Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

HTS Theological Studies

On-line version ISSN 2072-8050

Print version ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.78 n.1 Pretoria 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v78i1.7232

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Online theological education within the South African context

Johannes J. Knoetze

Department of Practical Theology and Mission Studies, Faculty of Theology and Religion, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

This article presents the results of an empirical research study conducted at the Faculty of Theology and Religion at the University of Pretoria on students' experiences of online theological education during the outbreak of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic between 2019 and 2020. Particular attention is given to the context of higher education in South Africa as a background to the research. The article discusses students' views and experiences of the different modes of teaching, namely, face-to-face, online, and hybrid or blended teaching. After discussing the different modes of teaching, some of the challenges experienced in online learning are explored, and finally, several recommendations are proposed for the improvement of theological education. The article concludes with the finding that the current infrastructure in South Africa is sufficient to make online education sustainable. Within the present South African context, it might also be the only viable option to ensure access to higher education for students. The study also found that the current theological students prefer online or at least blended methods of theological education for different reasons mentioned in the article.

CONTRIBUTION: Although there are still some challenges to online theological education, the current infrastructure in South Africa is sufficient to make online education sustainable. The article promotes multi-, inter-, and transdisciplinary aspects of studies in the international theological arena.

Keywords: higher education in South Africa; online education; theological education; National Student Financial Aid Scheme (NSFAS); COVID-19.

Introduction

The author of this article conducted the same research at two different universities in South Africa, hosting a theological faculty. In 2019, the research was carried out at the North-West University (NWU) as part of a Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL) research project from which several articles from the team of researchers were published. With the approval of the research team at NWU, some contextual changes were made to the research questionnaire. The same questionnaire was used in 2020 at the Faculty of Theology and Religion at the University of Pretoria (UP). In the current context of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the research regarding online higher education (HE), specifically online theological education, became paramount in the (South) African context. The article reference to the broader HE has to do with the place of theological education at higher education institutions (HEIs) in South Africa against the socio-economic and political South African context (Knoetze 2020a). This study aims to determine whether the (South) African HE landscape is equipped for online theological education.

Methodology of this research

The questionnaires were electronically distributed through Google Forms, and the whole research project was conducted in a virtual environment. A purposeful sampling procedure was employed during the qualitative phase of this study, ensuring the selection of information-rich cases where the researcher determined the characteristics of the participants (Johnson & Christensen 2017). For the quantitative phase, a multistage cluster sampling procedure was utilised. A cluster sampling method, specifically multistage cluster sampling, involves the selection of respondents in naturally occurring groups existing in two or more levels or clusters to ensure sufficient representation of the target population (McMillan & Schumacher 2010). As part of the statistical analysis of this study, the researcher included both descriptive and inferential statistics for the quantitative phase and thematic analysis for the qualitative phase. The quantitative phase consisted of descriptive statistics where frequency analysis was carried out. Firstly, for the inferential statistics, initial tests confirming the validity and reliability of the data collection instrument were conducted before data analysis. These tests included exploratory factor analysis (EFA) testing construct validity, followed by a Cronbach alpha test ensuring reliability (Devlin 2018). Secondly, statistical assumption tests of normality and homoscedasticity were conducted to ensure that all the underlying statistical assumptions were met prior to data analysis (Garson 2012). Thirdly, inferential statistics in testing the hypotheses were conducted inclusive of correlation analysis and analysis of variance (ANOVA). Fourthly, post hoc and magnitude of effect sizes were reported for educational and practical implications (Allen 2017). During the qualitative phase, thematic analysis procedures were employed to analyse the interview data to gain an in-depth understanding of the views and opinions of the participants.

Background

Theological education at South African universities is built on centuries of intellectual and experiential knowledge. At present, these must be attained in a complex and interconnected world, in general, and embedded as a role player in the academic offering of ecumenical theological faculties at state-owned institutions in a post-apartheid and, in many instances, a post-Christendom country. In addition, the fact that Africa is a continent struggling with the effects of colonisation and decolonisation also has to be considered.

In this context, theological education at HEIs aims to continue with teaching and learning that is of good academic quality, transformative, contextual, relevant, decolonised, Africanised and inclusive. Some of the priorities of theological faculties, in line with all HE disciplines, include student access and success, completion of academic programmes within minimum time and employability. It is exactly these priorities that force theological faculties to take new initiatives to broaden the access possibilities, develop multifaceted academic programmes and teaching strategies, with possibilities of different delivery modes, and develop a curriculum for students studying theology to be able to have access to multiple career options in order to address the issues of employability. To make theological education at NWU more accessible, online and hybrid modes of teaching have started around 2016 through the Centre for Open Distance Learning at NWU. Currently, the largest percentage of theological students at the Faculty of Theology at NWU studies is through the Centre for Open Distance Learning (ODL).

