Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

HTS Theological Studies

On-line version ISSN 2072-8050

Print version ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.79 n.1 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v79i1.8543

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Theological education and character formation: Perceptions of theological leaders and students

Vhumani Magezi; Walter Madimutsa

Unit for Reformational Theology and the Development of the SA Society, Faculty of Theology, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Character formation is a mandatory requirement for all theological leaders and students. The purpose of this empirical and field research is to understand the perceptions of theological leaders and students regarding the role of theological education in ministerial character formation. The study seeks to discover the difficulty that theological institutions face as they develop and implement moral formation programs. Incongruencies tend to exist between what theological leaders do in the preparation of students for ministry and what they finally produce as 'the product' of their efforts. The study analysed results from interviews with theological leaders and students regarding their perceptions of the role of theological education on character formation. The finding of the study was that college leaders and students showed different perceptions, raising questions on 'what is theological about theological education'. Theological students viewed character formation as key in ministerial formation, whereas theological leaders believed that they played pivotal roles in character formation. Theological students underscored the importance of college leaders as models, the role of churches as essential partners for character formation and the place of co-curricular activities in ministerial formation programs. The study concludes by underscoring key theological implications that are drawn from the study. First, the major contributions that both theological leaders and students make to the ministerial formation process. Second, the need to have ministerial leaders who have skills to minister in diverse contexts. Finally, the need for clarity of purpose of any theological education program.

CONTRIBUTION: This article contributes to the knowledge about the role of theological leaders and contribution of theological students to character formation. The theological leaders and students are leaners and teachers in the ministerial formation process. Sound theological education practice revolves around co-construction of knowledge through the interaction of the students, their college teachers, homes, churches, and the wholesomeness of seminary life and its curriculum

Keywords: Character; character formation; ministerial formation; theological education; theological leaders; theological students.

Introduction

A study by Kretzschmar and Tuckey (2017:1) revealed that theological institutions have difficulty in developing and implementing moral formation programmes, despite embracing the aims for such programmes in their curricula. There is no congruence between what theological institutions do in the preparation of students for ministerial formation and what is conceived as 'the product' of such formation. Some theological institutions end up producing students lacking in personal formation. As a result, the students end up living lives of entitlements and opulence, and even exploiting poor struggling congregations. Some may cling to narrow legalistic understandings of God that excludes compassion and sensitivity towards others (Kretzschmar & Tuckey 2017:1). Therefore, the study examined the perceptions of theological students and theological leaders on the role of theological education in ministerial character formation. What people do in practice is implicit in their perceptions. An examination of their perceptions helped to understand why theological institutions have difficulty in developing and implementing character formation programmes. A literature review was undertaken to situate the research and define key words.

The problem context

Character formation is a mandatory requirement for all theological leaders (Ferdinando 2008:45; Habl 2011:141; Tenelshof 1999:8). Despite theological leaders knowing this mandate, they end up producing students who leave theological institutions lacking in personal character formation (Kretzschmar & Tuckey 2017:1). The problem that this research sought to address was to discover what theological leaders do in the preparation of students for ministry and what they finally produce as 'the product' of their efforts. The study specifically addressed three research questions that ultimately helped to answer these general concerns.

Research questions

The research questions asked were as follows:

-

What are theological students' perceptions of the contributions of theological education in character formation?

-

What are theological college leaders' perceptions of their roles in leadership ministerial formation?

-

What implications can be drawn from these perceptions for the practice of theological education?

Literature review

Understanding key concepts: Theological education, character, and character formation

In order to understand the context of the research questions and the discussion thereon, it is important to define and understand key terms in the research - theological education; character; and character formation.

Understanding the concept of 'theological education'

Hartshorne (1946:235) once highlighted that it is not easy to come up with consensus on what is meant by theological education because the concept means differently to different church organisations. Hartshorne defined theological education as, '… isolated bodies of subject matter which are so taught as to remain largely unrelated to the ministers' tasks' (p. 241). Edgar (2010) maintains that defining the concept involves four components: the content (referring to the subject matter that constitutes it), method (implying processes involved in the practice of theological education), ethos (referring to the spiritual components developed), and context (who is giving the definition), each carrying with it different emphases. Otokola (2017:94) defined theological education as, 'The training of men and women to know and serve God'. Ott (2016:7) noted, 'It is specialised training for pastors and leaders … with its primary and secondary venue as the church and world of science respectively'. Ott (2016:196ff) argued that a comprehensive definition should consider two perspectives: the theological perspective and the theoretical perspective. The former, embraces five elements:

-

theological education as the study of God

-

theological education as the study of the Word of the Bible

-

theological education as a Missio Dei

-

theological education as training people on their powerlessness

-

dependency on the Spirit of God.

