Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

HTS Theological Studies

On-line version ISSN 2072-8050

Print version ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.78 n.1 Pretoria 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v78i1.7882

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

An alleged homily on the paralytic by John Chrysostom in the codex Athonensis, Lauras A 112 (Eustratiadis 112)

Radu GârbaceaI, II

IFaculty of Orthodox Theology, Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu, Sibiu, Romania

IIDepartment of Systematic and Historical Theology, Faculty of Theology and Religion, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Through the efforts of the Institut de Recherche et d'Histoire des Textes (IRHT), a list of manuscripts is available that preserves homilies on the healing of the paralytic. Included in this list is the codex Athonensis, Lauras A 112 (Eustratiadis 112), which, according to those who provided its second description, preserves in the last four folios 'a homily on the paralytic by John Chrysostom'. After a brief presentation of what is known about this codex, this article offers a detailed examination of the codex's last four folios, revealing that the description of them by Spyridon Lauriotis and Sophronios Eustratiadis is inaccurate.

CONTRIBUTION: This article provides the first thorough examination of the last four folios of the codex Athonensis, Lauras A 112 (Eustratiadis 112), demonstrating that they do not contain 'a homily on the paralytic by John Chrysostom' but rather several fragments of homilies on Thomas, Mid-Pentecost and the Ascension. Thus, the article contributes to the description of the codex and to the identification of a previously unknown manuscript witness to several homilies.

Keywords: Athonensis, Lauras A 112 (Eustratiadis 112); the healing of the paralytic; John Chrysostom; Proclus of Constantinople; Leontius, presbyter of Constantinople; Pseudo-Chrysostom.

Introduction

While consulting the Pinakes database managed by the Institut de Recherche et d'Histoire des Textes (IRHT) in preparation for an edition of two unedited homilies on the paralytic (CPG 4978 and CPG 5055),1 the author of the present article noticed the presence of Athonensis, Lauras A 112 (Eustratiadis 112) in the list of manuscripts preserving patristic homilies on the theme 'Paralyticus'.2 In compiling this list, the members of the Pinakes management team relied on existing catalogues and inventories, some of which date from the late 19th or early 20th centuries, without being able to conduct a verification in each case. It is therefore necessary to re-examine the manuscripts listed in order to ascertain whether 'Paralyticus' refers to known texts or unknown texts, or whether there is any connection between the texts bearing this label.

The present article, then, checks the brief description given by the editors of the Catalogue of the Greek Manuscripts in the Library of the Laura on Mount Athos regarding the last four folios of the manuscript Athonensis, Lauras A 112 (Eustratiadis 112) (Lauriotis & Eustratiadis 1925:12) and subjects folios to a thorough analysis in order to identify the text(s) they preserve.

The codex Athonensis, Lauras A 112 (Eustratiadis 112)

As far as it has been possible to ascertain, this codex was first described in the early 20th century by Caspar René Gregory (1909:1260). According to him, the codex dates from the 14th century. It measures 34.5 cm × 27 cm, is made of parchment and contains 300 folios. The codex is a gospel book, which at the beginning and at the end contains several folios of texts by Gregory the Theologian and John Chrysostom ('vorn und hinten Bll [Blätter] aus Greg Theol und Chrys'). Caspar R. Gregory, being interested only in the contents of the gospel book, says nothing about the number of these folios. The vague indication of the authors from whom the texts come is of no help when one considers the very extensive corpora preserved under these two patristic authors' names.

In 1925, Spyridon Lauriotis and Sophronios Eustratiadis provided a second basic description of the codex (pp. 11-12). In their brief catalogue entry, they describe this codex as made of parchment, measuring 35 cm × 25 cm, and dating from the 10th century. The manuscript's place of origin is unknown, and no hypothesis has been formulated with regard to its provenance. The codex is said to contain an Evangelion, with three and four folios added at the beginning and end, respectively. According to Lauriotis and Eustratiadis, the three folios added at the beginning contain two homilies of Gregory the Theologian, and the four folios added at the end preserve a homily on the paralytic by John Chrysostom (ἐν ἀρχῇ τρία φύλλα πρόσθετα περιέχουσι δύο λόγους Γρηγορίου τοῦ Θεολόγου· ἐν τέλει 4 ἕτερα περιέχουσι λόγον τοῦ Χρυσοστόμου εἰς τὸν παραλυτικόν; Lauriotis & Eustratiades 1925:12).

