Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

HTS Theological Studies

versión On-line ISSN 2072-8050

versión impresa ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.79 no.3 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v79i3.8170

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Zimbabwean women's experiences at Johanne Masowe WeChishanu Apostolic churches' open ground gatherings

Priccilar VengesaiI; Linda NaickerII

IHerbert Chitepo Law School, Great Zimbabwe University, Masvingo, Zimbabwe

IIResearch Institute for Theology and Religion, Faculty of Human Sciences, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The Constitution of Zimbabwe guarantees religious freedoms and freedom of association including for religious purposes. While people can gather for religious purposes, the main thrust of this article is to investigate and unpack environmental crises caused by Christian gatherings and how women are affected by these environmental crises. The article focuses on the Johanne Masowe WeChishanu Apostolic churches. Environmental rights in terms of the Constitution recognise the need for one to be in a healthy environment. It also imposes an obligation for the non-occurrence of land pollution, land degradation, or destruction of the ecology and the advancement of conservation and ecological sustenance. Through observation, it was established that the Johanne Masowe WeChishanu Apostolic churches hold their church services in an open ground with no ablution facilities and no availability of critical basic resources such as water and medical facilities. The article contends that the environmental crisis caused by open gatherings affects women and men differently. Equally, the effects of climate change leave women in an unhealthy environment during church gatherings. It is further argued that such consistent gatherings in one place cause environmental degradation and deforestation. Leaning on the feminist social justice theory, this article advocates consideration of approximately prepared meeting places for the Johanne Masowe WeChishanu Apostolic churches gatherings inclusive of provision of basic ablution and clean water facilities.

CONTRIBUTION: This article makes a significant contribution to the study of gender in the context of environmental challenges and recommends greater involvement of women in the fight against environmental crises.

Keywords: degradation; gatherings; environmental crisis; religious setting; women's rights; deforestation; pollution; social justice.

Introduction

Emerging feminist scholarships are unveiling the interrelatedness of gender, economic development and environmental changes (Resurreccion 2017). Research from the 1980s reveals that women are key participants in environmental stewardship and economic development. Perceptions of the link between gender and environment vary. Some perceptions consider women to have a special and inherent connection with the earth while others see the link between women and the environment as that of being resource users and eco-political agents (Resurreccion 2017). Women are considered as being the ones who express slightly greater environmental concerns than men (Xiao & McCright 2017).

In this article, we provide an overview of the discourses around gender and the environment in religious settings. We foreground the gendered nature of environmental injustices that prevail during religious open-space gatherings. Gendered environmental injustice occurs when men and women are affected differently by environmental challenges (Sze 2017; Walker 2017). The main goal of this research is to investigate the challenges experienced by women in the Johanne Masowe WeChishanu Apostolic churches during their church services and how this perpetuates the already existing gender injustices and inequalities that prevail. We argue that in this era of climate change, women's environmental rights and the environment itself are at risk during the Apostolic Johanne Masowe WeChishanu churches 'open space gatherings'.

In the following section, we present the methodology and the theoretical framework. This is followed by a literature review on the interconnections of gender and the environment. Data analysis is presented, and the findings and the discussion of those findings form part of the penultimate section, followed by the conclusion and recommendations.

Methodology

This article assumes a qualitative research approach. We employed the qualitative approach because it is the most prudent method for ascertaining the different experiences of women and men as it relates to their specific contexts. For this research, we conducted a case study. A questionnaire was prepared in line with the research objectives with semi-structured open-ended questions that identify the important variables. McMahon (2020) describes a case study as an illustrative approach normally used to illustrate the challenges or difficulties of a community. Thomas (2011) proffers that a case study helps to develop in-depth understandings of a given community, department, or group of people. A case study also goes beyond explaining or understanding occurrences in detail as it brings about practical solutions to the specific challenges within the community or organisation under study. This makes the study more practical. Gibson et al. (2009) identify a population as the totality of a group of people or objects the researcher intends to involve in a study. The population of the proposed study comprised 50 women and 50 men between the age of 30-50. In both samples, half of each were members of the church and the other half were non-members. A deliberate effort was made to include the above-mentioned age groups for consideration of experiences and maturity. The sample size for the current study comprises 100 participants.

Theoretical framework

This article applies feminist social justice theory. The feminist social justice approach is grounded in the real struggles and issues of women and recognises the link between theories and practices (McLaren 2019). These practices can be situated in religion, culture, or any walk of life. Recognising the link between theory, analysis and real-life struggles allows for an analysis that is informed by, and may inform, struggles for social justice on the ground. Jaggar (2009) argues that non-ideal theories of justice are better suited to effectively counter injustice by beginning from actual social and political conditions.

