Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Old Testament Essays

versão On-line ISSN 2312-3621

versão impressa ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.26 no.2 Pretoria Jan. 2013

Thematic correspondences between the Zedekiah texts of Jeremiah (Jer 21-24; 37-38)1

Wendy L. Widder

Logos Bible Software

ABSTRACT

This article argues that the Jeremiah-Zedekiah encounters of Jer 37-38 correspond thematically to the Zedekiah Cycle of chs. 21-24 in at least two important ways. First, the later chapters provide a narrative enactment of the judgment on Judah 's institutions that the Zedekiah Cycle foretold, namely, judgment on Zedekiah himself and the entire Judahite kingship. Secondly, in the character of Ebed-Melech, the chapters include a narrative prefiguring of the "righteous branch" foretold in 23:5-6. To demonstrate these correspondences, the article first examines the narrative structure of the Jeremiah-Zedekiah encounters of chs. 37-38 and determines that the focus of the narrative is the unjust imprisonment and suffering of Jeremiah. The article then explores how this narrative structure provides a backdrop for understanding both Zedekiah and Ebed-Melech, especially in light of the earlier prophecies of the Zedekiah Cycle.

A INTRODUCTION

The book of Jeremiah includes two blocks of text that feature Zedekiah: the Zedekiah Cycle of chapters 21-24 and the Jeremiah-Zedekiah encounters of chapters 37-38. While others have analyzed these respective blocks of Zedekiah texts2 and probed the redactional development of Zedekiah as a character,3 an adequate development of the thematic correspondence between the two blocks of text has not yet been done.

In this essay I argue that the Jeremiah-Zedekiah encounters of chapters 37-38 correspond thematically to the earlier Zedekiah Cycle of chapters 21-24 in at least two important ways. First, the later chapters provide a narrative enactment of the failure of Judah's leadership described in chapters 21-24 and leads into the account of their judgment that the Zedekiah Cycle foretold. Secondly, in the character of Ebed-Melech, the chapters include a narrative prefiguring of the "righteous branch" foretold in Jer 23:5-6 of the Zedekiah Cycle. To demonstrate these correspondences, I will first overview the structure and emphases of the Zedekiah Cycle of chapters 21-24. Then I will examine the narrative structure of the Jeremiah-Zedekiah encounters of chapters 37-38 and demonstrate that the focus of the narrative is the unjust imprisonment and suffering of Jeremiah. Finally, I will explore how this narrative structure provides a backdrop for understanding both Ebed-Melech and Zedekiah, especially in light of the earlier prophecies of the Zedekiah Cycle.

B THE ZEDEKIAH CYCLE: JEREMIAH 21-24

Stulman calls the text of Jer 21-24 the fifth and final "macro-structural unit" in the first scroll of Jeremiah.4 The cycle of narratives and oracles includes a series of condemnations against "the royal Davidic dynasty and other upper-tiered positions in the sociopolitical hierarchy" of sixth-century Judah.5

Zedekiah is significant in name and deed for understanding the full impact of this block of text. Prophecies directed against King "YHWH-Is-My-Righteousness" frame the series of oracles, and Yhwh's promise to raise up a righteous branch, a king named "YHWH is our righteousness," lies at the heart of the textual block (23:5-6). The arrangement of the components, detailed below, draws attention to this great promise of a king who will reign wisely and execute justice and righteousness.

- Oracle against Zedekiah (21:1-10). God rejects Zedekiah's request for deliverance and says he will hand over Zedekiah and the entire city to Nebuchadnezzar.

- Oracles against the institution of the Davidic king, the "house of the king of Judah" (21:11-22:30). This set of oracles "accentuates the conditional nature of the Davidic dynasty as well as its utter failure" to meet God's standards for justice and righteousness.6 Judgment is imminent.

- Oracle against the institution of shepherds (leaders) of Israel and the subsequent promises to . . .

- raise up new ones who will actually care for the people;

- raise up a righteous branch, a wise king who executes justice and righteousness;

- carry out a new exodus for his scattered people (23:1-8).

- Oracles against the institution of prophetism (23:9-40). God indicts the lying prophets who have proclaimed their own message, "delusions of their own minds" (23:26 niv), and disregarded the word of Yhwh.

