Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

HTS Theological Studies

On-line version ISSN 2072-8050

Print version ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.79 n.2 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v79i2.8341

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Pre-Islamic religious motifs (550 BC to 651 AD) on Iranian minor art with focus on rug motifs

Abouali LadanI; Jake KanerII

ISIVA School of Design DeTao, Shanghai University of Visual Arts, Shanghai, China

IINottingham School of Art and Design, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, United Kingdom

ABSTRACT

This article reviewed the influence of pre-Islamic religions such as Mithraism and Zoroastrianism on decorative elements of ancient Persian rugs. The article then evaluated the effect of the Islamic religion on Persian rugs. This was examined through extant evidence from pre-Islamic empire artefacts and publications in Persian carpet history, iconography and religious studies. Using spiritual motifs on some ancient rugs results from the important position of rugs in ancient Iranians' lives. Believing the existence of religious motifs on Persian carpets is because the first carpet in history (Pazyryk) was attributed to the ancient Achaemenians, decorated with symbolic motifs from Mithraism and Zoroastrianism. Pazyryk shows how rug-weaving evolved during the Achaemenids, and it represented spiritual foundations through visual concepts. This article reviewed the symbolic Persian rug motifs from ancient religions through Pazyryk, with support from museum collections. With the emergence of religions, these effects are seen in all aspects of life, including the production of rug design.

CONTRIBUTION: The main contribution of this research was that it investigated the effects of religion on Persian art focusing on the Persian rug. The findings showed that religion had directly influenced the decorative motifs of the Persian rug among high-class families that might have cascaded into visual elements found on commoners' rugs

Keywords: Iran; pre-Islam; ancient religions; Persian rug; decorative motifs; mithraism; zoroastrianism.

Introduction

Lack of evidence in the reviewed literature regarding the relation between rug design, the religious purpose behind its symbolic motifs, and a limited number of surviving rugs like Pazyryk and mats found in Shahr-Sokhte, make this topic challenging to study. The influence of the Islamic religion on rugs and other Iranian arts was evident, although religious influence could vary in different forms of art. Nevertheless, remained evidence provides valuable information about the importance and influence of the ancient decorative motifs on ancient Persian rugs (Panjebashi & Najibi 2022). Although these survived, examples could help with some valid conclusions about how the pre-Islamic religion could have reflected on the ancient Persian carpets and the creation of its patterns. In order to understand the connection between rug design elements and Iran's ancient religions, it is necessary to look at the religious elements in other forms of art of that time that have survived, such as illustrations (drawings) and decorative forms of architectural components (stone carvings).

Problem statement

This review research focuses on the influence of religion on pre-Islamic carpet designs, which were prevalent during the beginning of the Achaemenid period (550 BC) through to the end of the Sassanid period (651 AD).

The main intention of rug production at that time was to provide comfort, show wealth (status) and, as considered in this article, demonstrate its position in cultural standing (burial ceremonies). In this study, rug design motifs of the periods mentioned above are reviewed together with other handicraft forms to determine the type of rug motifs and symbols employed to decorate rugs with their spiritual meaning in the overall design (geometric designs).

Research background

The tendency to create art as a form of cultural production is one of the inherent traits of human beings, as can be seen in the extant artworks from ancient times to the present. In Iran, artworks reflect cultural, traditional and religious beliefs. The quality of the Persian rugs and their motifs show the importance of these motifs culturally, from geometric forms in ancient times to advanced and complicated spiral forms on rugs. However, the literature search reveals limited work on this article's subject, making it a potential area for further work. Religion and art are mutually reinforcing, with their long history of engagement. Religion has used art to explain its spiritual and inexpressible aspects, such as miracles and other unexplainable events, which has assisted art in growing as a vehicle to express religion's spiritual principles and concepts.

Scholars and their literature show that the link between religion and art is well established as a discourse (Afrogh & Barati 2013; Apostolos 2004; Moradi & Staishi 2016). Reflecting religious beliefs in arts and crafts through symbolic motifs expressed by Iranians' spiritual values, and decorative motifs used in rug design is not an exception. However, many publications in the field of the history of the Persian rug and its design system, which were reviewed in this study, did not discuss the effect of religion on the art of rug design. This article, therefore, aims to fill this gap by exploring the religious beliefs on remaining pre-Islamic rug designs in Iran. This topic is vital because Persian rugs are recognized as one of the essential and important Persian crafts and have been used in the interior design of homes of Persian royal families and commoners throughout the country's history.

