Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Old Testament Essays

versão On-line ISSN 2312-3621

versão impressa ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.26 no.2 Pretoria Jan. 2013

Aspects of demeanour in Qohelet 8:1

Aron Pinker

Maryland, USA

ABSTRACT

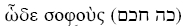

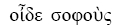

A novel approach is being suggested for the interpretation of Qoh 8:1, which views Qoh 8:1-3a as dealing with a person's demeanour. In particular, it is shown that these verses provide advice regarding one's facial and oral expression when in an audience with a high ranking official. Qohelet 8:1-3a consists of four parallel lines anchored on the two keywords:  and

and  . Recognition of the underlying structure of 8:1-3a, and similarities with Elephantine Ahiqar and Sir 13:26, points to some minor scribal errors. Correction of these errors restores the contextual sense of the verse. In particular, it is being suggested that in 8:1 the impossible

. Recognition of the underlying structure of 8:1-3a, and similarities with Elephantine Ahiqar and Sir 13:26, points to some minor scribal errors. Correction of these errors restores the contextual sense of the verse. In particular, it is being suggested that in 8:1 the impossible  should be emended to read

should be emended to read

"speak well," and the two rhetorical questions in 1a refer to facial and oral expression. A parallel line is obtained in 1b, if instead of

"speak well," and the two rhetorical questions in 1a refer to facial and oral expression. A parallel line is obtained in 1b, if instead of  one reads '

one reads ' or

or  "his mouth," assuming the ligature

"his mouth," assuming the ligature  or an extra

or an extra  , respectively. The proposed interpretation suggests that the population of Yehud had considerable access to higher officialdom during the Ptolemaic period, making the advice in 8:1 rather useful.

, respectively. The proposed interpretation suggests that the population of Yehud had considerable access to higher officialdom during the Ptolemaic period, making the advice in 8:1 rather useful.

A INTRODUCTION

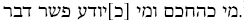

Qohelet 8:1, reading,

Who is like the wise?

And who knows the interpretation of a thing?

A person's wisdom illumines his face,

and the impudence of his face is changed

presented commentators with significant problems. The awkward nature of the verse is apparent in the indefinite nature of the questions asked, and in the answer being unrelated to these questions. It is not obvious in the first question what the criterion for comparison is, and the general sense of  in the second question obscures its meaning.

in the second question obscures its meaning.

Graetz correctly noted the nebulous nature of the first question and commentators' illusion of understanding it. He says: ״ ist in dieser Fassung nicht zu verstehen, und alle Versuche es zu erklären, beruhen auf Selbsttäuschung. Es fehlt offenbar das Prädikat."1 The questions in 1a indicate a search for a person of some qualifications, but the answer in 1b is an unrelated comment about a person's demeanour. Fox rightly says: "MT's 'and the impudence of his face is changed' is awkward, ... . It does not introduce a solution to a riddle supposedly asked in v. 1 (Gordis)."2 What could possibly be the thematic relation between 1a and 1b? The frustrating nature of 8:1 can be sensed in the words of Stuart:

״ ist in dieser Fassung nicht zu verstehen, und alle Versuche es zu erklären, beruhen auf Selbsttäuschung. Es fehlt offenbar das Prädikat."1 The questions in 1a indicate a search for a person of some qualifications, but the answer in 1b is an unrelated comment about a person's demeanour. Fox rightly says: "MT's 'and the impudence of his face is changed' is awkward, ... . It does not introduce a solution to a riddle supposedly asked in v. 1 (Gordis)."2 What could possibly be the thematic relation between 1a and 1b? The frustrating nature of 8:1 can be sensed in the words of Stuart:

The article [in

] specifies a particular man, viz. the man wise enough to make explanation. But of what? Of a

, word, maxim, apothegm, etc. But what one? I see no answer to this but one, viz. the

exhibited in the sentence or apothegm (such I take it to be) that follows. What follows this apothegm does not point us to any explanation of preceding difficulties, namely those in Chap. VII. Wisdom then will be shown, in case a proper explanation of the apothegm can be made out. In fact, it needs some wisdom to make it out; as the endless variety of opinions about the latter clause may serve to show.3

This approach, of viewing 1a as suggesting that no one except the wise could possibly understand the apothegm presented in 1b, provides structural coherence to the verse and is favored by a number of commentators.4 However, Nowack noted: "in diesem Fall würde man die Determination von  vermissen und, was die Hauptsache ist, das folgende wort 1b bedarf eines

vermissen und, was die Hauptsache ist, das folgende wort 1b bedarf eines  d. i. einer Deutung nicht."5 Moreover, nowhere in the Tanach is the meaning "apothegm, adage, maxim" for

d. i. einer Deutung nicht."5 Moreover, nowhere in the Tanach is the meaning "apothegm, adage, maxim" for  attested. While use of the article in the Qohelet corpus is somewhat inconsistent, the absence of the article here is a decided objection to this approach.6 In the immediately following vv. 2-4 and possibly v. 5, the root

attested. While use of the article in the Qohelet corpus is somewhat inconsistent, the absence of the article here is a decided objection to this approach.6 In the immediately following vv. 2-4 and possibly v. 5, the root  is used in the sense of words, or speech. Furthermore, MT speaks in 1a of "knowing"

is used in the sense of words, or speech. Furthermore, MT speaks in 1a of "knowing"  , not "making it out" or "deciphering." A person could know the meaning of an apothegm without being a student of wisdom. However, it seems that Qohelet is looking for a person who is both wise and knows the meaning of the adage in v. 1b. Why would he insist on both conditions? Finally, even if it is assumed that Qohelet means "make it out" when he uses

, not "making it out" or "deciphering." A person could know the meaning of an apothegm without being a student of wisdom. However, it seems that Qohelet is looking for a person who is both wise and knows the meaning of the adage in v. 1b. Why would he insist on both conditions? Finally, even if it is assumed that Qohelet means "make it out" when he uses ![]() why would knowing the meaning of 1b epitomize wisdom?

why would knowing the meaning of 1b epitomize wisdom?

Commentators are also divided on where v. 8:1 should be included. Many commentators think that 8:1, or at least 8:la, is the conclusion of the preceding unit.7 They view 8:la as concluding that acquisition of a complete understanding of everything is impossible, which is the point of 7:23-29.8 However, the flow of logic in unit 7:23-29 does not require a concluding remark about the limitations of a person's wisdom.9 Attachment of v. 1 to unit 7:23-29 would be gratuitous.

Some claim 8:1 belongs to some glossator. For instance, Barton following Siegfried and McNeile denies Qohelet authorship of 8:1. He says: "This verse, which consists of two gnomic sayings, has been rightly regarded by Siegfried and McNeile as from the hand of the Hokma glossator."10 Unfortunately Barton does not explain why the Hokma glossator was compelled to make this addition. Delitzsch takes a somewhat intermediate position, saying: "Wenn nun v. 1 nicht als außer Zusatz stehender Spruch gelten soll, so wird er sich gewissermaßen prologisch zum Folgenden Verhalten."11

Seow is definite in stating that 8:1 has a natural place as the leading verse of unit 8:1-17. 12 He says,

...the rhetorical question 'who knows' anticipates the assertion that 'no one knows' (v 7) and, eventually, also the admission at the end of the passage that the wise who think they know are not able to discover anything (v 17). In short, the references to the wise and their quest for knowledge frame the literary unit.13

On the other hand, Crenshaw seems to lean toward splitting 8:1, and linking 1a with the preceding text and 1b with the following text. He says,

The use of the equivalent term

in Gen. 40:5 in the setting of discovering the answer, as well as the meaning of

in Egyptian Aramaic, suggests that a relationship with what precedes is not out of the question.14 However, the second part of the verse anticipates the discussion of behaviour in the royal court (8:2). Probably the reference to one's countenance concerns conduct before the king and his officials.15

In addition to the difficulties regarding 8:1 that have been mentioned, commentators were also challenged by the referent of ![]() in 1bα and 1bß. Do the two

in 1bα and 1bß. Do the two ![]() in v. 1b have the same referent? Is this referent

in v. 1b have the same referent? Is this referent

is the referent of

is the referent of ![]() in 1bß and a man's wisdom brightens his face, why was it harsh in the first place? If the two

in 1bß and a man's wisdom brightens his face, why was it harsh in the first place? If the two ![]() ו in v. 1b have different referents what are they? How does 1b relate to 7:3 and 7:2, where seemingly a somber or sad face is suggested as being the proper demeanour for the wise?

ו in v. 1b have different referents what are they? How does 1b relate to 7:3 and 7:2, where seemingly a somber or sad face is suggested as being the proper demeanour for the wise?

The purpose of this paper is to provide answers to the questions that were posed, assuming the unit intends to advise Judeans on proper and useful behaviour when appearing before rulers. In this context, it is being suggested that the impossible  should be emended to read

should be emended to read  "speak well." Thus, in 1a the two questions refer to facial and oral expression. A parallel response is obtained in 1b, if instead of

"speak well." Thus, in 1a the two questions refer to facial and oral expression. A parallel response is obtained in 1b, if instead of  one reads

one reads  "his mouth," assuming the ligature

"his mouth," assuming the ligature  , or

, or  assuming an extra נ. It will be argued that these minor emendations more aptly fit the context.

assuming an extra נ. It will be argued that these minor emendations more aptly fit the context.