The last four folios

It should be noted at the outset that due to the extensive ongoing renovations that have been taking place for several years in the main building of the library of the Great Lavra Monastery on Mount Athos, it was not possible to make an in situ examination of the codex. Thanks to the Patriarchal Institute for Patristic Studies in Thessaloniki (Greece), however, the author of the present article was able to examine a microfilm reproduction of the manuscript's last four folios. These folios are numbered 297-300. The text is written in two columns of 35 lines. Strikingly, all four folios share a peculiarity. The right-hand side of the folios has been mutilated, and in some places even the letters in the margin of the column have been mutilated. A strip has been subsequently glued to the verso so that the size of these last four folios in the codex is identical to that of the other folios. The four glued strips also come from a parchment manuscript, having been written on both sides. Although their size is small, it is still possible to read one or more words on a line and thereby attempt to identify the text they preserve. The hand that wrote the text on the pasted strips is the same hand that wrote the last four folios preserved in the codex, but this hand is not that of the copyist who transcribed the Evangelion.

For the sake of clarity, in what follows, the number of the folio, recto or verso, and the column (a or b) are all indicated. Also, text that is illegible in the microfilm has been placed between brackets.

The first lines of column a of folio 297r read as follows: <…->θησαν· ταύτας τὰς χεῖρας θεωρήσας ὁ Πέτρος ἐβόα καὶ προσηύχετο ἐν τῇ φυλακῇ τὰ τοῦ Δαυῒδ ῥήματα λέγων· Μὴ συναπολέσῃς μετὰ ἀσεβῶν τὴν ψυχήν μου καὶ μετὰ ἀνδρῶν αἱμάτων τὴν ζωήν μου, ὧν ἐν χερσὶν αἱ ἀνομίαι· ἡ δεξιὰ αὐτῶν ἐπλήσθη δώρων. A search of the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae (TLG) database3 reveals that the above fragment is from the Homilia in mediam Pentecosten (CPG 7888; BHG 1488e) by the enigmatic priest Leontius of Constantinople (Sachot 1977:244). Reading on, we discover that the two columns of folio 297r contain, with very slight differences, the last part of Leontius' homily, namely, lines 471-504 of the critical edition published by Cornelis Datema and Pauline Allen (1987:313-337, here 335-337). Following the apparatus criticus provided by Datema and Allen, it can be seen that the fragment transmitted by the Lavra codex has variant readings in common with the large group of manuscripts which the editors refer to as ω1 (Datema & Allen 1987:308-309). A connection can also be seen with the branch α distinguished by the editors within the ω1 group of manuscripts, particularly with Vindobonensis theologicus gr. 5 (dated 948) (V)4 and Parisinus gr. 771 (14th century) (Z). In terms of content, the fragment speaks of the murder of James, the imprisonment of the apostle Peter and Herod's intention to kill Peter after the Passover, thereby providing an interpretation of Acts 12:1-4 (Allen & Datema 1991:122-135).

Examining the folios further, it becomes evident that the first lines of column a from folio 297v preserve the end of Leontius' homily Homilia in mediam Pentecosten, namely, lines 504-508 in the critical edition by Datema and Allen (1987:337). Column a of folio 297v continues with another homily, which is ascribed to John Chrysostom. The homily is entitled Ἰω<άννου> ἀρχιεπισκόπου Κωνσταντινουπόλεως τοῦ Χρ<υσοστόμου> εἰς τὸν παράλυτον ἐλέχθη τῇ Μεσοπεντηκοστῇ καὶ εἰς Μὴ κρίνετε κατ' ὄψιν. The homily is none other than the Oratio in mesopentecosten (CPG 3236), included in Migne's Patrologia Graeca among the works of Amphilochius of Iconium (ed. Migne 1862:39:119-130). The fact that it has been transmitted mainly as a sermon on Mid-Pentecost by John Chrysostom5 led Datema to place this sermon among the spuria of Amphilochius in his critical edition of that author's works (Datema 1978:245-262).6 The title of the homily does not seem to be attested by any of the manuscripts collated by Datema for his critical edition. Columns a and b of folio 297v preserve lines 5-29 of Datema's edition (1978:251-252). One can, however, observe several variant readings in common with the ω2 group of manuscripts, notably Atheniensis EBE 457 (16th century) (B). As for the content of the text, after the opening words, two sayings of Jesus from the gospel according to John (5:8 and 7:16) are very briefly quoted. Then, in an address to the listeners, the homilist indicates that the Lord spoke these words because of the healing of the paralytic (Jn 5:1-15), an account of which has just been read to the congregation, most likely at the celebration of the Eucharist. There follows an excursus on the equality of the Father and the Son and an affirmation that the Father, Son and Holy Spirit teach the same doctrine.

