Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

HTS Theological Studies

On-line version ISSN 2072-8050

Print version ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.78 n.1 Pretoria 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v78i1.7930

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Reappraising the Nsukka Ọmabe festival through the lens of ethno-aesthetics, therapy and healing

Martins N. Okoro

Department of Fine and Applied Arts, Faculty of Arts, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Enugu, Nigeria

ABSTRACT

In Igbo traditional religion (ITR), there are different means through which therapy and healing are achieved. One such means is through the Nsukka-Igbo Ọmabe masquerade festival rituals and performance theatre. To seek out this aspect of the cultural festival that has been under-researched, this study delves into detailed discussions of the pre-arrival, arrival, events in between, departure and postdeparture of the Ọmabe masquerade festival. Relying on a qualitative method, the study analytically and descriptively discusses the data gathered through participatory observations and interview sessions with some of the devotees possessing sufficient knowledge of the masquerade tradition and festival. Photographs have been included to flesh out the narratives, as well as enrich and enhance the readers' engagement with the article. Also, relevant materials from extant literature are quoted and cited. The study examined the rituals, music, performances and other interesting key components of the festival and found that the traditional practice through masquerade festivals such as the Ọmabe is therapeutic, leading to emotional activation and healing. Undoubtedly, this has been sustaining its re-enactments in the face of neoreligious intolerance, urbanisation, modernity and globalisation that have been adversely affecting cultural practices.

CONTRIBUTION: The article critically engages with the reappraisal of the Ọmabe cultural heritage festival among the Nsukka-Igbo people, providing thought-provoking, impactful research as well as insightful reading towards achieving an understanding of its rituals, materiality and performance theatre and their accompanying therapy and healing benefits. Bearing in mind that HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies focuses on religious issues and that the 'masking festival' is a part of Indigenous religious practice, the author considers this article to be suitable for its objectives.

Keywords: Ọmabe; masquerade; festival; ethno-aesthetics; therapy; healing; Nsukka-Igbo.

Introduction

A thorough grasp of the worldview of any given group of people is a fundamental prerequisite for the understanding of the rest of the interconnected belief, ideas, values and practices of the group (Kalu 2022). Towards understanding the worldview of the Nsukka-Igbo people, particularly in the aspect of the Ọmabe masquerade, several studies (Aniakor 1976, 1988; Asogwa & Duniya 2017; Asogwa & Odoh 2022; Nwoko 1989; Ugwu 2011) have been carried out. Unfortunately, none of these studies touches on this traditional festival and its implications on therapy and healing and general well-being, given that a subject such as traditional festival and its implication on therapy, healing and general well-being ought to stimulate the intellect in search of new conceptual directions. These, therefore, have stimulated as well as spurred the researcher to undertake this aspect of Igbo traditional religion (ITR), whose aesthetics, therapeutic and healing potentials are of enormous benefit to the devotee of the Ọmabe in Nsukka-Igbo.

Ngele et al. (2017) have observed that 'for the Igbo, the sum total of their views about the world and life generally is very much shaped by their religion'. This is in line with the postulation of Agbo, Opata and Okwueze (2022) that in many African societies, the worldview of Nsukka people is anchored in religion. In other words, every human experience within a group is interpreted through religion. Without disputing it, Nsukka (Igbo) people are predominantly Christians. However, there are remnants of the 'dying' African traditional religion (ATR) in the area. Among the remnants of ATR is the Nsukka Ọmabe masquerade festival that is usually celebrated triennially in a particular season set aside for it, depending on when the crescent moon is sighted. Even though the Ọmabe is an exclusively male prerogative, in very rare cases, a woman who has reached menopause and has taken the Ọyịmaa title and, as it were, has become a 'man'1 is allowed full participation in the festival and can also acquire and own costumes for the masquerade, which is enacted by some young men. A good example is Celestina Ezema, an Ọyịmaa whom young men, namely Manevmaa and Chidebere, volunteered to enact her Echaricha masquerades. In so doing, the saying that Onyenye mụrụ maa, me ọmag maa [even though women begot masquerades, they do not know it] no longer refers to her. Rather, she is referred to as Nemaa, or mother of masquerade, one who has acquired the power of divination and healing of the sick through the Ọmabe spirit.

There are different peculiar types of Ọmabe masquerades in Nsukka, namely Ishimaa [the heads of masquerades], Ediogbene, Echaricha and Oriọkpa. While some are aggressive and entertaining, some are ritualistic and wield charms to ward off danger as well as cast out spells. For example, Ediogbene and Oriọkpa are aggressive, Echaricha entertains and others, collectively referred to as the Ishimaa, fall into the ritualistic category that could curse or bless as well as exorcise. These Ọmabe masquerades are identified based on their structural features, recognisable through costumes, head structures and performances.

The Ọmabe festival is carried out with elaborate and frivolous feasting during stages such as the pre-arrival, arrival, events in between, departure and postdeparture. This study examined these stages, relying on qualitative methods. It analytically and descriptively discussed the data gathered through participatory observations and interview sessions with some of the adherents and devotees of ITR who are knowledgeable enough in the masking tradition and festival. It also relied on extant literature and included photographs so as to flesh out the narratives. It is within the realm of ethno-aesthetics, therapy and healing that the Ọmabe festival among the Nsukka-Igbo, Nigeria, is adequately studied. The study found that the Ọmabe traditional festival rituals, materiality and performance theatre as an aspect of ITR hankers on the general well-being of the followers. This may be one of the contributing factors to the growing interest in cultural practices among the growing adult population of Nsukka (Uwagbute 2021), despite the fact that 'the colonial and other contacts have laced the autochthonous culture with extraneous value', according to Ikwuemesi and Onwuegbuna (2017), and despite the fact that of the various acculturative forces that have strongly influenced Igbo people, Christian evangelism and Pentecostalism have dealt the most severe blows to Igbo cultural institutions (Gore 2008). This article, it is hoped, will stimulate new research directions towards reappraising the theme of Ọmabe masquerade.