Igbari (2001:14-15) saw theological education as an effort at developing three fundamental qualities: knowledge, spiritual growth, and leadership for the church. Easley (2014) posited:

… theological education is the process of enabling the practice of theological and biblical wisdom in leadership events so that contemporary faith communities fulfil their mission to be salt and light to our world and maintain the repository of truth to future generations. (p. 9)

A synthesis of the definitions discussed here, points to the fact that theological education is the practice of preparing men and women for church leadership through a systematic exposure to and study of the Word of God so that believers know how to serve God in His mission. The present researchers view theological education as a coordinated programme of carefully selected disciplines (theory and practice) that is aimed at forming the character of individuals so that they attain attributes and values that capacitate them to know and serve God and others in the church and society as a whole. Such a programme is informed by the church as the location of the theological education task, the content of what is learnt, and the goals of the theological education task.

Understanding the concept of 'character'

Different researchers have come up with different definitions of the concept of character thereby highlighting its complex nature. For example, Nucci (2018:2) defined character as 'the constitution of the self as a whole'. Berkowitz (2012) referred to character as the motivation to act as a moral agent. Midgette (2018:233) defined character as the capacity for self-correcting in response to wrong-doing. Whereas, Holmes (1991:61) posited, 'Character refers to the kind of person one is, the agent who acts rather than just the actions'. Pradhan (2009:3) postulated that character refers to the enduring marks left by life that sets one apart from others, which finds expression in conduct. Perkins and Timmerman (2014) restricted their definition to the issue of values by saying that character is that quality within us that enables us to live by our values. Hauerwas (1975:203) propounded:

Nothing about my being is more me than my character. Character is the basic aspect of our existence. It is the mode of the formation of our 'I'. For it is character that provides the content of the 'I' … It is our character that determines the primary orientation and direction which we embody through our beliefs and actions.

For Hauerwas (2015: 73), character refers to the distinctiveness and individuality of the self, implying that it is not only observable, but also a distinguishable mark of the individual. Grobien (2019:63) shares Hauerwas's conceptualisation and defines character as, 'The mark of integrity, consistency and … incorruptibility … Formed and revealed by action … Shaped by roles and expectations of society'. According to Francisco (2010:77), Christian character is having integrity, loyalty and a servant heart, engraved through significant experiences and decisions. A close look at these definitions points to three main aspects: the drive (or motivation) to act; the moral dimension of that action; and a value system that characterises the actions. The intersection of these three gives rise to engraved marks that characterise an individual as his or her character. Therefore, the present researchers see character as identifying marks that qualify a person's action based on a particular set of moral values. Viewed differently, it is what a person is, in terms of his or her total identifying marks when nobody is watching him or her.

Understanding character formation

Having discussed various perspectives on the concept of character, there is a need to look at the idea of 'character formation' particularly as it relates to the practice of theological education. Character formation is a process (Oxenham 2019) and a journey (Bland 2015:41), implying that it has a starting point and focuses on a goal. According to Pradhan (2009:4), character formation is mainly gradual growth rather than inborn. It grows through activity, effort and taking responsibility through the making of hard choices in life. Character formation is influenced by environmental and social influences. Dykstra (1991) defined character formation as Christian formation which is the activity of God in sanctification, where sanctification is conceived of as the life-long process of formation and transformation. It is argued that the use of the word 'formation' to describe the Christian life has been treated both with suspicion or appreciation on the one hand and controversy or aversion on the other. In the former, formation is part of the jargon referring to the spiritual professionals, and in the latter, it implies violence, restriction, blandness, and objectification (Collicutt 2015:3). What Collicutt (2015:3) implies in the latter is that formation can be an indiscriminate forced action whereby the person being formed has no option but to accept the direction and magnitude of the formational process.

Hauerwas (1975:231) maintained that character formation takes place because we are fundamentally social beings, implying that the character thus formed is relative to the kind of community from which we inherited our primary symbols and practices. Character formation is therefore a legitimate collaborative stance among various community agencies such as the church, the family, peers, and educational institutions, all key to the formational process.

Habl (2011:141) noticed that in the 21st century, questions about character formation are moving from the margins to the centre of social and educational attention because of the decline in the moral fibre across most societies. The world we live in today has transformed into a global village where character is a significant determinant for social harmony and peace. As Habl (2011:141) complained, '… the physical survival of the population is at stake'. These views tend to stress the critical need to address issues of character formation to close the gap of moral deficit in our society. The need to reclaim the forgotten mandate of character formation in our theological education system becomes real as underscored and alluded to by Habl (2011:5).