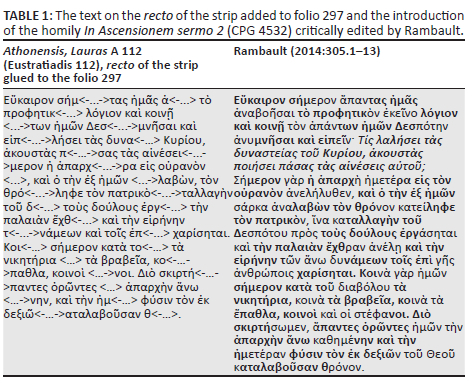

The text that can be discerned on the recto of the strip glued to the edge of folio 297 is the beginning of a homily. Although some of the letters are not legible due to the mutilation of the strip, it is possible to discern the following title: Τοῦ ἐν ἁγίοι<ς> Ἰω<άννου> τοῦ Χρ<υσοστόμου> εἰς <τὴν> ἀνάληψιν τ<οῦ Κυρίου> ἡμῶν Ἰ<ησο>ῦ Χ<ριστο>ῦ. Further on the it is possible to read: Εὔκαιρον σήμ<-…->τας ἡμᾶς ἀ<-…> τὸ προφητικ<-…> λόγιον καὶ κοινῇ <…->των ἡμῶν Δεσ<-…->μνῆσαι καὶ εἰπ<-…->λήσει τὰς δυνα<-…> Κυρίου, ἀκουστὰς π<-…->σας τὰς αἰνέσει<-…->μερον ἡ ἀπαρχ<-…->ρα εἰς οὐρανὸν <…>. Both the title and the incipit of the text allow us to identify the homily as In Ascensi onem sermo 2 (CPG 4532), which has recently been critically edited by Nathalie Rambault (2014:263-322). The text preserved on the recto of the strip is none other than this homily's introduction (see Table 1). Furthermore, it is possible to observe that the fragment shares most of its variant readings with the manuscripts Parisinus gr. 766 (mid-9th century) (P), Hierosolymitanus S. Sepulcri 6 (10th century) (Y), Vindobonensis theologicus gr. 5 (dated 948) (F), Monacensis gr. 146 (11th century) (M), Pantocra toros 26 (11th century) (K), Parisinus gr. 1175 (11th century) (J), Marcianus gr. II.46 (13th century) (G). In terms of content, the homily begins with a burst of joy in an almost hymnographic style and sums up in a few formulas the importance of Christ's Ascension in the economy of salvation. The author of the homily exclaims that the feast of the Lord's Ascension is a fitting time to praise Christ, the Lord of all, in hymns, because:

[T]oday our fellowship has been lifted up to heaven, and He who took flesh from us has sat on the Father's throne, that He might work reconciliation between the Master and his servants and destroy the old enmity and give peace to humankind.

On the verso, the following can be read: <…->α πληρῶν τοῦ κε<-…->ος λέγων πρὸς αὐτούς· <…->ας με ὑγιῆ, ἐκεῖνός <…> Ἆρον τὸν κράββα<-…> καὶ περιπάτει. The fragment is the end of the homily Oratio in mesopentecosten (CPG 3236), namely, lines 227-240 of Datema's edition (1978:261-262), in which the author of the homily treats the last part of the Johannine narrative about the healing of the paralytic at the pool of Bethesda (Jn 5:10-14), then offers a final exhortation and concludes the sermon with a doxology. Following the editor's critical apparatus, it is apparent that their text shares variant readings with the group ω2, particularly the Parisinus gr. 582 (10th century) (A) and Atheniensis EBE 457 (B), the latter being very close to the former (Datema 1978:248).

We then come to folio 298. In the first lines of column a on folio 298r, one can read: καὶ σωθῇς, ἵνα ὅταν παραγένωμαι κριτὴς ζώντων καὶ νεκρῶν, ὑποδείξω τοῖς ἐχθροῖς τὴν πληγὴν καὶ κατακρίνω τὴν θεομάχον συναγωγὴν, ἵνα ἴδωσιν Ἰουδαῖοι εἰς ὃν ἐξεκέντησαν καὶ προσκυνήσουσιν πιστεύοντες. Καὶ ἀπεκρίθη Θωμᾶς καὶ εἶπεν αὐτῷ· «Ὁ Κύριός μου καὶ ὁ Θεός μου»· πιστεύω τὴν ἀναστασίν σου, Δέσποτα, πιστεύω τῇ νίκῃ σου, βασιλεῦ. The text in the two columns of folio 298r comes from the homily In s. apostolum Thomam (CPG 5832), unanimously attributed by the manuscript tradition to John Chrysostom but restored by Leroy to Proclus of Constantinople (Leroy 1967:230). This text is paragraphs 11.40.4 to 13.47.4 of the homily (Leroy 1967:245-247). Following Leroy's apparatus criticus, it is evident that the variant readings have the most in common with the following manuscripts: Hierosolymitanus S. Sabae 1 (10th century) (S), Hierosolymitanus S. Sepulcri 6 (10th century) (T), Oxoniensis Bodl. Baroccianus 241 (14th-15th centuries) (N), Vaticanus gr. 2079 (9th-10th centuries) (X). With regard to its content, the fragment contains the last words of Jesus' invitation to Thomas to touch him and Thomas' credo. Thomas confesses his faith in Jesus' resurrection, in his victory, and he asserts that from now on he need not seek more. Thomas confesses that he now truly knows who Jesus is: 'my God and Lord', 'truly God and really man' (Barkhuizen 2001:189-190).

