Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Agricultural Extension

On-line version ISSN 2413-3221

Print version ISSN 0301-603X

S Afr. Jnl. Agric. Ext. vol.37 n.1 Pretoria Jan. 2008

Women and leadership positions in the Malian Ministry of Agriculture: Constraints and challenges

M. Akeredolu

SAFE/IPR/IFRA, University of Mali, Mali. email: obonkus2@yahoo.co.uk. Tel: 002236452372

ABSTRACT

This study is based on a comparative analysis of female and male employees in leadership positions in the Malian Ministry of Agriculture. Special emphasis is placed on the obstacles and challenges limiting women attaining leadership positions within the Ministry.

It provides insights into gender and cultural bias within the Ministry. Leadership positions within the Ministry of Agriculture in Mali are male-dominated considering the low number of females in management ranks, and little is done to help women fit into these positions. This is especially true when female officials perceive that they make more contributions such as focusing on process rather than just results, paying attention to details, showing compassion and care in decision making, expressing willingness to "go the extra mile," being sensitive in human relations, and offering fresh perspective to administrative problems. However, the male officers claimed to be more committed than their female counterparts.

Key Words: Leadership positions, agricultural development, gender, culture.

1. INTRODUCTION

Agricultural and rural development progress in sub-Saharan countries of Africa varies from one area to another, depending on factors such as natural resource endowments, history, political stability, and cultural and socio-economic environment. The greatest challenge to Africa's agricultural sector is to increase production and the value of agricultural products. As the amount of arable land available is limited, such an increase will have to be based both on intensification of farming as well as on adding value to products. Women are at the forefront of meeting this challenge, as agricultural production is primarily their domain, accounting for 70% of agricultural labour, responsible for 60% of agricultural production and 80% of food production in Africa (Kabeer, 1994). It is important to note the participation of women and the role they play at national level as leaders and decision makers in the agricultural sector.

The role of women in agricultural and rural development is surrounded by myth and misunderstanding. Although significant changes have occurred in the agricultural sector over the past 20 years, especially in the role played by women and in the understanding of this role the continued absence of appropriate policy and programme strategies on women means that their contribution to agriculture remains relatively invisible. This persistent failure to recognise and account for the value of women's knowledge and labour in the agricultural sphere, and to integrate the reality of women's situation into development policies and programmes, is vital in the global economic development environment.

Invisibility is one of the numerous obstacles preventing women from realising their full potential. Many of these obstacles arise from the cultural and social constraints that perpetuate women's marginalized situation and are kept in place, rather than remedying the situation through 'adjustments', or fundamental shift, to remove the veils of blindness. According to labour market theories, the value of certain skills strongly depends on the demand for those skills. Underlying these labour market theories is an implied gender neutrality, which for Africa is misleading. There is clear evidence that the perception of the economic role of women, rather than their actual role, influences the supply and demand variables in a skilled labour force. The gender composition of the labour force also influences supply and demand variables for goods and services, depending again on the perception of who is demanding what type of goods and services, and what types of goods and services are available.

The Malian agricultural sector is female dominated at the production level just as in most African countries. The majority of food crop and vegetable crop producers are women as they are charged with the tasks of fending for their families. Women work to produce food, as well as involve themselves in the marketing of vegetables, trading and farming. Farming here not only means horticulture such as, growing vegetables, but also includes raising of small animals such as sheep, goats and chickens. Female dominance is however limited to the production level end, as the number of women in leadership positions and decision making at level of the Ministry of Agriculture is limited.

