Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

HTS Theological Studies

On-line version ISSN 2072-8050

Print version ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.78 n.4 Pretoria 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v78i4.7526

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Hifz Al-Din (maintaining religion) and Hifz Al-Ummah (developing national integration): Resistance of Muslim youth to non-Muslim leader candidates in election

Muhammad Syukri Albani NasutionI; Syafruddin SyamI; Hasan MatsumI; Putra Apriadi SiregarII; Wulan DayuIII

IFaculty of Syariah and Law, Universitas Islam Negeri Sumatera Utara, Medan, Indonesia

IIDepartment of Public Health, Faculty of Public Health, Universitas Islam Negeri Sumatera Utara, Medan, Indonesia

IIIFaculty of Social Science, Universitas Pembangunan Panca Budi Medan, Medan, Indonesia

ABSTRACT

Resistance towards non-Muslim leaders emerged when the case of blasphemy against Islam was brought against Basuki Tjahya Purnama, known as Ahok, as the governor of DKI Jakarta at that time (DKI Jakarta is mostly inhabited by Muslims). The case of blasphemy committed by Ahok has triggered the resistance of Muslims towards non-Muslim candidates for the regional leader election. This study uses a cross-sectional design conducted by interviewing 1121 Muslim youths who participated in regional head elections in North Sumatra. Multivariate analysis in this study used a logistic regression test with JAPS 16 software. The results of this study indicate that Muslim youth in North Sumatra province have high resistance to non-Muslim candidates for regional heads (governor and mayor). Hifz Al-Din [maintaining religion] (p < 0.001; Exp [β] = 2.505) is seen to affect the resistance of Muslim youth to non-Muslim governor candidates; Hifz Al-Din (p < 0.001; Exp [β] = 2.053) is seen to affect the resistance of Muslim youth to non-Muslim mayoral candidates; Hifz Al-Ummah [developing national integration] (p = 0.001; [β] = 2.194) is seen to have influenced the resistance of Muslim youth to non-Muslim governor candidates; Hifz Al-Ummah (p = 0.011; Exp [β] = 1.800) affects the resistance of Muslim youth to non-Muslim mayoral candidates. Muslim youth have high resistance to non-Muslim leaders when participating in elections. Muslim youth are afraid that prospective non-Muslim leaders will make various policies that will make it difficult for Muslims to carry out various kinds of worship performed by Muslims.

CONTRIBUTION: This study is expected to provide information for non-Muslim leader candidates about the fear of Muslim youth against non-Muslim candidates for the regional leader election, especially regarding the policies to carry out worship for Muslims and to maintain the unity of the Ummah

Keywords: Hifz Al-Din; Hifz Al-Ummah; Muslim youth; non-Muslim leader; resistance.

Introduction

Indonesia has the largest population of Muslims in the world, namely 237.53 million people. The majority of Indonesian residents are represented by the Muslim community. Many scholars think that Indonesia, with its Muslim majority, should be led by a Muslim leader (Ardipandanto 2017; Putra 2019); if Indonesia is not led by a Muslim leader, it will harm Muslims both in religious matters and social life. Moreover, these feelings are exacerbated if non-Muslims are prioritised over Muslims (Suryadinata 2015).

The rejection of non-Muslim leaders by Muslims in Indonesia has very strong reasons. Muslims are disappointed with non-Muslim regional leaders who betray the trust placed in them (Fautanu 2020; Hendrastuti 2019; Syam 2019). Several non-Muslim religious leaders have been proven to issue policies that are contrary to Islamic law, and there are even leaders who comment on one of the verses in the Qur'an about choosing a leader (Djuyandi 2017; Minan 2019; Sholikin 2018).

The Government of DKI Jakarta has issued several policies that are contrary to the customs of Muslims, such as 'forbidding the slaughter of sacrificial animals at schools based on the Governor's Instruction Number 168 of 2015 concerning Pengendalian, Penampungan, dan Pemotongan Hewan' [controlling and slaughtering animals]. In December 2013, the Government of DKI Jakarta issued a regulation on 'Penghapusan aturan pengenaan seragam Muslim di sekolah dasar dan menegah setiap Jumat' [abolishing the rules on the imposition of Muslim uniforms in elementary and primary schools every Friday] based on the circular letter number 48/SE/2014 issued by the Head of the DKI Jakarta Education Office, Lasro Marbun, on 14 July 2014.

Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (known as Ahok), who is a Christian was sentenced for blasphemy against Islam in 2016 because of a speech given whilst he was the governor of DKI Jakarta. In his speech, he said (Atriana 2017):

So don't believe in what people say, maybe in your heart you don't want to choose me as a leader, right? Don't you want to be lied (to be fooled) by Al-Maidah: 51, and so on. That's your right, ladies and gentlemen, so if you think that you can't vote because you are afraid that you will go to hell because you've been fooled like that, that's okay. (n.p.)

This speech was considered blasphemy against Islam by the Indonesian Ulema Council (Indonesian: Majelis Ulama Indonesia [MUI]) and the Muslim community (Muhammadiyah, Front Pembela Islam [FPI] and Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia [HTI]). It had an impact on Ahok, and the slogan 'Asal bukan Ahok' [as long as it is not Ahok] even appeared to characterise Ahok's defeat during the DKI Jakarta Provincial Election; Ahok was imprisoned for blasphemy against Islam. The regional manager of Nahdlatul Ulama (Indonesian: Pengurus Wilayah Nahdlatul Ulama [PWNU]) in DKI Jakarta, K.H. Ahmad Zahari, mentioned that DKI Jakarta residents were free to choose any candidate for the DKI Jakarta general election (Priatmojo 2016).

Various policies issued by the governor of DKI Jakarta (who is non-Muslim) and the incident of blasphemy carried out by a leader in Indonesia have led many Islamic scholars to talk about not choosing non-Muslim leaders because it causes more harm (Bahri 2018; Sham 2019). The Ulema from FPI and HTI are groups that are very strict about the prohibition of choosing non-Muslim leaders for Muslim communities such as the Mayor of Solo, Lurah Lenteng Agung and DKI Jakarta, and if there are Muslims who support their leadership, they are judged to be 'unjust, fasiq [sinful] and hypocritical' (Fathoni 2018; Gammon 2020; Maksum 2017 Mietzner 2018; Suryadinata 2015). Differences in views about choosing non-Muslim leaders have an impact on the fall of the law on non-Muslim leaders, such as in DKI Jakarta where there is a phenomenon of Muslims refusing to pray for the bodies of Ahok supporters (Mahmuddin 2017).