On the verso, folio 298 also preserves a fragment of the homily In s. apostolum Thomam in the two columns. This is paragraph 13.47.4-14.54.3 (Leroy 1967:247-249). One should note that the strip pasted on the verso of this folio covers in places the first letter or letters of the lines in column a. Again, one can find common readings with the codex Hierosolymitanus S. Sabae 1 (S), Hierosolymitanus S. Sepulcri 6 (T), and Vaticanus gr. 2079 (X). In its content, the fragment contains 'the final part of Thomas' credo' (Barkhuizen 2004:32) and the beginning of a response by Jesus that blesses those who, without seeing or touching, believe in him. They are blessed because through faith they see the Unseen One.

On account of the excessive mutilation, it is scarcely possible to read a word or a few letters on each line on the recto of the strip added to folio 298. However, it was not impossible to identify the preserved text. It too is a passage from the homily In s. apostolum Thomam, exactly paragraphs 14.54.3 to 15.58.3 of Leroy's edition (Leroy 1967:249-250). Following the variant readings given by Leroy in the apparatus criticus of his edition, it is again evident that the text transmitted by their codex shares many readings with three other 10th-century codices that transmit this homily: Hierosolymitanus S. Sabae 1 (S), Hierosolymitanus S. Sepulcri 6 (T), and Vaticanus gr. 2079 (X). In terms of content, the fragment contains the final part of Jesus' response to Thomas' credo and an exhortation by the author that his listeners approach Christ with pure hearts. This exhortation is followed by a prayer to the Lord.7 On the verso, the strip attached to folio 298 preserves a fragment from the beginning of Leontius of Constantinople's Homilia in mediam Pentecosten (CPG 7888). These are lines 4-25 of the edition published by Datema and Allen (1987:313-314), in which Leontius provides 'an exposition on the nature of the feast' (Allen & Datema 1991:118).

The two columns of folio 299r preserve another fragment of the Homilia in mediam Pentecosten (CPG 7888) by Leontius. These are lines 105-144 of the edition published by Datema and Allen (1987:318-320). In the case of this fragment too, one can observe, by following the apparatus criticus of the editors, the variant readings common to the group ω1 and in particular the branch α. The content of the fragment is 'a lively altercation between the homilist and the Jews … in the course of which reference is made to the cure of the man blind from birth' (Allen & Datema 1991:118).

The two columns on the verso of folio 299 continue the Homilia in mediam Pentecosten (CPG 7888) by Leontius. These are lines 144-180 of the edition published by Datema and Allen (1987:320-322). This passage also shares variant readings with the group ω1, and with the textus vulgatus of Migne's edition, especially branch α. A variant in common with Parisinus gr. 771 (both omit ἄσβεστον from the sentence ἔχει γὰρ λάμπουσαν, ἄσβεστον τὴν λαμπάδα τῆς πίστεως, lines 145-146, ed. Datema & Allen) may lead to placing the text in a closer relationship to this manuscript. There is another omission in Parisinus gr. 771 (it omits τά from the sentence Ἐλισσαῖος δὲ τὰ ὅμοια αὐτῷ οὐ διεπράξατο;), which is not found in the manuscript. In their content, the passages present 'a vivacious debate between the Jews and the blind man' (Allen & Datema 1991:118).

On the recto of the strip added to folio 299, it is possible to identify, albeit with some difficulty, yet another fragment of the beginning of Leontius' Homilia in mediam Pentecosten (CPG 7888). This fragment preserves lines 25-44 of the edition published by Datema and Allen (1987:314-315). Although the text is very mutilated, one can still see the connection with the ω1 manuscript group and the textus vulgatus of Migne's edition. In content, the fragment comes from the introductory part of the sermon, in which the author gives an exposition on the nature of the feast, which is the midpoint 'of the resurrection of the Master and the coming of the Holy Spirit' (Allen & Datema 1991:122). On the verso, the strip added to folio 299 also preserves a fragment of the Homilia in mediam Pentecosten (CPG 7888), lines 85-105 of the edition published by Datema and Allen (1987:317-318). As in the case of the recto of the strip, the connection with the ω1 group and the textus vulgatus of Migne's edition is visible, as shown for example in the omission of an entire sentence (line 100 of Datema & Allen's edition). In terms of content, the fragment is the very beginning of the 'altercation between the homilist and the Jews', which started with the latter's accusation that Jesus was possessed by a demon (Jn 7:20) (Allen & Datema 1991:118).

