Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Agricultural Extension

versão On-line ISSN 2413-3221

versão impressa ISSN 0301-603X

S Afr. Jnl. Agric. Ext. vol.51 no.4 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2413-3221/2023/v51n4a12530

ARTICLES

The Operational Elements of the Vegetable Cooperatives: The Case of Agricultural Cooperative Societies in King Sabata Dalindyebo Local Municipality, Eastern Cape Province

Sohuma A.I; Yusuf S.F.G.II; Popoola O.O.III

IMaster of Agriculture Student: Agricultural Extension and Rural Development, Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension. University of Fort Hare, Alice Campus, Email: 201200490@ufh.ac.za, Orcid 00000001-6260-6428

IISenior Lecturer: Agricultural Extension and Rural Development, Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension. University of Fort Hare, Alice Campus, 1 King Williams Town Road Private Bag X1314 Alice 5700. Tel. +27 (40) 602 2127; E mail: fyusuf@ufh.ac.za, Orcid 0000-0002-4156-1221

IIIPost-doctoral Fellow: Agricultural Extension and Rural Development, Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension. University of Fort Hare, Alice Campus, 1 King Williams Town Road Private Bag X1314 Alice 5700. E mail: opopoola@ufh.ac.za, Orcid 0000-0002-8514-5713

ABSTRACT

Cooperatives are typically established to help create jobs and improve their members' economic and social conditions, among various other roles. Farmers ' cooperative societies play a vital role in enhancing the livelihood of resource-poor farmers. The government has initiated various support programmes to assist agricultural cooperative societies to remain viable; however, many cooperatives continue to flounder while some have collapsed. This study identifies operational components like members' roles, cooperative constitutions and decision-making processes, record-keeping, education and training of members, farm and financial management and level of extension service involvement as critical roles in sustaining agricultural cooperatives. Therefore, this study's objective was to assess the key operational components of vegetable cooperative societies and the level of extension support provided to the cooperatives in the study area. Ten functional vegetable cooperatives in the municipality were purposively selected for the study. At the same time, data for the survey was obtained from the board of directors and members of the cooperatives. Data was collected using semi-structured questionnaires consisting of closed and open-ended questions. The presentation of results was done using simple descriptive statistical tools. The study outcome shows that about 50% of the cooperatives noted that members were largely involved in the daily running of the cooperatives, governance, and decision-making processes. However, many cooperatives are constrained by the lack of training of its members on conflict resolutions (90%), with about 30% and 40% not receiving training on record keeping and financial management, respectively. The role of extension services towards the sustainability of the cooperatives is crucial. Most (80%) of the cooperatives indicated some level of interaction between the cooperatives and extension personnel, albeit the need to improve the frequency of extension visits, training, and follow-up appointments. The result of this study implies that cooperatives in the region need to improve in key operational areas. Extension personnel need to be more available to support cooperative activities effectively.

Keywords: Farm Management, Record Keeping, Training, Constitution, Decision Making, Extension

1. INTRODUCTION

Cooperatives are generally founded to enhance the socio-economic status of its members. They contribute significantly to food security, create job opportunities, and stimulate social and economic empowerment (Abebaw & Haile, 2013; Abate, Francesconi & Getnet, 2014; Herbel, Rocchigiani & Ferrier, 2015; Chepkwei, Wanyoike & Koima, 2017). Certain basic principles primarily guide cooperatives. These principles include voluntary and open membership, democratic governance, equal economic participation of members, autonomy and independence, facilitation of education, training and information delivery services to members and concern for the community (Thaba & Mbohwa, 2015). The Cooperative Act (14/2005) regulates all cooperative operations in South Africa. It aims to support the principles of self-assistance, self-accountability, independence, social equality and social obligation for all cooperatives (Ortmann & King, 2007). These cooperatives include marketing and supply, worker, financial, consumer, housing, and agricultural cooperatives (Department of Trade and Industry [DTI], 2012). Agricultural cooperatives "produces, process or market agricultural products and supplies agricultural inputs and services to its members" (Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries [DAFF], 2010: 3). Cooperatives are maintained by the state through financial and non-financial inputs such as seeds, machinery and fertilisers among other inputs. Input supply, shared product marketing and agricultural products processing cooperatives are a few significant examples of agricultural cooperative initiatives in South Africa (Thaba, Anim & Tshikororo, 2017). The Farm-together cooperative training program, established to provide agricultural cooperative members with technical skills, mentorship, record keeping, access to markets and general management workshops across the nation, is another notable cooperative project (DAFF, 2017).

