Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

HTS Theological Studies

On-line version ISSN 2072-8050

Print version ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.78 n.3 Pretoria 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v78i3.7530

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v78i3.7530

Transcending invisible lanes through inclusion of athletics memories in archival systems in South Africa

Joseph Matshotshwane; Mpho Ngoepe

Department of Information Science, Faculty of Arts, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

In countries like South Africa, sports have the power to transcend invisible lanes of politics and race and thus inspire citizens to come together. Sport, including athletics, has been demonstrated as an instrument of solidarity of fragmented cultures. However, while sport is of such significance, it is still minimally represented in public archival holdings in South Africa. Despite the mandate to transform the archival system, evidence suggests that much of the memories of sports heroes, especially that of athletes, have not been recorded. This qualitative study utilised oral history as a research method to explore the feasibility of building inclusive archives through the collection of sports memories. Athlete participants were identified through snowball sampling and data were collected using both oral testimony interviews from athletes with first-hand information and oral tradition augmented through document analysis. The results of the study indicated that there are stories and memories of many great South African distance runners that must be told and included in the archive repositories. Sadly, these stories have not been recorded in written words, as there is a tendency to perpetuate elitism by documenting mostly oral history of prominent members of society with political power. The study revealed that most of athletes' memories from their running careers include certificates, trophies, medals, Springbok jerseys, newspaper clippings and pictures in their possession. It is concluded that until these sports archives and objects are considered as an important and unique element of South African history, they will forever be lost.

CONTRIBUTION: This study makes a contribution to the ongoing discourse of building inclusive archives in South Africa through the collection of athletics memories. The study is linked to the scope of the journal through propagating the inclusion of marginalised voices of athletics sports memories in mainstream archives

Keywords: inclusive archives; road running; memory; non-public records; sports archives; athletics; sports stories.

Introduction

It is no secret that in most South African public archive repositories, archival holdings mainly reflect colonial and apartheid records, and therefore do not give the full picture of the rainbow nation as the country is known. Harris (2001) argues that while archivists should play a neutral role, they often relate their position to the policy requirements of the government of the day. As a result, the records collected reflect the activities of the government. Jimerson (2007:267) argues that the problem with the former colonised groups 'is not that their history under foreign control has been forgotten, but that it was never recorded, therefore not remembered officially'. This happens because in most instances archival holdings are built to be aligned with the views and biases to favour those who are in charge in a particular period. Therefore, because of their undocumented history most disadvantaged communities continue to be marginalised to the periphery of mainstream archives. Consequently, as long as archival holdings only reflect colonial history, the country is also colonised and controlled in a way. Derrida and Prenowitz (1995:4) state that 'there is no political power without control of the archives, if not of memory'. Ketelaar (1992:5) puts it differently by saying, the 'cruel paradox in many revolutions is that what is left after revolution resembles the past'. This is true to the South African situation, as an analysis by Archival Platform (2015) revealed a national archival system that still reflects the colonial era. After 28 years of democratisation, most archival holdings in South Africa still reflect the apartheid conditions of the 1980s and Bantustan subsidiaries' archival service (Harris 2014:90) with 'archives remaining to be the realm of the elites' (Archival Platform 2015:v).

There has been a call to transform the situation so that the people can use archives and as Ketelaar (1992:4) reckons, archives can then 'become archives of the people for the people by the people'. Citizens will only use archives when they are considered relevant and are made accessible. In South Africa, this can be rectified as the archival legislation propagates for the collection of non-public records valuable to the country to fill the gaps that stem from the colonial era. For example, section 3(d) of the National Archives and Records Service of South Africa (NARSSA) Act (Act No. 43 of 1996) states that:

NARSSA should collect non-public records with an enduring value of national significance which cannot be more appropriately preserved by another institution, with due regard to the need to document aspects of the nation's experiences that had been neglected by archives repositories in the past.

The 1996 Archives Act has, as one of its objectives, the active documentation of the voices and the experiences of those either excluded from or marginalised during the colonial and apartheid-era (Archival Platform 2015). This can be done by documenting the experiences and the voices of previously marginalised groups to contribute towards inclusive archives. Inclusive archives are more focused on the archival collection of the marginalised to build archival holdings that include all people, whether poor or rich, black or white, kings or commoners (Wetli 2019). One way of building inclusive archives can be through the collection of athletics memories, as this area has not been fully explored in South Africa.

Although there are some private and public archives in South Africa which have already embarked on the collection of sports archives, Venter (2016) alludes that there is still a shortage of sports archives because of the non-structure of what is worth preserving. One example worth mentioning because of its focus on inclusivity is the Wits Historical Paper focused on Non-Racial Sports History Project in Transvaal from 1969 to 2005. The primary mandate of this project was to record the histories of non-racial sport from grassroots: clubs and their administrators and players, provincial and national histories, paying special attention to the role played by women. Established in 1992, the South African Non-Racial Olympic Committee also initiated a sports archival collection housed in different locations and mostly focused on sports activist Dennis Brutus and his campaign of fighting racial segregation in sport in South Africa to his advocacy for the expulsion of South Africa in the Olympics. Furthermore, the University of Cape Town has a sports collection of university sports teams. Over the latter discourse in shortage of sports archives because of the non-structure of what is worth preserving it becomes apparent that preliminary sports collections available are more focused on the administrative part of sports and not the memorialisation of athletes. This is also the case with organisations such as Athletics South Africa and the South African Sports Confederation and Olympic Committee as it became clear during the conduct of this study; the officials there indicated that they do not keep records relating to a specific athlete, except when it relates to doping and qualifications for competitions like the Olympics.

Although athletes' histories are part of non-public records, except where some histories in the form of certificates or funding are from government, they are often excluded in mainstream archives. It should also be noted that non-public records are not featured in the appraisal policies and guidelines of the national archives or provincial archives. Mostly in the past, non-public records of prominent people were donated and accepted in the archives resulting in memories of mostly the elites being preserved (Ngoepe 2019). To compound the problem, guidelines for implementation on how to collect non-public records are absent, which makes it even difficult to determine if athletics memories meet the criteria of non-public records with enduring value or not.

