Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

HTS Theological Studies

versión On-line ISSN 2072-8050

versión impresa ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.79 no.1 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v79i1.8923

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Faithful hiring: An exploration of pastoral hiring within the Canadian Evangelical Church

Christopher R. Bonis; Marilyn Naidoo

Department of Philosophy, Systematic and Practical Theology, College of Human Science, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The pastoral role is a significant leadership function within the global evangelical church and is critical to the ongoing health, nurturing and spiritual development of the church and its members. There is limited literature and reflection on hiring for the church, yet the selection of a pastoral leader is more than an employment exercise as it involves important Christian values, perceptions and priorities of the church and the denomination. This article records a study on pastoral hiring process within a significant evangelical denomination in Canada. It uses a descriptive, multiple case-study approach involving four churches engaged in a pastoral search process. Findings revealed a convergence between church practices and typical organisational processes with pragmatic strategies for hiring decisions. In a secularising society of Canada, it is especially important that the church critically reflects on maintaining scriptural values on its hiring practices and not be shaped by the commercially driven business context to distinguish ethical practice and maintain its Christian witness.

CONTRIBUTION: This study provides new knowledge in the field of congregational studies on a much-neglected area of Christian practice, motivating for critical reflection and scriptural integrity within pastoral hiring processes.

Keywords: pastoral hiring; church practices; leadership development; praxis; secularisation; church administration; church leadership; biblical principles.

Introduction

In previous decades, the evangelical church expressed a value and placed emphasis on character in the recognition of pastors. 'Evangelical' here is understood as a diverse group adopting and giving expression to Bebbington's four pillars that involve biblicism, conversionism, crucicentrism and activism (Crossley 2016:122-123). The Bible affirms a priority for and describes aspects of preferred character (1 Tim 3 and Tt 1) for those selected to lead within the church. It is important to note that ordination for ministry is exclusively male in the evangelical tradition sampled and the preference for the complementarian perspective to leadership although females may be leaders within other capacities. It is understood that the various functions and leadership roles for the church are given by Christ as gifts to His church. Despite this normative grounding, there appears to be increasing reports and news articles of significant scandals involving church leaders - both moral and financial (Chamberlain 2021) - that have resulted in many pastors stepping down from their role. Any assessment of these biblical and spiritual values such as upright character, personal integrity, not driven by materialism, having a good reputation, etc. are all values that are marginalised in favour of pursuing quick ministry results and growth. Increasingly, concerns are being expressed about leadership in the church and the impact of secular forces upon the church and the pastoral role (Sims 2011:166). These concerns extend from a distancing of ministry from the Scriptures, the reduction of the pastoral role, calling and competencies to a focus on keeping busy with the affairs of the church (Lischer 2005:168). Dreyer (2015) suggests that apart from the external circumstances that put pressure on the church such as finances or attendance, a primary contributor to the crisis of the church is 'the church not being able to be the church' (p. 1). In this, the church may be unaware of what it is to be and do and not be alert to expediency in various practices of the church, including pastoral hiring processes.

The pastoral role is a significant leadership function within the church and is critical to the ongoing health, nurturing and spiritual development of the church and its members. Spiritual sensitivity and discernment on the part of those responsible for pastoral selection and hiring are needed. The selection of a pastoral leader is more than an employment exercise as it involves an important spiritual component of discernment and identification of a leader who is 'instrumental in the spiritual and numerical growth of the church, by equipping members in their relationship with God, one another and those within their communities' (Joynt 2017:2). It speaks of the values, perceptions and priorities of the church and the denomination. Spiritual values influence church practices and are needed in ongoing reflection; Reimer and Wilkinson (2015) speak to the realities within the tradition:

The evangelical subculture … seem to believe that with the right research, and the correct techniques, and the correct business model, good leadership, and attractive buildings and programs, they will grow and succeed. Thus, practitioners will often read books … hoping to find some knowledge from science that will help them 'succeed' using the same definition a secular business might use. Unfortunately, we wonder if we are unintentionally feeding a tendency within evangelicalism that encourages practitioners to priorities questions like 'What can I do to grow my church?' … By its own logic, evangelicalism prioritizes the Bible as the final authority, and Jesus as the primary example - not numerical growth. Their ecclesiology suggests they first ask different questions, like 'What does it mean to be a faithful witness of the reality of Jesus?' Sometimes the answer to that question may require the church to do things that will not add to its numerical or budgetary success. (p. 208)