The last folio of the Lavra codex preserves on the recto, in both columns, another fragment of the homily In Ascensionem sermo 2 (CPG 4532), namely, lines 25-52 of Rambault's recent edition (pp. 307-309). A close look at Rambault's critical apparatus reveals that the manuscript has the most variant readings in common with the manuscripts Parisinus gr. 766 (P), Hierosolymitanus S. Sepulcri 6 (Y), Monacensis gr. 146 (M), Athonensis Pantokratoros 26 (K), Parisinus gr. 1175 (J), Marcianus gr. II.46 (G). But again, when a reading is attested by only one of these manuscripts, that reading is not found in the Lavra codex, which prevents us from establishing a closer relationship between it and the rest of the tradition. With regard to content, the fragment includes the homilist's emphasis on the soteriological role of Christ's Ascension, whereby people become co-heirs with the Son. It is affirmed that Christ is God and that his Incarnation is not incompatible with his presence in heaven.

The text continues in the two columns on the verso of folio 300, which contain lines 52-79 of Rambault's recent edition (pp. 309-313). Following Rambault's critical apparatus, it is again possible to see that the text in the Lavra codex has the most readings in common with the group of manuscripts formed by P, Y, M, K, J, G, especially Y and P. But when a particular reading is attested only by Y or P, that reading is not found in the Lavra codex. In terms of content, the fragment develops the idea that Christ assumed a human body out of his love for humankind in order to reconcile them to the Father and that the Holy Spirit was sent as a guarantee of reconciliation.

On the recto of the strip added to folio 300, a fragment of the Oratio in mesopentecosten (CPG 3236) can be identified, namely lines 43-59 (Datema 1978:253). As the text is very mutilated, it was only possible to observe, with regard to common variant readings with other manuscripts that transmit this homily, that there is a common reading with Vaticanus gr. 1587, (dated 1389) (R), Hierosolymitanus S. Sepulcri 6 (H), Parisinus gr. 582 (A) and Atheniensis EBE 457 (B).8 With respect to its content, this fragment preserves the first part of an elaborate speech by Jesus to the Jews, starting from the text of John 7:23-24, in which he asks them to tell him why they accuse him of breaking the Sabbath by healing the paralysed man, since they are circumcising on the Sabbath precisely in order not to break the law of Moses. The fragment on the recto of the strip attached to folio 300 continues on the verso and preserves lines 60-75 of Datema's edition (1978:254). As for its possible relation to a group of manuscripts, in the very mutilated text, a common reading with Athonensis Pantokratoros 3 (13th century) (Q), Vaticanus gr. 1587 (R) and the ω2 manuscript group can be discerned (Datema 1978:254.70). With regard to content, the fragment contains the second part of Jesus' speech to the Jews.

Concluding remarks

The first observation to be made after examining the last four folios of the codex Athonensis, Lauras A 112 is that the description given by Lauriotis and Eustratiadis is inaccurate. These folios do not preserve a homily on the healing of the paralytic by John Chrysostom, but they rather contain several fragments of homilies on Thomas, Mid-Pentecost and the Ascension. More precisely, the homilies in question are In s. apostolum Thomam (CPG 5832), Homilia in mediam Pentecosten (CPG 7888), Oratio in mesopentecosten (CPG 3236) and In Ascensionem sermo 2 (CPG 4532). Although preserved only in fragments in the last four folios of the Lavra codex, for two (In s. apostolum Thomam and Oratio in mesopentecosten) of the four homilies the title is preserved. Both are attributed to John Chrysostom. Modern scholars, however, no longer share the copyist's belief in the Chrysostomic authorship of these two texts. The homily In s. apostolum Thomam was restored by Leroy to Proclus of Constantinople, and it is listed in the Clavis Patrum Graecorum among the writings of Proclus of Constantinople, while the Oratio in mesopentecosten, according to Martin Kaiser's thorough analysis of the text as it has come down to us, cannot be wholly by Amphilochius of Iconium, although some parts may come from him (Kaiser 2016:137).9 If one wonders what led the cataloguers to state that the folios preserve a homily on the healing of the paralytic by John Chrysostom, it is quite possibly due to the title of the homily beginning on f. 297v (Ἰω<άννου> ἀρχιεπισκόπου Κωνσταντινουπόλεως τοῦ Χρ<υσοστόμου> εἰς τὸν παράλυτον ἐλέχθη τῇ Μεσοπεντηκοστῇ καὶ εἰς Μὴκρίνετεκατ' ὄψιν).

To summarise, the last four folios of the Lavra codex contain the following:

-

Folio 297r: Leontius of Constantinople, Homilia in mediam Pentecosten (CPG 7888), Datema and Allen (1987:335-337), lin. 471-504.

-

Folio 297v: Leontius of Constantinople, Homilia in mediam Pentecosten (CPG 7888), Datema and Allen (1987:337), lin. 504 usque ad finem, lin. 508; Pseudo-Amphilochius of Iconium, Oratio in mesopentecosten (CPG 3236), Datema (1978:251-252), titulus et inc. usque ad lin. 29.

-

Recto of the strip added to folio 297: Pseudo-Chrysostom, In Ascensionem sermo 2 (CPG 4532), Rambault (2014:305), titulus et inc. usque ad lin. 13.