Gender and the environment

While to be male or female is biologically determined, gender is a socially constructed phenomenon. In the patriarchal construction of gender, specific roles are accorded to males and females. Men are constructed as leaders and heads of households while women are constructed as docile, meek and subservient (Van Marle & Bonthuys 2007). Van Marle and Bonthuys (2007:22) posit that while sex is about biological roles and features of women, gender constructs are societal roles.

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) (2007) defines environment as: 'the sum total of all surroundings of a living organism, including natural forces, human-made, and other living things'. De Young (1999) views the environment not to be limited to its verbal meaning of nature and human environment but also to include environmental psychology that focuses on the behaviour of humans in any given environment.

Discussions on gender and environment have been centred on the analysis and critical examination of gender relations in different environmental contexts (Arora-Janson 2017). It is now common knowledge that environmental challenges are gendered. While men and women are both agents and victims of environmental constraints, they are ultimately affected differently with women bearing the brunt of environmental crises (Morrow 2017). Women are affected the most because their social responsibilities which include, among other things, fetching water, accessing and preparing food and obtaining fuel are closely linked to the environment. These gendered tasks put excessive strain on women. Moreover, dependent women often have limited or no agency because men hold the economic upper hand. Women are often excluded from decision-making processes for policy change and implementation. It is also argued that people in rural areas, in developing counties where there is high dependence on local natural resources, are the most vulnerable (FAO 2011).

As posited by Neumayer and Plümber (2007), the interconnection between poverty and vulnerability to climate change is flagrantly apparent. In Zimbabwe, there is a disproportionately higher percentage of poor women than poor men (Malaba 2006), making poor women disproportionately more vulnerable to the impact of climate change than poor men (Neumayer & Plümper 2007). Given the increased environmental instability, women will face particular challenges given their primary caregiving roles in times of disaster and environmental stress. Despite these challenges, many women have developed adaptive strategies to protect the sustainability of their environments and livelihoods. For example, poor nomadic women may have a relatively high adaptive capacity because of their intimate knowledge of their natural environment (Pearl-Martinez 2014). Their vast wisdom through experience is useful in mitigating climate change, tackling the effects of disasters, and developing skills that best deal with the situation at hand. Credit can also be given to women's role-play as caretakers at household and community levels. Significantly, the gendered construction of such roles places women in a better position to contribute skills to tackle situations that are caused by the changing climate.

Although women and men can adopt and develop skills, scarcity of resources is often devastating. Hence the sustainability of the whole social, economic and political sphere is weakened (Pearl-Martinez 2014). FAO (2017) Domestic work pressure, a lack of access to productive assets, exclusion from significant opportunities, as well as access to agricultural aid, hamper efforts to ensure sustainability in the use of land. Stromquist (2001) posits that issues such as gender inequality pose a threat as they aggravate or disturb food security in many countries. Stromquist (2001) postulates that weather variations that are climate induced together with the act of destroying vegetation force women and younger girls to spend more of their time walking miles to get access to food and water. These activities often rob them of the time to invest in life-changing, income-generating projects. Limiting circumstances, therefore, do more harm than already done as it reduces or weakens the physical and mental strength women possess. The girl child, in particular, is severely affected as access to education becomes compromised.

Argawal (2009) argues that besides discovering women's and men's ability to manage environmental changes, gender also unearths faint structural injustices that have a devastating effect on women. Socially constructed roles, specifically gender-based division of labour, dictate how people interact with their surrounding environment. Neumayer and Plümper (2007) argue that these established relations towards natural resources, in turn, determine how different environmental risks and threats such as resource degradation, climate change or disasters affect women and men. These differentiations inevitably mean a discrepancy in perceived priorities, as well as the acuteness of rampant environmental challenges.

Gender and the environment are also linked to sustainable development. It can be argued that due consideration must be given to the prevailing gender situation within a society for the enhancement of the sustainability of said society's relationships with nature (Littig 2017). The importance of gender in environmental governance for sustainable development came to the fore in a series of United Nations summits (Death 2011). These summits changed the discourse of sustainable development and linked it to gender and the environment (Foster 2011). Thus, the understanding of environmental problems and policy solutions must be done in the context of gender disparity (Foster 2011, 2014). Furthermore, the involvement of women in environmental policy-making processes has the potential to bring ideas, approaches, and strategies that can assist in ameliorating environmental challenges. It thus remains necessary to involve women in the discourse of environmental sustainability (United National Environment Programme [UNEP] 2016).