This study aims at analysing the influence of gender and culture on leadership positions for women in the Malian Ministry of Agriculture. Specifically, the study shows:

- The demographic characteristics of women and men officials of the Ministry;

- The frequency of men and women in leadership positions at the Ministry; and

- The commitment of men and women at work. This study also:

- Evaluates the contributions of female leaders in the Ministry

- Identifies and discusses some of the obstacles and challenges faced by women; towards leadership positions in the Ministry; and

- Suggest ways to overcome the challenges.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Leadership and professional women

Professional women still face discrimination, and the "glass ceiling" phenomenon is still very much in existence in most parts of the world (World of Work: The Magazine of the I.L.O., 1998). Stereotypical attitudes towards women's ability to lead and succeed in business organizations exist as observed by several cross-cultural studies (Stead, 1985; Hunsaker & Hunsaker, 1986 and Gupta, Koshal, & Koshal, 1998). Likewise, a majority of male managers in China believe, "the managerial success of women is constrained by their lack of dedication to pursuing a career with minimal commitment to the employing organization, insufficient experience, little interest in managerial roles and the lack of proper education" (Leon & Ho, 1994). Studies also show that male managers perceive women as lacking leadership qualities or possessing inferior leadership traits. As a result many men feel uncomfortable working under female leaders (Sostella & Young, 1991; Leon & Ho, 1994; Lau & Kaun, 1998).

2.2 Gender and inequality

In the original auspices of Organisation Man, gender was not an important issue. However, in the contemporary view of corporate culture, it has become crucial to understanding gender and culture and the influence of devotion and commitment in the workplace. Gender inequality is not new, as both paid and unpaid forms of work consistently exhibit patterns of inequality. Analyses illustrate the way jobs are immutably assigned to one sex or the other (Rhyne & Sharon, 1993). However, the corporate culture debate asserted that only men were considered to be affected by changes in employment practices. Here only men were considered breadwinners, with women's role limited to supplement income (Leon1994)

When analysing women's interests and gender segregation, most scholars adopt Molyneux's (1985) approach which distinguishes practical from strategic gender interests: Strategic gender interests are at the base of women's subjection: the sexual division of labour, sexual violence, control of reproduction, and the domestic, to name only a few, constitute the boundary of womens' affairs. Practical gender interests, although defined by the concrete experiences women share, are strongly affected by class. Dealing with those interests will however not directly modify the basic causes of women's subordination (Barrig 1994). This approach has been used and interpreted in different ways, thus some scholars have criticized it and others have adopted it as an analytical tool. Those who criticize the practical/strategic gender interests approach argue that it becomes problematic to use in the case of women from the popular classes, as it is insufficient to explain their complex reality.

3. METHODOLOGY

The study was carried out in two stages. Stage one of the data collection was completed in January, 2006 and is based around a survey of the National Directorate of Agriculture and all the regional directorates where 690 upper middle and lower levels of management officers of the Ministry of Agriculture in Mali were included. This was a purposive sampling to ensure that all men and women were equally represented. Care was taken to sample all the projects directors and chiefs in all the regions of Mali so as to attain a comprehensive view the involvement of men and women in leadership positions.

Survey questions were arranged around several general themes within the respondent organisation, including demographic characteristics, promotional opportunities, commitment and contributions, organisational structures, and challenges and constraints. These questions were not weighted in order of importance, individuals were however instructed to choose in cases of multiple responses, those that best represented their situation. The Likert scale was used in the construction of some of the questions where respondents were given four options ranging from: Strongly agree (4), Agree (3), Disagree (2) and Strongly disagree (1).

The second stage of the research involved the qualitative interviewing of 40 men and women at the managerial levels and 30 at the lower levels from the initial survey. These individuals were 35 men and 35 women, who responded positively to the questionnaire request to take part in further qualitative interviews. The individuals were selected because they represented a similar sample (sector and levels of management) to the survey. The interviews were in-depth and semi-structured and were conducted outside the workplace to ensure confidentiality. On average these lasted an hour and were all tape-recorded. Questions focused around their experiences at work and its effects on their social and economic situation.

The data was analysed using simple frequency counts, percentages, means and histograms.

4. RESULTS

As compared to men within the Ministry of Agriculture in Mali, relatively fewer women (5) have a degree in agriculture. Also, much fewer women possess a diploma in agriculture (12) and certificate in Agriculture (17). These poor figures were due mainly to the socio-cultural setting in which women operate in Mali and the perceptions of women concerning agriculture.