-

Verso of the strip added to folio 297: Pseudo-Amphilochius of Iconium, Oratio in mesopentecosten (CPG 3236), Datema (1987:261-262), lin. 227 usque ad finem, lin. 240.

-

Folio 298r: Proclus of Constantinople, In s. apostolum Thomam (CPG 5832; BHGa 1839), Leroy (1967:245-247), lin. 11.40.4 usque ad 13.47.4.

-

Folio 298v: Proclus of Constantinople, In s. apostolum Thomam (CPG 5832; BHGa 1839), Leroy (1967:247-249), lin. 13.47.4 usque ad 14.54.3.

-

Recto of the strip added to folio 298: Proclus of Constantinople, In s. apostolum Thomam (CPG 5832; BHGa 1839), Leroy (1967:249-250), lin. 14.54.3 usque ad 15.58.3.

-

Verso of the strip added to folio 298: Leontius of Constantinople, Homilia in mediam Pentecosten (CPG 7888), Datema and Allen (1987:313), lin. 4-25.

-

Folio 299r: Leontius of Constantinople, Homilia in mediam Pentecosten (CPG 7888), Datema and Allen (1987:318-320), lin. 105-144.

-

Folio 299v: Leontius of Constantinople, Homilia in mediam Pentecosten (CPG 7888), Datema and Allen (1987:320-322), lin. 144-180.

-

Recto of the strip added to folio 299: Leontius of Constantinople, Homilia in mediam Pentecosten (CPG 7888), Datema and Allen (1987:314-315), lin. 25-44.

-

Verso of the strip added to folio 299: Leontius of Constantinople, Homilia in mediam Pentecosten (CPG 7888), Datema and Allen (1987:317-318), lin. 85-105.

-

Folio 300r: Pseudo-Chrysostom, In Ascensionem sermo 2 (CPG 4532), Rambault (2014:307-309), lin. 25-52.

-

Folio 300v: Pseudo-Chrysostom, In Ascensionem sermo 2 (CPG 4532), Rambault (2014:309-313), lin. 52-79.

-

Recto of the strip added to folio 300: Pseudo-Amphilochius of Iconium, Oratio in mesopentecosten (CPG 3236), Datema (1987:253), lin. 43-59.

-

Verso of the strip added to folio 300: Pseudo-Amphilochius of Iconium, Oratio in mesopentecosten (CPG 3236), Datema (1987:254), lin. 60-75.

From the above, it is evident that the actual numbering of the folios is subsequent to the binding of the codex. We would be right to wonder what might be the reason for placing these folios at the end of the Evangelion in a chaotic order, one that in no way points to the intention of appending a text to the end of the gospel book. A reasonable hypothesis is that the four folios at the end of the codex, like the three folios at the beginning of the codex (numbered as folios 1-3), were used as a covering for the Evangelion. The first two folios show the same features as folios 297-300. As their original size was smaller than that of the Evangelion's folios, a strip of the same manuscript was added to them so that their size was the same as that of the Evangelion's folios. Folio 1r-v preserves a fragment of the homily In s. apostolum Thomam (CPG 5832) and folio 2r-v a fragment of Leontius of Constantinople's Homilia in mediam Pentecosten (CPG 7888). Folio 3r-v differs in size and in the number of lines per column from the first two folios, but it is the same size as folios 4-296. It contains the beginning of Gregory the Theologian's homily In Pentecosten (Oratio 41) (CPG 3010.41; ed. Migne 1862:36:428.52-429.21).

May the act of those who bound the codex, a very practical act in itself, in order to protect the Evangelion, also have a deeper meaning? Are the bookbinders suggesting that the writings of the church fathers ensure that the word of the gospel is preserved unaltered or that the correct understanding of the word of the gospel requires the words of the fathers?

Finally, a few remarks are in order regarding the possible origin of the last folios of the Lavra codex. Throughout the examination of the folios, the author of this article has carefully followed the variant readings that the fragments share with other manuscripts preserving these homilies, in an attempt to identify a possible ancestor of the manuscript from which the folios originate. It can be seen that only one preserves all five homilies. This is Hierosolymitanus S. Sepulcri 6 (10th century).10 Not all the homilies, however, share readings with this manuscript. In the case of homily CPG 7888, the text preserved in the Lavra codex seems to be far removed from that transmitted by the Jerusalem codex, and the same seems to be true of homily CPG 3236. Therefore, the last four folios of the codex Lauras A 112 cannot be a copy of the Jerusalem manuscript but rather are only related to it.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the Patriarchal Institute for Patristic Studies in Thessaloniki (Greece), in particular Anna G. Lyssikatou, who provided him with a microfilmed reproduction of the first and last folios of the codex Athonensis, Lauras A 112.

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

Author's contributions

R.G. is the sole author of this article.

