Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

HTS Theological Studies

On-line version ISSN 2072-8050

Print version ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.79 n.1 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v79i1.8613

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Understanding riddah in Islamic jurisprudence: Between textual interpretation and human rights

Rokhmadi RokhmadiI; Moh KhasanI; Nasihun AminII; Umul BarorohIII

IDepartment of Islamic Criminal Law, Faculty of Sharia and Law, Universitas Islam Negeri Walisongo, Semarang, Indonesia

IIDepartment of Qur'anic Sciences and Tafsir, Faculty of Theology and Humanities, Universitas Islam Negeri Walisongo, Semarang, Indonesia

IIIDepartment of Islamic Communication and Broadcasting, Faculty of Dakwah and Communication, Universitas Islam Negeri Walisongo, Semarang, Indonesia

ABSTRACT

The application of the death penalty for perpetrators of riddah by fuqaha is a problematic violation of human rights. This is because there is no good reason to show that the punishment for riddah is the death penalty. The existence of the hadith which is considered to be the legitimacy of riddah punishment turns out to be very different from the reality of its application in the history of Islamic criminal law. This article aims to answer academic anxiety about the death penalty for perpetrators of riddah as a result of the ijtihad of fuqaha as well as to confirm the construction of its historical reality in state life. This article finds that some verses of the Qur'an and the hadith which are used as legal basis by fuqaha are only understood textually and treated as absolute theological verses and hadiths, but not based on historical evidence. The history of the application of criminal punishment during the time of the Prophet shows that there is no application of the death penalty to the perpetrators of riddah, except riddah which is followed by criminal acts. So it is not solely because of the act of riddah itself, but because of a greater crime against Islam. The implementation of the death penalty for the perpetrators of riddah which is based on textual interpretation of the hadith, thus has the potential to conflict with the principles of human rights and religious freedom which have been regulated in the Qur'an.

CONTRIBUTION: This study enriches perspectives on the meaning of riddah as one of the strategic issues in Islam and shows that a new interpretation of riddah has become an important idea to promote a peaceful and inclusive society and provide access to justice for all

Keywords: riddah; human rights; Islamic criminal law; death penalty; Islamic jurisprudence; textual interpretation.

Introduction

The imposition of the death penalty for riddah perpetrators has led to a series of 'human rights violations'. The fuqaha in applying riddah punishment only use a textual interpretation so they tend to treat riddah verses and hadiths as an absolute theological verses and hadiths, without considering historical evidences of the application punishment of riddah at the time of the Prophet and the Companions. The various accusations and tendencies against the jurists for their theological thinking illustrate the situation. Qasim Amin (d. 1898), was accused of being an apostate and zindiq, Ali Abd al-Raziq (d. 1966) was convicted of infidel and expelled from his clerical status, Najib Mahfuz (d. 2006) was attempted murder and Nasr Hamid Abu Zaid (d. w. 1995) was decided as an infidel by the Egyptian Court (Kamil 2013).

In general, studies on riddah crime tend to analyse three main focuses. Firstly, the application of the death penalty for perpetrators of riddah based on the hadith of the prophet (Wahyudi 2017). Secondly, the death penalty for perpetrators of riddah in the perspective of Islamic law (Azizah 2015; Firdaus 2020; Syafe'i 2016; Surya 2019); Thirdly, riddah in the context of religious freedom (Dahlan 2010; Mujib & Hamim 2021; Rofikoh 2018). There is no study that comprehensively analyses the potential for human rights violations in the application of the death penalty for riddah perpetrators. A comprehensive understanding of this is really needed to see how the punishment for the perpetrators of riddah should be applied in the perspective of the context of the occurrence of riddah objectively.

This article intends to complement the shortcomings of previous studies, which tend to see human rights violations in the application of punishment for perpetrators of riddah partially. An important underlying argument is that the potential for human rights violations that occur in the application of punishment for riddah perpetrators is not only for the death penalty but also for other punishments. In addition, the intervention of power and the understanding of fuqaha on the text is alleged to have become a new phenomenon of human rights violations against the application of punishment for perpetrators of riddah. The state is placed as an active subject who can apply penalties to criminal acts of riddah and seek legal opinions from fuqaha in accordance with the perpetrators of riddah. Therefore, in particular, this article has two objectives at once, namely analysing the textual interpretation by fuqaha on the text about the death penalty for riddah perpetrators and analysing the implications of textual interpretation on the potential for human rights violations.

Literature review

Riddah in Islam

In the view of Islam, riddah or apostasy is one of the most heinous crimes. These crimes cannot even be compared with the crimes of murder, theft and rape. This is because the essence of this evil is to negate the existence of Allah or to deny the Prophethood of Muhammad (Baker 2018). Terminologically riddah is defined as the return of a person to the origin of his arrival and the return is devoted to the issue of disbelief. This act is based on the will of the perpetrator without any coercion from others (Zailia 2016). In general, riddah can be defined as the conversion of one's religion to another religion or doctrine (Musif 2015), either through speech or deed, thus making a person an infidel or non-religious (Syafe'i 2016).

