Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

HTS Theological Studies

On-line version ISSN 2072-8050

Print version ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.77 n.4 Pretoria 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v77i4.6292

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

A socio-historical study of the adoption imagery in Galatians

Chih Wei Chang

Taiwan Graduate School of Theology, Taipei, Taiwan

ABSTRACT

This study investigated how Paul's Jewish background, including some elements of pre-rabbinical Jewish literature, influenced the letter to the Galatians with regard to the concept of adoption (υἱοθεσία) (Gl 4:1-7). As Paul was writing to a Gentile audience, wanting to persuade them to return to the true gospel, metaphors of adoption, embedded in the understanding of the Graeco-Roman household, became effective communication bridges to reach his audience. Within this framework, Israel's God was depicted as the caring father of the household, who through his son Jesus Christ redeems all human beings from the status of slaves to that of children with full rights of inheritance.

CONTRIBUTION: God's redemption is not merely a forensic sense of justification but also the imagery of relationship in the household by which God does not merely set one free from sin by securing us through Jesus Christ into the society of the righteous, but also adopts us into his family

Keywords: socio-historical study; adoption; metaphor; Galatians; freedom.

Introduction1

The word υἱοθεσία (adoption) is very significant in terms of God's salvation of humanity, but Bible scholars have neglected and misinterpreted it for a long time (Burke 2006:25). During the 16th and 17th centuries, Reformed theologians regarded adoption as part of justification (Ferguson 1986:83). The post-Reformation theologian John Leith, for instance, understood 'adoption as a synonym for justification' (Leith 1973:99). Traditional commentators have also interpreted Paul's letter to the Galatians using 'justification by faith' as the primary lens and principle (Rhoads 2004:248).

Burke (2006:26) claims that adoption ought not to be subsumed under justification nor mistaken as a synonym of justification. On the contrary, adoption is the essence of Pauline theology, the greatest privilege that the gospel offers, and can be considered a higher climax following the grace of justification. Peppard (2011:96) also indicates that the imagery is of a household, where the transition from slave to son is brought about by the 'redemption' of the slave's price and subsequent 'adoption'. In other words, God does not merely provide justification for the people and then leaves them with nowhere to go: he adopts them into the warmth and security of his household (Burke 2006:25), as is pointed out in the passages which say that God does not merely set us free from sin by rescuing us through Jesus Christ into the society of the righteous; he also adopts us into his family so that we can call him 'abba Father' (Gl 4:6; Rm 8:15). Moreover, it cannot be overlooked that the metaphor of adoption was not unknown within the Graeco-Roman social context. On the other hand, it is difficult to know what Paul had in mind when he used the metaphor to explain the salvation of God, as there were different backgrounds - Old Testament, Greek and Roman - and his multicultural audience to consider.

Problem statement

Different perspectives of Graeco-Roman culture and Old Testament or Jewish traditions have been emphasised to explain the term 'adoption'. Some scholars claim that when Paul used the term adoption, he was concerned with the Old Testament or Jewish tradition of a 'Second Exodus' expected by Israel (Byron 2003; Holland 2004; Scott 1992); others relate the term to the socio-historical institution of Graeco-Roman culture (Bartchy 1992; Goodrich 2013; Tsang 2005).

I would like to establish in this article whether it could be assumed that there is a dichotomy between Jewish and Gentile symbol systems. Moreover, if one presupposes that Paul wrote not to Jews but to non-Jewish audiences, could those audiences have understood what Paul explained if the metaphors of adoption for God's soteriology came from a Jewish background? although many scholars have shown that Paul's adoption metaphors are preceded by a rich history of similar images in Jewish literature and are connected to Old Testament scriptures that echo in Pauline passages (Eph 1:3-14; Gl 3-4; Rm 8), can they really be separated from the Graeco-Roman physical adoption?

This study will, firstly, look at the adoption imagery in the Old Testament, the Second Temple literature and the 1st century AD Graeco-Roman world, and then, secondly, the exegesis of Galatians 4:1-7, taking into consideration the socio-historical context of the adoption imagery.

Method of research

This study is based on the carefully constructed theory of metaphor Lakoff and Johnson (2003) and Soskice (1985). Human languages are very much a matter of metaphor (Lakoff & Johnson 2003:3). Metaphors not only have the potential to change minds, to correct perceptions and to alter behaviour but also have the power to affect changes in people's lives. Thus, the authors of the Bible have included numerous metaphors in their writings through which they tried to persuade, move and motivate. Metaphors do not only relate to an unusual and ornamental use of words, as Aristotle said (Poetics. 1458a), but also to the fundamental conceptualisation of certain realities in terms of other experiential realities (Lakoff & Johnson 2003:5, 117; Soskice 1985:15). Therefore, there are numerous ordinary terms that are metaphorical.

There are at least two mental effects on the listener who can be learned from Aristotle's theoretical considerations on metaphors. Firstly, metaphors can be knowledgeable and contribute to learning by having a rational effect (Aristotle 1926:3:10. 1-4). Aristotle describes metaphors and comparable expressions that evoke wit and esteem, but which require some mental effort (Van der Watt 2000:10). However, a metaphor is lively when it evokes a new meaning that surprises the hearer. In doing so, it passes on knowledge to the listener. Secondly, according to Aristotle, metaphors can affect the listener's disposition; they are used not only to enhance the style of the oration but also to give pleasure to the listener (Aristotle 1926:3.2.8). Therefore, the aesthetic value of metaphors was significant in classical rhetoric.

Apart from the above-mentioned effects, metaphors also have the power to affect a behavioural response, having great potential to orientate and re-orientate readers or listeners through the imagery given from the author's perspective (Lakoff & Johnson 2003:3; Van Rensburg 2005:412).