Research questions

The five lines of inquiry that this study have identified are the following:

How were rug designs and religion connected in ancient Iran? This was identified by Rahimifar (1996), who recognised the need to understand the connections between art and religion.

How did pre-Islamic empires show their religious beliefs? Mithraic and Zoroastrian beliefs in the pre-Islamic empire were represented in symbolic motifs as a design structure in Persian mythological culture, such as in carpet designs (Damavandi & Rahmanzadeh 2014).

What was the role of religion (Mithraism and Zoroastrianism) in the creation of rug motifs? Author Maryam Rajabi identifies that a gap in knowledge exists here, as the interpretation of rug motifs appears to connect with religious symbols, but the meaning of such designs is not fully understood (Rajabi 2018). Author Mohammad Nasiri discusses this question in limited depth (Nasiri 2006). This literature has not considered this issue, so it is worthy of study for this work.

Are there any surviving rugs in existence that the study can investigate? The two surviving rugs identified for this study are located at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, and the State Heritage Museum, Russia.

Method

The main source of information for this research was attained from literature, publications in the field of religion and art, and extant carpets, because of the lack of original and remaining evidence. The following methods were used to source and analyse the data to produce the results: mixed sources have been selected to provide descriptive research methods to increase and understand underpinning knowledge, sourced through online archival searches and through observing the extant Persian artworks, such as architecture, engravings and rugs and fabric designs left from Pazyryk and Achaemenid clothing designs. Other sources come from various forms of literature, including monographs, published articles and books related to the Persian carpet history and ancient religious artworks which their decorative and symbolic motifs left on the architecture and other forms of handcrafts from ancient times in Iran, which are studied and explained by archaeologists and scholars. Moreover, academic websites which examine the role and position of religion and its impact on various forms of art of different pre-Islamic periods, focusing on rug design and its decorative motifs, were also used.

Scholars have engaged with research on religion's impact and its relation to art. Publications, including 'Art in religious mourning in Iran' (Farbod 2008), explain the effect of religion and religious mourning ceremonies on the emergence, growth and evolution of artistic phenomena, which should be considered when examining the only remaining rug (Pazyryk), found in a burial place, showing its connection with the religion of that time. The gap in knowledge that has been identified on the impact of religion on the art of ancient Persian carpets is evident, and this research tries to provide sufficient information and analysis on the most important Persian rugs (Pazyryk) in this regard.

Moradi and Staishi (2016) examine the unique capabilities of art comparing to different religions and beliefs. These publications examine religion and its relationship with artistic forms, recognising how they are brought closer together, enabling the intended outcomes of perfection and true peace to be achieved. This points to the drivers of religious beliefs in crafts like rugs. Some publications study the Persian rug motifs, tasking a cursory look at some motifs with religious backgrounds. Jalilian and Ahmadpana (2012) explore the animal motifs of the city of Hamadan in Iran and, according to the available sources, provide an overview of the source of the motifs from the perspective of myth and religion. The above-mentioned article reviews a specific region (Hamadan, Iran) and uses vernacular rugs to support the idea that the ancient Iranian rug design was connected with religious and mythical beliefs. Rashadi, Salehi and Nowrozi (2019) examine the role of religious subjects and stories on the carpets of the Qajar period. Other publications study the role of religion on specific arts, such as architecture and metalwork, that indicate the influence of religion (Afrogh & Barati 2013).

Results

The following findings were revealed as a result of the research questions:

The first and only remaining evidence, Pazyryk, shows that pre-Islamic religions (Mithraism and Zoroastrianism) intentionally employed art to express themselves visually to achieve the highest impact on people. Pazyryk, as a remaining example, presents a high-quality rug with borrowed motifs with a Mithraic background; the rug's importance and design in royal activities could be seen. In such a case, using religious motifs on the rug at the funeral was not an accident. As a result, it could be concluded that such motifs were also employed to decorate rugs for religious places and commoners.

In the visual form of religion, artistic motifs are used on different platforms to represent its idea and philosophy. Pre-Islamic art is not an exception and used symbolism in the form of decorative motifs on important platforms that had an influential position in people's lives, such as the motifs placed on architectural walls. Although there is no other rug evidence than Pazyryk to support the importance of rugs in ancient Iran, through the quality in material, techniques and motifs, it is possible to see the rug and its design playing a significant role in decorating religious places.

