Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

HTS Theological Studies

versión On-line ISSN 2072-8050

versión impresa ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.78 no.4 Pretoria 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v78i4.7341

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Sanctuary schematics and temple ideology in the Hebrew Bible and Dead Sea Scrolls: The import of Numbers

Joshua J. Spoelstra

Department of Old and New Testament, Faculty of Theology, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The temple schematics in the Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS), that is, New Jerusalem and Temple Scroll, has often been comparatively examined with the sanctuary structures in the Hebrew Bible (HB) (Ezk 40-48 and Num 2). Typically, in scholarship, the irreconcilable differences between all accounts (regarding the size, shape, name-gate ordering, etc.) is underscored, thus rendering a literary conundrum. This article argues that New Jerusalem and Temple Scroll drew from both Ezekiel 40-48 and Numbers 2 in different ways, purporting the sect(s)'s theologies and ideologies which accords, further, with the life setting of the Qumran communities; the influence of Numbers in the DSS is underscored. These aspects include (1) the eastern orientation of sacred structures and the compound at Khirbet Qumran, (2) the precise locale of the communities at the Dead Sea vis-à-vis Ezekiel 47 and (3) the desert encampment configuration together with its militaristic overtones in Numbers, which corresponds to the DSS sect(s)'s apocalyptic expectations as indicated in the War Scroll. Consequently, the Qumran sect(s) truly saw itself as an alternative priesthood of the forthcoming restored temple of God, even as in the interim they functioned as an alternative sanctuary (4QFlor; 4QMMT; 1QS). The import of Numbers upon the DSS sect(s)'s temple ideologies and priestly theologies is, therefore, equivalent to that of Ezekiel.

CONTRIBUTION: This article traces theological themes of temple and priestly ideologies between and among the Qumran literature and Hebrew Scriptures; both the respective library or canon and methodological approach are core to the historical thought's aim and scope of HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies

Keywords: New Jerusalem; Temple Scroll; Ezekiel 40-48; Numbers 2; wilderness sanctuary; temple; theology; ideology.

Introduction

The Hebrew Bible (HB) and Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS) share distinctive texts related to sanctuary schematics and temple ideology. Based on the essentially analogous form and genre, the Vorlage of the DSS's literary temples, both New Jerusalem (4Q554-555) and Temple Scroll (11QT),1 is ostensibly Ezekiel 40-48 because Ezekiel's vision of a divinely blueprinted temple complex is unique in the HB (Angel 2018:354-357; Langlois 2018:332; cf. Hals 1989:285-287). Nevertheless, the Israelite tribal encampment schema around the tent of meeting, in Numbers 2:1-34 and 10:11-28,2 is also germane - the tabernacle complex is, after all, divinely blueprinted architecture (Ex 25-31). Whereas it is routine to include Numbers 2 in such a comparative analysis (Puech 2009:92-93), the author maintains that the wilderness sanctuary, with its organisational arrangement and rationale thereof, had a greater value and import to the Qumran sect(s)3 than has previously been appreciated by scholars.

In this article, the author argues that the DSS sect(s), influenced and inspired evenly by Numbers 2 and Ezekiel 40-48, crafted their temple schematic documents with multifarious ideologies and theologies (Jobling & Pippin 1992; Schmid 2015; cf. Brooke 2013:211-227; Zahn 2018:330-342) not only registering in New Jerusalem and Temple Scroll but also reverberating palpably in other scrolls. The course of investigation shall proceed from synchronic analysis, which juxtaposes New Jerusalem and Temple Scroll with Ezekiel 40-48 and Numbers 2. Subsequently, a diachronic examination seeks to ascertain the temple ideologies and priestly theologies, which informed the Qumran sect(s)'s communal life and social location, as well as its modus operandi in interacting with their religious milieu and expectations of the future. Ultimately, the author's aim was to underscore why the DSS sect(s), in producing schematics of temple structures both similar and yet quite dissimilar to its biblical parallels, purposefully analogised their existence and writings with the ethos of the Israelites' erstwhile wilderness experience as depicted in the book of Numbers.