In summary, the aim of a metaphor is threefold:

-

Firstly, it verbalises something that cannot be described adequately in everyday experiential terms (Van Rensburg 2005:412).

-

Secondly, it provides a new picture according to how the hearer or reader sees the point in question. By understanding an image, it shapes and influences perceptions, emotions and identity formation of individuals and groups (Heim 2017:25).

-

Thirdly, it gives tension that provokes the hearer or reader into some reaction within his or her culture, experience, knowledge and properties (Van Rensburg 2005:412).

By taking these three elements into account, the adoption imagery in Galatians has to be based on semantic conventions within the specific book. This implies that the reader should be able to relate the symbols in the text of Galatians to the referent (Van Rensburg 2000:2). As such, a metaphor is regarded as a common ground of understanding between author and recipients. For this reason, it is necessary to study the text closely, both syntactically and semantically, to recognise a particular word, phrase or image as metaphor. In addition, as it was set in cultural and social conditions different from today, the adoption imagery is also comprehended by considering the socio-historic context (Van Rensburg 2000:13). Therefore, one can understand the power of the concepts in a text when their meaning for the period in which the text was written has been determined.

The definition of the concept υἱοθεσία [adoption] in Galatians

The concept 'adoption' in Galatians is defined in this study as

The process through which a person declares formally and legally that someone who is not their own child is henceforth to be treated and cared for as a legitimate child, including complete rights of inheritance (υἱοθεσία - Louw and Nida, domain 35.53); the opposite of adoption is the process through which a biological child is forsaken, depriving this person of the rights of inheritance (ἔρημος - Louw and Nida, domain 35.55).

This definition is used to filter out the words and phrases connected with the concept υἱοθεσία in the relevant literature.

Adoption imagery in the Old Testament

Although the term υἱοθεσία is not used in the Septuagint or in any other Jewish source of the period (Scott 1992:61), the concept of adoption is referred to by other terms and formulae that can be evaluated. This concept occurs in at least three passages in the Old Testament: Genesis 48:1-7, Exodus 2:1-10 and Esther 2:5-7, 15. These portions, as substantial cases of adoption (Braaten 2000:21; Scott 1992:74), are now investigated.

Adoption in Genesis 48:1-7

When Jacob was ill (Gn 48:1) and reminisced about the promise made to him by God (Gn 48:3-4), he met with his grandsons, Manasseh and Ephraim, elevating them to his own (adoptive) sons, making them leaders of the 12 tribes (Gn 48:5; cf. Waltke 2001:596). With this passage, it can be argued that Jacob formally adopted his grandsons (Matthews 2005:863; Wenham 1994:463), putting them on par with his two eldest sons, Reuben and Simeon (Gn 29:32-22). The promise which Jacob had received from God (Gn 48:3-4) empowered him to adopt the sons of Joseph as his sons. God had promised Jacob the increase of his seed into a multitude of peoples and Canaan as an eternal possession to his descendants, who now included the two sons of Joseph born in Egypt. Technically, Joseph's sons could not be legitimate sons and tribal ancestors because they were born in Egypt of an Egyptian mother (Waltke 2001:596; Westermann 1987:314). Only Jacob could make this happen. Because of Jacob's proclamation, therefore, those outside his house received - by adoption - a share of the promised inheritance equal to that of his own eldest sons. This type of adoption within a family was considered customary in the ancient Orient as it is recorded in a text from Ugarit in which a grandfather adopts his grandson as his heir (Wenham 1994:463).

Signs of adoption can be understood from the following: '… Joseph brought them near him; and he (Jacob) kissed them and embraced them' (Gn 48:10). The phrase 'kissed and embraced them' could be an indication of adoption (Wenham 1994:464). Later in the passage, Jacob says that 'his younger brother shall be greater than he …' (Gn 48:19) and 'puts Ephraim ahead of Manasseh' (Gn 48:20), making them the ancestors of tribes tracing back to his own sons, such as Judah and Benjamin.

The following could indicate another allusion to adoption in Genesis: 'Joseph removed them (Manasseh and Ephraim) from his father's knees' (Gn 48:12). The phrase 'from his father's knees' does not imply that the boys were actually sitting on Jacob's knees. More reasonably, they had stood by his knees (Wenham 1994:464). The act of placing them upon his knees could symbolise a legitimation of them as equals of his sons, a demonstration of intra-family adoption (Waltke 2001:596). Therefore, by proclaiming Manasseh and Ephraim as his, kissing, embracing and moving them onto his knees, Jacob adopted them as his sons.

Exodus 2:1-10

Because of the persecution under Pharaoh, Moses' mother (Jochebed) kept him alive by putting him in a papyrus basket left among the reeds of the river (Ex 2:2-3). Moses' sister, Miriam, watched to see what would happen to him (Ex 2:4). She suggested to the daughter of Pharaoh to arrange a wet nurse for the child, which she accepted (Ex 2:7-8). The act of adoption becomes clear when Pharaoh's daughter '… took him as her son. She named him Moses, because, she said, "I drew him out of the water"' (Ex 2:10). Moses is legitimately adopted by the Princess as her son (Stuart 2006:92-93).

Adoption in Esther 2:5-7

Esther 2:7 describes the relationship between Mordecai and Esther:

Mordecai had brought up Hadassah, that is Esther, his cousin, for she had neither father nor mother; the girl was fair and beautiful, and when her father and her mother died, Mordecai adopted (לקָחָ֧הּ) her as his own daughter. (Es 2:7)

The passage clearly portrays the event of adoption (Braaten 2000:21-22).

