Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Agricultural Extension

On-line version ISSN 2413-3221

Print version ISSN 0301-603X

S Afr. Jnl. Agric. Ext. vol.51 n.3 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2413-3221/2023/v51n3a13952

ARTICLES

Assessing Awareness and Perceptions Towards the Existence of Indigenous Foods in Port St Johns of the Eastern Cape South Africa

Ntlanga S.S.I; Jiba P.II; Christian M.III; Mdoda L.IV

IPhD student, School of Agricultural, Earth and Environmental Sciences. College of Agriculture, Engineering and Science. Discipline of Agricultural Economics. University of KwaZulu Natal, 62 Carbis Road, Scottsville, Pietermaritzburg, 3201, samuelntlanga@gmail.com; Orcid: 0009-0005-4497-8507

IIPhD Student, Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension, North-West University, Mahikeng Campus, Private Bag X2046, Mmabatho, 2745, phiwejiba@gmail.com; ORCID: 0000-0003-0648-7254

IIISenior Lecturer, Department of Agricultural Sciences, Nelson Mandela University, Port Elizabeth, 6031, mzuyanda1990@gmail.com, Orcid 0000-0003-4446-0298

IVSenior Lecturer, Discipline of Agricultural Economists, School of Agriculture, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, P/Bag X01, Scottsville, Pietermaritzburg, 3209, South Africa. ORCID: 0000-0002-5402-1304

ABSTRACT

Intolerably high rates of food insecurity and micronutrient deficiencies still prevail at an alarming rate in rural poor communities that practice subsistence farming. Even though indigenous fruits and vegetables are abundantly available and are easily accessible in these rural communities. The consumption of indigenous vegetables and fruits can combat food insecurity and micro-nutrient deficiencies in resource-constrained communities. This is attributed to negative perceptions shared among rural communities, specifically the younger generation, who are unaware of indigenous foods. Against this background, the study was developed to assess awareness and perceptions towards indigenous fruits and vegetables in Port St. Johns of the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. A multi-stage sampling technique was used to evaluate the availability of the perceptions of households and the contribution of indigenous fruits and vegetables to household food security. A total of 340 respondents were purposively selected in the study area. A positive impact on household food security was revealed, suggesting that consuming indigenous fruits and vegetables may address rural household dietary diversity and food insecurity. The study argues that indigenous fruits and vegetables may be used as a food security coping strategy at the household level in rural areas, given their availability, especially in summer. Additionally, dispelling several negative perceptions and targeting consumption drivers will enhance the food security nexus of indigenous fruits and vegetables at the household level.

Keywords: Consumption of Indigenous Fruits and Vegetables, Food Security, Indigenous Fruits and Vegetables, Rural Households.

1. INTRODUCTION

South Africa is endowed with a great variety of indigenous fruits and vegetables, and more than 100 different traditional vegetables have been found, particularly in rural areas (Lewu & Mavengahama, 2010; Dweba & Mearns, 2011; Ntuli et al., 2012). According to Schippers (2000), indigenous fruit and vegetable food plants are planted whose parts, such as young, succulent stems and young fruits, are culturally accepted and consumed as foods in different regions and locations of the world. Research also highlights that different tribal people use other concepts to refer to indigenous vegetables. For instance, the Sotho and Pedi tribes called it morogo, whereas the Zulu and Xhosa tribes use the term imifino, which collectively means indigenous vegetables (Jansen van Rensburg et al., 2007). Abukutsa-Onyango (2007) further argued that indigenous fruits and vegetables vary according to location and climatic conditions and are specific to ethnic groups. In addition, Vorster et al. (2007) concluded that indigenous fruits and vegetables vary according to seasons indigenous fruits and vegetables' availability varies according to seasons. Similarly, Jansen van Rensburg et al. (2007) observed that indigenous vegetables are more abundant during summer than in winter but are highly perishable. It has been reported that some of these species have been domesticated or are semi-domesticated, while most of them grow as weeds in cultivated farms or wild in uncultivated fields (Matenge et al., 2011; Vorster et al., 2007; Jansen van Rensburg et al., 2007).