Within the evangelical church in Canada, the pressures of secularisation including theological liberalism and materialistic individualism and the feeling of marginalisation by the church are common (Stiller 1991:202). Additional factors are increased religious pluralism, managing religious and ethnic diversity in public institutions, consumerism and the focusing of attention on individual rights and away from religion and any common ideology for the Canadian identity (Reimer & Wilkinson 2015:46, 48). According to Reimer and Wilkinson (2015:48), 'the net result of these Canadian cultural and demographic changes is declining institutional Christianity in Canada'. Consumerism and individualism have seen a shift within churches and on what a church might offer (Bruce 2006:36-37). Individuals become the focus of the church and may make subjective determinations of the shape of church practices based on felt needs and experiences (Beyers 2014:9; Branson & Martinez 2011:154-160). As a result:

Canadians are more likely to leave a congregation if they do not get what they want, and 'shop' for religion elsewhere. They are demanding consumers of religion, evaluating the religious 'products' presented by clergy to see if the suit their needs. Clergy calls for institutional commitment often fall on deaf ears. Individualism results in less deference to clergy. (Reimer & Wilkinson 2015:136)

With these societal challenges, one might question how these factors might influence or impact the practices and processes of the church. 'Practices, then, contain values, beliefs, theologies and other assumptions which, for the most part, go unnoticed until they are complexified and brought to our notice through the process of theological reflection' (Swinton & Mowat 2006:20). As practices are value-laden shaped by a commercially driven business context, using these theories has moral consequences in hiring pastoral leaders and shapes the moral outlook of those who practice them. There is value in questioning and reflecting upon practices, especially when management tools from the secular world are used uncritically and replace theological perspectives or divine realities. This study problematises the area of pastoral hiring within church practice; with limited literature, it seems to be treated as peripheral to other significant areas of practices like preaching, worship and pastoral care.

The research methodology

This study sought to explore the pastoral hiring process of the evangelical church in the Canadian context to understand the various institutional factors that shape the process, consider the values demonstrated and reflect on the implications for church practices. This practical theological study was qualitative using the 'descriptive-empirical task of practical theological interpretation … attending to what is going on in the lives of individuals, families, and communities' (Osmer 2008:34). This study involved multiple cases to observe any commonalities and triangulation of the data in order to develop transferability related to the pastoral hiring process (Leedy & Ormrod 2010:137-138; Slevitch 2011:78).

This study used concepts from Olian and Rynes (1984), whose work on organisational staffing from a general perspective provided key elements that helped frame the data collection and exploration in light of what are typical processes for hiring. They identified that all organisations deal with similar issues or characteristics of their hiring process, yet they acknowledge that 'effective organizations may develop very different structures and processes to attain their goals' (Olian & Rynes 1984:171).

The impact of a diverse, shifting culture and the response of an evangelical denomination relative to these pressures provide the basis for this study. A denomination within the evangelical church was selected as this denomination represents a significant entity within the evangelical landscape in Canada. It was identified with strong presence across the country and specifically within the province of Ontario (Government of Canada 2003:6, 17) and represents a large percentage of evangelicals with a strong representation of both urban and rural churches to draw from.

As a primary method of data collection, in-depth, semi-structured interviews were appropriate with a sample that consisted of 15 interviews from four evangelical churches (two urban and two rural churches) that were engaged in a pastoral search process and looking to hire a church pastor. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with denominational leaders and selection-committee members. These selected churches were from the same evangelical association within Ontario, Canada to maintain a consistency in terms of their organisation, doctrines, theology and core identity. The need for both urban and rural was because the backgrounds, religious practices and social context of the rural or small-town sample may be more traditional and conservative and 'contribute to an attitudinal and behavioral differentiation of the urban population' (Glenn & Hill 1977:39-44). Data analysis was through a blend of open coding (Saldana 2016:115) using Atlas.Ti, qualitative analysis software. Within each stage of the hiring process, the data were reconceptualised and themes were created.