It should be noted that this is only a small fraction as not all people are interested in the sport. However, the sport has been demonstrated as an instrument of solidarity of fragmented cultures. For example, the late president Nelson Mandela (1918-2013) utilised the Rugby World Cup of 1995 as one of the tools to reconcile and unite a divided nation, as also reflected in the movie Invictus where he was played by Morgan Freeman. This has also been the case with the 2010 Federation Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) World Cup hosted by the South African Football Association (SAFA). As the hosting nation of the world soccer tournament, South Africans were united across racial lines. In South Africa, sport has humanised a great many people who had nothing to be excited about and perpetuated the anti-apartheid struggle (Alegi & Bolsmann 2010). This has also been the case with ultra-marathons in South Africa such as the Two Oceans Marathon1 and the Comrades Marathon2 where people from diverse backgrounds and racial lines gather to cheer the athletes on. Throughout the 20th century, sport became the concept that brought divided nations together and succeeded in the endeavours to bring solidarity in nations (Tassiopoulosa & Haydam 2008).

Therefore, it is the view of the researchers that sporting activities may be used successfully towards building inclusive archives as many people appeal to sports in different codes. This study explores the feasibility of building inclusive archives through the collection of athletics memories in South Africa. For the purpose of this study, the focus will only be on athletics. As Ngoepe (2020) would attest, road running is one of the most marginalised sporting activities in terms of sponsorships and memorialisation.

Problem statement

Despite the mandate to transform South African archives, evidence suggests that very little has been done in the national archival system. As with all social space, South Africa under apartheid, the terrain of social memory, was a site of struggle. This situation needs to change to attract new users to archives as archives should provide a context from which people can draw an enduring communal identity. Archival collections originating from marginalised groups should be pursued to secure and enrich the country's heritage by documenting the history and experiences of the under-documented (Rodrigues 2013). Sports archives are among the areas that could be used to add up to the transformation of archival holdings. Sport has always received considerable attention on social media and other public platforms, in general, uniting people and being the prestige of the nation. Despite this, there is still a shortage of sports archives in South Africa (Venter 2016). Hence, Ngoepe (2019, 2020) questions the whereabouts of records that resulted from sporting events hosted in South Africa, such as the FIFA 2010 World Cup, the 1995 Rugby World Cup and the All-Africa Games in 1999. Such records can be preserved and made available to the public. The existing sports records created daily by multiple organisations, including the South African Broadcasting Company, are normally out of public reach and contain only sports archives of broadcasted professional sports games, ignoring the sports records of the marginalised people, which in the case of this study, are black people.

Purpose and objectives of the study

The purpose of this study was to explore the feasibility of building an inclusive archive through the collection of athletics sports memories in South Africa. The specific objectives were to:

-

Describe ways of gathering memories of previously excluded athletes to include them in the national archival system.

-

Determine the location, custody and condition of athlete archives held by athletes.

-

Make recommendations about ways to integrate historically excluded athletes' memories into the post-apartheid collection.

Literature review

Policy and legislative frameworks are important in the building of inclusive archival holdings. Since the inception of archives, legislative frameworks have always been in place to control the incoming valuable archives. However, some scholars lament that these legislative frameworks have not proven to be effective in capturing the essence of the whole community and instead focus only on a few elites. For example, Harris (1996) argues that in South Africa:

[T]he apartheid regime was content with destroying all oppositional memory and used policies such as censorship, confiscation, banning, incarceration, assassination, and a range of other oppressive tools to achieve this. (p. 8)

In South Africa today, there are pieces of legislation that attempt to reverse apartheid policies by collecting what is called 'non-public records' because of the need to document aspects of the neglect of the province by archival repositories in the past. The collection of such records came about with the promulgation of the NARSSA Act and the provincial archival legislation that mandate the national and provincial archives services with the responsibility to collect non-public records (South African Government 1996). In terms of the NARSSA Act and provincial archival legislation, public archival institutions have a responsibility to collect non-public records with enduring value of national and provincial significance which cannot be more appropriately preserved by another institution. In section 3 of the NARSSA Act, it is captured as 'The objects and functions of the National Archives' (Archival Platform 2015). Explicit in this mandate is the acknowledgment that the inclusion of 'non-public records' is not mandatory. What is crucial, however, is the implementation of this provision in the legislation as it encourages the transformation of archival holdings by including the voices of the voiceless in the repositories. The inclusion of non-public records in the 1996 Archives Act and the provincial archival legislation marks a clear departure from previous acts such as the 1922 Archival Act which allowed chief archivists to acquire non-public records and documents deemed necessary, or the 1953 Act which similarly made provision for the acquisition of material of historical value not forming part of the public archives. The present provision of inclusion of non-public records is aimed specifically at redressing and transformation. In this regard, issues of historical bias and exclusion are addressed.

While legislation makes provision for non-public records, athletics stories and memories are often neglected and forgotten. In his chronicle, Runaway Comrades De la Motte (2014) laments the forgotten South African leading black ultra-marathon runners in the era from 1974 to 1990. For example, De la Motte (2014) cites Hosea Tjale who left a breath-taking record of running achievements, but who has been forgotten and forsaken since he retired quietly on 31 May 1993. After he completed his 13th Comrades Marathon, he left quietly without an exit interview, farewell or announcement from the media, as if he was an ordinary runner. He has since retired to a rural area in the Limpopo province and his memories have been forgotten. Ngoepe (2020) identifies another sad story like the one of Vincent Rakabaela from Lesotho whose death went unnoticed. His unmarked grave was found in 2009 only to find out he had died in 2003. Vincent Rakabaela was the first black person to win the Two Oceans Marathon and the first black person to win a gold medal in the Comrades Marathon in 1976. These are just a few examples of forgotten sports heroes. There are others such as Titus Mamabolo, David Tsebe and Ramie Tsebe, to mention just a few, who are not included in archives. Even writers rarely document stories about runners. The athletics sports code can be the starting point to close the gap that has existed for a long time. This sports code appeals to many people in South Africa, amateurs and professionals alike.