B ANALYSIS

1 Early Exegesis

It seems that already the ancient versions encountered considerable difficulty with 8:1. This can be sensed from the various implicit emendations that their translations contain. The Septuagint apparently adds  to 1aα rendering

to 1aα rendering

("who knows the wise?") and drops the

("who knows the wise?") and drops the ![]() of comparison from

of comparison from  . The rendering of

. The rendering of ![]() by

by ![]() ("interpretation of the word, or saying") gives 1aß some definiteness, though "saying" is not in the semantic field of

("interpretation of the word, or saying") gives 1aß some definiteness, though "saying" is not in the semantic field of  and "word" gives a meaningless expression. Aquila reads

and "word" gives a meaningless expression. Aquila reads  instead of

instead of , and so does Symmachus

, and so does Symmachus

.16 However, the phrase

.16 However, the phrase  never occurs in the Tanach, nor do the sub-phrases

never occurs in the Tanach, nor do the sub-phrases ![]() and

and  . The Targum understands v. 1 as the challenge to comprehend God's word as it appears in the scriptures, saying: "who is the wise man, who can stand before the wisdom of God, and fathom the words of the prophets?" The Targum is even more definite than the Septuagint regarding

. The Targum understands v. 1 as the challenge to comprehend God's word as it appears in the scriptures, saying: "who is the wise man, who can stand before the wisdom of God, and fathom the words of the prophets?" The Targum is even more definite than the Septuagint regarding ![]() ,it homiletically renders

,it homiletically renders  by

by![]() ("words in the prophets").

("words in the prophets").

The Septuagint also reads ![]() ("will be hated" =

("will be hated" =  instead of

instead of ![]() ("will be changed"), and so does the Peshitta

("will be changed"), and so does the Peshitta  .17 On the other hand the Targum's

.17 On the other hand the Targum's ![]() reflects the MT reading

reflects the MT reading ![]() "will be changed," where the verb

"will be changed," where the verb ![]() "change" is conjugated like

"change" is conjugated like ![]() verbs with a segol.18 The Vulgate's commutabit also implies the reading

verbs with a segol.18 The Vulgate's commutabit also implies the reading![]() . The Vulgate's rendition of 1bß by et potentissimus faciem illius commutabit ("and the omnipotent will change his face") leaves one with more questions than answers.

. The Vulgate's rendition of 1bß by et potentissimus faciem illius commutabit ("and the omnipotent will change his face") leaves one with more questions than answers.

Unlike the MT, where  is the noun "boldness, impudence," the versions read the adjective

is the noun "boldness, impudence," the versions read the adjective  , "harsh, impudent" (Deut 28:50, Prov 7:13).19 As Gordis noted, this reading would necessitate the change of

, "harsh, impudent" (Deut 28:50, Prov 7:13).19 As Gordis noted, this reading would necessitate the change of  .20 The changes in the Versions do not imply use of a different Vorlage than MT, but they do reflect the challenges that 8:1 posed to them.

.20 The changes in the Versions do not imply use of a different Vorlage than MT, but they do reflect the challenges that 8:1 posed to them.

Classical Jewish exegetes also struggled with 8:1. Rashi (1040-1105) assumes that in 1aα the word "important" (![]() ) is implied, and in 1aß the word

) is implied, and in 1aß the word ![]() means "interpretation" and/or "compromise." It seems that Rashi understands

means "interpretation" and/or "compromise." It seems that Rashi understands ![]() in the sense of "fearful expression, frightening sight" exploiting Ex 34:30, which describes the shining face of Moses and the Israelites' fear to approach him. Unfortunately, adding

in the sense of "fearful expression, frightening sight" exploiting Ex 34:30, which describes the shining face of Moses and the Israelites' fear to approach him. Unfortunately, adding![]() does not make the question in 1aα more definite. Actually, in 9:15-16 Qohelet complains that the wise are not that important and their wisdom is not appreciated. Furthermore, the generality of

does not make the question in 1aα more definite. Actually, in 9:15-16 Qohelet complains that the wise are not that important and their wisdom is not appreciated. Furthermore, the generality of ![]() leaves "interpretation of a thing" or "compromise of a thing" nebulous.

leaves "interpretation of a thing" or "compromise of a thing" nebulous.

Rashbam (c. 1085-1174) also assumes an implied ![]() in 1aα. He understands

in 1aα. He understands ![]() in the sense of "strength." It seems that Rashbam assumes that wisdom makes a person's face shine and brings him joy. This joy then increases the shining of the face. Rashbam's approach amounts to reading into the text a two stage process, which can be hardly justified.

in the sense of "strength." It seems that Rashbam assumes that wisdom makes a person's face shine and brings him joy. This joy then increases the shining of the face. Rashbam's approach amounts to reading into the text a two stage process, which can be hardly justified.

Ibn Ezra (1089-c. 1164) notes that sometimes in biblical texts a word or letter is implied.21 He suggests that this might be the case in v. 1, which should be read:  22 He also raises the possibility that v. 1 is a question and an answer: "Who is as the wise? One who knows the meaning of a thing." This would require deletion of the

22 He also raises the possibility that v. 1 is a question and an answer: "Who is as the wise? One who knows the meaning of a thing." This would require deletion of the![]() from

from ![]() and addition of a

and addition of a ![]() to

to ![]() . Ibn Ezra tries to imbue

. Ibn Ezra tries to imbue  with some definiteness by explaining that it means understanding the utility of everything and why it is so

with some definiteness by explaining that it means understanding the utility of everything and why it is so

. While this sounds reasonable, it is not anchored in the text. He also raises the possibility that

. While this sounds reasonable, it is not anchored in the text. He also raises the possibility that![]() is the result of metathesis and should be read

is the result of metathesis and should be read ![]() "make distinct, declare, interpret." In a vein similar to that of Rashbam, Ibn Ezra suggests that acquired wisdom would induce humility, and will remove anger and arrogance from a person's face. Again, such a two stage process is not indicated in the text.

"make distinct, declare, interpret." In a vein similar to that of Rashbam, Ibn Ezra suggests that acquired wisdom would induce humility, and will remove anger and arrogance from a person's face. Again, such a two stage process is not indicated in the text.

Qara (second part of 11th to first part of 12th century) expands the range of possible implications in 1aα by admitting ![]() , thinks," a word play on

, thinks," a word play on ![]() . This in effect undermines Rashi's suggestion since it shows that many attributes can serve as the referent of the question in 1aα. Qara also undermines Ibn Ezra's explanation of

. This in effect undermines Rashi's suggestion since it shows that many attributes can serve as the referent of the question in 1aα. Qara also undermines Ibn Ezra's explanation of ![]() suggesting that it refers to "any question that is asked"

suggesting that it refers to "any question that is asked"  . In his view, acquisition of knowledge changes a person's face, making it bright and happy.

. In his view, acquisition of knowledge changes a person's face, making it bright and happy.

Sforno (1470-1550) assumes that the question in 1aα alludes to the wise in 7:28, and in 1aß ![]() refers to the morals of mythological stories. He understands the change occurring in 1bß as being that of mind controlling desires. Sforno's explanation, as well as that of the preceding Jewish commentators, highlights their unsuccessful attempts to accord v. 1 some definiteness and internal coherence. Their failures stem from resorting to extraneous elements for explaining the verse, rather than exploiting the text at hand.

refers to the morals of mythological stories. He understands the change occurring in 1bß as being that of mind controlling desires. Sforno's explanation, as well as that of the preceding Jewish commentators, highlights their unsuccessful attempts to accord v. 1 some definiteness and internal coherence. Their failures stem from resorting to extraneous elements for explaining the verse, rather than exploiting the text at hand.

2 Early Modern Exegesis

Qohelet 8:1 continued to challenge commentators to this day. Modern commentators, as their predecessors, continued to imbue 8:1 with extraneous notions. For instance, Ginsburg says regarding 1a: "The next lesson which this common sense view of life teaches is gentle submission. He who is truly wise, who understands the import of this matter, or of this view of life, has no com-peer."23 He explains that 1b gives the reason for the sentiment expressed in the former clause. Such a wise person has no equal "because his wisdom, or the prudent view of life according to which he regulates his conduct, makes him cheerful, and teaches him submission, to endure that which he cannot cure."24 One would be hard pressed to detect in our verse any textual references to "gentle submission" in life.

Hengstenberg considers 1aß the reason for 1aα. No one is equal to the wise man "because wisdom leads us into the nature, the essence of things, and thus furnishes a basis for right practical conduct."25 In his view, "The reason of the joy afforded by wisdom may be found in the insight it gives into the nature of things, specially, into the providence of God; and in the assurance and decision with which, as a consequence, we can regard the practical question of life."26 This wisdom changes the hard and rigid features of one's face, which express boldness and impudence. Hengstenberger, too, is reading much extraneous material into the Qoh 8:1.

A similar understanding of 1a is adopted by Delitzsch. He finds 1b being the reason for 1a and parallel to it. Delitzsch says:

Was nun 1b folgt könnte durch begründendes

eingeführt sein, es stellt sich aber nach der Weise des synonymen Parall. Mit 1a auf gleiche Linie, indem daß der Weise so hoch steht und Niemand wie er das Innere der Dinge durchschaut in andere Form wiederholt wird: 'die Weisheit macht sein Angesicht licht' ist also nach Ps 119,130 und

Ps. 19,9 zu verstehen, die Weisheit zieht den Schleier von seinem Angesicht und macht es helle, denn die Weisheit verhält sich zur Thorheit wie Licht zur Finsternis 2,13. Indes zeigt der Gegens.

daß nicht blos die Lichtung des Blickes, sondern im Allgem. Jene geistige und ethische Verklärung des Angesichts gemeint ist, an welcher wir sofort, wenn dieses auch nicht an sich schön sein sollte, den gebildeten und über das Gemeine hinausgerückten Menschen erkennen.27

However, it is doubtful that the highly intellectual attributes described in 1a (according to Delitzsch) are on a par with the physical expressions of the face in 1b.