It is important to note that hiring practice varies within the different denominational groups within Canada. From a review of in-house documentation, many evangelical church groups are encouraged to follow a process of selection similar to what was used by the denomination in this study (British Columbia and Yukon District: The Pentecostal Assemblies of Canada 2017; Canadian Baptists of Ontario and Quebec 2016), (Fellowship of Evangelical Baptists, Associated Gospel Churches). Some evangelical churches involve a more formal ratification process and involvement at the denominational level (Christian Reformed Church - Pastor Church Resources 2021; The Presbyterian Church in Canada 2019). Typically, those churches with greater autonomy tend to follow a process similar to what has been depicted here.

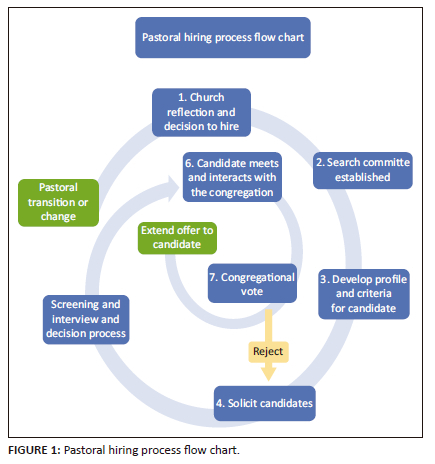

While the study revealed that though the hiring processes followed the typical pattern presented in Figure 1, the findings were focused on unexpected realities - things from the process that stood out or abnormalities where the practices suggested something worthy of more reflection. The following section highlighted some of these findings and interpretations of the seven processes. These generalisations are limited to this denomination and do not necessarily speak to all denominations within the evangelical tradition.

Findings and interpretations: The hiring process

A pastoral change or transition initially occurs within a church, which triggers the beginning of the process towards the hiring of a new pastor. A typical pastoral hiring process involved seven consistent steps, namely:

Church reflection and decision to hire

Establishment of a search committee

Develop profile and criteria for a candidate

Solicit candidates

Screening and interview and decision process

Candidate meets and interacts with congregation

Congregational vote

Following a successful vote and acceptance of a pastoral candidate by the congregation, a formal offer is extended to the candidate.

Church's decision to hire

In this first step, the church typically engages in a period of self-reflection or assessment, involving congregational evaluations of their health; why their pastor left or was dismissed and other relevant issues that could impact future hiring decisions; a review of the church's mission and vision; board meetings and other input based on which the decision to initiate a pastoral hiring process was. What appeared to be a significant challenge for the sampled churches, was its inability to objectively look at itself and answer questions about their: structural and organisational health; clarity around mission and vision and accuracy in assessing the actual needs of their church. Often, the decision to engage in a process to search for their next spiritual leader was made prior to such reflection or addressing of key areas, often resulting in recurring challenges for the church.

'So, going into this all of the millennials who have grown up in the church that has been broken time and time again … that affected our decision in how we were going to pick somebody because we did not want to rush into anything. People wanted to take the time to fix some of those problems before we hired somebody new. We did not want someone coming into the toxic atmosphere of people being angry at the elders.' (Urban Search Committee member's response, C1U1SP1, Female, 20's)

Apart from the identified needs of understanding why a church exists and where it is going, and an acknowledgement of problems that can exist within the church, there is an indication of a pastoral search process that has been historically rushed, leading to a cycle of problems, brokenness and hires that have not worked out.

Search committee established

In this stage, a group of people in the local sampled church are appointed to execute the work of selecting a leader. Popularity, business acumen, previous experience, knowledge of various church ministries and human resource skills were all mentioned as reasons for possible inclusion on a search team. The human resources task, at least as far as some of the skills needed for interviewing and selecting from various job candidates, could be helpful. However, the task of assessment and discernment regarding such things as fit, gifting or calling when it comes to selecting a church's pastor is not limited to skills alone but appropriately resides within a spiritual realm.