Because the Pazyryk motifs present elements from Mithraism in burial ceremonies, they support the idea of the importance of the rug and its design among people. Throughout the period in later pre-Islamic and Islamic dynasties, the evidence from miniatures and remaining authentic rugs shows that motifs with religious aspects had become common in rug designs. This could be rooted in ancient pre-Islamic rug designs.

The well-known and only surviving rug is the one known as Pazyryk, with its predominance of Mehr (Mithraic) symbols employed in burial ceremonies, and the mats from graves in Shahr-Sokhte, because they believed in the afterlife.

The impact of religion on art in ancient Iran

To examine the impact of religion on art, an understanding of ancient Iran is essential, together with a familiarity with the period's territorial characteristics and cultural conditions. Persia was located in eastern Mesopotamia with the ruling states Assyria, Acre, Sumer, Babylon and other civilisations, such as Egyptian and Greek. With their extensive and accomplished histories that influenced one another, they connected with Iran through political, religious, cultural and artistic endeavours. This influence was either through peaceful friendship or conflict and war (Farmer et al. 2019). In the past, painting, especially mural painting, was attached to architecture and interior design, just like sculpture.

In pre-Islamic Iran, the Zoroastrian religion, as the most common religion, used art to show the royal family's (especially the King's) spiritual vision to highlight their religious purpose and the nation's culture. The 'high-ranked' is key in this study because of the lack of evidence from commoners. They express religious beliefs and mindsets, customs, communication, solidarity and sometimes differences and contradictions (Majidzadeh 2001; Rahimifar 1996; Razi 2005). Mithra appeared to be a significant deity in Eastern, Indian and Iranian sources, and later, Mithra was placed as a god next to Ahura Mazda. However, its characteristics were never clearly pointed out. Although Mithraism is one of the most influential ancient religions in Iran, in connection with art, it had limited reflection on the works of art of its time. Most of the Mithraic elements such as the lotus flower or swastika were widely used later during the Zoroastrian religion (Afrogh & Barati 2013).

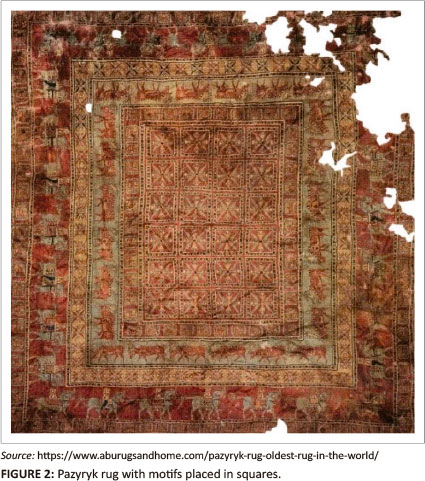

Investigating Pazyryk, the religious source of rug motifs, and exploring architectural design as one of the primary artistic reflections of society can lead to a better understanding of the relation between decorative motifs and religion. Reviewing the Mithra temple (Figure 1) plans and location provides background information about rug design motifs. For instance, altars (the place for spiritual fire) left from that period show the importance of their spiritual ritual practice, designed as square platforms for the fire (altar) in Mithraic temples, which were symbols of a window to the real world ('afterlife' world). The path to God could implant the idea that placing all the Pazyryk decorative motifs in a square (Figure 2) could represent passing through worldly life and moving towards God and eternal life.

Another well-known Mithraic motif used in many forms through different years in Iran is 'Mithra' [swastika]. One example shows this motif on a necklace found in Clores Gilan, Iran. The story behind this which makes the motif important is explained in the Avesta; Mehr, the superior god, rode around the world on a chariot looking like a swastika, scattering light and fighting with darkness (Razi 2005).

Ancient Iran's culture and art should be sought in the religion of Zoroastrianism (6th century BC), as the study of ancient Iranian art during the historical periods from the Median era (678-549 BC) to the end of the Sassanid period (224-651 AD) shows a deep connection between Zoroastrian religion and the art of that time. Images and symbolic motifs in various arts, such as architectural forms, paintings or carved images of Ahura Mazda on the throne of kings and nobles, are derived from traditional and allegorical features related to Zoroastrianism (Figure 3).

