Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

HTS Theological Studies

versión On-line ISSN 2072-8050

versión impresa ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.77 no.4 Pretoria 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v77i4.6482

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Dignity, justice and community as a baseline for re-interpreting being church in a Corona-defined world

Marinda van NiekerkI, II

ICentre for Faith and Community (CFC), Faculty of Theology and Religion, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

IIPEN (Participate Empower Navigate), Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

This article is written as a reflection on the relevance of being church in a world defined by the coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19). The reflections are done by listening to the stories and experiences of vulnerable men and women who were displaced from their areas of living on the streets into (mostly) temporary shelters. Different organisations, state entities, universities and churches collaborated to serve vulnerable people with dignity. Wonderful and tragic stories played out during this time. Corruption and misuse of power played out alongside passionate and sacrificial work being done by professionals and volunteers alike. This mixed package of care helped the author to reflect on the embodiment of faith and on being church. The value of collaboration is unpacked, and parts of a visual journal are used to bring the stories of people closer. Lessons learned include a growing understanding of the context of homeless people, the contributions they made to the learning experience, and the re-interpretation of critical elements of being church and what can contribute to becoming church in a just and dignified way. The re-interpretation of prayer, discipleship, missional focus, stewardship and leadership, and liturgy is used in re-interpreting being church. The conclusion brings us to the understanding that true community, as expressed in sharing in communion, is critical in becoming a transformative church. Where people from different walks of life connect in an honest way, the transformation of individuals and communities happens and can still happen.

CONTRIBUTION: This article links to the focus and scope of the HTS journal in the way it connects the practical environment of people who are homeless to the experience of and thinking about church. The article reflects on being church and how to interpret faith in a Corona-defined world. From a theological reflection point of view, the understanding of liturgy and faith are re-imagined in the context of the lives of vulnerable people living in shelters. Key insights of the article poses to help the reader understand how dignity, justice and community help us all to re-imagine how to be church. It challenges the institutional church to become more of the community that embraces and welcomes vulnerable people to experience God and church in their spaces

Keywords: exegesis; ecclesiology; Corona-defined world; shelters; homelessness.

Introduction

I would like to tell you about Johnny Q (not his real name, because we do not know what his real name is due to the fact that he is deaf-mute). He ended up at the shelter for elderly men of the Dutch Reformed Church Oosterlig congregation. The men living in the shelter immediately started taking responsibility for Johnny Q. They cut his hair, cared for his feet (which were very dirty and full of calluses as a result of living on the streets for many years), cut his nails and bathed him every day. The community of elderly, previously homeless men adopted Johnny Q. They cared for him so well that his condition of bowel incontinence was only picked up much later because his comrades kept him so clean and hygienic.

This is one story of the many that came out of a collective response by NGOs, churches, universities and the City Council of Tshwane to the crisis that erupted during lockdown. These stories came about on 23 March 2020, when the president of South Africa announced a 21-day national lockdown (26 March-16 April, extended to 30 April; South African Government News Agency [SAGNA] 2020). It followed from government's declaration of a national state of disaster on 15 March 2020 (Republic of South Africa 2020). That was triggered by the World Health Organization's (WHO 2020) characterisation of COVID-19 as a pandemic (11 March 2020) One of the implications of this decision was that all people who lived on the streets would be moved into permanent or temporary shelters. Together with the City Council, 23 temporary shelters were erected in Tshwane, Gauteng province in South Africa, of which 19 were managed by the different NGOs and churches. Expected and sometimes unexpected caretaking activities unfolded in the months to come: People were helped to get off drugs through a programme in which methadone was administered under the strict supervision of health practitioners. Many people reunited with their families. New skills were learned. New self-worth was discovered through programmes presented by social workers and occupational therapists. Many people had access to medical care, which they had been denied for years as a result of societal discrimination towards homeless people, but also due to a lack of access to opportunities (many people who are homeless are also refugees, who struggle even more than South African citizens to access basic services) (Marcus et al. 2020).

The author is part of an NGO called PEN (Participate Empower Navigate), which focuses on bringing healing to communities of vulnerable men, women and children living in the city or other urban contexts (www.pen.org.za).

At present, the staff at PEN are confronted with the question of the relevance of being church in broken and bleeding communities of the City of Tshwane and other urban areas. During the lockdown, the different NGOs and entities collaborated in new ways in order to collectively care for more than 2000 people who were living in shelters and who had previously lived on the streets (Marcus et al. 2020).