'[I]n order for the search committee to understand the specific doctrinal criteria that we want the next guy to believe and teach and represent - that means everyone on the search committee needs to understand that … we have had some frank conversations about that and you have to be a little sensitive to people that may or may not agree with that but now have to understand that I am representing not just myself and my own personal beliefs but I am representing what the church stands for. That I would say was something significant we have had to deal with.' (Rural Search Committee member's response, C3R1SP2, Male, 40's)

Theological and doctrinal unity, or even clarity, at least as far as serving on a search committee and representing the church to candidates can be a challenge. Identifying and acknowledging the potential of the lack of spiritual depth of those serving on a pastoral search committee raises several questions related to leadership development, ongoing discipleship and where the repository of spirituality and theological insights are held and maintained. If they primarily reside solely within the pastor, then it can be a challenge when a congregation is without one and engaged in a search process.

Develop criteria and a profile for the candidate

As the pastoral search process cycle continues, the sampled church must inevitably establish a clear criteria and profile that they hope to fill with a suitable candidate. Following the latest trend for naming the position being hired, or amalgamating favourable points from several other church's job descriptions seems to indicate that there is a lack of clarity around several elements related to the church's role in general and the specific ministry focus and pastoral needs of a church:

'We have a job description, but we have made it clear to the candidates that it is a job description that perhaps Jesus himself could not fill which is pretty typical, but we try to cover all the bases with what we think is important.' (Rural Board member's response, C4R2BP1, Male, 50's)

It was found that while an exhaustive criteria and preferred pastoral profile may ensure that every element is included, as noted by the above quotation, there is a general understanding that such a job description is excessive and does not accurately reflect a realistic expectation or understanding of the church's priorities, mission and needs. If it is an accurate expectation based on needs, then it would admittedly be a challenge to find a candidate to meet all the expressed needs and cover everything within the church. This presents hiring criteria and a pastoral role that is likely destined to result in no suitable candidates or else a quick pastoral turnover and another search.

Solicit pastoral candidates

It was established that once the pastoral search criteria were established, the next step was to promote the opportunity and to solicit potential applicants to be considered for the position and engage in the selection and hiring process:

'[A] lot of the pastors I have been talking to said that you will not find a pastor that will be leading your church that way. Most of the time you will have to go into the church and really woo that Pastor over and place that seed of questioning in their minds and prompt them and say "Don't you think you should be moving already"? … So, pastors were advising us to get pastors from other churches … That was how our old Pastor left to go somewhere else. For two years that church went after him feverishly, so he believed that was the way that we would get our pastor … It is funny but it actually happens more often than not. That was how our former Pastor moved over and our other pastor too - they went after him and then he moved.' (Urban Search Committee member's response, C2U2SP1, Male, 30's)

In Canada, within the evangelical church, there is a challenge to find suitable candidates (Paddey 2018) or even any candidates at times, with the numbers of pastors retiring or leaving pastoral ministry reported to be on the rise (Reimer & Wilkinson 2015:134-139). It was found that while this appears to be a difficulty faced by many churches, it was nevertheless surprising to see the concept of pastor 'hijacking' being advocated by pastoral leaders as an acceptable practice.

Screening and interviewing and decision-making

This step is one of the most significant parts of the pastoral hiring process and involves the screening of potential applicants according to established criteria, then choosing to interview some to get a more thorough, first-hand perspective and to begin to 'know' the candidates. Assuming all goes well, a preliminary decision could be made to focus on particular candidates and go more in-depth:

'… anyone applying had to complete a profile. It is something that is very exhaustive but to their credit they are very thorough … We were not as concerned about all the details of the profile as we were just concerned with them signing it. That was it. Because we believed in the totality of our doctrines that any deviation from that really would be not what the church doctrine is beholding to.' (Urban Search Committee member's response, C2U2SP1, Male, 30's)

It was established that for the screening process to be reduced to signatures on a profile that indicates that a candidate agrees with a code of ethics, a statement of faith and would resign if their doctrinal position changed, it appears to assume that anyone signing such a document is a suitable candidate and meets all the criteria and qualifications listed. The same documents contain a disclaimer on the first page that any information cannot be verified or authenticated as accurate. Interestingly, aside from one passing comment by an interview participant that biblical qualities were assumed, there was no mention or inclusion of biblical character qualities within the screening or assessment process:

'… we ran into that problem in the past where we had strong disagreement by one of our members. They ended up being the right one. But because the majority of the search committee felt this was the ideal candidate what do you do?' (Urban Board member's response, C1U1BP2, Male, 50's)

It is a challenge when a screening, interviewing and decision-making process is determined by a majority and based upon opinion rather than spiritual consensus of discernment and a peaceful unity (James 3:17). This appeared to also factor into earlier considerations within the process as an area to be reflected upon as such qualities were not always in evidence.