Conclusion

Some clear elements define the phenomenon of adoption in the Old Testament. Firstly, in the case of Jacob's grandsons' adoption, Jacob was on his deathbed when he decided to adopt as his own the two sons of Joseph, Ephraim and Manasseh, and to pass on to them the inheritance. This adoption was regarded as an intra-family adoption. Secondly, Moses' adoption was an informal adoption, not a legal one. Moses was brought up by Pharaoh's daughter, but he did not become an heir of Pharaoh. Finally, according to the account of the adoption of Esther, Mordecai had raised his orphaned niece as his daughter. She did not continue the household of Mordecai. Therefore, the Old Testament adoption cannot meet the definition of the concept 'adoption' in Galatians, as defined above (cf. 4).

Sonship (adoption) imagery in the Old Testament and Second Temple literature

As has been argued, there is nothing in the Old Testament about the Israelites being adopted into God's family, nor is the institution of adoption of a single person into a family portrayed. Although one may think that the imagery of adoption as sons of God emerges in the Old Testament, it refers more to sonship than adoption, as becomes clear from the fact that the term and concept of adoption are absent in the Old Testament and in the early Jewish literature (Burke 2006:50).

However, the sonship metaphor can be construed as a vehicle for Roman adoption. Consequently, it is, from my perspective, necessary to take the sonship metaphor into consideration when studying the adoption metaphor, although they are different concepts. Paul assumed that his audience was at least familiar with a Jewish frame of reference (Gl 3:6-9, 16-18; 4:21-31). Therefore, understanding the metaphor of Jewish sonship may explain why Paul chose not to use the sonship metaphor, but used instead the adoption (υἱοθεσία) metaphor in Galatians. This may help to avoid falling into the traditional dichotomy between sonship and adoption metaphors in either Jewish or Graeco-Roman scholarly backgrounds.

The nation of Israel as son of God

The imagery of the LORD identifying the nation of Israel as his son is evident in Exodus 4:22-23: 'Then you shall say to Pharaoh, "Thus says the LORD: Israel is my firstborn son (בְּנִ֥י בְכֹרִ֖י)". I said to you, "Let my son go that he may worship me …"'. The metaphor of the firstborn implies that Israel belongs exclusively to the LORD. It emphasises the special filial connection between the LORD and Israel by which Israel enjoys God's care and protection from the threats of Pharaoh (Heim 2017:274). The purpose of calling Israel God's son is that he worships him. The LORD, as a father, elected Israel for no other reason than that he loved the son who was suffering, that is, Israel (Ex 3:7-8).

The metaphor of the father-son relationship is also used in Deuteronomy 8:5: 'Know then in your heart that as a parent disciplines a child so the LORD your God disciplines you'. In this passage, after recounting Israel's 40 years' wandering in the wilderness (Dt 8:2), the LORD, as a father, disciplines his son, within the framework of the covenant, because of his moral behaviour. The father-son metaphor conveys the filial, intimate and responsible relationship between Israel as a son and the LORD as a father (Heim 2017:274).

Israel, like a disobedient son, goes against the LORD his father, as described in the song of Moses:

[Yet] his degenerate children ([בּנָ֣יו] - singular) have dealt falsely with him, a perverse and crooked generation. Do you thus repay the LORD, o foolish and senseless people? Is not he your father, who created you, who made you and established you?. (Dt 32:5-6)

Israel, as son of the LORD, rebels against his father. Having been faithless to the LORD, the LORD punishes the Israelites by hiding from them (Dt 32:20), making them jealous with 'what is no people' and provoking them with 'a foolish nation' (Dt 32:21).

Similarly, Isaiah also uses the metaphor of the father-son relationship in the plural to describe the LORD's faithfulness and Israel's disobedience:

Oh, rebellious children (sons [בָּנִ֖ים]), says the LORD, who carry out a plan, but not mine; who make an alliance, but against my will, adding sin to sin … For they are a rebellious people, faithless children (sons [בָּנִ֖ים]) who will not hear the instruction of the LORD. (Is 30:1, 9)

Another example from Isaiah:

[…B]ring my sons (בנַי֙) from far away and my daughters from the end of the earth - everyone who is called by my name, whom I created for my glory, whom I formed and made. (Is 43:6-7)

This passage speaks of Israel being gathered from the diaspora as sons and daughters of the LORD who created them and gave them safety and their enemies as ransom (Is 43:2-4). Although Israel has been unfaithful to the commandments of their father, the LORD is still faithful to his people and loves and acts graciously towards his son, as Isaiah says:

I will recount the gracious deeds of the LORD, the praiseworthy acts of the LORD, because of all that the LORD has done for us … that he has shown them according to his mercy, according to the abundance of his steadfast love. For he said, 'Surely they are my people, children (sons [בָּנִ֖ים]) who will not deal falsely'; and he became their saviour. (Is 63:7-8)

Likewise, Jeremiah anticipates the restoration of Israel as a whole after the exile; he proclaims the actions of the LORD towards his son: 'I will lead them back … for I have become a father to Israel, and Ephraim is my firstborn' (Jr 31:9). God's love for his son is also related in the book of Hosea 11:1: 'When Israel was a child, I loved him, and out of Egypt I called my son (לִבְנִֽי)'. Although Israel is a stubborn, rebellious son, disobedient to his father, God, the faithful father, restores his beloved son according to his mercy and steadfast love.

According to these passages, the sonship metaphors clearly carry a strong component of nationalism and exclusivity.

The nation of Israel as son of God in the Early Jewish literature

Early in the Jewish era, the metaphor of sonship was highly emphasised because of an aggressively Hellenised Jewish culture that caused social conflict and cultural hostility between Jews and non-Jews.