A brief review of selected studies on character formation

A review of a few studies by Jones (2019:1), Naidoo (2012b), Kretzschmar and Tuckey (2017) and Kagema (2013:1-2) confirm the important regard for ministerial character formation in theological institutions. Jones (2019:1) explored the challenges involved in the formation of ministers within the Baptist tradition in the United Kingdom. The researcher addressed the question: Do we train leaders for quality or quantity? The scholar advocates for the importance of character formation in ministry, insisting that formation should consider earthly challenges such as economic and social issues that affect the process. Jones (2019:42) highlighted the importance of partnerships between colleges and placement churches in the formational process.

In a similar study, Naidoo (2012a:50) underscored the role of theological education for leadership and ministry within the church in South Africa. The scholar investigated how the choice of practitioner or academic educational method impacts the formation of the theological students. The scholar encourages theologians to reconsider the theological education in South Africa, which she argues, is characterised by the context of contradictions at the levels of race, class and gender (Naidoo 2012a:67). She underscores the need for theological institutions, '… to keep an eye on what end product is required, asking what sort of persons the church need'. In a different study Naidoo (2012b:3-4) investigated ministerial formation in a distance learning environment. She explored the theological and pedagogical arguments that challenge ministerial formation within a distance education context. The scholar noticed among others one critical theological argument: the need for formation that requires bodily presence. Regarding the pedagogical argument, the scholar questions whether the use of technology contributes to a deeper student-learning environment necessary for formation.

Kretzschmar and Tuckey (2017:1) did a qualitative study of three students to investigate the teaching and practice of moral formation at the three theological education institutions in South Africa. The findings of the research suggested that teaching and practice that involve relationships are most effective in moral formation. The researchers recommended that teaching institutions should foster students' relationships with God, themselves, with others and the environment. They stressed the importance of relational teaching methods and activities in character formation programmes (Kretzschmar & Tuckey 2017:8).

Kagema (2013:1-2) focused his research on understanding the factors that make the church grow in its relevance to the African needs. The research observed a parallel, direct relationship between church growth on the one hand, and theological education growth on the other. The scholar suggested that growth in the quality of the 'products' of theological education is consequential to and in direct proportion to growth in terms of both the quantity and quality of the church. Kagema (2013:1-2) stressed on paying particular attention to the need to invest in character formation of ministers so as to meet the needs of the church in Africa.

A closer look at the aforementioned reviewed research studies shows the primacy of theological institutions in character formation programmes and for the church as a whole. As perceptions are implicit in what people do in practice, this study of perceptions of theological leaders and students helps us in our understanding of the practice of theological education institutions in as far as character formation is concerned. It is important to understand why theological institutions and their leaders have difficulty developing and implementing students' formational programmes despite acknowledging the aims of such programmes in their curricula. An understanding and appreciation of the perceptions of theological leaders and students will help to understand the nature of the formational processes. The method by which these perceptions are understood and analysed is of critical importance in research. This research used a qualitative approach to understand the perceptions of the two groups: the theological leaders and the students.

The method

The study took note of the nature of the problem under study and the research questions. It used a qualitative approach that involved interviewing students and theological leaders in three purposely selected theological education colleges in Harare. The colleges involved had different theological and confessional backgrounds: evangelical, pentecostal, and reformed. The students were studying either for a BA degree in Theological studies or a Diploma in Theology programme. The theological leaders held administrative or leadership positions at their respective colleges.

The sample consisted of 12 college student leaders and 12 college leaders (the principal, the vice principal, the academic dean, and the student dean) (Table 1). The college leaders were holders of master's degrees in theology or some relevant discipline. Four student leaders were chosen from each of the three theological colleges.

Instruments

A structured interview schedule was used to solicit information from the interviewees. A recorder was used to capture information. The trained assistant researcher recorded and transcribed the interviews.

The interview questions for theological leaders were organised around the following themes:

-

The role of theological education in character formation;

-

The nature and process of character formation.

The interview questions for theological students were organised around one theme: The role of theological education in character formation.

The collected data

The data were obtained from the interviews with theological leaders and students. It was then transcribed, thereby making it possible to identify dominant and emerging themes.