First encounter of candidate with the congregation

At this stage in sampled churches, it was found that at a minimum, a pastoral candidate preaches on a Sunday morning and participates in a question-and-answer session and an informal gathering with the church, prior to the church voting to decide whether to hire them as their new pastor. The amount of time dedicated to this aspect varied but was consistently reduced to a short time frame, often just a weekend and typically focused on external aspects of family, role, church life and expectations.

The congregation decides

After an initial time of contacting the candidate, the sampled congregation now decides by casting their vote to affirm a candidate as being suitable or desirable as their next pastor:

You know when the vote comes, I think that it is going to be a reflection of 'we trust our leaders who have brought this person to us'. So by and large the people here largely trust the leadership, and something would have to go very wrong for that person not to be affirmed. There would have to be a pretty significant disconnect. (Urban Board member's response, C2U2BP1, Male, 60's)

As this quotation states, the vote appears to be less about the candidate and the congregation's experience with the person over the course of a Sunday service, or a weekend and more about the level of confidence and trust that the congregation has in the search committee and those leading the church through their time of searching. Governance structures within the sampled churches require that a vote takes place. There is a significant impact of the vote results upon the church, the leadership and the new pastor that may be brought in, particularly when the vote is not a reflection of the qualities and suitability of the candidate, but an indication of confidence in church leadership.

Discussion

This study evaluated the various steps in the hiring process to highlight significant factors, both internal and external to the church, that impact and shape current church hiring practices. Critical issues around pastoral hiring directly related to the church were revealed, like expediency, pragmatism and an emphasis upon success, which are endemic in this evangelical tradition. Individuals could be objectified and manipulated, motivated through psychological strategies in the process, with a strong focus on achievement, which could be seen as a control of individual's emotional hungers. 'Management theory and practice can never be value neutral. Management is underpinned by specific values, whether people are aware of them or not' (Dyck, Starke & Dueck 2009:186). Those values typically reflect societal values and as noted by Dyck et al. emphasise materialism and individualism and have been secularised for decades (p. 186). Those values inform and are demonstrated in the actions that are taken in various practices. Within what may be considered, 'typical' management practices:

There exists a powerful, almost ineluctable force in management to reduce all new ideas and issues into a narrowly defined management paradigm concerned with instrumentality, efficiency, material gain, domination, individual power, resource exploitation, globalization, control, and so on … (Steingard 2005:231)

While not all of these management characteristics were reflected within this study, the core hiring elements and steps evident within the pastoral hiring process reflected a conventional, organisational hiring model. This included: determining selection criteria (education, experience and other qualities) and recruitment methods - whether employment services, web-based job boards or word of mouth; developing a job description and a means for assessing and selecting potential candidates and the method of making a final selection (Olian & Rynes 1984:171). Comments from some participants reflected this paradigm as they identified their need for human resources skills and the ability to interview as two examples of a conventional hiring model. As Steingard (2005) points out though:

Unlike conventional science where the nature of the process is subaltern to results, spiritually informed management theory must consider the process before the outcome. Otherwise, the true nature of the spiritually sourced phenomenon will be overshadowed by results that could have been achieved via traditional, non-spiritual methods. (p. 233)

There appears to be little to distinguish between a typical hiring process and the hiring of a spiritual leader - a pastor. The outcome of either process, if measured solely by simply having a qualified person serving in a role, is the same. Yet, accounts of poor fit and pastoral turnover seem to indicate that something is missing. The reliance upon traditional, non-spiritual methods is now apparently being revealed by the lack of spiritual discernment. This seemed to reveal more of the condition of the church, which may not be limited solely to this singular practice. This study highlighted that outcomes were all important with emphasis placed upon skills, competencies and the perception of anticipated growth and success by a candidate, rather than an emphasis or evaluation of biblical qualifications and character. As Percy (1997) states, 'many of the religious responses to the impacts of culture - individualism, pluralism, consumerism (secularization) are pragmatic … Few are genuinely theological; most are ideological, with theology added for legitimization' (p. 22).