A person's apostasy according to Islamic criminal law is determined by the presence of two elements. Firstly, leaving the religion of Islam with words and intentions, such as committing shirk or associating partners with Allah and considering ḥarām acts as things that are not ḥarām. Secondly, the apostasy is criminal. The point is that the perpetrator realises that his actions led him out of the religion of Islam (Syafe'i 2016). The existence of a criminal element in apostasy seems to be the basis for Islamic countries to apply punishment to the perpetrators Azizah (2015). Unlike Shafi'i, Abdullah Saeed places apostasy in a different position, namely as a sin and not as a crime. He refers to the provisions of the Qur'an that nearly 150-200 verses in it support freedom of religion and belief. In line with Saeed, Azizah also explained that there is not a single verse of the Qur'an that discusses worldly punishments for riddah. Regarding punishment, this is not only not mentioned in the Qur'an but also the result of ijtihad of fuqaha. Thus, it can be said that the Qur'an as the main source in Islam never mentions that the punishment for apostates is the death penalty (Surya 2019). Therefore, according to Ibn Ashur's maqasidi interpretation, the death penalty for riddah perpetrators needs to be reinterpreted for theological, historical and political reasons. This is because imposing the death penalty for the perpetrators of riddah is contrary to the basic objectives of the religion [maqasid al-syari'ah], namely preserving life and protecting religion (Mujib & Hamim 2021).

Human rights violation

In the Islamic perspective, human rights are determined proportionally in accordance with the position of humans who live and are respected by others (Supriyanto 2014). In this case, human rights are emphasised on simple objectivity, which is a basic human interest based on the elements of a good life (Buchanan 2005). Human rights refer to rights that are naturally obtained from birth in line with human nature itself (Suhaili 2019), as stipulated in the Qur'an that the basic paradigm of human rights is a united nation because of philosophical values (Mukhoyyaroh 2019). Based on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), human rights are rights that are owned by everyone, including the right to life, the right to freedom and security of the body, the right to be recognised for his personality, the right to receive the same recognition as other people according to the law, the right to freely express thoughts and feelings, the right to freedom of religion, the right to social security, the right to education and so on (Assembly 2007).

Regarding human rights violations, the most important thing is how to resolve them. The role of the government and also the community is needed, because basically humans are social creatures (Laurensius Arliman 2017). This means that the enforcement of human rights is the obligation of all levels of society so that justice can truly be realised (Lestari & Arifin 2019). In Indonesia, legal justice in the enforcement of human rights already exists and is regulated, but it is still general in nature, so that its implementation has not been able to cover all human rights issues that always develop with the times (Supriyanto 2014). The concept of human rights, which is represented by the modern standard of living in the field of legal politics, in several ways clashes with the rules of traditional concepts, such as sharia in Islam. However, this does not mean that there is an overall dominance of human rights over religious teachings and traditions (Soeharno 2012).

Death penalty in Islam

Qiṣāṣ in the form of the death penalty is one form of punishment that is legalised by God to Muslims. The death penalty only applies based on very strict considerations, such as the reasons behind the occurrence of a criminal act punishable by the death penalty (Tauhid 2012) and the consistency of the morality aspect as the reason behind it (Rizal 2015). The death penalty can be threatened against four types of acts, namely adultery [muḥṣan], intentional murder, [ḥirabah] and riddah [riddah or apostasy] (Yahya 2013). Therefore, qiṣāṣ in the form of the death penalty in its implementation is given as a last alternative form of punishment for criminal acts (Sari 2020).

The death penalty in Islam has three important goals for the victim, the perpetrator and the community. Firstly, the death penalty aims to achieve equality between crime and punishment (Husni et al. 2012). Like the perpetrators of intentional murder in Islam, the guardian of the slain victim has the right to free amnesty or reimbursement of money [diyat] or to give punishment to the perpetrators of several punishments that make him a better and more careful human being (Husni et al. 2012). Secondly, the death penalty aims to protect the public from similar crimes cases (Dzhuska, Kaminska & Makarukha 2021). The implementation of the death penalty in Islamic societies is expected to prevent future crimes by providing a sense of justice and moral order (Tampubolon & Silalahi 2021). Thirdly, the death penalty purifies people sentenced to death (Pascoe & Miao 2017). This is because the death penalty serves as an atonement for sins to purify the perpetrators of evil (Nugraha 2016). These three objectives make the implementation of the death penalty in Islam more lasting both culturally and structurally (Pritchard 2012).

Research methods and design

This article is qualitative research with descriptive approach. This research aims to reveal how the provisions on riddah are interpreted in authoritative sources and how they implicate potential human rights violations. The research methodology examines and analyses on riddah provisions from the historical and normative perspective. This research was conducted to obtain a comprehensive understanding about riddah, by paying special attention to the legal basis of riddah both from the Qur'an and hadith. The legal basis is then analysed using a historical perspective [asbāb al-nuzūl and asbāb al-wurūd] and its interpretation from classical to modern fuqaha perspectives.