In order to consider the question of the relevance of being church clearly, we have to understand the hermeneutics and embodiment of faith in a Corona-defined world. The author will describe the people who were cared for in the shelters so as to understand the contexts of this discussion. Valuable lessons learned through collaboration are documented. Lessons learned through encounters with people living in the shelters will be highlighted, as will be the effect of the lessons learned on the understanding of being church. The implication of these encounters for the relevance of being church are then considered.

Presenting relevant hermeneutics and a provocative embodiment of faith in a new context

The author's understanding of the hermeneutics and provocative embodiment of faith during the lockdown period was informed mainly by the desperate need for dignity and justice in the way the church responds to vulnerable people. This need should be rediscovered by the church as the way she defines herself as an expression of the Kingdom of God in a post-Corona world.

The question about ecclesiology has always been relevant, and remains very relevant in this time. It is a question that needs to be revisited continuously. Many different models of doing so have been developed through the years. Cardinal Avery Dulles (2002), in his book Models of the church, gives a very comprehensive description of the different models (Mystical Communion, Sacrament, Servant, Herald, Institution and Community of Disciples). For the purpose of this writing, the focus is on the question of relevance in the context of vulnerable people living in shelters. A brief reflection is provided on the institutional church, touching briefly on only some of the elements referred to by Dulles.

Updated descriptions of ecclesiology, or a transformative ecclesiology introduced by German theologian Jürgen Moltmann, were very helpful in reflecting on how to re-interpret church. A more modern-day reflection by the American systematic theologian Patrick Oden (2015:146), reflecting on different books written by Moltmann, says: 'we are to become in the church who we are to be in this world'. Using this description as a baseline, the author will try to describe what is lacking in the understanding of the church through reflecting on own experiences in dealing with the church's response to COVID-19, specifically focusing on her involvement in the support provided to over 20 shelters in Tshwane during the time of lockdown. The author will try to describe how the church can be a true Christian church in any context it finds itself.

The South African practical theologian, Johann-Albrecht Meylahn (2012:1), explains in his book, Church emerging from the cracks, that 'the church is a space in this world where hea-ven and earth reach out to each other. It is a space in the world, but not of the world, as it is touched by heaven'. His understanding is very helpful in thinking about being church. It calls us, as members of the broader church, to be more than and different from the world. It is that space where we as Christians are called to be more than what we can be by ourselves as individuals. It calls us to a different way of being - a way of being that is unfolding from the understanding of how we are church touched by heaven. In other words, it calls each person who sees themselves as part of the church to be kept to a provocative, Spirit-inspired way of loving others and serving justice and dignity. It challenges the broader church, as an institution, to do the same.

In trying to understand the hermeneutics and embodiment of faith in a Corona-defined world, it is important to understand something of the context of the people who form part of these newly founded communities.

A description of the people who filled the newly formed communities in the shelters

The people who filled these newly founded communities in the 19 shelters in Tshwane were people who were living on the streets when President Cyril Ramaphosa announced in a public speech on 23 March 2020 that all people must be removed from the streets at the beginning of lockdown. This forced movement of people went with and caused a variety of different reactions and gave rise to good and bad experiences; inter alia injustices, restored dignity, broken trust, and rebuilt trust.

Different shelters catered for different categories of people. There was a focus on elderly men, younger men who used drugs and younger men who did not use drugs; there also were shelters focusing only on women and others for women with children. A need was identified for shelters for families but, due to a lack of capacity, this need could not be met.

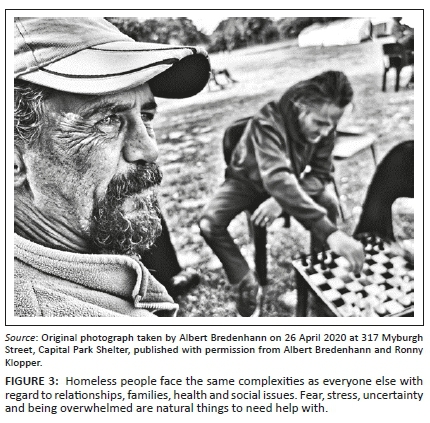

One of the lessons continuously re-learned when working with homeless people is that there is not one definition of homeless people. Homeless people are very different from each other. They become homeless due too many different and complex reasons, and have many different needs and preferences. Many people who are homeless are working somewhere but cannot afford accommodation due to the distance from their home in a rural area. They will then work in the city, sleep on the street and travel home during holidays or over weekends. Others become substance users and need to hustle on the streets to sustain their needs. Alcoholism often goes together with life on the streets. Mental health problems are often a cause or implication of life on the street. Some people who end up on the street are young people who cannot find a job and can no longer stay with their families. Men and women become part of the complicated sex trade and drug industry in trying to survive. These are just a few scenarios of people who end up living on the streets. Homeless people are human beings who deserve and require a dignified and respectful response from the people and communities around them. This was also true of the care that was planned for people who lived in the shelters (Marcus et al. 2020).

