Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

HTS Theological Studies

On-line version ISSN 2072-8050

Print version ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.79 n.1 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v79i1.7888

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Romanian Orthodox elementary denominational schools in Transylvania (1868-1921)

Paul BrusanowskiI, II

IFaculty of Orthodox Theology, Lucian Blaga University Sibiu, Sibiu, Romania

IIDepartment of Systematic and Historical Theology, Faculty of Theology and Religion, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

This article presents the development of elementary schools supported by the Orthodox Church in Transylvania between 1868 and 1921. Until 1918, Transylvania belonged to Hungary. In 1918, it was united with the Kingdom of Romania. As Hungary was a particularly complex state in ethnic and confessional terms before 1918, the school system developed under the coordination and financing of the churches. The government intended to gradually replace them with schools run by communities or state. It was not until the end of the 19th century that radical measures were taken. The situation was fully resolved just after the unification of Transylvania with Romania when Romanian Orthodox denominational schools were nationalised and transformed into state schools.

CONTRIBUTION: Although summary works on the history of education in Romania or various research on the history of schools at the local level have appeared in Romanian, the impact of governmental and legislative decisions in Hungary on Orthodox confessional education in Transylvania has not been analysed. In German, the historian Joachim von Puttkamer has dealt with this perspective but especially concerning the schools in the Slovak areas of Greater Hungary. This PhD thesis of the author, P Brusanowski, was the first approach in this direction regarding the Romanians in Transylvania. The article presents for the first time in English a short analysis of the relationship of the Orthodox Church authorities in Transylvania to the educational policy decisions of the central authorities in Budapest. The parallel use of the reports of the Ministry of Education to the Hungarian Parliament, and the reports of the school councils of the executive body of the Romanian Orthodox Church in Transylvania to the ecclesiastical legislative forum, is an important part of this article

Keywords: Romanian Orthodox Church; Transylvania; denominational schools; Eötvös József; Apponyi Albert; Trefort Ágoston.

Introduction

At the beginning of the 20th century, there was a different communion of autocephalous Orthodox Churches (of Byzantine origin) than today. In addition to the four Eastern Patriarchates (Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem) and other older autocephalous churches, like the Church of Cyprus and the Russian Orthodox Church, there were a number of newer national churches (established in the 18th and the 19th centuries), either in South-Eastern Europe (in Greece, Serbia, Romania, Bulgaria and Montenegro) or in Central Europe (Austrian-Hungarian Empire): the Serbian Metropolitanate in Hungary with its seat in Karlowitz (today Sremski Karlovci, Serbia), the Romanian Metropolitanate in Hungary with its seat in Sibiu and the Romanian-Serbian Metropolitanate in the Austrian half of the dualistic monarchy (in Bukovina and Dalmatia with its seat in Czernowitz, today Tscherniwzi, in Ukraine). These churches differed in their relationship to the state on whose territory they existed. In the majority Orthodox states and/or territories (Russia, Serbia, Romania, Bulgaria, Montenegro as well as the province of Bukovina in Austria), the church hierarchy was under the strict control of the state authority. In contrast, the churches in states without an Orthodox majority or character (those of the Ottoman Empire and Hungary) enjoyed autonomy (Milasch 1905:309-312). This autonomy included an own denominational education system. In Hungary, for example, both the Romanian and Serbian Churches, like all other denominations in the country, had their own primary schools, grammar schools and pedagogical academies.

The Orthodox Church of the Romanians in Hungary before 1918

The case of the Hungarian half of the dualistic Austro-Hungarian monarchy is particularly revealing.1 Hungary was one of the European states with the most complex ethnic and confessional composition. On the 282 000 km2 of the territory administered directly by the government in Budapest, there were the following denominations, which in turn had a rather complex ethnic composition. Here is the denominational breakdown in 1880, in Hungary without autonomous Croatia (Csáky 1985:282-283):

-

Roman Catholic: 48.7% of the population (55.14% Hungarians, 19.7% Slovaks, 18.97% Germans).

-

Reformed: 14.4% of the population (98% Hungarian-speaking believers).

-

Orthodox: 13.1% (77.75% Romanians and about 20% Serbians).

-

Greek Catholic: 10.9% (58.84% Romanians, 22.79% Ukrainians, 9.39% Hungarians, 6.83% Slovaks).

-

Lutheran: 7.4% (22.43% Hungarians, 35.01% Germans and 39.57% Slovaks).

-

Jews: 4.9%.

Of these denominations, the Romanian Orthodox Church possessed the highest degree of autonomy vis-à-vis the state (Preda 1914:30). It had its own church constitution (Organic Statute) based on the following three principles (Brusanowski 2011:110-138):

-

Autonomy of the church vis-à-vis the state, that is, the right of the church to govern itself and to enact its own internal statutes.