Other studies have reported that rural people perceive the populations of indigenous vegetables and fruits to be in decline (Adedoyin & Taylor, 2000; Shackleton, 2003; Vorster et al, 2007). In addition, literature further argues that, for seemingly abundant indigenous foods, people seldom consume all available plant material but are rather selective depending on certain (un)desirable characteristics like leaf hairiness, astringency (bitterness) and leaf size (which influences ease and speed of gathering/harvesting). As a result, not all that is available is consumed (Mavengahama, 2013).

Therefore, the claims of abundance and availability of indigenous foods have not been adequately determined (Mavengahama, 2013). Despite that, such studies regarding their availability are important as a preliminary step in breeding these species for desirable traits. These may include low anti-nutrients and low astringency, high micronutrient content, as well as high yield of the edible parts (Mavengahama, 2013). The literature further suggests that even the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) database on vegetable production in sub-Saharan Africa fails to capture African leafy vegetables currently used by the subcontinent (Smith & Eyzaguirre, 2007).

2. LITERATURE REVIEW: ATTITUDES AND PERCEPTIONS OF RURAL PEOPLE ON INDIGENOUS FOODS

According to Taleni and Goduka (2013), the most popular indigenous foods are collected or harvested from the wild rather than cultivated. Notably, indigenous fruits and vegetables are declining in rural areas of South Africa (Jansen van Rensburg et al., 2007). Further, the literature explained that South African communities associate the consumption of indigenous foods with poverty and low self-esteem (Cloete & Idsardi, 2012; Modi et al., 2006; Jansen van Rensburg et al., 2007; Majova, 2014). Moreover, the youth and urbanised people have a negative attitude and are unaware of indigenous foods, as they are considered food for poor people and the old-fashioned (Jansen van Rensburg et al., 2007). Further, lack of awareness of indigenous foods' nutritional status (Vorster et al., 2007; Dweba and Mearns, 2011), as well as their association with poverty and primitiveness, are some of the reasons that discourage the youth from learning about indigenous vegetables and fruits (Faber et al., 2010; Dweba & Mearns, 2011; Thandeka et al., 2011; Ntuli et al, 2013).

In Southern Africa, the agricultural system has changed in commercial and subsistence farming, aimed at cash crop production (Abukutsa-Onyango, 2007; Jansen van Rensburg et al., 2007). However, this farming promoted mono-cropping and encouraged the removal of indigenous vegetables in the fields as they were regarded as weeds. Moreover, this attitude towards indigenous vegetables still prevails among research communities. Policymakers and extension advisors continue to advise farmers to eradicate them from their fields and gardens (Jansen van Rensburg et al., 2007). Unquestionably, the same is not true in subsistence farming, where women do most of the weeding and tend to pull out the unwanted weeds and leaving the useful weeds for later use (Jansen van Rensburg et al., 2007; Taleni & Goduka, 2013).

Cloete and Idsardi (2012) claimed that the association of indigenous foods with poverty and low self-esteem among rural people stems from socioeconomic and cultural changes among African consumers. In addition, Vorster et al. (2007) claimed that attitudes and perceptions are divided by gender and cultural groups, but generally, indigenous foods are perceived to be part of traditional diets. The same author also explained that in South Africa, the Zulu, Shangaan, Swazi, Tshonga, Pedi, and Ndebele men do not always prefer to consume indigenous vegetables as a relish. On the other hand, the Xhosa males considered the indigenous vegetables as food meant for women and, thus, preferred to eat meat. The same is true as Kepe (2008) declared that men seem to care less about indigenous vegetables before they are collected and prepared than women.

Vorster et al. (2007) concluded that the attitude is assessed based on the taste and plant choice among men and women. Further, Vorster et al. (2007) confirmed that generally, men prefer the bitter taste of blackjack (Bidens pilosa L), even though they are used in the mix of leaves to add flavour to the dish. Also, it is noted that both women and men prefer amaranth and pumpkin leaves as relish to increase taste in their dishes (Modi et al., 2006; Ntuli et al., 2012; Vorster et al., 2007). However, a lack of information on the cooking methods that would make indigenous foods more attractive to younger people is likely to result in a decline in consumption (Dweba & Mearns, 2011).