There were many intended and/or unintended effects on people who lived in the shelters. Many people were forced to move from their known areas, where they were comfortable and able to look after themselves and their friends (sometimes also family members) in known circumstances. They could hustle for food and livelihoods in communities that had a familiarity and a predictability. Being moved into shelters, these people were forced into new communities with people they did not know. They were taken away from their everyday access to drugs, sex and the many other necessities that meant something to them. Their way of life that they knew before lockdown was disrupted and changed forever. They were put into a totally new context outside of their comfort zones (even though these were sometimes dire and, in the view of other people, undesirable). In the shelters, people had to find a new way of being and a new way of living. Some unintended effects, like in the story of Johnny Q, were new relationships and the establishment of community/communities. Rules and boundaries for living together had to be negotiated and agreed upon. As they were adults with rights to make their own decisions, interesting issues arose; for example, they were not allowed to leave the shelter in order to protect the health of others, but some felt their freedom was being restricted. Bathing and personal hygiene became part of the new rituals to which they had to adhere.

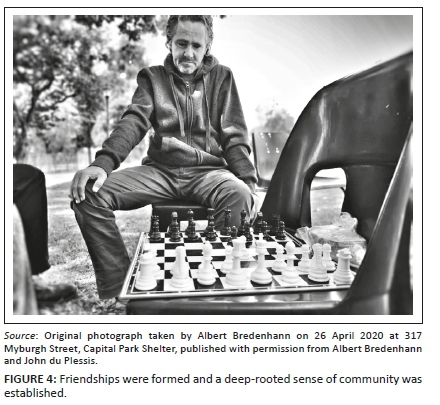

Other unintended effects were that people had access to nutritional food on a regular basis, which had a very positive effect on many of them. Health workers regularly checked every person and made sure they received their medicine correctly and timely. Mental health issues (which are prevalent in homeless communities) were identified and addressed. HIV testing and TB monitoring happened on a continuous basis. Friendships were formed and new partnerships were built. Previously, organisations did not find the need to talk to each other, but now they were forced to talk in order to reach out, work together and come up with innovative solutions. The collaboration combined the strengths of the different partners.

Even formal care institutes and organisations were compelled to collaborate, such as the universities with the City, the City with healthcare institutes, etc. New operational standards had to be developed to manage shelters and to train shelter managers and other supporting staff to do things that had not previously been done. New collaborative entities were put into place during this time, and these are still continuing.

Some church members were moved into action by becoming involved in food provision, and others in developing activities and programmes to support the people living in the shelters. A few individuals understood that merely making friends and building relationships was a very important response in itself. Not many people reached that point of understanding. We found that many people could not cross the barrier they had built for themselves: they could hand out food and clothing, but could not get themselves to engage with the people living in the shelters. Fear and misconceptions about each other keep these barriers in place.

Against the background of describing the context and seeing the people who filled the shelters, lessons were learned about being church.

Lessons learned about being church and finding community

Regarding partnerships

One of the valuable results of the forced collaboration has been the rediscovery of the strength of working together. Across church denominations, across faith groups, but also - and very importantly - across fields of expertise, new ways to collaborate had to be designed. All this collaboration made people realise that we are stronger together.

A few principles crystallised in the experience of taking collaboration forward:

In order to work together well, it became critical to agree on the broad direction of the value that everyone wanted to bring to the beneficiaries: not being outcomes-driven, but rather input-driven. We understood that if we agreed on adding value to the lives of the people, well-defined and thought-through inputs would be most beneficial for the beneficiaries.

There are real risks in working with partners who do not share the same values and principles. If people are in it for selfish and self-enriching purposes, you will never work together well. Regularly coming together to make sure all are in agreement on the direction and on the impact that are needed, continuously revising the strategic direction and re-evaluating the strategy were critical in keeping all on the same page.