The types of data used in this study include primary and secondary data. Primary data consists of books that discuss Islamic criminal law, such as Al-Tasyrī' al-Jinā'i al-Islāmī by 'Abd al-Qādir 'Audah, which is the main book of Islamic criminal law and is the main reference for anyone who wants to study it. While the secondary data are all books and materials related to Islamic criminal law.

Technically, this research starts from a literature study to get an overview of the object of research. The data are then written and described, starting from the data on the Qur'an and hadiths about riddah in the work of Abdul Qadir 'Audah, to the exposure of secondary data contained in both the fiqh literature and other related literature. This study uses the stages of analysis, which include data-reduction, data-display and data-verification. The analysis method used is content analysis and critical analysis.

Results and discussion

The potential for human rights violations in the context of criminalising riddah exists in three forms: firstly, the death penalty for riddah perpetrators; secondly, restrictions on freedom of belief and thirdly, the intervention of the state and fuqaha in riddah crime.

The death penalty for riddah perpetrators

The hadith that explains the death penalty for riddah states: 'Whoever changes his religion [riddah], then kill him' (Al-Bukhari 1992:372). According to fuqaha, this hadith is also supported by another hadith narrated by Muslim, which states:

The blood of a Muslim is not lawful, except for three things; a married person [muḥṣan] commits adultery; or people who kill so that they are retaliated by being killed; or people who leave their religion [riddah] who are separated from their group" (Muslim 1983:1302-1303).

These two hadiths are used by fuqaha (Abu Hanifah, Malik, Ahmad and Shi'ah Zaidiyyah) as a legal basis that the punishment for perpetrators of riddah is the death penalty (killed), as quoted by 'Abd al-Qadir 'Audah ('Audah 2011, II:591). The death penalty for the perpetrators of riddah according to the majority of fuqaha applies to both men and women. On the contrary, Abu Hanifah said that women and children are not sentenced to death for doing riddah. The punishment for them is to be forced to return to Islam or they will be imprisoned until they repent ('Audah 2011, II: 590-591).

Riddah according to 'Audah is the return or exit of a person (become kufr) after he converted to Islam or cut off his Islamic status in one way, including actions, words, or beliefs ('Audah 2011, II: 580). If so, then to whom was the punishment applied? Fuqaha except al-Shafi'i said that an action called riddah is when someone says something that shows disbelief, so there is no need for kufr intentions. Playful actions and speech can also lead to disbelief. They stipulate the punishment for riddah perpetrators is to be killed (death penalty) ('Audah 2011, II: 591). However, according to al-Shafi'i that the act of riddah is not only measured by actions or words that contain kufr, but the perpetrator must also intend to commit kufr. This is based on the hadith narrated by al-Bukhari which states: 'O people, indeed, that action must be accompanied by an intention and indeed for everyone is what he intended' (Al-Bukhari) (Al-Bukhari 1992:385).

Historically, the hadith that is used as a legal basis to apply the death penalty for perpetrators of riddah by fuqaha according to al-'Asymawi is incorrect. This is because the Prophet Muhammad did not explain what is meant by changing religion [tabdīl al-dīn], whether he changed any religion including converting to Islam to replace his previous religion or whether he meant only changing Islam to another religion. Therefore, in the context of the hadith, what is meant is changing Islam to another religion, so that the death penalty is appropriate for him who has left religion and Islamic law (Al-'Asymawi 1983:128). This opinion is corroborated by Abu Zahrah that the perpetrator of riddah who can be sentenced to death is the perpetrator of riddah who fights against the Muslims regarding their religion. So the meaning of riddah is close to the meaning of committing a crime in the form of a great betrayal [al-khiyānah al-'uẓmā], because when a person leaves his religion, it means that he has joined the enemy's religion, which is the enemy of the Islamic State (M. A. Zahrah 1976:173); (Ali 1990). Likewise, according to Ibn Hajar al-'Asqalani that what is meant by changing religions [riddah] is something outwardly [dzahir]. That is riddah related to defecting to the disbelievers in war, not riddah in [inner] intentions (Al-'Asqalani 2000:336-337). So the application of the death penalty to the perpetrators of riddah is very clear, namely when the perpetrators fight the Muslims with regard to their religion (Syaltut 1966).