The sonship metaphor emphasised Israel's nationalism as distinguished from other nations, as illustrated in the Book of Wisdom 12:19-21:

Through such works you have taught your people that the righteous must be kind, and you have filled your children [sons] (τοὺς υἱούς σου) with good hope, because you give repentance for sins. For if you punished with such great care and indulgence the enemies of your servants (παίδων σου) and those deserving of death, granting them time and opportunity to give up their wickedness, with what strictness you have judged your children [sons] (υἱούς σου), to whose ancestors you gave oaths and covenants full of good promises …

The context of this passage shows the ethnic division between the Israelites (τοὺς υἱούς σου) and the Egyptians as their enemies (ἐχθροὺς) (Heim 2017:286). As in the Old Testament (Dt 8:5), God as a father disciplines his son Israel and brings redemption to him but tribulation to other nations (Egypt and Greece). God rescues his son by giving him the law, which is the imperishable light, leaving the other nations to live in darkness (Wis 18:1-4). Thus, the law is the main factor that distinguishes the son of God from other nations. The author tries to reinforce the boundary of the Jewish audiences in the Hellenistic milieu in order to strengthen their national identity as children of God.

Another sonship metaphor is used in 3 Maccabees by Philopater who says:

27bSend them back to their homes in peace, begging pardon for your former actions! 28 Release the children ([sons] υἱοὺς) of the almighty and living God of heaven, who from the time of our ancestors until now has granted an unimpeded and notable stability to our government. (3 Macc 6:28)

In this passage, the author employs the sonship metaphor by using the words of the Gentile king to underscore the particularity of the Jewish people as the children of God (cf. 3 Macc 2:2-20; 6:2-15; 7:6-7) (Heim 2017:286). There was no concern to make proselytes of the Gentiles, because God was the father of Israel only, he cared for his sons and made an alliance with them (3 Macc 7:6-7).

Echoing the concept of the particularity of the Jewish national identity is the sonship metaphor in Sirach 36:16-17:

Gather all the tribes of Jacob, and give them their inheritance, as at the beginning. Have mercy, o Lord, on the people called by your name, on Israel, whom you have named your firstborn.

The context of Sirach 36 is a judgement on the enemies of Israel against the backdrop of the election of Israel as son of God, who is 'called' and 'named'. The passage points out that Israel's God will maintain his covenant with him and Israel will lead all nations to recognise the father (Sir 36:22). At last, Israel will destroy the nations to show the glory of his father (Sir 36:3-4). The contrast between the concept of the redemption of Israel and the judgement of other nations can also be seen in Judith 9:12-14 and in Psalm of Solomon 17:26-29; 18:4-5 (cf. Heim 2017:291).

According to these passages from the early Jewish era, the metaphor of Israel as son of God had the same meaning as in the Old Testament. Because of the reality of Hellenisation that endangered their identity, the authors tried to uphold their identity by using the metaphor of sonship: the unique and exclusive privilege and position of Israel as the chosen son of God distinguished them from the other nations.

Conclusion

The metaphorical depiction of the nation of Israel as the son of God in the Old Testament and Early Jewish Literature evokes significant imageries. Firstly, Israel's God, as a father, selects the nation of Israel as his son. Secondly, in the early Jewish era, the image of the father-son relationship became stronger, distinguishing the nation of Israel from other nations.

Adoption imagery in 1st century AD Graeco-Roman world

The study turns now to the discussion of adoption in the Graeco-Roman social context. In order to construct the social meaning of adoption, the Roman law is investigated together with the writings of philosophers and poets.

Roman law

Firstly, Roman adoption was to ensure the inheritance and the transmission of power from the adoptive father to the adoptee. The primary purpose was for the paterfamilias to be able to pass on his potestas to a suitable heir after his death. One had to possess the potestas with legal independence (sui juris), as mentioned in the Digest of Justinian 28:

In adoptions, inquiry is made as to their wishes only of those who are sui juris. But if people are being given by their father into adoption, in relation to them the choice of both parties must be considered through their consenting or their failing to make objection. (Krueger & Watson 1985:19-20)

From this perspective, an adopted son would really become the son and agent of the adoptive father; he was neither a substitute son nor some kind of second-class son, but exchanged his own status for the status of the adoptive father (Peppard 2011:54). His former father's name, status and family cult were gone; everything had been brought under the power of his new father.

Secondly, there were some rights and duties in Roman adoption, as Cicero (1891) says:

[… W]hen extremely old, adopted as sons, the one Orestes, and the other Piso. And these adoptions, like others, more than I can count, were followed by the inheritance of the name (nomen) and property (pecunia) and sacred rites of the family (sacrum). (p. 35)

This statement shows that the Roman concept of adoption was rooted in the religious basis of the household, as each family had its own cult or sacred things (Burke 2006:66). Duty of a person who was adopted was not only to carry on the name of the adopter but also to inherit the property and, most important, to protect the cult of a family from dying out (Peppard 2011:51; Scott 1992:9). The ancient Roman household was filled with gods and each god was venerated in accordance with ancestral custom. Gods provided for the family, guarding the storehouse, guaranteeing the supply of food and protecting the entire household (Burke 2006:66). The genius [the divine spirit] or numen [divine power] of the family was the focus of domestic worship and referred to as its protective force and the living spirit of the paterfamilias. Thus, the adoptee was responsible for securing his adoptive father's rights and perpetuate succession. Otherwise, the adopted son could lose his legacy under Roman law (Lindsay 2009:107).