Synchronic assessment

Several monographs have been written, which comparatively analyse New Jerusalem and Temple Scroll vis-à-vis their biblical counterparts of Ezekiel 40-48 and Numbers 2 (Chyutin 1997; DiTommaso 2005; García Martínez 1999:431-460; Maier 1985; Schiffman 2008; White Crawford 2000; Wise 1990; Yadin 1985; cf. Swarup 2006:151-164); consequently, the present synchronic analysis may be succinct. Here, a few crucial, interrelated architectural configurations of the four sanctuary structures shall be elucidated. These synthetic observations purport priestly and cultic priorities in and for the Qumran communities.

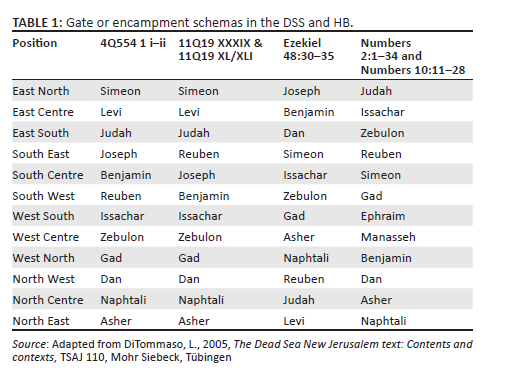

Firstly, the sequence of named gates at the perimeter of the sacred structures serve as an entry point into the discussion of key architectural configurations towards diachronic interpretation. The uniform name-gate assignment of New Jerusalem and Temple Scroll is widely divergent from that of Ezekiel 48; nonetheless, all three texts have gates named after the 12 sons of Israel, three per side. Numbers 2, instead, enumerates the 12 tribes of Israel encamped in three divisions adjacent to each of the four sides of the tabernacle. Table 1 tabulates the name-gate sequence in New Jerusalem (4Q554-555), Temple Scroll (11QT) and Ezekiel's temple vision (Ezk 48), as well as the Israelite tribal encampment schema (Num 2).

Secondly, the eastern entrance(s) is underscored. In all four texts, the sanctuary schematics are described by the seer and narrator who surveys the thresholds in a clockwise succession from an aerial perspective, as it were. Typically, the east wall is the starting point, as is the case in 4Q554, 11QT and Numbers 2 (see Antonissen 2010:496). Common to this leading cardinal point is the tribe of Judah, which highlights the monarchy; the tribe of Levi, which represents the priesthood, also features on the east side in 4Q554-555 and 11QT (Noth 1968:24). In the case of Ezekiel 48:30-35, 'the northern side of the "contributed city" is the most important, because it faces the Temple, and consequently the gates of Levi and Judah are placed in this wall' (Chyutin 1997:81; cf. Ezk 42:15-19).

Thirdly, Levi - viz. the priesthood - is especially emphasised in all four texts. Not only is Levi located on the prominent walls (whether east or north) in New Jerusalem and Ezekiel 40-48 but also in Numbers 2 and Temple Scroll Levi occupies the nucleus of the sacred space. In Numbers 2, the Levitical families of the Gershomites, Merarites, Kohathites and Aaronites encamp at the centre of the tribal orbit around the tabernacle (Num 2:17), and in the Temple Scroll, there are four gates set in the inner wall of the temple, entering the most holy space at the epicentre, which presumably represent the four families of Levi. Schiffman (2008) affirms this connection, stating:

These gates [of the Inner Court], as can be determined by comparison with the apportionment of chambers on the outside wall of the Outer Court, represented the four groups of the tribe of Levi, the Aaronide priests on the east, and the Levites of Kohath on the south, Gershon on the west and Merari on the north. This arrangement corresponds exactly to the pattern of the desert camp as described in Num. 3:14-39. (p. 218)

Thus, Temple Scroll represents a fusion as it concerns Levi, correlating with all exterior walls of a sacred structure (per New Jerusalem and Ezk 48) and an inner sanctum (per Num 2).