- Oracle against Zedekiah (24:1-10). In the vision of the fig baskets, God says he will banish and destroy Zedekiah, his officials, and the survivors in Jerusalem.

The Zedekiah Cycle of chapters 21-24 declares the bankruptcy of and impending judgment on Judah's institutions: the Davidic kingship, the leaders, and the prophets. Zedekiah himself makes a mockery of his own name. At the heart of this textual block, Yhwh proclaims the one who will embody the meaning of Zedekiah's name; he will be the righteous alternative to the failed and doomed Davidic kings, national leaders, and false prophets.

C JEREMIAH 37-38: THE NARRATIVE STRUCTURE

The narrative of Jer 37-38 contains two accounts of people trying to destroy Jeremiah. First, in chapter 37 (vv. 11-16) the king's officials arrest, beat, and imprison the prophet in the house of Jonathan the scribe when Jeremiah tries to leave Jerusalem (37:12). Jeremiah's plea to Zedekiah later in the chapter that he not be sent back to Jonathan's house lest he die there indicates the severity of his ordeal and the clear intent of the officials. A second group of officials report Jeremiah's treasonous words to Zedekiah in chapter 38 (vv. 1-3) and demand his death. The king washes his hands of the prophet, and the officials throw him into a cistern to die.

1 Traditional Ways of Organizing

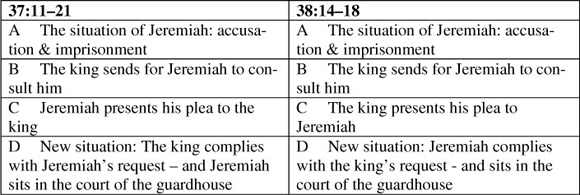

Noting the similarity of events and sequence between the two accounts of Jeremiah's imprisonments, commentators have traditionally organized the chapters as parallel stories of either Jeremiah's imprisonments or of his encounters with the king.7 Holt's chart provides an example of such an organization:8

There are at least two difficulties with organizing the narrative according to a perceived parallel structure. First, such an arrangement does not adequately account for the role of the first ten verses of chapter 37. Jeremiah's confrontations with king's officials do not begin until v. 11, and Zedekiah and Jeremiah do not have their first encounter until 37:17. Thus, 37:1-10 do not relate directly to either the prophet-king encounters or to Jeremiah's imprisonments. What then is the narrative function of vv. 1-10 in the larger narrative structure of parallel accounts?

A second difficulty involves the relationship of chapter 36 to chapters 37-38. The accounts of Jeremiah's imprisonments immediately follow the account of Jehoiakim's scroll burning in 36, so on the one hand, they complete the narrator's portrayal of a people, specifically a king, who not only refuse to hear Yhwh's word but also go to great lengths to destroy it: the written word in 36 and the messenger of the word in chapters 37-38. On the other hand, one might wonder why the narrator needed back-to-back accounts of Jeremiah's imprisonments to make this point. Could not one have served the purpose of providing a complementary account to 36?9

2 A Better Way, Based on Repetition

A reading of the narrative that allows the repetition in the text, rather than the surface similarity of events, to dictate the structure can better explain the narrative significance of the first ten verses and the use of back-to-back accounts with so many similarities. In his list of "motivating or interpretive rules" for biblical repetition, Sternberg includes compositional framework, a category that applies to the use of repetition in Jer 37-38.10 By using repetition to organize the scenes of these chapters, the narrator can further develop a theme already begun in the first cycle of Zedekiah texts earlier in the book.

Notice the repetition of exact phrasing as well as the repetition of a related idea:

- 37:16, "Jeremiah was put into...a dungeon, where he remained many days."

- 37:21, "So Jeremiah remained in the courtyard of the guard."

- 38:6, "And Jeremiah sank down into the mud."

- 38:13, "And Jeremiah remained in the courtyard of the guard."