The art of this era was a combination of the art of various tribes, combined methods and forms borrowed from foreign cultures (mixed-culture art). The Achaemenids enhanced their art by adequately using a mix of different nations' art styles and techniques and employing all these artistic manifestations into one format. This brought foreign artistic elements to sit next to the Zoroastrian visual characteristics and reflects the Persians' cultural beliefs.

The ancient visual evidence that survives from ancient Iran, from the Achaemenid to Sassanid eras, was based on Zoroastrian theology, cosmology and anthropology. However, it is important to point to the source of these motifs, with the majority presenting the importance of Zoroaster and Ahura Mazda through the lives of the kings. The repetition of the Avesta's themes and symbolic motifs has been a typical design structure in Iran's national and mythological culture that has been established over time (Damavandi & Rahmanzadeh 2014). Most of the popular themes are polarised, reflecting the opposition between good and evil, truth and falsehood, darkness and light. In the lives of the people who had preserved this religion for a long time, not in writing but orally and visually, these artistic-religious symbols changed their purpose to propagate, publish and transmit this religion (Masoumi 2014). For instance, the influence of the symbolic form of good and evil continues to be used today in Iran during the current Islamic era in symbolic artworks and political matters.

Through the surviving advanced arts, carpet weaving was one of the prominent manifestations of Persian art during the Achaemenid period. This art was not widely studied due to the destruction of Persian carpets at that time. However, in the late fifties, the discovery of Pazyryk (a 1.2 m2 carpet discovered along with other exquisite works in the Siberian ice) revealed new information for studying Achaemenid art. This rug's design illustrates the skill and mastery of the Achaemenid weavers, showing the long tradition of Iranian weaving of carpets, dating back approximately 2500 years (252-238 BCE). This extant rug example from this time depicts the progress achieved by the Achaemenid artists, demonstrated in their highly skilled handwork.

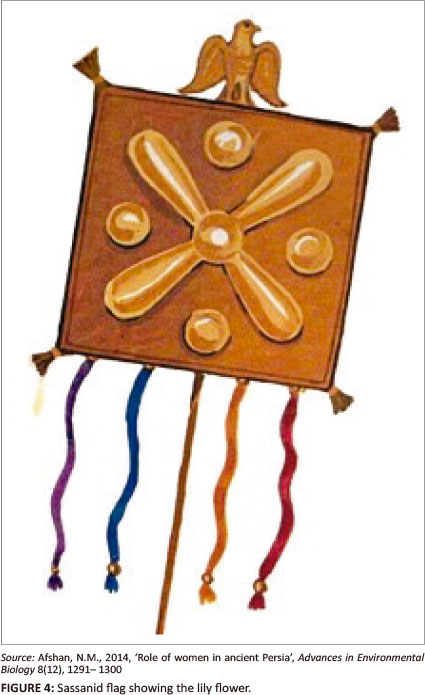

Later, the Parthians (247 BC - 224 AD), with many similarities with the Achaemenids, including a flourishing level of art production, worshiped the Zoroastrian deities such as Ahura Mazda, Anahita, Atash and Izad Mehr. The culmination of religion and art in ancient Iran is seen mainly in the art of the Sassanid Empire (224-651 AD). Sassanid art is associated with religious beliefs, although it is a continuation of the ancient Iranian arts (Achaemenid and Parthian) and was influenced by various cultural and artistic styles that flowed from the east and west to this art. Although it was a mixed style, it still had its characteristics. For instance, the expansion of semicircular arches with wide openings and congresses on the arch are the features of Sassanid architecture which later continued in the Islamic period. This arch shape later became a part of the rug structure in the Islamic era. One of the common symbols borrowed from the Achaemenids is the lily flower used in the Sasanian national flag (Figure 4).

The rug had an important place in Sassanid culture. Based on the documents and stories, carpet weaving was a popular art in the Sassanid period, with rich visual aspects (Figure 5). According to history, when Hercules, the Byzantine emperor, conquered the palace of the Sassanid King Khosrow II in 628 AD, he found many exquisite and hand-woven fabrics, knitted carpets and embroidered carpets (Nasiri 2006). Some elements in the surviving works of art, such as petroglyphs and metalwork, confirm the importance of carpets in the Sassanid era.