Finally, the shapes of the four sanctuary structures are significant. Whereas the temple structure in Temple Scroll (280 × 280, 480 × 480, 1600 × 1600 cubits) and Ezekiel 48 (500 × 500 cubits) is square (Maier 1989:24-34; cf. Yadin 1985:147-148), the sacred architecture in New Jerusalem (100×150 ris) and Numbers 2 (50×100 cubits) is rectangular (Antonissen 2010:489-494; Chyutin 1997:76-77; Dozeman 2009:608). Therefore, it appears that each scroll tradition draws from both Ezekiel and Numbers, yet appropriates those biblical texts in alternate ways.

Diachronic development

The preceding synchronic evaluation provides the basis for diachronic analysis. In tracing the diachronic developments of temple and priesthood theology within the Qumran sect(s), additional sectarian scrolls shall be considered to map the sect(s)'s ideological constellation of certitudes and practices. Thus, the eastern orientation of biblical sacred structures and the sect(s)'s own social location vis-à-vis Ezekiel shall be examined; also, alternative, spiritual temples and issues of an anticipated apocalyptic battle with priests have underpinnings in Numbers. Numbers, as argued, is a significant Vorlage for the Qumran sect(s), at least as important as Ezekiel in their experience.

Ideological-theological extrapolations of eastern oriented sacred structures

Chyutin (1997:104-106) has observed how, throughout the Israelite and Jewish history, the tabernacle, temple and many synagogues were all positioned so that the (main) entrance faced east. In his biblical analysis and comparison of ancient near Eastern counterparts, the reason for such a pattern of eastern orientation has correspondence with the direction of the sunrise (Num 2:3; 3:38). Intriguingly, the Qumran sect(s), who built a compound at Khirbet Qumran, appear to conform to this design. According to archaeological evidence, the sectarian compound featured 'three major quarters: the eastern [side being its] "main building"' (Regev 2009:88) - just as nearly every sanctum was facing eastwards (cf. Magness 2002:127-129).

Furthermore, in the context of Ezekiel's vision of the new temple (Ezk 40-48), the seer views a life-giving stream flowing from the threshold of the envisioned temple. As water emanates from the place of God's presence, it flows progressively eastward until it drains into the Dead Sea, transforming its stagnant waters (Ezk 47:1-12).4 It is 'probabl[e]' that the sect(s) responsible for the DSS intentionally located themselves at Qumran based, at least in part, on this Ezekiel text (Cook 2018:265). Khirbet Qumran is even adjacent to the wadi Qumran, when, in the event of winter rains, waters were diverted from the wadi to resource the sectarian compound, using it for ritual cleansing. Although it is conjecture, the yaḥad may have patterned their move to the desert after Ezekiel 10-11, where God's glory steadily departs from the temple and Jerusalem on an easterly vector (cf. 1QM 1:2-3). Regardless, it appears the yaḥad believed it must move to the desert to perform its sacrosanct duties, as 1QS 8-9 cites Isa 40:3 (to prepare the way of the LORD in the wilderness) in justification (Brooke 2018:121; Hultgren 2007:313-316). Perhaps, the yaḥad even awaited God's coming from the east to enter the new temple (Ezk 43:1-5), as pursuant elements will be argued.

The Yaḥad and alternative temples

It has been shown that New Jerusalem and Temple Scroll has been markedly influenced by Numbers 2; but is not the life of the Qumran sect(s) also affected, even inspired, by the desert sanctuary and encampment schema? Schiffman (2008:228) had questioned why the author of 11QT 'chose to pattern his Temple after the desert camp, and exactly how he saw the structure and function of that camp'. In what follows, the author proposes a particularised interpretation of the purpose of the desert camp and desert sanctuary, as portrayed in Numbers.

It should not be overlooked that the DSS sect(s), by virtue of residing at (Khirbet) Qumran, lived in the desert. In addition, it should be reiterated that this social location accords with the terminal point of the transformative river issuing from the Temple, as per Ezekiel 47. Furthermore, in the so-called halakic letter, an ideological analogue is made between the Jerusalem Temple and the tent of meeting - the one tantamount to the other. 4QMMT (B29-31a, 60-62) reads:

And we think that the Temple [is the tent of meeting, and Jerusalem] is the camp; and outside the camp [is outside of Jerusalem;] it is the camp of their cities. …Jerusalem is the holy camp and it is the place he has chosen among all the tribes of Israel. For Jerusalem is the head of the camps of Israel. (Von Weissenberg 2009:122-124)

Florilegium (4Q174 3:6), moreover, appositionally asserts that the sectarians are a temple of humankind (cf. Regev 2018:604-631; Swarup 2006:121-123); relatedly, the Manual of Discipline (1QS 8:5-6; 9:6) makes a similar claim: the yaḥad is a holy of holies (cf. Eckhardt 2017:407-423; Newsom 2004:156-159). These set of data have crucial implications.