Who is as the wise man? Plumptre believes that "[w]e find the probable explanation of this suggestive question in the fact that the writer veils a protest against despotism in the garb of the maxims of servility."28 However, this fact is not a fact. Plumptre understands 1bß expressing the transformation by culture of the coarse ferocity of ignorance, akin to Ovid's lines: "To learn in truth the nobler arts of life, Makes manners gentle, rescues them from strife."29

In Stuart's view, the questions in 1bα amount to: "Who, like a wise man, can explain the difficulties, or solve the questions that arise in respect to wisdom?" He understands the two last clauses as constructed alike and stating: "The wisdom of a man enlightens his face, and haughtiness or impudence disfigures his face."30 Stuart also imbues 1a with his own notions. Unfortunately, the comparison in 1b suggested by Stuart is not antithetical, and Stuart is aware of that. Moreover, knowing about a wise man's ability to deal with fundamental problems of wisdom has nothing to do with facial expression. In other words, v. 1b can stand alone; it does not need 1a, as interpreted by Stuart.

Wildeboer views 1a as praise of wisdom-its indispensability, and 1b as description of two of its effects. He takes 1bα as referring in general to both of those effects: wisdom illumines one's countenance (sie erleuchtet das Angesicht) and wisdom makes the face bright (macht das Gesicht hell). The first effect is explicated in 1a, which Wilderboer assumes speaks about wisdom giving a clear and confident view (sie gibt einen klaren, sicheren Blick) as in Qoh 2:14, Ps 19:9 and 119:130. The second effect is explicated in 1bß, suggesting that wisdom changes the coarseness of expression (frechen, rohen Gesichtsausdruck).31 This explanation is too complicated to be obvious to the reader. Moreover, Wilderboer does not textually substantiate his assertions regarding wisdom's indispensability and its provision of a clear view.

Graetz finds it significant for the exegesis of 8:1 that the Septuagint and Aquila give essentially the same translation of 1aα. According to this indication the original construction might have been  ? In his view the meaning of

? In his view the meaning of ![]() was misunderstood by all. It is not connected with

was misunderstood by all. It is not connected with ![]() , but means "compromise," as in NH

, but means "compromise," as in NH ![]() lukewarm." Only the wise know how to find a compromise in a conflict. Graetz suggests that Qohelet specifically refers to a conflict arising from one's obligations to a ruler according to a loyalty oath, and participation in morally repugnant acts in case he is a tyrant. Graetz adopts the Septuagint's reading ("will be hated" =

lukewarm." Only the wise know how to find a compromise in a conflict. Graetz suggests that Qohelet specifically refers to a conflict arising from one's obligations to a ruler according to a loyalty oath, and participation in morally repugnant acts in case he is a tyrant. Graetz adopts the Septuagint's reading ("will be hated" =![]() ) and consequently considers 1b an antithetical parallelism, a wise man is liked and an impudent man is hated.32 In this case one wonders why Qohelet adds in 1a the word

) and consequently considers 1b an antithetical parallelism, a wise man is liked and an impudent man is hated.32 In this case one wonders why Qohelet adds in 1a the word![]() Without it the text reads better and is less problematic. Moreover, the conflict described by Greatz has no basis in the text. Finally, nowhere else has it been asserted that a wise man is liked. Reading

Without it the text reads better and is less problematic. Moreover, the conflict described by Greatz has no basis in the text. Finally, nowhere else has it been asserted that a wise man is liked. Reading ![]() ("will be hated") destroys the parallelism between 1aα and 1aß, since "hate" is not the opposite of "a bright face."

("will be hated") destroys the parallelism between 1aα and 1aß, since "hate" is not the opposite of "a bright face."

3 Recent Modern Exegesis

More recent exegesis did not produce new understanding of 8:1. For instance, Gordis surprisingly does not discuss 1a, except the word ![]() . He suggests that 1b deals with a royal court setting, and in 1bα "the stress is not upon the gracious act, but upon appearing gracious toward one's associates in court,whatever may be one's real feelings. A court official cannot display his dislikes or anger at will. His wisdom will impel him to maintain his suavity and poise under all circumstances."33 The next statement is a nuance of 1bα, "A courtier will avoid the appearance of being overbold and aggressive. His good sense will lead him to disguise such an expression."34 In Gordis' view wisdom does not introduce lasting changes of demeanour, but rather enables control and manipulation of one's feelings. It is doubtful that such a sense can be deduced from the terms

. He suggests that 1b deals with a royal court setting, and in 1bα "the stress is not upon the gracious act, but upon appearing gracious toward one's associates in court,whatever may be one's real feelings. A court official cannot display his dislikes or anger at will. His wisdom will impel him to maintain his suavity and poise under all circumstances."33 The next statement is a nuance of 1bα, "A courtier will avoid the appearance of being overbold and aggressive. His good sense will lead him to disguise such an expression."34 In Gordis' view wisdom does not introduce lasting changes of demeanour, but rather enables control and manipulation of one's feelings. It is doubtful that such a sense can be deduced from the terms  ("will brighten") and ("will be changed").

("will brighten") and ("will be changed").

Crenshaw explains that in 8:1 "Two rhetorical questions introduce a traditional wisdom saying. The first question asserts that no one is like a sage, and the second denies that anyone knows the meaning of a matter."35 It would seem that in this explanation the two rhetorical questions contradict each other. Cren-shaw does not elucidate this matter. As Gordis, Crenshaw too considers 1bα as referring to manipulative behaviour; however in 1bß he detects a fundamental change. He says: "wisdom leads the wise to dissimulate, to hide their true feelings under a pleasant demeanour. The second image, a changed countenance, shows wisdom transforming an angry look into a gentler and less threatening one (cf. Sir 13:24).36

one (cf. Sir 13:24).36

Fox also leaves 1a unexplained. He considers 1b as describing the advantages of wisdom in the presence of a despot. Fox observes: "A man's wisdom will not make him actually happy in the presence of a despot, but it does teach him to affect a cheerful demeanour so as to ingratiate himself with whoever is in power and disarm his suspicions. Impudence, on the other hand, betrays itself by a scowl, and this could very well cause trouble with the ruler."37 If Fox is correct, then the text should have been ![]() .

.

In Seow's opinion the pair of rhetorical questions in 1a introduces the sayings of the wise in 1b-5a, and 1b asserts that wisdom causes one to display a pleasant appearance and to change one's impudent look. The theme of 8:1 according to Seow is,

Before a superior, especially someone whose wrath is swift, it is wise not to display any animosity. Instead, despite one's feelings, it is smart to act pleasantly. The point seems to be that people ought not to incur the king's disfavor, for the king acts with the same arbitrary power as a high-god.38

While Seow's paraphrase expresses a useful thought, but it is not anchored in the MT.

The most extensive emendation of 8:1 has been suggested by Ginsberg. He makes the following three emendations: (1)![]() in 1aα; (2) reads

in 1aα; (2) reads![]() (or

(or![]() ) instead of

) instead of ![]() in 1bα; and, (3) vocalizes

in 1bα; and, (3) vocalizes  the final word in 1bß.39 With these emendations Ginsberg obtains the meaning: "Who here is wise (or, or is acquainted with-see immediately), and who knows the meaning of the saying: 'A man's pleasure lights up his face (cf. Prov 15:13 and the paradox in Koh 7:3), but fierceness darkens his face (cf. Job 14:20; Lam 4:1; Dan 5:6; 7:28)'?" However, the suggested mechanism, by which the original Aramaic

the final word in 1bß.39 With these emendations Ginsberg obtains the meaning: "Who here is wise (or, or is acquainted with-see immediately), and who knows the meaning of the saying: 'A man's pleasure lights up his face (cf. Prov 15:13 and the paradox in Koh 7:3), but fierceness darkens his face (cf. Job 14:20; Lam 4:1; Dan 5:6; 7:28)'?" However, the suggested mechanism, by which the original Aramaic ![]() was rendered as the Hebrew

was rendered as the Hebrew![]() , is not convincing. It has been noted already, that the meaning "apothegm, adage, maxim, saying" for

, is not convincing. It has been noted already, that the meaning "apothegm, adage, maxim, saying" for![]() is nowhere attested in the Tanach. Also, the sources cited in support of the meaning "darkens" for

is nowhere attested in the Tanach. Also, the sources cited in support of the meaning "darkens" for  are not compelling. Ginsberg takes 8:2 being the answer to the question posed in 8:1; Qohelet answers a question about a proverb with a proverb. However, it is difficult to see how this could be the case, if Ginsberg rendition of 8:1 is correct and 8:2 means "Heed the face of a king, and in the matter of an oath of God be not over hasty." The watching of a king's face could only make sense if 8:1 is first understood.

are not compelling. Ginsberg takes 8:2 being the answer to the question posed in 8:1; Qohelet answers a question about a proverb with a proverb. However, it is difficult to see how this could be the case, if Ginsberg rendition of 8:1 is correct and 8:2 means "Heed the face of a king, and in the matter of an oath of God be not over hasty." The watching of a king's face could only make sense if 8:1 is first understood.