Pre-arrival festival of the Ọmabe masquerade

The Ọmabe masquerade is believed to be a pageant from the other world that arrives for a brief sojourn in Nsukka for aesthetic entertainment and with therapeutic purposes, among others. Before its arrival, it is incumbent on the guardian known as Egbe-ochal to announce in an esoteric language, understood only by the initiated, a request for kegs (Obele ngala) of palm wine, goat meat (Ọgbụrụgbụ) and delicacies wrapped in banana leaves (ọkpa) in the next native week (native week refers to the four market days in Igbo land: Eke, Orie, Afọr and Nkwọ). The announcement, called Ọmabe ina nri, or demanding of food, is carried out in the night because Egbe-ochal must not be observed by women. On that day, at midnight, palm wine, food and meat are offered to the Ọmabe spirit. The banana leaves with which the ọkpa pudding was wrapped litter the village square, signifying Ọmabe's acceptance of the ritual. A remarkable thing that happens in the morning is that these banana leaves are picked up and cooked and the liquid substance is sieved and imbibed as a drink by the devotees as both anti-poison and antidote. The author's informant, Ezugwu,2 without equivocation, testified that it was efficacious, given the fact that he was once poisoned and when he took the remedy, it counteracted the effect of the poison. In the same vein, one interviewee, Nwadaka,3 also recalled that he had chicken pox when he was a teenager and when he drank a small amount of the water substance, it cleared completely. It is needless to say that these claims have no medical proof. It borders on a belief system, attesting to the fact of the Igbo saying that nkụ dị na mba n' eyere mba nri (the loose translation is 'the firewood fetched in a town gets their food done'), alluding to the fact that indigenous knowledge brings succour to a people.

In the harmattan season, between January and February, on different days it is incumbent on villages to carry out mgbashuete maa - a ritual of arriving with music. One of the reasons it is carried out is to bring succour to the depressed and thereby help them to avoid committing suicide. In performing this ritual, the initiated go to secluded bushes to perform this ritual in the night. Upon arrival at the place, a fire of some gathered herbs and roots is kindled. The initiated and devotees form a circle around the burning fire and warm themselves for the task ahead. The fire also illuminates the place. A ritual is performed with kola-nut, roasted yam, palm oil, a rooster and palm wine. The radicle of the kola-nut, the blood of a slaughtered rooster and a cup of palm wine are dropped, spilled and poured on the musical instruments in order to make the instruments produce good musical sound. Palm oil is used to prepare a dish of roasted yams. Following this is the playing of a stanza called ayogdi. After this, a procession starts with an accompanying shout of, 'Inyόnyόnyό u! Inyόnyόnyόnyόόό uu! Inyόόό u! Inyόόό uu!' This is a coded nonlexical term with meaning only understood by the initiated. In this procession, they go to the village squares, one after another, where devotees and the depressed dance to the sonorous music. It is a belief in Nsukka that Ọmabe music has the capacity to relieve depression and rekindle hope, thereby averting suicide. The author's informant, Ozioko,4 narrated how he faced depression which nearly pushed him into committing suicide. However, when he participated in the Ọmabe activities, especially playing Ọmabe music in the Ọmabe house, he got over it. This goes a long way in reaffirming the contestation by Aniakor (2012:80) that 'indigenous African music is a medium through which it is possible to distill the subtlest emotions at a level of apparent elusiveness'.

The nocturnal forerunner to Ọmabe, called Onyekrinye, starts moving in the night and carrying out surprises and puzzles, tying a rope from one distant tree to another and mounting some heavy objects in the middle of various roads. Also, it goes about shouting the evil committed by some unscrupulous individuals for the hearing of the community. It castigates, reveals cases of immorality and deviant behaviours and exposes criminals in society. Aniakor (2002:318) writes that 'the nocturnal mask, Onyekrinye, satirizes deviant social behaviours through its songs'. In his own view, Amankulo (2002:402) states that 'Onyekulunye characters are there to say those things which the people are unwilling to say or hear about themselves'. Ugwu (2013) posits that:

[T]he weird voice of the nocturnal agent and the fearful sound that accompanies it lend to the darkness of the night a sure feeling of spirit presence. It parades the close peripheries of people's homes, singing lampoons; calling derogatory names and exposing the deeds of criminals within the community, inviting them to repent before nemesis overtakes them from the ancestral realm. (p. 20)

It is a common saying that the fear of Onyekrinye inspires bad elements in Nsukka to turn over new leaves and become useful to society, hence the proud ascription: Emedome shi ne banyị [well-behaved persons are from our place].

Onyekrinye departs on the Eke maa day with a song:

Onyekrinye tiche'rh nkph echịcha, menya eridge, Onyekrinye alagde neh Onyekrinye alagde!

[Onyekrinye that was shouting about echịcha (a local delicacy cooked with pieces of dried cocoyam and pigeon pea or Cajanus cajan) and did not eat it, Onyekrinye is departing, Onyekrinye is departing!]

Of note is that the water used in rinsing the cocoyam before cooking is mixed together with ash and then poured across every family compound façade, so as to ward off and avert sicknesses and misfortunes during the departure. Onyekrinye's departure paves the way for the arrival of the Ọmabe masquerades on the following Orie market day. While Onyekrinye is referred to as a mask, because its operation is nocturnal, Cole and Aniakor (1984:219) argue that 'a night mask is not a mask at all but voices costumed by darkness'.

As tradition demands, devotees slaughter goats with which they entertain their guests, who come from far and near on the eke maa day to partake in the viewing of the Ọmabe masquerades the next day. On eke maa day, everyone is agog. Dane gunshots are intermittently fired into the air by devotees, amid heavy merriment and grioting - the imaginative manipulation of words, anecdotes, folklore and proverbs aimed at tracing the family histories and exploits of the devotees, as well as pronouncing and declaring sound health to them by saying: titir bụchu onyishi [sound health is more than old age]. This energises and strengthens them.

Arrival of the Ọmabe masquerades

The chief priest of the Ngwu shrine places a tuber of yam on the ground, climbs on top of a big stone and waits patiently for the masquerades, collectively known as the Maa ụtụtụ [morning masquerade]. The chief priest holds a rooster and a kola-nut, with which he makes supplications. He then pours a potent liquid substance called abogzji across the road to Ọnụnzute (a welcome point) for peace, calmness and tranquillity. This is because Ọmabe is said to carry fire which, if allowed crossing, would afflict the entire community. Chiming the iron rattles called Ikpekere, the Ishimaa masquerade called Ugwu Oyina Nwete leads the other masquerades to the Ọnụnzute and meets the chief priest of the Ngwu shrine, who comes down from the stone and hands the tuber of yam to the masquerade. Masquerades are welcomed, and pleas are made to them for good tidings and sound health, saying: 'Ọmabe masquerades, as you have come to stay with us, bless us and let us not suffer from any headaches, stomachaches or any other ailments caused by human beings or spirits'.