Review of the literature also indicates that sports archives in developed countries such as Australia and the United Kingdom have increased over the past few decades. While many sports archives have been destroyed or damaged by neglect, several private collectors have diligently built up fine collections that have become the core of public collections. Record-keeping in sports is in such a bad state to the extent that it is non-existent, especially among smaller clubs (Cashman 2001). Ngoepe (2020) observed similar patterns in South Africa where records of the FIFA 2010 World Cup, 1999 All Africa Games, and the 1995 Rugby World Cup, to mention just a few major events, are fragmented and not easily accessible by the ordinary person. These gaps and omissions in archives are a real problem for sports historians (Booth 2006). Sjoblom (2009) also observed similar patterns in New Zealand and affirms that there is often minimal recognition of the value of sports documents. As such, where sporting materials are deposited into an archive, there is no well-structured plan to determine what is worth preserving. Fagan (1992) laments that one problem with the collection of personal papers, especially concerning sport, is that it is often only the papers of the famous or successful that will be collected. Cacceta (2015) concurs that there is a big gap in the information of ordinary road-running champions. Indeed, most memories of ordinary road-running champions are found nowhere close to the mainstream archives. The only publication they fully feature in is when something scandalous happens, such as when Caster Semenya, a South African middle-distance runner and winner of two Olympic gold medals and three World Championships in the women's 800 m, was denied the opportunity to compete multiple times because of her being transgender; Oscar Pistorius, a Paralympian, who was arrested after killing his girlfriend, Reeva Steenkamp; or when Ludwick Mamabolo, a 2012 Comrades Marathon winner, was once accused of doping with methylhexanamine, which is found in products for nasal decongestion (Ngoepe 2020).

Research methodology

This qualitative study adopted an oral history research design to collect data on the inclusion of athletics memories in archival systems. Oral testimony and oral tradition were used as data collection tools. Snowball sampling was used to help locate historically marginalised athletics heroes. In this study, nine participants were interviewed as reflected in Table 1. Data saturation in this kind of study is unreachable as every participant has their own story to tell. However, in some instances, there were common threads from the responses. Non-saturation of information could arise from 'silences' (Kamp et al. 2018:77). One of the causes of silences is specific missing information in society as a result of information censorship or because it would be regarded as taboo to write about a particular phenomenon or historical omission and censorship (Kamp et al. 2018). Because of the outbreak of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, most of the participants preferred a telephonic interview, although some requested a face-to-face interview. Interviews were conducted using English as the medium of communication and in some instances Sepedi and isiZulu. As the aim of the study is aligned to preserving the memories of the unsung running heroes, there was no need to hide the identities of athletes, except for some participants who provided oral tradition for athletes that the researchers were unable to trace. While some were departed, others could not be traced. In all the interviews, permission was granted to record the conversations and the athletes' names to be publicised. The audio records of responses provided responses and opinions of the participants. All participants were informed of this and gave oral consent before the interview. The low-risk ethical clearance application was reviewed and approved by the Department of Information Science Research Ethics in line with the University of South Africa's Policy on Research Ethics and the Standard Operating Procedures on Research Risk Assessment, also approving participants' names to be publicised as the study gives recognition to the historical unsung athletes. Data collected were corroborated with information from old newspaper cuttings from the South African Media database. Furthermore, the researchers also visited the Comrades Marathon House in Pietermaritzburg. During the interviews, the researchers took pictures of medals, trophies and other memorabilia with the permission of the participants. Other pictures were provided by the participants themselves. As reflected in Table 1, the researchers obtained the names of the athlete participants and their gender, and it was established that there were more men than women. This shows that men have always been on a more advantageous side of running in South Africa than women; hence, the low number of women as compared to black men in athletics. Sikes and Bale (2014) also observed that sports organisations in South Africa treated women as add-ons, which resulted in most female sports heroes being marginalised.

Results and findings

Data were analysed as per the objectives of the study and the quotations were presented verbatim.

Memories of athletes excluded in archival holdings

This objective sought to describe memories of athletes excluded from archival holdings. For many decades before democratisation in 1994, the potential and talent of black athletes in the country have been largely neglected and manipulated for political reasons (Labuschagne 2016). Hence, Lane (1999) questions the whereabouts of young runners who used to dominate road running during those dark days in South Africa. Ghaddar and Caswell (2019) feel strongly that nothing positive about what black athletes did was reported with any prominence.

Roots of athletes' running careers

This section sought to identify why athletes started running. The findings revealed that the reasons why participants started to run differ almost from one athlete to another. However, the common thread is that basic schools gave many novice runners a platform to start. Running was one of the sports codes that pupils had to do as part of the curriculum. Basic education included sports codes such as athletics in its curriculum from as early as 1948. For example, every Wednesday pupils in black schools practised various sports codes in preparation for competitions with other black schools because interracial competitions were prohibited by the apartheid laws (Lion-Cachet 1997). For example, Rosina Sedibane explained that:

'I started running during foundation phase, then called primary school. Even though I was not competing until high school. My running career was sported when I was a pupil at Hoffmeier High School in 1974 at Atteridgeville, Pretoria, where I grew up.'

For male athletes, it became apparent that soccer had always been parallel to their running. Although soccer was rife in rural areas, opportunities to become professional soccer players were very scarce or non-existent. Hence, in The Memoirs of a Comrades Champion, Ngoepe (2020) reckons that Ludwick Mamabolo aspired to be a professional soccer player but ended up being a professional elite ultra-marathon runner. Similarly, Titus Mamabolo explained that:

'I started running in standard 6 in Ga-Molepo, although I did not take it seriously as I was more into soccer. I then moved to Pretoria to look for a job and started taking the sport a little more seriously. My first official race was in 1963 at Mamelodi and I came in position two with one session of training. I remember joining the team one weekend for this one-mile race and was outran by Edward Setshedi. When I told him about my one-day preparation for the race, he told me that is not training. Everyone was so surprised at how well I performed. After that, I represented Northern Transvaal in Welkom and did quite well. I was just doing it for fun, but Edward said I should train harder; and the rest is history, as I was able to tour several countries before having an intermittence between 1975 to 1985. When I came back, I was also able to smash the masters' record in a standard marathon which is still standing today. As a master, I also came position 2 in City2City 50 km marathon.'