Data presentation

The role of theological education in character formation: Perceptions of theological leaders

The principals' comments

One principal observed:

'… the college's role is to scan and study the environment so that students can serve in different contexts.' (Principal 1, college A, male)

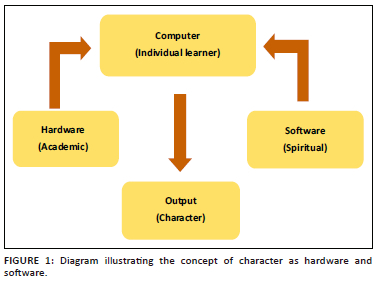

He further illustrated the role of their theological college in character formation by referring to the analogy of a computer device and its two essential components: the hardware and the software (see Figure 1).

The interaction of the hardware and software gives output in the computer, implying that the academic and the spiritual must produce character in the student. The same principal further pointed:

'… there must be a match between orthopraxis and orthodoxy for good character formation.' (Principal 1, college A, male)

Another principal pointed out:

'… that his college's role is to train students with skills that will help them transform the lives of men and women in society. The principal emphasised, character is tested in real life situations … they are called, we will train them, they will change the world - that is transformation.' (Principal 2, college A, male)

The third principal differed considerably from the first and second principals as he stressed:

'Theological education prepares transformational agents with 3 I's - integrity, identity and involvement.' (Principal 3, college C, male)

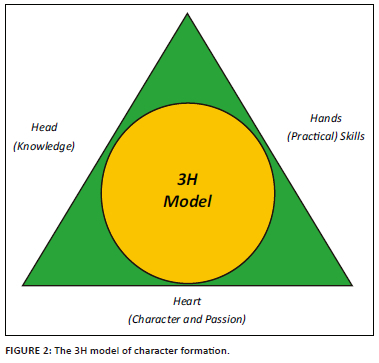

According to the third principal, the basis of that character formation is in the teaching of the three aspects: identity (who am I?); integrity (the real you); and involvement (practice). Therefore, the target for character formation was the head (implying knowledge of theological disciplines and doctrines), the heart (the character and passion), and the hands (involvement - meaning the doing part). According to these insights, students perceived character formation as involving three critical areas: the theory (as it refers to the theoretical academic disciplines); the spiritual dimension (the inner soul or heart); and the practical application (as it refers to how the students applied themselves in practical relationships with others). These three, work together to produce individuals who have integrity, identity, and involvement. According to the students, integrity, identity and involvement define character. The implication is that theological teachers should focus on developing students' integrity (through application and learning of moral values), their interpersonal relationships (by encouraging involvement), and sense of identity.

The vice principals' comments

One vice principal insisted:

'Student formation ensures that students acquire a sound theological foundation which will help them be testimonies in the society.' (Vice principal 1, college C, male)

The other insisted that the role of theological education was to teach society to understand God and develop their relationship with Him. He implied that they insist on academic training at the expense of the practical, saying:

'Most theological colleges in Zimbabwe are bottlenecked.' (Vice principal 2, college C, male)

He maintained:

'True theological education must not only reflect on faith but on practice.' (Vice principal 2, college B, male)

He added:

'Theological education must not aim at training the head, but the heart - the storehouse for character.' (Vice principal 2, college B, male)

Represented diagrammatically (Figure 2), the purpose of theological education is to connect the three: the head (knowledge), the hands (practical skills) and the heart (character).

The third vice principal differed from the other two vice principals. He said:

'Yes we want them to understand God, but mainly to function as entrepreneurs or developmental agents.' (Vice principal 3, college C, male)

Academic deans' comments

The first academic dean expressed the view that their college trains students:

'… to equip the saints for the work of ministry in the church […] and be the salt and light of the world.' (Academic Dean 1, college A, male)

The second academic dean maintained that character formation at her college revolved around the concept of transformational learning. She argued:

'Tell me I hear; show me I see and involve me I learn'. 'Transforming is changing … What transforms a person's character is reading scripture.' (Academic Dean 2, college B, female)

Student deans' comments

The first student dean maintained:

'Theological education is a mover of social change, where praxis and theory go hand in hand.' (Academic Dean 1, college A, male)

The second student dean argued:

'… that theological education is the platform to expound the truth about God, which renews the mind, and a playing field for the interaction of theory and praxis, which gives rise to the formation of character.' (Academic Dean 2, college B, male)

The student dean from yet another college maintained:

'… that theological education develops the learners' skills and character, so that they are able to interpret scripture.' (Academic Dean 3, college B, male)

The nature and process of character formation: Views of theological educators

Within the theme of the nature and process of character formation, different conceptual understandings were noticed.

Principals' comments

One principal defined character as:

'… that which forms as a result of shaping and sieving by both the church and the theological college.' (Principal 1, college A, male)

It is the achievement of the equilibrium of what one believes (software) and the actual practice (the hardware). It is the match between orthopraxis and orthodoxy. He noticed the essential role of academic and extra-curricular components in the process of character formation.