Based on the historical setting, the implicit thrust of these passages indicates that the Qumran sect(s) view themselves as correct in halakha and ritually, cultically pure - in contradistinction to the defiled priesthood in Jerusalem and its polluted temple (Angel 2010:212-242; Regev 2003:243-278). Clearly, the DSS sect(s) had ambitions for and advocated itself as the truest form of the priesthood (Fabry 2010:243-262; Kugler 1999:93-116). It is thus provocative that an alternative priesthood with a functioning cultic system was tabernacling in the wilderness, anticipating the re-establishment of the ideal temple and the pristine priesthood in Jerusalem - just as the sect(s) were conceiving it in their writings and practising it in their order(s).

The Sons of Light vis-à-vis tribal encampment formations

Another reason the composers of New Jerusalem and Temple Scroll drew handily from Numbers (in addition to Ezekiel) was to appropriate the aspects of warfare, which accorded well with the Qumran sect(s)'s own eschatological understanding. The War Scroll (1QM) anticipates an apocalyptic battle where the Sons of Light (cf. also 1QS) face the Sons of Darkness led by Belial (cf. also 4QFlor). Furthermore, there are several significant militaristic parallels found between Numbers and War Scroll5; these include battle trumpets (Num 10:1-10 // 1QM 2:15-3:11), company banners (Num 2:2-34; 10:14-25 // 1QM 3:13-5:2) and orders on the deployment of military ranks (Num 10:11-28; 33:1 // 1QM 5:3-6:17).

Moreover, direct quotations from Numbers are found in the chief priest's address (Num 10:9 in 1QM 10:6-8) and prayer (Num 24:17-19 in 1QM 11:6-7) before battle; the former instance cites the biblical command to blow the trumpet to mobilise Israelite troops and the latter quotes Balaam's oracle of a forthcoming Israelite waring ruler (cf. Jassen 2015:194-195). This may refer to the Prince of Light in 1QM 13:10 (Hogeterp 2009:439), or more specifically, the Davidic messiah in 4QpIsaa, the Isaiah pesher (cf. Batsch 2010:175; Elgvin 2015:334-335); irrespective of this, it is evocative that the figure referenced in Numbers 24 - metonymically as star and sceptre - is considered to be an allusion to the messiah (see e.g. Grossfeld 1988:138). Lastly, 4QM (4Q491B frgs. 1-3:1) allegorically refers to the foe as an archetypal defiler, calling them Korah and his congregation (cf. Schultz 2009:376-379); this sectarian superiority is discerned in 4QMMT too.

The wilderness experience, thus, depicted in Numbers, indeed, appealed to the Qumran sect(s), as encamped brethren in the desert, engaged in a cultic system as elite priests and preparing for an apocalyptic battle (at least literarily). The kingly messianic figure of Davidic descent who assists the priests and carries the eschatological battle to victory (cf. Bertalotto 2011:327) - with the mighty hand of God - has underpinnings in the second most important gate or position of the tribe or son of Judah in New Jerusalem and Temple Scroll, Ezekiel 40-48 and Numbers 2. Consequently, the rubric of Numbers, as it relates to the organisation and roles of Israel - especially the priests - in the milieu of the wilderness sanctuary, resonates in the major (viz. the lengthiest) scrolls in the DSS repository: 11QT and 1QM (cf. Regev 2011:42; White Crawford 2016:123).