Significant to this study is the link between gender and the environment and religion. From religious doctrines, to faith, and the way in which they hold their meetings and special gatherings, religion clearly impacts and is impacted by the gendered nature of environmental crises. In the next section, we elucidate through data analysis the extent to which gender and the environment are linked to religion with a particular focus on the Johanne Masowe WeChishanu Apostolic churches' gatherings.

Research participants

In this section, we present an analysis of the reviews and data collected as well as an interpretation of the findings. The data is synthesised into simple graphs and charts for ease of comparison and viewing. Tables, graphs, and pie charts are used to display the results. A total of 100 participants were targeted. Eighty questionnaires were returned which shows a response rate of 80%. This shows that the research was highly successful and balanced. A response rate of more than 75% is a great response (Parker 2017). The high response rate can be attributed to the high literacy of the people. The sample was from a group of people with an interest in the subject matter; hence, they were willing to participate. Among the respondents, 55% were females and 45% were males. Of the 80 respondents to the questionnaires, 46 were people between 35 and 40 years. They are well-versed in development issues to have an interest in the subject matter. Sixteen participants representing 20% of the sample were in the range of 41 and 45, followed by 18 participants aged between 45 and 50 constituting 22.5%.

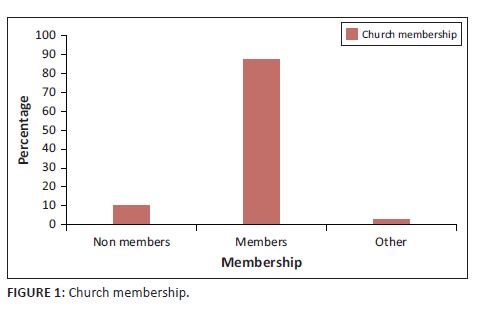

Figure 1 shows that most of the participants were members of the Johanne Masowe WeChishanu Apostolic churches. Eighty-seven per cent were members while 11% were non-members of the church. Two per cent of participants indicated other. These could be those who have constantly visited the church but remain unsure if they are yet members of the church. These results show that the sample was successfully purposive. The members of the church were asked to indicate the duration of their membership. All indicated that they were members of the church their whole lives; hence, they were born into membership. These results reflect how the members hold dear their religion and it also shows how women, in particular, have a strong attachment to the church.

Meeting frequencies

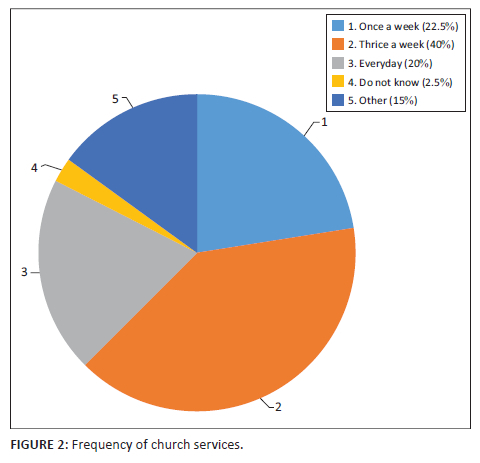

Figure 2 represents the number of church services conducted per week. A total of 22.5% of participants mentioned that the services are held once a week while a larger number of 40% noted there were three services each week. About 20% thought the church services were every day because they see people under the trees every day. These participants also highlighted the kind of services they thought took place on a daily basis. At least 17.5% of the participants' answers ranged from 'I don't know', and 'other'. Despite the discrepancies, the results show that the gatherings are very frequent which means more damage to the environment in a short space of time.

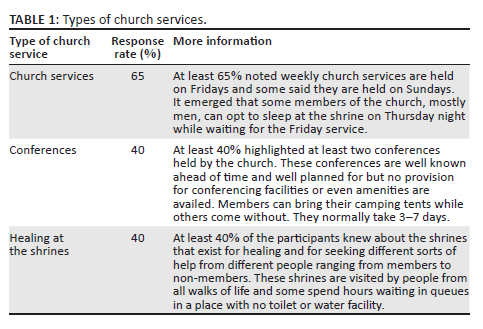

Types of church services

Table 1 shows that there were participants who understood the working of the church as most of them identified almost the same services and highlighted what is done. Most members identified more than one service. The findings show that the gatherings take place throughout the week. Even though the gatherings differ in size and the reason for such gatherings varies, participants indicate that they spend much of their time at the meeting places. Air pollution, land pollution, and water pollution are prevalent as some of these gathering places are typically close to rivers. This is the case of Mucheke, a high-density residential area in Masvingo town, Zimbabwe.

