasised. Cf. Karrer-Grube, "Von der Rezeption," 108.

47 According to Bogaert Jer 33:14-26 (MT) links the covenant according to Jer 31:3133 and the cosmic order according to Jer 31:35-37. Cf. Bogaert, "Urtext," 241. Cf. also Lust, "Diverse Text," 43; Lust, "Messianism," 61.

48 Cf. Pietsch, "Dieser ist der Spross Davids," 78; Piovanelli, "JRB 33,14-26," 260.

49 Cf. Gôldman, Prophétie et royauté, 225-226; cf. Adrian Schenker, "La rédaction longue du livre de Jérémie doit-elle être datée au temps des premiers Hamonéens?" ETL 70 (1994): 281-282.

50 Cf. Pietsch, "Dieser ist der Spross Davids," 86.

51 Cf. Lust, "Diverse Text," 42; Lust, "Messianism,"; Schenker "La rédaction," 281282.

52 Cf. Pierre-Maurice Bogaert, "Jérémie 17,1-4 TM, oracle contre ou sur Juda propre au texte long: Annoncé en 11,7-8.13 et en 15,12-14 TM," in La double transmission du texte biblique: Études d'histoire du texte offertes en hommage à Adrian Schenker (ed. Yohanan Goldman; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: 2001), 73-74.

53 Cf. Schenker, "La rédaction," who with regard to the preservation of the Davidic theme considers the authors among the followers of the Maccabean at the beginning of their revolt rather than of the Hasmonean dynasty.

54 Cf. Piovanelli, "JRB 33,14-26," 273.

55 Lust, "Diverse Text," 41 strongly stresses this parallel.

56 Numbers 18:19 has a "covenant of salt" with Aaron, Num 25:13 and Sir 45:23-26 with Phinehas and his descendants. Only 2 Sam 23:5 and 2 Chr 13:5 ("covenant of salt") have a ברית between God and David.

57 The only other example for a ברית between God and the collective of the Levites is Neh 13:29, according to which this ברית has been violated.

58 Cf. Ulrich Berges, "Neuer Anfang und neuer Davidbund in Tritojesaja," in Ex oriente Lux: Studien zur Theologie des Alten Testamentes, FS R. Lux (ed. Angelika Berlejung and Raik Heckl; ABG 39; Leipzig: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, 2012), 391-406.

59 The question of priesthood and political power interests the MT also at other places cf. Jer 30:30-31:1.