Relationships are critical in establishing a foundation of mutual trust and respect. One of the key principles that was rediscovered was that all initiatives, drives or actions were founded in people connecting on a relational level first. Trust is built between people on an individual basis, and this trust is needed to take on the many different and sometimes very challenging problems that might arise in a collective way. Values must be re-visited and re-confirmed throughout each new situation that arises. There was an instance when the police came into the shelters to confirm identities and search beneficiaries in order to find criminal elements. There was a collective response to object to this violation of peoples' rights. The police action was condemned and people's rights were protected: no person, not even in a shelter, can be searched without due process and legal documentation (like a warrant) (see the interpretation of the Constitution as explained by Van Kerwel [2018] below):

Section 14(a) of the Constitution specifically protects the right not to have a person or their home searched. A person's home, it is widely accepted, constitutes the highest expectation of privacy. According to section 36 of the Constitution, rights in the Bill of Rights may be limited by a law of general application, if the limitation is reasonable and justifiable in an open and democratic society based on human dignity, equality and freedom.

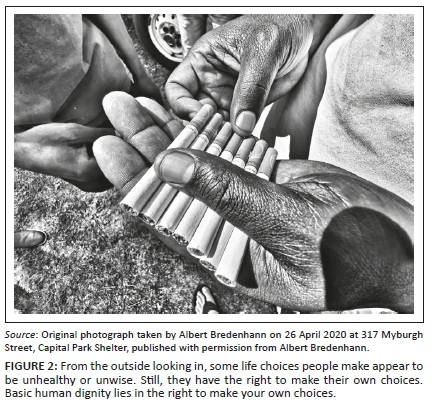

Regarding handouts and dignity

Over the years, PEN (www.pen.org.za) has adopted an established principle of abstaining from giving handouts as a strategy to support vulnerable people. We were taught by our beneficiaries that handouts perpetuate a lifestyle of dependency. We rather want to encourage people to help themselves and develop their own sense of accomplishment. We will come alongside them and help them to restore their faith in their own identity. A big focus rather is put on helping people rediscover their own identity and value. If they look at themselves in a different light and think of themselves as capable and worthy human beings, people gain the confidence to believe in themselves again. Practically, this means serving people's food on a plate and in a cup; providing them with utensils; providing them with proper clean towels and bedding that are worthy of dignity; and allowing them to make their own life choices and mistakes. Dignity is to serve people with love and respect. Not perpetuating dependency is to give people a new focus in life: restoring their faith in their newly defined identity in Christ, that they are worthy and can provide for themselves and their families.

Regarding justice

Justice is not a simple principle to implement and to make part of your approach. South Africa's political context and history have caused extensive complexities in our society. People who are poor in our country are suffering greatly. Their suffering is linked directly to our apartheid history, but also to recent political iniquities caused by corrupt leaders and corrupt systems implemented by a self-serving political leadership that does not prioritise the needs of vulnerable people, but prioritises self-enrichment to the detriment of the vulnerable.

During this period of lockdown, it was confirmed by the media that corrupt officials in Tshwane and Gauteng used the resources meant to care for people living in the shelters to benefit their own families and friends (see reports in City Press [Tau et al. 2020] and News24 [Felix 2020] of city officials handing food parcels to friends and family, etc.).

Agang et al. (2020:345) make a strong argument that Christian leaders are quiet or just not part of many of the political structures because they have come to see economic and political structures as 'not worthy' to engage with, or even too evil. To serve justice to the vulnerable, one of the responses of the church must be to take responsibility to engage with the political and economic systems that enforce injustice.

According to Agang et al. (2020:76), people who live according to Christian values must engage actively in these structures to hold them accountable so as to build a better country for all. Church members and leaders of institutionalised churches will have to take responsibility to become actively involved to influence these corrupted and unjust systems. It will ask of all of us to protect the democratic right of people to be treated with dignity, to have access to health services and education, and to have a fair and trustworthy legal system. All of these will entail engaging in the political sphere to keep leaders accountable. To serve vulnerable communities with justice is to engage with the broken systems that perpetuate poverty, but also to help people to take responsibility for their own lives and choices.

Regarding politics

A real dichotomy is found between the faith world of the church and real life. People are limiting faith to Sunday church service and do not translate the same values into everyday life. This is especially relevant at the local municipality level of government, where local churches should be helped and encouraged to have a clear voice to protect the dignity of vulnerable people in their communities and to address unjust practices (Agang et al. 2020:372).