Conclusion

A harmonising interpretation has been proposed, herein, along the lines of theology and ideology concerning the temple structures in New Jerusalem and Temple Scroll vis-à-vis Ezekiel 40-48 and Number 2. By comparing the analogous sanctuary schematics in terms of shape (rectangle and square), name-gate or encampment sequence of the sons or tribes of Israel and orientation (eastward), it is evident that the priestly and monarchic tribes (Levi and Judah, respectively) are a priority in the HB and DSS. For the Qumran sect(s), this purported to the shaping of their life setting. The compound at Khirbet Qumran was oriented eastward like that of the sacred structures in 4Q554-555, 11QT and Number 2; the precise locale of the Qumran sect(s) along a wadi at the Dead Sea accords specifically with a paradisiacal vision in Ezekiel 47, a place of a significantly regenerative work of God; the desert encampment configuration together with its militaristic overtones in Numbers corresponds to the Qumran sect(s)'s apocalyptic expectations as indicated in the War Scroll, a document that encapsulated ideologies of priesthood as do scrolls pertaining to temple schematics. Consequently, the Qumran sect(s) crafted texts about temples, physical (4Q554-555; 11QT) and spiritual (4QFlor; 4QMMT; 1QS), while preparing themselves as Sons of Light to fight the Sons of Darkness (1QM). Therefore, the desert sanctuary of Numbers aligns with and approximates the DSS sect(s)'s social location and Manual of Discipline or life setting; possibly, they awaited God's coming or visitation (cf. Ezk 43:1-5; Is 40:3) where God would enter the eschatological temple of their own design(s). The influence of Numbers should, therefore, be appraised as equivalent to Ezekiel in the DSS sect(s)'s temple ideologies and priestly theologies.

Acknowledgements

The author dedicates this article to the memory of Peter W. Flint, his teacher in the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

Author's contributions

J.J.S. is the sole author of this research article.

Ethical considerations

This study followed all ethical standards for research without direct contact with human or animal subjects.

Funding information

This research work received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the author.

References

Angel, J.L., 2010, Otherworldly and eschatological priesthood in the Dead Sea Scrolls, STDJ 86, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Angel, J.L., 2018, 'Temple Scroll', in G.J. Brooke & C. Hempel (eds.), T&T Clark companion to the Dead Sea Scrolls, pp. 354-357, London, Bloomsbury. [ Links ]

Antonissen, H., 2010, 'Architectural representation technique in New Jerusalem, Ezekiel and the Temple Scroll', in K. Berthelot & D. Stökl Ben Ezra (eds.), Aramaica Qumranica: Proceedings of the Conference on the Aramaic Texts from Qumran in Aix-en-Provence 30 June-2 July 2008, STDJ 94, pp. 485-513, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Batsch, C., 2010, 'Priests in warfare in Second Temple Judaism: 1QM, or the Anti-Phinehas', in D.K. Falk, S. Metso, D.W. Parry & E.J.C. Tigchelaar (eds.), Qumran Cave 1 revisited: Texts from Cave 1 sixty years after their discovery: Proceedings of the Sixth Meeting of the IOQS in Ljubljana, STDJ 91, pp. 165-178, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Bertalotto, P., 2011, 'Qumran Messianism, Melchizedek, and the Son of Man', in A. Lange, E. Tov & M. Weigold (eds.), The Dead Sea Scrolls in context: Integrating the Dead Sea Scrolls in the study of ancient texts, languages, and cultures, VTSup 140/141, pp. 325-339, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Blenkinsopp, J., 1990, Ezekiel (interpretation), John Knox, Louisville, KY. [ Links ]

Brooke, G.J., 2013, Reading the Dead Sea Scrolls: Essays in method (EJIL 39), SBL Press, Atlanta, GA. [ Links ]

Brooke, G.J., 2018, 'Isaiah 40:3 and the wilderness community', in G. Brook & F. García Martínez (eds.), New Qumran texts and studies: Proceedings of the First Meeting of the International Organization for Qumran Studies, Paris 1992, STDJ 15, pp. 117-132, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Chyutin, M., 1997, The New Jerusalem Scroll from Qumran: A comprehensive reconstruction, JSPSupp 25, Sheffield, Sheffield Academic Press. [ Links ]

Collins, J.J., 2009, 'Beyond the Qumran Community: Social organization in the Dead Sea Scrolls', DSD 16, 351-369. [ Links ]

Cook, S.L., 2018, Ezekiel 38-48 (AB 22B), Yale University Press, New Haven, CT. [ Links ]