The second principal stressed:

'… spiritual formation is at the centre of character formation. It is the result of tested behaviour response to a situation in real life situation.' (Principal 2, college B, male)

The college adopts a practice known as grasseology where students from diverse backgrounds conflict with their value and belief systems as they interact with others. The third principal's conceptualisation of character formation was that it consisted of three main elements: integrity, identity, and involvement.

Vice principals' comments

The first vice principal affirmed that character formation involves preaching, theological reflection, journal writing and reflection on Scripture. She bemoaned the non-residential status of the college as an impediment to character formation. All vice principals agreed that character formation is a long complex process of emulating the life that Jesus lived.

Academic and student deans' comments

The first academic dean's view of character formation was that it was:

'… the teaching of biblical truths and the intake of truths, … the establishment of convictions … and the transformation of the heart by the Spirit of God … a humble disposition to be taught and accommodate change and the development of a set of values that you live.' (Academic Dean 1, college A, male)

The second academic dean highlighted:

'… that character formation denoted 'fruits of the spirit' in which honesty, integrity, transformation, accountability is categorised as essential qualities.' (Academic Dean 2, college B, male)

The third academic dean referred to character formation as:

'… a planned process of socialising, which influences an individual towards the model - Jesus Christ.' (Academic Dean 3, college C, male)

All student deans held that character formation entailed allowing God to change your behaviour and motivation.

The contribution of theological education in character formation: Perceptions of theological students

Views of theological college A students (Evangelical tradition)

One student from college A viewed character formation as:

'… how one establishes a relationship with God … and how one balances praxis and text.' (Student 1, college A, female)

'The other applauded the college for the group system which helps to facilitate character formation.' (Student 2, college B, female)

The third student reported:

'… that the curriculum fully provides for character formation but warned that colleges should not enrol students who are not cognitively mature as that affects their character formation process.' (Student 3, college C, male)

Views of theological college B students (Pentecostal tradition)

All the respondents at college B applauded the college practice of grasseology. In grasseology students are afforded the following opportunities: sharing tasks collectively; discussing and solving social and relational issues together; mentoring each other; developing affective attitudes; practising what they learn in theory; developing listening and interpersonal skills; and fostering sound interpersonal relationships and friendships.

Views of theological college C students (Reformed tradition)

There was consensus among students from college C that the ecumenical nature of their college was an essential ingredient for character formation. Oe student commented:

'Ecumenism encourages diversity.' (Student 2, college C, female)

The other emphasised:

'… if you have had poor formation, you cannot accept diversity.' (Student 1, college C, male)

The third student highlighted:

'Here at this college we live a life similar to that of komboni [compound] where we share almost everything … who can share these things if you are not character formed?' (Student 3, college C, male)

The fourth student said:

'… there is so much character development that takes place before we come to the college.' (Student 4, college C, male)

What the student was implying was that the home, church and peer members as members of the community play a great deal in character formation.

However, all students at college C confirmed that chapel services, communal college life, ecumenical status of college, attractive academic disciplines, heterogeneous group settings, general cleaning tasks, daily devotions and students' sermons all contribute to character formation.

Discussion and analysis

The role of theological education in character formation

Theological leaders on the role of the theological education in character formation

The data showed that theological educators perceived themselves as indispensable in character formation of the students. They argued that they had a critical role in the delivery of the academic and co-curricular programmes of the college. They perceived themselves as mentors and conduits through which character formation can take place. This perception is important because it places the responsibility of character formation in the previous generation of leaders who were deemed as representing moral figures in society. Exposing students to study the life styles of such revered people in society helps to shape their character. Furthermore, the character of the theological educator is primary as it is the mirror image of that of their students. The emphasis that the participants in this study placed on the character of the theological educator suggests that role modelling of theological educators is important for character formation of students. In similar studies, Sanderse (2013:29-30) underscored the importance of role modelling in character formation. For Kretzschmar and Tuckey (2017:1) and Naidoo (2012b:3-4), it is the relationship between the role model and the students that counts.

Theological students on the role of theological education in character formation

There were very close parallels between the responses of theological educators and theological students. The responses of theological students overwhelmingly triangulated those of theological educators, confirming the notion that theological education has a role to play in character formation. However, there were mixed feelings regarding the commitment of theological colleges in character formation. As the colleges' backgrounds were different, it was possible that the emphasis of each on character formation would be different. It is worth noting that just as theological educators had different understandings of the concept character formation, the same was the case with theological students. The varied understandings by theological educators even from the same college could affect how the students at that college conceived of the concept.