Types of places used by the church for their services

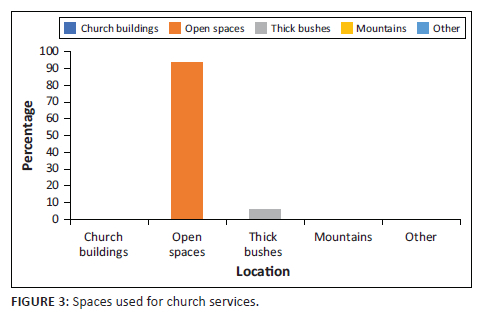

The majority of participants, 93.75%, mentioned that the church uses open spaces, while the remaining 6.25% mentioned that the church uses thick bushes as their places of worship. No participants identified buildings or mountains as the church's place of worship. This information is graphically represented in Figure 3.

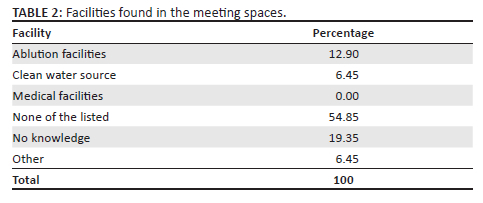

Facilities found in the meeting places

Table 2 shows the facilities identified as available in the open spaces used by the church. A total of 54.85% of the participants mentioned none of the facilities listed (ablution, medical, and water) existed in the spaces, while 19.35% of the participants stated that they had no knowledge of the existence of any facilities. A total of 12.9% of the participants responded that there were ablution facilities provided and about 6.45% indicated that there were safe water sources provided for those who had submitted their applications to the city authorities and were allocated the land. Some churches are digging pit latrines and rubbish pits in the vicinity. The findings do indicate that there are governmental regulations in place and some churches are now responding. The response rate is, however, very slow as many do not as yet have any facilities.

Women need to wash more frequently if they are in their menstrual cycles. They need to frequently change baby diapers or nappies. They need a safe space to dispose of either the diapers or the sanitary pads lest they will be dumped either too far or too close to the place of worship. All this affects and adds to the environmental crises that we are experiencing currently.

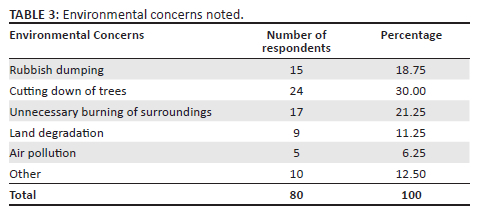

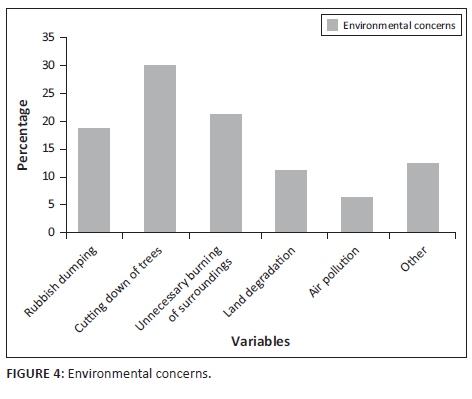

Environmental concerns noted in the spaces

The question required participants to rate environmental challenges caused by the Johanne Masowe WeChishanu Apostolic churches in their open ground gatherings. The responses weighted the concerns from the highest concern to the lowest concern according to the participants. Most participants felt cutting down of trees was major among the others. Unnecessary burning of surroundings was rated second while rubbish dumping received third rating and land degradation was rated fourth by participants. These four may be viewed as the main environmental challenges caused by the Johanne Masowe WeChishanu Apostolic churches.

The questionnaire allowed the participants to provide any other information that may be relevant to the study. It emerged that the main problems that the church faces are the effects of frequent rains which disrupt their worship services. It also emerged that because the church does not have enough money to purchase land, they are consistently confronted by governmental authorities when they find a place of worship. The council or local authorities claim that the places they occupy are not zoned for worship. Moreover, participants indicated that recently the church has been experiencing splits. Resultantly, within the same area, around five or more different groups can be seen holding church services. This exacerbates land degradation and deforestation.

Findings, analysis and discussion

Data analysis reveals that human beings impact the environment in different ways as indicated in Table 3 and Figure 4. Most of the environmental challenges that are apparent from the religious gathering arrangements of the Johanne Masowe WeChishanu Apostolic churches cause land pollution, deforestation, air pollution and land degradation. These environmental challenges in the current context of prevailing climate change, raise great concern and reveal that women suffer the effects of the environmental crisis to a greater degree than men. For instance, the burden of travelling long distances to fetch clean and safe water rests on women's shoulders. Accessing firewood or choosing an alternative energy source is also the prerogative of women. Caring for the sick or injured in the midst of crippling environmental and economic challenges rests on women to a far greater extent than it rests on men. Smith and Leiserowitz (2013) define environmental challenge as the existence of crises in the environment in such a way that it can cause harm to (wo)men or the environment. Machingura (2011) notes that religious gatherings such as those conducted by the apostolic sect who are the champions of open-air gatherings have various impacts on people's lives and affect the environment. This study finds that some environmental problems plaguing Zimbabwe are perpetuated through religious open-ground gatherings. These include desertification, deforestation, and air and water pollution. Kiarie (2020) and Bodjongo (2020) submits that a number of open-ground church gatherings are taking place in residential areas causing environmental pollution and noise pollution to the residents of those particular communities.