Some studies have reported that younger generation in communities has a negative attitude towards indigenous foods (Van der Hoeven et al., 2013; Vorster et al., 2007; Dweba & Mearns, 2011). Thandeka et al. (2011) mentioned that the younger generation disliked indigenous foods due to unfamiliar tastes and ignorance of the preparation methods. Dweba and Mearns (2011) also observed that the young women in the eMantlaneni village shared the same attitude towards indigenous foods. There is a dearth of literature that addresses the possible strategies that can be used to make indigenous foods more attractive to the younger generation. There is a need to determine other factors influencing the younger generation's attitudes towards consuming indigenous fruits and vegetables.

3. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

The study was conducted in Port St. Johns, located in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. Port St. Johns is a small coastal town with various hills, dunes, rivers, and mountainous terrain (OR Tambo District Municipality Integrated Development Plan, 2010). Port St. Johns falls under the Port St. Johns Local Municipality, which belongs to the OR Tambo District Municipality. The area is located approximately 90 km away from Mthatha (Port St Johns Local Municipality Integrated Development Plan, 2016).

3.1. Methods and Research Instruments

This study was conducted on the baseline data of the rural households that consumed indigenous foods and those that did not. A cross-sectional survey research design was used in the study. Both multi-stage and probability sampling approach was used in this study area. Using a probability sampling approach, the researcher managed to draw a sample size of 340 out of 670 household heads in these four villages due to limited resources and time constraints. The sample size of 340 was a reasonable size that represents the study area's population.

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

The data was collected from the respondents in the study area. A questionnaire was used as a tool to gather information from the respondents. The questionnaire covers both qualitative and quantitative research questions. Qualitative research includes verbal data such as opinions, respondent's experiences, and feelings about a particular issue. In the case of this study, the respondents' perceptions of indigenous fruits and vegetables, their food security status, and their views about the availability of indigenous fruits and vegetables in the study area.

On the other hand, the quantitative method focuses on numerical data, which is useful in statistical data analysis methods. Hughes (2006) noted that the quantitative information validates the description of a research phenomenon. However, the weakness of one method was nullified by the strengths of the other (Jiba, 2017). Furthermore, quantitative data includes the respondents' age, income level and family size. Also, a questionnaire included personal information such as age, gender, level of education, marital status, and occupation. Data was collected in November 2016 when indigenous fruits and vegetables were abundantly available in the summer.

The data was sorted, coded, and summarised in Microsoft Excel. Stata version 15 was used to analyse the coded data whereby frequencies, counts and percentages were presented as tables and charts. The objectives of the study and their analytical tools are shown in Table 1

4. DISCUSSION AND FINDINGS: DEMOGRAPHIC FACTORS OF THE RESPONDENTS

The result from demographic background indicates that 36.5% of the respondents were between the ages of 20 and 39. Also, 36.8% of them were between 40 and 59 years of age, while 26.7 % were above 60. However, these indigenous foods are consumed mainly by older adults. Gender plays a significant role in consuming indigenous fruits and vegetables because rural female-headed families tend to be poor. This is because most of these women aren't educated; as a result, they either do not have jobs or have informal jobs and rely a lot on social grants. Thus, one can speculate that these indigenous fruits and vegetables greatly supplement the "exotic" foods. The results revealed that most respondents (56.5%) were males and 43.5% were females. This means that, in most cases, the males are the ones who consume these indigenous foods. Marital status shows that 35.9% of the respondents were single, and 64.1% were married. More than half of the respondents had attained secondary (57.9%) education, followed by those who had attained only primary (25.6%) and 16.5% had no formal education.

The results further indicate that 37.7% of the respondents had more than four family members, while 30.3% had large family sizes. In terms of occupation, 27% of the respondents were informally employed, and 42.7% of the respondents were unemployed. Approximately 18.7% of the respondents were involved in business, while 11.5% were formally employed. It is noted that 42.7% of the respondents earned their monthly income from social grants, and 27.1% earned their income from informal employment. Also, 18.7% of the respondents earned income from business, and 11.5% received income salaries. It is noted that half of the respondents received an amount that ranged between R1 100 and R2 000, while 26.1% of the respondents earned less than R1 000. Regarding hectares, 51.8% of the respondents own one to 3 hectares of land, while 35.3% own less than one hectare of land.

4.1. Rural Households' Perceptions of Indigenous Fruits and Vegetables Consumption

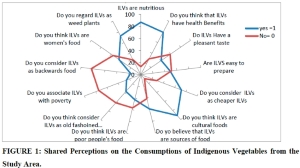

This section presents the results of shared perceptions on consuming indigenous fruits and vegetables from the study area. Figures 1 and 2 below present the summarised perceptions and attitudes on indigenous fruit and vegetable consumption shared by the respondents in the study area.