DiTommaso, L., 2005, The Dead Sea New Jerusalem text: Contents and contexts, TSAJ 110, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen. [ Links ]

Dozeman, T.B., 2009, Exodus (ECC), Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Eckhardt, B., 2017, 'Temple ideology and Hellenistic private associations', DSD 24, 407-423. [ Links ]

Elgvin, T., 2010, 'Temple mysticism and the temple of men', in C. Hempel (ed.), The Dead Sea Scrolls: Texts and context, STDJ 90, pp. 227-242, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Elgvin, T., 2015, 'Violence, apologetics, and resistance: Hasmonaean ideology and Yaḥad texts in dialogue', in K. Davis, K.S. Baek, P.W. Flint & D. Peters (eds.), The War Scroll, violence, war and peace in the Dead Sea Scrolls and related literature: Essays in honour of Martin G. Abegg on the occasion of His 65th birthday, STDJ 115, pp. 319-340, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Fabry, H.-J., 2010, 'Priests at Qumran: A Reassessment', in C. Hempel (ed.), The Dead Sea Scrolls: Texts and context, STDJ 90, pp. 243-262, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

García Martínez, F., 1999, 'The Temple Scroll and the New Jerusalem', in P.W. Flint & J.C. VanderKam (eds.), The Dead Sea Scrolls after fifty years: A comprehensive assessment, pp. 431-460, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Grossfeld, B., 1988, The Targum Onqelos to Leviticus and the Targum Onqelos to Numbers (ArBib 8), Liturgical Press, Collegeville, MN. [ Links ]

Hals, R.M., 1989, Ezekiel, FOTL 19, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Hogeterp, A., 2009, Expectations of the end: A comparative traditio-historical study of Eschatological, Apocalyptic and Messianic ideas in the Dead Sea Scrolls and the New Testament, STDJ 83, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Hultgren, S., 2007, From the Damascus Covenant to the Covenant of the community: Literary, historical, and theological studies in the Dead Sea Scrolls, STDJ 66, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Jassen, A.P., 2015, 'Violent imaginaries and practical violence in the War Scroll', in K. Davis, K.S. Baek, P.W. Flint & D. Peters (eds.), The War Scroll, violence, war and peace in the Dead Sea Scrolls and related literature: Essays in Honour of Martin G. Abegg on the occasion of His 65th birthday, STDJ 115, pp. 175-203, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Jobling, D. & Pippin, T. (eds.), 1992, Ideological criticism of biblical texts, SemeiaSup 59, Scholars Press, Atlanta, GA. [ Links ]

Kugler, R.A., 1999, 'Priesthood at Qumran', in P.W. Flint & J.C. VanderKam (eds.), The Dead Sea Scrolls after fifty years: A comprehensive assessment, pp. 93-116, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Langlois, M., 2018, 'New Jerusalem', in G.J. Brooke & C. Hempel (eds.), T&T Clark companion to the Dead Sea Scrolls, pp. 332-334, Bloomsbury, London. [ Links ]

Magness, J., 2002, The archaeology of Qumran and the Dead Sea Scrolls, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Maier, J., 1985, The Temple Scroll: An introduction, translation & commentary, JSOT Supp 34, JSOT Press, Sheffield. [ Links ]

Maier, J., 1989, 'The architectural history of the temple in Jerusalem in the Light of the Temple Scroll', in G.J. Brooke (ed.) Temple Scroll studies: Papers presented at the International Symposium on the Temple Scroll, Manchester, December 1987, JSPSupp 7, pp. 23-62, Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield. [ Links ]

Newsom, C., 2004, The self as symbolic space: Constructing identity and community at Qumran, STDJ 52, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Noth, M., 1968, Numbers: A Commentary (OTL), transl. J.D. Martin, Westminster, Philadelphia, PA. [ Links ]

Puech, É., 2009, Qumrân Grotte 4 XXVII (DJD XXXVII), Clarendon, Oxford. [ Links ]

Regev, E., 2003, 'Abominated temple and a holy community: The formation of the notions of purity and impurity in Qumran', DSD 10, 243-278. [ Links ]