Farmer's cooperative societies play a vital role in enhancing the livelihoods of resource-poor farmers (Eastern Cape Planning Commission [ECPC], 2014). These cooperatives provide facilities to its members at reasonable costs and assist in generating sustainable livelihoods (ECPC, 2014). Given the critical role that agricultural cooperatives play in society, the government, especially in developing countries, are committed to promoting cooperatives to become efficient, profitable and sustainable. In South Africa, the government has invested heavily to support newly established agricultural cooperatives; in addition, financial investments have been made by many other institutions to support agricultural cooperative development in the country (DAFF, 2015). These efforts are made to promote sustainable cooperatives that can address unemployment challenges, promote equality and alleviate poverty. The provision of extension services is another major support structure the government put in place to aid the region's agricultural cooperatives. Extension support encompasses input supply, facilitating workshop and training programmes, conflict resolution and provision of advisory services on business and financial planning, resource management, use of contemporary agricultural technologies and general farm management (Mzuyanda, 2014; Mabaleka, 2014; Levy, 2017; Kyazze, Nkote & Wakaisuka-Isingoma, 2017; Mabunda, 2017). Despite these levels of support, many cooperatives continue to flounder while some have entirely liquidated. The failure or collapse of these cooperatives could be influenced by multiple factors, which could be economic, social, environmental or institutional. A key related aspect is the operational activities of these cooperatives, which could, indeed, make or mar the sustainability of cooperatives.

Cooperatives are expected to function in an efficient capacity that would allow for their longterm sustenance. The expected operational conduct of cooperatives, as outlined in the cooperative principles, was highlighted in Thaba and Mbohwa's (2015) study. Some of these include democratic governance, equal participatory opportunities for members and their access to education and training. Therefore, this study identifies components comprising members' roles and positions, cooperative constitutions and decision-making processes, record-keeping, education and training of members, farm and financial management, and level of extension service involvement as playing critical roles in sustaining agricultural cooperatives. The active participation of cooperative members and their competency in corporate management, marketing, and bookkeeping contribute to organisational sustainability (Chibanda, Ortmann & Lyne, 2009). This study aimed to assess the key operational components of vegetable cooperative societies and the level of extension support provided to King Sabata Dalindyebo Local Municipality (KSDLM) cooperatives.

2. METHODOLOGY

KSDLM is a Category B local municipality situated within the O.R. Tambo District Municipality in the province of the Eastern Cape with an area of 3 027km2; coordinates of 31.7074° S, 28.5798° E; it is the largest of the five local municipalities in the district (KSD, Integrated Development Plan [IDP], 2014).

2.1. Site Description

The identified cooperatives are dispersed across Mthatha town in King Sabata Dalindyebo local municipality under O.R Tambo District. The study was conducted in the following villages: Mbuqe Extension, Ncambedlana, Ncise, Mabheleni, Mateko, Lwandlane and Lwalweni. The cooperatives have mixed farming practices but are more focused on vegetables. The cooperatives use water from the nearest rivers and boreholes for irrigation. The seedlings from the nursery and vegetables are sold in the villages, surrounding areas, schools, hawkers and retailers in the nearest towns. The cooperatives would like to see their farming business market expand. Six cooperative societies wanted anonymity; therefore, the study used coding to protect the participants' identities (refer to Table 1). The identified cooperatives in the study area had 63 members, with memberships ranging from 5 to 10.