In Mali, the culture and beliefs deprive the female child's right to education with preference given to the male child. Female children are denied education and are rather sent into early marriages. Traditional norms and values largely regulate a female child's life in Mali. One traditional norm is the strict division of labor based on gender. While a man typically generates income for the family outside the household, a woman is expected to take care of meal preparation, house cleaning, childcare and most other domestic chores in the extended family setting. Since these tasks do not directly generate income, a woman must depend on a man, whether it be her father, husband, or son, throughout her entire life for economic support (Cain 1982). Another traditional norm influencing a woman's life in Mali is the institution of purdah, an Islamic custom that limits the visibility and mobility of a woman outside the home. Purdah also ensures a strict observance of modesty and submissive behaviour (Kabeer 1988).

A woman's status as a wife or mother represents her only real option for social promotion and especially so since she is excluded from the public sphere (Mali, 1994). It is important that the family functions well because it is the principal unit within which an individual identifies and receives support (Davis and Blake 1956: Mannan 1989). After marriage, a woman usually goes to live in her husband's household. Here, she is evaluated on how properly she devotes herself to its function and the well being of its members. She is also expected to bear children, particularly sons because they are essential for maintaining the integrity of a household. Bairagi and Chowdhury 1994; Nosaka 2000 note that the fertility behaviour of young women is largely influenced by a strong cultural preference for sons. Compared to daughters, sons represent dependable economic assets and sources of future security because they will generate income for the household and remain with their parents to support them. Through sons, therefore, a woman not only gains social recognition, but also establishes a secure position in the household (Foner, 1984).

In this type of cultural environment, very few female children in Mali have the opportunity to attend school for longer times. There is also a general dislike for the agricultural profession by females in Mali. This is however an offshoot of the cultural roles assigned to the males and female children in the society. It is generally believed that the male child inherits land and should go into farming. The female child is confined to household work and child rearing. It is usually with this indoctrination coupled to the fact that they consider agriculture as a rather dirty job that most female students (even in higher institutions) consider agriculture as a domain for men.

The majority of men (73%) are within the 31 to 50 years age range with a mean age of about 49 years while most women (50%) are in the 31 to 40 years age range with a mean age of 36 years. Most men in the Ministry are older than the women because, it was only in the early 90s that women started opting for agriculture as a course and getting attracted into the Ministry. As such and until now, the Ministry is still male dominated (Figure 1).

4.1 Work Environment for Female Employees within the Ministry of Agriculture in Mali

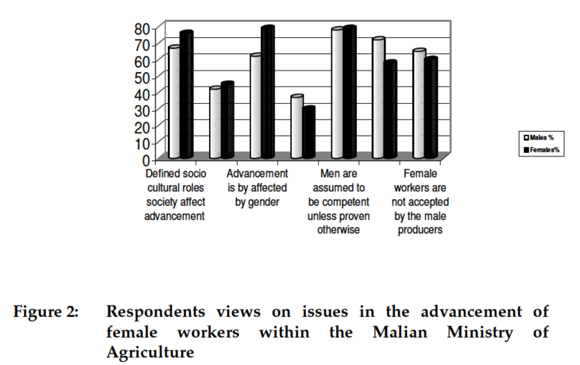

Respondents were asked six questions: (i) Whether advancement in the Ministry is affected by socio-cultural roles assigned to each sex by the society; (ii) Whether such advancement is based on merit or gender; (iii) The extent to which their organizations encourage female workers to advance up the corporate ladder; (iv) Whether men are assumed to be competent unless proven otherwise; (v) Whether females are perceived to be as committed to their jobs as males; and (vi) Whether female workers are accepted by the male producers (farmers) in the field.

In Figure 2, both the male and the female workers agreed that the socio-cultural context plays an important role in advancement issues. Also, a smaller proportion of male workers (42 %) than female workers (45.0 %) agreed that no-one feels disadvantaged. A smaller proportion of male workers (62% against 79% for females) agreed that the gender of the worker is a major factor in organizational advancement decisions and not the competence of the worker.