-

Synodality, which was understood as solidarity between clergy and faithful and manifested itself in a system of separation of powers. Thus, there were separate ecclesiastical legislative and executive bodies. Within the executive bodies at the level of the diocese and the metropolitan province (called consistories), there was also a school council (board).

-

The clear separation of sacramental and canonical matters from administrative, cultural and financial matters, so that all sacramental and canonical problems were administered only by the hierarchs assembled in the Synod of Bishops, administrative matters only by the clergy and cultural (and thus also school) and financial matters by bodies composed of two-thirds lay and one-third clerical.

This church constitution was adopted in 1868, when the Hungarian liberals, who had just taken over the political leadership in Hungary, implemented the first measures of their political programme. The most important liberal 'ideologist' regarding state-ethnic-confessional relations was the Minister of Religion and Education Eötvös József. Within a few months, the Hungarian Parliament passed the following four fundamental laws in 1868: Law Article 9 on the autonomy of the two Orthodox Churches in Hungary, Law Article 38 on the organisation of the elementary school system, Law Article 44 on the 'equal right of nationalities' and Law Article 53 on ensuring full equality and reciprocity between the confessions in Hungary (Csáky 1967:21-27).

The school policy of the Hungarian governments between 1868 and 1895: Communal and confessional schools

Until the middle of the 19th century throughout Central Europe, the denominational school type was a natural reality because teachers and pupils belonged to the same church.

However, the influence of French liberal ideas (in particular the Great School Law of June 1833 issued by François Guizot), as well as economic mobility, led to the emergence in Central Europe of the idea of the mixed school, supported by the communes, in which children of different denominations could learn (Welton 1911:961). In the Austrian half of the Dual Monarchy, the elementary schools were given a distinctly secular character by the laws passed in 1868-1869 (Gernert 1993:439-442). All subjects (apart from religion) were declared free from any influence of a religious community. Schools were to be established and supported by the state, the municipalities or the provinces. But, the Austrian school law was the most liberal law in a German-speaking Catholic state, for it was also accepted in Baden or Bavaria to have both confessional (popularly desired) and state schools (Engelbrecht 1992:113-114). In the most important state of the German Empire (Prussia) J. Wetton (1911) observed:

[I]n connexion with the Kulturkampf, or struggle between the state and the Roman Catholic Church, the School Supervision Law of 1872 reasserted the absolute right of the state alone to the supervision of the schools; but the severity of this law as a measure against Roman Catholic clerical education was considerably modified, as a result of the subsequent reconciliation with the papacy under Leo XIII., and the Prussian system remains […] both for Catholics and Protestants essentially denominational. (p. 965)

In Hungary, the Minister of Religions and Education Eötvös József (1867-1871) chose a middle course. With Law Article No. 38 (Schwicker 1877a:1-41), the educational system in the Hungarian half was designed differently from that in the Austrian half of the Empire. On the one hand, Eötvös provisionally accepted that the schools should continue to be maintained by the denominations. On the other hand, he showed little interest in denominational schools. Instead, he advocated the establishment of communal, denominationally mixed schools. This can be seen even from an analysis of the number of paragraphs given in the law for the different types of schools. For the communal, denominationally mixed schools were given 56 paragraphs in Law Article 38/1868, while only five paragraphs were provided for denominational schools, seven paragraphs for public schools and only one paragraph for state schools funded directly by the ministry. The ministerial instructions of 1869 stipulated that a school committee should be set up in each municipality, comprising all representatives of the denominations in the locality and responsible for supervising the school system in the municipality. Minister Eötvös' hope was to 'unite all the denominational schools in a municipality into one community school and prevent the municipal authorities from maintaining denominational schools in the future' (Berzeviczy 1914:87).

All denominational schools were subject to the supreme state supervision. The state officials were therefore obliged to inspect the denominational schools regularly to check whether the legal provisions were being observed and whether the denominational authorities were fulfilling their duty to provide the schools with adequate facilities. If the state inspectors found irregularities in this regard, they had to notify the heads of the denominations. If the ecclesiastical authorities failed to act even after being notified three times, the government had the right to order the abolition of the denominational character of the school in question, that is, its conversion into a municipal or state school (§ 15). In this case, the faithful of the denomination concerned were obliged to continue paying the school tax, but in the favour of the new municipal school. This school tax could not exceed 5% of the direct taxes to the state.

Minister Eötvös' intention was only partially successful. Within five years, the number of denominational schools increased by 1308, from 234 to 1542. At the same time, 599 new denominational schools were founded, bringing the total number of schools in Hungary to 13 903 (Schwicker 1877b:627).

Eötvös' successor in the ministry, Trefort Ágoston (1872-1888), decided to take new measures to strengthen the municipal and state schools at the expense of the denominational schools. Law Article 28 of 1876 reorganised school supervision and strengthened the state's right of control over denominational schools; at the same time, it obliged the churches to adopt for their denominational schools almost all the rules for the organisation of municipal schools (Schwicker 1877a:68-88).