In the evening of the same day, devotees gather in groups, wearing different attires. In order to arouse and provoke laughter and make spectators forget their sorrows, a young man cross-dresses, appears in his mothers' dresses and mimics feminine gestures, cat-walks and beats a gong (Figure 1). Also, the village group charged with the responsibility of singing and chanting different songs boasts that their own masquerades will outperform other masquerades of the rival villages. It attests to the fact that 'masking in this sense, is one of an artistic compositions and rivalry between Igbo villages and towns in context of mask theater/spectacle (ihe nkiri)' (Aniakor 2005:15).

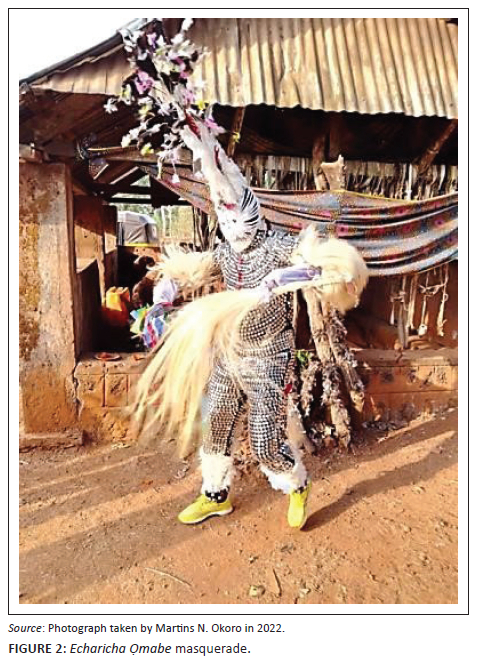

Getting to the groove called Ugwu5 Ọmabe, each village group occupies their own assigned spaces where they prepare for the materialisation of their masquerades. Of note is that at a certain stage towards the preparation, the interests of everybody shift to the Echaricha Ọmabe masquerade (Figure 2), considered to be the major performer in the event through the display of agility and flirting movements. There is no better expression to describe Echaricha than that given by Nwoko (1989), who states that it is 'the principal Ọmabe masquerade that expresses the concept of mystifying beauty, divine radiance, ideal probity and immense wealth'.

When the Echaricha masquerade is ready, the lead singer sings praise songs, followed by choruses from other singers. These praise songs are chosen for their lyrics and relevance to the performance theatre and are also illustrative of the therapeutic effect of the masquerades. With these songs, the masquerade is accompanied to various villages, the main theatres of the events, where it performed to the delight of a large audience.

Drewal (1974) writes of a popular Yoruba saying, oju to ba ri Gelede ti de opin iran [the eyes that have seen Gelede have seen the ultimate spectacle!]. Gelede is a Yoruba masquerade whose 'affective power and impact comes from its multi-media format in which the arts of song, dance, costume and music combine to create moving artistic experiences'. As a 'pageant' from the otherworld, Echaricha Ọmabe, like Gelede, is an 'ultimate spectacle' whose tightly fitted costume allows it to walk in calculative steps, at times quickly and swiftly like a duck. This explains why it is referred to as the swift entity that beat the duck in the waters during a competition. During this movement, it stretches the left hand frontward, chest out, before moving from one side to the other repeatedly with gait as it enters into the otobo [the village square], where a crowd is gathered. Its display includes turning from left to right as it vaults and lands firmly on the ground. This elicits resounding shouts of iyaaa! from the audience, a sign of confirmation that the performance is good. Loud applause from the audience serves as validation of the good performance and is also the criterion and yardstick with which to measure and rank the performance of each Echaricha Ọmabe and come to an aesthetic consensual evaluation. It is the strict adherence to these criteria that determines if an Echaricha Ọmabe has performed well or not. The decision to determine a particular Echaricha that outperforms the others would be taken unanimously by the council of title holders, arising from the level of ovation during the performance. This would be followed by the awarding the Echaricha player with a cow for an excellent performance.

The costumes of the Echaricha Ọmabe are produced by traditional artists 'equipped with the inspiration and knowledge of a variety of traditional legends, folklore and mythologies' (Fosu 1986:iv) by the elders and bought by an individual who has health issues and may have been instructed by a diviner to do so, in order for the Ọmabe spirit to heal him. Before then, such individuals would have tied some red and blue strands of cloth called ugere ekwa on an Iroko (Milicia excelsa) or Ọgbụ (Moraceae) tree serving as the Ọnụ enyanwụ [mouth of the sun] and made a promise that he would cover Ọmabe, as it were, with costumes. During an interview session, for example, Okoro6 mentioned that he had once been poisoned and was afraid that he would lose his life, but when he tied the red and blue strands of cloth and made a promise to Ọmabe and subsequently bought the costume as was instructed by a diviner, he was healed. This made him boast to the audience on the outing day of the Ọmabe masquerades, saying, 'Behold the leopard I turned into. If I go to buy costumes, I do not buy second-hand ones because of bugs, lest they bite my brother to death'. The import of this statement lies in it being a local apothegm used in keeping alive the masking tradition.

As mentioned earlier, the major function of Echaricha is to entertain the audience. What distinguishes Echaricha from other masquerades is its expensive costume made of shimmering buttons; hence, it is referred to as the enyi vuerk'h [elephant that carries wealth]. Here, an elephant is a metaphor for wealth acquisition. The features of Echaricha Ọmabe are four long white sticks decorated with many white and black feathers as the headgear; a woven face with two tiny holes that serve as the eyes; hundreds of small, round, shimmering, metallic buttons skilfully fastened on black fabric, sewn to be tightly fitted for elegant performance; and animal skin covered with some white feathers and tied between the knees and ankles of both legs. The shoulders and elbows are covered with nza ebule. The elbows and wrists are covered with white stockings. It holds a long knife and its head is tied with different free-flowing stripes of fabrics with different colours. A long padded animal skin is attached to its buttocks as the tail. On its feet is a pair of white canvas shoes. Undoubtedly, these features make it dazzling in appearance and performance.