- 38:28, "And Jeremiah remained in the courtyard of the guard."11

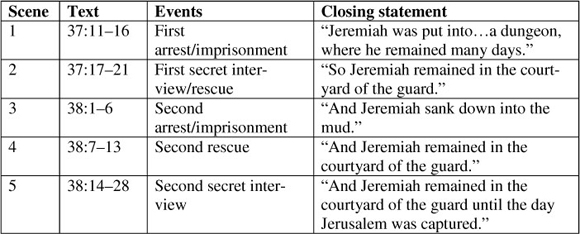

These five statements about the imprisonments of Jeremiah both focus the reader's attention on the overriding theme of the narrative block - namely, Jeremiah's unjust captivity - and form the hinges between five scenes that begin in 37:11:

If, as proposed here, the first scene begins in vs. 11 ![]()

![]() , how do the first ten verses of chapter 37 set up the overall narrative?

, how do the first ten verses of chapter 37 set up the overall narrative?

2a The Introductory Section

The introductory section of 37:1-10 accomplishes three things: (1) it provides a hermeneutical key for the rest of the narrative; (2) it hints at the theme of confinement that dominates the narrative; (3) it introduces two conflicting versions of reality that faced Jerusalem and, more importantly, Zedekiah.

- The hermeneutical key. The opening verse (37:1) identifies a herme-neutical key for the next two chapters: namely, nobody listens to (שמע) Yhwh's words through Jeremiah. Neither the king nor his attendants nor the people of the land. At times in the narrative to follow, the reader may be tempted to sympathize with Zedekiah and feel that his hands were politically tied, but the narrator has no such sympathy. Zedekiah's problem was not political or personal. It was spiritual. He would not listen to the words of Yhwh.12

- The theme of imprisonment. The imprisonment of Jeremiah will emerge as a dominant theme when the text begins its drumbeat about his captivity in v. 16, but vv. 4-5 link Jeremiah's then freedom and impending imprisonment to the freedom and captivity of Jerusalem. By including here the otherwise irrelevant and redundant statement that Jeremiah was "free because he had not yet been imprisoned" with the statement about affairs in Jerusalem at the time (namely, the Babylonians had withdrawn because of the Egyptian presence), the narrator casts the theme of freedom and imprisonment beyond Jeremiah's circumstances. Both Jeremiah and Jerusalem are free for the time being, but when that changes, the imprisoned Jeremiah will be freer than the captive Jerusalemites, because he speaks and obeys the words of Yhwh. Jerusalem will be captive to the Babylonians, but their worse captivity will be to the consequences of their own disobedience.

- Two versions of reality. Vv. 3-10 set the stage for the events that will transpire between Jeremiah and the king's officials and between Jeremiah and the king himself. In v. 3 Zedekiah sends a delegation asking Jeremiah to pray

to "Yhwh our God for us." The narrative does not specify at this point what situation prompted Zedekiah's request, nor does it indicate that Jeremiah did anything with the request.13 Instead it shifts to what appears to be an aside about the freedom of both Jeremiah and Jerusalem. Then the narrative resumes with an unpopular word from Yhwh for the king, who (we have already been told) will not listen to Yhwh's word anyway. These three movements look as follows:

to "Yhwh our God for us." The narrative does not specify at this point what situation prompted Zedekiah's request, nor does it indicate that Jeremiah did anything with the request.13 Instead it shifts to what appears to be an aside about the freedom of both Jeremiah and Jerusalem. Then the narrative resumes with an unpopular word from Yhwh for the king, who (we have already been told) will not listen to Yhwh's word anyway. These three movements look as follows:

(i)

"And King Zedekiah sent Jehucal...to Jeremiah the prophet, saying..."

(ii)

"Jeremiah came and went...and Pharaoh's army went out from Egypt..."

(iii)

"And the word of Yhwh came to Jeremiah..."