On the other hand, Trefort was part of the government of Tisza Kálmán, which introduced a new, nationalist policy (Bellér 1990:437-438; Gogolák 1980:1290-1291; Gottas 1974:102). The most appropriate means to achieve this goal was the use of the school and the church. The first visible result of the new policy was the enactment of Law Article 18/1879, according to which the Hungarian language had to be taught in all schools, regardless of their sponsors (Hodoș 1944:181-185). This was to avoid the formation of ethnic parallel societies on the territory of the Hungarian state (Puttkamer 2003:188-191).2 Second, Trefort concluded a kind of pact between the government and the Roman Catholic hierarchy. The government not only secured political support in the House of Magnates (the upper chamber of parliament) but also won the approval of the Catholic bishops for the new nationalist policy. The non-Hungarian Catholic faithful (Slovaks and Germans) lost the support of the church leadership in promoting their national identity. The consequence of this soon became apparent: all Slovak grammar schools were closed, the number of confessional Catholic primary schools with Slovak and German as the language of instruction declined drastically (Puttkamer 2003:139).

Minister Csáky Albin (1888-1894) pursued a new policy in relations with the churches. The Parliament passed the so-called Church Policy Laws, which introduced civil marriage, the acceptance of the 'Israelite religion' and a new law on the 'free exercise of religion' (Gesetzsammlung 1894:479-565; Gesetzsammlung 1895:251-267; László 1989:116-120). Government interference in church affairs increased. The non-Magyar Catholics continued to lose their schools. Moreover, in 1890, Minister Csáky Álbin succeeded in subjecting the Evangelical Lutheran Church from Hungary to government policy (with the notable exception of the Transylvanian Saxon/German Church, which preserved its independence). In this way, even the non-Hungarian Protestants in Hungary were effectively sacrificed by the higher church leadership (Puttkamer 2003:81-83, 140-142). However, the government's national policy was more difficult to apply to the national churches (which included the Romanian Orthodox Church but also the Serbian Orthodox Church and the Lutheran Church of the Transylvanian Saxons). Therefore, the government applied a new strategy by focusing its attention on teachers' salary levels. Law article 26/1893 provided for 300 Gulden per year, plus adequate housing and a garden of 1438 m2. Parishes that could not afford this salary could ask for state support. However, this support was linked to the teacher's loyalty to the Hungarian state. If the church authority refused the material support of the government and did not provide the minimum salary set by law, the local authorities could convert the denominational school into a community school without having to apply the three notices mentioned in § 15 of Act 38/1868 (Gesetzsammlung 1893:573-583).

Reaction of the Romanian Orthodox Church in Transylvania

The Romanian Orthodox Church leadership in Sibiu did not seem to have understood the new education strategy in Hungary and continued to believe firmly in the denominational principle although more and more Western countries were abandoning it. It did not know that it was threatened by competition from community schools. As a result, it did not include elements in the organisation of denominational schools that would have ensured their development (elements that Eötvös had adopted to strengthen the community schools), especially the organisation of 'school committees' and school inspections. No paid school inspectors were appointed, but the 'protopopes' (i.e., archpriests, or in other Christian traditions 'deans') were still considered responsible for the development of the denominational schools, even though their lack of efficiency was obvious. In fact, a reading of the minutes of the diocesan synods reveals a rather high degree of negligence on the part of the local church authorities. There were also endless discussions in these synods and adjournments of decisions. It was not until 1882 that final school regulations were issued (Protocol 1882:82, 189-286). Under these circumstances, the situation of the Orthodox denominational schools not only lagged far behind that of the community schools and the schools of other denominations but in some respects was even regressive.

In 1884, there were 12 692 communities (towns and villages) with 16 205 schools of all categories in the whole of Hungary (Unterrichtswesen 1886:42-45). On the territory of the Romanian Orthodox Archdiocese of Sibiu (in the province of Transylvania), there were 1000 parishes with 822 Orthodox denominational schools (Protocol 1884:161-163). In Hungary, 90.11% of all schools owned buildings (Unterrichtswesen 1886:56), but in Transylvania only 80.54% of Romanian denominational schools, the rest had rented buildings (Protocol 1884:130). In 1896, the number of denominational schools in Transylvania with their own buildings rose to 80.92% (Protocol 1898:93).

Of the 822 denominational schools in 1884, 282 (i.e., 34.3%) did not have classrooms that met legal requirements (Protocol 1884:130). By 1896, the number of denominational schools had fallen to 802, of which only 178 (i.e., 22.2%) did not have adequate rooms (Protocol 1898:93).