Although most athletes developed a love of running from basic education, some athletes started to run professionally after their arrival in Gauteng in search of work, usually at the mines or just doing odd jobs such as gardening. The following participants started to run after standard 10 because running proved to be worthwhile. For example, Johannes Kekana explained that:

'I started running shortly after finishing my standard 10 [Grade 12]. I went to Gauteng in search of work, as I could not afford tertiary fees. There I got a job but left it in 1997 to focus on running as a career. I had no formal tertiary education. As such, what I did was just odds jobs and during those times there was no work, and I had no money to go tertiary. Running was my only hope to be like other people.'

The same sentiment was also shared by Enoch Skosana, who explained:

'I started running from the age of 14 in 1988-89, but, professionally, I started running in 1991. I started with judo. But I left judo to run after finishing my high school because I needed something with value, and that was running.'

Merrett (2004) suggests that the mining companies provided tracks and coaching, and every major gold mine reportedly had an international standard track by the mid-1960s. Indeed, several runners who have won major international marathons were products of the mines. For example, to help his fellow athletes to qualify for international races, one participant had to join the mines for advanced training and equipment. In this regard, Joseph Leserwane explained that:

'I started running at the mines in 1964 with a sole purpose of helping my fellow black runners, Humphrey Kgosi and Benoni Malaka to qualify for 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games.'

For Rosina Sedibane, the love of running was solely to prove the running capabilities of black athletes, especially women, as against the oppressing apartheid laws and the whole world. In a similar vein, James Mokoka noted:

'The love for running emanates from schools of Mokomene in Botlokwa. From there, I went to teach at a primary school at Soweto called Taupedi where I formed a club called Soweto Hurtze. This club was made of various talented kids selected from interschool competitions who were running from 400 m above. That was because during apartheid, black women could only run 100 m and 200 m. Apparently, according to whites, black women had no capacity of running above that. I trained these primary young athletes to run 400 m races and above to prove that, actually black women have that capability. I then left teaching to become a Johannesburg sports organiser and a full-time coach. I even took a course in sports. During one of the running competitions I hosted, I invited these two white guys by the names of Paul Nesh and Pieter Rich to Orlando Stadium where black runners were competing, to inspire my runners. I wanted my runners to see top runners in Springbok colours as they were not allowed to even see whites competing. When Sunday newspaper came out, I was crucified, being questioned as to what authority do I have to make blacks and white to compete together. That was during South African dark days. That's how my love for running emanated.'

For other participants, running emanated as a solution to their health problems. For example, Margarete Sedibane stated:

'My love for running started in 1973 at primary school until high school, and I would come position 2 or 3. I had a bronchitis problem, which meant I had to see doctors every now and then. But after I began running I would feel better but eventually was healed. I also had to push my sister, Rosina, to be competitive by training with her.'

Running influence

This study revealed that multiple factors influenced the participants to start running, including family or friends who also performed well in running. Moreover, for some athletes, the influence was just by fate. This is also emphasised by Ngoepe (2020) in the biography of Ludwick Mamabolo that the athlete started jogging after an injury he incurred in a soccer match. One day while jogging, wearing soccer boots, he met a runner who invited him to a time trial.

For example, these participants, who are siblings (Rosina and Margarete Sedibane) concurred with the latter assertion by alluding that:

'All this influence emanated from our family. Running runs in our family. Our mother used to be the best in all indigenous games played during those times, running even faster than boys, my father would bring reminisces time to time of how my mother used to outrun boys. That really made me feel like I am on the right path.'

The same sentiment was also shared by Titus Mamabolo, who explained:

'The influence of running comes from my family which always excelled in all indigenous games. My uncles at traditional initiation school used to outrun everyone. Running runs through our blood.'

While these athletes were influenced by their friends, Linda Hlophe explained that:

'Instead of working at the mines after high school, I proceeded with my studies and met Mr Kelepe who was the fastest runner during those times. He is the one who influenced my running greatly. I also met famous runners like Shadrack Hoff. The community of Mamelodi also used to praise me as I train on the street, gave me huge support. I was always the talk of the community. Even taxi drivers would hoot when they pass me. Even after I got a job as correctional senior officer, I would run from work to home to work.'

But soon running became a career. These two participants started seeing value in running and then never stopped. For example, Enoch Skosana mentioned that:

'What influenced my running was my brother. My brother and I used to compete at home. Every time my brother would bring medals and prizes. Yet I brought only medals. I got influenced to run so that I also get a prize after winning. I realised as I grow up, medals won't help me much, I needed something with value and that was running.'

Similarly, Johannes Kekana shared the same sentiment:

'A friend of mine influenced me to run by showing me how much they are getting from running. This guy, John Tjale from Mokopane, is the one who always motivated me by helping me to join the Randmeester Athletic Club he was running for in Pretoria. I then took running as a career.'

For Joseph Leserwane and James Mokoka, the influence has always been political. For example, in his own words, Joseph Leserwane said:

'I saw Daily Run Mail newspaper where two running records from whites and blacks competing to be allowed to qualify for Tokyo Olympic Games. Humphrey Kgosi, also known as The Ghost and Benoni Malaka ran 1 min 45 sec. These two needed a support from lot of fellow blacks' runners because they were in a war. To help these guys, I joined a gold mine, a stone thrown away from Klerksdorp where I was training to qualify to help these guys.'

While James Mokoka explained that:

'The influence came from a need to ensure that black women athletes are as good as everyone.'