Similarly, when asked if the organization encourages females to assume leadership roles, 30% of female versus 37% of male workers agreed. It appears that an almost equal proportion of the female and male respondents (78% and 79%) in our survey perceive that men are assumed to be competent until they prove their incompetence in their organizations. However, a smaller proportion of female respondents (58 %) as compared to male respondents (72%) agreed that women are as committed to their jobs as men in their organizations. By examining the data in Figure 2, one can conclude that the percentage of male workers who agreed to the six questions was larger than the percentages of female workers who agreed.

The findings suggest that women feel disadvantaged in the Ministry and believe that organizations do not encourage them sufficiently to assume leadership roles and that a person's gender as well the socio-cultural roles assigned to each sex rather than competence is considered important in decisions related to who climbs the corporate ladder. Men are generally assumed to be competent both by men and women. Interestingly, women do not consider themselves as committed to their jobs as men think of women.

By far the most important management level for men was the middle management (372 or 66,9%), with junior management the most important for women (18 or 52,9%). This trend could be explained by the fact that the educational level of women is relatively lower than that of men within the Ministry, which inevitably has influenced their starting level. To be appointed as a Director in the Ministry, apart from other requirements, the candidate must have at least a first degree in Agriculture which only five (5) women currently have within the Ministry. According to the respondents, these five women are further constrained by their marriages to stay close to their husband and children. As such, they could not be posted to anywhere removed from their family. In the field, there is also the problem with women leaders not usually accepted by the rural producers.

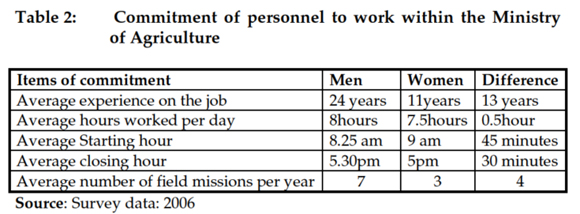

Table 2 shows that men within the Ministry have on average more years (24 years) of experience on the job than women (13 years). The unattractiveness of the Agricultural profession to women and the socio-cultural bias towards the education of the female child until the early 1980s have contributed to this trend.

There is not much difference between the number of work hours per day for men and women workers within the Ministry, however, there is a difference of 45 minutes in their starting time in the morning. This, the women explained was due to some family engagements as they have to take the children to school as well as prepare meals for the family before leaving home in the morning. For these reasons also, they would have to close early so as to rush to the market and prepare supper for the family.

Women within the Ministry could not engage in field missions as much as men because of their family ties, the harsh climatic situation in Mali and the poor accessibility to some areas which made some of these missions very difficult and unattractive for women.

The results presented above indicate that male workers, in general, do not perceive the special contributions women workers make at the workplace as women do. In a separate analysis not reported here, we found that the male workers do not perceive these contributions as being important. As a result, male workers are not appreciative or enthusiastic of the special traits women bring to the workplace, as reflected in Table 3.

Differences in opinion between males and females were observed in four areas namely: (i) Compassion/care in decision making, 77% of females agreed that they bring compassion and care in decision making while only 48% males saw this behaviour in female leaders (ii) Different perspective to organisational problems, 82% of females versus 50% of males agreed that female workers bring different perspectives to organisational problems; (iii) 76% of females versus 30% of males agreed that women are willing to "go an extra mile" and that they put forth additional efforts for the success of the organization; and (iv) 57% of females versus 30% of males agreed that women are more sensitive to human relations issues in the workplace. Almost an equal proportion of females and males agreed that females pay greater attention to details and focus on process rather than just results.

Both the male respondents and the female respondents agreed that socio-cultural elements such as beliefs within the Bambara culture that the place of the woman is the home and that women cannot lead where there are men, accentuated by Islamic injunctions about women, are issues that adversely affect the advancement of women in the Malian setting.

They also both agreed that the low qualification of most women within the Ministry hinders their advancement. While the men disagree that women have poor decision making capability, the women themselves said that they have poor decision making capability as well as lack initiatives to improve the workplace. However, men claimed that women lack leadership skills and cannot motivate workers, while women disagreed with these claims.