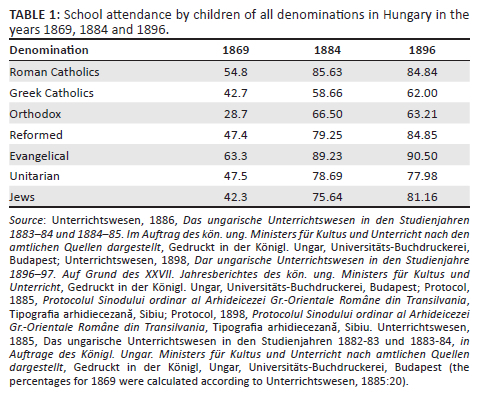

As far as school attendance is concerned, in 1869 it was only 65.53% for 6- to 12-year olds and 6.75% for 12- to 15-year olds in the whole of Hungary (Unterrichtswesen 1886:4). In 1884, school attendance was 85.19% and 63.46%, respectively, and in 1896 85.49% and 66%, respectively (Unterrichtswesen 1898:151). As can be seen, the influence of school legislation (especially the law of 1876) significantly contributed to the increase in school attendance until 1884.

In Transylvania, the school attendance of children attending Orthodox denominational schools was 69.41% and 50.24%, respectively, in 1884 (Protocol 1884:161). In 1896, school attendance fell to 68.50% for the 6-12 age group but rose slightly to 51.67% for the 12-15 age group (Protocol 1898:93).

The development of school attendance by children of all denominations in Hungary can be traced in Table 1 (Brusanowski 2010a:I, 335; Unterrichtswesen 1886:24, 1898:152).

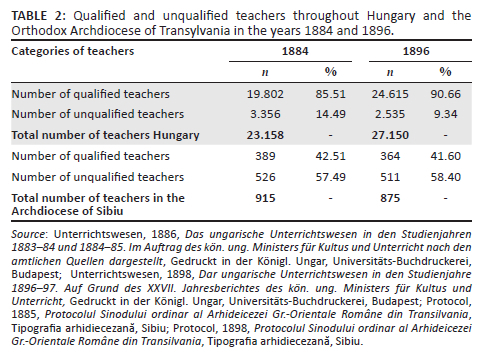

As far as the qualifications of teachers were concerned, the difference was particularly great between the situation in schools throughout Hungary and in Orthodox denominational schools (see Table 2) (Brusanowski 2010a:I, 338; Protocol 1885: 161, 1898:93; Unterrichtswesen 1886:94, 1898:163).

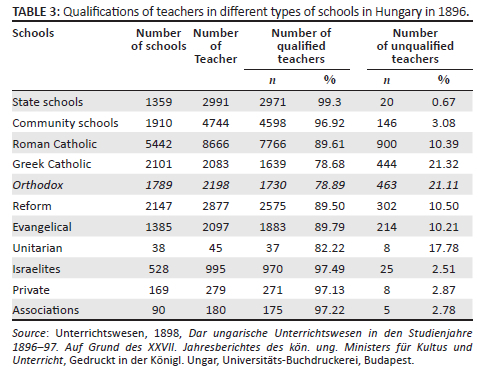

The Ministry of Education had to submit annual reports on the school system to Parliament. This shows that the percentage of qualified teachers in Orthodox schools was 78.89% (see Table 3). Even if one assumed that the vast majority of Orthodox teachers in the two other Romanian Orthodox dioceses (Arad and Caransebeș) as well as in the four Serbian dioceses in Hungary (Timișoara, Vârșeț, Buda, Novi Sad) had a pedagogical diploma, there could not be such a big discrepancy between the data presented by the Orthodox Consistory of Sibiu to the Diocesan Synod of Sibiu and those presented by the Hungarian Ministry to the Parliament in Budapest for the whole of Hungary. The only explanation could be that the Ministry embellished the data for the Orthodox schools, probably to better present the situation of education in Hungary (Brusanowski 2010a:I, 340).

As for teachers' salaries, in 1884 the average salary of the 23 158 teachers in all schools in Hungary was 427 Gulden (Unterrichtswesen 1886:109), while the average salary of teachers in Orthodox denominational schools in Transylvania was only 142 Gulden per year (Protocol 1885:161). Law Article 26/1893 should therefore have had an overwhelming effect on the Romanian denominational school system in Transylvania. However, in his report to Parliament, the Minister noted that the Orthodox denominational schools had been very reluctant to apply for state aid (only for 64 teachers out of a total of 493 applications in the whole of Hungary). This situation was considered in need of clarification, and the Ministry presented its decision to check in the Orthodox schools whether the minimum wage was being respected (Unterrichtswesen 1898:100-101).

And indeed, inspections were regularly carried out in Orthodox schools as well. According to Law 38/1868, they had the right to close denominational schools after notifying the church leadership three times. In most cases, this did not happen. The government was not interested in coming into conflict with the church authorities. And the instruction on the application of Law Article 28/1876 gave the school inspectors the option to tolerate the unsatisfactory denominational schools and ignore them altogether as if they did not exist, which meant that all Orthodox believers who supported the unsatisfactory school through school fees were obliged to pay another fee for the government-approved community school (Ciuhandu 1918:6-9).