Thirdly, an adoptee had to be young, as written in the Digest of Justinian 1.7.40:

A younger person cannot adopt an older; for adoption imitates nature; and it seems unnatural that a son should be older than his father. Anyone, therefore, who wishes either to adopt or arrogate a son should be the elder by the term of complete puberty, that is, by eighteen years. (Krueger & Watson 1985:22)

All in all, in Roman law, the power of the father (paterfamilias potestas) to adopt was supreme. Adoption was a means to secure a future for his inheritable estate, to carry on his name and to officiate his household cult. An adopted son, who could supersede a natural son in favour, had the responsibility to increase the inheritance of his adoptive father.

Social advancement through adoption

Because freedmen could receive citizenship (Lindsay 2009:123), Roman law also provided the opportunity for a former slave to be adopted by a paterfamilias to perpetuate his line. As adoption included an artificial mode of acquiring status within the Roman family, adoption had clear relevance to freedmen because of the possibility of rapid social advancement if they were adopted by Roman citizens (Lindsay 2009:131). This is encapsulated by Justinian: 'A person's rank is not lowered by adoption, but it is raised' (Justinian Digest 1.7.35; Krueger & Watson 1985:22).

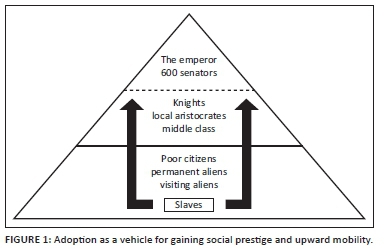

Although Roman law prohibited freedmen from marrying into the senatorial class, they could, through adoption, gain social status and rise from the bottom of society (slave) to the middle class and become aristocrats or knights (See Figure 1).

Adoption as a vehicle for gaining social prestige and upward mobility can also be observed in the writings of Seneca the Elder (1974:1.6.6) who, writing on how one should examine a woman before deciding to marry her, compares the situation with a youth being requested for adoption:

If [a young man] wants to go, he should inquire how many ancestors the old man who seeks him has, what rank they are, what the old man's wealth is - whether he can auction himself off at a sufficient price. (Seneca 1974:1.6.6).

Seneca (1974:2.4.13) also mentions upward mobility; one example: 'Now through adoption, this [child] from the very bottom is grafted on to the nobility'.

Metaphorical use of adoption: The Roman emperor as paterfamilias

In 2 BC, on 05 February, Caesar Augustus was given the title of pater patriae (father of the fatherland):

In my thirteenth consulship the Senate, the equestrian order, and the whole people of Rome gave me the title of pater patriae, and resolved that this should be inscribed in the porch of my house and in the Curia Julia and in the Forum Augustum …. (Peppard 2011:61)

After his death, the fatherly image of the divine Augustus was conferred on the legend of a new coin issue: 'Divus Augustus Pater' (Peppard 2011:61). In Roman world view, especially during the 1st century, the father-son relationship was not primarily a generational or begotten relationship, but relied on the father's power and determination-as was the case in the relationship between the Roman Emperor and the Roman citizens.

Strabo (63 BC - 24 AD) regarded Augustus' fatherly status as a metaphor for good authority:

But it was a difficult thing to administer so great a dominion otherwise than by turning it over to one man, as to a father; at all events, never have the Romans and their allies thrived in such peace and plenty as that which was afforded them by Augustus Caesar, from the time he assumed the absolute authority… (Strabo 1924:6.4.2)

Seneca the Younger (4 BC - 65 AD) muses about the fatherly title:

This [clementia (clemency)] is the duty of a parens, and it is also the duty of a princep, whom not in empty flattery we have been led to call 'pater patriae'. For other designations have been granted merely by way of honour; some we have styled 'the great' and 'the fortunate' and 'the august', and we have heaped upon pretentious greatness all possible titles as a tribute to such men. But to the pater patriae we have given the name in order that he may know that he has been entrusted with patria potestas, which is most forbearing in its care for the interests of his children and subordinates his own to their interests. (Seneca 2009:1.14.2)

The metaphoric use of the adoptive father is clear: the stability and peace Augustus' power brought to the world was built upon the emperor's role as the father of the Empire similar to that of the paterfamilias of a large family (Harrison 2011:80). The emperor was not only the father of Rome, as Romulus was but was also the father of everyone in the Province of Asia (Peppard 2011:66).

Conclusion

What has been discussed above is a general depiction of adoption in Roman law and literature and provides an understanding of adoption. In Roman law, the power of the father (paterfamilias potestas) to adopt was supreme. Adoption was a means to secure a future for his inheritable estate, to carry on his name and to officiate his household cult. An adopted son, who could supersede a natural son in favour, had the responsibility to increase the inheritance of his adoptive father. Furthermore, he could also be promoted from the bottom strata of society and installed among the nobility. According to several examples of social advancements made through adoption and the metaphorical use of adoption, adoption might have been a way to advance one's status through the father's power, which was based on the authority of the Emperor, who brings stability and peace to the people and adopts a son to whom he transfers his power:

Metaphors are based on semantic conventions within a given book and/or a certain social historical context. The metaphor of adoption has been discussed diachronically - its occurrence in the Old Testament - and synchronically - in the 1st century Jewish culture and in the 1st century Graeco-Roman world. The focus now shifts to Paul's letter to the Galatians. (Van der Watt 2000:7-10)

Adoption in Galatians 4:1-7

I utilise the method of exegesis used by Van Rensburg and others (Van Rensburg 2015:37-221).