Athletes' running achievements

The study findings revealed that most runners never received anything from the races they took part in, except medals and trophies. In 1995, even in big races like the Comrades Marathon, black runners were offered zero awards, even after winning, but many rose to the top regardless of this (De la Motte 2014). Some participants have gone as far as international competitions, some were awarded Springbok colours, while some are record holders of multiple races and others have proven to the apartheid regime and the whole world their capability in running, regardless of their skin colour and gender.

For example, Rosina Sedibane explained that:

'Under the leadership of Coach James Mokoka, I managed to become the first black women to be awarded Springbok colours. That is only because I managed to be field record holder of 400 m in (47 sec), 800 m (2 min 7 sec), 1500 m (4 min 25 sec) and 3000 m (11 min 4 sec) under the strains of apartheid. And it could have been better with better facilities and coaching. Because of my unavoidable record of being the fastest black woman on the track, I got an invitation to compete at a white-only competition at the University of Port Elizabeth alongside Aneen de Jager. That was until the knee ailment I got in 1978 started troubling me and I had to retire from running. In 2002, they named the sports academy after me, the Rosina Sedibane Modiba Sports School of focused learning, situated in Laudium. I was also honoured with a book titled A Dream Denied by Lorato Trok. The book entails my running journey from the beginning until recently.'

In addition, Titus Mamabolo indicated that:

'I was the first South African to be invited to Brazil to represent South Africa during the apartheid era even when the country had no relationship with Brazil because of apartheid policies. But I went because South Africa's government influenced me to go there and participate with the hope that apartheid would end. To my surprise, I became the first South African to obtain position one in Brazil with my first attempt. I managed to be the first South African to be invited to London to receive an award for outrunning a white person during the apartheid era. I am the second black South African to receive Springbok colours blazer for athletics while not just anybody, including whites, would receive such an award. When you receive such a blazer, it meant you deserved it. I was in the third position in a City-to-City Marathon while in the age of 52. I also established athletic club known as MEMO athletics club in collaboration with Jorge Mehale based in Polokwane so that I can train kids and expose them to opportunities we never had when we started running.'

In response to the lack of monetary rewards for these athletes for running domestically, most of the top runners seized opportunities to compete overseas where monetary rewards were better (Lane 1999). The best example obtained through oral tradition is that of Albert Moholwa, who originally hailed from Moletji in Limpopo, but was a resident of Mamelodi. The researchers struggled to get hold of him but through oral tradition, it was discovered that Moholwa won several races, including the Windhoek marathon in 1988 where he was transported with a helicopter. As his winning prize he received six glasses which urban legend says broke on-board while commuting using a train to Mamelodi Township. For another race, his winning prize was a bag of oranges, which he shared with fellow commuters on the train. The bag was finished before the train reached Eerste Fabrieke Train Station in Mamelodi, which is about 25 km from Pretoria station. Among the races he won were the Pick n Pay and the Wally Hayward marathons. Moholwa disappeared from the athletics scene and his achievements, like those of other great athletes, have been forgotten. Most people do not know about him and his memories would soon be forgotten. Stories like this need to be recorded for future generations. For some athletes, running achievements included being able to give back to children, so that these children would be exposed to running opportunities they never had in the initial stages of their running careers.

For example, Enoch Skosana explained that:

'I saw Skosana Development Club as a way to give back to young kids. My club offers runners scholarships to run while studying because things have changed now as compared to then when sponsors would approach you after winning a big race. Now you have to apply. I also won a floating trophy. The floating trophy that I once won, now clubs compete for it every year during Skosana Marathon held annually.'

On the other hand, even when it was clearly explained that no mixed sport would be permitted at the club, provincial or national trial level and that the Springbok emblem as part of athletes' achievements was reserved for the white athletes (Merrett 2004), there are some black athletes who still received it. When asked what they have achieved, Joseph Leserwane explained that:

'Actually, athletics never benefited me as black elite runner. The reward I ever got from athletics was the money I got from athletics in 2016, valued R10 000 and a blazer that was delayed for about 10 years. They would book us expensive accommodation and food but without no prize after winning. I ran in Milan, Italy. I then qualified for Springbok colour jersey which was issued 10 years later in 1978. The delay was attributed to nothing else but my colour of skin. Mathews Batswadi qualified for his Springbok jersey 1977 after me, followed by Titus Mamabolo and Obert Serakwane. In 1972, I trained very hard to qualify for Mexico Olympic Games, which I did, but I was denied competing because of colour of my skin again. In 1973 around June, just after the Olympic games, there was a white guy, Danie Malan, running middle distance: 800 m, 1500 m and 3000 m. He begged me to help him to break 1000 m world record in Munich. We went to Swaziland and stayed there for two weeks training. The plan was to run every 200 m of 1000 m in 26 seconds to break the world record. I took it upon myself to become the pacemaker, running 26 seconds per each 200 m. So, he just sticks to my bat. After 600 m, I opened for him and he made it.

Actually, just after my arrival at Jan Smuts International Airport, now called OR Tambo International Airport, from the same race where we broke the 1000 m world record, I met up with two white police officers who took my passport and said you are starting to be too white now, in Afrikaans. That was because I helped a white guy break the world 1000 m track record and that I used the spotlight to speak as I like. While I was still into running, I stopped. I did not see the need to run anymore. Apartheid killed my motivation. I will train hard to qualify for Olympics but when I qualify, they deny me to go. Nevertheless, my achievement includes becoming a coach, producing about four Springbok colour holders such as Obert Serakwane from North West, followed by Matthews Batswadi, Rosina Sedibane and Margarete Sedibane.'

Athletes' archival memory location, custody, volume and condition

This objective sought to determine the location, custody, and condition of archival memories of athletes. There is now a greater sense of the value of records and archives in sport, the growth of sports exhibitions, the rise of sports history and sports studies, the recognition of the value of knowledge transfer, and the fact that memorabilia have become big business. To better address this research objective, participants were asked to elaborate on where most of their memories are kept and what the condition was of the memories kept. In some instances, memories in the form of pictures, newspaper cuttings, trophies, medals and Springbok blazers were displayed.

