Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Agricultural Extension

On-line version ISSN 2413-3221

Print version ISSN 0301-603X

S Afr. Jnl. Agric. Ext. vol.47 n.4 Pretoria 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2413-3221/2019/v47n4a531

ARTICLES

Farming Households' Livelihood Strategies In Ndabakazi Villages, Eastern Cape: What Are The Implications To Extension Services?

Zantsi S.I; Bester B.II

IPhD student, Department of Agricultural Economics, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa, ORCiD number: 0000-0001-9787-3913, Email: siphezantsi@yahoo.com

IIProfessor, Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension, University of Fort Hare, Alice, South Africa. E-mail: ben@benbester.co.za

ABSTRACT

Using a retrospective and circumspective approach, this paper looks at how livelihood strategies have changed during pre and post-democratic eras in rural former Transkei of the Eastern Cape, and identifies present livelihood strategies in Ndabakazi. The focus of the research was Ndabakazi, a cluster of rural villages in the former Transkei. A survey of 80 household heads was conducted using semi-structured questionnaires, complemented by focus group discussions. The findings show that farming and wage labour have been declining over time as major sources of income, while social grants have become increasingly important. Field crop cultivation has been completely abandoned and garden cultivation is declining. The overall findings show that livelihood strategies have continued to change from land based livelihoods to non-farm and later non-labour. The paper argues the importance of understanding a farm household in the perspective of household economics theory and to incorporate the diverse portfolio of livelihood strategies in farming households into the extension advisory service in order to render relevant and appropriate service.

Keywords: Cultivation, Farming rural, Livelihood, Strategies

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background: Change of rural livelihood over time

In the late 1990s, it was noticed that rural livelihoods across sub-Saharan Africa were changing, in particular by becoming more diversified (Barret, Reardon & Webb, 2001; Ellis, 1998). As such, it was reported that up to 60% of rural African households derive most of their income from non-farm sources (Bryceson, 2000). This was against the general known view that rural households derive most of their livelihood from farming.

In South Africa, the livelihoods of black1 South Africans started to change since the contact of the colonists with the natives between 1778 and 1878 (Ncapayi, 2013). This involved land dispossession and eventually turning the Africans into wage labour (Bundy, 1979). However, Africans continued to depend on land-based livelihoods, although increasingly combined with wage labour. In the Transkei, which was one of the 'Homelands' in South Africa and the largest in terms of surface area (4 426 338 ha) (Pollock, 1969), this was noticed by declining maize yields in the 1930s which was and still is the major staple crop in the area (Bembrigde, 1984; Gilimani, 2005). For example, between 1920 and 1930, Africans in the Transkei produced 640 million pounds of maize per annum. However, this fell to 490 million pounds between 1931 and 1939 (Simkins, 1981).

This decline in agricultural production amongst Africans was also noticed by the Tomlinson Commission in the 1930s. It found that most rural households in the Transkei could not support themselves solely by farming (Redding, 1993). On the one hand, agricultural production was declining. In this regard, Bembridge (1984) highlighted how maize production in the Transkei has declined throughout the decades. For example, over the period of 1918 to 1980, maize yields in the Transkei dropped by 52%. On the other hand, non-farm and non-labour such as social grants sources of income had been increasingly becoming an important source of household income2. In the late 1950s, the state's old age grants had also been increasingly becoming an important source of income for Africans (Lund, 1993). In 1958, 60% of the state funds allocated for old age pension went to Africans (van der Berg, 1997). However, the amount paid per beneficiary was very little for Africans compared to whites which was below the minimum wage. In 1993, this figure had risen to 80% in women and 77% in men (Lund, 1993).

This continued throughout the decades with Africans combining wage labour with farming (Redding, 1993). In the late 1990s, this trend was becoming worse with the economic recession in the mining industry which saw much male-migrant labour from Transkei retrenched, bearing in mind that this was the largest employer of Transkei3 male labour (Manona, 1999; Murray, 1995). This was the same period the country was approaching the new democracy.

In the post-apartheid era, in many rural areas of the former Transkei, it can be observed that cultivation of arable fields to a great extent has declined over the years while reliance on small backyard garden cultivation has become the only form of arable cultivation (Andrew & Fox, 2004; Connor & Mtwana, 2018; McAllister, 2000). In line with the decline in farming activities, Transkei households continued relying on non-farm sources of income in the early 2000s. For example, Perret et al (2000) reported that in Transkei, 53% of households depended on pensions and welfare grants for survival, while only 8% relied mainly on farming income. At a national level in general, rural households, like their urban counterparts, mainly depend on the market for their food due to their inability to produce sufficient food for subsistence (Baiphethi & Jacobs, 2009).