The list of registered vegetable cooperatives in the municipality was obtained from extension officers assigned to the study area. At the time of this study's survey, the field officers identified 10 of the vegetable cooperatives as fully operational and purposively selected. The research occurred when cooperative numbers one and seven had ten members each; cooperative numbers two, three, four, five, six and 10 had five members each; cooperative number eight had six members; and cooperative number nine had seven members. The total number of cooperative members is 63, while each cooperative society has three (3) to four (4) members that constitute the board of directors (BoDs). Apart from the members of the 10 cooperative societies (n=63), 10 BoD members were interviewed, representing one BoD per cooperative. The BoD interviewed was either the chairperson or the secretary. Data was obtained using semi-structured questionnaires consisting of open and closed-ended questions. Depending on how well-versed the cooperative members were in each language, isiXhosa and English were used to collect the data. Face validity assessment of the instrument's contents, the extent to which it relates to the concepts being measured, was carried out. A reliability test was also carried out. The questionnaires were pre-tested at Raymond Mhlaba Municipality. The internal consistency for reliability was tested for different sections of the questionnaire. The tests with Cronbach's alpha reliability coefficient derived for the items from different sections suggested that all items should be retained. The values achieved for each section were a= 0.82, a= 0.71, and a= 0.76. The derived scores for the pre-test of this study's instrument indicated that it was fit enough to be used as an instrument for the main data collection. Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24 was used for data analysis, while results were presented using simple descriptive statistical tools (frequency and percentage).

3. RESULTS

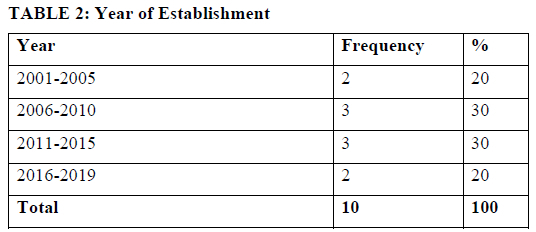

3.1. Year of Cooperative Establishment

The results indicate that 20% of cooperatives were founded between 2001-2005 and 30% between 2006-2010. More cooperatives (30% and 20%) were established between 2011-2015 and 2016-2019, respectively (Table 2).

3.2. Key Operational Components of Vegetable Cooperative Societies in KSDLM

3.2.1. Managerial Positions of Cooperatives

The majority (80%) of cooperatives have never hired an expert outside the purview of the cooperatives to manage their activities, while 10% were hiring in planting seasons, and 10% had a permanent hired manager. The results further indicated that 40% of cooperatives used individual skills as an approach to assign managerial duties, while 30% used teamwork as an approach to assign the responsibilities of management. Other cooperatives (20%) used other approaches like family members to assign management duties, while 10% assigned cooperative management based on the members available daily. In some cooperatives, managerial positions are mostly (50%) delegated to members who alternatively take routines to manage the daily activities of the cooperative. 30% appointed the chairperson to run the managerial duties, while 20% of cooperatives hired professional managers (Table 3).

3.2.2. Cooperative Constitutions and Decision Making

A higher percentage (70%) of the cooperatives in KSDLM have written constitutions governing their cooperative activities, which their cooperative members have formally accepted. In comparison, other cooperatives rely on informal written constitutions agreed upon by all members (10%) or verbal agreements (20%). The majority (90%) indicated that cooperative members adhere to the set constitution, while 10% do not adhere. Decision-making is mainly carried out through a voting process by all members at cooperative meetings (50%). In comparison, other cooperatives leave the decision-making to their chairperson (30%) or board of directors (10%) and other decision-making approaches (10%) (Table 4).

3.2.3. Record Keeping

Analysis of record keeping of cooperative business transactions revealed that all the 10 cooperatives kept some form of basic documentation such as operational, sales, financial and the minutes of General Meetings. While the majority (70%) indicated that their record books were up to date, about 30% implied otherwise; about 30% of the cooperatives noted that members had daily access to the records, while 40% denoted that members only had monthly access to the records. Some members revealed to have access to records weekly (10%), quarterly (10%) and otherwise (10%). On factors restricting the consistency of keeping records, 70% of cooperatives had no underlying factors, 10% identified a lack of sufficient training in members, 10% mentioned that the problem is due to one person handling all the paperwork, and 10% stated otherwise (Table 5).