Text analysis focused on the unusual phrase  , the meaning of the phrases

, the meaning of the phrases ![]()

![]() and

and ![]() , and the vocalization of

, and the vocalization of ![]() and

and ![]() . BHS notes that the reading

. BHS notes that the reading ![]() has been proposed in an effort to create synonymous parallelism with 1aß. It is notable that the expressions

has been proposed in an effort to create synonymous parallelism with 1aß. It is notable that the expressions ![]() and

and ![]() occur several times in the Tanach (Hos 14:10, Ps 107:43, Jer 9:11), but not the comparative

occur several times in the Tanach (Hos 14:10, Ps 107:43, Jer 9:11), but not the comparative ![]() 40. The abnormal

40. The abnormal ![]() instead of the normal

instead of the normal ![]() , with the

, with the ![]() ה dropped and its vowel under the

ה dropped and its vowel under the ![]() comparison, is not of infrequent occurrence, especially in later books (Ezek 40:25; 47:22; 2 Chr 10:7; 25:10; 29:7; Neh 9:19; 12:38; 1 Sam 13:21; Ps 36:6).41 It has been suggested that 1aα should be parsed

comparison, is not of infrequent occurrence, especially in later books (Ezek 40:25; 47:22; 2 Chr 10:7; 25:10; 29:7; Neh 9:19; 12:38; 1 Sam 13:21; Ps 36:6).41 It has been suggested that 1aα should be parsed ![]() . Seow believes that the Greek traditions had a Vorlage that read

. Seow believes that the Greek traditions had a Vorlage that read![]() instead of 42

instead of 42 ![]() . However, the phrase

. However, the phrase ![]() never occurs in the Tanach, nor do occur the sub-phrases

never occurs in the Tanach, nor do occur the sub-phrases![]() and

and ![]() . Zapletal thinks that the original reading might have been just

. Zapletal thinks that the original reading might have been just ![]() 43.

43.

The word ![]() occurs in biblical Hebrew only in Qoh 8:1 but frequently in the Aramaic portion of Daniel (Dan 2:4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 16; 2:4, 6, 15, 21; 5:12, 16, etcetera.), mostly in contexts of mantic wisdom.44 It occurs frequently in the Qumran texts, where it refers to the interpretation of biblical texts.45 Most commentators take it to be an Aramaic loan word related to BH

occurs in biblical Hebrew only in Qoh 8:1 but frequently in the Aramaic portion of Daniel (Dan 2:4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 16; 2:4, 6, 15, 21; 5:12, 16, etcetera.), mostly in contexts of mantic wisdom.44 It occurs frequently in the Qumran texts, where it refers to the interpretation of biblical texts.45 Most commentators take it to be an Aramaic loan word related to BH ![]() and

and ![]() , and render it "interpretation."46 In Daniel, the phrase

, and render it "interpretation."46 In Daniel, the phrase ![]() "meaning of the words" (5:15, 26) and

"meaning of the words" (5:15, 26) and ![]() "meaning of the thing" (7:16) are closest to

"meaning of the thing" (7:16) are closest to ![]() in Qoh 8:1, and they refer to definite items or events. Qohelet uses

in Qoh 8:1, and they refer to definite items or events. Qohelet uses![]() in the sense of "word, thing" in 1:1, 8, 10, 5:1, 2, 6, 6:11, 7:8, 21, 8:1, 3, 4, 5, 9:16, 17, 10:12, 13, 14, 20, 12:10, 11, 13, and three times in the form

in the sense of "word, thing" in 1:1, 8, 10, 5:1, 2, 6, 6:11, 7:8, 21, 8:1, 3, 4, 5, 9:16, 17, 10:12, 13, 14, 20, 12:10, 11, 13, and three times in the form ![]() . In the immediately following vv. 2-4 and possibly v. 5, the root

. In the immediately following vv. 2-4 and possibly v. 5, the root ![]() is used in the sense of words, or speech.

is used in the sense of words, or speech.

The phrase![]() has been interpreted by some commentators "gives a clearer view" (Ps 19:9, 119:130), and by some "makes the face pleasant." Most commentators understand

has been interpreted by some commentators "gives a clearer view" (Ps 19:9, 119:130), and by some "makes the face pleasant." Most commentators understand![]() as reflecting the "brightness" which appears on a wise man's face when he correctly analyzes a matter (

as reflecting the "brightness" which appears on a wise man's face when he correctly analyzes a matter (![]() ). The concept "a bright face" or the effect of "brightening one's face, or eyes" is mentioned in Num 6:25; Isa 60:5; Ps 4:7; 19:9; 34:6; Prov 16:15; Job 29:24, etcetera. However, expressions similar to

). The concept "a bright face" or the effect of "brightening one's face, or eyes" is mentioned in Num 6:25; Isa 60:5; Ps 4:7; 19:9; 34:6; Prov 16:15; Job 29:24, etcetera. However, expressions similar to![]() are used in the Tanach only in reference to the deity (Ps 31:17; 67:2; 80:4, 8, 20; 119:135, Dan 9:17). A somewhat more remote use of "a bright face" in reference to a human is Prov 16:15, "in the light of the king's countenance is life," and Sir 13:26,

are used in the Tanach only in reference to the deity (Ps 31:17; 67:2; 80:4, 8, 20; 119:135, Dan 9:17). A somewhat more remote use of "a bright face" in reference to a human is Prov 16:15, "in the light of the king's countenance is life," and Sir 13:26, ![]()

![]() .

.

It was noted that the Versions read ![]() (adjective) instead of MT

(adjective) instead of MT ![]() (noun).47 This approach has been adopted by many. For instance, Delitzsch says that

(noun).47 This approach has been adopted by many. For instance, Delitzsch says that ![]() :

:

... ohne Zweifel nach

Dt. 28,50. Dan. 8,23 und

Spr. 7,13 oder

Spr. 21,29 zu verstehen ist, so daß also

das selbe was nachbiblische

Starrheit, Härte, Roheit, des Gesichts = Frechheit, Unverschämtheit, Rücksichtslosigkeit.48

Ginsburg argues that Deut 28:50 shows ![]() cannot mean "the impudence of his face," since one could not say that the enemy is impudent to the young, and therefore

cannot mean "the impudence of his face," since one could not say that the enemy is impudent to the young, and therefore ![]() must mean a foe treating with "vigor" both old and young.49 Gordis observes that "The change is unnecessary. The suffix in

must mean a foe treating with "vigor" both old and young.49 Gordis observes that "The change is unnecessary. The suffix in ![]() refers back to

refers back to ![]() (so most comm.) or possibly may be rendered impersonally as 'one's boldness.'"50 BHK raised the possibility that

(so most comm.) or possibly may be rendered impersonally as 'one's boldness.'"50 BHK raised the possibility that ![]() should be emended to

should be emended to ![]() . Such an emendation is orthographically untenable.

. Such an emendation is orthographically untenable.

Comparison of 2 Kgs 25:9 with Jer 52:33 shows that  is the result of a

is the result of a  confusion.51 Indeed many Hebrew MSS have

confusion.51 Indeed many Hebrew MSS have ![]() . The revocalization

. The revocalization  "has been suggested to harmonize with the Active

"has been suggested to harmonize with the Active ![]() 52. This emendation is not necessary, since the Passive gives a more fitting sense.53 The idiom

52. This emendation is not necessary, since the Passive gives a more fitting sense.53 The idiom![]()

![]() "to change (one's) face" = "to change (one's) expression" is attested in Job 14:20, Sir 12:18 (

"to change (one's) face" = "to change (one's) expression" is attested in Job 14:20, Sir 12:18 (![]()

![]() ), and 13:24 (

), and 13:24 (![]()

![]() ). Knobel raised the possibility that

). Knobel raised the possibility that ![]() reflects the Arabic šana', "brighten, lighten." He says: "Vielleicht könnte man auch das arab. šana' splenduit, luxit vergleichen und übersetzen: der Unmuth seines Angesichts wird heller, geht in Heiterkeit über."54 This suggestion would only introduce redundancy into 1b.

reflects the Arabic šana', "brighten, lighten." He says: "Vielleicht könnte man auch das arab. šana' splenduit, luxit vergleichen und übersetzen: der Unmuth seines Angesichts wird heller, geht in Heiterkeit über."54 This suggestion would only introduce redundancy into 1b.

The awkwardness of ![]() in the following v. led a number of commentators to include it in 8:1.55 The words

in the following v. led a number of commentators to include it in 8:1.55 The words ![]()

![]() are then read as the single word

are then read as the single word  "one changes it." This emendation requires assuming that dittography of א and י/ו confusion occurred. Dahood thinks that the confusion between

"one changes it." This emendation requires assuming that dittography of א and י/ו confusion occurred. Dahood thinks that the confusion between ![]() and

and ![]() arose from a dittography of א in an original Phoenician orthography

arose from a dittography of א in an original Phoenician orthography ![]() .56

.56

It has been suggested that the second half of the verse is a quotation of a proverb praising wisdom, and that the order of 1a and 1b should be reversed, in order to make the verse more meaningful. The flow of logic would be: praise of wisdom, followed by the comment that truly wise men are few and far between. Verse 8:1 would then be linked to the preceding section.57

A review of the exegesis on Qoh 8:1 shows considerable agreement on the interpretation of its keywords and phrases. The major difficulties that commentators encountered were of a thematic nature: giving meaning to 1a; deciphering the inner structure of 1b; and, identifying the logical continuity of the verse. In the following, a novel approach for resolving these difficulties will be proposed.