The Hebrew syntax does not indicate a cause-and-effect relationship between Zedekiah's request for Jeremiah to pray and the departure of the Babylonians. However, the narrator puts the reader "on the ground" by juxtaposing the two events: to Zedekiah, Jerusalem, and the reader, it appears that Jeremiah prayed and Yhwh intervened. But the narrator has previously made clear that Yhwh specifically told Jeremiah not to pray ![]() for the people (7:16; 11:14; 14:11), and he gives no indication here that Jeremiah violated that command. The situation on-the-ground is encouraging to Zedekiah and Jerusalem: Egypt has rescued them! Yhwh must have answered Jeremiah's prayer! But the narrator then discloses the real situation, which is exactly the same as Yhwh and Jeremiah have been saying all along: Babylon will return and Jerusalem will fall. Jerusalem and Zedekiah see and believe what they want, but the word of Yhwh tells the reader that they are wrong. Failure to see and believe what Yhwh says will be Zedekiah's ruin before these chapters are done.

for the people (7:16; 11:14; 14:11), and he gives no indication here that Jeremiah violated that command. The situation on-the-ground is encouraging to Zedekiah and Jerusalem: Egypt has rescued them! Yhwh must have answered Jeremiah's prayer! But the narrator then discloses the real situation, which is exactly the same as Yhwh and Jeremiah have been saying all along: Babylon will return and Jerusalem will fall. Jerusalem and Zedekiah see and believe what they want, but the word of Yhwh tells the reader that they are wrong. Failure to see and believe what Yhwh says will be Zedekiah's ruin before these chapters are done.

Thus, the opening verses of chapter 37 prepare the reader for what follows by providing a hermeneutical key for reading the text, hinting at the chapters' prevailing theme, and presenting the conflicting versions of reality that faced Jerusalem and Zedekiah.

2b The Imprisonment Scenes

Five scenes involving Jeremiah's two imprisonments follow this introduction. The first two scenes narrate his first imprisonment, while the final three scenes narrate in greater detail his second imprisonment. Each of these five scenes is detailed below.

- Scene 1: Jeremiah's First Arrest/Imprisonment (37:11-16). In this first scene, the king's officials arrest Jeremiah when he leaves Jerusalem to take care of family property business (perhaps related to the field he purchased in ch. 32). Accused of desertion, Jeremiah is beaten and imprisoned in the house of Jonathan the scribe. The officials' disregard for Yhwh's word14 and their treatment of his prophet condemn them. These representatives of Jerusalem's leadership demonstrate the bankruptcy of Israel's leaders - or, in the language of chapter 23, Israel's shepherds. The scene ends with the statement, "Jeremiah was put into...a dungeon, where he remained many days" (37:16).

- Scene 2: Jeremiah's First Secret Encounter with Zedekiah / Rescue (37:17-21). In scene 2, Zedekiah sends for the imprisoned prophet and asks him privately if there has been any word from Yhwh. Jeremiah tersely gives him the word the king has already heard (but not heard;

"You'll be handed over to the Babylonians" (37:17). Certainly Zedekiah was hoping for more, but the narrator is not interested in Yhwh's familiar message; he is interested in the injustice of the prophet's sufferings, so he devotes the next three verses to Jeremiah's self-defense. The prophet demands to know what he has done to deserve imprisonment. In contrast to the lying prophets who swore Babylon would not attack, Jeremiah has said nothing untrue. He begs Zedekiah not to send him back to the house of Jonathan, where he is sure to die. In his speech Jeremiah indicts the king, the officials, and the people for his unjust imprisonment (37:18), and he laments the bankruptcy of Jerusalem's prophets. The scene ends with the statement, "So Jeremiah remained in the courtyard of the guard" (37:21).

"You'll be handed over to the Babylonians" (37:17). Certainly Zedekiah was hoping for more, but the narrator is not interested in Yhwh's familiar message; he is interested in the injustice of the prophet's sufferings, so he devotes the next three verses to Jeremiah's self-defense. The prophet demands to know what he has done to deserve imprisonment. In contrast to the lying prophets who swore Babylon would not attack, Jeremiah has said nothing untrue. He begs Zedekiah not to send him back to the house of Jonathan, where he is sure to die. In his speech Jeremiah indicts the king, the officials, and the people for his unjust imprisonment (37:18), and he laments the bankruptcy of Jerusalem's prophets. The scene ends with the statement, "So Jeremiah remained in the courtyard of the guard" (37:21). - Scene 3: Jeremiah's Second Arrest/Imprisonment (38:1-6). A second group of officials seeks the death sentence for Jeremiah on account of his message to surrender. His offense is discouraging the troops and promoting the ruin of the people rather than seeking their good.15 Zedekiah may have rescued Jeremiah from his first imprisonment, but he is powerless before his officials. Importantly here, he is also complicit in the death plot against the prophet. The Davidic King Zedekiah and his officials are corrupt; the bankrupt leadership of Jerusalem lowers the messenger of Yhwh into a cistern, where "Jeremiah sank in the mud" (38:6).16