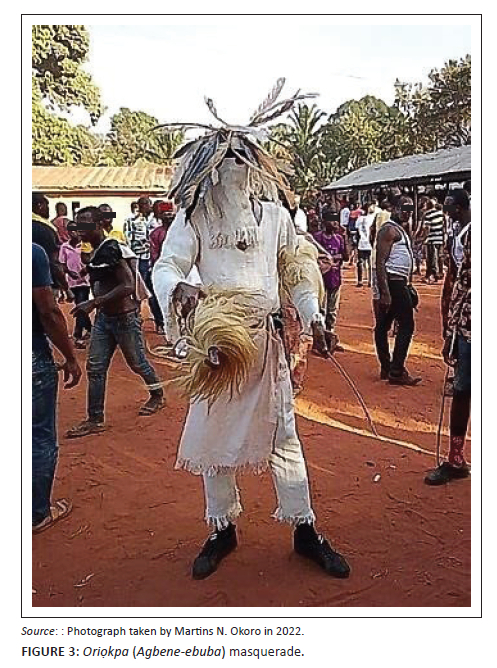

The Oriọkpa masquerade's main costumes are ekpọtọ, a locally woven fabric and feathers. There are types of Oriọkpa called Ihuojii and Agbenebụba that are identified based on their black appliqué faces and feathers on their heads; hence, they are referred to as the Ọmabe igwe ebụba, meaning 'the masquerade of many feathers' (Figure 3). The Oriọkpa ties a piece of cloth around the waist and on the elbow (nza eble). The Oriokpa also holds nza and sticks, which it uses to beat people mercilessly.

There is another type of Oriọkpa called Ugwu Udele Asogwa (Figure 4) that combines ekpọtọ with China white as its costumes. Around its head is tied a long strand of blue cloth called ugere-ekwa. It holds long and short sticks in the left and right hands, respectively. Between the shoulder and elbow are tied nza eble, which (Opata & Apeh 2018):

[I]s derived from the very long hair which comes from the neck region of the local dwarf ram (ebule). It is obtained by skinning a slaughtered ram only at the neck region in order to get the hair attached to the skin for body adornment. (p. 119)

Underneath the waist are stuffed cloths or plant fibres that make it protrude outwards. It wears a pair of canvas shoes on the feet. It moves slowly while exchanging pleasantries with the audience. It does not flog people but is known for entertaining people through humour.

Somehow, the action of the Nsukka Oriọkpa masquerade approximates that of the Efik Okpo masquerade that delights in pursuing adolescent women. This is because while the Ọriọkpa's intention is to beat girls for the simple reason that they gossip a lot, and hence it refers to them as nderure [gossipers], 'Okpo flirts petulantly, pursuing adolescent female to fulfill its sexual fantasies - with the adult approval' (Onyile 2016:49). The individual who is enacting the Oriọkpa masquerade feels that if he allows the adolescent woman to look closely at him, she may recognise him and betray his identity. This may be the reason why Onyile (2016:51) further submits that 'anonymity serves to protect the identity of the masker through the transformation process, bearing in mind that it is the mask that transforms a human into a spirit'. On sighting an adolescent girl, Oriọkpa would say: Nderure, legde m hee, olegdem ọgadghke ọngelem [gossiper, just continue looking at me. Look at me as if you are not looking at me]. This brings joy to the girls who will be running up and down, thereby taking the ceremony as an opportunity for body exercises and fitness.

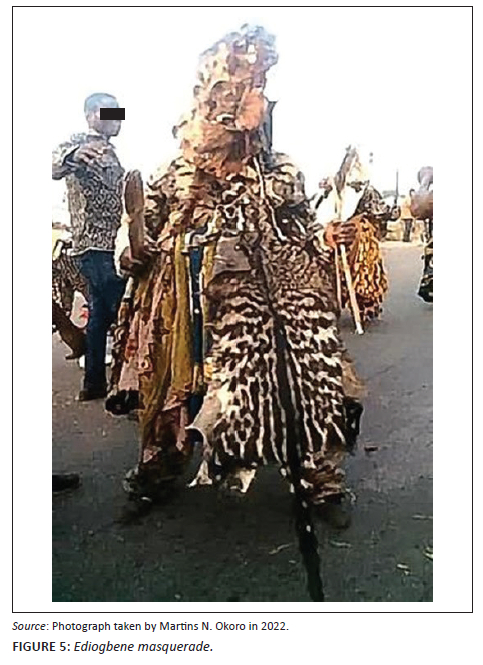

It is to be noted here that while the Oriọkpa targets and pursues adolescent girls just for beating's sake, Ediogbene (Figure 5) pursues Oriọkpa to beat as well. This makes Oriọkpa take to its heels upon sighting it. There is no clear reason for this except that it is commonly known in Nsukka that Ediogbene is stronger than Oriọkpa. This is supported by the saying that Ediogbene and Oriọkpa are not of equal strength. Also, Ediogbene would attempt to 'flog' everybody, including the elders, if the rope tied around its waistline were not yanked by an escort. This makes the entire audience unsettled. Ediogbene's costumes are made of clothes and skin derived from Ediogbene (African civet). The skin is used for making the headgear and covering the chest down to the waist, while pieces of clothes are tied around the waist. Of importance is the fact that it is the costume made from African civet skin from which the nomenclature is derived.

Ishimaa, in most cases, serve as agents of social control. They are a 'mechanism of social control, and are effective in the elimination or control of aberrant or unacceptable behaviour' (Sargent 1988). Agu (2017) reports:

[T]hey are primarily used in Nsukka traditional societies as a form of entertainment, as well as to enforce certain laws, values and discipline that needed anonymity and fastidious solutions. They are used as agents of coercion to change recalcitrant citizen, to enforce laws and customs and a security apparatus to effectively police the community. (p. 3)

In line with the above, Meek (1937) argues that the law enforcement is a masker impersonating a genius known as Ọmabe, which is sent to pillage a man's property. It is a cross-lineage and -village cult association whose functions are socially oriented, and it is an integral part of the Nsukka system of law and authority.