Further analysis showed that the majority (50%) of the cooperatives delegated record-keeping duties to their cooperative secretaries, while 20% indicated that record-keeping tasks are delegated to general members. Other cooperatives delegated a chairperson (10%), manager (10%) or otherwise (10%) to keep records. Most (70%) cooperatives indicated that the individuals assigned such duties have had some level of training on record keeping, while 30% had never received training on record keeping. However, the frequency of training is below par (Table 6).

3.2.4. Financial Management and Training

A number (80%) of the cooperatives have functional bank accounts. In comparison, others (20%) had no bank account under their cooperative name and opted to keep money in a safe (10%) and member's accounts (10%). Cooperatives (70%) indicated that money is deposited into the cooperative accounts daily, while 20% deposit weekly and 10% deposit monthly.

Several cooperatives also mentioned having savings for emergency purposes, which are kept in a safe (20%), cooperative bank account (30%), personal bank account (30%) and others (20%) had no savings at all (Table 7).

A higher percentage (60%) claimed that cooperative members had been trained in financial management, while 40% never had training. However, about 40% maintained that the training was done only once since the cooperatives were established; others (10%) said it happens once, maybe in a year, and once in three years (10%) (Table 8).

3.2.5. Internal Conflicts, Arbitrators and Conflict Management

Results revealed that 70% of the cooperatives rarely have incidences of internal conflicts as members mostly agree to differ. In comparison, 10% admit encountering internal conflicts daily, 10% never experience any internal conflict, and 10% are unsure. About 60% indicated that the cooperative chairpersons usually act as arbitrators when conflict arises, while 20% rely on the board of directors and 10% on professionals for conflict resolution. Findings on conflict management training showed that most (90%) of cooperatives have not had training on conflict management. In comparison, 10% received training and the cooperative was trained once since its establishment (Table 9).

3.3. Level of Extension Support Provided to the Cooperatives

The majority (80%) of cooperatives indicated some form of interaction between cooperatives and extension field officers, while 20% did not interact with extension officers. The frequency of interactions is mostly monthly (30%), quarterly at 20%, yearly (20%) and weekly (10%). However, a higher percentage (50%) of the cooperatives claimed that the extension officers only visit them to provide some form of advisory services but have never organised special training programmes on vegetable production for cooperative members. In comparison, 30% argue to receive training when it becomes available with extension officers, 10% trained monthly and 10% trained yearly (Table 10).

4. DISCUSSION

The findings of this study show that 80% of the cooperatives were established between 2001 and 2015 (Table 1). The prolonged existence of cooperatives is by no means dependent on their period of establishment, as many respondents expressed that there were periods when their cooperatives fell on hard times and were almost forced into liquidation. The number of registered cooperatives has escalated in recent years; however, studies (Ortmann & King, 2006; Verhofstadt & Maertens, 2015) have stressed how equivocal it is to determine the extent of the vibrancy of many of the cooperatives. In assessing the critical operational components of the cooperatives, this study revealed that the majority (80%) of cooperatives have never hired an expert outside the purview of the cooperatives to manage their activities and managerial positions are mostly delegated to their chairpersons or other cooperative members (Table 2). This finding agrees with Rebelo, Leal and Teixeira's (2017) observation that rather than recruiting managers, a cooperative's board of directors usually act in a managerial capacity and executes management roles. A manager's role in cooperatives primarily oversees the society's daily activities (Kurjanska, 2015). According to DAFF (2014), the board of directors must hire managers with proper competencies to reveal and highlight cooperative values and principles. However, cooperatives may lack the capacity to hire competent managers due to the poor salary scale for managers (DAFF, 2015). In addition, the majority of the cooperatives preference to rely on members to run their activities indicates Herbel et al.'s (2015) view that many farmers may become preeminent directors of their cooperatives if provided with the opportunity. Running the cooperative allows farmers to show and grow their potential, boost their entrepreneurial aptitude, self-esteem and respect, and give room for social acknowledgement by their peers (Herbel et al., 2015). Notwithstanding, many cooperatives are faced with the challenges of having competent leaders with the appropriate management skills and experience (Keshelashvili, 2017), which could, in the long run, be a contributory factor to the collapse of many cooperatives.