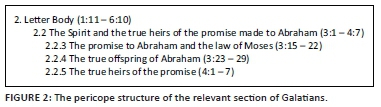

Place of Galatians 4:1-7 in Galatians

The pericope structure of the relevant section of Galatians can be represented in the following way (see Figure 2): 2

After arguing the limited and temporary duration of the function of the Law (Gl 3:15-22) and asserting the priority of the Abrahamic covenant and the subsidiary nature of the Law (Gl 3:23-29), in Galatians 4:1-7, Paul restates the content of Galatians 3:15-29 from another angle: The Spirit attests that believers are no longer slaves, but sons and therefore heirs.

The genre of Galatians 4:1-7

The pericope forms part of the letter body in the probatio (argument) (Gl 3:1-6:10) (Betz 1979:198199) to prove that the gospel which Paul has proclaimed is true: The Galatians must know that they are no longer slaves, but sons and therefore heirs.

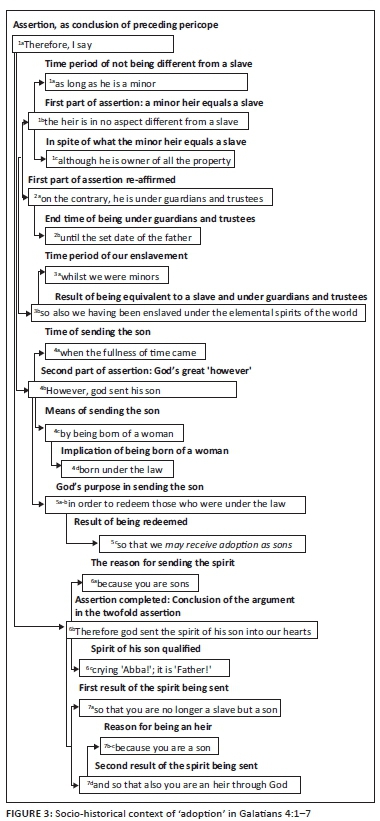

My understanding of the thought structure of Galatians 4:1-7 on macro-level can be represented in the following way:

The place of 'adoption' in the argument of Galatians 4:1-7 is that not only does God send his son to redeem believers from enslavement to the Law and from the elemental spirits of the world, but he also lifts them up as children by adoption (τὴν υἱοθεσίαν), so that believers are the heirs of God by the Spirit of Christ promised to Abraham. Determining the place of freedom in Galatians 4:1-7 centres around ἐπιτρόπους, οἰκονόμους, δεδουλωμένοι, ἐξαγοράσῃ and υἱοθεσίαν:

God sent his son, born of woman, that is, born under the Law, in order to redeem (ἐξαγοράσῃ) believers from slavery (δεδουλωμένοι) to the Law (ἐπιτρόπους and οἰκονόμους) and the elemental spirits of the world (τὰ στοιχεῖα τοῦ κόσμου), so that they could be set free and adopted as sons (τὴν υἱοθεσίαν) of God, the heirs of God's promise to Abraham, which is the Spirit of Christ.

Socio-historical context of 'adoption' in Galatians 4:1-7

As with the metaphor of παιδαγωγός (Gl 3:25) in the social context, Paul continues with the analogy of the imagery of the ἐπίτροπος [guardian] and οἰκονόμος [trustee] in this pericope (Gl 4:2). In the 1st century, Graeco-Roman social context, the exact function of the ἐπίτροπος was to manage the treasury, fields and cattle; but, in general, the ἐπίτροπος managed the household of a minor (νήπιός, Gl 4:1) until they attained maturity, including providing the minor with food and clothing and all that was necessary for their schooling and general well-being (Belleville 1986:61). The minor was theoretically the legal owner of his inheritance. However, the control of his property and his well-being were in the hands of the legal guardians, so that the minor could not act independently while he had not yet reached the age of maturity (see Figure 3).

Being ὑπὸ παιδαγωγόν [under a disciplinarian] is equivalent to being ὑπὸ ἐπιτρόπους [under guardians, Gl 4:2], which signifies a lack of freedom during childhood within the familia. The child's life and possessions are controlled and managed by others until the father determines that the child has reached maturity and at the appropriate time releases the child from the guardianship (Gl 4:2-4). Here, οἰκονόμοι [trustees] have to be understood as Graeco-Roman guardianship (Bartchy 1992:138; Goodrich 2010:265-273). There is some overlap in the duties of the ἐπίτροπος and the οἰκονόμος. The former is in charge of the monetary revenues, whereas the latter is designated as the agent of the estate (Belleville 1986:62). Although the tasks of the ἐπίτροπος and of the οἰκονόμος overlap, their spheres of applicability differ. The term οἰκονόμος is not used with reference to Roman inheritance laws, but as an administrative term with no apparent legal connotations. In this regard, Paul chose the term οἰκονόμος for describing a supervisor of slaves.

Paul's term for the personification of the Law (παιδαγωγός - Gl 3:23-25), as well as guardians and trustees (Gl 4:2), indicates a temporary control over human beings (De Boer 2011:241). Paul points out that while the son is under the charge of disciplinarians, guardians and trustees, he, like a slave, lacks the capacity of self-determination. Similarly, the Jew under the Law also lacks this capacity. The main theme of the analogy in Galatians 4:1-2 is that the time of the Law was not permanent: 'Now faith has come, ending the time of law'. Having been baptised into Christ (Gl 3:27), believers are now 'all children of God' (Gl 3:26). Therefore, after using παιδαγωγός (cf. Gl 3:24-25) as an image of the son being constrained temporarily by education and being taken care of (Oakes 2015:134), Paul shows another aspect of constraint with the function of responsible control of people and management of assets by using ἐπίτροπος and οἰκονόμος (Goodrich 2010:265-73).