Deforestation

The term deforestation refers to the removal of forests and trees (Van Kooten & Bulte 2000). Its effects on the loss of biodiversity and increasing the greenhouse effect are rampant in developing countries (Barraclough & Ghimire 2000). With agriculture and urbanisation being the leading causes of deforestation, religious open-space gatherings play a role in the escalating crisis. This is corroborated by the findings of this study that such spaces are rapidly increasing in Zimbabwe, where shrines are now found in almost every available open space. The land is cleared to create these places for religious purposes.

There are surmounting environmental challenges that emanate from deforestation, which include desertification (Gupta et al. 2005), climate change (Chomitz et al. 2007), low rainfall in the lower regions (Lawton et al. 2001), drought (Bruijnzeel et al. 2005) and increased dry seasons (Chomitz et al. 2007). According to Taylor and Kaplan (eds. 2003), by destroying vegetation, humans are put at great risk. In Zimbabwe, environmental degradation is at the top of current environmental challenges caused by religious open-ground gatherings. While people have the right to worship, that right should not infringe on the rights of others to live in a safe environment. When worship is unregulated, it ceases to be a blessing and becomes a nuisance and in some instances, a threat (Ozdemir 2008).

Unarguably, women's increased vulnerability is caused by a number of factors such as poverty, weak governance and unjust laws. However, Sibanda (2012) posits that the key reason that leaves women more vulnerable to environmental challenges than men is their lack of agency to speak for their environmental rights. One of the problems suffered by women as a result of deforestation is the increased competition for products they access from the forest such as indigenous fruits, medicine and firewood. Sahney, Benton and Falcon-Lang (2010) align this kind of environmental tragedy to social problems that women encounter because of their socially constructed gender roles. This study reveals that in the context of environmental crises, women suffer the most compared to men.

Air pollution

Another environmental challenge that this study identified in relation to religious open-ground gatherings is ambient air pollution. Religious open-ground gatherings contribute to air pollution through their contribution to dust storms. Dust storms affect the air quality available for human breathing and this may affect human health. Tabari et al. (2020), for example, expose the link between COVID-19 and air pollution and posit that airborne particles assist in spreading the virus.

As part of the ritual of religious open-space gatherings, a fire is made at night vigils. These fires, according to Gozalo and Morillas (2017), release toxic substances and when inhaled by human beings can affect their health. People attending these religious open-space gatherings and surrounding communities, both children and pregnant women, are exposed to air pollution. Air pollution has disastrous effects on human beings as it increases their chances of having asthma. In pregnant women, air pollution can affect foetus brain growth (Tabari et al. 2020).

Land and water pollution

Religious open-ground gatherings also contribute to land and water pollution. Land and water pollution have been identified as primary causes of many health problems confronting human societies (Gupta et al. 2005). Waste dumping from religious open-space gatherings results in the accumulation of solid and liquid waste materials that contaminate soil and groundwater.

Dumping of litter on such sites also causes pollution by releasing chemicals and micro-particles as it degrades. The depositing of waste onto an area of land affects the permeability of the soil formations below the waste and this can either increase or reduce the risk of land pollution. Van Kooten and Bulte (2000) argue that the higher the permeability of the soil, the higher the chances of land pollution. Local authorities like the Bulawayo City Council have accused the worshippers of fouling the environment as they do not have approved ablution facilities (Mujinga 2018). In an interview with Newsday (2022), the Bulawayo City Mayor shared that:

Open-air churches, mostly the open ground Apostolic Faith sects, do not have toilets or running water, exposing the congregants to diseases. Moreover, these churches are a source of discomfort to residents as they make noise through loud singing also … Newsday (2022:1).

He went on to say that diseases like typhoid and dysentery thrive in places where there is no clean water and where hygiene is poor; this puts further strain on the environment.

Pollution, whether in water, land or air, is regarded by Karimakwenda (2010) to have adverse effects on human lives with women facing increased risk because of various societal structural inequalities and biological factors. These factors include informal jobs that most under-resourced women occupy, traditional and cultural roles, motherhood, and menstruation.