Location of athletes' memories

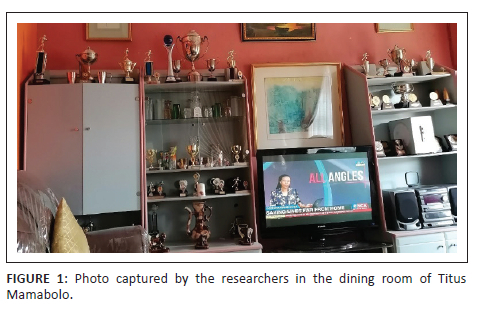

As reflected in Figure 1, the dining room of the legendary Titus Mamabolo has been turned into a museum with the trophies and medals he won over the years. His collection ranges from old newspaper clippings about him and other athletes such as the 1960s New Transvaal light heavyweight champion, James Mathato, from Tembisa; newspaper clippings of countries he has competed in; radio interviews; questions and answers on separate papers; and pictures of historical legendary runners he competed against, including the legendary Lawrence Peu, Xolile Yawa, David Tsebe, William Mtolo, Alfred Sepirwa and Mathews Temane.

Cashman (1988) argues that sports history has suffered because there is a lack of sports memory materials available. In trying to assess the current situation, it has proven quite difficult to determine which institutions, if any, hold sports material. The study established that athletes have archival memories with them. For example, Rosina Sedibane said that:

'I have medals, trophies, certificates from high school, certificates of awards, trophies, and pictures here with me in my house. I also have a lot of newspaper clipping from newspapers that used to publish our results after every competition just to keep a record of those bombastic words used to regard my performance.'

The same sentiment was shared by Margarete Sedibane who explained that:

'Most of my memories are medals and trophies. As for certificates, I hardly keep those because they are old. Certificates which I have are from races I used to run in high school.'

The above statement is also supported by Bale (1998), who concurs that amid other locations where these athletes' memories are located, these records remain with the athletes themselves, except at local government, school archives, university archives, government records and holdings in film and sound archives.

As indicated on Linda Hlophe's display in Figure 2, some of the collections that these athletes possess are stored in their houses. Enoch Skosana and Johannes Kekana concurred that the medals, trophies, certificates and pictures are stored in their houses. It is worth noting that the researchers were unable to visit their homes as they did with other participants such as Titus Mamabolo.

In contrast, of all the memories that the elite athletes normally have, Joseph Leserwane had only a Springbok jacket at his home as reflected in Figure 3. Joseph indicated that most of the memories are stored in his head and can be passed through oral tradition as he was doing during the interviews. He indicated that:

'I know it will be hard to believe, but I hated memories such as medals, certificates and trophies. All I wanted was just to qualify to run. All I have here in my house is my delayed Springbok colours jersey. I have two now since the first one became so small and they gave me the second one.'

Conditions of memories

This question was meant to solicit information from athletes about the condition of the memories they kept. Most participants elaborated that most of these memories are just displayed in their living rooms. There are certificates on the walls, trophies and medals on the TV stands and photos just stored away safely. For example, Titus Mamabolo explained that:

'Most of my medals are in boxes, you can't even pick the box up. While some medals I decorate with them in the house, as you can see. I also have prestigious trophies that are displayed on my TV stand and here in the dining room.'

Similarly, Enoch Skosana explained that:

'Medals are displayed in my house; some are in the bags. Others I give to my runners after competing. With others, I am just decorating with them. But the floating trophy, clubs are competing for it every year.'

The statements of the aforesaid participants were silenced arising from specific missing information in society, which could be because it is taboo to write about a particular phenomenon or historical omission and censorship (Kamp et al. 2018); the same by Rosina Sedibane who indicated that her memories are mostly displayed in her living room as reflected in Figure 4.

Participants emphasised that with their memories, their houses have turned into home museums. For example, this is emphasised by Johannes Kekana when explaining that:

'With memories I have, I just decorated with them in my house. As for trophies, my house is like a museum. There are trophies displayed on my sitting and dining room both in my houses here in Mpumalanga, Gauteng and Limpopo. There are so many medals are just full in a bag.'

Although some of these athletes turned their houses into museums, one participant said that he just donated some of his memories to his loved ones. Linda Hlophe explained further that:

'Most of the medals and trophies are displayed in my house. Yet, some I normally donate to my family and people who mean much to me, to remember me with. Certificates which I received the time I was still at high school also are just stacked in a store room.'

Most of the runners from 1960 had so much to display in terms of running memories they have accumulated through their running careers. Joseph Leserwane sadly explained that the only memory he has is in his wardrobe, that is, his late arrival Springbok jersey. He indicated that he relied mostly on oral history and his mind to remember things as he says:

'No one can take away that from me. However, I can further share the memories if one wants to document a book about me.'

Integration of historically excluded athletes' memories into the archival holdings

This objective sought to recommend ways to integrate historically excluded athletes' memories into the archival holdings. There is now a greater sense of the value of records and legacy in general, the growth of sports exhibitions, the rise of sports history and sports studies, the recognition of the value of knowledge transfer and the fact that memorabilia have become big business. However, the value of sports records like in Australia has not been fully appreciated (Cashman 2000).

Despite these odds, many distance runners found ways to compete against the best in the world. However, their achievements were not recognised by any sport federation outside of the country. Furthermore, these distance runners were never given enough recognition in South Africa either. To redress the past, the researchers asked the participants what they would like to be remembered for. According to Cook (2000), by capturing memories in the archives, the archives will memorise and legitimise societies' identity and thereby influence the future by shaping the past. While others fought apartheid laws through running, like De la Motte (2014) suggests, some athletes rose to the pinnacle regardless of many prohibiting apartheid factors. For example, this participant (Titus Mamabolo) concurred with the latter statement by stating that:

'I would like to be remembered as a man who competed with whites during South Africa's dark days and won against all odds. I would like to be remembered as the pathfinder. I would like to be remembered as a hero who represented the country even on international level when everyone was pulled back by apartheid policies. I would also like to be remembered as a man who used his fitness to fight oppression as compared to violence.'