With the increasing number of theological students from previously disadvantaged populations and denominations, faculties of theology continue to impact a disillusioned and demotivated South African society. As such, theological faculties must continue to develop hybrid or blended learning methods with a more significant effort and emphasis on the use of technology. These matters are not all new to the teaching activities within any theological faculty, as indicated with the Faculty of Theology at NWU. However, what makes the situation different is the planning for teaching and learning in a new paradigm where COVID-19 has forced faculties to work entirely within the framework of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) and maybe even beyond. This 4IR framework has emphasised the need for considering new modes and methods of teaching, learning and assessment. In this regard, the faculties of theology and HE are making headway into a new direction characterised by new teaching and learning challenges.

This line of thinking informed the consideration of and planning about a dynamic, reliable, and appropriate online teaching, learning and assessment approach and strategy. It should be justified and shaped by the requirements of HE, principles of attainable excellence, and high impact teaching and learning practices linked to essential learning outcomes. Another very important role player is the churches who send their students to the different faculties. Are the different churches prepared for theological training that is exclusively online, or do they expect more of the faculties of theology?

While all this is part of the reality, the other part of the reality is the socio-economic context within South Africa, which will be discussed in the following subsection.

The South African context and higher education

Socio-economic context

Early in 2019, the World Bank reported that South Africa is the most economically unequal country in the world. This inequality now seems to be more noticeable than in 1994 when it became a democratic country (Scott 2019:np). The same report also stated that since the African National Congress (ANC) came into power, great strides have been made in providing basic services such as water, electricity, health services, and education. However, 25.2% of the country's population lives below the food poverty line (with less than $37 a month), while more than half of the population (55.5%) is living in poverty (with less than $83 a month). The income of the different population groups in South Africa is illustrated in Figure 1.

On 24 August 2021, a new record unemployment rate of 34.4% was reported in South Africa. If an expanded definition of unemployment (including those who are discouraged in seeking work) is used, the rate of unemployment would rise to 44.4%.

Turning to the social context for a moment, it is important to note the family decay in the South African context pointed out by Freeks (2020). Freeks (2020:192) indicated that the number of orphaned children in South Africa increased by 13% from 2012 to 2013, equating to around 380 000 new orphans. In his discussion he mentions that these children are more likely to be absent from school for a number of reasons, such as food insecurity, anxiety, and depression. Furthermore, the lack of healthy mentorship to emerging adults becomes clear in light of the fact that 46% of all children aged 15+ years in South Africa have grown up in child-headed households.

With these few socio-economic statistics, the question arises as to what is the contribution of theological education, and for that matter HE, to the socio-economic realities of South Africa, if any? While this is not the focus of this article, it is important to take note of Knoetze's (2020a) publication titled 'Transforming theological education is not the accumulation of knowledge, but the development of consciousness'. A second question that arises from the socio-economic context is as follows: In a society where there are very few male mentors, what is the importance of mentorship for theological students at HEIs? This relates closely to the expectations of the different churches. A third question arising is: How is it possible to give more people who qualify access to HE? The following section will discuss the South African government aid to help students overcome financial constraints.

Higher education and National Student Financial Aid Scheme

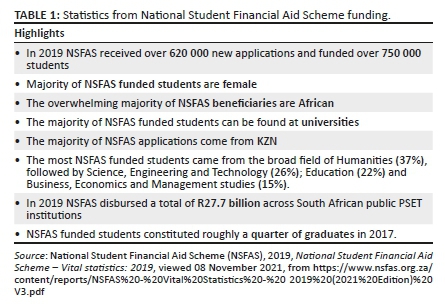

The National Student Financial Aid Scheme (NSFAS) has a clear social mission - to help disadvantaged students who are academically qualified, gain admission to post school education and training (PSET). Accordingly, all students who come from a household with an annual income of less than R350 000, may apply for the financial assistance under this scheme (NSFAS 2019:8). In 2019, 104 538 students from households receiving social grants were financially assisted by the NSFAS (NSFAS 2019:10); some further highlights are noted in Table 1.