By the end of these first three scenes, Zedekiah, the leaders of Jerusalem, and the prophets have all demonstrated the bankruptcy of their respective institutions, as described in the Zedekiah Cycle of chapters 21-24. The unchanging word of Yhwh to Jeremiah throughout his imprisonments makes clear that their fate is sealed.

In the final two scenes, the narrative slows down. The attention to details in the first and the extensive dialogue between Zedekiah and Jeremiah in the second indicate the significance of these two last scenes in the overall narrative.

- Scene 4: Jeremiah's Second Rescue (38:7-13). Scene 4 begins with the introduction of a new character, a character who "hears" (שמע), perhaps his most important trait in the text's cast of characters. Before we learn what he heard, the narrator reveals a great deal about him: Ebed-Melech is a Cushite official in the palace (38:7). As a foreigner and possibly a eunuch, he is a servant in the lower ranks of palace officials. Ebed-Melech hears (שמע) that Jeremiah has been put in the cistern, and while the king's lowly servant absorbs the implications of this injustice, the king himself is sitting in the city gate, no doubt dispensing justice to Jerusalemites. Ebed-Melech leaves the palace to tell the king the appalling news (which he already knows, of course) and to appeal for justice. The king, who did not really want Jeremiah to die, takes advantage of Ebed-Melech's public appeal and orders him to take a group17 and go rescue the prophet. Ebed-Melech takes the men and the narrator gives a stunning play-by-play of Jeremiah's rescue. The servant goes to a storage room under the treasury; he gets old rags and worn out clothes; he lets them down by ropes to Jeremiah in the cistern; he instructs Jeremiah to put the rags between his armpits and the ropes; Jeremiah does; they pull him up with the ropes; they lift him out of the cistern (38:11-13). The scene closes with the statement that "Jeremiah remained in the courtyard of the guard" (38:13).

- Scene 5: Jeremiah's Second Secret Interview (38:14-28). In the final scene Zedekiah arranges a private meeting with Jeremiah. It is the last time the prophet and king will encounter each other in the book, and their conversation is extensive. Zedekiah is desperate. He needs Jeremiah to tell him the truth and he promises not to kill him when he does.18 Jeremiah tells the king what the narrator told us at the beginning of the text: Zedekiah won't listen (שמע). But at the king's insistence, Jeremiah repeats what he has said before: surrender and live; don't surrender and die at the hands of the Babylonians (38:17-18). Zedekiah responds that he fears the pro-Babylonian Jews. Jeremiah is unfazed by the king's fear: if the king will listen to (שמע) the voice of Yhwh, he will live. It really was that simple, but alternate versions of reality were popular in Jerusalem at the time (cf. 37:3-9; see above). Zedekiah believes (and fears) something that is not true. The irony is that if the king does what he fears doing - namely, surrendering - he will live. Clinging to his fearful version of reality will leave him to sink in the mud with no Ebed-Melech to rescue him (38:21-22). The desperate dialogue ends and "Jeremiah remained in the courtyard of the guard until the day Jerusalem was captured" (38:28).

The five repeated refrains about Jeremiah's imprisonment draw our attention to the unjust suffering of Yhwh's prophet. As the intermediary between the people and God, Jeremiah sometimes identifies with the people's pain and sometimes he identifies with God's pain. He is stuck in the middle. As a suffering representative of the people, Jeremiah is a symbolic embodiment of the nation's impending demise. He is cast into a cistern to sink and die in the mud, but against all odds, he doesn't die.19 He survives and is delivered, symbolizing the nation's survival and deliverance. The destruction and dismantling of Judah will not be the end of the story.20

D EBED-MELECH AND ZEDEKIAH

Against the backdrop of Jeremiah's suffering and imprisonment stand two secondary characters: Ebed-Melech and Zedekiah. The level of detail and scope of dialogue in the final two scenes of the narrative focuses the reader's attention on these two men whose actions intersect with the fate of the prophet.