Further findings showed that a higher percentage (70%) of the cooperatives operate under the terms of a formal written constitution. In contrast, others rely on informal written constitutions or verbal agreements (Table 3). Twalo (2012) stressed that cooperatives must operate under the constitutions aligned with the Cooperative Act No.14 of 2005, which categorically states that every cooperative should set rules for their functioning, operations, capital and ownership. For most cooperatives, decision-making is mostly carried out through a voting process by all members at cooperative meetings; others leave the decision-making to their chairpersons or board of directors (Table 3). This implies that most cooperatives understand and abide by the Cooperative Act No.14 of 2005. Rebelo et al. (2017) noted that the decision-making process in cooperatives is controlled through the democratic principle of one member being entitled to one vote, as clearly stated in the Cooperative Act No.14 of 2005. However, the board of directors may decide to leave the decision-making in the hands of their managers (Rebelo et al., 2017). Analysis of record keeping of cooperative business transactions revealed that all the cooperatives kept some form of basic documentation such as operational, sales, financial and the minutes of general meetings. Record keeping for any organisation is crucial. Musah and Ibrahim (2014) posit that organisational records fortify their accountability and provide a backup memory for organisations. For instance, Chebet and Kennedy (2019) stressed the need for cooperatives to fully comply with all procedures regarding keeping records of their finances as it would aid the cooperatives' cash tracking system and financial sustainability. About 30% of the cooperatives indicated that members had daily access to the records, while 40% denoted those members only had access to the records monthly (Table 4). The Cooperative Act No.14 of 2005 emphasises the importance of record-keeping which should be made available at the cooperatives' registered office and accessible at all times for auditing purposes (DAFF, 2010).

Most (80%) of the cooperatives have functional bank accounts, with about 70% depositing money into the cooperative accounts daily (Table 6). According to Chebet and Kennedy (2019), an organisation's efficiency and longevity depend very well on its financial sustainability and ability to manage cash effectively. Savings are crucial for cooperative societies to allow for accountability. This is also a key mandate in the Cooperative Act. DAFF's (2010) report emphasised the need for cooperatives to adhere to the cooperative act of operating functional saving facilities like the banks operate under the cooperatives' name. Evidence from this study shows that most cooperatives are following this act. However, some cooperatives keep cooperative reserves in safes or members' personal accounts as alternative saving facilities or for emergencies (Table 6). This goes against the cooperative act, which could give rise to conflicts amongst members as transparency and efficient management of cooperative resources may be questioned, and continuous conflicts, especially regarding finances, could lead to the failure of any organisation. Sixty percent of respondents said that cooperative members had received financial management training, although 40% said the training had only been given once since the cooperatives were founded (Table 7). Zhang and Liu's (2018) standpoint is that the government could provide an adequate support system for training_cooperative members on financial management to strengthen their competency in managing cooperative finances. This would invariably mitigate poor financial management and potential conflicts among its members. Results revealed that 70% of the cooperatives rarely have internal conflicts as members mostly agree to differ (Table 8). It is critical to note that only representatives of each cooperative were interviewed for this survey. As such, the respondents may not have fairly represented the views of other members. In the opinion of Nganwa, Lyne and Ferrer (2010), one of the major causes of conflicts among members of cooperatives is the lack of transparency, particularly, when members are not privy to or provided with up-to-date operational information of the cooperatives. This could also lead to the collapse of any cooperative society. About 80% of the respondents indicated that the cooperative chairpersons and board of directors usually act as arbitrators (Table 8). This observation was also made in Benson's (2014) study, where cooperatives primarily tend to rely on their executive members to resolve internal conflicts. However, more conflicting issues may arise when the cooperative executive's personal interests oppose and suppresses those of the floor or general members (Yang, Klerkx & Leeuwis, 2014; Herbel et al., 2015).