The policy of the Hungarian governments between 1895 and 1918: Emphasis on state schools

The year 1896 was celebrated in Hungary as the 'Year of the Millennium' to commemorate the 1000th anniversary of the arrival of Hungarians in Europe in the Pannonian Plain. In this context, the nationalist enthusiasm of society, and thus also of the Hungarian authorities, reached a new peak. The country's ethnic non-Hungarian co-inhabitants became targets, especially their denominational schools or even the community schools in areas with a low percentage of ethnic Hungarians. They were all criticised for not teaching enough Hungarian. Therefore, as early as March 1893, the Education Committee of the Chamber of Deputies demanded that the Ministry prepare a plan to build a dense network of state schools in preparation for the millennium celebration in 1896. Two years later, in January 1895, Minister Wlassics Gyula (1895-1903) stated in his swearing-in speech his intention to expand the network of state schools, but for financial reasons, he rejected the demand of several members of parliament (MPs) to convert all denominational schools into state schools. In February 1897, he presented a concrete programme for the establishment of 1000 state schools in the next five years. By 1903, 728 such schools had been built, employing 1693 teachers (Puttkamer 2003:113-115).

A new impetus for the consolidation of state schools was given by Minister Apponyi Albert with Law Articles 26 and 27 of 1907, which re-regulated the level of salaries for teachers in state, community and denominational schools (with effect from 01 July 1910). Four categories of localities were established, so that the minimum salaries were to be between 1000 and 1200 Kronen (i.e., 500 - 600 old Gulden). If the localities did not provide the teacher with a two-room flat, kitchen and other outbuildings, the teacher was entitled to a rent allowance of between 200 and 600 Kronen (depending on the category of the locality). Of course, teachers at confessional schools had to receive these salaries from the church authorities. If they did not have the necessary funds, they had to resort to the state budget, but only in the case that the schools fulfilled all the facilities laid down in Act 38/1868. If the church authority did not pay the salary required by law and did not draw on state aid for three years, it lost the right to support the school and the school was to be converted into a state school.

Conditions were also set for the teachers at these schools. They had to be free of 'disciplinary offences', the most important of which were: Neglecting the teaching of the Hungarian language, using textbooks that had been discontinued or not approved by the government, following anti-state tendencies. Any act directed against the constitution, the Hungarian national character, the unity, independence and territorial integrity of Hungary was considered an act hostile to the state (§ 20-22). Teachers also had to take an oath of allegiance to the Hungarian state (§ 32).

The salary level set in 1907 was increased by Law 16/1913 on the proposal of Minister Zichy János (Puttkamer 2003:127).

The impact of the Apponyi Act on denominational schools

By May 1908, the Ministry had received some 10 000 applications for additional teachers' salaries and state subsidies for this purpose tripled from 3 350 902 Kronen to 10 745 915 Kronen in just four years (Puttkamer 2003:131-133). Many denominational schools were transformed into state schools. Development of the situation of the various schools in Hungary between 1869 and 1912 can be seen in Table 4 (Brusanowski 2010a:I, 328; Development 1913:122; Unterrichtswesen 1886:32, 39, 1898:157), note the percentage decrease was greatest in the Orthodox schools.

The situation was difficult because the church authorities were faced with the following alternatives: either they sacrificed schools (by not modernising them and not paying the minimum salary for teachers, in which case the school was automatically closed by the state education authority), or they asked for state support to increase teachers' salaries. If they chose the latter, they first had to renovate the schools so that they met the criteria checked by the school inspectors so that they could then apply for state support. Of course, there was also a third alternative, namely, to finance both the modernisation of the school and the salary increase for the teachers from their own funds.

The church authorities were thus faced with a difficult decision. Small schools were sacrificed. Attempts were made to build larger schools in larger village centres. In 1908, a 'culture tax' was introduced for the church schools: Every church official, priest, teacher, pedagogue was to pay 2% of his salary, and the Orthodox 'social elites' were divided into four categories, who were to pay, on a voluntary basis of course, between 10-40 Kronen annually (Protocol 1910:41-51). Finally, in 1910, a consistory school inspector was appointed by competition, namely Onisifor Ghibu (Protocol 1910:40-41). In the same year, he visited the denominational schools and concluded that; 'an unhealthy spirit prevails from top to bottom […] There is much misery, and this is largely not the fault of strangers' (Ghibu 1911:15).

In areas with poorer populations (especially in Hunedoara County, in south-western Transylvania), there was a danger that many schools would be closed without the government having the financial means to establish 'state schools' in their place. Against this background, the county assembly of Hunedoara advised the government as early as 1909 not to apply the law too strictly (Domanyos 1966):

For it is not enough to enforce the law and close unfit schools and remove unqualified teachers, but it is necessary to send teachers with university degrees to the suspended schools […]. Unless urgent action is taken, half the school-age children of the county will not go to school. Therefore, volens-nolens, the old dilapidated and ill-equipped schools must be allowed to continue and the old teachers must continue to teach. (pp. 278-279)

Based on Inspector Ghibu's reports, a balance sheet could be drawn up. In 1907, there were 765 denominational Orthodox schools in Transylvania; in 1912, there were only 664. As some of the schools proved to be insufficient to meet the legal requirements or because there was a lack of qualified teachers, 111 schools were closed (92 in Hunedoara County). Of the remaining 664 schools, 97 were supported exclusively by their own funds, 158 with the help of the diocese and most, 270, with state support. 127 denominational schools lacked the minimum equipment required by the school law, so that they could be closed by the authorities at any time (Protocol CNB 1912:115-116).