With the focus of this article on theological education, the most important information from the above statistics is that 37% of the NSFAS funding goes to the broader field of Humanities, which includes Theology. From the NSFAS report on the percentage of graduates (2017) that were NSFAS funded students only, two universities hosting a faculty of theology is mentioned, namely Stellenbosch University (5.9% NSFAS graduates) and UP (10.4% NSFAS graduates), while the NSFAS students made a much more significant portion of graduates at other universities, for example, University of Zululand (77.4% NSFAS graduates) and University of Mpumalanga (85.2% NSFAS graduates). From the research conducted at the two theological faculties, 60% of the students indicated that they received no financial support from their churches or denominations. At UP's Faculty of Theology and Religion, only 2.67% of the undergraduate students for 2020 were NSFAS students, while at the NWU, which can be viewed as 'more rural' with its one campus in Mahikeng, 42% of the undergraduate students at the Faculty of Theology were studying through NSFAS.

Although there is an increase in the number of undergraduate students of theological faculties benefitting from NSFAS, the above statistics show that it is not only theological faculties which are dependent on NSFAS. However, with the focus of this article on online theological education, it is also important to look at the South African context regarding the usage of internet.

Internet use in South Africa

The following information on the usage of internet in South Africa is taken from Kemp (2021). He indicates that 62% of Southern Africa's population are internet users. Although it is the highest rate of internet use when compared with the different regions of Africa (Western Africa - 42%, Eastern Africa - 24%, Northern Africa - 56% and Central Africa - 26%), it is still the lowest in the world. Except for Africa, only Southern Asia (42%) and Central Asia (57%) have a lower data usage. However, when comparing the mobile phone connections with the Southern African population, it is 163% in relation to the population.

The population of South Africa is about 59.67 million people, of which 67.6% are urbanised. The median age of the South African population is 27.7 years, and the adult (15+ years of age) literacy rate is 87%. There are 100.6 million mobile phone connections and 38.19 million (64%) internet users in South Africa. Of this, 64% of the average daily time spent on the internet by people between 16 and 64 years of age equals 10 hours and 6 minutes, and 94.6% access the internet via mobile phones. Of the internet users between 16 and 64 years of age, 98.2% own a mobile phone and 85.4% own a laptop or desktop computer. Because the focus here is on HE, the article mentions the following statistics of December 2020 from the UNISA website, the biggest distance education university in Africa, regarding HE: Total visits 15.4 million, unique visits 2.19 million, average time spent per visit 10 minutes 47 seconds, average pages per visit is 7.78. Unfortunately, other South African universities are not mentioned.

Looking at the above statistics and trying to draw some lines between the socio-economic, the NSFAS and the digital data, there are some remarkable comparisons. For example, the unemployment rate is 34.4% - 44.4%, while 64% of the population are internet users. In the author's research among the theological students at the two aforementioned faculties, 69.6% indicated that they have regular or easy access to an electronic device (smartphone, tablet, or laptop), while in the same group only 47.4% indicated they have easy or regular access to the internet. Although it was not a pertinent question, the easy or regular access to internet may be because of the free internet available 24/7 on those campuses (see Knoetze 2020b:63).

Online theological education

The COVID-19 pandemic 'forced' all HEIs to work online, which is also true of the theological faculties. However, it must be stated that it seems as if the theological faculties made a good transition from face-to-face teaching to online classes. The undergraduate pass rate of the Faculty of Theology and Religion at UP clearly shows a decline in the recent years. In 2019, when there were face-to-face classes, the pass rate was 85.5%, while in 2020 it declined to 83.1% as a result of the 'forced shift' from face to face to online classes during the 'hard lockdown' in South Africa. Then, in 2021, there was still another drop in the pass rate to 81.9%. However, online classes seem to have become the new 'normal'. A noteworthy fact is that the biggest drop in pass rate was reported in the Department of Practical Theology and Mission Studies: 2019 = 87.1%, 2020 = 86.6%, and 2021 = 73.3%.

Interestingly, one of the students responded in the questionnaire as follows:

[I] feel like modules such as practical theology need to be done in person and that doing them online has deprived us of the opportunity of feeling like future missionaries and teachers.

However, this steep decline in the pass rate might be because of not only the online classes but also the change in the personnel when two of the senior academics transferred to other universities, as well as a new curriculum that was introduced. With these facts in mind, we might ask whether the churches will accept only online theological education. This immediately hints at the important relationship between faculties of theology and the church because online theological education might be acceptable if the church partners with the faculty to confirm the application of the taught theology. Unfortunately, the author could not compare this with the Faculty of Theology at the NWU because they had a large contingent of online students even before COVID-19.