Discussion

Pre-Islamic and ancient Persian carpet design

The origin of the word 'rug' comes from the word 'mat', a primary form of floor covering. Mats were a functional solution when people needed something to sit or sleep on the floor in ancient times. It also became an important part of religious events such as burial ceremonies and later as a prayer rug in the Islamic era. The primary organic materials were reeds, and later wool was also used. Although there is not much textile evidence left from the pre-Islamic era in Iran (the very first evidence is from the 15th millennium BC and earlier, 3000 BC), it may be said that textiles of any kind were elementary materials of people's lives prior to settling down in villages.

Religion had been exploiting the craft of the Persian carpet and its influence on the Iranian lifestyle to transmit philosophical insights and mysticism at the level of society (Apostolos 2004; Panjebashi & Najibi 2022) to a later time when the rug was designed to use in Muslim mosques. The use of rugs started with a mat made from natural reed, and later with improvements in carpet technology and the introduction of carpet dying, colours became a vital part of carpet design next to geometric motifs taken from nature. The impact of these symbolic motifs on art and people has been so significant that today they continue to be used to decorate many craft objects made for everyday life, as well as rugs and textiles.

Key features that represent religion in Iran's rug design summarized in motifs, rug design structure, and composition that remained from ancient reflect Iranian beliefs. These features have been used over time (sometimes with minor updates and receiving new motifs in their composition) next to the carpet design structures seen in all of Iran's eras, from pre-Islamic times (559 BC) until the present day explained below:

Religious symbolism is a prominent feature in rug designs.

Ancient rug design elements were usually evident, as geometric forms were taken from their living environment, myth and culture, representing the essential and critical aspects of their life, including religious beliefs and related ceremonies such as burial ceremonies.

Using a square or rectangular frame (as a part of the rug design or the final rug shape) illustrates the primary rug structure in ancient times. These frames show the four geographical directions and ancient climates.

The design's principle of symmetry and balance is emphasised to represent unity.

The design layout of each carpet has two main parts, namely the central area, symbolising monotheism, and repeated edges representing unity and, at the same time, multiplicity.

Elements of Mithra in the Persian rug: Pazyryk

Investigating the relation between rug design motifs and religion goes back to the time of Mehr (Mithra in Sanskrit), the god of light and the Sun and one of the ancient Aryan gods from the 14th century BC in Iran, to approximately the 6th millennium BC, with followers worldwide (Rajabi 2018). The worship of Mithra in the Western world, especially in Greece and Rome, has been subjected to biased and one-sided perceptions because they were not on good terms with Iran. Because of this situation, attention to the Iranian god Mithra had not been considered necessary in ancient times, and Mithra started to be mentioned in written documents from 136 AD onwards. As a result, many motifs rooted in Mithraism continued with the Zoroastrians, known as Zoroastrian motifs, even the motifs encountered on the Pazyryk carpet.

The following sections describe the design elements of the Pazyryk and explore the relationship between motif and religion.

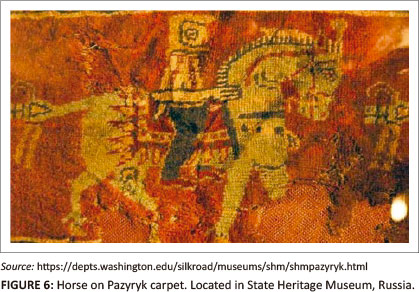

Twenty-eight motifs of horses, depicted on the edge of the Pazyryk rug, show this animal's importance (Figure 6). The horse symbolised the Sun and the gods in the Aryan religion (Mithraism). The gods of myth were embodied in the form of white horses to fight the enemy or reveal their existence in the eyes of the people (Nasiri 2006). Bahram, the Zoroastrian god, was embodied in three different body forms when he appeared, and in his third incarnation, he appeared as a white horse. The horse in ancient myths also represented the mythical gods' chariot (Majidzadeh 2001).

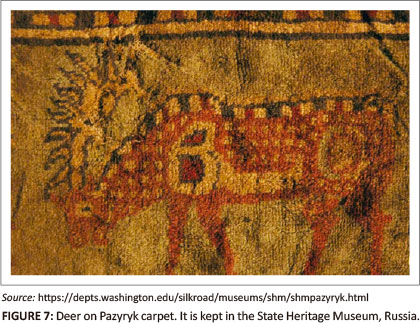

Pazyryk’s deer, like the motifs of horses and their riders, were arranged in a very precise order and in the form of a ritual parade (Figure 7). The symbol of the deer in the mythology of ancient Iran was a form of Anu, the celestial god of Mesopotamia (Hall 1995).