Historical evidence shows that the Prophet Muhammad never sentenced to death the perpetrators of riddah, as explained here: Firstly, the narration from Sahih al-Bukhari, in Kitāb al-Aḥkām, chapter bay'ah al-A'rab, explains that the Prophet did not punish a Bedouin who did riddah (Haekal 2018). Secondly, on the Isra' Mi'raj incident that occurred before the Prophet emigrated to Medina. Haekal stated that most of the Meccans who had converted to Islam turned into infidels because the Prophet they believed in as the messenger conveyed his irrational personal spiritual experience. They find it difficult to accept supernatural events that do not make sense (Haekal 2018). Thirdly, at the time of the Fatḥ al-Makkah incident. The Prophet granted forgiveness to all the Quraysh, except for the 17 people who were set to be killed. Those who were killed were because of their great crime against the Muslims. For example, 'Abdullah bin Abi al-Sarh who used to convert to Islam and became one of the writers of revelation, then apostatised and joined the Quraysh by propagating that he had falsified revelation when he wrote it (Haekal 2018). Fourthly, during the time of Abu Bakr al-Siddiq. He did not sentence to death perpetrators of riddah who did not commit insubordination or rebellion (Cooke & Hitti 1952).

Restrictions on freedom of belief

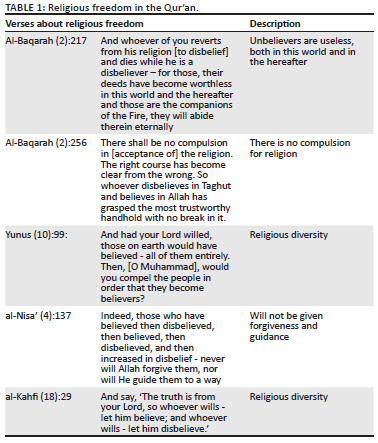

Al-Qur'an emphasises that religion is the freedom of every human being that there should be no coercion by anyone, including by state intervention or fuqaha. This is because choosing a religion must be in accordance with their respective beliefs. Thus, freedom of religion is a human right that should be respected, so it is inappropriate for the state or fuqaha to threaten punishment for the perpetrators of riddah, as long as they do not disturb the security of the state and society. There are three types of sanctions for the perpetrators of riddah: firstly, their good deeds are in vain in this world and in the hereafter; secondly, will not be given forgiveness and guidance and thirdly, not threatened with punishment, including the death penalty. The principle of freedom of religion is as illustrated in several verses of the Qur'an as shown in Table 1.

Explaining surah al-Baqarah (2):256 and Yunus (10):99, al-'Asymawi says about the need for individual freedom in choosing religion according to their respective beliefs and there is no coercion to become a Muslim, because there will be no goodness when someone becomes a Muslim out of necessity. Likewise, if someone comes out of the religion of Islam, it does not make Islam a loser because that person is the one who loses, because he prefers to be a person who does not have a hold of faith [mulḥid] than to be a believer (Al-'Asymawi, 1983:128-129).

The application of the death penalty for riddah perpetrators is a form of limitation on the freedom of one's belief, which is contrary to one of the human rights, namely freedom of religion. Freedom to embrace religion should not only be forced only based on one-sided textual interpretation but must also be considered from the contextual aspect, because the relationship between riddah and human rights is also justified from the normative side of Islam (An-Na'im 1990:109). Thus, it is clear that the Qur'an gives freedom to humans to embrace religion according to their respective choices and beliefs and not to force them to embrace a certain religion, as a form of embodiment of human rights. According to al-Baji (d. 494 H), al-Nakha'i (d. 95 H), Sufyan Tsauri (d. 162 H) and Ibn Taimiyah all perpetrators of riddah must be persuaded to convert to Islam again and not sentenced to death. Even Abdullahi Ahmed An-Na'im denies the death penalty for riddah perpetrators by referring to the QS. al-Nisa (4): 137. Although this act of riddah is condemned, in this verse the perpetrator of riddah is not required to be sentenced to death (An-Na'im 2007:191). It can be concluded that the opinion of fuqaha who have stipulated the death penalty for perpetrators of riddah is incorrect. Riddah that can be sentenced to death is riddah related to defecting to disbelievers who are enemies of Islam, because it is contrary to the general meaning of the verse: 'there is no compulsion in embracing religion' (QS. Al-Baqarah [2]: 256).

In the current perspective, the meaning of riddah has been expanded not only to move from Islam but also to include the meaning of blasphemy. Contemporary fuqaha, such as Abdullah Nashih Ulwan, categorise several behaviours that fall into the category of riddah. For example, the attitude of denying the hadith of the Prophet; characterise Allah with unworthy qualities; believe that Islam is only a religion of worship, an ethical and spiritual religion only, by not believing in Islam as a legal system and a rule of life; believe in and be willing to enforce laws other than God's law and exalting other signs or symbols, such as nationalism and humanism, as goals and propaganda by not believing, to some extent, as God's commands (Kamil 2013). Moreover, the concept of riddah is often used as an excuse to accuse certain parties of having deviated from Islam. For example, accusations of disbelief [takfīr] against Muslim intellectuals in responding to modernity issues, especially human rights issues, because they are considered to have underestimated sharia. It did not stop there, the accusation of riddah against Muslim intellectuals had resulted in an assassination attempt. The trigger is the opinion of Muhammad al-Ghazali, one of the scholars of al-Azhar university, who argues that killing perpetrators of riddah is the duty of a Muslim, when the state is unable to fulfill this task (Kamil 2013). Therefore, the attitude of the majority of fuqaha who categorise riddah as jarimah ḥudūd that can be sentenced to death, as contained in the Hadith narrated by al-Bukhari and Muslim above is something strange. This is because it clearly contradicts the intent of QS. Al-Baqarah (2): 217, which only threatens the void of practice [removing the reward], punishment in the hereafter in the form of eternal life in hell and criticism with harsh words.