Women's gendered roles dictate that they perform household tasks that render them vulnerable to pollution through interaction with polluted water sources. Such duties performed by women even during open-ground gatherings render them susceptible to diseases. Furthermore, women occupy low-paying jobs such as cooks and cleaners (Mumoki 2006). This research revealed that most of the Johanne Masowe WeChishanu Apostolic Churches women trade informally, increasing their vulnerability to food insecurity and other distresses during times of drought because of increased pollution. Moreover, low harvests and droughts often cause increases in food prices. This impacts women-led households more than other demographics.

The contamination of nearby water sources leads women and girls to walk long distances in search of clean water. According to Shandra and London (2008), this puts a physical burden on women robbing them of valuable time that they could utilise for developing skills, engaging in projects and furthering their studies.

Land degradation

The dangers of open-ground gatherings are numerous but the most important one is the health hazard to the environment and community because of pollution and open defecation (Gozalo & Morillas 2017). Land degradation affects large parts of Zimbabwe both in communal and urban areas where annual soil loss averages 3.3 tons per hectare. In commercial areas, soil loss averages 0.6 tons per hectare per year (Zimbabwe Newspapers 2013). The most obvious impact of land degradation is the degradation of thousands of hectares of the country's rangelands where a lot of religious open-space gatherings take place. Environmental problems resulting in land degradation caused by open-space gatherings add more misery to the environment. According to Bhatia and Sharma (2010), the poor and the vulnerable are hardest hit by environmental deterioration in any society. In most contexts, including Zimbabwe, women suffer the brunt of land degradation the most. This is also evidenced through the study of the environmental crisis promulgated by the Apostolic Johanne Masowe WeChishanu churches.

Conclusion

This article brings to light the impact the open-ground gatherings of the Johanne Masowe WeChishanu Apostolic churches have on the environment. Despite its noble reason to worship God and to help people on a spiritual level, the environmental challenges it presents cannot be ignored. Deforestation, air pollution, land and water pollution, and land degradation are crucial issues affecting the environment and the well-being of people and the ecosystem. In light of this, more deliberate and concerted efforts must be made to improve the conditions of worship at these gatherings, not only for the sake of worshippers, but for the sake of the environment. The deep impact these gatherings have on the lives and health of the women attending is stark. The study findings revealed the harsh realities women must endure and call for all stakeholders inclusive of religious organisations, government, congregants and local communities to engage collectively in order to stem the tide of the environmental crisis perpetuated through religious gatherings in Zimbabwe. The study, therefore, recommends that:

-

Ablution facilities be provided or constructed where the church meets for church services and conferences.

-

Compliance with environmental regulations on cutting down trees or in the alternative use of gas for cooking. The alternative to gas will also help in decreasing air pollution.

-

Provision of clean, safe, and, potable water will help to ease domestic tasks for women.

-

The churches to participate in clean-ups and tree planting drives to curb deforestation and to ensure the rubbish dumped during services is managed.

-

More awareness campaigns to be initiated targeting the church and making sure that women in the Johannes Masowe WeChishanu Apostolic churches actively participate so that they can also implement their environmental stewardship roles.

-

There is also a need for education and promotional events to address the environmental challenges. This information dissemination may be done through dialogue and engagement between the church leaders and environmental experts.

-

It is essential that women in the Apostolic Johanne Masowe WeChishanu Apostolic churches be incorporated to champion and lead environmental campaigns. This will enhance their role in the preservation of the earth.

-

Government could increase legislation that governs the operation of churches and how they should participate in environmental conservation.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work.

Ethical considerations

This article followed all ethical standards for research without direct contact with human or animal subjects.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

There was no field research conducted in compiling this article and there are no restrictions on the secondary data presented in this article.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

References

Argawal, B., 2009, 'Gender and forest conservation: The impact of women on community forest governance', Ecological Economics 68(11), 2785-2799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.04.025 [ Links ]

Arora-Janson, S., 2017, 'Gender and environmental policy', in S. MacGregor (ed.), Routledge handbook of gender and environment, pp. 289-303, Routledge, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Barraclough, S. & Ghimire, K.B., 2000, Agricultural expansion and tropical deforestation, Routledge, London. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315870533 [ Links ]

Bhatia, B.S. & Sharma, D., 2010, Sustainable development: Contemporary issues and emerging perspectives, Deep and Deep Publications Pvt Ltd, New Delhi. [ Links ]

Bodjongo, M., 2020, 'Regulations of noise pollution emitted by revival churches and the well-being of neighbouring populations in Cameroon', Environmental Economics 11(1), 82-95. https://doi.org/10.21511/ee.11(1).2020.08 [ Links ]