Another socio-historical dimension of this pericope is the υἱοθεσία (adoption as son - Gl 4:5), which was a prevalent social institution in the 1st-century social context (Oakes 2015:138). However, the heavenly father has, through the Lord Jesus Christ, a more intimate relationship than the Roman emperors (national fathers) or the fathers in the households of Rome. Within the Graeco-Roman household, the will of the paterfamilias was absolute (cf. 7.1-3). In using such imagery, Paul's message to the Galatians is clearly indicated as non-negotiable.

Word study of important related concepts in Galatians 4:1-7

Adoption in Galatians 4:1-7 centres on ἐπιτρόπους, οἰκονόμους and υἱοθεσίαν

Ἐπιτρόπους (Gl 4:2): According to Louw and Nida (1996), ἐπιτρόπος belongs to two specific domains: (1) foreman (37.86) and (2) guide 36.5. The former can be defined as 'a person in charge of supervising workers or one who assigns work to the workers'. The latter has the meaning of 'a person who guides, directs and shows concern for - guardian, leader and guide'. Contextually, domain 36.5 (b) fits Galatians 4:2 best as it has the meanings of 'to guide and to help' or 'to help by leading' or 'to care for by leading', similar to the word παιδαγωγός (disciplinarian) in Galatians 3:24.

Οἰκονόμους (Gl 4:2): The word οἰκονόμος is located in the domain Household Activities (46.1-19) (Louw & Nida 1996). It functions in three sub-domains: (1) Manager (domain 46.4): 'One who is in charge of running a household'; (2) administrator (domain 37.39): 'One who has the authority and responsibility for something - one who is in charge of, one who is responsible for, administrator, manager' or (3) city treasurer (domain 57.231): 'One who is in charge of the finances of a city'. Contextually, domain 46.4 (a) and domain 37.39 fit Galatians 4:2: 'One who is in charge of running a household with responsibility for protecting assets of the heir'.

Υἱοθεσίαν: This word has already been studied (cf. 4 above)

Revelation-historical context of 'adoption' in Galatians 4:1-7

In the Old Testament Israel, as nation was freed from bondage and received the privilege of being the chosen son of God, as can be seen in the passages discussed earlier (cf. 6). Other passages in the New Testament that witness this perspective are found in John 1:12-13; 20:17; Romans 8:14; 2 Corinthians 6:18; Ephesians 1:5; 5:1; Philippians 2:15; Hebrews 2:10; 1 John 3:1-2 and Revelation 21:7.

The unique contribution of Galatians 4:1-7 to this revelation is that ransom is used as an image, with God sending his son, Jesus Christ, as a ransom to set all the believers free from being enslaved by the Law and the elemental spirits of the world. The result of this freedom is that they may receive the Spirit and be attested as sons (υἱοθεσία) and therefore be heirs of God.

The communicational goal of Galatians 4:1-7

The communicational goal of this pericope is to explain to the Galatians that the control of the Law was temporary, similar to the role of slaves with regard to the care and education of children in the household in preparation for their future inheritance. To demonstrate this, Paul employs the images of the guardian (ἐπίτροπος) and trustee (οἰκονόμος), whose temporary stewardship functioned exactly like the Gentiles' and Jews' enslavement under the Law. Therefore, if in the new changed circumstances, the Galatians committed themselves to observe the Jewish law, it would be similar to re-entering into slavery. Now, the time of slavery belongs to the past, because of the son born of a woman and born under the Law, so that believers can be free from those forms of slavery and, instead, be adopted as children into the household of God and inherit the blessing of the Spirit. Thus, Paul uses the word υἱοθεσία to remind the Galatian believers that they are no longer slaves but children of God and therefore heirs of God through his only son Jesus Christ.

Conclusion

Focusing on the rights of inheritance, the metaphor of believers as children of God can be seen clearly from previous sections leading up to the pericope of Galatians 4:1-7 (Gl 3:23-4:7). In 4:1-7, Paul envisions that, whoever is granted sonship by adoption, also gains inheritance.

From the perspective of the power of the adoptive father, he had full authority to ensure the rights of the adopted son. Paul uses the metaphors of adoption and inheritance within this pericope to demonstrate that God, as the father who is the head of the household with the absolute authority, is able to legally adopt sons into his household without adhering to the Jewish law.

According to the transaction of social advancement through adoption, the legal status passed from the father to the adopted son, requiring him to give up all rights to his original family. An adoptee had to commit to the responsibilities required of him as a son in his adopted family. All his previous debts were wiped out and the adoptee started a new life as part of his new family, honouring the name of his father. Therefore, the Galatians are transferred from being slaves, who do not belong to the family, to being adopted as children in the household of God through Jesus Christ. They are now free and have the privilege to be adopted as children and to become one in Jesus Christ within the household of their father.

Paul did not use the image of sonship in the Old Testament and in 1st century Jewish culture as a vehicle to convey the message of God's salvation (cf. 5-6). Rather, he turned to the concept of adoption as a son, which can be understood only within the 1st century Graeco-Roman social framework. By using adoption imagery, Paul demonstrates the reality of redemption for both Jews and Gentiles.

Acknowledgements

This manuscript stems from a published thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Philosophiae Doctor in the Theological Faculty of North West University in South Africa entitled 'Freedom in Galatians: A socio-historical study of the adoption and slavery imagery'. Supervisor: Fika J. Van Rensburg.

Competing interests

The author declares that no competing interest exists.

Author's contributions

I am the one writing this manuscript and being supervised under Prof. Fika J. Van Rensburg.

Ethical consideration

This article followed all ethical standards for a research without direct contact with human subjects.

Funding information

This article received no specific grant from any agency in the public, comercial or not for profit sectors.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are my own perspectives and do not necessarily reflect the official or position of any affiliated agency. Taiwan Graduate School of Theology, Taiwan.

