Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Agricultural Extension

On-line version ISSN 2413-3221

Print version ISSN 0301-603X

S Afr. Jnl. Agric. Ext. vol.38 n.1 Pretoria Jan. 2009

Job burnout and coping strategies among extension agents in south western Nigeria

O.I. Oladele

Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension, North West University, Mafikeng Campus. South Africa oladimeji.oladele@nwu.ac.za

ABSTRACT

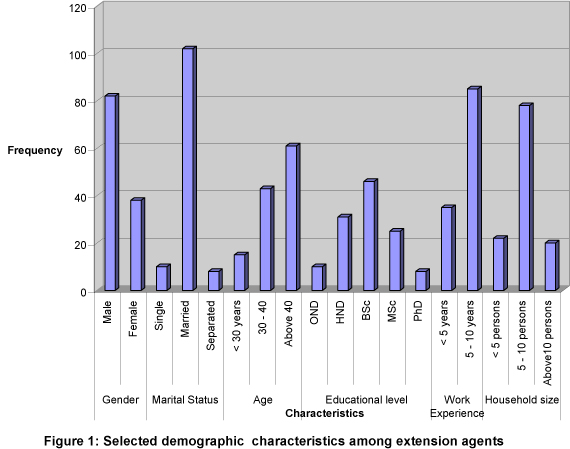

The need to maintain a non-mineral dependent economy and daunting food import bills have been the drive for the provision of extension services, which is dependent on motivated extension work force.. Extension personnel will not stay motivated under circumstances where the risk of job burnout is high. A simple random technique was used to select 120 extension agents from 328. Data were collected with a structured questionnaire (reliability coefficient of 0.85) and were analyzed with frequency counts, percentages one-way analysis of variance and multiple regressions. The result shows that 68% of the agents are males 85% married; 50% are above 40 years and 66% have at least a BSc degree. Burnout symptoms manifest mostly as depression (48%), insomnia (40%), headaches (43%), and weight loss (44%). Popular coping strategies are keeping positive attitude at all times, setting self-realistic goals, and maintaining healthy relationship with co-workers. A significant difference exists in burnout symptoms experienced across the states (F = 5.71, df 3117 p < 0.05). Significant determinants are age (t = 3.61), Number of children (t = 4.36), and coping strategy (t = -4.71).The study recommends that extension agents should be young, dynamic, maintain manageable family size and be exposed to different techniques to cope with burnout symptoms.

1. INTRODUCTION

In many developing countries agricultural development is hinged on extension services by helping farmers to identify and link with research on their production problems. They also provide awareness on opportunities for improvement of farm yields leading to increased income and better standard of living (Van den Ban and Hawkins 1998) through the dissemination of information on agricultural technologies and improve practices to farm families.

Long and Sworzel (2007) noted that the mission of extension services is to provide research based information, educational programs and technology focused on the issues and needs of the people, enabling them to make informed decisions about their economic, social and cultural well-being. A major factor in the success of achieving this role is information and understanding of the conditions and characters of the target population as well as the skills to act on that knowledge. Poor financing of extension programmes has been a long standing problem facing the services (Adams 1984). This has resulted in problems with mobility and supplies and extension agents waiting to the point of demoralization before receiving supplies to work. In 1997, Nigeria had 6,563 extension agents with an extension agent farmer's ratio of 1:1615. These are in sharp contrast to 1: 252 and 1: 500 found in Japan and South Korea respectively. (Agabmu 1998). At the end of 2003, the ratio of extension agents to farmers which is prevalent in developing country had resulted in work overload. The findings of Santucci (2002) corroborate that of Agbamu (1998) that most Nigerian farmers depend on public extension workers for information. Presently, the ratio is 1:2100 in Edo State, 1:2131in Ogun State, 1:16917 in Oyo State, 1:1496 in Lagos State (Adebowale, Ogunbode, and Salawu 2006). These ratios suggest that extension agent's hours of work, per day and the overall workload would be very huge.

There is an enormous demand on extension agents them by the clientele and the institutions they serve due to interaction with clientele in various roles and at the same time responding to administrative duties within the organizational setting. These demands could predispose them to frustrations and stress (Kutilek, Conklin, and Gunderson 2002). These processes can easily lead to burnout among extension agents which is defined as extreme tiredness usually caused by working too much. Furthermore, it is to cause someone to lose most of their energy and enthusiasm for work because of having worked too much for too long periods under stress. Burnout is a state of overwhelm, emotional restlessness and depression due to prolonged levels of high stress usually related to excessive workplace or life style demands and a general imbalance in life style. Burnout refers to prolonged response to chronic emotional and interpersonal stressors on the job, and is defined in three dimensions of exhaustion, cynicism and inefficacy (Maslach, et al 2001). Physical and emotional exhaustions could precipitate cynicism, which in turn have the potential to reduce efficiency at work. These interrelated dimensions affect productivity and overall well-being of employees. There is depletion of self by exhausting one's physical and mental resources. It is a process that begins with excessive and prolonged level of job stress that produces strain in the employee. Either the workers learn to defensively cope with the job or it may cause a syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and reduced personal accomplishment (George and Jones 1999).