The nature and process of character formation: Views of theological leaders

The concept of character formation was defined differently by theological leaders showing apparent subjective interpretations of the term. In some cases, the concept was understood as spiritual formation. The apparent inconsistencies in defining the concept of character confirmed earlier findings discussed in the study. Nucci (2018:1) confirms that the source of the subjective interpretations of the meaning of character stems from the fact that traditionally the term was defined in terms of virtues, which was problematic. Firstly, it is the lack of agreement across cultures and historical periods as to which qualities count as virtues. Secondly, defining character in terms of virtues contradicts evidence that people apply virtues inconsistently because they behave differently depending on the context. Therefore, this apparent subjective understanding of the concept character formation leads to heterogenous understandings, which affect how each of the colleges implemented their character formation programmes. Worse still is when theological leaders from the same college have different conceptions of character formation. The implication is that each theological leader will adopt a parallel programme of character formation and hence a distorted view of what the college does to form the character of students.

However, the data presented from the responses of theological leaders of the three theological colleges show that there is overwhelming evidence to suggest that their involvement in theological education programmes is pivotal in character development. There was agreement among the college leaders that spiritual formation and ethics, and extra-curriculum programmes were essential determinants for character formation in students. This finding is consistent with findings by Pike et al. (2021:449-466) that differential curriculum intervention produced impact on character development in the development of virtue. We draw the implication that where the curriculum is not nourished with relevant academic disciplines, character formation is stifled. For example, a curriculum that does not have spiritual formation as a key academic discipline may fail to provide opportunities for character formation. Furthermore, it is argued that character formation goes beyond the curricular development and academic disciplines. It ought to be an integration between theory and practice where the latter should be more visible within the public community.

Other co-curricular disciplines cited as important in character development were: sporting activities, chapel services, mentoring groups and also general cleaning activities, confirming earlier findings by Solfemal, Wahid and Pamungkas (2019:923) and Christison (2013:18) that extra-curricular activities give birth to good character and character development. It was noticed that colleges needed to create space for extra-curricular activities at their colleges as Christison (2013:18) pointed out, 'The type of extracurricular activity affects different components of character development', implying the need to have variety in the nature of the activities.

The four academic deans underscored the importance of field work attachments in character formation. This process allows the student the opportunity to put the theory into practice as alluded to by one principal, said:

'… there must be a match between orthopraxis and orthodoxy.' (Principal 1, college A, male)

The other vice principal referred the opportunity to engage in practice as:

'… connecting the head [knowledge], the heart [character] and the hands [skills].' (Vice principle, college B, male)

The second principal highlighted:

'… character is tested in real life situations.' (Principal 2, college B, male)

In terms of the process of character formation, three other themes emerged: theological education in the society; theological education in the church; and theological education in informal settings.

Other themes: Theological education in the society

There was overwhelming consensus that theological education offers an important opportunity for socialisation, which can contribute to character formation. The students coming from various cultural and denominational backgrounds are given the opportunity to character form each other in different group settings. Nucci (2018:6) holds, 'Character does not exist as an entity because it functions coactively within the social context'. Firstly, there was an overwhelming consensus that theological education offers an important opportunity for socialisation, which can contribute to character formation. Secondly, it was observed by theological leaders that theological education is a transformational agent in the society, helping to change the quality of life of the citizenry. However, how that change takes place in a Zimbabwean society where there are many intersecting variables, is difficult to ascertain with specifics. Where a college exists in a residential context, students are presented with enormous opportunities to build character. Nucci (2018:5) holds that contexts that foster responsive and transactional discourse encourage character formation.

Other themes: Theological education in the church

It was overwhelmingly observed by almost all the theological leaders that one of the primary roles of theological education is to produce pastoral leaders for the church. However, it is worth mentioning that not all theological colleges produce pastors for the public church. Some are specific, producing only for their denominational services. Prosperity church contexts are a typical example of such informal settings.

Other themes: Theological education in informal settings

The theological leaders revealed that theological education also takes place in informal contexts outside of a formal theological college. At least within the pentecostal or prosperity churches three models of theological education existed: mentoring process by the man or woman of God (M/WOG); ministry preparation at a prosperity church related theological college; and theological education through conventional established theological colleges. In the first model, the pastor's calling is identified through vetting by the leader of the prosperity church. The candidate is privately mentored and confirmed suitable once he or she is able to perform some ministry tasks.

In the second model, well established prosperity church leaders have established their own theological colleges and appoint their own teachers. Such colleges are usually not full time and do not offer a full theological curriculum but seminars that run during designated times.