C PROPOSED SOLUTION AND CONTEXT

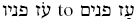

It has been noted that many commentators viewed 8:1 as the beginning of the unit that follows. This position is bolstered by the observation that unit 8:1-4 deals with a wise person's demeanour and his behaviour in an audience with a king or ruler. It was easy in Qohelet's time for a person to irritate a capricious ruler and incur his wrath. A person who knows to wisely behave in such circumstances is considered by Qohelet to be unique. In this context, v. 1 is a general introductory statement about demeanour, particularly facial and oral expression, which is followed by three verses dealing with specific interactions with the king, or someone of equivalent authority.58

The general statement in v. 1 opens with the question "Who is as the wise?" which intrigues the reader in its indefiniteness and challenge, initiating contemplation and anticipation. Qohelet's reference set for this question will become clear only later, after v. 2 has been read, and particularly after the structure of 8:1-3a becomes obvious. The understanding of the second question, as it appears from the analysis, depends on the meaning of ![]() and is disputed.

and is disputed.

Ginsburg noted that the phrase ![]() exactly corresponds to the Hebrew

exactly corresponds to the Hebrew  in 1 Sam 16:18.59 The phrase

in 1 Sam 16:18.59 The phrase  is usually given the sense "skilled in speech."60 Delitzsch rightly observed, "Ginsburg vergleicht 1S. 16,18., was aber nicht den Sachkundigen, sondern den Redekundigen bedeutet."61 Indeed, the parallelism of

is usually given the sense "skilled in speech."60 Delitzsch rightly observed, "Ginsburg vergleicht 1S. 16,18., was aber nicht den Sachkundigen, sondern den Redekundigen bedeutet."61 Indeed, the parallelism of  and

and ![]() in v. 4 suggests that some confusion with respect to vocalization of

in v. 4 suggests that some confusion with respect to vocalization of ![]() occurred in the unit 8:1-4 and perhaps elsewhere in the Qohelet corpus.62 For instance, in v. 3

occurred in the unit 8:1-4 and perhaps elsewhere in the Qohelet corpus.62 For instance, in v. 3  is awkward in its indefiniteness while

is awkward in its indefiniteness while  makes good sense (cf. Josh 23:14-15); in 1:8 (see Rashi) the reading

makes good sense (cf. Josh 23:14-15); in 1:8 (see Rashi) the reading  is supported by the paronomasia; in 1:10 Tur-Sinai suggest reading

is supported by the paronomasia; in 1:10 Tur-Sinai suggest reading  instead of

instead of  63 in 5:1-2

63 in 5:1-2  clearly refers to speech; etcetera.64 These instances demonstrate that it is impossible to exclude in 1aß the understanding of

clearly refers to speech; etcetera.64 These instances demonstrate that it is impossible to exclude in 1aß the understanding of  in the sense of

in the sense of

If the reading  is adopted, the noun

is adopted, the noun![]() is awkward; an adjective would give a better fit. Such an adjective can be obtained from

is awkward; an adjective would give a better fit. Such an adjective can be obtained from ![]() by transposing the first two letters. The phrase

by transposing the first two letters. The phrase  "speak nicely" makes good sense. It is akin to the expression

"speak nicely" makes good sense. It is akin to the expression ![]() in Gen 49:21 and reflects Qohelet's principle in 3:7b about there being a time for keeping quiet and a time for talking. The first part of v. 1 then says: Who is as the wise? Who knows to speak nicely? It is notable that a wise person's capability to speak nicely is highlighted by Qohelet (9:17; 10:12 and 12:10).

in Gen 49:21 and reflects Qohelet's principle in 3:7b about there being a time for keeping quiet and a time for talking. The first part of v. 1 then says: Who is as the wise? Who knows to speak nicely? It is notable that a wise person's capability to speak nicely is highlighted by Qohelet (9:17; 10:12 and 12:10).

Clearly, 1bα speaks about the effect that wisdom has on a person's demeanour. It cannot mean a wise man's capability to manipulate his facial expression. In that case Qohelet would have used the ל of purpose with the infinitive ![]() (cf. 5:5). Qohelet says that wisdom brightens one's face, gives it a pleasant expression. Various opinions have been offered on what

(cf. 5:5). Qohelet says that wisdom brightens one's face, gives it a pleasant expression. Various opinions have been offered on what![]() specifically refers to. Demeanour has historically played an important role in establishing a person's veracity, and is consequently often applied to a witness during a trial. Demeanour evidence is quite valuable in shedding light on the credibility of a witness. This is one of the reasons why personal presence at trial is considered to be of paramount importance, and has great significance concerning the Hearsay rule. To aid a judge or jury in determining whether to believe or not believe particular testimony, they are provided with the opportunity to hear statements directly from a witness in court whenever possible. It is likely that Qohelet refers to this aspect of a pleasant demeanour-one associated with truthfulness.

specifically refers to. Demeanour has historically played an important role in establishing a person's veracity, and is consequently often applied to a witness during a trial. Demeanour evidence is quite valuable in shedding light on the credibility of a witness. This is one of the reasons why personal presence at trial is considered to be of paramount importance, and has great significance concerning the Hearsay rule. To aid a judge or jury in determining whether to believe or not believe particular testimony, they are provided with the opportunity to hear statements directly from a witness in court whenever possible. It is likely that Qohelet refers to this aspect of a pleasant demeanour-one associated with truthfulness.

The difficult 1bß deals with a person's tone of speech. This view is based on the assumption that ![]() in 1bα affected the reading 1bß. Specifically, it is being posited that the original 1bß read

in 1bα affected the reading 1bß. Specifically, it is being posited that the original 1bß read ![]() "and the forcefulness of his mouth will be changed." In the original text the

"and the forcefulness of his mouth will be changed." In the original text the ![]() מ was misread as

מ was misread as![]() under the influence of the preceding

under the influence of the preceding ![]() . There is evidence that scribes sometimes wrote two letters so close to each other that confusion arose. For instance, in 11QPsa (Plate 8*, Column X, lines 1 and 6)

. There is evidence that scribes sometimes wrote two letters so close to each other that confusion arose. For instance, in 11QPsa (Plate 8*, Column X, lines 1 and 6) ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() look like

look like ![]() , and

, and ![]() looks like

looks like ![]() .65 The ligature

.65 The ligature  is well attested in the Tanach, and there is considerable evidence of the

is well attested in the Tanach, and there is considerable evidence of the ![]() confusion.66 For instance, one finds in Jos 5:2

confusion.66 For instance, one finds in Jos 5:2 ![]() (Ketib) but

(Ketib) but ![]() (Qere); 2 Kgs 22:4

(Qere); 2 Kgs 22:4![]() but in 2 Chr 34:9

but in 2 Chr 34:9![]() ; Jer 49:19

; Jer 49:19 ![]() but in Jer 50:44

but in Jer 50:44 ![]() (Qere) and

(Qere) and  (Ketib); etcetera. The ligature

(Ketib); etcetera. The ligature

is probably attested in Job 15:27, where

is probably attested in Job 15:27, where would not only be more meaningful but also form a paronomasia with

would not only be more meaningful but also form a paronomasia with  . The form

. The form  occurs in Ps 17:10 and 59:13, and the prefixed form in Ps 58:7. There are numerous cases in the Tanach where the י is missing.

occurs in Ps 17:10 and 59:13, and the prefixed form in Ps 58:7. There are numerous cases in the Tanach where the י is missing.

It is also possible that the word ![]() under the influence of the preceding

under the influence of the preceding ![]() , was spelled

, was spelled ![]() . A similar error might have occurred in Prov 15:14 where

. A similar error might have occurred in Prov 15:14 where ![]() was written under the influence of

was written under the influence of ![]() in Prov 15:13. The Massoretes corrected this error in the Ketib-Qere apparatus, making the Qere

in Prov 15:13. The Massoretes corrected this error in the Ketib-Qere apparatus, making the Qere ![]() instead of the Ketib

instead of the Ketib ![]() 67. Whichever emendation mechanism is adopted 1bß would refer to the tenor of one's speech, akin to

67. Whichever emendation mechanism is adopted 1bß would refer to the tenor of one's speech, akin to  (Ps 68:34), "who thunders forth with his mighty voice." Understanding 1bß as referring to the tenor of one's speech is also supported by Sir 13:26, often cited as a paraphrase of Qoh 8:1. While Sir 13:26a, as 8:bα, states that the visible effect of a good heart is a shining face (

(Ps 68:34), "who thunders forth with his mighty voice." Understanding 1bß as referring to the tenor of one's speech is also supported by Sir 13:26, often cited as a paraphrase of Qoh 8:1. While Sir 13:26a, as 8:bα, states that the visible effect of a good heart is a shining face ( ), Sir 13:26b states that the effect of evil thought is contentious speech (

), Sir 13:26b states that the effect of evil thought is contentious speech (![]() )68).

)68).