4.2. Shared Perceptions on the Consumption of Indigenous Vegetables

Figure 1 presents the perceptions of indigenous vegetables.

From the study area, the results revealed that 87.1% of the respondents believed that indigenous vegetables are nutritious, and 12.9 % objected to that perception. The findings indicate that most of the respondents from the study area associated indigenous vegetables with nutritious foods. Most respondents from the study area associated indigenous vegetables with nutritious foods, which may trigger the consumption of indigenous vegetables. Several previous studies support these findings by highlighting that indigenous vegetables are known as sources of both micro and macronutrients (Modi et al., 2006; Maroyi, 2011; Taleni & Goduka, 2013; Jansen van Rensburg et al, 2004; Abukutsa-Onyango et al., 2010).

Concerning perceptions related to health benefits, the results indicated that 79.4% of the respondents believed that indigenous vegetables have health benefits, and 29.6% did not believe that indigenous vegetables had any health benefits. The findings suggest that most of the respondents share positive perceptions of indigenous vegetables regarding health benefits, which may positively influence the use of indigenous vegetables. Similar findings were shared by Demi (2014), Matenge et al. (2011) and Thandeka et al. (2011), who reported that indigenous vegetables play a crucial role in combating chronic diseases such as HIV/AIDS.

Figure 1 further shows that 58.8% of the respondents did not believe indigenous vegetables have a pleasant taste, which may negatively affect their consumption. Whereas 41.2% of the respondents thought that indigenous vegetables had a pleasant taste. Similar observations were shared by Taleni & Goduka (2013), who argued that indigenous vegetables have low status in many communities, possibly due to their bitter taste.

Results also indicate that 51.1% of the respondents did not believe indigenous vegetables are easy to prepare, while the rest believed that indigenous vegetables are easy to prepare. The results suggest that most of the respondents believe that indigenous vegetables are not easy to prepare. This may negatively influence households' use of indigenous vegetables as they may prefer exotic vegetables. Contrary to these findings, Vorster et al. (2007) argued that the soft, fast-cooking leaves of pumpkin and nightshade species are preferred to the finery leaves of cowpeas, and the recipes used to prepare the different leafy vegetables tend to be homogenous within cultural groups limiting culinary diversity.

Figure 1 further indicates that 71.8% of the respondents believed indigenous vegetables are cheaper than exotic vegetables. The results suggested that most respondents believed that indigenous vegetables are cheaper, which may encourage people to participate in their consumption. The study's results align with the observations made by Vorster et al. (2007), who revealed that indigenous vegetables are widely and freely available.

The results also indicated that 90.9 % of the selected respondents believed indigenous vegetables are cultural foods, and only 9.1% did not believe indigenous vegetables are cultural foods. The results suggest that most respondents share positive perceptions of indigenous vegetables concerning cultural food beliefs, which may promote their consumption. Similarly, the study's conclusions by Taleni & Goduka (2013) reported that Pedi people considered collecting and consuming indigenous vegetables as part of their culture as the Pedi Proverb conveys that "meat is a visitor, but morogo is our daily food". Also, Jansen van Rensburg et al. (2007) revealed that some parts of South Africa indicated differences in cultural preferences for indigenous and the practice of mixing indigenous vegetables in dishes is common.

Figure 1 further indicates that 58.8% of the respondents believed indigenous vegetables are their food source. The results suggest that most people share positive perceptions regarding indigenous vegetables as a source of food, and this belief may promote the consumption of indigenous vegetables. These findings align with the perceptions shared by Vorster et al. (2007), who acknowledged that indigenous vegetables are additional sources of food due to their ability to grow in these generally marginal areas. Moreover, they are used as food sources, especially during winter, as a source of dried food.