In the third model, the prosperity church leaders are those that lie on the middle of the first model and the second model. They demand genuine theological qualifications from trainee pastors who express interest in working with them. Trainee pastors who ascribe to this model are usually given small congregations where their prosperity gospel prowess is tested in the area of deliverances, preaching, and healing.

In all the three models, there are three key ethical implications to note: the ethics of consciousness; the ethics of judgement; and the ethics of behaviour. Firstly, leaders know that they have a duty to protect their congregants from harm that occurs in the process of their church activities. When they fail to comply, they are guilty of the ethic of consciousness. Secondly, church leaders are aware of the ethical dimensions of particular situations or actions, which compel them to make moral judgements. When they fail, they will have flouted the ethic of judgement. Thirdly, sometimes leaders are caught in between their personal beliefs and personal egos and behave in ways that may justify either of the two. When that happens, they may be compromising their ethics of behaviour. These ethical principles are essential guidelines for the good practice of theological education and should not be violated. They are equally important indicators of possible failures in the character formation processes within the informal theological education models discussed.

Summary and conclusion

The purpose of this research was to understand the perceptions of theological education students and leaders on the role of theological education in character formation. This qualitative study used the interview method to solicit answers from the respondents. The data that were collected was coded and two dominant themes emerged: the role of theological education in character formation; and the nature and process of character formation. The data from the two categories of the respondents was presented and triangulated as a test of reliability and consistency. The analysis of data was done in line with the themes that came out in the study. The conclusions from the two sources of respondents (the theological college leaders and the theological students), are that:

-

The theological college leaders perceived themselves as the power source for character formation with significant responsibility to shape the character of students. They perceived the home, school and community as complementing their roles. They viewed themselves as leaners and facilitators of students' character formation through their mentoring programmes. The nature of the academic curriculum and the extra-curricular disciplines they put in place determined the quality of formation. The college leaders believed that their own characters influenced ministerial formation of the students.

-

The nature and process of theological education varies with the theological orientation of the institution. Informal processes of theological education were noted to be common among pentecostal and prosperity churches. These offered different models of theological education and therefore, their emphasis on method and process of character formation varied with the model of theological education offered. The character formation process should be intentional and prioritised in order to produce good results, otherwise theological institutions will continue to produce ministers who are irrelevant to the needs of the church and community in Africa.

-

The theological students perceived themselves as indispensable learners and teachers in the character formation processes. Formal and informal programmes involving group interactions in academic and other menial tasks encouraged formation. In particular, the interactions and relationships between lecturers and their students were found to encourage character formation.

Perceptions are implicit in what people do in practice. Therefore, the conclusions drawn from the study of perceptions of theological leaders and students have profound implications for the practice of theological education. The perceptions highlighted the importance of interactions between home, school, and community in the character formation process. The finding was consistent with Jones's (2019:41) recommendations that partnerships between theological institutions, church and community are essential for 21st century ministry formation programmes. Furthermore, all character formation programmes should focus on improving 'the product' for ministry as alluded to by Naidoo (2012b:50). Finally, the study underscored the value of relationships and relational learning between theological leaders and students, a point which was also stressed by Kretzschmar and Tuckey (2017:8). Therefore, the study encourages theological leaders to develop the church through improving the quality of ministry formation as insisted by Kagema (2013:1-2).

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no financial or personal relationship(s) that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

V.M. and W.M. contributed equally to the writing and conceptualisation of this research article.

Ethical considerations

This article followed all ethical standards for research without direct contact with human or animal subjects.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors and the publisher.

References

Berkowitz, M.W., 2012, 'Moral and character education', in K.R. Harris, S. Graham & T. Urdan (eds.), APA educational psychology handbook Vol. 2: Individual differences, cultural variations and contextual factors in educational psychology, pp. 247-264, American Psychological Association, Washington, DC. [ Links ]

Bland, D., 2015, Proverbs and the formation of character, Wipf & Stock Publishers, Eugene. [ Links ]

Christison, C., 2013, 'The benefits of participating in extra-curricular activities', BU Journal of Graduate Studies in Education 5(2), 17-20. [ Links ]

Collicutt, J., 2015, The psychology of Christian character formation, SCM Press, London. [ Links ]

Dykstra, C., 1991, 'Reconceiving practice', in B.G. Wheeler & E. Farley (eds.), Shifting boundaries: Contextual approaches to the structure of theological education, Westminster/John Knox Press, Louisville, KY. [ Links ]

Easley, R., 2014, 'Theological education and leadership development', Renewal 1(2), 4-26. [ Links ]