Verse 8:2 is critical for the understanding of 8:1, since together with 8:1b it establishes the dominant parallel scheme for the two verses. To develop the dominant parallel scheme, Ginsberg's emendation of  "the face of" in 8:2a is adopted. The single Aramaic word

"the face of" in 8:2a is adopted. The single Aramaic word ![]() , "the face of," corresponds to the Biblical Hebrew

, "the face of," corresponds to the Biblical Hebrew ![]() , from

, from  , which is well attested in the Tanach.69 It is notable that the line

, which is well attested in the Tanach.69 It is notable that the line  occurs in the Elephantine Ahiqar, which surprisingly echoes 8:2a70 It would appear that

occurs in the Elephantine Ahiqar, which surprisingly echoes 8:2a70 It would appear that ![]()

![]() underlies

underlies ![]() in 8:2a. Ginsberg noted that

in 8:2a. Ginsberg noted that

V. 1 and the Elephantine parallel combined suggest very strongly that the first five letters of v. 2, which no ingenuity has yet succeeded in rendering plausibly as they stand, be emended to

'the face of,' and a close examination of the whole of vv. 1-5a renders the emendation practically unavoidable.71

If the interpretation of ![]() as

as ![]() is correct, 8:2a as 8:1bß, will also refer to the "face" or to the expression of the face.72 The second part of 8:2, however, seems to refer to speech, as the term

is correct, 8:2a as 8:1bß, will also refer to the "face" or to the expression of the face.72 The second part of 8:2, however, seems to refer to speech, as the term  "utterance" (Job 5:8) indicates. The specific nature of this "utterance" is not clear. Commentators suggested that this "utterance" related to the "oath of loyalty" (unmen-tioned in the Tanach, cf. 1 Chr 11:3, 29:24),73 "swearing by the name of God" (Exod 22:10),74 and "King's/peoples' oath to God," (2 Kgs 11:17).75 The structural analysis that follows suggests another possibility; that one should be sensitive to a king's change in tenor of speech-to his inclusion of swearing by God. Swearing obviously expresses much emotional involvement and is intended to convey irrational commitment and ultimate credulity.

"utterance" (Job 5:8) indicates. The specific nature of this "utterance" is not clear. Commentators suggested that this "utterance" related to the "oath of loyalty" (unmen-tioned in the Tanach, cf. 1 Chr 11:3, 29:24),73 "swearing by the name of God" (Exod 22:10),74 and "King's/peoples' oath to God," (2 Kgs 11:17).75 The structural analysis that follows suggests another possibility; that one should be sensitive to a king's change in tenor of speech-to his inclusion of swearing by God. Swearing obviously expresses much emotional involvement and is intended to convey irrational commitment and ultimate credulity.

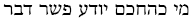

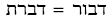

From this discussion emerges the basic structure of the four lines in 8:1-3a. All the lines deal with demeanour, and in each line the first colon relates to facial expression while the second colon refers to manner of speech:

DEMEANOUR

The first column refers to the wise (![]() ), a person (

), a person (![]() ), a king (

), a king (![]() ), and both a wise person and king. Since the first two are also the referents in the corresponding cola of the second column, it is reasonable to assume that that the referent in 8:2b is the king's speech, and 8:3aß refers to both the wise and king; i.e., to a bad argument made by the wise person to the king. In that case, one is advised in 8:2b to watch for a change in the king's tenor of speech indicated by his use of emotionally high-charged language, such as swearing. In 8:3aß one is advised to leave the king's presence when he sees that his words have a bad effect on the king. Since the last three cola in the first column deal with facial expression one would have expected the first colon also to refer to the face. In Modern Hebrew 1bα should have something akin to

), and both a wise person and king. Since the first two are also the referents in the corresponding cola of the second column, it is reasonable to assume that that the referent in 8:2b is the king's speech, and 8:3aß refers to both the wise and king; i.e., to a bad argument made by the wise person to the king. In that case, one is advised in 8:2b to watch for a change in the king's tenor of speech indicated by his use of emotionally high-charged language, such as swearing. In 8:3aß one is advised to leave the king's presence when he sees that his words have a bad effect on the king. Since the last three cola in the first column deal with facial expression one would have expected the first colon also to refer to the face. In Modern Hebrew 1bα should have something akin to![]()

![]() "who is as the wise knows facial expression." Unfortunately, Qohelet did not have the appropriate Hebrew phrase for "facial expression." He left it unsaid, assuming that it would be sensed from the parallel cola.

"who is as the wise knows facial expression." Unfortunately, Qohelet did not have the appropriate Hebrew phrase for "facial expression." He left it unsaid, assuming that it would be sensed from the parallel cola.

The second column refers to manner of speech, which is indicated by use of the root ![]() and the organ of speech (

and the organ of speech (![]() ) in lieu of speech. In the first and last colon the quality of speech is addressed, and in the following two cola the change in tenor is mentioned. In 8:1-3a Qohelet alludes to a range of capabilities that a wise person has regarding demeanour. In particular, a wise man's pleasant facial expression is a basic asset in reducing animosity and promoting rationality and sincerity; he can "read" the facial expressions of others; he is articulate; he can modify the tenor of his speech; he is capable of noticing variation in tenor of speech; and he knows to assess their effect.

) in lieu of speech. In the first and last colon the quality of speech is addressed, and in the following two cola the change in tenor is mentioned. In 8:1-3a Qohelet alludes to a range of capabilities that a wise person has regarding demeanour. In particular, a wise man's pleasant facial expression is a basic asset in reducing animosity and promoting rationality and sincerity; he can "read" the facial expressions of others; he is articulate; he can modify the tenor of his speech; he is capable of noticing variation in tenor of speech; and he knows to assess their effect.

Each of the lines in 8:1-3a can be characterized as follows:

8:1a: General statement about a wise person's capabilities regarding facial expression and articulation, which is formulated as two rhetorical questions;76

8:1b: Wisdom makes a person's face look more pleasant, and it modifies the forcefulness of his speech;

8:2: A wise petitioner should watch a kings facial expression, and he should watch the change in the king's speech, such as use of swearing words;77 and,

8:3a: A wise petitioner should not be disquieted by a change in the king's facial expression. However, seeing that his arguments badly affect the king he should leave.

It is notable that the opposite phrases ![]() in 1bß and

in 1bß and ![]() in 3aß form a thematic inclusio in the unit, which ends with the conclusion in 3b-4.78

in 3aß form a thematic inclusio in the unit, which ends with the conclusion in 3b-4.78

D CONCLUSION

Irwin observes regarding Qoh 8:1-9 that

By common consent we have here a series of more or less disconnected comments perhaps in some way gathered about the general theme of monarchs and despots. There is no agreement, however, on even this modest measure of unity ... But in reality the passage is a well-organized unit treating of a single theme that is developed consistently to its conclusion in verse 9.79

This study is in full agreement with Irwin's position with respect to the sub-unit 8:1-3a. It has been shown in this study that the theme of 8:1-3a is human demeanour in particular one's facial and oral expression. The four lines of 8:1-3a form a clear parallelism, which is anchored on the two keywords: ![]() and

and ![]() 80.

80.

The structure of 8:1-3a, as well as Sir 13:26, imply that 1bß has to refer to speech.81 It has been demonstrated that such a reading is possible, since there is evidence that ![]() could be a corruption of

could be a corruption of ![]() , the organ of speech. The parallelism of

, the organ of speech. The parallelism of![]() and

and ![]() in v. 4 indicates that in the entire section the term

in v. 4 indicates that in the entire section the term ![]() should be understood as "speech, utterance, words."

should be understood as "speech, utterance, words."

Moreover, the structure of 8:1-3a implies that 2b must refer to the king's face as 3a does. It has been demonstrated that such a reading is not only possible, but also elegantly resolves the problem of the awkward ![]() in 2a. The reading

in 2a. The reading ![]() instead of

instead of![]() introduces an Aramaism.82 However, this is not the only Aramaism in the book.

introduces an Aramaism.82 However, this is not the only Aramaism in the book.

Finally, the unit structure implies that the abrupt 1aα must allude to facial expression. Unfortunately Qohelet did not have a proper Hebrew term for "facial expression."83 He left 1aα undefined, assuming the reader would deduce the alluded sense from the concrete examples in 1bα, emended 2a, and 3a.

Difficulties encountered in interpretation of 8:1 forced many commentators to use extraneous notions for imbuing this verse with definiteness and internal coherence. Recognition of the underlying structure of 8:1-3a, and similarities with Sir 13:26 and Elephantine Ahiqar, point to some minor scribal errors. Correction of these errors restores the contextual sense of the verse. The proposed interpretation of 8:1 and understanding of 8:1-3a suggests that the population of Yehud had considerable access to higher officialdom during the Ptolemaic period, making the advice given rather useful.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Artom, Elia S. (..)Tel-Aviv: Yavneh, 1959. [ Links ]

Baltzer, Klaus R. "Women and War in Qohelet 7:23-8:1a." Harvard Theological Review 80 (1987): 127-32. [ Links ]

Barton, George A. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Ecclesiastes. International Critical Commentary. Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1908. [ Links ]

Beentjes, Panc C. "'Who Is Like the Wise?': Some Notes on Qohelet 8,1-15." Pages 303-315 in Qohelet in the Context of Wisdom. Edited by Anton Schoors. Bibliotheca Ephemeridum Theologicarum Lovaniensium 136. Leuven: Leuven University Press, 1998. [ Links ]

Brown, Francis, Samuel R. Driver, and Charles A. Briggs. A Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1907. [ Links ]

Cowley, Arthur E. Aramaic Papyri in the Fifth Century B.C. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1923. [ Links ]

Crenshaw, James L. Ecclesiastes. Westminster: John Knox Press, 1987. [ Links ]

Dahood, Mitchell J. "Canaanite-Phoenician Influence in Qoheleth." Biblica 33 (1952): 30-52. [ Links ]

______. "Qoheleth and Recent Discoveries." Biblica 39 (1958): 302-318. [ Links ]

Delitzsch, Franz. Hoheslied und Koheleth. Biblischer Kommentar, Altes Testament 4. Leipzig: Dorffling & Franke, 1875. [ Links ]