State intervention and potential human rights violations in riddah crimes

Egypt is one of the countries that are recorded to still impose the death penalty for riddah. Many Muslim intellectuals have experienced negative treatment in the form of state intervention and fuqaha on personal matters. Among them is Qasim Amin who was accused of apostasy and zindiq (disrupting religion and endangering Muslim society), by traditional Islamic clerics and Egyptian national figures. This treatment was obtained after he published her book entitled 'Taḥrīr al-Mar'ah' [Liberation of Women] in 1898 (Hasri 2018; Siregar 2017). Ali Abd al-Raziq (d. 1966) was convicted of infidelity and expelled from his clergy by King Fuad, the ruler of Egypt at that time. He received this kind of treatment because of a statement in his book 'Al-Islām wa Uṣūl al-Ḥukm', which stated that the caliphate was not a requirement of Islam and that the form of the state was left to the Muslims (Muhammadong 2012; S. Siregar 2018). Najib Mahfuz (1911-2006), author of the novel: "Al-Aulād Haratina" (Children of Gabalawi) in 1962, was assassinated by Egyptian militants because his novel was accused of being heretical and deemed to have insulted God and the Prophets and wanted to replace religion with science and socialism (Nursida 2015). Nasr Hamid Abu Zaid (d. 1995) was branded an apostate and declared it legal for him to be sentenced to death, by the radical Islamist-fundamentalist organisation al-Jihād in Egypt after the publication of the book 'Naqd al-Khiṭāb al-Dīni' [Criticism of Religious Discourse]. The book contains criticisms of Imam Shafi'i and his opinion that religious texts are historical. Nasr also conveyed his critical power towards Imam Shafi'i in the form of a scientific work entitled: al-Imām al-Shāfi'i wa Ta'sīs al-Aidiulujiyyāt al-Wasaṭiyyāt [Imam Shafi'i and the Formation of Moderate Ideology] (Afrizal 2016; Kamil 2013).

In classical Islamic history, the codification of the death penalty for perpetrators of riddah by fuqaha only occurred in the early to mid-Islamic period between the VII and XII centuries AD. At that time, the concept of a state was not clear and orderly. Religion was the foundation for the state, as religion is a symbol of nationalism. Likewise in the Middle East, Islam was a symbol of the state, while in the West, Christianity was also a symbol of the state. A Muslim will become a citizen in a Muslim society, just as a Christian also becomes a citizen or member of a Christian community (Al-'Asymawi 1983:127). The fuqaha relied their codifications on the authority of the Qur'an and the higher authority of the Sunnah and freedom of heart conscience, that may exist, for the criminal consequences of riddah. Therefore, this should be used as a transitional law and can no longer be applied in accordance with the principles of legal evolution in the modern age (An-Na'im 1990:109).

Abdullah Saeed sees the phenomenon of riddah in some Muslim-majority countries that end with criminal punishment as a form of abuse of power and tend to lead to orthodoxy. Saeed assumes that they are more concerned with political aspects and deny the principles of tolerance and religious freedom that are mentioned very clearly in the Qur'an (Saeed 2011). Meanwhile, Hunud Abia Oseni Kadouf and Magaji Umar A. Chiroma considers that the criminal penalty [death penalty] for perpetrators of riddah is not a permanent punishment but rather a political response in order to maintain stability and security of the country because of threats and rebellion from perpetrators of riddah (Kadouf, Oseni & Chiroma 2015). So it can be said that the imposition of punishment is a form of state intervention against perpetrators of riddah. This is in accordance with Al-'Asymawi's assertion that there is no certainty that the Prophet Muhammad has determined the punishment for anyone who left Islam (Al-'Asymawi 1983).

Muhammad Syahrur emphasised that it is important to use modern knowledge systems to understand legal verses or hadiths by using the theory of tsabat an-nash wa harakat al-muhtawa [static text and dynamic content] (Syahrur 2000). This means that the verses and hadith on riddah are unlikely to evolve but realities and problems are always evolving. Therefore, the hadith about riddah must be understood from the problem, the reality and the history of the application of the hadith to the perpetrators of riddah. The hadith should not only be understood in its textual interpretation but also in its contextual interpretation. By relying on modern knowledge systems to understand legal verses or hadiths, Syahrur offers a new legal rule: 'the law will change in accordance with changes in the knowledge system used'. Even Syahrur believes that only by adhering to the principle of tsabat an-nash wa harakat al-muhtawa in understanding legal texts, the crisis of fiqh and law will be solved (Syahrur 2000).