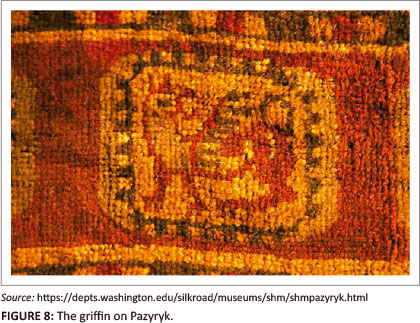

The griffin (Figure 8) was a mythical creature with an eagleshaped head, wings, front legs and lion-shaped hind legs, created by Elamites as the protector of temples, being repeated 120 times on Pazyryk (Polosmak 2015). This mythical creature was accepted as a symbol of a powerful, extraordinary and alert creature in Iranian mythology. In ancient times, this creature was a symbol of divine power (Damavandi & Rahmanzadeh 2014).

Lotus

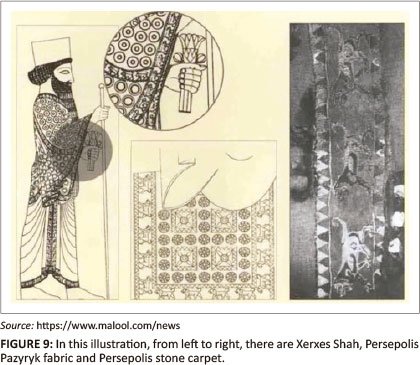

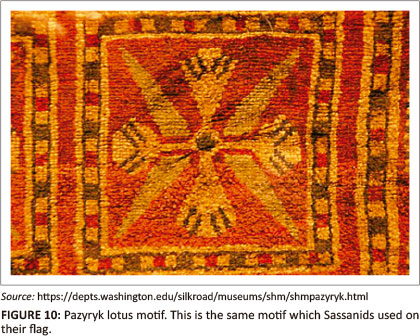

The lotus flower is closely related to the Mehr religion and ancient Iran. It symbolises the royal family (Figure 9). The goddess Anahita was the source of all water on Earth, fruitfulness and fertility for all phenomena, according to the belief of the ancient Iranians. In some of Mehri's works, it is shown that Mehr is born in water and is placed on a water-lily flower (lotus flower) (Damavandi & Rahmanzadeh 2014). In this way, the lotus is closely related to the ritual of Mithraism (it is repeated among the 24 squares on the long edges of the Pazyryk rug). Considering that the lotus flower on Pazyryk was designed in the centre and the importance of this flower in Mithraism and among people shows that the Pazyryk rug reflects a religious view and design for a specific and important spiritual event (Figure 10).

These motifs resemble ancient rug design systems using geometric forms in square and/or rectangular frames and repetition. Each motif refers to ancient Mithraism (and later Zoroastrian religion in the Achaemenid era). Single motif repetition reflects the universe's unity and monotheism, from repeated lotus flowers in the center of the rug, to horses and their riders representing this philosophy. Mithra (the god of light), Mithraic beliefs and its myths.

Conclusion

Art has been affected by religion in various periods. Islamic symbolic motifs and calligraphy were added to Iranian art, especially into the rug design after the Islamic period of Iran. This review research focuses on the influence of religion on pre-Islamic carpet design, from the beginning of the Achaemenid period (550 BC) through to the end of the Sassanid period (651 AD). From the beginning of creation, humans have always sought to worship and praise a higher power to compensate for their spiritual shortcomings. Hence, in most of the works left from the Palaeolithic period, and later in the lithographs and historical-artistic surviving works, this tendency to praise the supernatural power and the desire to worship God in any form and type is visible.

Persia, which is considered one of the earliest human civilisations, is no exception to this rule. The connection between religious beliefs and rug design is evident through the surviving examples. Furthermore, the art of carpet weaving, with its traditions in Iran's culture and civilisation, undeniably shows this relationship through symbolic forms and motifs. They frequently reflect religious beliefs by selecting auspicious flora and animal representations taken from religious literature to celebrate creation and the power of the ancient God. Critical to this study have been surviving items of evidence (the mat and the rug), as well as the wall carvings which provide examples of the impact of religious symbolic motifs on the art of rug design.