An examination of what other motivators might be influencing the hiring process, or any church practices, might reveal other matters for the church to address and grow in. For example, in the sampled churches there was an element of secrecy and fear as candidates were unwilling to disclose to their current churches that they were applying for other employment in the case that it did not work out. At some point in the process, if two churches are being impacted by a pastoral hiring, then both should be engaged in prayerful consideration and discernment for the sake of the larger body and the unity and witness of the church. This lack of transparency could speak to pragmatic motivations to financially provide over a pastoral ministry being pursued. There is more to consider than the conventional hiring model if the expectation and desire is to have a person within the pastoral role who is more than the product of an organisational process. Even in the development of desired pastoral criteria and role expectations, 'Leadership is reduced to management; faith in providence is replaced with strategic planning; the gifts (charismata) are reduced to advanced skills; spontaneous koinonia is reduced to organised interactions' (Beyers 2015:6). These changes within the hiring practice reflect an uncritical adoption and embracing of management, leadership and administrative philosophies and practices, possibly in pursuit of growth, success, greater efficiencies and meeting the needs and expectations of the congregation rather than the faithful navigation and relevant witness of the church within an ever changing and shifting culture.

There was a glimmer of recognition by participants within this study, of the 'backwardness of the process', the need to somehow 'affirm a sense of calling, not only to ministry but to the particular church' and the 'inability to know a candidate' without taking the necessary time. The need is to set aside the sense of urgency and pragmatism to take the necessary time to know a pastoral candidate and discern a sense of fit and calling. It may be worthwhile for the church to reorient their pastoral search process to address this as a priority. Integrity and character are central to the pastoral role and therefore too, to the hiring process, where a greater emphasis and examination of character and calling is needed within the role expectations, job description and in the consideration of candidates in order to maintain this integrity. This may be addressed through a greater focus on intentional and ongoing discipleship, the development of leaders within the church and an ongoing reliance and trust upon the biblical principles that are to undergird faith and practice.

Implications for churches

This study has implication for leadership development, vocational calling and ministry, the need for reflection on practices and enhancements in the various steps in the hiring process. Firstly, there appears to be a lack in leadership and spiritual development, for ordained leaders and lay members of a church in the selection of their next pastor. What would also serve to help the church in identifying the type of leadership needed within their context; encourage potential, future pastors to respond to a call; build leadership generally within the church to sustain church ministry, community and mission during times of pastoral transition.

Secondly, a discussion should be held within churches about the issue of vocational ministry and calling, whether the call is to any church within their tradition, at any time or whether it is viewed as a specific calling of a pastor to a particular church at a particular time. This would bring greater clarity, accountability and understanding to the ordination process within the denomination and the church. This could enhance the hiring process by requiring more intentionality and inquiry around the elements of the process that reflect the character qualities expected of a pastor, beyond skills and competencies. This could also impact the profiles that are sent from the denominational office as they too have a role in affirming the calling and subsequent ordination of ministers within their denomination. As Fowler (1992) states:

… if in fact what we are doing is granting denominational credentials, i.e., affirming in a formal way that a certain person is gifted for pastoral work and doctrinally suitable for our group of churches, it would seem reasonable to make this action a truly denominational action. This would involve the creation of denominational structures to examine candidates and give an assessment of their suitability, which would, in my opinion, be an improvement over our present system which is somewhat haphazard and not standardized. (p. 35)

Lacking clarity around the concepts of ordination and calling has implications as it contributes to a process that is confusing, challenging and perhaps a contributor to the assumptions that are made within the hiring process and to the regular turnover of pastors that churches may experience. As the sampled churches highlighted, with the great activism in the evangelical churches there can be a lack of awareness of how the underlining values impact church practices. It may be that the church assumes that in any of its practices, simply engaging in prayer sanctifies the process if they achieve their desired outcomes, regardless of how the elements align or represent biblical values. If this tradition holds that biblical criteria is needed for spiritual leadership, then they should be more explicitly expressed and assessed, rather than assumed and overlooked.