1.2 Research problem

The transition to the democratically elected government in South Africa has brought major changes in agrarian policies, mostly directed to black smallholder farmers (Manona, 2005). Among the policies and support was the commercialisation programmes such as the Massive Food Production Programme and food security policies such as the Siyazondla Food Security Programme. The first sought to bring all the uncultivated arable fields into production of high quality and quantity maize to supply the Eastern Cape Province, while at the same time creating emerging black commercial farmers. However, there is inadequate evidence for its success (Fischer & Hajdu, 2015; Hajdu et al, 2012). In addition, there were other policies which sought to provide basic services to the rural communities. Overall, these policies have brought positive changes in the quality of life of the majority of rural households. However, unemployment and abandonment of arable fields continue to be a challenge in rural South Africa (Aliber, 2017; De la Hey & Beinart, 2017; Shackleton & Luckert, 2015; Statistics South Africa (StatsSA), 2016). Tracking changes in livelihood strategies is one way of examining the impact of these changes. While several studies have given explanations of why arable land cultivation and declining contribution of agriculture to rural livelihoods, little attention has been paid to how this behaviour of farming households implies to agricultural extensionists, especially with a view of the household economics theory.

1.3 Justification

Why is the study of livelihood strategies important and how is it useful? It is useful because it provides critical information concerning the goals, choices and activities which matter to local communities, thus contributing to better planning and decision making by policy makers (Walker, Mitchelle & Wismer, 2001). Furthermore, it helps to identify important historical changes which have affected households as well as providing a clear indication of how households have responded or adapted to these changes.

Moreover, it allows development practitioners to take a closer look at how people interact with resources and institutions to construct a way of life. In this respect, many of the state's rural development initiatives have seen limited success, which Kleinbooi (2013) attributed to lack of knowledge on how rural households cope with everyday challenges such as poverty and food insecurity. Hajdu et al (2012) also argued about the approach to policies intended for rural households which are based on incorrect assumptions and top-down approach resulting in unintended results.

Understanding how farming rural households combine livelihood strategies and the contribution of farming is important for agricultural extensionists in numerous ways. For example, such understanding could improve the planning of advisory service, and aid in providing relevant and appropriate advice to farming households.

1.4 Objectives and structure

It is against this background that this study seeks to track the changes in rural household livelihood strategies. The objectives of this paper are threefold. The first is to describe how livelihood in rural parts of Ndabakazi, particularly the former Transkei, have changed over time. The second is to discuss the importance and the rationale of understanding the household economics theory in improving agricultural extension. The third objective is to identify livelihood strategies in Ndabakazi villages related to those of other rural Transkei to track the change over time.

2. HOUSEHOLD ECONOMICS THEORY AND ITS IMPLICATION TO AGRICULTURAL EXTENSION

The household economics theory is a branch of neoclassical economics (Mattila-Wiro, 1999). It originates from a combination of work from different scholars. The most notable contributors include Becker (1965) in his seminal work 'A theory of the allocation of time', Muth (1966) in 'Household production and consumer demand functions', Chayanov (1966) in 'The theory of peasant economy', and Lancaster (1966) in 'Change and innovation in technology of consumption'. These scholars viewed the household from the developed world perspective. Later on, Low (1986) and Ellis (1998) provided perspectives from the developing and under-developed worlds.

The main purpose of the theory is to understand the complex structure of the household resource allocation, behaviour and decision making in coping with resource scarcity (Mattila-Wiro, 1999). The theory views the household as a single economic unit which uses market goods as inputs to produce household goods in order to maximise household utility (Muth, 1966). The other important feature of the household recognised in this theory is that a household is not static, there are distinct stages within the development of the household better, known as Household Development Cycle (HDC), and as such, resource availability changes within these stages (Fortes, 1970).

Furthermore, the theory acknowledges that time is the most important resource of the household and it can be substituted for money in the form of wage employment. In addition, household members have different opportunity cost in wage labour and the members with lower opportunity cost in wage labour are left to do farming, and these include less educated and the elderly. In contrast, those with high opportunity cost in the wage labour, for example educated and young members, are sent for wage labour (Low, 1986).