Epilogue: The destruction of greater Hungary and the unification of Transylvania with Romania

Apponyi Albert became minister again in 1917-1918. In August 1917, after the entry of the Kingdom of Romania into the First World War and its defeat by the armies of the Central Powers, Minister Apponyi decided to establish a so-called 'cultural zone' in the counties bordering Romania. In this area, the confessional schools were to be nationalised, which was not possible without the consent of the legislative bodies of the Orthodox Church. Contrary to the legislation in force, the government sent 'commissioners' to the diocesan synods to persuade the deputies to accept the nationalisation plan. The deputies of the synods protested and left the session (March 1918). Nevertheless, Apponyi announced that as of June 1918, support for 238 schools in the Archdiocese of Transylvania would be stopped.

After the Aster Revolution at the end of October 1918, the Hungarian opposition seized power in Hungary. On 06 November 1918, the new Minister of Education, Lovászy Márton, sent a telegram to the Orthodox Church authorities announcing that 'the provisions made with regard to the nationalisation of the border schools will be withdrawn and revoked' (Triteanu 1919:61-63, 153-156).

After 01 December 1918, the Romanian National Council of Transylvania took over the power to govern Transylvania and the province was united with Romania.

In the Kingdom of Romania, the Orthodox Church, although considered a 'state Church', was under state control. Church property had been secularised in 1863 and education was completely under state control. The church had no influence on the school system (Brusanowski 2010b:48-68, 80-87).

The new Romanian authorities finally put an end to the existence of the Orthodox denominational schools. Unlike the Hungarian rulers, they showed no mercy to the Orthodox Church authorities. First, they transformed the existing state schools into Romanian 'national schools'. Then they began to ask the teachers to leave the confessional schools and demanded them to be integrated into the state school system. To encourage this, they increased teachers' salaries from October 1920 (Protocol 1921:496).

On the other hand, in August 1921, the school inspectors were authorised to confiscate all the buildings of the denominational schools in which they considered the educational process to be stagnant and to put them at the disposal of the 'state school under construction'. The new 'state school' was put into operation with the transition of the teacher into the state education system (Triteanu 1921:1).

As a result, the Orthodox Church in Transylvania lost all rights to the denominational schools and maintained only ownership of 431 school buildings with 696 classrooms, 274 teachers' flats and about 50 ha of land (Protocol 1924:276; Brusanowski 2007:279-284).

Conclusion

In conclusion, the tradition of denominational schools throughout Hungary was too strong, so that the Hungarian government, unlike the Austrian, did not initially take radical steps to secularise the school system. Article of Law 38/1868, under which the school system in Transylvania was organised until 1925, was based on a false premise. Although denominational schools constituted the majority of schools in Hungary, the law nevertheless contained most of the articles and provisions for communal schools (of the political communes). However, even this solution did not prove satisfactory, and the government changed its educational policy in favour of state schools around 1900.

It was not until after the year 1876 that the state authorities attempted to control the denominational schools more strictly by: (a) requiring the learning of the Hungarian language, and (b) increasing the teachers' salaries so that the churches had to ask for support from the state budget. However, the government was not willing to provide this support without certain conditions related to the adequate equipment of the school buildings and the qualifications of the teachers.

After the unification of Transylvania with Romania, the Orthodox denominational schools were nationalised, despite all the protests of the church leadership.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Author's contribution

P.B. is the sole author of this article.

Ethical considerations

This article followed all ethical standards for research without direct contact with human or animal subjects.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the author.

References

Béla, B., 1990, 'Die ungarische Nationalitäten- Schulpolitik von der Ratio Educationis bis heute', in G. Ferenc (ed.), Ethnicity and society in Hungary, Institute of History of the Hungárián Academy of Sciences, Budapest. [ Links ]

Berzeviczy, V.A., 1914, 'Baron Josef Eötvös als Kulturpolitiker', in Ungarische Rundschau für historische und soziale Wissenschaften, Durcker&Humblot, Jahr. III, München und Leipzig. [ Links ]

Brusanowski, P., 2007, Autonomia şi constituţionalismul în dezbaterile privind unificarea Bisericii Ortodoxe Române (1919-1925), Presa Universitară Clujeană, Cluj-Napoca. [ Links ]