The spread of dogma that encouraged people to choose Muslim leaders was increasingly and massively carried out by scholars in da'wah [Islamic proselytising] in mosques and da'wah carried out in various social media (Majid 2018). This action was also carried out in social media such as Facebook, WhatsApp, Twitter and Instagram (Kharisma 2017). People tended to choose Muslim candidates for regional head elections, and because of issues related to ethnicity and religion, the vision and mission of the candidates for regional head received less attention (Ningsih 2022; Rochayati 2010; Triana 2020). The elections for the regional head that benefited from religious issues tended to divide society and could start conflict (Hasim 2003; Syarif 2021; Sumaya 2020).

Ethnicity and religion contextually have an impact on voting preferences, depending on the region and the sociocultural characteristics of the community. Cornelis-Christiandy, who is a Christian, was elected as a governor of West Kalimantan, which is dominated by the Muslim community (Zakina 2016).

North Sumatra is one of the provinces in Indonesia which has a population of various religions, namely, Muslims, Protestant Christians, Catholic Christians, Confucians, Buddhists, Hindus and others. North Sumatra has an area inhabited by a population of 9 522 822 Muslims (63.3%), 4 011 903 Protestant Christians (26.6%) and 1 102 850 Catholics (7.3%) (Central Agency Statistics [Badan Pusat Statistik] 2018).

North Sumatra province has had non-Muslim governors, namely, Mr Edward Wellington Pahala Tambunan in the period 1978-1983 and Mr Rudolf Pardede in the period 2006-2008. The governors of North Sumatra province did not cause conflicts with Muslims and carried out their leadership roles well until the end of their leadership periods. North Sumatra has 18 regencies with Muslim majorities, 11 regencies with Christian majorities and four regencies with mixed Muslim and Christian populations. Therefore, Muslims in North Sumatra province should not have problems with the leadership of non-Muslim regional head candidates.

Resistance to non-Muslim leader candidates in regional head elections had intensified after the issue of blasphemy committed by the governor of DKI Jakarta. Video clips regarding the blasphemy committed by Ahok were found on various social media, adding to the fear and hatred of Muslims towards Ahok, which had implications for candidates for regional heads of non-Muslim religions in various places. The coverage of blasphemy committed by Ahok circulated on online social media, and the discourse carried out by the Islamic scholars on social media, such as Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp and YouTube, had further increased the resistance of Muslims towards non-Muslim leaders (Riza 2020).

A person will not be a leader in an area unless he is of the same religion as the religious majority in that area. This is not discrimination, but it is done so as not to violate SARA (tribe, religion, race and intergroup) and for the sake of maintaining stability, security and public peace (Hifz Al-Umma). Various Islamic organisations in North Sumatra had triggered society to choose Muslim leader candidates and to reject non-Muslim leader candidates. The Al Washliyah organisation encourages its members to choose Muslim candidates for governor in the hope that the prospective Muslim leaders can uphold Islam in North Sumatra (Lestari 2018). Muslim leaders in North Sumatra will embody the Ulema and Umaro in enforcing amar makruf nahi munkar (inviting or advocating good behaviour and preventing bad behaviour [Purba 2018a]). Kamsinah Ginting, the leader of Organisasi Islam Hidayah in Binjai, revealed that choosing a Muslim candidate for governor is a must for Muslims and a form of struggle for the Islamic religion.

The North Sumatran Muslim Congress (Indonesian: Kongres Umat Islam Sumatera Utara [KUI]) was conducted by the representatives of Islamic organisations and Islamic leaders in North Sumatra. This event was attended by 5000 participants and 37 Islamic organisations. This congress recommended that society choose a Muslim leader candidate in the election of governors and mayors in North Sumatra (Subarkah 2018).

Ustadz Abdul Somad and Ustadz Tengku Zulkarnaen revealed the importance of choosing leaders who care about Muslims and leaders who do not want to spread slander, who want to make North Sumatra dignified ('dignity' is jargon for the regional head candidates). Muslims should not be silent when there are parties that insult and criminalise Islamic scholars. Ustadz Abdul Somad also suggested choosing a leader who cares about North Sumatra, the Prophet Muhammad SAW, and Islam that is rahmatan lil alamin [Islam is a blessing to all nature] (Rangkuti 2018).

For Friday sermons, Ulema in North Sumatra tend to choose the theme of leadership in Islam and the prohibition against choosing infidel leaders. Ulema (Islamic scholars) often explain the dangers of electing infidel leaders in Muslim communities, exemplified by Ahok in DKI Jakarta and the Mayor of Surakarta.

The Islamic teachings on the life of a nation, a state and a society are crucial because a just and prosperous country will be realised if the leaders are judicious so that the people will not suffer. Some principles should be prioritised, namely, (1) al-tawassuth [moderate, middle] or not extreme (liberal-left or fundamentalist-right), not anti-state, believing in theocracy (divinity), aristocracy (kingdom), democracy (populist) and so on. Some aspects required are shura [deliberation], al-'adl [justice], al-musawah [equality] and al-hurriyyah [freedom] by maintaining five human principles (al-ushulul khamsah), namely, guarding the soul (hifz an-nafs), religion (hifz ad-din), property (hifz al-mal), identity of origin or descendants (hifz an-nasl) and self-esteem or honour (hifz al-'irdh ); (2) at-tawazzun, balanced in the application of rules, texts, ratios and reality; (3) al-i'tidal [perpendicular] or not easily provoked; and (4) at-tasamuh [upholding tolerance]. Islam prioritises these benefits in life as well as in politics. The leader is expected to be a figure who can become an example or what is known as uswah hasanah [devout person] who will make Islam a rahmatan lil alamin (Syatibi 1990).

Methods

Study design and administration

This study uses a cross-sectional design to determine the causes of Muslim resistance to non-Muslim leaders in regional head elections. This research was conducted in North Sumatra, Indonesia from January 2021 to December 2021. North Sumatra is one of the provinces that conducted regional head elections in 2018, and the province will conduct another regional head election in 2024. It has a population of various religions, namely, Muslims, Protestant Christians, Catholic Christians, Confucians, Buddhists, Hindus and others.

The researchers created announcements for prospective respondents to participate in this study through several social media such as Instagram, Facebook and WhatsApp groups. Then the prospective respondents who were willing to participate and met the study criteria were contacted via WhatsApp. The researcher distributed a questionnaire link through Google Forms, an online questionnaire containing the questions for this study.