How is this theory relevant to agricultural extension and why it is important to understand? Low (1988) argued that while the objective of development practitioners, including agricultural extensionists, is to improve yields, while the farm households' objective is to maximise welfare/utility. Therefore, it would seem like agricultural extensionists are interested in only one component of farm households, improving farming skills/methods and in turn production.

However, with this approach, they are likely to miss the point. There is a need to understand the whole household behaviour, resource allocation and decision making in order to render relevant and appropriate advisory services. For example, the resource availability differs in relation to the stage of the household in the HDC, therefore, understanding the farm household by extensionists can enhance the kind of advisory service rendered. Furthermore, the drivers of change in livelihood strategies can be categorised into endogenous and exogeneous (Zantsi, 2016). The first results from internal factors within the household such the stage of the household in the household development cycle, aging of household head, and death of household head or bread winner.

These factors influence how the household combines livelihood strategies to cope with these changes, therefore understanding the farm household is important for extensionists in providing relevant advisory services (Zantsi, 2016). While Christoplos (2010) as well as Davis and Terblanche (2016) support the view that agricultural extension should encourage the creation of more livelihood opportunities as a measure of risk reduction and increasing income, the household economics approach has not been widely adopted in agricultural extension research.

3. METHODOLOGY

This study was conducted in Ndabakazi villages in Butterworth in the Eastern Cape's former Transkei area to gather data on income sources, demographic information and farming activities. Within Ndabakazi, which is a complex of six villages, four villages, namely Ejojweni, Lengeni, Komkulu and Mziteni were chosen. Ndabakazi is located 10 km from Butterworth in the direction of East London. In September 2014, a sample of 80 respondents were randomly selected and interviewed for this research. This sample was equally divided amongst the four villages as 20 respondents were selected from each village.

Semi-structured questionnaires were used to collect information from household heads using the local language, IsiXhosa, to enhance the understanding of the respondents. Focus group discussions were also used to supplement the information obtained from the household survey. The groups each consisted of eight household heads as smaller groups are easier to manage and everyone has a chance to engage in the discussion. This was done by combining respondents from two villages, Komkhulu and Ejojweni. Household heads over the age of 50 years, both females and males, were selected through the help of the headmen for the group discussion.

Studies of this nature which seek to track change over time usually require time series data (Murray, 2002). However, the challenge of data on rural household production is the major challenge in South Africa (Binswanger-Mkhize, 2014). Hence, we used past data from other former Transkei rural households and compared them with the one from Ndabakazi to overlook the change of livelihood strategies before and after the democratically elected government. This approach is a combination of circumspective and retrospective approaches. Murray (2002) supports the combination of these approaches for evaluating the changes in livelihood strategies. The circumspective approach looks at livelihood strategies at the present moment, while the retrospective approach seeks to identify change prior to and post-democratic era.

The study mainly employs descriptive statistics as a major analytic technique. This encompasses the use of averages, minimums, maximums, standard deviations, range, frequency counts, percentages and charts. The descriptive analysis has been widely used in similar studies such (McDermott, 2006; Perret, 2000), hence, it was deemed appropriate for this study given the nature of our data.

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1 Demographic information

It is important to understand the farm household structure including demographic information. This is important since the decision of farm activities is influenced by the demographic feature of the household head and household structure as argued by Modiselle et al (2005) who emphasised this importance to agricultural extension.

Findings from the present study show that many household heads in Ndabakazi were pensioners, in other words, persons over the age of 60. In all four villages, many respondents fell into the 60+ age group followed by the middle category which is between the ages of 50 and 59 as well as between 40 and 49 (Table 1). The household heads' gender distribution was dominated by females (63%). Furthermore, almost half (48%) of the respondents were widows, while 40% were married and the remainder were single or divorced. The average size of the household in Ndabakazi households is five persons per household and ranged from one to eight persons. These results are typical in many rural parts of South Africa, especially for subsistence farming households and resemble those in the Household Community Survey (StatSA, 2016).

4.2 Land holding

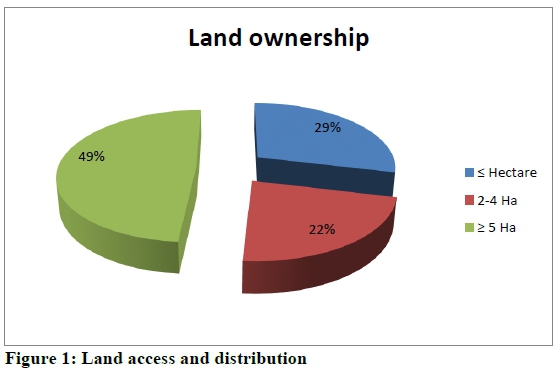

Findings from Ndabakazi show that every household has at least access to land both for arable crop production and shared grazing land. These findings are in line with those reported by Perret et al (2000) on a provincial level. She claimed that 85% of rural households in the Eastern Cape have access to arable land, while 75% have access to shared grazing land. All the surveyed households in Ndabakazi have at least access to land as shown in Figure 1.