Regarding language

The church (especially the Dutch Reformed Church [DRC]) is still struggling with the hurt caused by language policies that were used in the past (and in some instances are still being used) to deliberately exclude people from experiencing church community. We, as the DRC, connected community to language and deliberately excluded people in this way. In the South African context, the implication of this exclusion is linked directly to the exclusion of people of specific races. Choices made in the selective use of language can no longer be a reason to exclude people from any experience of community. Building community and sharing the love of God might mean that the church will have to do church in multiple languages. John Calvin already made this point long ago in his commentary on John 19:19-20, in which he argues for translating Jesus' name into three different languages. In this way, people across the whole earth should know about Jesus. According to him, a multilingual church is the only true church (John Calvyn's commentary on John 19, as quoted in StudyLight.org 2020).

Regarding being church

In reflecting on a re-interpreted understanding of the church, it is critical to look at the purpose of the church in a historical way.

Buchanan (2013:170) says: 'The world cannot possibly begin to believe in the reality of an unseen God, extravagant in mercy, lavish in goodness, bent on redeeming and reconciling and restoring creation, until our churches are living object lessons of this very thing.' Based on his view, the church should always be held accountable for the way in which she is true to her calling to be inherently prophetic.

If we think of the call to Reformed churches to stay true to their roots, the expression 'Ecclesia reformata, semper reformanda!' [the church reformed, always reforming] comes to mind (Van Lodenstein 1674). We should continuously ask ourselves: What does it mean for us today to be reforming in a Corona-defined world? It calls on us to continuously revisit our roots and critically re-evaluate where we are in our current context. In an article published online in Presbyterians Today in May 2004, Case-Winters says:

Ecclesia reformata, semper reformanda. This motto calls us to something more radical than we have imagined. It challenges both liberal and conservative impulses and the habits and agendas we have lately fallen into. It brings a prophetic critique to our cultural accommodation - either to the past or to the present - and calls us to communal and institutional repentance. It invites us, as people who worship and serve a living God, to be open to being "re-formed" according to the Word of God and the call of the Spirit.

This quotation calls the author to take the responsibility of having a prophetic voice very seriously. It also calls on her to rethink how we are being church. We should critically review our own identity and relevance in the light of a world redefined by Corona and all its (not yet clear) implications. Moltmann's plea (2015) to help the church to take the 'Crucified God' serious in his context is calling us to do the same in a Corona-defined world.

The ability to keep true to the call of Ecclesia reformata, semper reformanda will influence the ability of the institutionalised church to stay relevant in a changing world, and maybe even to stay true to the original purpose of being a church, which is to have an effect on the broken world through the calling of Jesus to 'love your neighbour as yourself'. A few of the people in the shelters who realised a re-interpreted way to 'love your neighbour as yourself' are captured in the four photographs presented here. The photographs were taken by a well-established photographer, Albert Bredenhann, with the verbal consent of the subjects, during the lockdown period in April 2020 at the shelter run by CAPRRA (Capital Park Residents and Ratepayers Association). These photographs (Figures 1 to 4) form part of a visual diary and cues attesting to the content of what is presented here.

A re-interpreted understanding of being Church in a Corona-defined world

The traditional components that influence the functioning of the institutional church are made up of different elements. Below I name a few that seem relevant in reflecting on re-inventing being church. These comments are very brief and limited only to those relevant to this specific conversation. This is not meant to be a comprehensive discussion on any of the mentioned components of the institutional church. There are many distinguished writers who have done great work on any of these topics. To mention just two, among many: Bonhoeffer's work (1995) on discipleship, and Moltmann (1976) on the concept of being a transformative church.

The few components to be discussed here are prayer, discipleship, leadership, stewardship and liturgy.

Prayer

Prayer is a critical part of the church expressing herself in the intimacy of personal prayer or in the shared experience of communal prayer. The aim is as much to express your inner feelings and words to God, as it is for God to have a space to speak into Christians' lives. In a re-interpreted understanding of church, prayer becomes a protest against the brokenness and the evil found in the world and in systems of political and economic life. The simple and honest way vulnerable people come to express their anger, their pain and their desires reminds of the old creed: Lex orandi, lex credendi, lex vivendi, meaning 'the law of what is prayed [is] what is believed [is] the law of what is lived'. Or, as Plaatjies-Van Huffel (2020:1-2) explains it, 'literally means the law of prayer (the way we worship) is the law of belief (what we believe) or the law of praying (lex orandi) constitutes or establishes the law of believing (lex credendi)'. It emphasises that prayer and belief are integral to each other and are expressed in the way we live our daily lives. The experience of a caring and involved God in prayer builds the belief that God is merciful and just, and this should influence the way people live.