Burnout can manifest as physical, psychological and behavioural changes in body function, attitudes and actions towards others (Igodan and Newcomb 1986). Fetsch et al (1997) defined burnout as a syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment that can occur among individuals who do people- related work. According to Karen (2005) it is not due to dislike of the job as an extension agent, but overwork.

Riggs and Beus (1993) reported that agents need to recognize the various factors that determine job satisfaction and understand that a weakness in those factors increases stress, thereby decreasing job satisfaction. Agents enjoy their work more when they exercise their ability to analyze situation and re-programme their initial response to stress as being less than critical. Adesope and Agumagu (2003) noted that work experience is significantly correlated with job stress among extension agents in Akwa Ibom State agricultural development programme, Nigeria. In Ohio, Igodan and Newcomb (1986) reported that agents who were satisfied with their jobs did not have much of a problem with burnout, but as job satisfaction decreases, burnout increased. In Kentucky, Fetsch et al (1984) noted that extension professionals had higher mean stress level score than normal adult and that prolonged exposure to such high stress levels predisposes them to physiological and emotional stress-related problems. In Colorado, the major differences in stress, depression and life satisfaction levels for extension agents were found associated not with occupation, gender or job site but rather with number of years of service and marital status (Kennington 1988). Asiabaka, (1991) noted that job, environmental, personal and family related stress factors affect block extension supervisors in Imo state agricultural development project in Nigeria.

Despite the foregoing, extension personal have developed adaptive strategies as they continue on the job. Coping strategies refer to specific efforts, both behavioural and psychological that people employ to master, tolerate, reduce or minimize stressful events (Folkman and Lazarus 1980). These are skills developed through experience for life situations. Ultimately, the extent to which stress is experienced and whether it is positive or negative depend on how people cope. George and Jones (1999) reported that there are problem-focused and emotion-focussed coping strategies. Problem focused coping strategy is the steps workers take to deal with and act on source of stress. Emotion focused strategy is the steps worker take to deal with and control their stressful feelings and emotions.

The working conditions of extension agents in agricultural development programme within Nigeria have been subject of research for so many years by different authors (Oladele 2004, Banmeke and Ajayi 2005, Adekunle 1998 and Akinsorotan 2007). In Nigeria it has been observed that there is low job satisfaction among extension agents which can lead to burnout. There is concern about the rate of extension agents' resignations from the service as the most frequently cited reasons for resigning is the absorptiveness of the job. Highly absorptive jobs require a great amount of time, commitment and involvement (Kanter 1977). Ezell (2003) reported that the occurrence of job stress among Tennessee extension employees increased turnover. Despite all the findings from above authors that extension agents were experiencing high level of job dissatisfaction due to the prevailing work conditions in the Agricultural Development Programme (ADP), a large number of extension agents still continue at work. This continuity suggests that such extension agents employ some means to cope with the life and work. The objective of this study was to investigate burnout and coping strategies among extension agents in south western Nigeria.

2. METHODOLOGY

The study was carried out in south western Nigeria, which consist of eight states namely Delta, Edo, Lagos, Ogun, Osun, Ondo, Ekiti, and Oyo States. The area lies between latitudes 4 and 14 south and longitude 2 and 8 east; they collectively cover 114,271km2 which is approximately 12% of Nigeria's total area. Agriculture sector forms the base of the overall development thrusts of the area, with farming as the main occupation of the people in the area. The high concentration of extension agents in this part of Nigeria necessitated the choice for the study. The population of the study includes all extension agents in south western Nigeria. Four out of eight states were randomly selected namely Lagos, Ogun, Oyo and Edo States with 90, 122, 60 and 56 extension agents respectively. A simple random sampling technique was used to select 30 extension agents from each of the states to give a sample size of 120 extension agents. Data were collected through the use of structured questionnaire that had been subjected to face validity and reliability test using split-half technique with a coefficient of 0.85. The variables of the study include demographic characteristics where agents indicated the categories they belong. Job burnout was operationalized on a 3-point scale of all assignments (3 points), some assignments (2 points) and few assignments (1 point). The scale consisted of 30 burnout symptoms from which respondents were to indicate the ones they experience on their assignments in the work place. Coping strategy was measured on a 2 point scale of every season (2points) or every other season (1 point) and consisted of 28 statements on strategies. Data collected were subjected to frequency counts, percentages, one way analysis of variance and multiple regression analysis.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Results on the demographic characteristics of extension agents are presented in Figure 1, which shows that 68 percent of the agents are males and implies that there is dominance of males in the extension delivery profession. Also, 85 percent are married, a factor that may be attributed with the cultural belief in the study area that married individuals are responsible people. The marital status also has implication for the combination of family and work responsibilities. About 50 percent of the agents are above 40 years of age which represent and energetic work force that requires motivation. About 66 percent of the agents had at least BSc as their educational qualification, a situation that would enhance the understanding of activities to be done and high competence. However the educational qualification can be explore negatively if work conditions in the extension delivery are not favourably comparable to those in other sector. Seventy percent of the agents have working experience of between five to ten years with 65 percent having a household size of five to ten persons.