Ebed-Melech functions as a contrasting character. First, he stands in contrast to the king's officials, who mistreat and try to kill God's prophet. He steps forward to rescue Jeremiah with great tenderness (38:12). Ebed-Melech also contrasts with the Judahites more broadly. No one from Judah intercedes for Jeremiah. That task falls to a foreigner. When the entire nation of God's covenant people is at the brink of judgment for unfaithfulness, a lowly foreign official steps to the fore and does what nobody else would do. His action demonstrate his trust in Yhwh (see 39:18), and like the Recabites, Ebed-Melech is part of a faithful and pitifully small remnant.

Finally, Ebed-Melech represents a contrast to Zedekiah. Ebed-Melech rescues Jeremiah, but he is not the only rescuer in these chapters. Zedekiah rescues the prophet from his first imprisonment (37:21), an event that merits just one verse, and in the prophet's second imprisonment (which is really a death sentence), Zedekiah is complicit. But the narrator allots five verses of painstaking detail to Ebed-Melech's rescue (39:7-12). Zedekiah pales in comparison with his lowly servant. Ebed-Melech, "a servant of a king," is the true servant of Yhwh in these chapters.21 He is the one who acts righteously, when the reigning king ("Yhwh is my righteousness") does not. As the only one in these chapters who does justice and righteousness, Ebed-Melech prefigures the righteous branch foretold in Jer 23.

E CONCLUSION

The Zedekiah texts of Jeremiah are thematically related. In the first block of text (chs. 21-24), Yhwh declares the failure of Judah's institutions and pronounces his judgment on them - prophets, leaders, Davidic kings generally, and Zedekiah specifically. In the second block of Zedekiah texts (chs. 37-38), the narrator demonstrates the utter failure of Judah's leadership and sets up the narrative enactment of Yhwh's promised judgment in chapter 39. The narrative of chapters 37-38 also contrasts the failure of King Zedekiah ("Yhwh is my righteousness") with the righteousness of Ebed-Melech, a pre-figurement of the righteous branch promised in chapter 23. The judgment on Judah prophesied by Jeremiah will begin in the next chapter (39), but not until the narrator has provided hope in this narrative. Jeremiah's survival shows that judgment is not the end, because the one who acts righteously enables the prophet - a representative of the nation - to survive.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Applegate, John. "The Fate of Zedekiah: Redactional Debate in the Book of Jeremiah; Part 1." Vetus Testamentum 48 (1998): 137-60. [ Links ]

______. "The Fate of Zedekiah: Redactional Debate in the Book of Jeremiah; Part 2." Vetus Testamentum 48 (1998): 301-8. [ Links ]

Callaway, Mary C. "Telling the Truth and Telling Stories," Union Seminary Quarterly Review 44 (1991): 253-65. [ Links ]

______. "Black Fire on White Fire: Historical Context and Literary Subtext in Jeremiah 37-38." Pages 171-78 in Troubling Jeremiah. Edited by A. R. Pete Diamond, Kathleen O'Connor, and Louis Stulman. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 260. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1999. [ Links ]

Fretheim, Terence E. Jeremiah. Smyth & Helwys Bible Commentary. Macon: Smyth & Helwys, 2002. [ Links ]

Holladay, William L. Chapters 26-52. Volume 2 of Jeremiah: A Commentary on the Book of the Prophet. Hermeneia: A Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1989. [ Links ]

Holt, Else K. "The Potent Word of God: Remarks on the Composition of Jeremiah 37-44." Pages 161-70 in Troubling Jeremiah. Edited by A. R. Pete Diamond, Kathleen O'Connor, and Louis Stulman. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1999. [ Links ]

Keown, Gerald L., Pamela J. Scalies and Thomas G. Smothers. Jeremiah 26-52. Word Biblical Commentary 27. Dallas: Word, 1995. [ Links ]

Lundbom, Jack R. Jeremiah 37-52: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. Anchor Bible 21/3. New York: Doubleday, 2004. [ Links ]