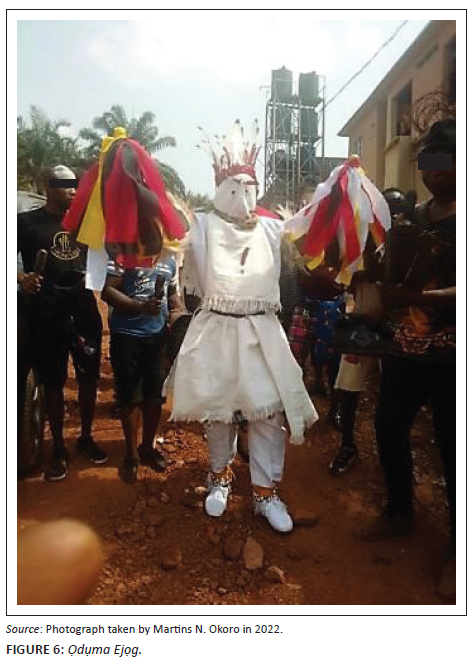

In terms of performances, Ishimaa does not employ agility and there are no flitting movements. They are the elderly masquerades whose powers, according to Aniakor (2005:18), 'derive from "bad" medicine which transform them into forbidden presence'. Often, they boast of the efficacy of their charms. They appear in different costumes. For example, Ishimaa Ọdụma Ejọg (Figure 6) appears in white ekpọtọ fabric, wearing a red cap decorated with white eagle feathers. On the mouth and chest regions are attached red feathers called Awụ. Nza ebule are attached to the two arms from the shoulders to the elbows. On both hands, it holds knives decorated with red, yellow, black and white strands of cloth. Around the ankles are tied rattles commonly called Izere and it wears a pair of white canvas shoes on its feet. Metaphorically, the meaning of Ọdụma Ejọg lies in the fact that it is beautiful, yet it fights and wins other masquerades in spiritual battles.

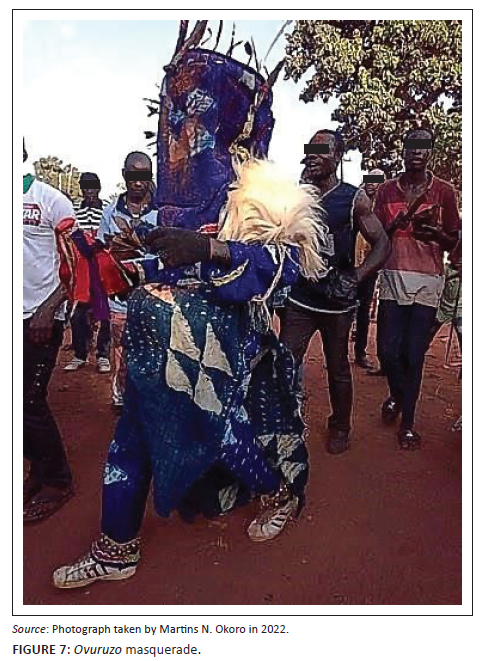

Ovuruzọ's (Figure 7) headdress is decorated with some feathers, and on its left hand an nza eble is tied between the shoulder and elbow. It holds a knife decorated with red and blue strands of cloth. It is to be stated that it speaks loquaciously and it is its garrulous and humorous nature that endears it to many people, who listen and laugh away their sorrows during its outing.

Of note is the fact that the above ritualistic masquerades are invited to perform exorcism through incantations and sacrifices with day-old chicks and eggs aimed at warding off bad spirits disturbing a person. In the middle of the night, the objects of sacrifice are dropped off at a junction of a trifurcated road to consummate the ritual.

Events in between arrival and departure of Ọmabe in Nsukka

There are other events that follow and begin on the day following the arrival of Ọmabe masquerades and are referred to as the ụtụtụ-ahọ [the morning of Ahọ market day]. After it, no other event takes place until the 16th day, when the mmaji ọnụọkachị outing, which literally means breaking of the arrow's mouth that takes place. After it, all other events occur at an interval of four days until the day of the departure of Ọmabe. These events include ashụ amgbọtọ [market for the maidens], ashụa ụla [market for departure] and ụla maa [departure of Ọmabe].

In the orderly counting of four vernacular market days in Igboland, which Nsukka is a part of, Eke comes first, followed by Orie, and then Ahọ and Nkwọ. Ụtụtụ ahọ maa is so called because, as pointed out earlier, the arrival of Ọmabe must be on the Orie market day. So if Ọmabe arrives on Orie market day, the following day, being Ahọ market day, becomes the ụtụtụ ahọ maa. On that day, there are no outings of masquerades. Instead the wooden gong called agbarada is sounded very early in the morning in order to alert natives that Ọmabe would be playing music. This makes the devotees and invitees converge on the village square. Ayogdi, which is rhythmic and has four stanzas, is played first, and the oldest man in the village (Ogbu ndidi koko) and all maskers as well as title-holders (Ibeọja) all turn up for the occasion. After that, music for healing the sick children follows. The following lyrics depict a plea for healing to a herbalist:

Herbalist, who cures blindness and other ailments, if you make my child to become well again, carry him to me, if you make my father's child to become well again, come and dance along, because I do not know which egg hatches a cock, our youths are kings who kill Elephant, and the abode of wild cat is without feathers with which medicine for a sick child is prepared!

When this particular stanza is completed, music for the land called egwu al - which involves the imaginative manipulation of words, proverbs, idioms and anecdotes - begins in earnest. It must be pointed out here that an effective music for the land is impossible without resorting to proverbs. It is rendered by a vocalist called onye ọkw'egara and played in a rhythmic synchronising order and lasts for about half an hour. When it reaches crescendo, a sudden change in the sound occurs as a folktale is introduced into the music. After this track on folktales, a track to eulogise those who have been conducting themselves well and have been leading good lives in the village is played. It has the following lyrics: 'well-behaved persons hail from our place … If a cock crows, it is an indication that the day has broken'. Finally a hot, fast and quick music track will be played while others dance to it. The intense, complicated and yet emotional and seductive music track lasts for several hours. There are also other tunes different from the aforementioned that are played based on the immediate happenings. For instance, when some men offer money before the beginning, the track played is ụmụ d'h banyị ememe anyị adeje, al'h do mene mene, meaning, 'our sons have provided for us, let the land bless them abundantly'. The Ọmabe vocalist begins by pronouncing blessings on them, saying: ijir nan safụ ebọ, me ijiri ebọ safụ etọ [if they have one, let it be doubled, and if they have two, let it be tripled]. This is a way of showing appreciation for their kind gestures. As the music is played, drinks, porridge, a type of local delicacy known as ọkpa and lumps of goat meat are served to everybody present. Of note is that the mode of sharing meat is that the provider puts a lump of meat in the recipient's mouth and cuts the outer part with a knife, and the recipient says: Ayọ m neg n'rh m [I am grateful that you are the one who gave it to me].