Participants

To be eligible for the study, participants had to meet the following criteria: between 17 and 25 years of age, Muslim and currently living in North Sumatra, Indonesia. In addition, the participants should have participated in regional head elections, whether regent or mayoral elections or governor elections. The participants were also willing to vote in the regional head election, whether for regent or mayor or governor. The study was followed by 1121 Muslim youth who were willing to be respondents and to complete all stages of the research.

Measure

Hifz Al-Din [maintaining religion]. The question for Hifz Al-Din is that non-Muslim regional heads are afraid to make various policies that could damage the teachings of Islam and obedience to Allah, such as causing difficulties in praying, legalising usury, legalising liquor or alcohol, allowing the proliferation of more deviant sects and so on (Syatibi 1990).

Hifz Al-Umma [developing national integration]. The question for Hifz Al-Ummah is that non-Muslim regional heads are afraid to make various policies that could damage the people or nationality, such as government policies that do not support Muslims in carrying out various activities such as going to madrasa (Islamic schools) (Syatibi 1990). The cases of corruption, collusion and nepotism would be increasingly rampant. The cases of people who use psychotropic narcotics would be increased, the ukhuwah Islamiyah in Indonesia would be tenuous and Muslims would feel insecure in carrying out various activities (Syatibi 1990).

Regarding Muslim youth resistance against non-Muslim regional leadership candidates, the question relates to the desire of Muslim youth to elect candidates for regional heads such as non-Muslim governors and mayors, if they are nominated in their area in the regional head elections in 2024.

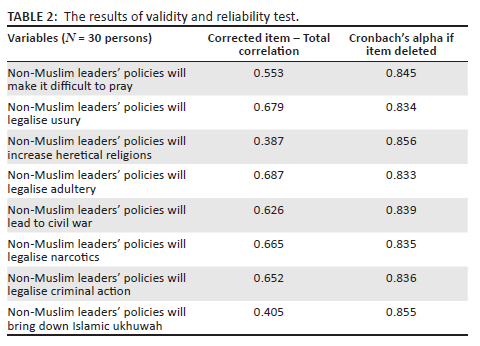

The researchers carried out the validity and reliability test of 30 Muslim youths regarding Hifz Al-Din, Hifz Al-Ummah and the resistance against the non-Muslim regional leadership candidates. The researchers conducted a validity test with the corrected item-total correlation value with the r table value of 0.361. The reliability of the data follows the Cronbach's alpha method to measure the instrument from one measurement, provided that if r count > r table or a significant value of 0.8, then it is declared reliable (Murti 2011).

Data analysis

This study will also display cross-tabulation data between Hifz Al-Din and Hifz Al-Ummah on resistance of Muslim youth to non-Muslim leadership candidates in the election. The analysis in this study will follow multiple logistic regression analyses. Researchers will also display Exp (β) to evaluate the influence of Hifz Al-Din and Hifz Al-Umm ah on resistance of Muslim youth to non-Muslim leadership candidates in the election. Firstly, the researchers calculated the mean and standard deviation (SD) of the variables. Secondly, they performed statistical hypothesis testing analyses, in all cases adopting a two-tailed p < 0.05 as the significance threshold with chi-squared and multiple regression analysis using IBM SPSS 20.

Results

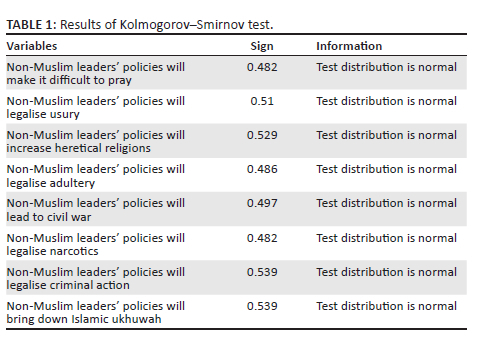

This study analyses the causes of resistance of Muslim youth to non-Muslim leadership candidates in the general election. Before carrying out the analysis test, the researchers conducted a normality test using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The results of the study are presented in Table 1.

The results of this study indicate that the results of the normality test using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test show that it has a p value of > 0.05, which means a normal distribution.

The results of the validity and reliability test (Table 2) conducted on 30 Muslim youths in North Sumatra revealed that the validity test using the corrected item-total correlation had a value of r = 0.553, meaning that participants believe non-Muslim leaders' policies will make it difficult to pray; r = 0.679, non-Muslim leaders' policies will legalise usury; r = 0.387, non-Muslim leaders' policies will increase heretical religious practices; r = 0.687, non-Muslim leaders' policies would legalise adultery; r = 0.626, non-Muslim leaders' policies will lead to civil war; r = 0.665, non-Muslim leaders' policies will legalise narcotics; r = 0.652, non-Muslim leaders' policies will legalise criminal action; and r = 0.405, non-Muslim leaders' policies will bring down Islamic ukhuwah with a value of r count > 0.361, which means the question item is valid.

The reliability test using Cronbach's alpha has a value of r = 0.845, that is, participants believe non-Muslim leaders' policies will make it difficult to pray; r = 0.834, non-Muslim leaders' policies will legalise usury; r = 0.856, non-Muslim leaders' policies will increase heretical religious practices; r = 0.833, non-Muslim leaders' policies would legalise adultery; r = 0.839, non-Muslim leaders' policies will lead to civil war; r = 0.835, non-Muslim leaders' policies will legalise narcotics; r = 0.836, non-Muslim leaders' policies will legalise criminal action; r = 0.855, non-Muslim leaders' policies will bring down Islamic ukhuwah with the value of r count > 0.8, which means the question item is reliable.

The results of the logistic regression analysis in this study indicate that the variable 'non-Muslim leaders' policies will make it difficult to pray' affects the resistance of Muslim youth to non-Muslim governor candidates (p < 0.001; Exp [β] 2.505) and non-Muslim mayors (p < 0.001; Exp [β] 2.053). The variable 'Non-Muslim leaders' policies will lead to civil war' affects the resistance of Muslim youth against non-Muslim candidates for governor (p = 0.001; Exp [β] 2.194) and non-Muslim candidates for mayor (p=0.011; Exp [β] 1.800) (Table 3).

Muslim youth with the view of 'non-Muslim leaders' policies will make it difficult to pray' can be seen to have 2.505 times as much resistance to non-Muslim governor candidates. Muslim youths who consider that 'non-Muslim leaders' policies will make it difficult to pray' have 2.053 times as much resistance to non-Muslim mayoral candidates (Table 3).

Muslim youth who have the view that 'non-Muslim leaders' policies will lead to civil war' have 2.194 times as much resistance to non-Muslim governor candidates. Muslim youth who have the views that 'non-Muslim leaders' policies will lead to civil war' have 1.800 times as much resistance to non-Muslim mayoral candidates (Table 3).