Those tasked with engaging in the hiring process should also be adequately trained in the search committee to ensure that they are all aligned with the objectives, candidate criteria, process elements and the mission and vision of the church. Members need capacity building to navigate the hiring process like learning how to incorporate forms of assessment into their pastoral hiring practices, such as personality profiles and assessments, psychometric and behavioural leadership assessments and inventories (Thoman 2009:291) leading to the best fit possible. They should be able to reflect spiritually and practically ask questions throughout the process.

When a church is searching for a pastor, the ministry of the church continues and its practices, particularly when hiring a pastor, would benefit from an ongoing ministry praxis cycle even in the absence of a pastoral leader. A significant resource for a church engaged in a pastoral transition would be to consider hiring an intentional transitional minister to help navigate the transition. A transitional pastor could be invaluable during a church assessment and evaluation process and bring objectivity and additional stability to the congregation and its ministry (Brown 2003; Daehnert 2003; Robinson 2003).

Finally, a critical reflection of the various stages and elements of the pastoral hiring processes regarding the integration of the values, beliefs, theologies and assumptions need to be made and be acted on:

The answer to the secular challenge, therefore, cannot be found in individual self-cultivation alone, but in recovering the traditional power of the church whose basic identity is being shaped as it indwells the Christian story. (Chan 2011:7)

Evangelical churches need to move beyond marketing and recover their distinctive ecclesial and eschatological identity as the church.

Conclusion

This study unpacked pastoral hiring processes and broadly explored the secular impacts of this process on the evangelical denomination. What became apparent throughout this study was the fact that critical consideration and priority of the hiring process and its elements could lead to a more reflective practice using spiritual discernment in practices that ultimately result in the right individual selected for the work.

Acknowledgements

Sections of this manuscript represent a reworking of a doctoral thesis in Practical Theology with the title 'A Practical Theological exploration of Pastoral Hiring processes within the Canadian Evangelical Church', under the supervision of Prof. Dr Marilyn Naidoo, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa, 2022.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationship(s) that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

C.R.B. wrote the article and supervision and editing was executed by M.N.

Ethical considerations

This study received ethical approval from the College of Human Science, University of South Africa (Rec- 240816-052) and all ethical conventions were adhered to during the research.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

References

Beyers, J., 2014, 'The church and the secular: The effect of the post-secular on Christianity', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 70(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v70i1.2605 [ Links ]

Beyers, J., 2015, 'Self secularisation as challenge to the church', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 71(3), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v71i3.3178 [ Links ]

Branson, M.L. & Martinez, J.F., 2011, Churches, cultures and leadership: A practical theology of congregations and ethnicities, Intervarsity Press, Downer's Grove, IL. [ Links ]

British Columbia and Yukon District: The Pentecostal Assemblies of Canada, 2017, BCYD pastoral transition manual, The Pentecostal Assemblies of Canada, Langley. [ Links ]

Brown, R., 2003, 'Interim or intentional interim', Review and Expositor 100(2), 247-254. https://doi.org/10.1177/003463730310000207 [ Links ]

Bruce, S., 2006, 'Secularization and the impotence of individualized religion', The Hedgehog Review 8(1-2), 35-45. [ Links ]

Canadian Baptists of Ontario and Quebec, 2016, CBOQ pastoral and ministry placement manual, Canadian Baptists of Ontario and Quebec, Etobicoke. [ Links ]

Chamberlain, D., 2021, Virginia pastor arrested in prostitution sting appears onstage at church two days later, ChurchLeaders.com, Colorado Springs. [ Links ]

Chan, S., 2011, 'Spiritual practices', in G.R. McDermott (ed.), The Oxford handbook of evangelical theology, pp. 1-17, Oxford University Press, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Christian Reformed Church - Pastor Church Resources, 2021, More than a search committee, 2nd edn., Christian Reformed Church in North America, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Crossley, S., 2016, 'Recent developments in the definition of evangelicalism', Foundations 70(May), 112-133. [ Links ]

Daehnert, W.J., 2003, 'Interim ministry: God's new calling is changing the life of Baptist congregations', Review and Expositor 100(2), 175-190. https://doi.org/10.1177/003463730310000202 [ Links ]

