Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Agricultural Extension

versão On-line ISSN 2413-3221

versão impressa ISSN 0301-603X

S Afr. Jnl. Agric. Ext. vol.37 no.1 Pretoria Jan. 2008

Cultural variations regarding the nature and determinants of opinion leadership

G.H. Duvel

Professor/Director of the South African Institute for Agricultural Extension, Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences, Department of Agricultural Economics, Extension and Rural Development

ABSTRACT

This paper compares the findings from different countries regarding the nature and determinants of opinion leadership. The differences between white and black farmers in one country far exceed the differences between black cultures in different countries. White communities tend to have a bigger percentage of opinion leaders and socio-economic status is an important barrier to accessibility. Socio-psychological accessibility is a major constraint amongst white farmers, but not a factor whatsoever in black communities. In black communities, on the other hand, distance or physical accessibility is a serious constraint with the result that about 80 percent of the opinion leaders consulted live within a 2 km radius. This and the fact that most of the determinants normally associated with opinion leadership show a negative relationships (as opposed to the positive correlations in white communities), creates the suspicion that opinion leaders in black rural communities are neighbours or, more likely, members of the extended family.

Keywords: Opinion leaders, cultural influence, diffusion and determinants of opinion leadership.

1. INTRODUCTION

Focusing communication messages on certain "influentials", in the assumption that their influence will come to bear in the further diffusion to and influence on the other members of the target audience, makes sense, especially if personal influence is called for but large numbers or a wide change agent/client ratio make it difficult. This is typically the case in many developing countries where there is usually a shortage of extension workers to facilitate a quick dissemination of agricultural messages. In this context it is fair to assume that the use of influential farmers or opinion leaders can significantly contribute towards an increased diffusion effect.

However, there is, according to Chege et al (1976) also evidence suggesting that the "trickle-down" of information and influence does not always occur to a significant degree. Lipton and Longhurst (1985) and Parent and Lovejoy (1987) also come to the conclusion that the influence of opinion leaders is grossly over-estimated.

This could be attributed to the wrong identification of opinion leaders, but at least suggests that their influence is not really known and that little is known about the factors contributing to their influence and whether and to what degree these factors vary significantly between different communities or cultures. This paper draws from a few studies conducted in different countries, namely Uganda (Adupa & Düvel, 1999), Lesotho (Williams, 2005), and South Africa (Duvel, 2005), in trying to find some answers to the above.

2. METHODOLOGICAL ASPECTS

The research approach used in the different surveys and on which this publication is based, varied but had certain commonalities. In all cases use was made of semi-structured interview schedules and the identification of opinion leaders done by the socio-metric method. In response to questions aimed at identifying opinion leadership, respondents had to name the individuals that they would consult if they wanted information or advice on a specific topic as well as those actually consulted and those they regarded as knowledgeable. In most projects preference was given to smaller populations rather than samples of bigger populations, but invariably the nominated individuals outside the group of respondents were also incorporated in the analyses as far as certain data was concerned.

3. RESULTS

3.1 The scope of opinion leadership

Earlier research among white commercial farmers in South Africa (Pienaar, 1983) left the impression of a relative small number of opinion leaders having an influence on a large number of followers. This was later found to be very unlikely (Düvel, 1996) and attributable to an incorrect identification of opinion leaders. In response to a question who respondents would consult if they were seeking information or advice on a specific issue, there was a very clear reluctance, perhaps for reasons of prestige or image projection, to nominate individuals as opinion leaders that were not generally regarded to be very knowledgeable. The fact that this led to an incorrect identification of opinion leaders became evident when respondents were requested to distinguish between individuals known as knowledgeable and those really consulted.

This phenomenon, however, does not occur among black small-scale farmers in the sense that they are more candid and open when reporting about their consultation behaviour and they make little or no difference between individuals that they would consult and those that really are consulted. In these communities there is little danger of the wrong individuals being identified.

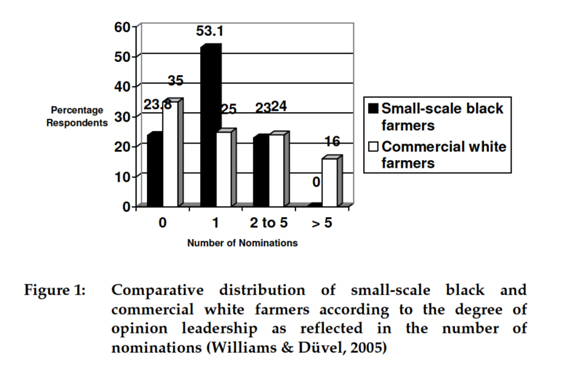

As far as the number or percentages of opinion leaders in a farming community are concerned, the findings of Williams & Düvel (2005) from Swaziland appear to be pretty representative of the black farming communities.

Accepting nominations of two or more to qualify as opinion leaders, about 23 percent of the farming population can be termed opinion leaders (Figure 1). In white commercial farming communities this percentage is usually higher, varying from about 30 percent (Van der Wateren, 1986) to as high as 40 percent (Bembridge & Burger, 1976), and there are also clear indications of these opinion leaders to be more monomorphic as opposed to the more polymorphic opinion leaders in black farming communities.