Discussion

The case of blasphemy against Al-Maidah: 51 carried out by Ahok as a governor of DKI Jakarta became a turning point for strengthening Muslim resistance to non-Muslim leaders (Nurhajati 2020). The blasphemy committed by Ahok is not only a socioreligious phenomenon, but this action is also very monumental and historical, especially for Muslims in Indonesia (Abdullah 2017; Huda 2019). The pros and cons of Ahok's statement became a controversy, but on 11 October 2016 a fatwa was issued by the Indonesian Ulema Council (Indonesian: MUI) that the statement made by Ahok was blasphemy of religion. This was used by Ahok's political opponents to describe Ahok as a non-Muslim governor who damaged Islam. However, there were still some scholars from the Nahdlatul Ulama and Muhammadiyah, for example, Buya Syafi'i Maarif, who mentioned that Ahok's action was not considered blasphemy.

Ahok is also considered a governor who often humiliates people in public, so he is not in accordance with the existing norms (Marshall 2018; Mietzner 2018). The Government of DKI Jakarta has issued several policies that are contrary to the habits of Muslims in carrying out worship in Islam, such as 'forbidding the slaughter of sacrificial animals in schools based on the Governor's Instruction Number 168 of 2015 concerning Pengendalian, Penampungan, dan Pemotongan He wan' [controlling and slaughtering animals].

The fatwa issued by the Indonesian Ulema Council (Indonesian: MUI) regarding Ahok's blasphemy became the basis for Islamic scholars from FPI and HTI to fight against Ahok politically by suggesting that the public not vote for infidel (non-Muslim) leaders on social media and in mosques. The success of Ulema FPI and HTI in the Jakarta regional election indicates a political succession in Indonesia is likely to be adopted by a number of other political successions in its various regions (Mukti 2019). Religious ideological factors are the driving force for religious communities to take part in regional head elections (Assyaukanie 2019).

Muslims believe that religion must be protected and that protection of Islam entails protecting the teachings of Islam so that Muslims do not convert to other religions (Nurlaelawati 2016). The leader's policy to maintain religion is one of the wishes of the community, especially for people who have lived for a long time in the area.

The Regent of Cianjur Regency is a devout Muslim and applies the values of Islamic teachings in people's lives (Lukito 2016). Cianjur Regency has very adaptive and accommodating regulations related to sharia regulations, such as the use of headscarves for women; this is inseparable from the regional head who accommodates various sharia regulations through various regional policies (Lukito 2016).

The policies of regional heads are related to religious issues and the application of sharia law in their area (Fenton 2016; Maksum 2017). People in Indonesia claim that religion is an important element in their lives, including their political behaviour (Azra 2018). People in Papua tend to want a leader who fits the dominant society, namely, a Christian one, because they want a leader who supports the mission of making a Bible city (Mu'ti 2019). Similarly, the residents of Bali want a leader who could propose various rules in support of Hinduism (Hamid 2020).

A good leader is one who can unite the people and fight for the teachings of the Islamic religion in various Islamic policies (Lukito 2021). Leaders must be firm in addressing various existing problems related to Islamic belief and religion so that there will be no problems, such as the Ahmadiyah problem in Cianjur Regency (Lukito 2016).

Front Pembela Islam (Islamic Defenders' Front) revealed that Ahok was a non-Muslim leader who disturbed Muslims in Jakarta. The policies issued were anti-Islam and caused chaos amongst Muslims (Abdullah 2017; Hidayatullah 2021). Ahok was believed to hate Islam, belittle the ulema and insult Muslims. Muslims were strongly advised not to vote for Ahok as the governor of DKI Jakarta (Hasyim 2019; Hidayatullah 2021).

If the government is not careful in making policies related to beliefs and religions, it will increase the risk of conflict based on religion, especially in areas that have multiple ethnicities and religions (Elyta 2021; Ngusmanto 2016). Security will make people respect racial, ethnic, religious and political differences (Kristianus 2016; Kurtz 2008). Differences in political choices also create internal conflicts within Islamic organisations and have even caused the head of an Islamic organisation to resign from his position (Rasyidin 2016).

The National Movement to Guard the Fatwa of the Indonesian Ulema Council (Indonesian: Gerakan National Pengawal Fatwa [GNPF] MUI) formed the ijtima ulama [agreement of the meeting of scholars] as an effort to support a candidate who has a vision and mission in accordance with the views of GNPF MUI. The National Movement to Guard the Fatwa of the Indonesian Ulema Council is considered to be a representation of Muslims in choosing a pair of prospective leaders in the hope that the prospective leaders will not betray Muslims if they are elected (Assyaukanie 2019). Leader policies can lead to conflict and social integration. Unfair debate and competition-based religion will result in contravention and prejudice in an atmosphere of social jealousy and will increase the risk of social conflict (Ningsih 2022).

The religious elite shows a firm attitude towards corruption, invites people to fight injustice and urges the government to continue to roll out democratic processes and openness; therefore, it can be said that they are carrying out high politics. Political morality lies in the amar ma'ruf nahi mungkar movement, meaning that the government has carried out noble politics (Pababbari 2009).

Religion is used by various parties as a means of winning elections, and one team of pairs of candidates for regional heads creates religious conflicts between communities. For example, if a certain religion is the head of the region, it will cause chaos or war. Religion actually always teaches noble things and is a moral guide even in running every existing government (Ikhwan 2018; Triana 2020).

For the Muslim community of North Sumatra, politics cannot be separated from strong and basic Islamic values, such as the concepts of faith, Islam and ihsan [filial piety to Allah SWT], justice, da'wah and also rahmatan lil alamin. Islamic values as rahmatan lil alamin are what shape perspectives, attitudes and behaviours, including factors that shape people's identity politics (Tanthowi 2019). Whether as a leader, or being led, individually or in a community, the role and function of religion as an instrument of strengthening ethnicity and nationality in a democratic life will be realised again. The role and function of religion at this level also proves the grounding of the meaning and mission of Islam as rahmatan lil alamin (Muhamad 2017).

Islamic organisation became one of the most important components in Muslim candidates winning the elections for governors in North Sumatra. The leader of the Islamic organisation from PB - Alwashliyah, Yusnar Yusuf Rangkuti, revealed that a Muslim candidate could embody the leadership of the Prophet in North Sumatra and would make North Sumatra safer for Muslims (Purba 2018a). Muhammadiyah, another Islamic organisation in North Sumatra, also participated in supporting the Muslim candidates for the governor election in North Sumatra. Muhammadiyah did not conduct a direct campaign, but directed the election of Muslim leader candidates through Islamic lectures conducted in the smaller sections of Muhammadiyah (Simarmata 2018).