Furthermore, in ancient Iran, these forms' iconic visual motifs and symbols demonstrate that religion has been represented in many arts-based disciplines. This religious influence on rug design and production demonstrates the strong religious beliefs of royalty. Zoroaster and Ahura Mazda religious elements, such as animal figures and mythological symbols, are highlighted next to the brilliant choice of colour on this rug design.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

Authors' contributions

A.L. wrote the original draft; J.K. reviewed and edited.

Ethical considerations

This article followed all ethical standards for research without direct contact with human or animal subjects.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

References

Afrogh, M., & Barati B., 2013, 'Elements and symbols of Islamic identity in Iranian carpets', National Studies Quarterly 53(1), 67-79. [ Links ]

Afshan, N.M., 2014, 'Role of women in ancient Persia', Advances in Environmental Biology 8(12), 1291-1300. [ Links ]

Apostolos, C., 2004, Religion and the arts: History and method, vol. 100, pp. 11-23, Transl. F. Sasani, Binab Magazine, Tehran. [ Links ]

Damavandi, M. & Rahmanzadeh, S., 2014, Comparative study of Mithraic and Izadi religions, pp. 117-142, Mystical and Mythological Literature. [ Links ]

Farbod, M., 2008, Art in religious mourning in Iran, Iranian Culture No. 11, Tehran. [ Links ]

Farmer, E.L., Hambly, G.R., Kopf, D., Marshall, B.K. & Taylor, R., 2019, Comparative history of civilizations in Asia, vol. 1, Routledge. [ Links ]

Hall, James. 1996. Illustrated Dictionary of Symbols in Eastern and Western Art. 1st paperback ed., Icon Editions, New York. [ Links ]

Hodk, M.Z. & Khalili, M., 2022, 'An analysis of Iran-Armenia relations using security theories (Copenhagen School and Neoclassical Defensive Realism Theory)', Specialusis Ugdymas 1(43), 5765-5786. [ Links ]

Jalilian, N. & Ahmadpana, S., 2012, 'The effect of religious and mythical beliefs on the rural carpets of Hamedan,' Iranian Journal of Hand Woven Carpet 8(22), 56-59. [ Links ]

Majidzadeh, Y., 2001, History and civilization of Mesopotamia, Tehran, vol. 1, pp. 93-104, University Publishing Center, Tehran. [ Links ]

Masoumi, G., 2014, hMehr Encyclopedia of ancient world myths and mirrors, vol. III, p. 78, Surah Mehr, Tehran. [ Links ]

Moradi, S. & Staishi, Z., 2016, 'The relationship between art and religion', in The second annual conference on architectural, urban planning and management, Tehran, July 18, 2023. [ Links ]

Nasiri, M., 2006, The legends of the immortal carpet of Iran, 1st ed., p. 45, Mirdashti Cultural Center, Tehran. [ Links ]

Panjebashi, E. & Najibi, N., 2022, 'A comparative study of the Menhir of the Shaharyeri historical site located in Meshginshahr of Ardabil Province and the Saint-Sernin Aveyron in the South of France', The Monthly Scientific Journal of Bagh-e Nazar 19(111), 75-90. [ Links ]

Polosmak, N.V., 2015, 'A different archaeology Pazyryk culture: A snapshot Ukok, 2015', Science First Hand 42(3), 78-103. [ Links ]

Rahimifar, A., 1996, 'Solidarity of religion and art in the realm of history', Hozor 16, 45-56. [ Links ]

Rajabi, M., 2018, The story of Iranian carpet, p. 89, Ofogh Publication, Tehran, Iran. [ Links ]

Rashadi, H., Salehi S., & Nowrozi H., 2019, 'A study of the function of religious subjects in the pictorial carpets of the last century', in First international conference on Religion, spirituality and quality of life, 2020, Tehran. [ Links ]

Razi, H., 2005, Iranian religion and culture before the time of Zoroaster, p. 90, Sokhan Publications, Tehran. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Abouali Ladan

ladanabouali1@gmail.com

Received: 29 Nov. 2022

Accepted: 19 Jan. 2023

Published: 24 Mar. 2023