Lastly, women claimed that they do not put in extra hours to work because of other demands on their time such as family care and their social engagements coupled with the fact that the Ministry would not pay them for the extra hours.

The research findings suggest that men consider it quite appropriate for women to accept a slower rate of advancement in rank, change their job, or work harder than men in order to cope with discrimination within the administration. These approaches breed further discrimination. However, a large proportion (74%) of female workers believe, that gender bias does exist; however, they strongly believe they have to act collectively, participate as well as go for further training to improve their chances of advancement. Bennett (1998), in her study of women's struggles, argues that women may organize from practical or strategic gender interests depending on whether or not they link their problems to patriarchy and social class. Interestingly, Bennett allows for bridging these two types of gender interests by saying that "sometimes, women participate in protests or popular movements for practical gender interests, (and) their participation leads to an awareness of their strategic gender interests". Carver (1990) also aligns to this position, believing that being in contact with other active women may further develop women's gender consciousness.

The results of the study can be summarized as follows:

- By far the most important level of management for men was the middle management, with junior management the most important for women.

- Age within the sample was broadly distributed, but showed over-representation of ages above 40.

- Level of education was significantly different with the majority of the men respondents possessing first degrees and the majority of the women respondents holding only technical certificates.

- Female respondents within the organisation rated the leadership skills of women more positively when compared to their male counterparts.

- Female respondents perceived the Ministry of Agriculture in Mali is male-dominated and little is done for the advancement of women to help them fit into the organisational culture.

- Female respondents within the Ministry of Agriculture perceived that they make many positive contributions to the workplace, showing compassion and care in decision making, expressing willingness to go the extra mile, being sensitive in human relations issues, and offering fresh perspectives to organisational problems. However, men recognize these contributions to a significantly lesser extent.

- Female respondents claimed to be as committed to the organization as their male counterparts especially in terms of work hours. The male respondents denied this claim.

- Cultural elements such as beliefs within the Bambara culture that the place of the woman is the home and that a woman cannot lead where there are men, coupled with the Muslim religion, are issues that are negatively affecting the advancement of women in the Malian setting.

- Females' using legal means against accepting a slower rate of advancement to cope with gender-bias is not popular in Mali. Switching jobs, waiting and hoping that the situation will improve, accepting the situation as it is, and working harder than men are more acceptable approaches in dealing with the problem. A greater percentage of males than female workers believe in these approaches.

5. RECOMMENDATIONS

Although women are accepted to work in the Ministry of Agriculture in Mali, barriers exist for their advancement to upper management positions. To reduce these barriers, significant changes in the attitudes of male and female leaders along with organizational and cultural changes are needed. Instead of waiting for others to change, based on the findings of this study, a few recommendations can be made to women who wish to advance into upper management positions. Some steps that women can take to improve their chances of career success include:

- Women should urge that men and the workforce in general be informed about studies that demonstrate the value of women's managerial styles.

- Women should participate in organizational politics, aligning themselves with the individuals believed to be the next leaders in the Ministry. They should be prepared to challenge an inhospitable organisational culture.

- Men should be asked to attend workshops and training sessions that discuss how diversity in the workforce is conducive to greater creativity, better decisions, and ultimately greater productivity.

- Top management in the Ministry needs to understand the special traits that women bring to the workplace along with their special needs as employeesÂneeds which should ultimately be regarded as societies' needs (e.g. maternity leave).

- The Ministry can assist females in their advancement by playing a proactive role in creating a more female-friendly culture that includes visible senior management commitment to gender issues, aggressive recruitment of women at all levels of management positions, greater exposure to women of the upper management activities, mentoring, work-site childcare facilities, monitoring their job satisfaction, broadening their experience via job rotation and professional development via training.

6. LESSONS LEARNT

The study shows that both men and women have different traits and behaviour patterns and that these traits are helpful in creating an excellent work environment within the Ministry. It also shows that much needs to be done to sensitise society that women are also capable of handling leadership positions in Mali.