After the ụtụtụ ahọ maa event and performance, common 'greetings' on the lips of many people around Nsukka are in the form of the question: are you going to Orie-Nsukka? Put differently, the question is: would you attend the mmaji ọnụọkachị event which would take place on the 16th day of arrival of Ọmabe masquerades? In the evening of that day, all roads lead to the arena. People troop in. Masquerades come there in their numbers from different villages. There, Echaricha perform to the audience, comprising traditional rulers, councils of elders and title holders. They, in turn, move swiftly to the centre of the arena, leap into the air and perch on a mound in the centre of the arena, raise their hands and look skyward. The leaping is followed by several Dane gunshots into the air. This continues until dusk, when each Echaricha has taken its turn to perform, after which they head home. One needs to behold the beauty of the Echaricha as they head home at dusk. This may be the reason why revered novelist Chinua Achebe (1984) describes Echaricha's body of tiny metal discs throwing back the dying lights of dusk as a truly breath-taking experience.

The departure of the Ọ mabe spirit

On the day of Ọmabe's departure, it is incumbent on the maskers each to bring small earthenware pots called akere to the village square. They tie on them ọmụ [palm fronds] and a day-old chick. Some grains of maize and some lobes of kola-nuts are perforated and passed through the strands of these palm fronds for activation, aesthetic enhancement and enrichment. The initiated rub odo powder made from the Dracaena arborea plant on their faces. Following an explanation provided by the author's informant Okoro,7 using the grains of maize in decorating the palm fronds tied around the earthenware pots and the slaughtering of pigs is based on the saying that Onweg iye haa Ọmabe ke az'z, ọkpa ne anh eshi, which loosely translates to 'no delicacy is preferred by Ọmabe to maize, ọkpa (local delicacy) and pork'. Pork, ọkpa and maize are very essential in the departure of Ọmabe because they are its favourite comestibles.

Ọmabe plays music outside, in front of its house. The sound of the music, which becomes highly emotive, sends shivers down the spines of the listeners. It warns, advises, as well as bids farewell to the natives, making teardrops accentuate their faces. Some examples of the titles of this music are omer onye emegee [that which inflicts a person who did not offend it], ka anyi kar bu ke ọji adh [as we decree it, so shall it become], ometeru sa vuru [if you commit sacrilege, face the consequences], ọhọ ogori ne m ad'h gaa [bad luck is not my portion] and Ọmabe ladoo [farewell, Ọmabe]. After this, an egwual music track starts and reaches the crescendo before changing to ihwue (story-telling) and finally to egwuọrkh (allegretto), accordingly. As this lasts, several cannon gunshots are fired by devotees as they cheer themselves and charge the atmosphere.

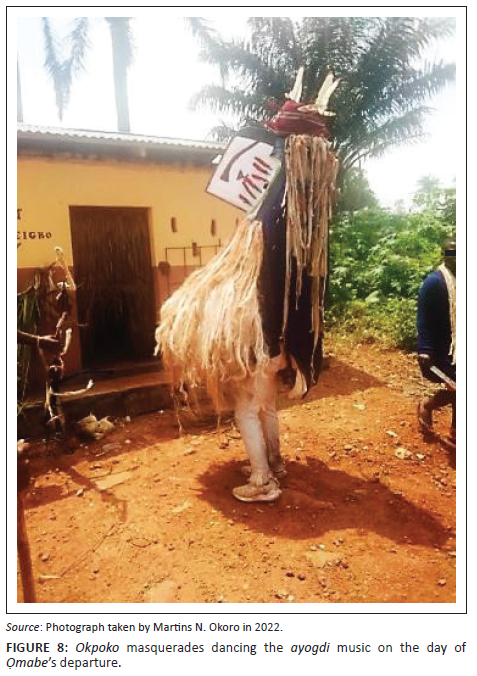

At one stage, the Okpoko masquerade (Figure 8) comes out in a company of some of its devotees, goes to the village squares where it dances the ayogdi music and is received by the elders who present kola-nuts, goats, rams and fowls. Those who have personal problems seize the ample opportunity and make supplications and vows to the masquerade. Gebe Ezema, for example, requested that if his brother who had gone to study in Japan came back successful, he would offer Ọmabe a goat. Anwurika Ezugwu, another key informant, gave Ọmabe a goat in fulfilment of a vow he had made concerning the release of his nephew, Ebuka Ezugwu, from prison.

Authenticating the potency of Ọmabe, Ugwuede8 recalled that after more than 15 years of marriage, he could not have a child, but when he made a vow to Ọmabe in that regard, during the departure, his wife later conceived and delivered a baby boy. In a subsequent Ọmabe masquerade festival, he redeemed his vow.

At dusk, the initiated are set to escort the Ọmabe spirit to Ugwu from whence it departs to the land of the ancestors, as is the belief of the Nsukka people. They carry their decorated earthenware pots and machetes in their hands as they repeatedly shout: Ugwu Adana ogbuwo ogwe, ọtr'h ọmegọ n'ije eruooo! [the Doubting Thomas, movement has begun!], eleo! eleoo! eleooo!, enwo! enwo! enwo! [lamentations]. They smack these machetes in the form of handshakes and point them towards the direction of the Ọnụ-Ọmabe, a place referred to as the mouth of Ọmabe. One after another, each of them dances to the last ayogdi or mgborogdi music. After this, the last track, known as the ọrịgwọgwọ, is played as follows: Anyị amịr'h emịwerere, nd'h nwe obodo amịr'h emịwerere, Abọshị okele amịr'h emịwerere [we have become free; those who own the town are about to be free from everything that troubles them]. While this last track is being played, the initiated shout that they are 'slippery', meaning that they have become free from problems. They proclaim their general well-being and that of their families. At this point in time, a big earthenware pot is placed on the ground for the initiated to put ritual objects representing bad lucks and ailments. After this, Ugwu Ọyịna Nwete carries the pot and leads the way to the Ugwu in company of the other initiates.