4.3 Agricultural production

4.3.1 Crop production

Despite that the majority of respondents (49%) own more than five hectares, not even a single respondent claimed to be cultivating a field. The fields in all the villages, except for Mziteni, are fenced and it has been quite some time since they had been fenced early in the last decade. In other villages, the fence is starting to rot. In terms of garden cultivation, a large proportion (71%) of respondents cultivate gardens adjacent to their homestead. These results corroborate what the existing literature says in that rural households have not completely abandoned crop production; they have rather left field cultivation and focused on garden cultivation (Andrew & Fox, 2004). Connor and Mtwana (2018), who based their study in three areas, two in Transkei and the other in Ciskei, also found that field cultivation has been left for gardens. This suggests that this trend has cut across the Eastern Cape. However, garden cultivation is also declining in some parts of the Eastern Cape as in Ndabakazi (Shackleton & Luckert, 2015).

Maize is the most produced crop in Ndabakazi. All the respondents who claim to be producing in their gardens planted maize in the previous production season. This is in line with what Bembridge (1984) found in 1979 in the Qumbu, Emgcwe and Qamata rural areas in Transkei. Perret et al (2000) also found the same result in Tsomo, Mount Fletcher and Nyandeni in the Transkei. Later on, Gilimani (2005) also reached the same conclusion. Rural households in Ndabakazi produce an average of 150 kg of maize per year. This is equivalent to three 50 kg bags of maize. The most producing household produced 10x50 kg, while some who produce in small gardens yield only 25 kg of maize. These were the approximate quantities harvested in the 2014 production season. These may not be the exact quantities due to the nature of production in households as stated by McAllister (2000). As such, farming rural households do not formally keep records of production, however, they relate their produce in 50 kg bags and buckets. Although these figures also exclude green maize, they are far too low for a 0.5-2 ha farm.

4.3.2 Reasons for abandoning field cultivation

When asked why respondents do not cultivate their fields, a variety of reasons were cited. These include the distance from the homestead to the fields. This makes crops prone to livestock damage as the fields are near the grazing land separated by fences. Furthermore, in weeding periods, it is not easy to reach the fields. As a result, they receive lower yields since the crops are not thoroughly and completely weeded. Shackleton and Luckert (2015) also found the same reasons in Gatyana and Leyssaton in the Eastern Cape. Another common reason given was the expensiveness of tractors, which cost R3504 per hour in a field when the owner still has to hire planting services and labour for weeding. It was also mentioned that production costs are just too high for field crop production. If the homestead does not have cattle or a large family to work on the field, they have to hire everything, further limiting the turnover.

An additional reason for abandoning field production was the uneven distribution and uncertainty of rainfall. It was cited that rain falls in one month every week in such a way that they do not get a chance to prepare land and then it stops for a while. Furthermore, the occurrence of drought was mentioned to be occurring frequently. Respondents noticed the change of climate, even in temperatures. Most respondents also mentioned a lack of energy as they are older women, mentioning their health issues that they are not like their parents who were healthy throughout their lifespan.

They also mentioned the unwillingness of their children to invest in farming. Many respondents claimed that 'they do not send money for production nor do they buy livestock'. This was also noticed by Kepe and Tessaro (2014) where they found that those who are able to secure jobs in rural areas prefer to buy cars than investing in farming. Aliber (2017) also found that rural households in the former homelands spend more on hardware material for building their homesteads.

The flight of more active labour was also cited. Laziness and a lack of interest in farming was highlighted in the group discussion, particularly with regards to the younger generation. Youth are investing in fancy lifestyles, buying luxury furniture and building expensive houses. It has also been revealed that youth are very reluctant to stay in rural areas, especially those that are educated.

In summary, there are complex reasons for why people have stopped cultivating large fields and these reasons differ between households and some are interrelated. There are very few households headed by younger people or the economically active group. This can be linked to high unemployment rates. Furthermore, a lack of interest in farming among the youth was observed from the focus group discussions and that farming is failing to attract young people as an income generating activity that one may rely on. Hull (2014) also shared similar findings in one former homeland in KwaZulu-Natal, where there is a large pull of labour available, especially young people who still live with their parents, but are not interested in household agricultural activities, even in the face of limited employment opportunities.