Conclusion

The hadiths that are used as the basis for the death penalty for the perpetrators of riddah by the fuqaha are not well founded or appropriate. This article shows a different thing in that the punishment for the perpetrators of riddah does not have to be death, so that the hadith is only one reason that contributes to legitimising the punishment of riddah.

The application of punishment for perpetrators of riddah is also contrary to the principles of the Qur'an that regulates freedom of religion. Therefore this is a form of violation of human rights, because it is a restriction on the freedom to carry out one's belief. Historical evidences shows that fatwas on death penalty originating from the state (Egypt) are in fact mostly triggered by individuals and collective power political turmoil. Thus, it can be concluded that the perpetrators of riddah can be sentenced to death if they meet several criteria:

-

the perpetrators of riddah fight Muslims with regard to their religion, not just because of riddah;

-

the perpetrators of riddah have committed other criminal acts that could potentially be sentenced to death, for example murder or robbery and

-

the perpetrators of riddah have joined their enemy's religion, then they risk getting a very severe punishment (death penalty), because it is equated with committing a crime of great treason (al-khiyānah al-'uẓmā) to the state.

This article discusses the understanding of riddah in the context of human rights violations, namely restrictions on freedom of religion in a historical perspective. This article also tries to analyse the interpretation of legal arguments to impose the death penalty for riddah perpetrators. The research findings state that the authoritative interpretation of texts by the authorities has triggered interventions that have the potential to violate human rights in the application of punishment for riddah perpetrators. To obtain a more comprehensive understanding, further analysis is needed based on a contextual approach to modern state theories and principles such as justice and universal humanity.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the rector of Universitas Islam Negeri (UIN) Walisongo for supporting this article.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

Authors' contributions

R.R. contributed to conceptualisation, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing of the original draft and supervision of the research. M.K. contributed to conceptualisation, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing the original draft, supervision and research validation. N.A. contributed to the formal analysis, investigation, validation, data curation and research resources. U.B. contributed to the formal analysis, investigation, validation, data curation and research resources. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the writing, review and editing.

Ethical considerations

This article followed all ethical standards for research without direct contact with human or animal subjects.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

References

'Audah, 'Abd al-Qadir, 2011, Al-Tasyri al-Jina'i al-Islami Muqaranan bi Qanun al-Wadl'i, Jilid I & II, Dar al-Kutub al-'Ilmiyyah, Beirut-Libanan. [ Links ]

Afrizal, L.H., 2016, 'Metodologi Tafsir Nasr Hamid Abu Zaid dan Dampaknya terhadap Pemikiran Islam', TSAQAFAH 12(2), 299-324. https://doi.org/10.21111/tsaqafah.v12i2.758 [ Links ]

Al-'Asqalani, I.H., 2000, Fath al-Bari Syarh Shahih al-Bukhari, XII, Dar al-Kutub al-'Ilmiyyah, Beirut-Libanan. [ Links ]

Al-'Asymawi, M.S., 1983, Ushul al-Syari'ah, Dar Iqra', Beirut-Libanan. [ Links ]

Al-Bukhari, I.A., 'Abdillah M. bin I. bin I. bin al-M. bin B., 1992, Shahih al-Bukhari, Juz VII, Dar al-Kutub al-'Ilmiyyah, Beirut-Libanan. [ Links ]

Ali, M.M., 1990, The Religion of Islam, a comprehensive discussion of the sources, Principles and Practices of Islam, The Ahmadiyya Anjuman Isha'at Islam, Michigan. [ Links ]

An-Na'im, A.A., 1990, Toward an Islamic reformation:Civil liberties Human Rights, and International Law, Syracuse University Press, New York, NY. [ Links ]

An-Na'im, A.A., 2007, Islam dan Negara Sekuler: Menegosiasikan Masa Depan Syari'ah, MIzan, Bandung. [ Links ]

Assembly, T.G., 2007, 'Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Chuukese)', Asia-Pacific Journal on Human Rights and the Law 8(1), 101-106. https://doi.org/10.1163/157181507782200222 [ Links ]

Azizah, I., 2015, 'Sanksi Riddah Perspektif Maqasid Al-Shari'ah', al-Daulah: Jurnal Hukum dan Perundangan Islam, 5(2), 588-611. https://doi.org/10.15642/ad.2015.5.2.588-611 [ Links ]

Baker, M., 2018, 'Capital Punishment for Apostasy in Islam', in Arab Law Quarterly, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Buchanan, A., 2005, 'Equality and human rights', Politics, Philosophy & Economics 4(1), 69-90. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470594X05049436 [ Links ]

Cooke, H.V. & Hitti, P.K., 1952, 'History of the Arabs: From the earliest times to the present', The Western Political Quarterly 5(4), 713. https://doi.org/10.2307/442733 [ Links ]

Dahlan, A.R., 2010, 'MURTAD: ANTARA HUKUMAN MATI DAN KEBEBASAN BERAGAMA', ALQALAM 27(2), 311. https://doi.org/10.32678/alqalam.v27i2.599 [ Links ]