Dreyer, W., 2015, 'The real crisis of the church', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 71(3), 1-5. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v71i3.2822 [ Links ]

Dyck, B., Starke, F.A. & Dueck, C., 2009, 'Management, prophets, and self-fulfilling prophecies', Journal of Management Inquiry 18(3), 184-196. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492608321537 [ Links ]

Fowler, S.K., 1992, 'The meaning of ordination: A modest proposal', Baptist Review of Theology 2(1 Spring), 33-36. [ Links ]

Glenn, N.D. & Hill, L., 1977, 'Rural-urban differences in attitudes and behavior in the United States', American Academy of Political and Social Science 429(1), 36-50. https://doi.org/10.1177/000271627742900105 [ Links ]

Government of Canada, 2003, 2001 Census: Analysis series Religions in Canada, Statistics Canada, Ottawa. [ Links ]

Joynt, S., 2017, 'Exodus of Clergy: The role of leadership in responding to the call', HTS Teologliese/Theological Studies 73(4), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v73i4.4625 [ Links ]

Kwantes, C.T., 2015, 'Organizational culture', in C.L. Cooper, M. Vodosek, D.N. Hartog & J.M. McNett (eds.), Wiley encyclopedia of management: International management, viewed n.d., from https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118785317.weom060152 [ Links ]

Leedy, P.D. & Ormrod, J.E., 2010, Practical research: Planning and design, 9th edn., Pearson Education Inc., Upper Saddle River, NJ. [ Links ]

Lischer, R., 2005, 'The called life: An essay on the pastoral vocation', Interpretation 59(2), 166-175. https://doi.org/10.1177/002096430505900206 [ Links ]

Olian, J.D. & Rynes, S.L., 1984, 'Organizational staffing: Integrating practice with strategy', Industrial Relations 23(2), 170-183. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-232X.1984.tb00895.x [ Links ]

Osmer, R.R., 2008, Practical theology: An introduction, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Paddey, P., 2018, 'Is a clergy crisis coming?', Faith Today Digital 36(6), 44-47. [ Links ]

Percy, M., 1997, 'Consecrated pragmatism', ANVIL 14(1), 18-28. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9418.1997.tb00091.x [ Links ]

Reimer, S. & Wilkinson, M., 2015, A culture of faith: Evangelical congregations in Canada, McGill-Queens University Press, Montreal. [ Links ]

Robinson, Jr., B.L., 2003, 'The future of intentional interim ministry', Review and Expositor 100(2), 233-246. https://doi.org/10.1177/003463730310000206 [ Links ]

Saldana, J., 2016, The coding manual for qualitative researchers, SAGE, London. [ Links ]

Sims, N., 2011, 'Theologically reflective practice: A key tool for contemporary ministry', Reflective Practice: Formation and Supervision in Ministry 31, 166-176. [ Links ]

Slevitch, L., 2011, 'Qualitative and quantitative methodologies compared: Ontological and epistemological perspectives', Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism 12(1), 73-81. https://doi.org/10.1080/1528008X.2011.541810 [ Links ]

Steingard, D.S., 2005, 'Spiritually-informed management theory: Toward profound possibilities for inquiry and transformation', Journal of Management Inquiry 14(3), 227-241. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492605276841 [ Links ]

Stiller, B., 1991, 'A personal Coda', in R.E. VanderVennen (ed.), Church and Canadian culture, pp. 193-202, University Press of America Inc., Lanham, MD. [ Links ]

Swinton, J. & Mowat, H., 2006, Practical theology and qualitative research, 5th edn., SCM Press, London. [ Links ]

The Presbyterian Church in Canada, Toronto 2019, Calling a minister: Guidelines for presbyteries, interim moderators and search committees, The Presbyterian Church in Canada, Toronto. [ Links ]

Thoman, R., 2009, 'Leadership development, part 1: Churches don't have to go it alone', Christian Education Journal 6(2), 282-299. https://doi.org/10.1177/073989130900600207 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Marilyn Naidoo

naidom2@unisa.ac.za

Received: 24 Apr. 2023

Accepted: 01 Sept. 2023

Published: 21 Dec. 2023