4.3.3 Livestock production

The main livestock kept by households in Ndabakazi includes goats (46%) and poultry (64%). The most commonly kept stock is indigenous free range chickens (64%), followed by goats (46%), pigs (38%), cattle (36%), and sheep (29%). In Komkhulu village, none of the respondents owned sheep. The widespread farming of chickens may be due to their easy accessibility as they are relatively cheap and the lending is more common in chickens than in any other livestock types. Most of the households claimed that fewer households own livestock now as compared to the past. The average household livestock holdings are presented in Table 2.

Chickens and small stock (goats and sheep) seemed to be more compared to cattle. With sheep having an average of 16.25, goats 10, and cattle 5. The small number of cattle holding also has an effect on crop production as cattle are used to plough the land and for planting. As a result, it was mentioned that very few households use draft power to till the land. With the high cost of production that was previously highlighted, the use of draft power animals can reduce the cost of production making subsistence production worthwhile and increasing food supply. In this respect, animals such as horses and donkeys who have longer lifespan and adapt well in drought and to diseases can play a vital role. Extension services provided by the state should prioritise animal traction for subsistence farmers.

Furthermore, 11% of the households kept none of the mentioned stock types. They pointed out a number of reasons for this. These include the cost of keeping livestock, namely that vaccines are expensive, diseases are prominent, and it is difficult to succeed without them in keeping stock. Another reason pointed out regards livestock herders. Boys attend school now on a regular basis, and in other households that are headed by women, there may be no boys. This means there will be no one to look after stock. The cost of hiring a shepherd/ herder is quite high, ranging between R1000 and R1500. Also emphasised was the loss of Ubuntu amongst the community and working together where a child is raised by a community in such a way that a neighbour's child can be asked to do something, as it used to be in the past.

4.4 Income sources in Ndabakazi

4.4.1 Main income source

Rural households in South Africa, as a way of coping with risk and uncertainty of food prices, rainfall and diseases, rely on a portfolio of income sources.

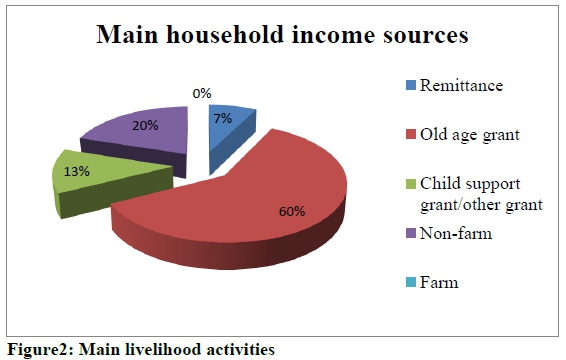

Figure 2 presents the main sources of income for households in Ndabakazi. The main livelihood strategies were identified based on the activity that contributes the most to the household income. Social grants are the main source of income in Ndabakazi. Old age grants were the dominant livelihood strategies followed by non-farm income, child support grants and other forms of social grants, except for old age grants, remittances and farm income. The larger proportion of old age grants as a main source of income can be justified by the age of the respondents. The non-farm sources of income include government employment such as educators, police officers, and nurses. Self-employment and petty trading are also part of this category. Child support grants accounted for 13%. There were very few respondents (7%) who depended mainly on remittances. No respondents claimed to be dependent mainly on farming activities, hence the 0% as shown in Figure 2.

These results paints a picture that farm households in Ndabakazi, as is the case in most rural parts of South Africa, are headed by pensioners, with farming contributing very little to household income as argued by Baiphethi and Jacobs (2009). This also links with the HDC in that towards the aging of the parental group, resources become scarce and farming activities decline. Furthermore, Low (1986) ascribed the decline of food production in rural farm households to the fact that farming is left for the elderly, mostly women, since the young members have comparative advantages in wage labour in the cities. Moreover, the majority of households are headed by females who have other household chores other than farming. This may be taken to imply that they have less time for farming, hence the little contribution of farming as a livelihood activity.

While many development policies (e.g. Food Security Policy, Land Reform, etc.) are designed with the assumption that since rural households have at least land available to them and there are very limited opportunities for non-farm employment, they will or should be focusing on farming. Unfortunately, that does not seem to be happening successfully, partly because farm households strive to maximise welfare/ utility and therefore will always choose activities which maximise utility at less efforts as Low (1986) argued.