Personal prayer should then become an agenda of transformation, and communal prayer becomes a space of collective outcry against the evil found in each other, and in the systems we design in the political world. If the institutional church then is where heaven and earth reach for each other, it becomes a space for the collective cry towards heaven, addressing the institutional spirit of evil (found in the structures), but also heard by the Spirit of God. That Spirit is not satisfied with a mere passive hearing, but requires of a re-interpreted church to be called to action by declaring prayers that inspire people to live justly as explained by Volf (1996:217). He concurs that 'Doing justice, struggling against injustice, was not an optional extra of Israelite faith; it stood at the very core'. He also goes back to Isaiah 58:6 to emphasise that proper worship (and prayer) is at its core activistic.

Discipleship

Dictionary.com (2020) defines a disciple as:

-

A person who is a pupil or adherent of the doctrines of another.

-

One who embraces and assists in spreading the teaching of another.

-

Any follower of another person.

In other words, to be a disciple is to be a learner and to become a follower. In Christianity, this is taken a little further: it comes down to taking what you have learned and internalising it, then encouraging and inspiring others to do the same (Osmer 2005):

The most important characteristic of a religious practice in the way it teaches its participants to construe their everyday lives in terms of an interpretation of the ultimate context of existence and to align their lives accordingly. (pp. 91-92)

In a re-interpreted church, the place of discipleship becomes one of intense involvement with others. It is all about building deep-felt relationships and trust and becoming a person that others will want to follow, taking personal interest in the well-being and growth of others. This became visible in the lives of people living in the shelters; the way they took responsibility for each other and started to lead themselves, but also their fellow brothers and sisters. It became the quest to 'not leave anyone behind', to become personally, emotionally and economically involved with each other. The process of discipleship is a two-way learning experience. Vulnerable people have a lot to give and to teach. If the church sees her role as facilitating relationships, it should include a constant switch between the roles of being a pupil and of being a teacher. In its successfulness of facilitating the development of people as disciples of Jesus, the church will be asked to affect the lives of people differently. Oden (2015) says that:

Church is transformative when it engages in the development of people to better reflect the life of Christ in their lives, and when this transformation then extends itself beyond the boundaries of a church community, as such people live their lives in new ways wherever they are. (p. 137)

This can become true even in shelters and in affluent church communities.

Mission

This is not an equally popular strategy in all churches. The big missional focus should be to make the world a place where God can be glorified, and not only focusing on the conversion of people. If we think about a re-interpreted church, missional intent should be focused on seeing the world in its wholeness: restoring it to a state of being that is healed, glorifying the Maker. Maybe one should look at it in a systemic way: if one part is broken, it affects all the other parts. If the ecology is suffering under the evil of greed and gluttony, the poor are suffering. If family values are discarded, the daily lives of vulnerable children, women and men are influenced, and this causes even more exposure and vulnerability. The mission should be to make the world a better place for all, according to Agang et al. (2020:372), as it affects all creatures who live in the world. It should include the mission of restoring justice - justice in providing access for all people to resources and opportunities; justice in sharing power and land in a just way; justice in agreeing on what is just in each new context.

Stewardship and leadership

Stewardship is not traditionally seen as a very important part of the heart of the church (Vaters 2018). In a re-interpreted church, good stewardship is part of building credibility. Credibility depends on managing resources in a responsible and transparent manner. Integrity in the way funds, people and donations are dealt with will build trust in the communities in which churches are active. For too long the church has been seen as having very little trustworthiness (Vaters 2018):

The most widespread sin of the modern-day church is poor stewardship. Too many churches are mishandling the money that has been entrusted to us. Many churches are enslaved by unsustainable debt. More churches close their doors every year because they are unable to pay their bills than for any other reason - maybe more than all other reasons combined. (p. 1)

Recent media attention received by churches and their leaders has highlighted that the integrity of the leaders in particular has left nothing to boast about: corruption in the church, as in state entities, is rife, and pastors are misleading the people who put their trust in them (McCauley 2020). Bad theology and irresponsible preaching are tarnishing the reputation of the church. People are led to live lives of dependency and blindly follow irresponsible leaders. Many examples are available to confirm this (e.g. the case of Shepherd Bushiri and his wife and the KwaSizabantu Mission scandal, as recently reported in the general media [BBC.com 2020; DW.com 2020]).All this needs to change in a re-interpreted church. Leadership and stewardship are connected and are a critical part of any movement or organisation. In a re-interpreted church, leaders are those who are not afraid to lead; they are the people who are willing to sacrifice their own comfort for the benefit of the people. We found such leaders in the most unexpected roles in the shelters. They were the servant leaders, people who had proven themselves to understand the plight of those in need and were willing to speak up on their behalf. These leaders looked like the people they represented: they spoke their language and were loved and respected by the people they led because they were part of them. Being a good steward of all that is entrusted to you is a characteristic of a good leader.