Indigenous vegetables are known as food for the poor, old-fashioned food associated with poverty, seen as food for women, labelled as food for backward people and seen as weeds (Jansen van Rensburg et al., 2007; Vorster et al., 2007; Cloete & Idsard, 2012; Thandeka et al, 2011). However, Figure 1 deduced that 42.9% of the respondents from the study area believed that indigenous vegetables are poor people's food, while 57.1% did not believe so. In addition, the results revealed that 37.4% of the respondents shared the perception that indigenous vegetables are regarded as old-fashioned food. Results further showed that 25.3% of the respondents from the study area associated indigenous vegetables with poverty. In comparison, 74.7% of the respondents did not believe that indigenous vegetables are associated with poverty; generally, these results indicated that people from the study area share positive perceptions towards consuming indigenous vegetables.

4.3. Availability of Indigenous Fruits in the Study Area

Table 4 represents common indigenous fruits that are available in the study area. The communities listed the major indigenous fruits available in the study area during the study period. The indigenous fruit species reported to exist include Amavilo, Usobaba, Iintongwane, Ubuqholo, South African blackberry, Cape fig, and Wild plum. These findings indicate that there is a high availability of several indigenous fruits during the summer season.

There is a convergence of previous studies which acknowledges the availability of indigenous fruits in rural areas during summer (Kalaba et al., 2009; Shava, 2005; Schreckenberg et al., 2006; Ekesa et al., 2009; Oladele, 2011; Elago & Tjaveondja, 2015). Rural households who consume indigenous fruits are assumed to be more food secure due to the high availability of different varieties of indigenous fruits during the rainy season. For instance, rural people tend to harvest in large quantities of different varieties of indigenous fruits. By so doing, the consumers of indigenous fruits will be food secure. The high availability of indigenous fruits will positively impact rural household food security. Apart from their availability, the rural people's perceptions towards the indigenous fruits and vegetables play a crucial role in their acceptance as the food in rural areas. Thus, the following section addresses the people's perceptions of the consumption of indigenous fruits and vegetables.

The findings suggest a high availability of different varieties of indigenous vegetables from the study area during summer. The findings of the study are supported by extant literature, which highlights that indigenous vegetables are abundantly available in rural areas during the summer season (Vorster et al., 2007; Jansen van Rensburg et al., 2007; Legwaila et al., 2011; Maroyi, 2011; Oladele, 2011; Mahlangu, 2014). The high availability of indigenous fruits and vegetables ensures that rural people who consume indigenous fruits and vegetables will be more food secure during the rainy season. This implies that rural people can collect large quantities of indigenous fruits and vegetables during summer.

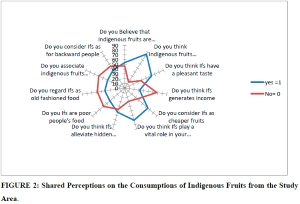

4.4. Shared Perceptions on the Consumption of Indigenous Fruits

This section presents rural households 'perceptions of indigenous fruits and vegetable consumption, as summarised in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2 revealed that 53.5% of the respondents from the study area believed that indigenous fruits are nutritious, and 46.5% of the respondents were opposed to these findings. The study's findings further suggested that most respondents from the study area perceive indigenous fruits as nutritious foods. Both men and women respondents reported that they often consume indigenous fruits in the bush when they fetch the wood. The findings are consistent with those reported by Modi et al. (2006), Jansen van Rensburg et al. (2004), Schreckenberg et al. (2006), Kalaba (2007) and Oladele (2011), who argued that indigenous foods (ALVs and Ifs) are known as the important sources of both micro and macronutrients.

Figure 2 indicated that 85% of the respondents believed that indigenous fruits have health benefits, while 15% of the respondents did not believe that indigenous fruits had any health benefits. The findings suggested that most people shared positive perceptions regarding the health benefits of indigenous fruits, which may positively influence their consumption. Similar observations were reported by Flyman and Afolayan (2006) and Van Jaarsveld et al. (2014), who elaborated that indigenous foods (ALVs and Ifs) are essential sources of micronutrients, including A and C, iron, zinc, folate and other nutrients, minerals and roughage needed to maintain health.

Furthermore, the study's results showed that 62.4% of the respondents believed indigenous fruits taste pleasant. The findings indicated that most of the people from the study area believe that indigenous fruits have a pleasant taste, which may increase the intake of indigenous fruits by rural households. Similar findings were shared by Kalaba (2007), who reported that indigenous fruits in western Kenya are used in porridge as a substitute for sugar by rural people who do not have sugar due to their pleasant taste.