Ethical considerations

This article followed all ethical standards for research without direct contact with human or animal subjects.

Funding information

The project was financed by Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu and the Hasso Plattner Foundation research grants (ref. no. LBUS-IRG-2020-06).

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the author.

References

Allen, P. & Datema, C. (transl.), 1991, Leontius presbyter of Constantinople: Fourteen homilies, Byzantina Australiensia 9, Australian Association for Byzantine Studies, Sydney. [ Links ]

Aubineau, M., 1968, Codices Chrysostomici Graeci. I: Codices Britanniae et Hiberniae, Éditions du Centre national de la recherche scientifique, Paris. [ Links ]

Barkhuizen, J.H. (transl.), 2001, Proclus, bishop of Constantinople: Homilies on the life of Christ, Early Christian Studies 1, Australian Catholic University, Brisbane. [ Links ]

Barkhuizen, J.H., 2004, 'Thomas - Portrait of an apostle: Proclus Constantinopolitanus and Romanus Melodus', Acta Patristica et Byzantina 15(1), 22-37. https://doi.org/10.1080/10226486.2004.11745733 [ Links ]

Bonnet, M. & Voicu, S.J., 2012, Amphiloque d'Iconium: Homélies, Sources Chrétiennes 552-553, Cerf, Paris. [ Links ]

Datema, C., 1978, Amphilochii Iconiensis Opera, Corpus Christianorum Series Graeca 3, Brepols/Leuven University Press, Turnhout. [ Links ]

Datema, C. & Allen, P., 1987, Leontii Presbyteri Constantinopolitani Homiliae, Corpus Christianorum Series Graeca 17, Brepols, Turnhout. [ Links ]

Ehrhard, A., 1937, Überlieferung und Bestand der hagiographischen und homiletischen Literatur der griechischen Kirche von den Anfängen bis zum Ende des 16. Jahrhunderts, Band I, Texte und Untersuchungen zur Geschichte der altchristlichen Literatur 50, J.C. Hinrichs Verlag, Leipzig. [ Links ]

Geerard, M., 1974, Clavis Patrum Graecorum II: ab Athanasio ad Chrysostomum, Brepols, Turnhout. [ Links ]

Gregory, C.R., 1909, Textkritik des Neuen Testamentes, vol. 3, J. C. Hinrichs'sche Buchhandlung, Leipzig. [ Links ]

Kaiser, M., 2016, 'Die (pseudo-amphilochianische) Mesopentekoste-Predigt CPG 3236', in R.W. Bishop, J. Leemans & H. Tamas (eds.), Preaching after easter: Mid-Pentecost, ascension, and Pentecost in late antiquity, Supplements to Vigiliae Christianae 136, pp. 120-137, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Lauriotis, S. & Eustratiadis, S., 1925, ΚατάλογοςτῶνκωδίκωντῆςΜεγίστηςΛαύρας (τῆςἐνἉγίῳὌρει). Ἐπλουτίσθηκαὶδιὰτῶνἐντέλειδύοπαραρτημάτωνκαὶτῶνἀναγκαιούντωνεὑρετηρίωνπινάκων. Catalogue of the Greek manuscripts in the library of the Laura on Mount Athos, with notices from other libraries, Harvard Theological Studies 12, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. [ Links ]

Leroy, F.J., 1967, L'homilétique de Proclus de Constantinople: Tradition manuscrite, inédits, études connexes, Studi e testi, 247, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Città del Vaticano. [ Links ]

Migne, J.-P. (ed.), 1862, Patrologiae cursus completus: Series graeca, 162 vols., Migne, Paris. [ Links ]

Papadopoulos-Kerameus, A., 1891, ἹεροσολυμιτικὴΒιβλιοθήκηἤτοικατάλογοςτῶνἐνταῖςβιβλιοθήκαιςτοῦ…ὀρθοδόξουπατριαρχικοῦθρόνουτῶνἹεροσολύμων…ἀποκειμένωνἑλληνικῶνκωδίκων, vol. 1, Kirspaoum, Petropoli [Sankt-Peterburg]. [ Links ]

Rambault, N., 2014, 'In Ascensionem sermon 2 (CPG 4532): une recopilation realisée entre la fin du VIe et le VIIe siècle: Édition critique, traduction et étude', Sacris Erudiri 53, 263-322. https://doi.org/10.1484/J.SE.5.103646 [ Links ]

Sachot, M., 1977, 'Les homélies de Léonce, prêtre de Constantinople', Recherches de Sciences Religieuses 51(2-3), 234-245. https://doi.org/10.3406/rscir.1977.2793 [ Links ]

Θεῖον Προσευχητάριον, 1993, ἐκδίδεταιἀναλώμασικαίἐπιμελείᾳὑπότοῦἘπισκόπουΟἰνόηςΜατθαίουΛαγγῆ, 11η [ Links ] ἔκδοσις, Ἐκδόσεις Μεγάλου Συναξαριστῆ, Ἀθῆναι.