Regev, E., 2009, 'Access analysis of Khirbet Qumran: Reading spatial organization and social boundaries', BASOR 355, 85-99. [ Links ]

Regev, E., 2011, 'What kind of sect was the Yaḥad? A comparative approach', in A.D. Roitman, L.H. Schiffman & S. Tzoref (eds.), The Dead Sea Scrolls and contemporary culture: Proceedings of the International Conference Held at the Israel Museum, Jerusalem (July 6-8, 2008), STDJ 93, pp. 41-58, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Regev, E., 2013, 'How many sects were in the Qumran movement? On the differences between the Yahad, the Damascus Covenant, the Essenes, and Kh. Qumran', Cathedra 148, 7-40. [ Links ]

Regev, E., 2018, 'Community as temple: Revisiting cultic metaphors in Qumran and the New Testament', BBR 28, 604-631. [ Links ]

Schiffman, L.H., 2008, The courtyards of the house of the Lord: Studies on the Temple Scroll, STDJ 75, in F. García Martínez (ed.), Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Schmid, K., 2015, Is there theology in the Hebrew Bible?, transl. P. Altmann, Eisenbrauns, Winona Lake, IN. [ Links ]

Schultz, B., 2009, Conquering the world: The War Scroll (1QM) reconsidered, STDJ 76, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Swarup, P., 2006, The self-understanding of the Dead Sea Scrolls community: An eternal planting, A house of holiness, LSTS 59, T&T Clark, London. [ Links ]

Von Weissenberg, H., 2009, 4QMMT: Reevaluating the text, the function, and the meaning of the epilogue, STDJ 82, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

White Crawford, S., 2000, The Temple Scroll and related texts, Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield. [ Links ]

White Crawford, S., 2016, 'The Qumran collection as a scribal library', in S. White Crawford & C. Wassen (eds.), The Dead Sea Scrolls at Qumran and the concept of a library, STDH 116, pp. 109-131, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Wise, M.O., 1990, A critical study of the Temple Scroll from Qumran Cave 11, SAOC 49, The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, Chicago, IL. [ Links ]

Yadin, Y., 1985, The Temple Scroll: The hidden law of the Dead Sea Sect, Random House, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Zahn, M.M., 2018, 'Exegesis, ideology, and literary history in the Temple Scroll: The case of the temple plan', in B.Y. Goldstein, M. Segal & G.J. Brooke (eds.), Hā-'îsh Mōshe: Studies in scriptural interpretation in the Dead Sea Scrolls and related literature in Honor of Moshe J. Bernstein, STDJ 122, pp. 330-342, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Joshua Spoelstra

josh.spoelstra@gmail.com

Received: 10 Jan. 2022

Accepted: 04 Apr. 2022

Published: 12 May 2022

1 . For concision, New Jerusalem is referred to as 4Q554-555 throughout because it is the longest extant version regarding named gates, although there are multiple manuscripts of the same: 1Q32, 2Q24, 5Q15, and 11Q18. Also, Temple Scroll, 11Q19-20, is herein either abbreviated 11QT or shortened to 11Q19 (again because this is the named gate section).

2 . For convenience, Numbers 2 will be referenced alone as representing the conceptual design of the tabernacle complex.

3 . There were several yahads both at Qumran and elsewhere (e.g. Collins 2009:351-369) and at Qumran there were at least a couple related yet distinct communities (e.g. Regev 2013:7-40); therefore, the author has used general terms (e.g. Qumran/DSS sect[s], sectarians, communities) interrelatedly for harmonising treatment to identify a constellation of theologies and ideologies related to priesthood and sanctuary. Furthermore, the author maintains that the DSS were produced (at least in large part) at Qumran by the various sectarians (cf. Magness 2002:32-44).

4 . Although the Dead Sea is not mentioned by name, it is metonymically so indicated; see, for example, Blenkinsopp (1990:231). Also, the paradisiacal vision of Ezekiel 47:1-12 together with the mythology of the garden of Eden/God in Ezekiel 28/31 reverberates through the sectarian writings (cf. Elgvin 2010:238-241).

5 . For connection between New Jerusalem and War Scroll, see DiTommaso (2005:117-118); García Martínez (1999:455).