Dzhuska, A.V., Kaminska, N.V. & Makarukha, Z.M., 2021, 'Modern concept of understanding the Human Right to Life', Wiadomosci Lekarskie 74(2), 341-350. https://doi.org/10.36740/wlek202102131 [ Links ]

Firdaus, M.A., 2020, 'Hukuman Riddah dalam Perspektif Ijtihad Progresif Abdullah Saeed', KACA (Karunia Cahaya Allah): Jurnal Dialogis Ilmu Ushuluddin 10(1), 25-50. https://doi.org/10.36781/kaca.v10i1.3072 [ Links ]

Haekal, M.H., 2018, Sejarah Hidup Muhammad, e-book, Pustaka Litera Antar Nusa, Bogor. [ Links ]

Hasri, H., 2018, 'Emansipasi Wanita Di Negara Islam (Pemikiran Qasim Amin Di Mesir)', Al-Khwarizmi: Jurnal Pendidikan Matematika dan Ilmu Pengetahuan Alam 2(2), 107-114. https://doi.org/10.24256/jpmipa.v2i2.117 [ Links ]

Husni, A.B.M., Nor, A.H.B.M., El-Seoudi, A.W.M.M., Ibrahim, I.A., Samsudin, M.A., Omar, A.F., et al., 2012, 'Relationship of maqasid ai-shariah with qisas and diyah: Analytical view', Social Sciences (Pakistan) 7(5), 725-730. https://doi.org/10.3923/sscience.2012.725.730 [ Links ]

Kadouf, H.A., Oseni, U.A. & Chiroma, M., 2015, 'Revisiting the role of a Mufti¯ in the criminal justice system in Africa: A critical appraisal of the apostasy case of Mariam Yahia Ibrahim', Pertanika Journal of Social Science and Humanities 23, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.31436/iiumlj.v23i3.227 [ Links ]

Kamil, S., 2013, Pemikiran Politik Islam Tematik: Agama dan Negara, Demokrasi, Civil Society, Syariah dan HAM, Fundamentalisme, dan Antikorupsi, Kencana Prenada Media Group, Jakarta, pp. 86-181. [ Links ]

Laurensius Arliman, S., 2017, 'Pengadilan Hak Asasi Manusia Dari Sudut Pandang Penyelesaian Kasus Dan Kelemahannya', Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2(1), 15-27. [ Links ]

Lestari, L.E. & Arifin, R., 2019, 'Penegakan dan Perlindungan Hak Asasi Manusia di Indonesia dalam Konteks Implementasi Sila Kemanusiaan yang Adil dan Beradab', Jurnal Komunikasi Hukum (JKH) 5(2), 12-25. https://doi.org/10.23887/jkh.v5i2.16497 [ Links ]

Muhammadong, 2012, 'ISLAM DAN NEGARA (Studi Kritis Atas Pemikiran Ali Abdul Raziq)', Publikasi Pendidikan 2(3), 209-215. [ Links ]

Mujib, L.S.B. & Hamim, K., 2021, 'Religious freedom and Riddah through the Maqāṣidī interpretation of Ibn 'Āshūr', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 77(4), a6928. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v77i4.6928 [ Links ]

Mukhoyyaroh, M., 2019, 'Hak Asasi Manusia dalam Kehidupan Sosial Dalam Perspektif Al-Qur'an', Jurnal Online Studi Al-Qur an 15(2), 219-234. https://doi.org/10.21009/jsq.015.2.05 [ Links ]

Musif, A., 2015, 'Pemikiran Islam Kontemporer Abdullah Saeed dan Implementasinya dalam Persoalan Murtad', Ulumuna 19(1), 79-92. https://doi.org/10.20414/ujis.v19i1.1251 [ Links ]

Muslim, A.-I.A. al-H.M. bin al-H. al-Q. an-N., 1983, Sahih Muslim, Juz III, Dār al-Fikr, Beirut-Libanan. [ Links ]

Nugraha, M.T., 2016, 'Verdict off (death penalty) for the drug offender crime in perspective of Islamic education', Ta'dib 20(2), 311-326. https://doi.org/10.19109/td.v20i2.346 [ Links ]

Nursida, I., 2015, 'Isu Gender dan Sastra Feminis dalam Karya Sastra Arab; Kajian Atas Novel Aulad Haratina Karya Najib Mahfudz', Arabic Literature for Academic Zealots 3(1), 1-35. [ Links ]

Pascoe, D. & Miao, M., 2017, 'Victim-perpetrator reconciliation agreements:What can muslim-majority jurisdictions and the PRC learn from each other?', International and Comparative Law Quarterly 66(4), 963-989. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020589317000409 [ Links ]

Pritchard, C., 2012, 'Hidden suicide in the developing world', in Suicide from a global perspective: Psychosocial approaches, Bournemouth University, England. [ Links ]