Brusanowski, P., 2010a, Învăţământul confesional ortodox român din Transilvania între anii 1848-1918. Între exigenţele statului centralist şi principiile autonomiei bisericeşti, Presa Universitară Clujeană, Cluj-Napoca. [ Links ]

Brusanowski, P., 2010b, Stat şi Biserică în Vechea Românie între 1821-1925, Presa Universitară Clujeană, Cluj-Napoca. [ Links ]

Brusanowski, P., 2011, 'The principles of the organic statute of the Romanian Orthodox Church of Hungary and Transylvania (1868-1925)', Ostkirchliche Studien 60(1), 110-138. [ Links ]

Ciuhandu, G., 1918, Şcoala noastră poporalăşi darea culturală. Un raport oficios, Tipografia diecezană, Arad. [ Links ]

Csáky, M., 1967, Der Kulturkampf in Ungarn. Die kirchenpolitische Gesetzgebung der Jahre 1894/95, Hermann Böhlaus Nachf, Graz. [ Links ]

Csáky, M., 1985, Die Römisch-Katholische Kirche in Ungarn, in A. Wandruszka & P. Urbanitsch (eds.), Die Habsburgermonarchie. 1848-1918, Bd. IV: Die Konfessionen Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Verlag der Östereichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Wien. [ Links ]

Development, 1913, Entwicklung des Volkunterrichtswesens der Länder der Ungarischen Heiligen Krone, Band 31, Ungarische Statistische Mitteilungen N.S., Budapesta. [ Links ]

Engelbrecht, H., 1992, 'Bemerkungen zur Periodisierung der österreichschen Bildungsgeschichte', in Zur Geschichte des österreichischen Bildungswesen. Probleme und Perspektiven der Forschung, vol. 587, Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Philosophische-Historische Klasse, Sitzungsberichte, Vien. [ Links ]

Gernert, D., 1993, Österreichische Volksschulgesetzgebung. Gesetze für das niedere Bildungswesen 1774-1905, Böhlau, Köln. [ Links ]

Gesetzsammlung, 1893, Gesetzsammlung für das Jahr 1893/ Hrsg. vom kön. ung. Ministerium des Innern, Kommision bei Otto Nagel, Budapest. [ Links ]

Gesetzsammlung, 1894, Gesetzsammlung für das Jahr 1894/ Hrsg. vom kön. ung. Ministerium des Innern, Kommision bei Otto Nagel, Budapest. [ Links ]

Gesetzsammlung, 1895, Gesetzsammlung für das Jahr 1895/ Hrsg. vom kön. ung. Ministerium des Innern, Kommision bei Otto Nagel, Budapest. [ Links ]

Ghibu, G., 1911, Cercetări privitoare la situaţia învăţământului nostru primar şi la educaţia populară, Tipografia arhidiecezană, Sibiu. [ Links ]

Gogolák, V.L., 1974, 'Ungarns Nationalitätengesetze und das Problem des Magyarischen National- und Zentralstaates', in A. Wandruszka & U. Peter (Hsg), Die Habsburgermonarchie 1848-1918, vol. III (Die Völker des Reiches), Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Wien. [ Links ]

Gottas, F., 1974, 'Zur Nationalitätenpolitik in Ungarn unter der Ministerpräsidentschaft Kálmán Tisza', in Südostdeutsches Archiv, XVII/XVIII, 1974/75, pp. 85-107, Kommission für Geschichte und Kultur der Deutschen in Südosteuropa e.V. (KGKDS), Tübingen. [ Links ]

Hodoş, E., 1944, Cercetări cu privire la şcoalelor confesionale ortodoxe române din Ardeal, Tipografia arhidiecezană, Sibiu. [ Links ]

László, R., 1969, 'Die verschiedenen Auffassungen von Natinalitätenpolitik im Ungarn des 19. Jahrhunderts', in Südostdeutsches Archiv, XII, pp. 222-244, Kommission für Geschichte und Kultur der Deutschen in Südosteuropa e.V. (KGKDS), Tübingen. [ Links ]

Milasch, N., 1905, Das Kirchenrecht der Morgenländischen Kirche. Nach den Allgemeinen Kirchenrechtquellen und nach den in den Autokephalen Kirchen geltenden Spezial-Gesetzen, Pacher & Kisic, Mostar. [ Links ]

Preda, D.I.A., 1914, Constituţia bisericei gr.-or. Române din Ungaria şi Transilvania sau Statutul Organic comentat şi cu concluzele şi normele referitoare întregit, Tipografia arhidiecezană, Sibiu. [ Links ]

Protocol, 1882, Protocolul Sinodului ordinar al Arhideicezei Gr.-Orientale Române din Transilvania, Tipografia arhidiecezană, Sibiu. [ Links ]

Protocol, 1884, Protocolul Sinodului ordinar al Arhideicezei Gr.-Orientale Române din Transilvania, Tipografia arhidiecezană, Sibiu. [ Links ]

Protocol, 1885, Protocolul Sinodului ordinar al Arhideicezei Gr.-Orientale Române din Transilvania, Tipografia arhidiecezană, Sibiu. [ Links ]