Other theological institutions like the South African Theological Seminary (SATS) have no contact classes and make use of what Smith (2021) calls the 'ODEL model', meaning open, distance and e-learning. Smith (2021:135) argues for the effectiveness of e-learning (online learning) based on two principles. Firstly, online teaching requires active student-centred learning, because teachers cover five times the amount of work in the same amount of time. Secondly, online teaching enables all students to engage equally because a few talkative students cannot dominate the class as in face-to-face learning.

What did the students say?

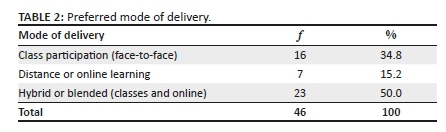

The participants shared their views regarding the preferred mode of delivery for studying at the Faculty of Theology and Religion at UP (see Table 2). However, this question was not asked at the NWU; thus, no comparison could be made.

Although many students (34.8%) still prefer face-to-face learning, it is also clear that most of the students have made a mind shift to online learning (15.2%) and the hybrid or blended method of learning (50%).

Instead of just working with the statistics, the students' motivations for the different modes of delivery are also considered. Verbatim quotes are provided below in bulleted form to reflect the students' responses to the questionnaires. Because the author received the statistics and the comments in a report format, he included only the comments that were relevant. Some comments referring to the mode of delivery were unclear, so these were excluded.

Face-to-face contact classes

-

'As a second-year student, I've experienced 6 weeks on campus in 2020 and I miss it so so much. Not only the socializing but also actually knowing your professors in person'.

-

'Because it is quite more fun when you do it in person than using an electronic device'.

-

'Class interactions are better compared to online classes. Yes, online classes come with the advantage of being able to access the class at a later stage. I find online classes demotivating. And it's easier to learn in an environment that is full of people who have different opinions and perspectives'.

-

'I find that I learn better when I am in class, and I can see and ask questions to the lecturer. Online learning does not create the learning environment as it has many challenges like technical challenges'.

-

'I personally prefer physical classes so that I can ask questions and be able to engage with the lecturer'.

-

'I wanted to come to Tuks for the student life and experience. I do not want to study from home'.

-

'In face to face we have opportunity to discuss important question and get opportunity to ask question while online we find [it] difficult to access class due to expensive of data and connection issues'.

-

'It is a great experience to be able to talk to the lecturers' face to face, interact physically, the learning materials become easy to understand'.

-

'It is more interactive and easier to communicate with your professors. It also helps to talk with your fellow students on certain theological concepts after class so that you have a better grip on it. There are also no distractions like there is at home'.

-

'The current distance learning has created an impossible standard for students. We are expected to do much more and we also have no tolerance from lecturers as there is a distance between us and them'.

-

'The faculty gives one a burning desire to interact and therefore this is mostly very difficult in online or in distance since we face many internet connection challenges'.

-

'There is more content and meaning to the things I am taught than online where I feel like there is no connection between me and the lecturer'.

-

'We are currently doing online learning and I do not enjoy it at all. It is very hard, and it sometimes feels like it's not personal at all. I miss campus. The internet makes it very hard as well as I regularly have connection issues'.

Preliminary conclusions

The first and foremost advantage of face-to-face learning mentioned by the students is that it helps to build a personal relationship with the lecturer. Thinking back to his studies and listening to the students' viewpoints, the author articulates that it has to do with the role modelling of lecturers and their mentoring. Relating to the absence of role models mentioned above, this is an essential factor. The second advantage of face-to-face learning is the factor of 'belonging'. The interactions, relations, and debates all contribute to the fact that students belong to and are part of a specific group, including a specific ecumenical group, which is very important for societal relations. The third advantage has to do with the holistic development of students. Higher education institutions must develop students not only academically but also holistically as persons, learning the 'soft skills' of life, such as living with and taking responsibility for a budget (economics), taking care of their own body (participating in sport on different levels), acquiring the skills of leadership, conflict management and many more social skills.

Accessing online classes may be difficult because of unfavourable conditions at home. These may include numerous distractions, lack of internet connectivity, or slow internet speed.

Online teaching

-

'Because it gives me the flexibility to create my own schedule'.

-

'Because it saves petrol'.

-

'Because it's like the lecture[r] is teaching only you in the online platform. Plus it saves money and time for those who travel'.

-

'I am scared of getting COVID and I have adjusted to this new at-home life'.

-

'I feel that it makes things easier for us as students, there is not a minute wasted to get to and from classes. You have more time in a day to get things done and it also provides an opportunity for many students to work and have an income while they are studying'.