According to one informant, Ezugwu Ifeanyi, there is way of judging whether the ritual is successful or not when the Omabe returns to the spirit world of the ancestors. He explains:

'When they arrived at the place, the pots were laid beneath a particular Iroko, a totem tree of Ọmabe. Some incantations were carried out, after which a type of bird called Okpe flew out from a hole and perched on the Iroko tree, a clear sign of the successful completion of the ritual and an indication of the smooth departure of Ọmabe to the spirit world of the ancestors.' (Ezugwu Ifeanyi, 44 years old, an ardent follower of Igbo traditional religion, 19 June 2018, Nsukka)

It is at this point that the initiated, without looking back, head back home, singing the song entitled 'wὸlὸlὸ wὸlόlόlό wὸlὸlὸ wό lόlόόόό'. Upon hearing this song, their wives back home prepare buckets of water in the façade for the initiated to bathe before entering the house. Inside the house, palm oil is applied on their legs in order to ward off the Ọmabe spirit, ensuring that the safety of their households is guaranteed (Okoro 2022). One remarkable thing about this tradition is that on the following morning, there is jubilation all over the town in celebration of the successful completion of the rituals. Relatives, friends and well-wishers pay visits to the initiated and offer them gifts such as fowls, tubers of yam and other food items, expressing their happiness. Those who have become whole seize the opportunity to share testimonies.

The post-Ọmabe departure

A month after the departure of Ọmabe, the Ọnwa etọ festival starts and farmers rest. Ọnwa etọ is celebrated on the Ọzọ-Orie and Ọzọ-Ahọ days. According to the author's informant Ugwuanyi,9 every devotee performs the Igọ chi and ịgọụkwụ maa, which entail the appeasement of the personal god and legs of Ọmabe, respectively. The ritual of detaching the wooden handles from the metal parts of the hoes used for cultivation is performed inside the yam barn by farmers. They pour cooked cowpeas on the wooden parts, while thanking and appeasing Shuajiọrk - the god of farming. The separated hoe parts remain there until the next farming season, when they will be attached again for the season's cultivation. Playing of all types of cultural music such as Ikorodo, Ogwume, Adabara, Igbamangwu and Ogelle commences in order to cushion the effect of Ọmabe music. No other type of music is played during the stay of Ọmabe in the land.

The high point of Ọnwa etọ is the outings of the Okpoko, Ajaka, and Ikejiọkwọ masquerades, collectively referred to as, in this instance, the Egbe-ochal [the kite that watches over the land]. They move around the villages and lay curses on persons who have used diabolical means to enchant natives. Okoro10 recounted to the author how he was poisoned through kola-nut by a certain woman, and the Ikejiọkwọ masquerade was invited to his house at midnight and it rained curses on her. Within seven native weeks, the woman made an open confession that she was the one responsible for the kola-nut poisoning. People in the village avoided and shunned her and her son died of a fatal motorcycle accident. It was believed that the fatal accident was a form of punishment for the woman.

The arrival of Egbe-ochal makes it possible for the Oriọkpa masquerade to come out and discipline those who commit crimes, using strokes of a cane. It also goes to the homes of 'stiff-necked' individuals who refuse to participate in communal works and pillages their valuable belongings.

Conclusion

This study focused on the Ọmabe cultural heritage festival among the Nsukka Igbo people. It emphasises the rituals, materiality, its performance and artistic components through the lens of ethno-aesthetics, therapy and healing. From the above discussion, the overall picture that emerges is that the Nsukka Ọmabe cultural festival has immense benefits, given the fact that Ọmabe relates spectacularly with Nsukka society and in so doing provides therapy to the depressed, heals the sick and performs exorcisms. The social and cultural significance of Ọmabe festival lies in the fact that it is a source of entertainment through which the way of life and identity of the people are showcased to the neighbouring towns. What is established in this study is best described in an Igbo adage which says that a town uses what it has towards solving its problems and that a peoples' endowment is their strength. It is in line with this adage that a masquerade festival such as the Ọmabe that involves rituals and theatre is employed by the followers of indigenous religion in Nsukka Igbo for their general well-being.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to late Chief Gabriel Chukwuma Okoro, Ifeanyi Ezugwu, Ibe Nwadaka, Chukwudi Ugwuanyi and Emeke Ugwuede for the rich ideas they gave him in the course of oral interviews with them. These ideas undoubtedly enriched the author's knowledge regarding the Ọmabe festival.

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

Author's contributions

M.N.O. is the sole author of this research article.

Ethical considerations

This article followed all ethical standards for research.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the author.

References

Achebe, C., 1984, 'Foreword: The Igbo world and its art', in H.H. Cole (ed.), Igbo arts: Community and cosmos, pp. xi-xii, Museum of Cultural History, University of California, Los Angeles, CA. [ Links ]

Agbo, P.O., Opata, C.C. & Okwueze, M., 2022, 'Environmental determination of names: A study of Úgwú and naming among the Nsukka-Igbo people of Nigeria', HTS Teologiese Studies/ Theological Studies 78(3), a6977. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v78i3.6977 [ Links ]

Agu, A., 2017, 'Sanitizing Nsukka cultural values', Ideke News Letter 4(1), 3-4. [ Links ]

Amankulo, J., 2002, 'The art of dramatic art in Igboland', in G.E.K. Ofomata (ed.), A survey of the Igbo Nation, pp. 399-412, Africana First Publishers Ltd, Onitsha. [ Links ]

Aniakor, C., 2005, Reflective essays on art & art history, Pan-African Circle of Artists Press, Enugu. [ Links ]

Aniakor, C., 2012, 'Global changes in Africa and indigenous knowledge: Towards its interrogation and contestations', in S.C. Onuigbo (ed.), Indigenous knowledge and global challenges in Africa: History, concepts and logic, pp. 55-108, Institute of African Studies, University of Nigeria, Nsukka. [ Links ]