Concerning income generation, the results indicated that 68.2% of the respondents disagreed with the perception that indigenous fruits generate income. The findings indicate that most people did not believe in the income-generating potential of indigenous fruits. Previous studies noted that there is potential to generate income through indigenous fruits sold in rural informal markets (Mpala et al, 2015; Kalaba, 2007; Elago & Tjaveondja, 2015).

Figure 2 further showed that 68.2% of the respondents believed indigenous fruits are cheaper than exotic fruits. The findings align with the reports of Matenge et al. (2011), who noted that indigenous foods represent cheap but quality nutrition to the poor in urban and rural areas where malnutrition is widespread.

Emerging from the study results was that 70.9% of the respondents believed that indigenous fruits are cultural fruits, and 29.1% of the respondents did not. The results showed that most of the people associated the consumption of indigenous fruits with their culture. The respondents indicated that indigenous fruits are part of their culture because even their forefathers were consuming indigenous fruits. Similar findings were shared by Ekesa et al. (2009), who highlighted that indigenous fruits are often part of the traditional diet and culture and the subject of a body of indigenous knowledge regarding their use.

Regarding perceptions that indigenous fruits alleviate hidden hunger, the results showed that 53.2% of the respondents shared the perception that indigenous fruits do alleviate hidden hunger, and 46.8% did not believe so. The results revealed that most of the respondents believed that indigenous fruits alleviate hidden poverty, and this meant that most of the people were bound to consume them. The results are consistent with several general comparable findings of Legwaila et al. (2011), Jansen van Rensburg et al. (2004), Vorster et al. (2007), Maroyi, (2011), Schreckenberg et al. (2006), Oladele (2011), Kalaba (2007), Ekesa et al. (2009), Haule (2016) and Mithofer et al., (2006) who reported that indigenous foods have the potential to manage hidden hunger and play a crucial role in household food security for the poorer rural people.

Contrary to popular belief that indigenous fruits are regarded as food for poor people (Cloete & Idsardi, 2012; Modi et al, 2006; Jansen van Rensburg et al, 2007; Oladele, 2011; Kalaba, 2007; Haule, 2016; Mithofer et al, 2006; Ekesa et al, 2009; Schreckenberg et al, 2006), the results from the study revealed otherwise. For instance, it could be deduced from the study's findings that 58.8% of the respondents did not believe indigenous fruits are food for poor people, and 41.2% believed that indigenous fruits are food for poor people. The findings from the study suggested that respondents share positive perceptions regarding the consumption of indigenous fruits.

Generally, most people share positive perceptions about the consumption of indigenous fruits and vegetables. This means that rural people still believe that indigenous fruits and vegetables have a potential contribution towards household food security. Given the positive perceptions shared by the rural communities, it is necessary to look at the potential contribution of indigenous fruits and vegetables to household food security. This information is crucial in promoting the consumption of indigenous fruits and vegetables. The following section discusses indigenous fruits and vegetables' potential contribution to household food security.

5. CONCLUSION

The results of the study in the second objective revealed that most people from the study area share positive perceptions towards indigenous fruits and vegetables. The most shared positive perceptions were that (a) indigenous fruits and vegetables are nutritious, (b) they serve as a source of food, (c) they are cheaper and (d) they have health benefits. However, some negative perceptions emerged from the results towards indigenous fruits and vegetables. The most shared negative perceptions were that (a) indigenous fruits and vegetables are associated with poverty, (b) they are regarded as food for the poor, (c) they are also regarded as women's foods, (d) in some incidences they are regarded as weeds and (e) lastly, they are also considered as old-fashioned foods.

The study concludes that indigenous fruits and vegetables were abundantly available in the summer season from the study area and positively perceived by most of the respondents. However, some negative perceptions were noted in some areas. Several socio-economic factors (gender, age, level of education, household size, garden size, access to formal markets and access to formal credit) were noted as possible drivers of indigenous fruits and vegetable consumption at the household level.

6. CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

ABUKUTSA-ONYANGO, M.O., ADIPALA, E., TUSIIME, G. & MAJALIWA, J.G.M., 2010. Strategic repositioning of African indigenous vegetables in the Horticulture Sector. Paper presented at Second RUFORUM Biennial Regional Conference on "Building capacity for food security in Africa", 20 -24 September, Entebbe, Uganda, 1413-1419. [ Links ]

ADEBOOYE, O.C. & OPADODE, J.T., 2004. Status of conservation of the indigenous leaf vegetables and fruits of Africa. Afr. J. Biotechnol., 3(12): 700 - 705. [ Links ]

CLOETE, P.C. & IDSARDI, E., 2012. Bio-fuels and food security in South Africa: The role of indigenous and traditional food crops. Paper presented at International Association of Agricultural Economists Conference, 18 - 24 August, Foz do Iguacu, Brazil, 1-30. [ Links ]

FABER, M., OELOFSE, A., VAN JAARSVELD, P.J., WENHOLD, F.A. & JANSEN VAN RENSBURG, W.J., 2010. African leafy vegetables consumed by households in the Limpopo and KwaZulu-Natal provinces in South Africa. South Afr J Clin Nutr., 23(1): 30-38. [ Links ]

LEWU, F.B. & MAVENGAHAMA, S., 2010. Wild vegetables in Northern KwaZulu Natal, South Africa: Current status of production and research needs. Sci. Res. Essay., 5(20): 3044-3048. [ Links ]

DEMI, S.M., 2014. African indigenous food crops: Their roles in combatting chronic diseases in Ghana. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Toronto, Canada. [ Links ]

DWEBA, T.P. & MEARNS, M.A., 2011. Conserving indigenous knowledge as the key to the current and future use of traditional vegetables. Int. J. Inf. Manag., 31(6): 564-571. [ Links ]

ELAGO, S.N. & TJAVEONDJA, L.T., 2015. Socio-Economic Importance of two Indigenous Fruit Trees: Strychnos Cocculoides and Schinziophyton Rautanenii to the people of Rundu Rural West Constituency in Namibia. EJPAS., 3(2): 16-26. [ Links ]

EKESA, B.N., WALINGO, M.K. & ONYANGO, M.O., 2009. Accessibility to and consumption of indigenous vegetables and fruits by rural households in Matungu division, western Kenya. AJFAND., 9(8): 1-14. [ Links ]

FLYMAN, M.V. & AFOLAYAN, A.J., 2006. The suitability of wild vegetables for alleviating human dietary deficiencies. S. Afr. J. Bot., 72(4): 492-497. [ Links ]

HAULE, M.J., 2016. Edible Indigenous fruits business, household income and Livelihoods of People of Songea District, Tanzania. Int J Agric Innov Res., 5(1): 2319-1473. [ Links ]

HUGHES, C., 2006. Quantitative and qualitative approaches. Warwick: University of Warwick. [ Links ]

JANSEN VAN RENSBURG, W.S., VENTER, S.L., NETSHILUVHI, T.R., VAN DEN HEEVER, E. & DE RONDE, J.A., 2004. Role of indigenous leafy vegetables in combating hunger and malnutrition. S. Afr. J. Bot., 70(1): 52-59. [ Links ]

JIBA, P., 2017. Evaluation of the socio-economic performance of smallholder irrigation schemes in Idutywa village of the Eastern Cape Province. [ Links ]

KALABA, F.K., 2007. The role of indigenous fruit trees in the rural livelihoods: a case of the Mwekera area, Copperbelt province, Zambia. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Stellenbosch: University of Stellenbosch, Western Cape, South Africa. [ Links ]

KEPE, T., 2008. Beyond the numbers: Understanding the value of vegetation to rural livelihoods in Africa. Geoforum., 39(2): 958-968. [ Links ]

LEGWAILA, G.M., MOJEREMANE, W., MADISA, M.E., MMOLOTSI, R.M. & RAMPART, M., 2011. Potential of traditional food plants in rural household food security in Botswana. J. Hortic. For., 3(6): 171-177. [ Links ]

MAJOVA, V.J., 2014. The rural-urban linkage in the use of traditional foods by peri-urban households in Nompumelelo community in East London, Eastern Cape. IAJIKS., 13(1): 164-174. [ Links ]

MAROYI, A., 2011. Potential role of traditional vegetables in household food security: A case study from Zimbabwe. Afr. J. Agric. Res., 6(26): 5720-5728. [ Links ]

MAVENGAHAMA, S., 2013. The role of indigenous vegetables to food and nutrition within selected sites in South Africa. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Stellenbosch University, Western Cape Province, South Africa. [ Links ]