The Cooperative Act No. 14 of 2005 emphasised the need for cooperatives to follow its 5th principle, which states that education, training and information must be provided by cooperatives for their hired managers, board members and members in general to give room for effective cooperative performance (Fici, 2012; Kumar, Wankhede & Glen, 2015; Tortia, 2018). Findings on conflict management training showed that most (90%) cooperatives have not had training on conflict management (Table 8). Even though the majority of the cooperatives claimed to have organised training for its members on record keeping (Table 5) and financial management (Table 7), further investigations revealed that the majority of the cooperatives either indicated that the training was executed only once since their establishment or that the frequency of training for their members was below par. The issue of educating and training cooperative members not only on conflict management, record keeping and financial management but also on sustainable agricultural production practices is particularly vital. Supporting cooperative members to acquire skills in organisation management, entrepreneurship, farming techniques, quality control, technical training on agricultural best practices, post-harvest handling, numeracy, and financial literacy would positively impact cooperative societies as a body (Gelo, Muchapondwa & Shimeles, 2017; Lowe, Njambi-Szalapka & Phiona, 2019). Aside from that, making training accessible to cooperative members further motivates them to become active cooperative members with a common goal of achieving their organisational goals (Cheruiyot & Ogendo, 2012). In Garnevska, Liu and Shadbolt (2011) view, the effective growth of cooperatives depends on their knowledge, competency and technical skills mainly acquired through training courses. For example, Anania and Rwekaza (2018) study provided evidence which suggested that the training of cooperative members by banking institutions and non-governmental organisations on financial management and leadership, business planning, entrepreneurship, membership rights and obligations, greatly improved the efficiency of the cooperatives. Cheruiyot and Ogendo (2012) as well as Masuku, Mutangira and Masuku (2016), emphasised the importance of continuously training and educating cooperative members to enhance their capacities and socio-economic empowerment.

The majority (80%) of cooperatives indicated that there is some form of interaction between the cooperatives and extension field officers; the frequency of interactions is mostly monthly (30%), quarterly (20%) and yearly (20%) (Table 9). According to the respondents, the frequency of interactions differs as there is no consistent approach to meetings with the officers; interactions only occur when there is a need, and the cooperatives usually impel the meeting. According to Arayesh (2017), Msimango and Oladele (2017), Elahi, Abid, Zhang, ul Haq and Sahito (2018), Mersha and Ayenew (2018), it is expected that there should be recurring interactions between cooperatives and extension personnel. This study showed that although the level of interactions between the cooperatives and officers is fair, there is still the need to improve the frequency of extension visits, training and follow-up appointments with cooperative members. The marginal rate of cooperative follow-up visits could be because the municipality has insufficient extension personnel (Yusuf, Masika & Ighodaro, 2013). To bridge some of the gaps, the agriculture department created and equipped companies like Ncera Farms (Pty) Ltd in the Eastern Cape Province to advise, train, and deliver agricultural extension services, mechanisation of agricultural production to farmers and close communities on vegetable and other kinds of agricultural production (DAFF, 2014). However, a higher percentage (50%) of the cooperatives claimed that the extension officers only visit them to provide some form of advisory services but have never organised special training programmes on vegetable production for cooperative members (Table 9). This result further highlights the continuous lack of training cooperative members in the study area. There is a need for extension institutions in the region to initiate vegetable production training schemes for cooperative members to broaden their level of expertise, which could hugely influence the sustainability of vegetable production and the cooperative societies in the long term.

5. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Outcomes from this study showed that members were mostly involved in the daily running of the cooperatives, governance, and decision-making processes. Most cooperatives are constrained by the lack of training of their members on conflict resolution, record-keeping and financial management. The role of extension services towards the sustainability of the cooperatives is important. Many cooperatives indicated some level of interaction between the cooperatives and extension personnel in the study area. Therefore, there is a need to improve the frequency of extension visits, training, and follow-up appointments.