Ustadz Abdul Somad is known as an Islamic scholar whose lectures are easily understood by people of different circles. He has humorous interludes in his lectures and is known for his mastery of religious teachings, for which he has become a role model in Indonesia. Tengku Zulkarnain is the Deputy Secretary-General of the central MUI (English: Indonesian Ulema Council), one of the pioneers of the 212 Islamic Defence and the one who criticised Jokowi-Jusuf Kala's regime based on a religious perspective. In addition, photos of governor candidates with Habib Razieq in Makkah during the Umrah and videos showing Islamic scholars inviting society to choose Muslim leader candidates were circulated in the community to influence people to choose Muslim leader candidates.

Ulema in North Sumatra also supported the Muslim candidates for governor election during the Friday sermons and the Islamic lectures. The Ulema tended to raise the theme of leadership in Islam and the prohibition of choosing infidels as leaders, especially before the election of regional heads. The choice of the theme during the Friday sermon and the Islamic lectures was inseparable from the North Sumatran Muslim Congress event (Indonesian: KUI) which was attended by Islamic leaders and Islamic organisations.

The results of this study indicate that those Muslim youths who have the view of 'non-Muslim leaders' policies will make it difficult to pray' have a 2.505 times resistance to non-Muslim governor candidates. Muslim youths who consider that 'non-Muslim leaders' policies will make it difficult to pray' have a 2.053 times resistance to non-Muslim mayoral candidates.

Muslims in North Sumatra, besides being presented with a narrative of choosing a Muslim leader to protect the religion of Islam, also received a narrative of choosing a Muslim leader to keep the Ulema from being persecuted. Many people in North Sumatra understand the issue that if a non-Muslim leader is elected during the election of the governor and deputy governor of North Sumatra province, the Ulema (who are loved by Muslims) will be persecuted by the tyrannical government. The election of the governor of North Sumatra is one of the ways of today's jihad that must be followed by Muslim communities in North Sumatra to elect the pair of Muslim leaders. Islamic narratives and symbols continue to be displayed in front of the public by religious leaders and governor candidates when visiting various places during the campaign, with the promise that they will prioritise Muslims in various policies if elected and will make Islam victorious, and Muslims will not experience chaos or commotion.

Ustadz Abdul Somad (UAS) answered questions asked in his lecture regarding Muslims choosing infidel leaders; UAS firmly answered by giving the analogy, 'goat meat cooked with potatoes (halal-halal), dog meat cooked with potatoes (haram-halal)'. 'Between goat curry with potatoes and dog curry with potatoes, which one will you choose?' he asked. The people attending his lecture answered 'goat', then he continued his explanation by saying that 'the potatoes cannot make the dog to be halal. What I mean is that in some districts there are Muslim candidates paired with non-Muslim candidates, and this mean the potato curry with?'The participants replied 'dog', and the atmosphere of the study was filled with laughter. The statement of not choosing non-Muslim as leaders was not only mentioned during Islamic lectures, but also was seen on banners that influence people to elect a faithful leader and to prohibit the election of non-Muslim leaders. This was widely circulated on 24 June 2018, especially at Jl. Protokol in Medan and in the al-Jihad Mosque at Jl. Abdullah Lubis, 160. The Election Supervisory Body (Indonesian: Badan Pengawas Pemilu [BAWASLU]), as the supervisor in the contestation of democracy, could not do anything formally because the scattered banners were the prerogative of Muslims to practise their religious teachings. It was written in the banner that (Susetio 2018):

Did you know? The prohibition of choosing a non-believer as a leader is found more than the prohibition on adultery, eating pork, and drinking alcohol, if this kind of prohibition is found lesser but obeyed, then why previous prohibition is ignored? (n.p.)

Muslims in North Sumatra should view maqashid sharia in a dharuriyat [basic needs] manner, it will have implications for the perspective of the Muslim community (and the general public at large) to be able to see the legal reality not only in law as an object, but also law as a subject and law as a living value in society. The context in the state is how the practice of Islamic law in Muslim communities will strengthen their Islamic spirit without affecting their human attitude towards people of different religions. When political choices and plurality are not addressed properly and wisely, it will lead to conflicts between religions and within one religion, which will then increase the risk of social disintegration (Zainuddin 2015). Religious leaders are not allowed to impose beliefs and ideologies on others that are contrary to their own religion and beliefs.

The religion of Muslims must be strictly guarded against all forms of threats. The threat could come from outside or from within the Muslim community itself. The outside threat refers to non-Muslims, whilst the internal circle refers to the heretics. The consequences of guarding religion (Hifz Al-Din) are to legalise the death penalty for non-Muslims who mislead Muslims and to punish heretics who aggressively invite people to follow them (Al-Ghazali 2006).

The construction of Hifz Al-Din according to al-Syatibi is carried out in two aspects: firstly, min janib al-wujud, which means preserving religion by carrying out aspects that strengthen religion, such as performing religious rituals, faith, vowing the two sentences of creed, prayer, zakat, fasting, pilgrimage and other rites; secondly, min janib al-'adam, namely preventing elements that are destructive to religion, such as jihad, killing people who convert to another religion (apostates) and prohibiting heretical practices (Syatibi 1990).

The Islamic Community Congress (Indonesian: KUI) was held in Medan from late March 2018 to early April 2018 and was attended by a number of figures such as Amien Rais, Yusril Ihza Mahendra and Gatot Nurmantyo. The results of the KUI were summarised in the North Sumatran Islamic Ummah Charter (Indonesian: Piagam Umat Islam Sumatera Utara). One of the points of the charter calls for electing leaders - governors, regents, mayors and deputies - based on the criteria of the Qur'an and Sunnah, namely, the Muslim-Muslim candidates to uphold the teachings of Islam and reduce the criminalisation of Islamic scholars (Simamora 2019).

The results of this study indicate that Muslim youths who perceive non-Muslim leaders' policies will lead to civil war will have a 2.194-time risk of experiencing resistance to non-Muslim governor candidates. Muslim youth who consider non-Muslim leaders' policies will lead to civil war will have a 1.800 times risk of experiencing resistance to non-Muslim mayoral candidates.