Liturgy

In some instances, the author has experienced the rituals expressed in the form of liturgies used in some formal churches as stale and meaningless, e.g. the application of communion as an activity that must be done, rather than a deeply meaningful ritual. In her experience of being church together with vulnerable men and women, communion became alive again: glimpses of this were seen in the sharing of bread and water in the context of sharing a humble meal with a homeless person. The dinner queues became the communion table where the broken and the healed met to share life and stories of hope. People started sharing stories of sacrifices made in order to secure the dignified care provided in the shelters. The rituals, re-interpreted, built a community of people who became part of the body of Christ in new ways: breaking a hard-earned, dry and stale piece of bread on the sidewalk of a busy street in Pretoria became the deepest expression of a sense of belonging to something bigger. Together we drank from the cup of despair and disappointment and found it became sweeter than if it was consumed alone. To sit at this table became a moment of conversion - to follow the Jesus who walks the streets and sits with the lonely and addicted sex worker in Robert Sobukwe Street. New forms of liturgy arose in the washing of the feet of Johnny Q and the playing of chess with John du Plessis. Sharing in community led to visualising the body of Christ.

Conclusion

In the end, the most comprehensive answer the author could find to the question of how to re-interpret the relevance of being church in a post-Corona world was found in listening to the experiences of the many vulnerable people affected by Corona. In an effort to understand the hermeneutics and embodiment of faith in a Corona-defined world, a better understanding of who the vulnerable people were who filled the shelters, and listening to their stories about God, about their own faith, along with the lessons learned from their stories of becoming church in a re-interpreted way, helped the author to understand that dignity, justice and community form the baseline in re-interpreting being church in a Corona-defined world. Collaboration, and acting from a shared base of value-driven responses, helped the author to draft models for dignified and just care. The conclusion was formulated that true community, and sharing true communion in an honest, just and dignified way, brought us to a re-interpreted experience of being church. Our understanding of who God is and who we are, have developed and deepened. This expression of community will help the institutional church '… to become in the church who we are to be in this world' (Oden 2015:146).

Acknowledgements

Albert Bredenhann is the photographer who took the photos with the verbal permission of the participants.

John du Plessis and Ronny Klopper who were willing to share their experiences and photos of themselves.

CAPRRA and its members for taking on the great journey of opening and managing a shelter.

Prof. D.P. Veldsman for his guidance and support in bringing experiences to words.

Thank you to all the people who taught me so much through their bravery and enduring hardship everyday living on the streets of our towns and cities.

Competing interests

The author declares that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Author's contributions

M.v.N. is the sole author of this research article.

Ethical considerations

Verbal permission was obtained from interviewees to be identified in published answers and images.

Funding information

This research received no specific funding from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in the article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of any affiliated agency of the author.

References

Agang, S.B., Forster, D.A. & Hendriks, H.J., 2020, African public theology, Langham Creative Projects, Carlisle. [ Links ]

Bonhoeffer, D., 1995, The cost of discipleship, Touchstone, New York, NY. [ Links ]

British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), 2020, 'Shepherd Bushiri: Preacher flees South Africa ahead of fraud trial' viewed 17 December 2020, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-54949819. [ Links ]

Buchanan, M., 2013, Your church is too safe, Zondervan, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Case-Winters, A., 2020, 'Our misused motto', Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), viewed 17 December 2020, from https://www.presbyterianmission.org/what-we-believe/ecclesia-reformata/. [ Links ]

Dictionary.com, 2020, 'Discipleship', viewed 16 December 2020 from https://www.dictionary.com/browse/discipleship?s=t. [ Links ]

Dulles, A., 2002, Models of the church, Doubleday, New York. [ Links ]

DW.com, 2020, 'Kwasizabantu scandal rocks South Africa', viewed 17 December 2020, from https://www.dw.com/en/kwasizabantu-mission-scandal-rocks-south-africa/a-55162733. [ Links ]

Felix, J., 2020, 'Covid-19 corruption: SIU swoops on Tshwane metro, Gauteng education dept for alleged PPE graft', News24, 27 October, viewed 18 December 2020, from https://www.news24.com/news24/southafrica/news/covid-19-corruption-siu-swoops-on-tshwane-metro-gauteng-education-dept-for-alleged-ppe-graft-20201027. [ Links ]