Martens, Elmer A. "Narrative Parallelism and Message in Jeremiah 34-38." Pages 33-49 in Early Jewish and Christian Exegesis: Studies in Memory of William Hugh Brownlee. Edited by Craig A. Evans and William F. Stinespring. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1987. [ Links ]

Parker, Tom. "Ebed-Melech as Exemplar." Pages 253-59 in Uprooting and Planting: Essays on Jeremiah for Leslie Allen. Edited by John Goldingay. New York: T & T Clark, 2007. [ Links ]

Sternberg, Meir. The Poetics of Biblical Narrative. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985. [ Links ]

Stipp, Hermann-Josef. "Zedekiah in the Book of Jeremiah: On the Formation of a Biblical Character," Catholic Biblical Quarterly 58 (1996): 627-48. [ Links ]

Stulman, Louis. Order Amid Chaos: Jeremiah as Symbolic Tapestry. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1998; UK: The Continuum International Publishing Group, 1998. [ Links ]

Thompson, John A. The Book of Jeremiah. New International Commentary on the Old Testament. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1980. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Wendy L. Widder

Logos Bible Software, 4232 Wintergreen Cir. #260

Bellingham, WA 98226 USA

Email: wenwidder@gmail.com

1 An earlier version of this paper was presented at the annual meeting of the Evangelical Theological Society in Milwaukee, on Nov 16, 2012.

2 E.g., Mary C. Callaway, "Telling the Truth and Telling Stories," USQR 44 (1991): 253-65; Mary C. Callaway, "Black Fire on White Fire: Historical Context and Literary Subtext in Jeremiah 37-38," in Troubling Jeremiah (eds. A. R. Pete Diamond, Kathleen M. O'Connor and Louis Stulman; JSOTSup 260; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1999), 171-78; Elmer Martens, "Narrative Parallelism and Message in Jeremiah 34-38," in Early Jewish and Christian Exegesis: Studies in Memory of William Hugh Brownlee (eds. Craig A. Evans and William F. Stinespring; Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1987), 33-49; Tom Parker, "Ebed-Melech as Exemplar," in Uprooting and Planting: Essays on Jeremiah for Leslie Allen (ed. John Goldingay; New York: T & T Clark, 2007), 253-59.

3 E.g., Hermann-Josef Stipp, "Zedekiah in the Book of Jeremiah: On the Formation of a Biblical Character," CBQ 58 (1996): 627-48; John Applegate, "The Fate of Zedekiah: Redactional Debate in the Book of Jeremiah; Part 1," VT 48 (1998): 137-60, 301-8; John Applegate, "The Fate of Zedekiah: Redactional Debate in the Book of Jeremiah; Part 2," VT 48 (1998): 301-8.

4 Louis Stulman, Order Amid Chaos: Jeremiah as Symbolic Tapestry (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1998; UK: The Continuum International Publishing Group, 1998), 49.

5 Stulman, Order Amid Chaos, 49.

6 Stulman, Order Amid Chaos, 49.

7 For example, see Martens, "Narrative Parallelism," whose parallel configuration of encounters between Jeremiah and Zedekiah includes ch. 36; see also Callaway, "Telling the Truth," 262, who sees a cyclical structure consisting of a series of the "well-known story form" of encounter between prophet and king; John A. Thompson, The Book of Jeremiah (NICOT; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1980), 637, admits the possibility that chs. 37-38 offer different accounts of the same events, but he does not suggest why both accounts are needed in the narrative; William L. Holladay, Chapters 26-52 (vol. 2 of Jeremiah: A Commentary on the Book of the Prophet Jeremiah; Hermeneia; Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1989), 282, considers the two accounts to reflect different events.

8 Else K. Holt, "The Potent Word of God: Remarks on the Composition of Jeremiah 37-44," in Troubling Jeremiah (eds. A. R. Pete Diamond, Kathleen M. O'Connor and Louis Stulman; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1999), 168.

9 Martens, "Narrative Parallelism," 44, lays out a narrative parallelism of chs. 3638, in which "A [ch. 36] tells of an unsuccessful attempt to destroy the message; B [ch. 37-38] tells of an unsuccessful attempt to do away with the message." In his construction, the focus of the narrative in chs. 37-38 is a series of three interviews between the king (or a royal delegation), which correspond to three readings of the scroll before the king in ch. 36. At the conceptual level, Martens may be correct about these correspondences, but his outline of the narrative in 37-38 does not consider the structure that the narrative itself seems to dictate.