Elliger, Karl and Wilhelm Rudolph. Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia. Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 1983. [ Links ]

Elster, Ernst. Prediger Salamo. Göttingen: Verlag der Dieterichschen Buchhandlung, 1855. [ Links ]

Botterweck, G. Johannes and Helmer Ringgren, eds. Theologisches Wörterbuch zum Alten Testament. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer Verlag, 1970-2000. [ Links ]

Fox, Michael V. A Time to Tear Down and A Time to Build Up. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1999. [ Links ]

Fox, Michael V. and Bezalel Porten. "Unsought Discoveries: Qohelet 7:23-8:1a." Hebrew Studies 19 (1978): 26-38. [ Links ]

Friedlander, David and Stan Franklin. "LIDA and a Theory of Mind." Pages 137-148 in Artificial General Intelligence 2008. Edited by Pei Wang, Ben Goertzel, Stan Franklin. Amsterdam: IOS Press, 2008. [ Links ]

Galling, Kurt. "Der Prediger." Die fünf Megilloth. 2nd edition. Edited by Max Haller. Handbuch zum Alten Testament 1, 18; Tübingen: Mohr/Siebeck, 1969. [ Links ]

Ginsberg, H. Louis. Studies in Koheleth. New York: Jewish Theological Seminary of America, 1952. [ Links ]

Ginsburg, Christian D. Coheleth. London: Longman, 1861. [ Links ]

Gordis, Robert. Koheleth, the Man and his World: A Study of Ecclesiastes. 3rd edition. New York: Schocken, 1968. [ Links ]

Graetz, Heinrich. Kohelet. Leipzig: C.F. Winter'sche Verlagshandlung, 1871. [ Links ]

Hengstenberg, Ernst W. Commentary on Ecclesiastes. Philadelphia: Smith, English & Co., 1869. [ Links ]

Hertzberg, Hans W. Der Prediger. Kommentar zum Alten Testament n.s. 17, 4. Gutersloh: Mohn, 1963. [ Links ]

Hitzig, Ferdinand and Wilhelm Nowack. Der Prediger Salomos. 2nd ed. Kurzgefasstes exegetisches Handbuch zum Alten Testament 7. Leipzig: Hirzel, 1883. [ Links ]

Irwin, William A. "Ecclesiastes 8:2-9." Journal of Near Eastern Studies 4 (1945): 130-31. [ Links ]

Jastrow, Marcus A. Jr. A Gentle Cynic, Being a Translation of the Book of Koheleth. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1919. [ Links ]

Jones, Scott C. "Qohelet's Courtly Wisdom: Ecclesiastes 8:1-9." Catholic Biblical Quarterly 68/2 (2006): 211-228 [ Links ]

Kiel, Yehudah. (..). Jerusalem: Mosad HaRav Kook, 1981. [ Links ]

Klein, Christian. Kohelet und die Weisheit Israels: Eine formgeschichtleche Studie. [ Links ]

Beiträge zur Wissenschaft vom Alten und Neuen Testament 132. Stuttgart: W. Kohlhammer, 1994. [ Links ]

Knobel, August. Commentar über das Buch Koheleth. Leipzig: Verlag von Johann Ambrosius Barth, 1836. [ Links ]

Krüger, Thomas. "Meaningful Ambiguities in the Book of Qoheleth." Pages 63-74 in The Language of Qohelet in Its Context: Essays in Honour of Prof. A. Schoors on the Occasion of his Seventieth Birthday. Edited by Angelika Berlejung and Pierre van Hecke. Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 164. Leuven: Peeters, 2007. [ Links ]

Lauha, Aare. Kohelet. Biblischer Kommentar, Altes Testament 19. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchen Verlag, 1978. [ Links ]

Loader, James A. Polar Structures in the Book of Qohelet. Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 152. Berlin: de Gruyter, 1979. [ Links ]

Lohfink, Norbert. Kohelet. Neue Echter Bibel. Wurzburg: Echter Verlag, 1980. [ Links ]

Longman, Tremper. The Book of Ecclesiastes. New International Commentary on the Old Testament. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998. [ Links ]

Loretz, Oswald. Qohelet und der Alte Orient: Untersuchungen zu Stil und theologischer Thematik des Buches Qohelet. Freiburg: Basel, 1964. [ Links ]

______. "'Frau' und griechisch-jüdische Philosophie im Buch Qohelet (Qoh 7,23-8,1 und 9,6-10)." Ugarit-Forschungen 23 (1991): 245-64. [ Links ]

McCarter, P. Kyle Jr. I Samuel. Anchor Bible 8. Garden City: Doubleday, 1980. [ Links ]

Michel, Diethelm. "Qohelet-Probleme: Uberlegungen zu Qoh 8,2-9 und 7,11-14." Theologia Viatorum 15 (1979/80): 81-103. [ Links ]

Murphy, Roland E. Ecclesiastes. Word Biblical Commentary. Dallas: Word Inc., 1992. [ Links ]

Perry, T. Anthony. Dialogues with Kohelet: The Book of Ecclesiastes. University Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993. [ Links ]

Pinker, Aron. "Qohelet's Views on Women-Misogyny or Standard Perceptions? An Analysis of Qohelet 7:23-29 and 9:9." Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament 26/2 (2012): 157-191. [ Links ]

Plumptre, Edward H. Ecclesiastes: or, the Preacher. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1881. [ Links ]

Publius Ovidius Naso. Epistulae ex Ponto II. Starting 9 C.E. [ Links ]

Rendsburg, Gary A. "The Northern Origin of the 'Last Words of David' (2 Sam 23,1-7)." Biblica 69/1 (1988): 113-121. [ Links ]

Schwienhorst-Schönberger, Ludger. Kohelet. Herders theologischer Kommentar zum Alten Testament. Freiburg: Herder, 2004. [ Links ]

Seow, Choon-Leong. Ecclesiastes: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. New York: Yale University, 2008. [ Links ]

Siegfried, D. Carl. Prediger und Hocheslied. Handbuch zum Alten Testament 2, 3/2. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1898. [ Links ]

Stuart, Moses. Commentary on Ecclesiastes. New York: G.P. Putnam, 1851. [ Links ]

Tov, Emanuel. The Textual Criticism of the Bible, An Introduction. Jerusalem: Mosad Bialik, 1990. [ Links ]

Tur-Sinai, Naphtali H. הספר. Volume 2 of הלשון והפר. Jerusalem: Mosad Bialik, 1959. Waldman, Nahum. "The dābār ra' of Eccl 8:3." Journal of Biblical Literature 98 (1979): 407-408.

Weiss, R. "On Ligatures in the Hebrew Bible (ם=נו)." Journal of Biblical Literature 82 (1963): 188-194. [ Links ]

Whitley, Charles. F. Koheleth: His Language and Thought. Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 148. Berlin: de Gruyter, 1979. [ Links ]

Whybray, Roger N. Ecclesiastes. Old Testament Guides. Sheffield: JSOT Press 1989. [ Links ]

Wildeboer, D. Gerrit "Der Prediger." Pages 109-168 in Die fünf Megillot. Edited by Karl Bude, Alfred Bertholet and D. Gerrit Wildeboer. Kurzer Hand-Commentar Zum Alten Testament 17. Freiburg: Mohr, 1898. [ Links ]

Wright, Charles H.H. The Book of Koheleth. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1888. [ Links ]

Zapletal, Vincenz. Das Buch Kohelet. Freiburg: O. Gschwend, 1911. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Aron Pinker

11519 Monticello Ave, Silver Spring

Maryland, 20902, USA

Email: aron_pinker@hotmail.com

1Heinrich Graetz, Kohelet (Leipzig: C.F. Winter'sche Verlagshandlung, 1871), 100.

2 Michael V. Fox, A Time to Tear Down and A Time to Build Up (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1999), 276.

3 Moses Stuart, Commentary on Ecclesiastes (New York: G.P. Putnam, 1851), 230.

4 Ernst Elster, Prediger Salamo (Göttingen: Verlag der Dieterichschen Buchhandlung, 1855), 102; Ferdinand Hitzig and Wilhelm Nowack, Der Prediger Salomos (2nd ed. KEHAT 7; Leipzig: Hirzel, 1883), 267; Stuart, Commentary, 230; New Jewish Publication Society; James L. Crenshaw, Ecclesiastes (Westminster: John Knox Press, 1987), 149; etc..

5 Hitzig and Nowack, Prediger, 267.

6 Charles H. H. Wright, The Book of Koheleth (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1888), 395.

7 For instance, the following think that 8:1 alludes to the preceding material: Stuart, Commentary, 230; Hans W. Hertzberg, Der Prediger (KAT n.s., 17, 4; Gütersloh: Mohn, 1963), 156-163; Kurt Galling, "Der Prediger," in Die fünf Megilloth (2nd ed.; ed. Max Haller; HAT 18; Tübingen: Mohr/Siebeck, 1969), 108-110; Norbert Lohfink, Kohelet (NEchtB; Wurzburg: Echter Verlag, 1980), 56-59; Aare Lauha, Kohelet (BKAT 19; Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchen Verlag, 1978), 146; Diethelm Michel, "Qohelet-Probleme: Überlegungen zu Qoh 8,2-9 und 7,11-14," ThViat 15 (1979/80): 81-103; Roger N. Whybray, Ecclesiastes (OTG; Sheffield: JSOT Press, 1989), 128; James A. Loader, Polar Structures in the Book of Qohelet (BZAW 152; Berlin: de Gruyter, 1979), 50-54; Tremper Longman, The Book of Ecclesiastes (NICOT; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998), 209; Klaus R. Baltzer, "Women and War in Qohelet 7:23-8:1a," HTR 80 (1987): 127-32; Oswald Loretz, "'Frau' und griechisch-jüdische Philosophie im Buch Qohelet (Qoh 7,23-8,1 und 9,6-10)," UF 23 (1991): 245-64; Michael V. Fox, and Bezalel Porten, "Unsought Discoveries: Qohelet 7:23-8:1a," HS 19 (1978): 26-38; etc.