Protocol, 1898, Protocolul Sinodului ordinar al Arhideicezei Gr.-Orientale Române din Transilvania, Tipografia arhidiecezană, Sibiu. [ Links ]

Protocol CNB, 1912, Protocolul Congresului Naţional-Bisericesc ordinariu al Metropoliei românilor greco-orientali din Ungaria şi Transilvania, Tipografia arhidiecezană, Sibiu. [ Links ]

Protocol, 1921, Protocolul Sinodului ordinar al Arhideicezei Gr.-Orientale Române din Transilvania, Tipografia arhidiecezană, Sibiu. [ Links ]

Protocol, 1924, Protocolul Sinodului ordinar al Arhideicezei Gr.-Orientale Române din Transilvania, Tipografia arhidiecezană, Sibiu. [ Links ]

Puttkamer, J.V., 2003, 'Schulalltag und nationale Integration in Ungarn. Slowaken, Rumänen und Siebenbürger Sachsen in der Auseinandersetzung mit der ungarischen Staatsidee 1867-1918', in Südosteuropäische Arbeiten, vol. 115, De Gruyter Oldenbourg Verlag, München. [ Links ]

Schwicker, J.H., 1877a, Die ungarischen Schulgesetze, sammt den ministeriellen Instruktionen und Cirkular-Schreiben zur Durchführung derselben, Lauffer, Budapest. [ Links ]

Schwicker, J.H., 1877b, Statistik des Königreiches Ungarn, J. G. Cotta'sche Buchhandlung, Stuttgart. [ Links ]

Triteanu, L., 1919, Şcoala noastră 1850-1916, Zona culturală, Tipografia arhidiecezană, Sibiu. [ Links ]

Triteanu, L., 1921, 'Distrugerea şcolilor confesionale', in Telegraful Român. Organ național-bisericesc, vol. LXIX(81), 12-25 November, Sibiu. [ Links ]

Unterrichtswesen, 1885, 'Das ungarische Unterrichtswesen in den Studienjahren 1882-83 und 1883-84', in Auftrage des Königl. Ungar. Ministers für Kultus und Unterricht nach amtlichen Quellen dargestellt, Gedruckt in der Königl, Ungar, Universitäts-Buchdruckerei, Budapest. [ Links ]

Unterrichtswesen, 1886, Das ungarische Unterrichtswesen in den Studienjahren 1883-84 und 1884-85. Im Auftrag des kön. ung. Ministers für Kultus und Unterricht nach den amtlichen Quellen dargestellt, Gedruckt in der Königl, Ungar, Universitäts-Buchdruckerei, Budapest. [ Links ]

Unterrichtswesen, 1898, Dar ungarische Unterrichtswesen in den Studienjahre 1896-97. Auf Grund des XXVII. Jahresberichtes des kön. ung. Ministers für Kultus und Unterricht, Gedruckt in der Königl. Ungar, Universitäts-Buchdruckerei, Budapest. [ Links ]

Welton, J., 1911, 'Education', in Encyclopedia britannica, 11th edn., vol. 8 (online on website 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica/Education - Wikisource, the free online library). [ Links ]

Wickham Steed, H., 1911, 'Austria-Hungary', in Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th edn., vol. 3, viewed n.d., from https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/1911_Encyclop%C3%A6dia_Britannica/Austria-Hungary. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Paul Brusanowski

pbrusan@yahoo.de

Received: 30 June 2022

Accepted: 23 Aug. 2022

Published: 13 Feb. 2023

Project Leader: J. Pillay

Project Number: 04653484

Description: The author is participating as the research associate of Dean Prof. Dr Jerry Pillay, Faculty of Theology and Religion, University of Pretoria.

Note: Special Collection: Orthodox Theology in Dialogue with other Theologies and with Society, sub-edited by Daniel Buda (Lucian Blaga University, Romania) and Jerry Pillay (University of Pretoria).

1 . Hungary was one of the two independent states of the dual monarchy (or Austrian-Hungarian Empire). It had its own statehood, its legislative, executive and judicial bodies independent of Austria and its own citizenship. The unity of the Dual Monarchy was expressed 'in the common head of the state, who bears the title Emperor of Austria and Apostolic King of Hungary, and in the common administration of a series of affairs, which affect both halves of the Dual Monarchy. These are: (1) foreign affairs, including diplomatic and consular representation abroad; (2) the army, including the navy, but excluding the annual voting of recruits, and the special army of each state; (3) finance in so far as it concerns joint expenditure' (Wickham Steed 1911:2).

2 . The number of Slovaks who spoke Hungarian in the counties where they made up the vast majority of the population (in what is now northern Slovakia) was only 3% in 1880. The same was true for the predominantly Romanian-speaking counties in Transylvania. Even in regions where Hungarians made up 40% of the population, only 10% of non-Hungarians knew the state language.