Rizal, M., 2015, 'Penerapan Hukuman Pidana Mati Perspektif Hukum Islam di Indonesia', NURANI 15(1), 101-116. https://doi.org/10.19109/nurani.v15i2.280 [ Links ]

Rofikoh, N., 2018, 'Kebebasan Beragama di Indonesia perspektif Ratio Legis Hukum Riddah', Al-Jinayah: Jurnal Hukum Pidana Islam 3(2), 454-484. https://doi.org/10.15642/aj.2017.3.2.454-484 [ Links ]

Saeed, A., 2011, 'Ambiguities of Apostasy and the repression of Muslim dissent', Review of Faith and International Affairs 9(2), 31-38. https://doi.org/10.1080/15570274.2011.571421 [ Links ]

Sari, D.N., 2020, 'Implementasi Hukuman Qisas Sebagai Tujuan Hukum Dalam Al-Qur'an', Muslim Heritage: Jurnal Dialog Islam dengan Realitas 7(2), 264-286. https://doi.org/10.21154/muslimheritage.v5i2.2342 [ Links ]

Siregar, E., 2017, 'PEMIKIRAN QASIM AMIN TENTANG EMANSIPASI WANITA', Kafa'ah: Journal of Gender Studies 6(2), 251. https://doi.org/10.15548/jk.v6i2.143 [ Links ]

Siregar, S., 2018, 'Khilafah Islam dalam Perspektif Sejarah Pemikiran Ali Abdul Raziq', JUSPI (Jurnal Sejarah Peradaban Islam) 2(1), 124. https://doi.org/10.30829/j.v2i1.1794 [ Links ]

Soeharno, S.H.M., 2012, 'BENTURAN ANTARA HUKUM PIDANA ISLAM DENGAN HAK-HAK SIPIL DALAM PERSPEKTIF HAK ASASI MANUSIA Oleh', Lex Crimen 1(2), 83-104. [ Links ]

Suhaili, A., 2019, 'Hak Asasi Manusia (HAM) Dalam Penerapan Hukum Islam Di Indonesia', Al-Bayan: Jurnal Ilmu al-Qur'an dan Hadist 2(2), 176-193. https://doi.org/10.35132/albayan.v2i2.77 [ Links ]

Supriyanto, B.H., 2014, 'Penegakan Hukum Mengenai Hak Asasi Manusia (HAM) Menurut Hukum Positif di Indonesia', Al-Azhar Indonesia Seri Pranata Sosial 2(3), 151-168. [ Links ]

Surya, R., 2019, 'Klasifikasi Tindak Pidana Hudud dan Sanksinya dalam Perspektif Hukum Islam', SAMARAH: Jurnal Hukum Keluarga dan Hukum Islam 2(2), 530. https://doi.org/10.22373/sjhk.v2i2.4751 [ Links ]

Syafe'i, Z., 2016, 'KONTEKSTUALISASI HUKUM ISLAM TENTANG KONVERSI AGAMA (RIDDAH) DI INDONESIA', ALQALAM 33(1), 160. https://doi.org/10.32678/alqalam.v33i1.389 [ Links ]

Syahrur, M., 2000, Nahw Ushul Jadidah li al-Fiqh al-Islami, Al-Hali li ath-Thiba'ah wa an-Nasyr li at-Tauzi', Damaskus. [ Links ]

Syaltut, M., 1966, Al-Islam 'Aqidah wa Syari'ah. tanpa kota penerbit, Dar al-Qalam, Beirut, Lebanon. [ Links ]

Tampubolon, M. & Silalahi, F., 2021, 'The way to heaven indoctrination and inefficiency of death penalty as terrorist deterrence', Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues 24(2), 1-11. [ Links ]

Tauhid, A.Z., 2012, 'Hukuman Mati Terhadap Pelaku Tindak Pidana Terorisme Perspektif Fikih Jinayah', IN RIGHT 1(2), 364-368. [ Links ]

Wahyudi, A., 2017, 'Kapasitas Nabi Muhammad dalam Hadits-Hadits Hukuman Mati bagi Pelaku Riddah (Perspektif Mahmûd Syaltût)', AL-IHKAM: Jurnal Hukum & Pranata Sosial 12(1), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.19105/al-lhkam.v12i1.1185 [ Links ]

Yahya, I., 2013, 'EKSEKUSI HUKUMAN MATI Tinjauan Maqāṣid al-Sharī'ah dan Keadilan', Al-Ahkam 23(1), 81-97. https://doi.org/10.21580/ahkam.2013.23.1.74 [ Links ]

Zahrah, M.A., 1976, Al-'Uqubah, Dar al-Fikr al-Arabi, Kairo. [ Links ]

Zailia, S., 2016, 'Murtad Dalam Prespektif Syafi Dan Hanafi', Istinbath 15(1), 67-88. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Rokhmadi Rokhmadi

rokhmadi@walisongo.ac.id

Received: 09 Mar. 2023

Accepted: 26 May 2023

Published: 04 July 2023