4.4.2 Combination of income sources

It is rare to find households depending solely on one income source (Barret et al, 2001; Manona, 1999; Shackleton & Luckert, 2015). Figure 3 depicts the combination of livelihood strategies pursued by households in Ndabakazi.

When grouping the main three contributing activities to household livelihoods, Old Age Grants (OAG), Child Support Grants (CSG), and farming were the most combined activities by most households (Figure 3). This finding corroborates with that of Perret et al (2000) in Xume, Tsomo, and Mount Fletcher, which are also Transkei rural areas. Following this group was the child support grant plus remittances and farming. Remittances plus child support grants and farming were the least combined activities as there were only a few respondents who receive remittances on a regular basis. Farming has been the smallest contributor in all the combinations.

This suggests that the households of Ndabakazi depend mainly on a combination of social grants and farming activities. This finding is in line with those of Shackleton and Luckert (2015) and contradict those of McDermott (2006) in Sehlabethe Lesotho and Richtersveld in the Northen Cape Province that rural households have not changed from relying on farming, but rather there is a change in relative importance of the farming activities.

5. SYNTHESIS AND CONCLUSION

This paper sought to achieve the following three objectives. The first was to describe how livelihood strategies have changed in pre and post-democratic eras in rural Transkei. Secondly, to identify livelihood strategies of Ndabakazi rural households and observe the change in relation to the change described in Transkei. The third objective was to discuss the importance and the rationale of understanding the Household Economics Theory in improving agricultural extension.

Farming as a source of income in rural Transkei has been declining throughout the decades. In the 1980s, evidence form Qumbu shows that it contributed only 8% to household income. While in the late 1990s, evidence from the whole of the Eastern Cape Province showed that it had declined to 4%. Current findings from Ndabakazi show that the figure has fallen to less than 1%. Wage labour contribution to household income has also been declining; in the 1980s its share was 41, 4%, while in the late 1990s it had fallen to 26%. The current findings from Ndabakazi show that it has further fallen to 20%. This can be attributed to high unemployment rates which, from the 1996 census and central statistics as cited by Perret et al (2000), was 48, 5%. Recent reports from Statistics South Africa also show a high unemployment rate of 28, 5% in the Eastern Cape, while in Mnquma Local Municipality where the study areas are, it is 44, 2% according to the 2011 census.

In contrast, social grants have become a significant rural income source in the Transkei. In the 1980s, the share of social grants to the rural household income was 17,2%, while in the late 1990s, it hiked to 40%. Current findings from Ndabakazi shows that social grant income accounts for more than 70% of rural household income now. It has also been observed that investment of the households have changed over time from investing in livestock to a fancy lifestyle of modern houses and furniture driven by the younger generation.

In conclusion, livelihood strategies in rural Transkei have continued to change from land-based to non-farm and later to non-labour since the contact of Africans with the colonists up to the democratically elected government. Social grants, mainly old age grants and child support grants are the major sources of income in rural Transkei and in Ndabakazi villages. Although there have been a number of support programmes implemented with limited success in the rural areas of the former Transkei such as the Comprehensive Agricultural Support Programme, the Siyazondla Food Security Programme, and the Massive Food Production Programme, there is still high unemployment (Fischer & Hajdu, 2015; Kubheka, 2015; Nilsson, 2008; StatsSA, 2016). Rural households continue to move away from the land-based livelihood. The Household Economics Theory provides a good lens in understanding farm households' behaviour, resource allocation and decision making, and this is important for agricultural extensionists in providing relevant and effective advisory services.

6. IMPLICATIONS FOR AGRICULTURAL EXTENSION

Results from this case study confirm the ongoing declining contribution of farming as an income source and income diversification in rural farming households. This implies that agricultural extension advisory services should incorporate the goals of farming rural households and caution against being biased towards encouraging and focusing solely on improving farming practices, but also encourage an effective combination of livelihood that would improve the welfare of farming households. This can be achieved through a holistic farm household economic perspective and understanding of the goals of farming households. Among other objectives, the objective of agricultural extensionists should be to strive to help farm households through advisory services on how to combine their livelihood activities to maximise utility, given certain farm household characteristics.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the financial assistance of the Levenstain Family Bursary Trust and the Govern Mbeki Research and Development Centre in data collection. The authors would also like to thank reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions.