James Mokoka suggested that his memory should be attached to opening doors for the marginalised, especially black women. He indicated that:

'I would like to be remembered as a man who proved to the world that black women are as good as everyone in athletics. Because there was a myth that black women athletes are not good as other people and I am glad I managed to do that through Rosina and Margarete Sedibane who are now great mothers. So that saying "black women cannot run because they will have muscular bodies or won't conceive" is no more because I proved them wrong. I also want to be remembered as a black coach who broke the barrier of successive whites' sports coaches in South Africa and I also believe God has kept me until this day so that I can tell stories of those who can't narrate for themselves.'

Similarly, Rosina Sedibane explained that:

'I would like to be remembered as the first black women who opened doors to other black women in running fraternity. A woman who, through the passion of running, broke the barriers of racial segregation and gender inequality in South Africa.'

In contrast, one participant felt that apartheid did more harm to him than good because the only memory he can recall about running is a blue Springbok blazer which he received late. In this regard, Joseph Leserwane explained that:

'I want to be remembered as the first black man to receive Springbok colours although I received the jersey 10 years after it was awarded.'

Three participants (Linda Hlophe, Enoch Skosana and Johannes Kekana) said it is through running that they found a career, and with that career, they wanted to be remembered as servants of the people that touched the lives of many people. They said that they would like to be remembered for what they did for children - how they promoted children and gave them opportunities they never had when they started running. They feel the recognition when parents give them compliments after they see their children's changed behaviour shortly after meeting these latter two athletes.

Donation of athletes' running memories

Archival collection policy makes provision for the acceptance of donations of archives in the repositories. This question sought to identify whether the participating athletes would donate some or all of their memories so that there could be an integration of historically excluded athletes' memories into the archival holdings and thus contribute towards the decolonisation of archives. All participants declared that they do not mind donating some or all of their memories, as it will be a valuable treasure that could be accessed by everyone. The participants indicated that they are willing to make these donations as long as government archives repositories would care for these memories well and make them accessible to the wider public. For example, when asked if it would be possible to donate some or all of her memories, Rosina Sedibane said:

'Yes, I do not mind donating some of my memories. But as for print ones, please do copies for me and take the originals. The original paper, as time goes by, loses life and the content becomes blurry.'

Similarly, Linda Hlophe explained that:

'Why not? I cannot say, yes, this is not for me. This is a footprint I would love to leave for my beloved South Africa to remember me by. To see that footprint and say, "Wow, we want to meet this person.'' So, I do not mind donating some of my memories for I am overwhelmed with these memories.'

Titus Mamabolo raised a concern that if original memories are donated to archives, what will he be left with? Rather, he said:

'Yes, I do not mind donating, but it would be better if you do copies of originals I have.

That is so I can remain with originals for future references. Concerning the trophies and medals, perhaps a museum or archives can have a display for such. 'When I am no longer relevant, my descendants can inherit them back. That is, terms and conditions that I can put for such donation.'

Conclusion and recommendations

This study concludes that awards ceremony certificates, trophies, winning medals, Springbok jackets, newspaper clippings and pictures as memories of the running careers of these athletes are housed by themselves. Athletes' houses have been transformed into museums containing all their running memories displayed all over their living rooms. To that effect, should these athletes' memories remain unaccounted for, they will all also be lost or inaccessible like those literature speaks about, that it will be difficult to even locate them or know who or what institution possesses them. The study establishes that one of the ways to include historically excluded athletes' memories in the post-1994 collection could be by donating some, if not all, of their running memories by collecting these athletes' memories into archives repositories and museums. It is through these memories that athletes' footprints will be left behind. People from all over the world would see these memories later after the athletes have departed and find out what they were all about.

It was clear from the interviews that there is a need for the use of oral memories to build inclusive archive through the collection of athletics memories. Oral history has proven to be efficient in bringing life to the voices of the heroes that have been marginalised for so long as it deals with memories transmitted over many generations. Hence, today's archivists work to increase instances of previously unrepresented and underrepresented people once silenced from the historical record to build inclusive archives through methods such as oral history.

It is clear from the study that at the individual, family or community level, records, library materials and artefacts are preserved together hence it is established that the athletes' memories included certificates, trophies, medals, Springbok jerseys, newspaper clippings and pictures. While it is acknowledged that athletes' memories as private or family archives can stand independently without playing subservience to the conventional archives, such memories in the form of records and objects are vulnerable to loss in the households of individuals as they are not properly preserved. The study suggests that to be aware and have a clear picture of the location and condition of athletes' memories, there must be an inventory that is central and contains addresses of the location of athletes' memories. Alternatively, athletes can be trained to better handle their running memories to ensure their safe preservation. In addition, sports federations can be capacitated to preserve memories of athletes through museums that double as archives as at the community and individual level memories are often preserved in archival, object and artefacts form. Until these sports archives and objects are considered as an important history of a unique element of South Africa, in which the people have run together in the same direction, it will forever be lost.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the participants of this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

Both authors contributed to the design and implementation of the research, the analysis of the results and the writing of the article.