Table 1 presents the results of burnout symptoms experienced by extension agents in south western Nigeria. The most experienced burnout symptoms are depression (48%), insomnia (40%), headaches (43%), and weight loss or gain (44 %). Others are: Inability to make decision (41%), increased worry (41%) and low job performance (34%). While four are physical symptoms, two are psychological while the last one is behavioural. The percentages of incidence of these symptoms are between 34 and 48 which are sufficiently high enough for attention by extension mangers and policy makers. Due to the consequences of burnout symptoms, it is important now that provisions are made to reduce the existence of burnout among the extension work force before a total collapse is experienced. The physical symptoms that could be attributed to wide area of coverage by each extension agent, the distance between the locations of meeting with farmers and poor mobility facilities for extension agents to reach farmers. The nature of the organizational setting of the Agricultural Development Programme (ADP) would have been responsible for the psychological symptoms such that extension agents are located at the end of the chain of command and are to obey instructions even when the superiors are not familiar with the reality of the situations extension agents face among farmers or in their areas of operations. In terms of behavioural symptoms, the most acclaimed consequence (low job performance) of job burnout among authors has set in among extension agents. On the other hand, the least experienced job burnout symptoms among extension agents are shortness of breath (13 %), high alcohol use (7 %) and accident proneness (20 %)

As shown in Table 2, prominent strategies among extension agents are "I develop a realistic picture of myself (72%), "I keep a positive attitude at all times" (68%), "I set realistic goals for myself (53%), "I don't easily get worked up" (59%), "I take time to rest when necessary" (67%), "I maintain a healthy relationship with co-worker(s)" (67%), "I retain hope" (62%) and "I am highly receptive to new ideas" (63%). These are in response to physical, psychological and behavioural symptoms. The least used coping strategies are "I prioritize on how best to accomplish tasks through time management" (67.50%) and "I am into other ventures to supplement my pay" (69.17%).

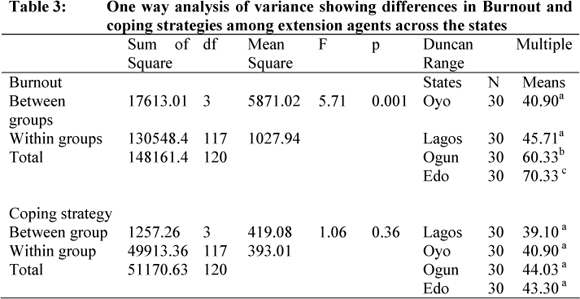

To compare the differences among the states' Burnout and coping strategies, One Way Analysis of Variance was used and the result presented in Table 3. No significant difference exists among extension agents in the different states for coping strategies. It therefore pre supposes that the strategies used across the state are the same. However, a significance difference exits in burnout symptoms experienced by extension agents across the states (F = 5.71, df 3117 p < 0.05). The mean score are Oyo = 40.90, Lagos = 45.71, Ogun= 60.33, and Edo = 70.33. Extension agents from Edo state had the highest mean while Oyo has the lowest. The administrative setting of the ADP's would have been responsible for the trend of the mean scores recorded.

The result of the multiple regression analysis of relationships between demographic characteristics and job burnout symptoms experienced by extension agents is presented in Table 4. The independent variables are significantly related to the job burnout experienced by extension agents with F value of 3.67, p < 0.05. Also the R value of 0.55 shows that there is a strong correlation between the independent variables and the job burnout and the demographic characteristics and coping strategies were able to predict 31 percent of the variation in job burnout experienced by extension agents. Significant determinants are age (t = 3.61), Number of children (t = 4.36), and coping strategy (t = -4.71). It implies that the older the extension agents are, the higher the number of children in agents' households, the more the job burnout experiences they will have. However, as the number of coping strategies increases, job burnout decreases. It is important to ensure that extension agents are young and dynamic and maintain manageable family size. Also, provision for domestic support or allowance should be made for extension agents so that the incidence of role conflicts between office and work could be minimized. It is equally important that extension agents are exposed to different techniques to cope with burnout symptoms as this will help them to be able to mange themselves better.