REFERENCES

ALIBER, M., 2017. The former Transkei and Ciskei homelands are still poor, but is there an emerging dynamism? Available from: http://www.econ3x3.org/sites/default/files/articles/Aliber%202017%20Rural%20economic%20change%20-%20FINAL.pdf [ Links ]

ANDREW, M. & FOX, R.C., 2004. Undercultivation and intensification in the Transkei: A case study of historical change in the use of arable land in Nompa, Shixini. Dev. South. Afr., 21(4):687-706. [ Links ]

BAIPHETHI, M.N. & JACOBS, P.T., 2009. The contribution of subsistence farming to food security in South Africa. Agrekon, 48(4):459-482. [ Links ]

BARRET, C.B., REARDON, T. & WEBB, P., 2001. Nonfarm income diversification and household livelihood strategies in rural Africa: Concepts, dynamics, and policy implications. Food Policy, 26(4):315-331. [ Links ]

BECKER, G.S., 1965. A theory of the allocation of time. Econ. J., 75(299):493-517. [ Links ]

BEMBRIDGE, T.J., 1984. A systems approach study of agricultural development problems in Transkei. PhD Thesis, University of Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

BINSWANGER-MKHIZE, H.P., 2014. From failure to success in South African land reform. Afr. J. Agr. Resour. Econ., 9(4):253-269. [ Links ]

BUNDY, C., 1979. The rise andfall of the South African peasantry. California: University of California Press. [ Links ]

BRYCESON, D.F., 2000. Rural Africa at the crossroads: Livelihood practices and policies. London: Overseas Development Institute. [ Links ]

CHAYANOV, A.C., 1966. The theory of peasant economy. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [ Links ]

CHRISTOPLOS, I., 2010. Mobilizing the potential of rural and agricultural extension. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organisation. [ Links ]

CONNOR, T. & MTWANA, N., 2018. Vestige garden production and deagrarianization in three villages in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. S. Afr. Geogr. J., 100(1):82-103. [ Links ]

DAVIS, K.E. & TERBLANCHE, S.E., 2016. Challenges facing the agricultural extension landscape in South Africa, Quo Vadis? S. Afr. J. Agric. Ext., 44(2):231-247. [ Links ]

DE LA HEY, M. & BEINART, W., 2017. Why have South African smallholders largely abandoned arable production in fields? A case study. J. South. Afr. Stud., 43(4):753-770. [ Links ]

ELLIS, F., 1998. Household strategies and rural livelihood diversification. J. Dev. Stud., 35(1):1-38. [ Links ]

FISCHER, K. & HAJDU, F., 2015. Does raising maize yields lead to poverty reduction? A case study of the Massive Food Production Programme in South Africa. Land Use Policy, 46:304-313. [ Links ]

FORTES, M., 1970. Time and social structure and other essays. London: Athlone Press. [ Links ]

GILIMANI, B.M., 2005. The economic contribution of home production for home consumption for South African agriculture. Masters Thesis, University of Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

HAJDU, F., JACOBSON, K., SALOMONSSON, L. & FRIMAN, E., 2012. But tractors can't fly... A transdisciplinary analysis of neoliberal agricultural development intervention in South Africa. Epiphany, 6(1):24-61. [ Links ]

HULL, E., 2014. The social dynamics of labour shortage in South African small-scale agriculture. World Dev., 59(1):451-460. [ Links ]

KEPE, T. & TESSARO, D., 2014. Trading off: Rural food security and land rights in South Africa. Land Use Policy, 36:267-274. [ Links ]

KLEINBOOI, K., 2013. Land reform, tradition and securing land for women in Namaqualand. In In the shadow of policy. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. [ Links ]

KUBHEKA, B.C., 2015. Impact assessment of the Siyazondla Homestead Food Production Programme in improving household food security of selected households in the Amathole District, Eastern Cape. Masters Thesis, University of KwaZulu-Natal. [ Links ]

LANCASTER, K., 1966. Change and innovation in the technology of consumption. Am. Econ. Rev., 46(2):14-23. [ Links ]

LOW, A., 1986. Agricultural development in southern Africa, farming household economics and the food crisis. London: James Currey. [ Links ]

LOW, A., 1988. Farm household-economics and the design and impact of biological research in Southern Africa. Agric. Admin.& Extension, 29(1):25-34. [ Links ]

LUND, F., 1993. States social benefits in South Africa. Int. Soc. Secur. Rev., 46(1):5-25. [ Links ]

MANONA, C., 1999. De-agrarianisation and the urbanization of a rural economy: Agrarian patterns in Melani village in the Eastern Cape. ASC Working Paper. Rhodes University, South Africa. [ Links ]