Bruijnzeel, L.A., Bonell, M., Gilmour, D.A. & Lamb, D., 2005, 'Forest, water and people in the humid tropics: An emerging view', in M. Bonell & L.A. Bruijnzeel (eds.), Forest, water and people in the humid tropics, p. 919, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Chomitz, K.M., Buys, P., Luca, G.D., Thomas, T.S. & Wertz-Kanounnikoff, S., 2007, At loggerheads? Agricultural expansion, poverty reduction and environment in the tropical forests, World Bank Policy Research Report, World Bank, Washington, DC. [ Links ]

De Young, R., 1999, 'Environmental Psychology', in D.E. Alexander & R.W. Fairbridge (eds.), Encyclopaedia of Environmental Science, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Massachusetts. [ Links ]

Death, C., 2011, 'Summit theatre: Exemplary governmentality and environmental diplomacy in Johannesburg and Copenhagen', Environmental Politics 20(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2011.538161 [ Links ]

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), 2007, State of the world's forest, Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations, Rome. [ Links ]

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) 2011, The role of women in agriculture, viewed 16 July 2022, from http://www.fao.org/3/am307e/am307e00.pdf. [ Links ]

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), 2017, Rural women a key asset for growth in Latin America and the Caribbean, viewed n.d., from http://www.fao.org/inaction/agronoticias/detail/en/c/501669/. [ Links ]

Foster, E.A., 2011, 'Sustainable development: Problematizing normative constructions of gender within global environmental governmentality', Globalizations 8(2), 135-149. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2010.493013 [ Links ]

Foster, E.A., 2014, 'International sustainable development policy: (Re) producing secular norms through eco-discipline', Gender, Place and Culture 21(8), 1029-1044. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2013.810593 [ Links ]

Gibson D., Young, L., Chuang, R.Y., Venter, J.C., Hutchison, C.A., III & Smith, H.O., 2009, 'Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases', Nature Methods 6, 343-345. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.1318 [ Links ]

Gozalo, G.R. & Morillas, J.M.B., 2017, 'Perceptions and effects of the acoustic environment in quiet residential areas', The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 141(4), 2418-2429. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.4979335 [ Links ]

Gupta, A., Thapliyal, P.K., Pal, P.K. & Joshi, P.C., 2005, 'Impact of deforestation on Indian monsoon - A GCM sensitivity study', Journal of Indian Geophysical Union 9, 97-104. [ Links ]

Jaggar, A., 2009, 'Transnational cycles of gendered vulnerability', Philosophical Topics 37(2), 33-52. https://doi.org/10.5840/philtopics20093723 [ Links ]

Karimakwenda, T., 2010, Zimbabwe: Power cuts and high costs causing major deforestation, viewed 28 August 2022, from https://www.afrolnews.com. [ Links ]

Kiarie, G., 2020, 'Environmental Degradation: What is the Role of the Church in Environmental Conservation in Kenya from 1963-2019?', Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae 46(2), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.25159/2412-4265/6762 [ Links ]

Lawton, R.O., Nair, U.S., Pielke, Sr., R.A. & Welch, R.M., 2001, 'Climatic impact of tropical lowland deforestation on nearby Montane Cloud Forests', Science 294(5542), 584-587. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1062459 [ Links ]

Littig B., 2017, 'Good green jobs for whom? A feminist critique of the green economy', in S. MacGregor (ed.), Routledge handbook of gender and environment, pp. 318-330, Routledge, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Machingura, F., 2011, 'A diet of wives as the lifestyle of the Vapostori Sects', The Polygamy debate in the Face of HIV and AIDS and the environment in Zimbabwe, viewed 30 July 2022, from https://www.academia.edu/4440379/A_Diet_of_Wives_as_the_Lifestyle_of_the_Vapostori _Sects_The_Polygamy_Debate_in_the_Face_of_HIV_and_AIDS_in_Zimbabwe. [ Links ]

Malaba, J., 2006, 'Poverty measurement and gender: Zimbabwe's experience', in Inter-agency and expert group meeting on the development of gender statistics, University of KwaZulu-Natal, viewed n.d., from https://afri-can.org/CBR%20Information/Poverty%20and%20Gender%20Zimbabwe.pdf. [ Links ]

McLaren, M.A., 2019, Women's Activism, Feminism and Social Justice, Oxford University Press, Oxford, viewed n.d., from https://global.oup.com/academic/product/womens-activism-feminism-and-social-justice-9780190947705?cc=us&lang=en& [ Links ].