3.2 Determinants of opinion leadership

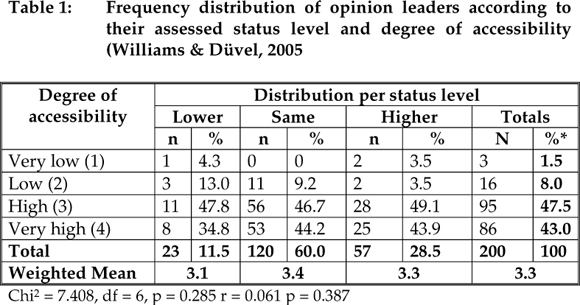

Socio-economic status is generally accepted as being an important factor in influencing opinion leadership or the pattern of consultations, in the sense that followers usually seek advice from opinion leaders with a higher socio-economic status (Rogers 1983), but if the difference in status is too big the decreasing accessibility can be expected to prevent the flow of information. This appears to be the case among the white farmers (Düvel and Van der Wateren, 1988; van der Wateren 1986) but it does not seem to apply to the black farmers. When black farmers were asked to assess the accessibility of opinion leaders they previously had categorized as having a lower, the same, or a higher socio-economic status than themselves, there was no significant difference regarding accessibility (Table 1).

Even the generalization made by Rogers (1983), namely that opinion leaders have a higher socio-economic status than the followers, does not seem to apply in many black cultures.

Other factors investigated that have opposite influences or relationships in the black and white cultures are age, education, production efficiency and farm size. The normal expectancy would be that opinion leaders do not necessarily differ from their followers in age, but that they are better educated (higher qualifications), have more contact with extension, have bigger farms and are more productive or efficient farmers. In the culture of the small scale black farmers almost the exact opposite appears to be the case. The findings from Lesotho (Williams and Düvel, 2005) indicate that in black farming communities the opinion leaders, particularly the strong opinion leaders, tend to be older, but have lower levels of education (r = -0.257; p = 0.01) and are, based on production efficiency, not better farmers at all. The opposite rather seems to be the case.

The absence of a significant correlation between farming efficiency and opinion leadership and the fact that only 34.5 percent of the respondents seek advice from individuals that they regard to be more efficient than themselves, seems to indicate that farming efficiency or competence is not such an important issue in a farming environment that is primarily subsistent in nature.

In Lesotho the strength of opinion leadership is negatively related to contact with extension, which could be an indication that extensionists are not aware of or not using the prominent opinion leaders yet and/or that there is a negative relationship between opinion leadership and perceived credibility of the extension service.

3.3 Accessibility of opinion leaders

Accessibility is probably, next to competence, the most important dimension of opinion leadership. To function as an opinion leader, an individual must not only be seen to have superior or a higher level of knowledge, but there must also be the willingness on the side of potential followers to seek his/her advice, and for that he/she needs to be perceived as accessible. This accessibility has a physical and a socio-psychological dimension:

(1) Physical accessibility.

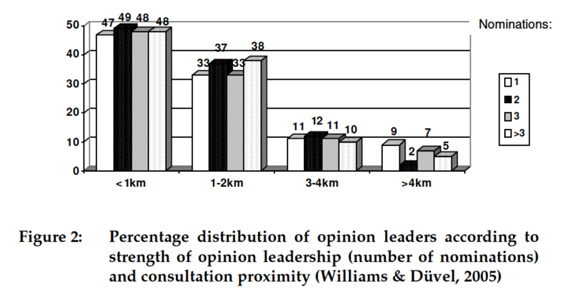

If individuals form network links that require the least effort (Rogers and Kincaid, 1981), people in the immediate environment are likely to have more influence than those who are far, because they are physically more accessible when their advice is needed. In the case of the white commercial farmers, the distance or consultation proximity (distance between follower and opinion leader) does not seem to influence the consultations within the bigger community. However, in the small and resource-poor farming situations (Figure 2), the physical distance can be a serious limiting factor as is shown by the following findings from Swaziland (Williams & Düvel, 2005).

About 50 percent of the opinion leaders consulted, live within 1 km radius and almost 80 percent within a distance of 2 km. This could give the impression that opinion leaders are mostly neighbours or members of the own extended family.

(2) Socio-psychological accessibility

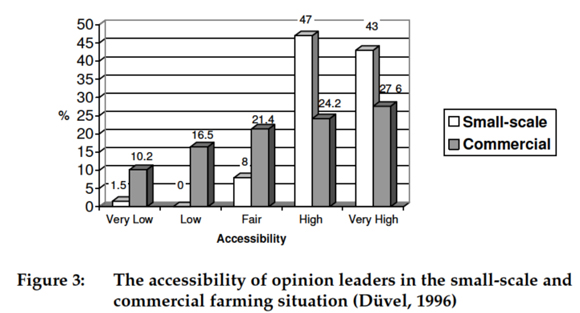

All surveys done among black farmers, whether in Uganda, South Africa, Lesotho or Botswana, indicated that socio-psychological accessibility is not a constraint. This is in contrast to the situation among white commercial farmers as can be seen from Figure 3.