REFERENCES

BAIRAGI, R. & CHOWDHURY, M.K., 1994. Effects of parental gender preference on fertility In Matlab: Women, children and health, edited by V. Fauveau. Dhaka: The International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh. Bangladesh. Population Studies 48:21-45. [ Links ]

BARRIG, M., 1994. The difficult equilibrium between bread and roses: Women's organizations and democracy in Peru. In Jane Jaquette (ed.), The Women's Movement in Latin America. Participation and Democracy. Boulder: Westview Press. [ Links ]

BENNETT, V., 1998. Based protests in Mexico. In: Women's Participation in Mexican Political Life edited by Victoria Rodriguez [ Links ]

CARVER, T., 1996. Gender is not a synonym for women. gender and political theory: New contexts.bBoulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers. [ Links ]

CHOWDHURY, A., 1995. Families in Bangladesh. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 26:27-41. [ Links ]

CAIN, M., 1982. Perspectives on family and fertility in developing countries. Population Studies. [ Links ]

DAVIS, K. & BLAKE, J., 1956. Social structure and fertility: An analytic framework. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 4:211-235. [ Links ]

FONER, N. 1984. Ages in conflict: A cross-cultural perspective on inequality between old and young. New York: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

GUPTA, A.K., KOSHAL, M. & KOSHAL, R.K., 1998. Women in management - A Malaysian perspective. Women in Management Review, 13:1:11-18. [ Links ]

GUPTA, A.K., KOSHAL, M. & KOSHAL, R.K., 1998. Women managers in India. Equal Opportunities International, 17(8):14-25. [ Links ]

HUNSAKER, J. & HUNSAKER, P., 1986. Strategies and skills for managerial women. Southwestern Publishing; Cincinnati, OH. [ Links ]

KABEER, N., 1988. Subordination and struggle: Women in Bangladesh. New Left Review, 168:95-121. [ Links ]

LAU, S. & KUAN, H., 1998. The Ethos of the Hong Kong Chinese. The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong. [ Links ]

LEON, C.T. & HO, S.C., 1994. The third identification of modern Chinese women: Women Managers in Hong Kong. Chapter 3, Competitive Frontiers. [ Links ]

MDARN, 1994. Point d'Execution du Programme d'Activites de al Promotion Feminine a la date 20 Octobre,1994. Ministere du Developpement Rural et de l'Environnement, Direction Nationale de l'Agriculture,Coordination Nationale PNVA. [ Links ]

MANNAN, M.A., 1989. Family, society, economy and fertility in Bangladesh. The Bangladesh Development Studies, 17:67-99. [ Links ]

MOLYNEAUX, M., 1985 Mobilization without emancipation? Women's interests, state and revolution in Nicaragua" in Slater (ed.) New Social Movements and the State in Latin America. CEDLA Amsterdam: Latin American Studies, 29:233-60. [ Links ]

NEW YORK TIMES, 2003. Japan's neglected resource: Female workers, July 25, 2003. [ Links ]

NOSAKA, A., 1997. Mother-in-law's influence on daughter-in-law's reproductive behaviour in rural Bangladesh. Ph.D. dissertation, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA. [ Links ]

RHYNE, E. & HOLT, S., 1993. Women in finance and enterprise development. Draft contribution to World Bank Paper on gender and development. October [ Links ]

SO STELLA, L.M. & YOUNG, K., 1991. A study of women's abilities in managerial positions: Male and female perceptions. As quoted in Adler, N.A. and Israeli, D.N. (eds.), (1994). Women Managers in the Global Economy. Blackwell Publishers; Cambridge, MA. [ Links ]

STEAD BETTE, A., 1985. Women in management. Prentice Hall Publishers. World of Work: The Magazine of the I.L.O., (1998). Will the Glass Ceiling Ever Be Broken? Women still lonely at the top. February 24:2:6-7. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

SAFE/IPR/IFRA, University of Mali, Mali

Tel: 002236452372

E-mail: obonkus2@yahoo.co.uk