Ethical considerations

The low-risk ethical clearance application was reviewed and approved by the Department of Information Science Research Ethics in line with the University of South Africa's Policy on Research Ethics and the standard operating procedures on research risk assesment, also approving participants' names and photos to be published as the study also gives recognition to the historical unsung athletes - 2020-DIS-0014.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

References

Alegi, P. & Bolsmann, C., 2010, 'South Africa and the global game: Introduction', Soccer & Society 11(1-2), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970903331284 [ Links ]

Archival Platform, 2015, State of the archives: An analysis of South Africa's national archival system, University of Cape Town, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Bale, B., 1998, 'The African body? Visual images and "imaginative sports"', Journal of Sport History 25(2), 234-251. [ Links ]

Booth, D., 2006, 'Sites of truth or metaphors of power? Refiguring the archives', Sport in History 26(1), 91-109. https://doi.org/10.1080/17460260600661273 [ Links ]

Cacceta, W., 2015, Bob de La Motte: Blood, sweat and arrears, viewed 10 September 2021, from https://www.perthnow.com.au/news/wa/bob-de-la-motte-blood-sweat-and-arrears-ng-affc3d169dfb87d34e4a786be04b62c7. [ Links ]

Cameron-Dow, J., 2011, Comrades marathon: The ultimate human race, Penguin Books, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Cashman, R., 1988, 'Illustrating sports history', Sporting Traditions 4(2), 239. [ Links ]

Cashman, R., 2000, 'Olympic scholars and Olympic records: access and management of the records of an Olympic Games', Fifth International Symposium for Olympic Research 12, 207-214. [ Links ]

Cashman, R., 2001, 'Sports archives in Australia', Archives and Manuscript 29(2), 82. [ Links ]

Cook, T., 2000, 'Remembering the future: Appraisal of records and the role of archives in constructing social memory', in F.X. Blouin Jr & W.G. Rosenberg (eds.), Archives, documentation and institutions of social memory. Essays from the Sawyer seminar, pp. 169-181, University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI. [ Links ]

De la Motte, B., 2014, Runway comrade, Quickfox Publishing, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Derrida, J. & Prenowitz, E., 1995, 'Archive fever: A Freudian impression', The Johns Hopkins University Press 25(2), 9-63. https://doi.org/10.2307/465144 [ Links ]

Fagan, R., 1992, 'Acquisition and appraisal of sports archives', ASSH Bulletin 16, 193-225. [ Links ]

Ghaddar, J.J. & Caswell, M., 2019, 'To go beyond: Towards a DE colonial archival praxis', Archival Science 19(2), 71-85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-019-09311-1 [ Links ]

Harris, V., 1996, 'Redefining archives in South Africa: Public archives and society in transition, 1990-1996', Archivaria 42, 6-27. [ Links ]

Harris, V., 2001, 'Seeing (in) blindness: South Africa, archives and passion for justice', Archifacts 72(2), 1-13. [ Links ]

Harris, V., 2014, 'Twenty years of post-apartheid archiving: Have we reckoned with the past, or has the past reckoned with us?', Journal of the South African Society of Archivists 47, 89-93. [ Links ]

Jimerson, R.C., 2007, 'Archives for all: Professional responsibility and social justice', The American Archivist 70(2), 252-281. https://doi.org/10.17723/aarc.70.2.5n20760751v643m7 [ Links ]

Kamp, J., Legêne, S., Van Rossum, M. & Rümke, S., 2018, Writing history! A companion for historians, Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam. [ Links ]

Ketelaar, K., 1992, 'The European community and its archives', The American Archivist 55(1), 40-45. https://doi.org/10.17723/aarc.55.1.504782446h23750x [ Links ]

Labuschagne, P., 2016, 'Sport, politics and black athletics in South Africa during the apartheid era: A political-sociological perspective', Journal for Contemporary History 41(2), 82-104. https://doi.org/10.18820/24150509/JCH41.v2.5 [ Links ]

Lane, A.A., 1999, 'South African distance runners: Issues involving their international carriers during and after apartheid', Master's dissertation, Eastern Illinois University. [ Links ]

Lion-Cachet, S., 1997, 'Physical education and school sport within the post-apartheid educational dispensation of South Africa', PhD thesis, University of South Africa. [ Links ]

Merrett, C., 2004, 'From the outside lane: Issues of "race" in South African athletics in the twentieth century', Patterns of Prejudice 38(3), 233-251. https://doi.org/10.1080/0031322042000250448 [ Links ]

Ngoepe, M., 2019, 'Archives without archives: A window of opportunity to build an inclusive archive in South Africa', Journal of South African Society of Archivists 52, 149-166. [ Links ]

Ngoepe, M., 2020, Stir the dust: Memoirs of a comrade champion, Ludwick Mamabolo, MakHERP Publishers, Polokwane. [ Links ]

Rodrigues, A., 2013, 'Portuguese community-based organisational records: A comprehensive archival collecting framework', Innovation: Journal of Appropriate Librarianship and Information Work in Southern Africa 54, 48-66. [ Links ]

Sikes, M. & Bale, J., 2014, 'Introduction: Women's sport and gender in sub-Saharan Africa', Sport in Society 17(4), 449-465. [ Links ]

Sjoblom, K., 2009, 'Sports archives internationally - A development with risks and challenges?', in L.T. Smith (ed.), Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous people, Zed, Dunedin. [ Links ]

Tassiopoulosa, D. & Haydam, N., 2008, 'Golf tourists in South Africa: A demand-side study of a niche market in sports tourism', Tourism Management 29(5), 870-882. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2007.10.005 [ Links ]

Venter, G.B., 2016, 'Gone and almost forgotten? The dynamics of professional white football in South Africa: 1959-1990', PhD thesis, University of Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Wetli, A., 2019, 'Promoting inclusivity in the archive: A literature review reassessing tradition through theory and practice', School of Information Student Research Journal 8(2), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.31979/2575-2499.080204 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Mpho Ngoepe

ngoepms@unisa.ac.za

Received: 09 Mar. 2022

Accepted: 06 Aug. 2022

Published: 10 Oct. 2022

Note: Special Collection: Social Memory Studies, sub-edited by Christina Landman (University of South Africa) and Sekgothe Mokgoatšana (University of Limpopo).

1 . The Two Oceans Marathon is a 56 km/35-mile ultramarathon held annually in Cape Town, South Africa on the Saturday of the Easter weekend since 1970 (Cameron-Dow 2011).

2 . The Comrades Marathon is an ultra-marathon of a distance ranging from 87 km to 90 km which is run annually in the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa between the cities of Durban and Pietermaritzburg. The direction of the race alternates each year between the 'up' run (87 km) starting from Durban and the 'down' run (90 km) starting from Pietermaritzburg (Cameron-Dow 2011).