-

'It is more convenient when studying and working at the same time'.

-

'It's convenient and easy to focus, no pressure and no late classes especially with 7:30 classes. [A]nd we can always go through recordings when we miss or if the class is not convenient'.

-

'Saves us from COVID-19'.

-

'Some classes are better online'.

-

'This is because I am currently running a branch which takes away my time and I do not usually get time to attend'.

Preliminary conclusions

According to the students' comments, the positive motivation for online classes has mostly to do with the following factors: flexibility, affordability and accessibility. Another important motivation is the lowering of the risk of getting infected with COVID-19.

Hybrid or blended teaching (face-to-face classes and online)

-

'Contact classes allow students to actively participate and engage with the course material and other students. However, I believe that online classes give students more time to actually get their work and studying done without having to spend hours going back and forth to classes. So a balance between the two would cater for students who prefer contact learning and those who prefer online learning'.

-

'COVID-19 has forced many of us to go online which has not been entirely negative as I get to work at my own pace and produce good or "excellent" and to add face-to-face contact it would be an equal balance of seeing other students and get to have more effective communication. These would be the perfect balance'.

-

'Face to face I might get more understanding and online recorded sessions I understand and get more information'.

-

'I like the flexibility of online, but it would be nice to also incorporate face to face classes for a much more authentic experience where we can all engage as scholars'.

-

'It is because of the world is changing we have to learn both ways not because its a need for us to do things online. They must learn the online way so that people can adapt to both learning'.

-

'It's difficult to remember how fully in person classes work and thus a hybrid provides best of both worlds'.

-

'Some theory may be more sensibly presented online to "memorize" at one's own pace. Debates and discussions, however (even if less frequently) may best be accommodated face to face'.

-

'The hybrid view I believe will give more people access to university, example two groups, A = 150 people, B = 120 people, then the university can have online and face to face classes'.

-

'This is difficult because it depends on the type of module. I prefer that the structure of modules be set up for distance learning but that core concepts be discussed in class. Face to face classes are more equipped to provide administrative information and answer questions'.

Preliminary conclusions

The most important motivation for students to choose the hybrid or blended method is the fact of being an inclusive method to help students experience the benefits of both face-to-face and online methods of learning. The second advantage of this method is that it teaches students 'formal electronic communication' skills which they will need to survive in the 4IR. Finally, this method also caters for different student personalities, learning styles, and abilities.

(South) African challenges to online theological education

The author agrees with Smith (2021:139-141) when he states the following challenges to online theological education in South Africa. The first challenge has to do with the national infrastructure. This includes matters like load shedding, or the total lack of electricity, and the affordability and bandwidth of data. The second challenge has to do with the readiness of faculties and students. Most theological faculties (and HEIs) were forced to switch to online education as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although theological faculties went to extremes to be able to conduct online teaching, and they must be complimented for what they achieved, it needs to be acknowledged that they still have a long way to go to exhaust all the possibilities of online education. This includes equipping relevant venues for hybrid or blended learning, (re)training of lecturers on the principles of online education, as well as training or preparing students for online education. The third challenge is to develop online education that is fit for the context of (South) Africa, for example, to develop and present text-based online education that do not require high bandwidth from students. The fourth challenge for online theological education is to make it accessible for the many pastors who have no official theological training either by choice, or because of a lack of resources, or the lack of opportunities. How do we bridge the gap between those who have technology and those who do not? The fifth challenge for online theological education at HEIs is the way these institutions are run as a corporate company, where students are seen as 'clients' and resources to be pursued (Botha 2011).

Recommendations

It is a fact that the world, which includes the world of HE, will never return to what it was before COVID-19. Similarly, the church will not be able to continue as it did before COVID-19. With this in mind, it is clear that we will have to redefine how we learn, teach and practise theology. It is the author's conviction that online teaching will become more and more the normal way of teaching rather than residential education for the following obvious reasons: flexibility, economic feasibility (the exorbitant cost of residential education), limited space of HEIs to accommodate all potential students as residential students, the 4IR, and so on. This immediately foregrounds the question of spiritual formation within theological education. Although this discussion is not within the scope of this article and will be dealt with in a separate article, it is worth mentioning here that online theological education creates wonderful opportunities for spiritual formation, especially when the local church and the theological faculty partner together in this regard (Smith 2021).