8 Choon-Leong Seow, Ecclesiastes: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (New York: Yale University, 2008), 290.

9 Aron Pinker, "Qohelet's Views on Women-Misogyny or Standard Perceptions? An Analysis of Qohelet 7:23-29 and 9:9," SJOT 26/2 (2012): 157-191.

10 George A. Barton, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Ecclesi-astes (ICC; Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1908), 149. Cf. also Lauha, Kohelet, 144.

11 Franz Delitzsch, Hoheslied und Koheleth (BKAT 4; Leipzig: Dorffling & Franke, 1875), 331.

12 Many consider 8:1 the beginning of a new unit. See, for instance, Ernst W. Hengstenberg, Commentary on Ecclesiastes (Philadelphia: Smith, English & Co., 1869), 191; Delitzsch, Hoheslied, 330; August Knobel, Commentar über das Buch Koheleth (Leipzig: Verlag von Johann Ambrosius Barth, 1836), 269; Seow, Ecclesiastes, 290; etc.

13 Seow, Ecclesiastes, 290.

14 Charles. F. Whitley, Koheleth: His Language and Thought (BZAW 148; Berlin: de Gruyter, 1979), 71. Whitley notes that in Egyptian Aramaic הפשר occurs with the meaning "to settle an account."

15 Crenshaw, Ecclesiastes, 150.

16 This reading has been adopted by the Vulgate, as well as a number of modern commentators. Seow, Ecclesiastes, 277; H. Louis, Ginsberg, Studies in Koheleth (New York: Jewish Theological Seminary of America, 1952), 35; etc..

17 There was apparently a tradition for such reading, as indicated in the passage: "Rabbah bar Rab Huna says, with respect to every man who has impudence of expression it is lawful to call him wicked, for it is written (Prov 21:29) 'a wicked man hardens his face.' Rab Nachman bar Isaac says, it is lawful to hate him, for it is written (Qoh 8:1) 'and the coarseness of his face is changed.' Read not changed (ישנא) but hated (ישנא) (bTa'anit, 7b). This reading has been adopted by Graetz, Kohelet, 101; D. Carl Siegfried, Prediger und Hocheslied (HAT II, 3/2; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1898), 62; etc..

18 Compare 2 Kgs 25:29 with Jer 52:33. /הא confusion occurs often in the Tanach. See for instance, Lam 4:1 ישנא for ישנה Gen 42:43 אברך for הברך; איך[Gen 26:9] but היך [Dan 10:17]; Lev 24:7 לאזברה for להזברה; Ruth 1:20 מרא for מרה; 1 Kgs 22:25, 2 Kgs 7:12 הבחלה but אבחלה in 2 Chr 18:24; Job 8:21 ימלה for מראי; Isa 44:8 חרהו for חראו; Ezek 14:4 הב (K) but אב (Q); 2 Chr 20:35 אחחבר for התחבר; Ezek 14:3 האדרש for ההדרש; Jer 25:3 אשבים for השבים; Ps 76:6 אשזללו for השחוללו; Isa 63:3 אגאלתי for הגאלתי; Jer 52:15 האמון for ההמון; Hos 12:9 און for אדרם ;הון in 2 Sam 20:24 and 1 Kgs 12:18 but הדרם in 2 Chr 10:18; נאק in Ezek 30:24 but נהק in Job 6:5; צנא Num 32:24 but צנה Ps 8:8; דבה (Deut 23:2) but דכא in some MSS (Tanach Koren [1983] 11 end); Dan 11:44 according to the Massorah, in the Land of Israel the reading was חמה and in Babylon חמא; etc..

19 This reading has been adopted by a number of modern commentators. Cf. for instance, Barton, Ecclesiastes, 151; Siegfried, Prediger, 62; BDB 739a; etc..

20 Robert Gordis, Koheleth, the Man and his World: A Study of Ecclesiastes (3rd ed.; New York: Schocken, 1968), 286.

21 For instance אל בקצפך אל תוביחני (Ps 38:2); יחי ראובן ואל ימת ראובן (Deut 33:6); מתן בסתר יבפה אך ושחד בחק יבפה חמה ץזה (Prov 21:14); מאל אביך ויץזרך ומאח שדי (Gen 49:25); מישרים אהבוך ץלמות (Song 1:4); etc..

22 The reading ביודץ is also adopted by Knobel, Buch Koheleth, 269.

23 Christian D. Ginsburg, Coheleth (London: Longman, 1861), 390. Ginsburg says, "The phrase פשר דבר exactly corresponds to the Hebrew נבון דבר in 1 Sam 16:18." This does not seem to be the case. In 1 Sam 16:18 דבר is apparently referring to speech.

24 Ginsburg, Coheleth, 391.

25 Hengstenberg, Commentary, 191. Hengstenberg takes דבר = מה שהיה in 7:24 and designating the object of wisdom, but does not provide any justification.

26 Hengstenberg, Commentary, 192.

27 Delitzsch, Hoheslied, 331.

28 Edward H. Plumptre, Ecclesiastes: or, the Preacher (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1881), 174.

29 Publius Ovidius Naso (43 b.c.e. - 14 c.e.), Epistulae ex Ponto II (starting 9 c.e.), 9.47.

30 Stuart, Commentary, 230. Stuart (231) believes that on a deeper level Qohelet is saying: "Wisdom preserves life, or imparts the light of life, while haughtiness brings on the disfigurement of death." The questions in 1a are Qohelet's uncertain sentiments on whether this deep thought would be understood by the reader. Indeed, there is much room to doubt!

31 D. Gerrit Wildeboer, "Der Prediger," in Die fünf Megillot (Freiburg: Mohr, 1898), 149.

32 Graetz, Kohelet, 100. Graetz understands 1bß as meaning: "der Trotzige (der sich geradezu dem Könige widersetzt, wie die Verschworenen gegen Herodos) wird verhasst."

33 Gordis, Koheleth, 286.

34 Gordis, Koheleth, 287.

35 Crenshaw, Ecclesiastes, 149.

36 Crenshaw, Ecclesiastes, 149.

37 Fox, Time to Tear Down, 276.

38 Seow, Ecclesiastes, 291.

39 Ginsberg, Studies, 35. Ginsberg says: "חבמת is to be assumed to be original in the Hebrew, but to reflect there a חבמת which (under the influence of חבים in the first half of the verse) had supplanted the correct חדות in the Aramaic original from which the Hebrew was made."

40 Attempts to see in these expressions support for linking 8:1 to the preceding section cannot be justified.

41 Note also Qoh 6:10 שהתקיף (Ketib) but שתקיף (Qere); Qoh 10:3 בשהםבל (K) but כשסכל (Q); and, 2 Kgs 7:12 בהשדה (K) but בשדה (Q). It has been suggested that the non-syncope of the ה is indicative of a Northern provenance. Cf. Gary A. Rendsburg, "The Northern Origin of the 'Last Words of David' (2 Sam 23,1-7)," Bib 69/1 (1988): 116.

42 Seow, Ecclesiastes, 277, says: "As Euringer has argued, tis oiden sophous 'who knows the wise' in LXX may be the result of an inner Greek corruption from tis hade sophos 'who is so wise' (as in Aq; cf. tis houtos sophos in Symm; also SyrH, OL), an error prompted in part by the next rhetorical question: kai tis oiden lysin rhematos 'who knows the solution of a saying' (see Euringer, Masorahtext, pp. 93-94)."

43 Vincenz Zapletal, Das Buch Kohelet (Freiburg: O. Gschwend, 1911), 189.

44 Scott C. Jones, "Qohelet's Courtly Wisdom: Ecclesiastes 8:1-9," CBQ 68/2 (2006): 211-228. Jones suggests that in 8:1a: פשר דבר refers to the prognostication of a divine oracle, and it belongs, as it does elsewhere in the Hebrew Bible, in the context of mantic wisdom in the royal court."

45 H.-J. Fabry and U. Dahmen, פשר ThWAT 6: 810-816.

46 The feminine form פשרה occurs in Sir 38:14, where it parallels רפאות and may mean "judgment," as the Samaritan פשרונה (Exod 21:1 and frequently).

47 The MT idiom ץז פניו is unique, but supported by a number of Hebrew MSS that have ץוז, with the mater clearly indicating a noun. Seow, Ecclesiastes, 278-79, argues that "the unique expression ץז פנים is to be preferred, since it is likely that the other reading merely conforms to the more common idiom."

48 Delitzsch, Hoheslied, 331. Cf. b. Ber. 16b; b. Šabb. 30b; b. Besah 25b; and b. 'Abot 5:20.

49 Ginsburg, Coheleth, 391.

50 Gordis, Koheleth, 286-287. Cf. 7:1, יום הולדו, "the day of one's birth," and Gordis' note there.

51 Cf. Sir 9:18, 12:18, and 13:25.

52 Vulgate; Hitzig and Nowack, Prediger, 268; Zapletal, Kohelet, 190; BHS; Galling, Prediger, 108-110; Ginsberg, Studies in Koheleth, 35; etc.