Marcus, T.S., Heese, J., Scheibe, A., Shelly, S., Lalla, S.X. & Hugo, J.F., 2020, 'Harm reduction in an emergency response to homelessness during South Africa's COVID-19 lockdown', Harm Reduction Journal 17, Art. 60, viewed 23 April 2021, from https://harmreductionjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12954-020-00404-0. [ Links ]

McCauley, R., 2020, 'Church and leaders must stand up and call out false prophets among us', Times Live, 22 November, viewed 18 December 2020, from https://www.timeslive.co.za/sunday-times/opinion-and-analysis/2020-11-22-church-and-leaders-must-stand-up-and-call-out-false-prophets-among-us/. [ Links ]

Meylahn, J.A., 2012, Church emerging from the cracks, African Sun Media, Bloemfontein. [ Links ]

Moltmann, J., 1976, Human identity in Christian faith, Raymond Fred West Lectures, Stanford Junior University, Stanford CA. [ Links ]

Moltmann, J., 2015, The Crucified God, 40th anniversary edn., Augsburg Fortress Publishers, Minneapolis MN. [ Links ]

Oden, P., 2015, The transformative church: New ecclesial models and the theology of Jurgen Moltmann, Fortress Press, Minneapolis. [ Links ]

Osmer, R.R., 2005, The teaching ministry of congregations, Westminster John-Knox Press, Louisville, KY. [ Links ]

Plaatjies-Van Huffel, M.-A., 2020, 'Rethinking the reciprocity between lex credendi, lex orandi and lex vivendi: As we believe, so we worship. As we believe, so we live', HTS Theological Studies, 76(1), a5878. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v76i1.5878 [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa, 2020, 'Declaration of a National State of Disaster - Disaster Management Act (57/2002) by the Minster Minister of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs', Government Gazette No. 313, 15 March, viewed 23 April 2020, from https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202003/43096gon312.pdf. [ Links ]

South African Government News Agency (SAGNA), 2020, 'President Ramaphosa announces a nationwide lockdown', viewed 24 April 2020, from https://www.sanews.gov.za/south-africa/president-ramaphosa-announces-nationwide-lockdown. [ Links ]

StudyLight.org, 2020, 'Bible commentaries: Calvin's commentary on the Bible: John 19', viewed 12 December 2020, from https://www.studylight.org/commentaries/cal/john-19.html. [ Links ]

Tau, P., sama Yende, S., Stone, S., Khumalo, J., Ngcukana, L., Masuabi, Q. & Erasmus, D., 2020, 'Councillors accused of looting food parcels meant for the poor', City Press, 19 April, viewed 16 December 2020, from https://www.news24.com/citypress/News/councillors-accused-of-looting-food-parcels-meant-for-the-poor-20200419. [ Links ]

Vally, R. & De Beer, S., 2017, 'Pathways out of homelessness', Development Southern Africa 34(4), 383-384, viewed 24 April 2021 from https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2017.1335098. [ Links ]

Van Kerwel, W., 2018 'Can the police search a person without a warrant of arrest?', viewed 12 April 2021, from https://www.mblh.co.za/NewsResources/NewsArticle.aspx?ArticleID=2334. [ Links ]

Van Lodenstein, J., 1674, Beschouwinge van Sion ofte aandagten en opmerckingen over den tegenwoordigen toestand van't gereformeerde christen volk: Gestelt in eenige t'samenspraken, Van Hardenberg, Amsterdam. [ Links ]

Vaters, K., 2018, 'The invisible scandal: How bad debt and poor stewardship are killing the Church's reputation', viewed 13 April 2021, from https://www.christianitytoday.com/karl-vaters/2018/august/invisible-scandal-bad-debt-poor-stewardship-kiliing-church.html. [ Links ]

Volf, M., 1996, Exclusion and embrace, Abingdon Press, Nashville, TN. [ Links ]

World Health Organization, 2020, 'WHO timeline - COVID-19, 8 April statement', viewed 23 April 2020, from https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/08-04-2020-who-timeline---covid-19. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Marinda van Niekerk

marinda@pen.org.za

Received: 18 Jan. 2021

Accepted: 20 Apr. 2021

Published: 25 June 2021

Note: Special Collection: From timely exegesis to contemporary ecclesiology: Relevant hermeneutics and provocative embodiment of faith in a Corona-defined world - Festschrift for Stephan Joubert, sub-edited by Willem Oliver (University of South Africa).