McMahon, J., 2020, viewed 20 May 2022, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/jellmcmahon/?sh=34d06ae15819. [ Links ]

Morrow, K., 2017, 'Changing the climate of participation: The gender constituency in the global climate change regime', in S. MacGregor (ed.), Routledge handbook of gender and environment, pp. 398-411, Routledge, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Mujinga, M.K., 2018, The growth of one initiated church in Zimbabwe: Johanne Marange's African Apostolic Church, viewed 28 August 2022, from http://www.taylorinafrica.org. [ Links ]

Mumoki, F., 2006, The effects of the environment today, viewed 28 August 2022, www.panorama.com. [ Links ]

Neumayer, E. & Plümper T., 2007, 'The gendered nature of natural disasters: The impact of catastrophic events on the gender gap in life expectancy 1981-2002', Annals of the Association of American Geographers 97(3), 551-566. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.2007.00563.x [ Links ]

Newsday, 2022, Environmental catastrophe looming on horizon, 03 June, viewed 28 August 2022, from https://www.newsday.co.zw/2022/06/environmental-catastrophe-looming-on-horizon/. [ Links ]

Ozdemir, I., 2008, The ethical dimension of human attitude towards nature: A Muslim perspective, 2nd edn., Insan Publications, Istanbul. [ Links ]

Parker, H., 2017, 'Opinionated analysis development', PeerJ Preprints 5, e3210v1. https://doi.org/10.7287/peerj.preprints.3210v1 [ Links ]

Pearl-Martinez, R., 2014, Women at the forefront of clean energy future. A White Paper of the USAID/IUCN initiative gender equality for climate change opportunities, viewed 28 August 2022, from https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/Rep-2014-005.pdf. [ Links ]

Resurreccion, B.P., 2017, 'Gender and environment in the Global South: From "women, environment, and development" to feminist political ecology', in S. MacGregor (ed.), Routledge handbook of gender and environment, pp. 71-85, Routledge, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Sahney, S., Benton, M.J. & Falcon-Lang, H.J., 2010, 'Rainforests collapse triggered Pennyslavian trapped diversification in Euramera', Geology 38(12), 1070-1082. https://doi.org/10.1130/G31182.1 [ Links ]

Shandra, J.M. & London, B., 2008, 'Women, NGO's and deforestation: A cross national study: Population and the environment', Population and Environment 30(1/2), 48-72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-008-0073-x [ Links ]

Smith, N. & Leiserowitz, A., 2013, 'American evangelicals and global warming', Global Environmental Change 23(5), 1009-1017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.04.001 [ Links ]

Stromquist, N.P., 2001, 'What poverty does to girls' education: The intersection of class, gender and policy in Latin America' compare', A Journal of Comparative and International Education 31(1), 39-56. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057920020030153 [ Links ]

Sze J., 2017, 'Gender and environmental justice', in S. MacGregor (ed.), Routledge handbook of gender and environment, pp. 159-168, Routledge, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Tabari, P., Amini, M., Moghadami, M. & Moosavi, M., 2020, 'International public health responses to COVID-19 outbreak: A rapid review', Iranian Journal of Medical Science 45, 157-169. [ Links ]

Taylor, B. & Kaplan, J. (eds.), 2003, Encyclopedia of religion and nature, Continuum, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Thomas, G., 2011, 'A typology for the case study in social science following a review of definition, discourse, and structure', Qualitative Inquiry 17(6), 511-521. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800411409884 [ Links ]

United National Environment Programme (UNEP), 2016, Global gender and environment outlook, viewed 28 August 2022, from https://www.unep.org/resources/report/global-gender-and-environment-outlook-ggeo. [ Links ]

Van Kooten, G.C. & Bulte, E.H., 2000, The economics of nature: Managing biological assets, Blackwell Publishers, Malden, MA. [ Links ]

Van Marle, K. & Bonthuys, E., 2007, 'Feminist theories and concepts', in E. Bonthuys & C. Albertyn (eds.), Gender, law and justice, pp. 15-49, Juta Legal and Academic Publishers, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Walker, G., 2017, Environmental Justice: Concepts, Evidence and Politics, Routledge, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Xiao, C. & McCright A.M., 2017, 'Gender differences in environmental: Concern sociological explanation', in S. MacGregor (ed.), Routledge handbook of gender and environment, pp. 169-185, Routledge, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Zimbabwe Newspapers, 2013, 'Deforestation looms in Africa', The Sunday Mail, 25-31 August 2013, Herald House, Harare. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Priccilar Vengesai

pvengesai@gzu.ac.zw

Received: 30 Sept. 2022

Accepted: 27 Jan. 2023

Published: 30 May 2023

Note: Special Collection: Religion and Theology and Constructions of Earth and Gender, sub-edited by Sophia Chirongoma (Midlands State University, Zimbabwe) and Linda Naicker (University of South Africa, South Africa).