MANONA, S.S., 2005. Smallholder agriculture as Local Economic Development (LED) strategy in rural South Africa: Exploring prospects in Pondoland, Eastern Cape. Masters Thesis, University of the Western Cape. [ Links ]

MATTILA-WIRO, P., 1999. Economic theories of the household: A critical review. Helsinki: UNU-WIDER. [ Links ]

MCALLISTER, P.A., 2000. Maize yields in the Transkei: How productive is subsistence cultivation? Occasional Paper No. 14. PLAAS. Cape Town, South Africa. [ Links ]

MCDERMOTT, L., 2006. Contrasting livelihoods in the upper and lower Garriep River basin: A study of livelihood change and household development. Masters Thesis, Rhodes University. [ Links ]

MODISELLE, S., VAN ROOYEN, C.J., LAURENT, C., MAKHURA, M.T., ANSEEUW, W. & CASTERNS, J., 2005. Towards describing small-scale agriculture: An analysis of diversity and the impact thereof in the Lielifontein area (Northern Cape, South Africa). S. Afr. J. Agric. Ext., 34(2):303-317. [ Links ]

MOLL, T., 1984. A mixed and threadbare bag: Employment, incomes and poverty in Lower Roza, Qumbu, Transkei. Working Paper No. 4. University of Natal, South Africa. [ Links ]

MURRAY, C., 1995. Structural unemployment, small towns and agrarian change in South Africa. Afr. Aff., 94(374):2-22. [ Links ]

MURRAY, C., 2002. Transcending boundaries of time and space. J. South. Afr. Stud., 28(3):489-509. [ Links ]

MUTH, R.F., 1966. Household production and consumer demand functions. Econometrica, 34(3):699-704. [ Links ]

NCAPAYI, F., 2013. Land and changing social relations in South Africa's former homeland reserve: The case of Luphaphasi in Sakhisizwe local Municipality, Eastern Cape. PhD Thesis, University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

NILSSON, A., 2008. The baby of the government - A case study of the implementation of the Massive Food Production Programme and genetically modified maize into smallholder farming in rural South Africa. PhD Thesis, Swedish University. [ Links ]

PERRET, S., 2000. Livelihood strategies in rural Transkei (Eastern Cape Province): How does wool production fit in? Working Paper 2002-20. University of Pretoria, South Africa. [ Links ]

PERRET, S.R., CARSTENS, J., RANDELA, R. & MOYO, S., 2000. Activity systems and livelihoods in the Eastern Cape Province rural areas (Transkei): Household typologies as a socio-economic contribution to the land care project. Working Paper 2000-07. University of Pretoria, South Africa. [ Links ]

POLLOCK, N., 1969. The Transkei: An economic backwater? Afr. Aff., 68(272):250-256. [ Links ]

REDDING, S., 1993. Peasants and the creation of an African middle class in Umtata, 18801950. Int. J. Afr. Hist. Stud., 126(3):513-539. [ Links ]

STATISTICS SOUTH AFRICA (StatsSA), 2016. Community household survey. Available from: www.statssa.gov.za [ Links ]

SHACKLETON, S. & LUCKERT, M., 2015. Changing livelihoods and landscapes in the rural Eastern Cape, South Africa: Past influences and future trajectories. Land Use Policy, 4(4):1060-1089. [ Links ]

SIMKINS, C., 1981. Agricultural production in the African reserves of South Africa, 19181969. J. South. Afr. Stud., 7(2):256-283. [ Links ]

VAN DER BERG, S., 1997. South African social security under apartheid and beyond. Dev. South. Afr., 14(4):481-503. [ Links ]

WALKER, J., MITCHELLE, B. & WISMER, B., 2001. Livelihood strategy approach to community-based planning and assessment: A case study of Molas, Indonesia. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais., 19(4):297-309. [ Links ]

ZANTSI, S., 2016. The influence of aspiration in changing livelihood strategies in rural households of Ndabakazi villages in the Eastern Cape. MSc Thesis, University of Fort Hare. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

S. Zantsi

Email: siphezantsi@yahoo.com

1 Blacks, black South Africans, Africans and natives are used interchangeable in this article.

2 In Transkei, in the 1980s, the share of social grant to the rural household income was 17,.2% (Moll, 1984), while in the late 1990s, it hiked to 40% (Perret et at, 2000).

3 This is now the former Transkei after 1994. All homelands were incorporated into the nine provinces of South Africa.

4 2014 Rand value when the data was collected; this might have risen now.