Considering the research, the following is recommended for theological faculties at HEIs. Firstly, the researcher is of the opinion that it is to the benefit of the church as well as individual denominations to study theology at HEIs. This will ensure academic standards as well as expand the theological discipline into other academic disciplines. It will also support and enhance theological education to keep up with online educational methods and strategies. Secondly, for churches who want to be contextual, it is necessary to expose their students not only to 'denominational' theology but also to 'academic' theology to empower them to (re)discover their own theological identity. In this regard, churches will have to partner with faculties of theology to enhance the spiritual formation of their students. Thirdly, to make online theological education more accessible, it is proposed that churches help students with proper infrastructure by making their own assets (like internet, electricity and electronic equipment) available to students, especially in marginalised rural areas. With the help of churches, the socio-economic and educational gap between students can be bridged.

Conclusion

This research study concluded with the finding that although there are still some challenges to online theological education, the current infrastructure in South Africa is sufficient to make online education sustainable. Within the current South African context, it might also be the only way to ensure access to higher education for students. It is also clear that current theological students prefer online or at least blended methods of theological education for the different reasons already mentioned in the article.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks and acknowledges Dr Mariette Fourie from NWU who carried out the statistical analysis of the empirical research and the data used in this article.

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

Author's contributions

J.J.K is the sole author of this article.

Ethical considerations

Approval to conduct this study was obtained from the Research Ethics commitee of the Faculty of Theology and Religion, University of Pretoria. No. T021/21.

Funding information

This research work received Research Development Programme funds from the University of Pretoria.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the affiliated agency of the author.

References

Allen, M., 2017, The Sage encyclopedia of communication research methods, vols. 1-4, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA. [ Links ]

Botha, N., 2011, 'Living at the edge of empire: Can Christianity prevail and be effective? A theological response to the historical struggle between empire and Christianity', Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae 37(Supplement), 133-155. [ Links ]

Devlin, A.S., 2018, The research experience. Planning, conducting, and reporting research, Sage, Los Angeles, CA. [ Links ]

Freeks, F.E., 2020, 'Community engagement addressing powers, inequalities and vulnerabilities: A missional approach', in J.J. Knoetze & V. Kozhuharov (eds.), Powers, inequalities and vulnerabilities: Impact of globalisation on children, youth and families and on the mission of the church, Reformed Theology in Africa Series, vol. 4, pp. 187-207, AOSIS, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Garson, G.D., 2012, Testing statistical assumptions, North Carolina State University, School of Public and International Affairs, G. David Garson and Statistical Associates Publishing, Asheboro. [ Links ]

Johnson, R.B. & Christensen, L., 2017, Educational research. Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches, 6th edn., Sage, Washington, DC. [ Links ]

Kemp, S., 2021, Digital 2021: South Africa, viewed 16 September 2021, from https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2021-south-africa. [ Links ]

Knoetze, J.J., 2020a, 'Transforming theological education is not the accumulation of knowledge, but the development of consciousness', Verbum et Ecclesia 41(1), a2075. https://doi.org/10.4102/ve.v41i1.2075 [ Links ]

Knoetze, J.J., 2020b, 'Christ-connected discipleship as comfort in a globalised world with a fear of missing out', in J.J. Knoetze & V. Kozhuharov (eds.), Powers, inequalities and vulnerabilities: Impact of globalisation on children, youth and families and on the mission of the church, Reformed Theology in Africa Series, vol. 4, pp. 57-73, AOSIS, Cape Town. [ Links ]

McMillan, J.H. & Schumacher, S., 2010, Research in education. Evidence-based inquiry, 7th edn., Pearson Education, Boston, MA. [ Links ]

National Student Financial Aid Scheme (NSFAS), 2019, National Student Financial Aid Scheme - Vital statistics: 2019, viewed 08 November 2021, from https://www.nsfas.org.za/content/reports/NSFAS%20-%20Vital%20Statistics%20-%202019%20(2021%20Edition)%20V3.pdf. [ Links ]

Scott, K., 2019, 'South Africa is the world's most unequal country. 25 years of democracy has failed to bridge the divide', CNN, 10 May, viewed 16 September 2021, from https://edition.cnn.com/2019/05/07/africa/south-africa-elections-inequality-intl/index.html. [ Links ]

Smith, K.G., 2021, 'E-learning for Africa: The relevance of ODEL methods for theological education in Africa', in J.J. Knoetze & A.R. Brunsdon (eds.), A critical engagement with theological education in Africa: A South African perspective, Reformed Theology in Africa Series, AOSIS, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Johannes Knoetze

johannes.knoetze@up.ac.za

Received: 17 Nov. 2021

Accepted: 11 Dec. 2021

Published: 09 Mar. 2022