Edgar, B., 2010, The theology of theological education, viewed 21 December 2020, from https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/the-theology-of-theological-education-Edgar/a3852ce9a6181f0a07978c54ae004a93e25f7b74. [ Links ]

Ferdinando, K., 2008, 'Theological education and character', African Journal of Evangelical Theology 27(1), 45-64. [ Links ]

Francisco, N.A., 2010, Parenting and partnering with purpose: Linking homes, schools and churches to educate our children, Saint Paul Press, Dallas, TX. [ Links ]

Grobien, G.A., 2019, Christian character formation: Lutheran studies of the law anthropology, worship and virtue, Oxford University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Habl, J., 2011, 'Character formation: A forgotten theme of Comenius's Didactics', Journal of Education and Christian Beliefs 15(2), 141-153. https://doi.org/10.1177/205699711101500205 [ Links ]

Hartshorne, H., 1946, 'What is theological education?', The Journal of Religion 26(4), 235-242. https://doi.org/10.1086/483512 [ Links ]

Hauerwas, S., 1975, Character and the Christian life: A study in theological ethics, Trinity University Press, San Antonio, TX. [ Links ]

Hauerwas, S., 2015, The work of theology, W.B. Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Holmes, A.F., 1991, Shaping character: Moral education in the Christian College, W.B. Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Igbari, O., 2001, A handbook in Theological education in Nigeria: A critical review, Codat Publications, Ibadan. [ Links ]

Jones, S., 2019, 'Ministerial formation as theological education in the context of theological study', Journal of European Baptist Studies 19(1), 41-53. [ Links ]

Kagema, D.N., 2013, 'Theological institutions, the future of the African church: The case of the Anglican Church in Kenya', Research on Humanities and Social Sciences 3(21), 68-81. [ Links ]

Kretzschmar, L. & Tuckey, C.E., 2017, 'The role of relationship in moral formation: An analysis of three tertiary theological education institutions in South Africa', In die Skriflig 51(1), a2214. https://doi.org/10.4102/ids.v51i1.2214 [ Links ]

Midgette, A., 2018, 'Children's strategies for self-correcting their social and moral transgressions and perceived personal shortcomings: Implications for moral agency', Journal of Moral Education 47(2), 231-247. https://doi.org/10.108010.1080/03057240.2017.1396965 [ Links ]

Naidoo, M., 2012a, 'Ministerial formation of theological students through distance education', HTS Teologiese Studies/ Theological Studies 68(2), Art. #1225, 8 pages. https://doi.org./10.4102/hts.v68i2.1225 [ Links ]

Naidoo, M., 2012b, 'Approaches to ministerial formation in theological education in South Africa', Theologia Viatorum 36 (1), 50-75. [ Links ]

Nucci, L., 2018, 'Character: A developmental system', Child Development Perspectives, viewed 21 September 2022, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329001657. [ Links ]

Otokola, E.O., 2017, 'The importance of theological education to the changing world', Continental Journal of Education Research 10(2), 91-111. [ Links ]

Ott, B., 2016, Understanding and developing theological education, Langham Global Library, Carlisle. [ Links ]

Oxenham, M., 2019, Character and virtue in theological education: An academic epistolary novel, Langham Global Library Publishers, Carlisle. [ Links ]

Perkins, D. & Timmerman, J.E., 2014, 'What is character: A critical examination of the debate over virtue ethics and situationism', viewed 02 January 2023, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228654534_A_critical_examination_of_the_debate_over_virtue_ethics_and_situationism. [ Links ]

Pike, M.A., Hart, P., Paul, S., Lickona, T. & Clarke, P., 2021, 'Character development through the curriculum: Teaching and assessing the understanding and practice of virtue', Journal of Curriculum Studies 53(4), 449-466. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2020.1755996 [ Links ]

Pradhan, R.K., 2009, 'Character, personality and professionalism', Social Science International Journal 25(2), 3-23. [ Links ]

Sanderse, W., 2013, 'The meaning of role modelling in moral and character formation', Journal of Moral Education 42(1), 28-42. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2012.690727 [ Links ]

Solfemal, S., Wahid, S. & Pamungkas, A.H., 2019, 'The development of character through extra-curricular programs', Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research 335, 918-926. https://doi.org/10.2991/icesshum-19.2019.143 [ Links ]

Tenelshof, J., 1999, 'Encouraging character formation of future Christian leaders', Journal of Evangelical Theology Society 42(1), 77-90. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Vhumani Magezi

vhumani.magezi@nwu.ac.za

Received: 15 Feb. 2023

Accepted: 30 May 2023

Published: 25 Aug. 2023