Thesaurus Linguae Graecae (TLG), n.d., A digital library of Greek literature, A Special Research Program at the University of California, Irvine, viewed 04 June 2022, from http://stephanus.tlg.uci.edu/index.php. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Radu Gârbacea

radu_garbacea@yahoo.com

Received: 27 June 2022

Accepted: 09 Aug. 2022

Published: 15 Dec. 2022

Project Leader: J. Pillay

Project Number: 04653484

Description: The author is participating as the research associate of Dean Prof. Dr Jerry Pillay, Faculty of Theology and Religion, University of Pretoria.

Note: Special Collection: Orthodox Theology in Dialogue with other Theologies and with Society, sub-edited by Daniel Buda (Lucian Blaga University, Romania) and Jerry Pillay (University of Pretoria).

1 . The author is preparing an edition of the two homilies with Guillaume Bady, to whom he is very grateful for all his support. For the homily In paralyticum (CPG 4978), only one manuscript witness is known, codex Parisinus graecus 1173A, saec. XII-XIII, ff. 209r-210r, housed in the Bibliothèque Nationale of France in Paris (Geerard 1974:636). A copy of the manuscript is accessible online at https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10721781z/f218.item.zoom, last accessed 04 April 2022. The homily In paralyticum (CPG 5055) is preserved, according to the Pinakes database, in seven codices (https://pinakes.irht.cnrs.fr/notices/oeuvre/8308/, last accessed 04 April 2022). In the alphabetical index of Chrysostom's writings at the end of volume 64 of the Patrologiae Graecae, the homily CPG 5055 is entitled In Mesopentecosten (Migne 1862:64:1417-1418). In the first volume of the Codices Chrysostomici Graeci edited by Michel Aubineau, the homily has the title In paralyticum (Aubineau 1968:194-195). The editor of the second volume of the Clavis Patrum Graecorum has chosen the title In paralyticum for the homily inventoried under the reference number 5055 (Geerard 1974:647). The title In paralyticum does not seem to be supported by the manuscript evidence. For example, the codex Oxoniensis Bodl. Baroccianus 174, saec. X, ff. 41r-43r, preserves the text with the title: Τοῦ αὐτοῦ εἰς τὴν αὐτὴν ἑορτὴν· λόγος γ΄; the codex Marcianus graecus II.46 (coll. 1014), saec. XIII, ff. 234v-236v: Τοῦ ἐν ἁγίοις πατρὸς ἡμῶν Ἰωάννου τοῦ Χρυσοστόμου, λόγος εἰς τὴν μεσοπεντηκοστήν; the codex Oxoniensis Bodl. Baroccianus 212, saec. XVI, ff. 290v-291v: Τοῦ αὐτοῦ εἰς τὴν μεσοπεντηκοστήν.

2 . https://pinakes.irht.cnrs.fr/notices/oeuvre/12926/, last accessed 04 April 2022.

3 . http://stephanus.tlg.uci.edu/index.php, last accessed 04 June 2022.

4 . The letter V is the siglum used by the editors for Vindobonensis theologicus gr. 5. After indicating the name of each manuscript, the author notes the siglum assigned to it by the editors of the text in question.

5 . In only one of 14 manuscripts collated by Datema is the sermon attributed to Amphilochius, and even there the attribution was deleted by a later hand. The manuscript in which the name Amphilochius is found is the codex Mosquensis graecus 217 (234). In this manuscript, the sermon's initial words - present in all the other witnesses - are lacking (Kaiser 2016:123).

6 . For a useful overview of the issues of authorship and the structure of the text, see Kaiser 2016. The sermon is not included in the new edition of the works of Amphilochius by Michel Bonnet and Sever J. Voicu (Bonnet & Voicu 2012).

7 . To the author's knowledge, no one has noticed before that this prayer is one of the 12 preparatory prayers for Holy Communion in the Byzantine tradition. The prayer preserved in the sermon is the fourth of these prayers and is traditionally attributed to St John Chrysostom (Θεῖον Προσευχητάριον 1993:203-204).

8 . In these manuscripts, it reads ἐπὶ τριάκοντα καὶ ὀκτὼ ἔτη instead of ἐπὶ τριακονταοκτὼ ἔτη, which is adopted by the editor of the critical edition.

9 . Regarding the authorship of the text, it should also be noted from Kaiser's analysis that the exegetical parts of the sermon are close to the style of Leontius of Constantinople and that the content of the Trinitarian section would not be out of character in late 4th-century Cappadocia (Kaiser 2016:137).

10 . In its present form, the codex is by no means a unified collection written by several hands, as presented by Athanasios Papadopoulos-Kerameus (1891:19-30) but rather a manuscript which originally had 12 texts, to which many other texts were added later (Ehrhard 1937:174-175).