10 Meir Sternberg, The Poetics of Biblical Narrative (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985), 438.

11 Callaway, "Telling the Truth," 258, refers to five scenes punctuated by these "confinement" clauses, but she does not develop the significance of the scenes (aside from highlighting the emphasis of "imprisonment/freedom" in the narrative). Her more extended discussion of the narrative's structure argues that it's a cyclical telling "composed of scenes united by repeating themes," (262) namely the theme of encounter (and the form of similar narratives) between king and prophet: "The organizing principle of Jer 37-38 is not chronology or plot, but it may be the repeated use of a well-known story form" (264).

12 The theme of "not listening" appears extensively in Jeremiah, most immediately in ch. 36's account of Jehoiakim's scroll-burning, placing "this time in explicit continuity with the reign of Jehoiakim." See Terence E. Fretheim, Jeremiah (SHBC; Macon: Smyth & Helwys, 2002), 512.

13 Yhwh's words to Jer in 37:6 are generally seen as the response to Zedekiah's request. However, it is interesting that Zedekiah did not ask for a word from Yhwh; he asked Jeremiah to pray "pray/intercede" (פלל-HtD) for them (37:3). Cf. to the first delegation in Jer 21:2: "Inquire (דרש) of Yhwh for us, for Nebuchadnezzar king of Babylon is making war against us. Perhaps Yhwh will deal with us according to all his wonderful deeds and will make him withdraw from us." Holladay notes: "One assumes that the narrator had in mind the precedent of Hezekiah's request that Isaiah pray for the remnant of the people (2 Kgs 19:4 = Isa 37:4).

14 Note that Irijah does not "listen to" (שמע) Jeremiah (37:14).

15 Ironically, in Yhwh's word to the exiles in Jer 29:7, Jeremiah urged the people to "Seek the welfare of the city where I have sent you into exile, and pray to Yhwh on its behalf; for in its welfare you will have welfare." The welfare of God's people -exiled in Babylon or captive in Jerusalem - was dependent on Babylon's welfare.

16 This event echoes Joseph's plight ("And they took him and threw him into the pit. Now the pit was empty, without any water in it," Gen 37:24) and also makes clear that Jeremiah's predicament is even worse: his cistern has mud, into which he sinks, and we know of no one waiting in the wings to rescue him (like Reuben).

17 The MT reflects "thirty men." Many emend this to "three," based on "minor MSS evidence." See Gerald L. Keown, Pamela J. Scalise and Thomas G. Smothers, Jeremiah 26-52 (WBC; Dallas: Word, 1995), 221. I prefer Jack R. Lundbom, Jeremiah 37-52: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (AB 21/3; New York: Doubleday, 2004), 72: "Substituting 'three' for 'thirty,' suggested by Hitzig and Graf and accepted by nearly all commentators and modern Versions since (but not the NIV and NJB; cf. AV), ranks as one of the least supportable emendations in the entire book of Jeremiah and betrays a painfully unimaginative reading of the text."

18 The last time in the text that Jeremiah spoke the truth, Zedekiah let his officials throw the prophet in the cistern.

19 The cistern first appears in Jer 2, where it is a broken cistern that holds no water -a metaphor of Israel's idolatry (2:18). I suspect the metaphor of ch. 2 should perhaps influence how we read the symbolism of ch. 38, namely, just as the nation is nearly destroyed by its idolatry, so their representative is nearly destroyed in the cistern.

20 As a suffering servant of Yhwh, Jeremiah stands in a long line of suffering servants in the OT: Joseph, Job, the psalmists, Hosea, the servant of Yhwh in Isa 53.

21 No one else in the OT has this name. Holladay, Chapters 26-52, 289, comments: "It sounds like the kind of ad hoc name given to a slave whose original name no one could pronounce." He's a man without a name or credentials. Yet in the narrative, he is the only one besides the prophet who does the right thing. Cf. to other named officials, who mostly have Yahwistic names yet act contrary to anything their names stand for.