REFERENCES

ABATE, G.T., FRANCESCONI, G.N. & GETNET, K., 2014. Impact of agricultural cooperatives on smallholders' technical efficiency: empirical evidence from Ethiopia. Annals of Pub. Coop. Eco, 85(2): 257-286. [ Links ]

ABEBAW, D. & HAILE, M.G., 2013. The impact of cooperatives on agricultural technology adoption: empirical evidence from Ethiopia. Food Pol., 38: 82-91. [ Links ]

ANANIA, P. & RWEKAZA, G.C., 2018. Cooperative education and training as a means to improve performance in cooperative societies. Sumerianz. J. Soc. Sci., 1(2): 39-50. [ Links ]

ARAYESH, M.B., 2017. The relationship between extension educational and psychological factors and participation of agricultural cooperatives' members (case of Shirvan Chardavol county, Ilam, Iran). Int. J. Agric. Man. Dev., 7(1): 79-87. [ Links ]

CHEBET, M. & KENNEDY, O.B.M., 2019. Effect of budgeting on financial sustainability of dairy cooperative societies in Uasin Gishu County, Kenya. Int. J. Recent Res. Interdisciplinary Sci. (IJRRIS)., 6(4): 1-15. [ Links ]

CHEPKWEI, A.K., WANYOIKE, D. & KOIMA, J., 2017. Influence of strategic leadership on effective strategy implementation among savings and credit cooperative societies in Kenya. Eur. J. Bus. Strategic Man. (EJBSM)., 2(9): 55-70. [ Links ]

CHERUIYOT, T.K. & OGENDO, S.M., 2012. Effect of savings and credit cooperative societies strategies on member' s savings mobilization in Nairobi, Kenya. Int. J. Bus, Com, 1(11): 40-63. [ Links ]

CHIBANDA, M., ORTMANN, G.F. & LYNE, M.C., 2009. Institutional and governance factors influencing the performance of selected smallholder agricultural cooperatives in KwaZulu-Natal. Agrekon., 48(3): 293-301. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FORESTRY & FISHERIES., 2010. Guidlines for establishing agricultural cooperatives. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FORESTRY & FISHERIES., 2014. Annual report 2013/14. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FORESTRY & FISHERIES., 2016. Annual report 2015/16. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FORESTRY & FISHERIES., 2017. Annual report 2016/17. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF TRADE & INDUSTRY., 2012. Integrated strategy on the development and promotion of cooperatives. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

EASTERN CAPE PLANNING COMISSION., 2014. Eastern Cape vision 2030 provincial development plan. Bisho: Government Printer. [ Links ]

ELAHI, E., ABID, M., ZHANG, L., UL HAQ, S. & SAHITO, J.G.M., 2018. Agricultural advisory and financial services; farm level access, outreach and impact in a mixed cropping district of Punjab, Pakistan. Land Use Pol., 71: 249-260. [ Links ]

FICI, A., 2012. Cooperative identity and law. [ Links ]

GARNEVSKA, E., LIU, G. & SHADBOLT, N.M., 2011. Factors for successful development of farmer cooperatives in Northwest China. Int. FoodAgribus. Man. Rev., 14(4): 69-79. [ Links ]

GELO, D., MUCHAPONDWA, E. & SHIMELES, A., 2017. Return to investment in agricultural cooperatives in Ethiopia. Ethiopia. [ Links ]

HERBEL, D., ROCCHIGIANI, M. & FERRIER, C., 2015. The role of the social and organisational capital in agricultural co- operatives ' development practical lessons from the CUMA movement. J. Co-op. Org. Man., 3: 24-31. [ Links ]

KESHELASHVILI, G., 2017. Characteristics of management of agricultural cooperatives in Georgia. In 32nd International Academic Conference. Georgia. [ Links ]

KING SABATA DALINDYEBO., 2014. Integrated development plan 2013-14 review final draft. Mthatha. [ Links ]

KUMAR, V., WANKHEDE, K.G. & GENA, H.C., 2015. Role of cooperatives in improving livelihood of farmers on sustainable basis. American J. Edu. Res., 3(10): 1258-1266. [ Links ]

LEVY, W., 2017. Cooperatives: Farmers work together for a better future: Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation (CTA). Available from http://www.jstor.org/stable/44190947. [ Links ]