Aniakor, C.C., 1976, 'The Ọmabẹ cult and masking tradition', in G.E.K. Ofomata (ed.), The Nsukka environment, pp. 286-306, Fourth Dimension Publishers Ltd, Abuja. [ Links ]

Aniakor, C.C., 1988, 'Igbo plastic and decorative arts', Nsukka Journal of the Humanities 3(4), 1-35. [ Links ]

Aniakor, C.C., 2002, 'Art in the Culture of Igboland', in G.E.K. Ofomata (ed.), A survey of the Igbo Nation, pp. 300-348, Africana First Publishers Limited, Onitsha. [ Links ]

Asogwa, I. & Duniya, G., 2017, 'Flexibility of approach in art practice as research: Hints in Omabe based sculpture installations', Mgbakoigba, Journal of African Studies 6(2), 79-100. [ Links ]

Asogwa, O. & Odoh, G., 2022, 'Problemitizing the dominant narrative on women's involvement in Igbo masking tradition', Journal of Asian and African Studies. https://doi.org/10.1177/00219096221079333 [ Links ]

Cole, H. & Aniakor, C.C., 1984, Igbo arts: Community and cosmos, Museum of Cultural History, Los Angeles, CA. [ Links ]

Drewal, H.J., 1974, 'Gelede masquerade: Imagery and motif', African Arts 7(4), 8-96. https://doi.org/10.2307/3334883 [ Links ]

Fosu, K., 1986, Twentieth century art of Africa, Gaskiya, Zaria. [ Links ]

Gore, C., 2008, 'Burn the mmonwu: Contradictions and contestations in masquerade performance in Uga, Anambra State in Southeastern Nigeria', African Arts 41(4), 60-73. https://doi.org/10.1162/afar.2008.41.4.60 [ Links ]

Ikwuemesi, K. & Onwuegbuna, I., 2017, 'Creativity in calamity: Igbo funeral as interface of visuality and performance', Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies 32(2), 184-200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312-2017.1391176 [ Links ]

Kalu, O.U., 2002, 'Igbo traditional religious system', in G.E.K. Ofomata (ed.), A survey of the Igbo Nation, pp. 350-366, Africana First Publishers Limited, Onitsha. [ Links ]

Meek, C.K., 1937, Law and authority in a Nigerian tribe: A study in indirect rule, Barnes and Noble, London. [ Links ]

Ngele, O.K., Uwaegbute, K.I., Odo, D. & Agbo, P.O., 2017, 'Soteria [salvation] in Christianity and Ụbandu [wholeness] in Igbo traditional religion: Towards a renewed understanding', HTS Teologiese Studies/ Theological Studies 73(3), a4639. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v73i3.4639 [ Links ]

Nwoko, S., 1989, 'Omabe masquerade tradition in Ibagwa-Aka: A resource for visual communication design', master's thesis, Departement of Fine and Applied Arts, University of Nigeria. [ Links ]

Okoro, M., 2022, 'Women in the culture of Igboland: Extrapolations from Nsukka, south-eastern Nigeria', Asian Women 38(1), 77-106. https://doi.org/10.14431/aw.2022.3.38.1.77 [ Links ]

Onyile, B.O., 2016, 'The materiality of cement in the cultural matrix of the middle Cross River region', African Art 49(3), 48-60. https://doi.org/10.1162/AFAR_a_00298 [ Links ]

Opata, C.C. & Apeh, A., 2018, 'In search of honour: Eya ebule as a legacy of Igbo resistance and food security from World War II', International Journal of Intangible Heritage 13, 114-127. [ Links ]

Opata, C.C., Apeh, A., Amaechi, C.M. & Eze, H.O., 2021, 'A woman can become a "man": Rituals and gender equality among the Nsukka Igbo of south-eastern Nigeria', The Journal of Intangible Heritage 16, 64-75. [ Links ]

Sargent, R.A., 1988, 'Igala masks: Dynastic history and face of the nation', West African Mask and Cultural System 126, 17-44. [ Links ]

Ugwu, C., 2011, 'Social change and Ọmabe: A critical ethnography', Nsukka Journal of Humanity 19, 112-119. [ Links ]

Ugwu, I., 2013, 'Traditional Nigerian theatre, ideology and the national question: Igbo masquerade and folk tale performance as example', Ikenga: International Journal of the Institute of African Studies, University of Nigeria, Nsukka 15(1&2), 18-32. [ Links ]

Uwagbute, K., 2021, 'Christianity and masquerade practice among the youths in Nsukka, Nigeria', African Studies 80(1), 40-59. https://doi.org/10.1080/00020184.2021.1886049 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Martins Okoro

martins.okoro@unn.edu.ng

Received: 15 July 2022

Accepted: 31 Aug. 2022

Published: 20 Dec. 2022

1 . The Nsukka peoples' belief is that once a woman has taken the Ọyimaa title, she automatically ceases to be a woman and has become a 'man', in that all the Omabe secrets are revealed and opened to her. For further insight, see Opata et al. (2021:64-75).

2 . Interview conducted on 21 January 2022 with Ifeanyi Ezugwu, a 44-year-old Ọmabe devotee and masker.

3 . Interview conducted on 25 January 2022 with Ibe Nwadaka, a 40-year-old follower of Igbo traditional religion.

4 . Interview conducted on 23 January 2022 with Anayo Ozioko, a 45-year-old follower of Igbo traditional religion.

5 . In Igboland, Ugwu is referred to as a mountain. It is given to male children as a name. For more insight on Úgwú, see Agbo et al. (2022).

6 . Interview conducted on 11 March 2015 with Chukwuma Okoro, an 82-year-old custodian of Nsukka's culture and tradition.

7 . Interview conducted on 11 March 2015 with Chukwuma Okoro, an 82-year-old custodian of Nsukka's culture and tradition.

8 . Interview conducted on 18 June 2022 with Emeke Ugwuede, a 50-year-old Ọmabe devotee and masker.

9 . Interview conducted on 12 May 2022 with Chukwudi Ugwanyi, a 55-year-old follower of Igbo traditional religion.

10 . Interview conducted on 11 March 2015 with Chukwuma Okoro, an 82-year-old custodian of Nsukka's culture and tradition.