The study of futurologists (the ability to see or to manage life in the future), therefore, from a positive side, has concerns about choosing a non-Muslim leader because it is contrary to the welfare principle and can be seen positively if it does not give subjective discrimination to non-Muslim candidates, causing stratification, discrimination and unequal treatment of people of different religions. Secondly, it can be viewed negatively if the fear of choosing a non-Muslim leader actually raises subjectivism (close your eyes to see the truth and reality), then to see Hifdz ummah, which is more relevant to the context of state and state development, to maintain the interests of the people (Hifdz ummah) the community does not make religion the only truth value to choose a leader. The way of religion and religious attitude can be a symbol and a record to assess whether a prospective leader is capable of being trustworthy in their responsibilities and carrying out the vision and mission of development. If fear of choosing non-Muslims is a way to eliminate objectivity in seeing the vision and mission of prospective leaders, however, then this is something that violates the basic objectives of Islamic law.

The protection offered by al-dharuriah al-khams [five fundamental needs] only considers the needs of human beings as mukallaf [religiously responsible or accountable], and it does not consider the protection and needs of society, the ummah or the country, as well as humanitarian relations. However, Al Qardhawi (2008) did not explicitly add new aspects to the five that have already existed. The Qur'an and the life practices of the Prophet SAW strongly emphasise the importance of making the Muslims one ummah, as well as the obligation to ensure that the ummah remains united and strong so that they would survive and even develop. This is what is known as Hifz Al-Ummah (Djazuli 2007).

Conclusion

Many Muslim youths in North Sumatra are resistant to non-Muslim leader candidates in the regional head elections, including the election of governors and mayors. Muslim youths have a high resistance to non-Muslim governor candidates and non-Muslim mayoral candidates because of the fear that non-Muslim leaders might forbid them to pray. Muslim youths have a high resistance to non-Muslim governor candidates and non-Muslim mayoral candidates because of the fear that non-Muslim leaders might policies that would lead to civil war. Muslim youth in North Sumatra receive much information that contains fear of non-Muslim leadership, both from social media and lectures conducted in the mosques about the importance of having Muslim leaders who are obedient to the teachings of Islam and the dangers of having non-Muslim leaders who cause difficulty for Muslims in carrying out worship (prayer, fasting, qurban [slaughter of animals as a form of taqwa to Allah SWT]) as exemplified by the leadership of the governor of DKI Jakarta and the Mayor of Surakarta. Muslim youths in North Sumatra also get various information from social media and lectures given by scholars at the mosque about the risk of war that occurs amongst Muslims if the majority of the Muslim community is led by non-Muslim leaders, providing various examples such as the war incident that occurred in Ambon and the case of criminalisation of ulama that occurred in DKI Jakarta.

Influencing people not to choose non-Muslim leaders happens not only through lectures, but also through social media, such as WhatsApp and Facebook, or banners and posters expressing the obligation to choose a leader of faith and the prohibition against choosing infidel leaders. This was circulated in the courtyard of the mosque, showing that the prohibition against choosing non-Muslim leaders is greater than the prohibition against adultery, eating pork and drinking alcohol.

Acknowledgements

The researchers thank Universitas Islam Negeri Sumatera, Utara, for providing an opportunity to carry out this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

M.S.A.N., S.S., H.M., P.A.S. and W.D. conceptualised the presented ideas. All authors jointly revised the manuscript based on the feedback from the reviewers.

Ethical considerations

This article followed all ethical standards for research without direct contact with human or animal subjects.

Funding information

This research received funding from the Ministry of Religious Affairs of the Republic of Indonesia.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the article.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

References

Abdullah, A., 2017, 'Read the political communication of the Islamic defense action movement 212: Between identity politics and alternative political Ijtihad', Jurnal An-nida 41(2), 202-212. https://doi.org/10.24014/an-nida.v41i2.4654 [ Links ]

Al-Ghazali, A.H., 2006, Al-Mustashfa min Ilm al-Usul, Maktabah at-Tijariyah, Beirut. [ Links ]

Ardipandanto, A., 2017, 'The election of Governor of DKI Jakarta 2017: Candidate politics strategy', Kajian 22(1), 15-31. https://doi.org/10.15642/JIIS.2019.13.2.454-479 [ Links ]

Atriana, R., 2017, Hakim: Ahok Merendahkan Surat Al-Maidah 51, viewed 10 March 2022, from https://news.detik.com/berita/d-3496149/hakim-ahok-merendahkan-surat-al-maidah-51 [ Links ]

Assyaukanie, L., 2019, 'Religion as a political tool secular and Islamist roles in Indonesian elections', Journal of Indonesian Islam 13(2), 454-479. https://doi.org/10.15642/JIIS.2019.13.2.454-479 [ Links ]

Azra, A., 2018, 'Kesalehan dan Politik: Islam Indonesia', Studia Islamika 25(3), 639-650. https://doi.org/10.15408/sdi.v25i3.9993 [ Links ]

Badan Pusat Statistik, 2018, Statistik Politik 2017, Jakarta. [ Links ]

Bahri, S., 2018, 'Non-Muslim leadership polemic in indonesia: Outcomes of Muktamar NU XXX at Lirboyo in 1999 and Bahtsul Masail Kiai Muda Ansor in 2017', Epistemé 13(2), 461-481. https://doi.org/10.21274/epis.2018.13.2.461-481 [ Links ]

Djazuli, H.A., 2007, Kaidah-kaidah Fikih Kaidah-kaidah Hukum Islam dalam Menyelesaikan Masalah-masalah yang Praktis H.A. Djazuli, Kencana, Jakarta. [ Links ]

Djuyandi, Y., 2017, 'Islamic fundamentalism in Dki Jakarta election in 2017', Jurnal Bawaslu 3(2), 1-10. [ Links ]

Elyta, E., 2021, 'Handling conflict through security in West Kalimantan', Jurnal Politik Profetik 9(2), 331-343. https://doi.org/10.24252/profetik.v9i2a9 [ Links ]

Fathoni, R., 2018, 'DKI Jakarta Public Voter Behavior in DKI Jakarta Governor Election in 2017', Journal of Politic and Government Studies 8(1), 271-280. [ Links ]

Fautanu, I., 2020, 'Political identity in DKI Jakarta election 2017: Perspective of Nurcholish Madjid political thinking', POLITICON: Jurnal Ilmu Politik 2(2), 87-112. https://doi.org/10.15575/politicon.v2i2.8146 [ Links ]

Fenton, A.J., 2016, 'Faith, intolerance, violence and bigotry: Legal and constitutional issues of freedom of religion in Indonesia', Journal of Indonesian Islam 10(2), 181-212. https://doi.org/10.15642/JIIS.2016.10.2.181-212 [ Links ]