About 90 percent of all black opinion leaders were assessed to have a high or very high accessibility compared to only about 50 percent in the case of white commercial farmers. This means that accessibility is much more critical in the culture of white commercial farmers and largely determines the consultation pattern. Unlike the black farmers, where there was hardly a difference in accessibility assessment between those farmers classified as very knowledgeable and those actually consulted, there were very significant differences in the case of the white commercial farmers. The farmers classified as knowledge leaders, were assessed significantly lower in accessibility, which largely explains why they were not consulted or why their identification and involvement did not have a significant influence on the total extension impact.

Further evidence of the unequal importance of accessibility is found in the relationships between opinion leadership and certain determinants of opinion leadership or factors associated with it.

3.4 Accessibility related factors

Where accessibility has been found to be a limiting factor this has led to further investigations to better understand the concept and factors related to it. These factors include (a) friendship versus kinship, (b) fear of exposure and (c) reciprocity of influence

The assumption, that accessibility is particularly high among friends, led to an analysis of the relationship between accessibility and friendship. This relationship is highly significant among white commercial farmers (r = 0.54; p = 0.0001), but absent in the black small-scale farming sector. If anything it is the acquaintances that have the edge regarding accessibility. This leads to the strong suspicion that opinion leaders have their main influence within the extended family. For this reason seniority rather than competence is related to opinion leadership in black communities.

One of the major factors responsible for accessibility or the lack thereof is fear of exposure.

The reluctance to consult somebody can in many cases be attributable to the fact that consultation implies recognition of not knowing and thus exposing oneself. This barrier can be overcome if there is reciprocal consultation, i.e. if two individuals consult and advise each other in different fields. Both these aspects were found to correlate significantly in the white commercial situation but not in the black culture, emphasizing once again that accessibility is not a problem or even an issue in many black cultures

4. CONCLUSIONS

1. The fact that strategies based on opinion leadership don't always meet expectations must be ascribed to their wrong identification in some cultures.

2. Accessibility is a critical dimension in some cultures, whilst it is not a factor in others. However, more research is required to understand this concept and the degree to which it is a constraint in different cultures.

3. Opinion leadership strategies should be combined with other local communication network phenomena.

4. An understanding of the diffusion process and its promotion may be better served by a focus on negative opinion leaders, an area largely overlooked by research.

REFERENCES

ADUPA, J., & DUVEL, 1999. The importance of opinion leaders in agricultural production among male and female farmers of the Kusenge Parish in the Mukono District of Uganda. S. Afr. J. Agric. Ext., 28:32-44. [ Links ]

BEMBRIDGE, T.J. & BURGER, P.J., 1976. The importance of opinion leaders in extension. S. Afr. J. Agric. Ext. 5:13-17. [ Links ]

CHEGE, F.W., RÓLING, N., SUURS, F. & ASCROFT, J., 1976. Small farmers on the move: Results of a panel study in rural Kenya. Paper presented at the Fourth World Congress of Rural Sociology, Toran, Poland, August 9-15, 1976. [ Links ]

DÜVEL, G.H., 1996. The role of competence in the identification and functioning of opinion leaders. S. Afr. J. Agric. Ext. 25:18-26. [ Links ]

DÜVEL, G.H. & VAN DER WATEREN, J.J., 1988. The identification and accessibility of opion leaders. S.A. Institute for Agricultural Extension. Research Report. (unpublished). [ Links ]

LIPTON, M. & LONGHURST, R., 1985. Modern varieties: International research and the poor. Washington: World Bank Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research. Study Paper 2. [ Links ]

PARENT, F.D. & LOVEJOY, S.B., 1987. Communication strategy: Does the two-step still work? ACE Quarterly, 1:5-7. [ Links ]

PIENAAR, J., 1983. Experience with permanent audiences as extension method in the Stellenbosch viticultural area. S. Afr. J. Agric. Ext. 12:53-60. [ Links ]

ROGERS, E.M., 1983. Diffusion of innovations. 3rd Ed. New York: The Free Press. [ Links ]

ROGERS, E.M & KINCAID D.L., 1981. Communication Networks: Toward a new paradigm for research. The Free Press, New York. [ Links ]

VAN DER WATEREN, J.J., 1986. Opinie-leierskap in landbou-ontwikkeling. PhD thesis, University of Pretoria, Pretoria (Unpublished). [ Links ]

WILLIAMS, R.F. & DUVEL, G.H., 2005. Nature and determinants of opinion leadership in Lesotho. S. Afr. J. Agric. Ext. 34(2):260-274. [ Links ]

WILLIAMS, R.F. & DUVEL, G.H., 2006. Factors contributing to the accessibility of opinion leaders in Lesotho. S. Afr. J. Agric. Ext.35(2):120-131. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Prof G.H. Duvel

Department of Agricultural Economics, Extension and Rural Development

University of Pretoria, Pretoria 0002

Tel. 012-4203811, Fax. 012-420-3247

E-mail: gustav.duvel@up.ac.za