LOWE, A., NJAMBI-SZALAPKA, S. & PHIONA, S., 2019. Youth associations and cooperatives: Getting young people into work. London. [ Links ]

MERSHA, D. & AYENEW, Z., 2018. Financing challenges of smallholder farmers: a study on members of agricultural cooperatives in Southwest Oromia Region, Ethiopia. African J. Bus. Manag, 12(10): 285-293. [ Links ]

MSIMANGO, B. & OLADELE, O.I., 2017. Factors influencing farmers' participation in agricultural cooperatives in Ngaka Modiri Molema District. J. Hum. Eco., 44(2): 113119. [ Links ]

MUSAH, A. & IBRAHIM, M., 2014. Record keeping and the bottom line: Exploring the relationship between record keeping and business performance among small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in the Tamale Metropolis of Ghana. Res. J. Fin. Acc., 5(2): 107-117. [ Links ]

MZUYANDA, C., 2014. Assessing the impact of primary agricultural cooperative membership on smallholder farm performance (crops) in Mnquma Local Municipality of the Eastern Cape Province. Masters Dissertation, University of Fort Hare. [ Links ]

NGANWA, P., LYNE, M. & FERRER, S., 2010. What will South Africa's new cooperatives Act do for small producers? an analysis of three case studies in KwaZulu-Natal. Agrekon., 49(1): 39-55. [ Links ]

ORTMANN, G.F. & KING, R.P., 2006. Small-scale farmers in South Africa: can agricultural cooperatives facilitate access to input and product markets? Available from http://purl.umn.edu/13930. [ Links ]

ORTMANN, G.F. & KING, R.P., 2007. Agricultural cooperatives I: History, theory and problems. Agrekon., 46(1): 18-46. [ Links ]

REBELO, J.F., LEAL, C.T. & TEIXEIRA, Â., 2017. Management and financial performance of agricultural cooperatives: a case of Portuguese olive oil cooperatives. Revista de Estu. Coop., 123: 225-249. [ Links ]

THABA, S.C. & MBOHWA, C., 2015. The nature, role and status of cooperatives in South African context. In World Congress on Engineering and Computer Science. V2. San Francisco. [ Links ]

THABA, K., ANIM, F.D.K. & TSHIKORORO, M., 2017. Analysis of factors affecting proper functioning of smallholder agricultural cooperatives in the Limpopo Province of South Africa. J. Hum., Eco, 54(3): 150-157. [ Links ]

TORTIA, E.C., 2018. The firm as a common. Non-divided ownership, patrimonial stability and longevity of cooperative enterprises. Sustainability., 10. DOI: 10.3390/su10041023. [ Links ]

TSHUNUNGWA, B.G., 2013. The role of agricultural cooperatives in developing previously disadvantaged black rural communities in the Eastern Cape Province since 2005: The case study of Cannon farm in Queenstown. Degree Mini-dissertation, Nelson Mandela University. [ Links ]

TWALO, T., 2012. The state of cooperatives in South Africa. Available from http://www.lmip.org.za/sites/default/files/documentfiles/13_TWALO_Cooperatives.pdf. [ Links ]

VERHOFSTADT, E. & MAERTENS, M., 2015. Can agricultural cooperatives reduce poverty? Heterogeneous impact of cooperative membership on farmers' welfare in Rwanda. Applied Eco. Persp. Pol., 37(1): 86-106. [ Links ]

YANG, H., KLERKX, L. & LEEUWIS, C., 2014. Functions and limitations of farmer cooperatives as innovation intermediaries: findings from China. Agric. Sys., 127: 115125. [ Links ]

YUSUF, S.F.G., MASIKA, P. & IGHODARO, D.I., 2013. Agricultural information needs of rural women farmers in Nkonkobe Municipality: the extension challenge. J. agric. Sci., 5(5): 107-113. [ Links ]

ZHANG, L. & LIU, S., 2018. Financial management in new types of agricultural businesses: a case study of farmer's cooperatives in Weixian county. Asian Agric. Res., 10(3): 10-14. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

S.F.G. Yusuf

Email: fyusuf@ufh.ac.za