Gammon, L., 2020, 'Is populism a threat to Indonesian democracy?', in T. Power & E. Warburton (eds.), Democracy in Indonesia: Stagnation in regression?, pp. 110-117, ISEAS Publishing, Singapore. [ Links ]

Hamid, I., 2020, 'Islam, local "strongmen," and multi-track diplomacies in building religious harmony in Papua', Journal of Indonesian Islam 14(1), 113-138. https://doi.org/10.15642/JIIS.2020.14.1.113-138 [ Links ]

Hasim, M., 2003, 'The Muslim scholars' work in building peace in West Kalimantan', Al-Qalam 19(1), 59-66. https://doi.org/10.31969/alq.v19i1.223 [ Links ]

Hasyim, S., 2019, 'Religious pluralism revisited: Discursive patterns of the Ulama Fatwa in Indonesia and Malaysia', Studia Islamika 26(3), 475-509. https://doi.org/10.36712/sdi.v26i3.10623 [ Links ]

Hendrastuti, R., 2019, 'Foreign media attitude to highlight Ahok's blasphemy case', Sawerigading 25(2), 75-84. https://doi.org/10.26499/sawer.v25i2.596 [ Links ]

Hidayatullah, R., 2021, 'Music, contentious politics, and identity: A cultural analysis of "Aksi Bela Islam" March in Jakarta (2016)', Studia Islamika 28(1), 53-96. https://doi.org/10.36712/sdi.v28i1.11140 [ Links ]

Huda, M.S., 2019, 'The local construction of religious blasphemy in East Java', Journal of Indonesian Islam 13(1), 96-114. https://doi.org/10.15642/JIIS.2019.13.1.96-114 [ Links ]

Ikhwan, H., 2018, 'Fitted Sharia in democratizing Indonesia', Journal of Indonesian Islam 12(1), 17-44. https://doi.org/10.15642/JIIS.2018.12.1.17-44 [ Links ]

Kharisma, T., 2017, 'Religious conflict in DKI Jakarta election in WhatsApp group with multicultural members', Jurnal Penelitian Komunikasi 20(2), 107-120. https://doi.org/10.20422/jpk.v20i2.233 [ Links ]

Kristianus, K., 2016, 'Politics and ethnic cultural strategies in elections Kalimantan', Politik Indonesia: Indonesian Political Science Review 1(1), 87-101. https://doi.org/10.15294/jpi.v1i1.9182 [ Links ]

Kurtz, L.R., 2008, Encyclopedia of violence, peace, and conflict, Academic Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Lestari, M., 2018, Candidate for Governor Edy gets support from the Islamic organization of Al-Washliyah, detik news, viewed 30 March 2022, from https://news.detik.com/news/d-4049475/cagub-edy-dapat-supportan-ormas-islam-al-washliyah. [ Links ]

Lukito, R., 2016, 'Islamisation as legal intolerance: The case of GARIS in Cianjur, West Java', Al-Jami'ah: Journal of Islamic Studies 54(2), 393-425. https://doi.org/10.14421/ajis.2016.542.393-425 [ Links ]

Lukito, R., 2021, 'The politics of syariatisation in Indonesia: MMI and GARIS' struggle for Islamic Law', Studia Islamika 28(2), 319-347. https://doi.org/10.36712/sdi.v28i2.15819 [ Links ]

Mahmuddin, R., 2017, 'Law to bury the bodies of blasphemy supporters and non-Muslim voters become leaders', NUKHBATUL 'ULUM: Jurnal Bidang Kajian Islam 3(1), 61-69. https://doi.org/10.36701/nukhbah.v3i1.24 [ Links ]

Majid, N., 2018, 'Religious implications in the Jakarta election 2017 (Review of Siyasah Syar'iyyah)', Jurnal Syariah Hukum Islam 1(2), 129-157. [ Links ]

Maksum, A., 2017, 'Discourses on Islam and democracy in Indonesia: A study on the intellectual debate between liberal Islam Network (JIL) and Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia (HTI)', Journal of Indonesian Islam 11(2), 405-422. https://doi.org/10.15642/JIIS.2017.11.2.405-422 [ Links ]

Marshall, P., 2018, 'The ambiguities of religious freedom in Indonesia', The Review of Faith & International Affairs 15(1), 85-96. https://doi.org/10.1080/15570274.2018.1433588 [ Links ]

Mietzner, M., 2018, 'Explaining the 2016 Islamist mobilisation in Indonesia: Religious intolerance, militant groups and the politics of accommodation', Asian Studies Review 42(3), 479-497. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357823.2018.1473335 [ Links ]

Minan, J., 2019, 'Front Pembela Islam (FPI) is a source of political power identity of DKI Jakarta election in 2017', Jurnal KAPemda 14(8), 1-16. [ Links ]

Muhamad, I., 2017, 'The existence of urgency and religious culture in achieving the objective of education in schools', Islam Transformatif: Journal of Islamic Studies 1(1), 55-62. https://doi.org/10.30983/it.v1i1.330 [ Links ]

Mukti, A., 2019, 'Ulama, mosques and democratic spaces struggle with religious elites ahead of simultaneous elections in 2018 in West Kalimantan', Al Marhalah 3(2), 65-80. https://doi.org/10.38153/alm.v3i2.32 [ Links ]

Murti, B., 2011, Tes Validitas dan Reliabilitas Pengukuran untuk Penelitian Kesehatan, Gadjah Mada University Press, Yogyakarta. [ Links ]

Mu'ti, A., 2019, 'The limits of religious freedom in Indonesia; with reference to the first pillar Ketuhanan Yang Maha Esa of Pancasila', Indonesian Journal of Islam and Muslim Societies 9(1), 111-134. https://doi.org/10.18326/ijims.v9i1.111-134 [ Links ]

Ngusmanto, N., 2016, 'Pilkada 2015 and Patronage practice among Bureaucrat in West Kalimantan, Indonesia', Asian Social Science 12(9), 236-243. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v12n9p236 [ Links ]

Ningsih, M.R., 2022, 'Ethnic politics post-Madura-Dayak conflict in Kotawingin Barat Regency, Central Kalimantan', Journal of Politic and Government Studies 11(1), 1-12. [ Links ]

Nurhajati, L., 2020, 'Islamist Newspeak the use of Arabic terms as a form of cultural hegemony in political communication by Muslim fundamentalist groups in Indonesia', Journal of Indonesian Islam 14(2), 287-308. https://doi.org/10.15642/JIIS.2020.14.2.287-308 [ Links ]