MATENGE, S.T., VAN DER MERWE, D., KRUGER, A. & DE BEER, H., 2011. Utilisation of indigenous plant foods in the urban and rural communities. IAJIKS., 10(1): 17-37. [ Links ]

MITHÖFER, D., WAIBEL, H. & AKINNIFESI, F.K., 2006. The role of food from natural resources in reducing vulnerability to poverty: a case study from Zimbabwe. Paper presented at the 26th Conference of the International Association of Agricultural Economists (IAAE), 12-18 August, Gold Coast, Australia, 1-14. [ Links ]

MODI, M., MODI, A. & HENDRIKS, S., 2006. Potential role for wild vegetables in household food security: a preliminary case study in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. AJFAND., 6(1): 1-13. [ Links ]

MPALA, C., DLAMINI, M. & SIBANDA, P., 2015. The accessibility, utilisation and role of indigenous traditional vegetables in household food security in rural Hwange District. International Open and Distance Learning Journal., 1(3): 34-49. [ Links ]

NTULI, N.R., ZOBOLO, A.M., SIEBERT, S.J. & MADAKADZE, R.M., 2012. Traditional vegetables of northern KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: Has indigenous knowledge expanded the menu?. Afr. J. Agric. Res., 7(45): 6027-6034. [ Links ]

OLADELE, O.I., 2011. Contribution of indigenous vegetables and fruits to poverty alleviation in Oyo State, Nigeria. J Hum Ecol., 34(1): 1-6. [ Links ]

OR TAMBO DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY., 2010. Integrated Development Plan Review 2010/2011. [Pamphlet]. Mthatha, South Africa. [ Links ]

PORT ST JOHNS LOCAL MUNICIPALITY., 2016. Integrated Development Plan Review 2016/2017. [Pamphlet]. Mthatha, South Africa. [ Links ]

SCHIPPERS, R.R., 2000. African indigenous vegetables: An overview of the cultivated species. Natural Resources Institute/ACP-EU Technical Center for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation, Chatham, UK. [ Links ]

SCHRECKENBERG, K., AWONO, A., DEGRANDE, A., MBOSSO, C., NDOYE, O. & TCHOUNDJEU, Z., 2006. Domesticating indigenous fruit trees as a contribution to poverty reduction. For. Trees Livelihoods., 16(1): 35-51. [ Links ]

SHACKLETON, C.M., 2003. The prevalence of use and value of wild edible herbs in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Sci., 99(1): 23-25. [ Links ]

SMITH, I.F. & EYZAGUIRRE, P., 2007. African leafy vegetables: Their role in the WHO's global fruit and vegetable initiative. AJFAND., 7(3): 1-17. [ Links ]

TALENI, V. & GODUKA, N., 2013. Perceptions and use of indigenous leafy vegetables (ILVs) for nutritional value: A Case study in Mantusini Community, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the International Conference on Food and Agricultural Sciences,1 -12 October, Melakaelaka, Malaysia, 1-14. [ Links ]

VAN JAARSVELD, P., FABER, M., VAN HEERDEN, I., WENHOLD, F., VAN RENSBURG, W.J. &VAN AVERBEKE, W., 2014. Nutrient content of eight African leafy vegetables and their potential contribution to dietary reference intakes. J. Food Compos. Anal., 33(1): 77-84. [ Links ]

VORSTER, H.J., VAN RENSBURG, W.S.J., STEVENS, J.B. & STEYN, G.J., 2008. The role of traditional leafy vegetables in the food security of rural households in South Africa. Paper presented at the International Symposium on Underutilized Plants for Food Security, Nutrition, Income and Sustainable Development 806, 3 -7 March, Arusha, Tanzania, 23-28. [ Links ]

VAN DER HOEVEN, M., OSEI, J., GREEFF, M., KRUGER, A., FABER, M. & SMUTS, C.M., 2013. Indigenous and traditional plants: South African parents' knowledge, perceptions and uses and their children's sensory acceptance. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine., 9(1): 61-78. [ Links ]

WEMALI, E.N.C., 2014. Contribution of cultivated African Indigenous Vegetables to agro-biodiversity conservation and community livelihood in Mumias Sugar Belt, Kenya. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Kenyatta University, Nairobi County, Kenya. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

S.S. Ntlanga

Email: samuelntlanga@gmail.com