4. CONCLUSION

The study has shown that there is high incidence of job burnout among extension workers in south western Nigeria. The burnout symptoms have highlighted areas of self management training needs for the extension agents. There is also the dominance of males in the extension delivery profession and agents are married. The educational level of many the agents are high and with long years of working experience, above 40 years of age and had served between five and ten years. Prominent job burnout symptoms are depression, insomnia, headaches, weight loss or gain, inability to make decision, increased worry and low job performance. Popular strategies among extension agents are development of a realistic picture of one self, keeping positive attitude at all times, setting self realistic goals, never getting easily worked up, taking time to rest when necessary, maintaining healthy relationship with co-workers, retaining hope and being highly receptive to new ideas. Significant determinants of job burnout among extension agents are age, number of children, and coping strategy. The study therefore recommends that policy makers should ensure that extension agents are young and dynamic and maintain manageable family size. Also, provision for domestic support or allowance should be made for extension agents so that the incidence of role conflicts between office and work could be minimized. It is equally important that extension agents are exposed to different techniques to cope with burnout symptoms as this will help them to be able to mange themselves better.

REFERENCES

ADAMS, M. E., 1984. Agricultural Extension in Developing Countries second Edition, Longman Group ltd, Essex, Pp 3-4 [ Links ]

ADEBOWALE, E.A., OGUNBODE, B.A. & SALAWU, R.A. (Eds), 2006. "Farming Systems Research and Extension". Proceedings of the 13th Annual Southwest Zonal OFAR and Extension Workshop. Institute of Agricultural Research and Training Obafemi Awolowo University. Moor Plantation, Ibadan. Pp180. [ Links ]

ADEKUNLE, O.A. & OLADELE, O.I., 1998. Job satisfaction among Female Extension Agents in Oyo, Ogun, Osun and Ondo State ADP's in Nigeria's. [ Links ]

AGBAMU, J.U., 1998. "A study on Agricultural Research-Extension linkages: with focus on Nigeria and Japan", Ph.D Thesis, Tokyo University of Agriculture, Tokyo, Pp 194-195 [ Links ]

AGBAMU, J.U., 2005. "Problems and Prospects of Agricultural Extension in Developing countries" Agricultural Extension society of Nigeria (AESON) p.161. [ Links ]

AKINSOROTAN, A.O., 2007. "Elements of Agricultural Extension Administration ". Bountry Press Limited, Pp 82-86. [ Links ]

BANMEKE, T. & AJAYI, A., 2005. Job satisfaction of Extension workers in Edo State. Agricultural Development Programme (EDADP), Nigeria. Int. Journal of Agric Rural. Dev 6: 202-287. [ Links ]

ENSLE, K. M., 2005. Burnout: How does extension balance job and family? Journal of Extension [ Links ][on-line]. 43(3) available at http://www.joeorg/joe/2005june/a5.shtml

FOLKMAN, S. & LAZARUS, R.S, 1980. An analysis of coping in a middle aged community sample. Journal of Health 2nd Social behaviour, P.21, 219-239. [ Links ]

GEORGE, J.M. & JONES, G.R., 1999. Understanding and Managing organizational Behavior. 2nd(Ed). Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc. pp295-31. [ Links ]

IGODAN, O.C, & NEWCOMB, L.H., 1986. Are you experiencing burnout? Journal of extension [on-line], [ Links ] 24(1) Available at: ''joe.org/joe/1986spring/al.html

KUTILEK, L,M, CONKLIN, N.L & GUNDERSON G. 2002. Investing in the future: addressing work/life issues of employees. Journal of extension (online ) 40 (1): available at http://www.joe.org/joe/2002february/a6html [ Links ]

MASLACH, C., SCHAUFELI, W.B., & LEITER, M.P., 2001. "Job burnout", Annual Review of Psychology, Vol. 52 No.1, pp.397-422. [ Links ]

OLADELE O.I. 2004. Effect of World Bank Loan withdrawal on the performance of Agricultural Extension in Nigeria Nordic. Journal of Africa Studies 13(2) 141-125. [ Links ]

RIGGS, K. & BUES, K., 1993. "Job Satisfaction in Extension". Journal of Extension, Vol. 31. No. 2 http://www.joe.org/joe/1993summer/a5.html. Accessedin February, 2009. [ Links ]

VAN DEN BAN, A.W. & HAWKINS, H.S., 1998. Agricultural Extension, second Edition, Blackwell Science Publication Oxford pp 267-268 [ Links ]