Nurlaelawati, E., 2016, 'For the sake of protecting religion: Apostasy and its Judicial Impact on Muslim's Marital Life in Indonesia', Journal of Indonesian Islam 10(1), 89-112. https://doi.org/10.15642/JIIS.2016.10.1.89-112 [ Links ]

Pababbari, M., 2009, Islam dan Politik Lokal Studi Sosiologis atas Tarekat Qadiriyah di Mandar, Padat Daya, Makassar. [ Links ]

Priatmojo, D., 2016, Nahdlatul Ulama Chooses Neutral in DKI Jakarta Election, Viva News, Jakarta, viewed 30 March 2022, from https://www.viva.co.id/berita/metro/832917-nahdlatul-ulama-pilih-netral-di-pilkada-dki?page=all&utm_medium=all-page. [ Links ]

Purba, S., 2018a, Al Washliyah Islamic organization solid supports Eramas in North Sumatra governor election, INewsSumut, viewed 30 March 2022, from https://sumut.inews.id/berita/organisasi-islam-al-washliyah-solid-dukung-eramas-di-pilgub-sumut. [ Links ]

Purba, S., 2018b, Meet Muslim leaders in Binjai, Edy promises to listen to people's aspirations, INewsSumut, viewed 30 March 2022, from https://sumut.inews.id/berita/temui-tokoh-muslim-di-binjai-edy-janji-dengar-aspirasi-umat. [ Links ]

Putra, F.M., 2019, 'Radicalization of religious issues in the election of Governor and Deputy Governor of DKI Jakarta in 2017', Journal of Politic and Government Studies 8(4), 131-140. [ Links ]

Qaradhawi, Y., 2008, Contemporary fatwas, Gema Insani Press, Jakarta. [ Links ]

Rangkuti, L., 2018, Ustaz Abdul Somad and Tengku Zulkarnain pray for Eramas during the Akbar Campaign, sindonews.com, viewed 30 March 2022, from https://daerah.sindonews.com/berita/1315776/191/ustaz-abdul-somad-dan-tengku-zulkarnain-doakan-eramas-saat-kampanye-akbar. [ Links ]

Rasyidin, A., 2016, 'Islamic organizations in North Sumatra: The politics of initial establishment and later development', Journal of Indonesian Islam 10(1), 63-88. https://doi.org/10.15642/JIIS.2016.10.1.63-88 [ Links ]

Riza, F., 2020, Urban Islamic activism (identity politicization, mobilization and political pragmatism, Pusdikra MJ, Medan. [ Links ]

Rochayati, N., 2010, 'Dynamics of local democracy in Southeast Asia decentralization, elections, and violent conflicts in Indonesia and the Philippines', Global: Jurnal Politik Internasional 10(2), 134-149. https://doi.org/10.7454/global.v10i2.277 [ Links ]

Sholikin, A., 2018, 'Political Islamic movement in Indonesia after action to defend Islam volumes I, II and III', Madani Jurnal Politik dan Sosial Kemasyarakatan 10(1), 12-33. [ Links ]

Simamora, S.D.V., 2019, 'Issues of ethnic identity and religion in political context (case of the 2018 North Sumatra Governor Election)', Interaksi Online 7(4), 317-329. [ Links ]

Simarmata, S.P., 2018, Hasyimsyah: There are many assumptions from Muhammadiyah that support ERAMAS, medanbisnisdaily, viewed 30 March 2022, from https://medanbisnisdaily.com/news/online/read/2018/04/29/34666/hasyimsyah_banyak_anggapan _muhammadiyah_mendukung_eramas/. [ Links ]

Sham, T., 2019, 'Form of Da'wah on Twitter ahead of DKI Jakarta election in 2017', J. Diskurs. Islam 7, 149-185. [ Links ]

Subarkah, M., 2018, KUI sumut recommendation: Muslims must play in politics, Republika.com, viewed 30 March 2022, from https://www.republika.co.id/berita/p6jozs385/rekomendasi-kui-sumut-muslim-harus-beperan-dalam-politik. [ Links ]

Sumaya, F., 2020, 'Identity in conflict in West Kalimantan (a conflict mapping)', Jurnal Kolaborasi Resolusi Konflik 2(2), 86-92. https://doi.org/10.24198/jkrk.v2i2.28149 [ Links ]

Suryadinata, M., 2015, 'Non-Muslim leadership in the Qur'an analysis of the FPI's interpretation of the verses of non-Muslim leaders', Ilmu Ushuluddin 2(3), 241-253. https://doi.org/10.15408/jiu.v2i3.2630 [ Links ]

Susetio, J., 2018, Ketua Bawaslu Sumut Safrida Tanggapi Spanduk Larangan Memilih Pemimpin Kafir, MedanTribun News, viewed 10 March 2022, from https://medan.tribunnews.com/2018/06/07/ketua-bawaslu-sumut-safrida-tanggapi-spanduk-larangan-memilih-pemimpin-kafir?page=all. [ Links ]

Syam, T., 2019, 'Form of Da'wah on Twitter Ahead of DKI Jakarta Election in 2017', Jurnal Diskursus Islam 7(1), 149-185. https://doi.org/10.24252/jdi.v7i1 [ Links ]

Syarif, A., 2021, 'Impact and new model of government split after West Kalimantan Governor election in 2018', Jurnal Papatung 4(1), 69-78. https://doi.org/10.54783/japp.v4i1.365 [ Links ]

Syatibi, A.S.I., 1990, Al-Muawafaqat Fi Ushul Al-Ahkam, Dar al-Kutub al-'Ilmiyyah, Beirut-Lubnan. [ Links ]

Tanthowi, P.U., 2019, 'Muhammadiyah and politics: Ideological foundation for constructive articulation', MAARIF 14(2), 93-113. https://doi.org/10.47651/mrf.v14i2.65 [ Links ]

Triana, R., 2020, 'Identity politics: Will identity politics affect popularity? (Study of identity politics in Kalteng elections)', Wacana Jurnal Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik 2(VIII), 163-172. [ Links ]

Zainuddin, M., 2015, 'Plurality of religion: Future challenges of religion and democracy in Indonesia', Journal of Indonesian Islam 9(2), 151-166. https://doi.org/10.15642/JIIS.2015.9.2.151-166 [ Links ]

Zakina, N.F.N., 2016, 'Ethnic politics and compliance gaining minority candidates in West Kalimantan Elections', Jurnal Komunikasi 1(2), 122-129. https://doi.org/10.25008/jkiski.v1i2.58 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Muhammad Nasution

muhammadsyukrialbani@uinsu.ac.id

Received: 09 Mar. 2022

Accepted: 14 Apr. 2022

Published: 09 June 2022