References

Aristotle, 1926, Rhetoric, transl. J.H. Freese, Perseus Collection: Greek and Roman Materials, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, viewed 24 March 2018, from http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Aristot.%20Rh. [ Links ]

Aristotle, 1944, Politics, transl. H. Rackman, Perseus Collection: Greek and Roman Materials, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, viewed 14 March 2018, from http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0058. [ Links ]

Bartchy, S.S., 1992, 'Slavery as salvation: The metaphor of slavery in Pauline Christianity', Journal of Biblical Literature 111(2), 345-347. https://doi.org/10.2307/3267563 [ Links ]

Belleville, L.L., 1986, '"Under law": Structural analysis and the Pauline concept of law in Galatians 3:21-4:11', Journal for the Study of the New Testament 9(26), 53-78. https://doi.org/10.1177/0142064X8600902604 [ Links ]

Betz, H.D., 1979, Galatians: A commentary on Paul's letter to the churches in Galatia, Fortress Press, Philadelphia, PA. [ Links ]

Braaten, L.J. 2000. 'Adoption and adoption imagery', in D.N. Freedman, A.C. Myers, & A.B. Beck (eds.), Eerdman's dictionary of the Bible, pp. 21-22. Grand Rapids, W.B. Eerdmans, MI. [ Links ]

Burke, T.J., 2006, Adopted into God's family: Exploring a Pauline metaphor, InterVarsity Press, Downers Grove, IL. [ Links ]

Byron, J., 2003, Slavery metaphors in early Judaism and Pauline Christianity: A traditio-historical and exegetical examination, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen. [ Links ]

Cicero, M.T., 1891, The orations of Marcus Tullius Cicero, vol 1: Orations for Quintus, Sextus Roscius, Quintus Roscius, against Quintus, Caecilius, and against Verres, transl. C.D. Yonge, Perseus Collection: Greek and Roman Materials, G. Bell and Sons, London, viewed 20 April 2018, from http://lf-oll.s3.amazonaws.com/titles/570/0043-01_Bk.pdf. [ Links ]

De Boer, M.C., 2011, Galatians: A commentary, John Knox Press, Louisville, KY. [ Links ]

Ferguson, D.S., 1986, Biblical hermeneutics: An introduction, John Knox Press, Atlanta, GA. [ Links ]

Goodrich, J.K., 2010, 'Guardians, not taskmasters: The cultural resonances of Paul's metaphor in Galatians 4:1-2', Journal for the Study of the New Testament 32(3), 251-284. https://doi.org/10.1177/0142064X09357677 [ Links ]

Goodrich, J.K., 2013, 'From slaves of sin to slaves of God: Reconsidering the origin of Paul's slavery metaphor in Romans 6', Bulletin for Biblical Research 23(4), 509-530. [ Links ]

Harrison, J.R., 2011, Paul and the imperial authorities at Thessalonica and Rome: A study in the conflict of ideology, Mohr Siebeck, Tuebingen. [ Links ]

Heim, E.M., 2017, Adoption in Galatians and Romans: Contemporary metaphor theories and the Pauline Huiothisia metaphors, Brill, Boston, MA. [ Links ]

Holland, T., 2004, Contours of Pauline theology: A radical new survey of the influences on Paul's biblical writings, Mentor, Fearn. [ Links ]

Krueger, M.T. & Watson, A., 1985, The digest of Justinian, v. 1, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, PA. [ Links ]

Lakoff, G. & Johnsen, M., 2003, Metaphors we live by, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL. [ Links ]

Leith, J.H., 1973, Assembly at Westminster: Reformed theology in the making, John Knox, Atlanta, GA. [ Links ]

Lindsay, H., 2009, Adoption in the Roman world, Cambridge University Press, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Louw, J.P. & Nida, E.A., 1996, Greek-English lexicon of the New Testament: Based on semantic domains, 2 vols., United Bible Societies, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Matthews, K.A., 2005, 'Genesis 11:27-50:26', in The New American Commentary: An exegetical and theological exposition of holy scripture, v. 1B, Broadman & Holman Publishers, Nashville, KY. [ Links ]

Oakes, P., 2015, Galatians, Paideia Commentaries on the New Testament, Baker Academic, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Peppard, M., 2011, The son of God in the Roman world: Divine sonship in its social and political context, Oxford University Press, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Rhoads, D., 2004, 'Children of Abraham, children of God: Metaphorical kinship in Paul's letter to the Galatians', Currents in Theology and Mission 31(4), 282-297. [ Links ]

Scott, J.M., 1992, Adoption as sons of God: An exegetical investigation into the background of yiothesia in the Pauline Corpus, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen. [ Links ]

Seneca, L.A., 1974, The Elder Seneca: Controversiae, books 1-6, transl. M. Winterbottom, Heinemann, London. [ Links ]

Seneca, L.A., 2009, Seneca: De clementia, S. Braund (ed.), Osford University Press, London. [ Links ]

Soskice, J.M., 1985, Metaphor and religious language, Clarendon, Oxford. [ Links ]

Strabo, 1924, The geography, transl. H.L. Jones, Perseus collection: Greek and Roman Materials, Harvard University Press, MA, viewed 02 May 2018, from http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.01.0198. [ Links ]

Stuart, D.K., 2006, The New American Commentary, v. 2: Exodus, Broadman & Holman Publishing Group, Nashville, TN. [ Links ]

Tsang, S., 2005, From slaves to sons: A new rhetoric analysis of Paul's slave metaphors in his letter to the Galatians, SBL, 81, Peter Lang, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Van Der Watt, J.G., 2000, Family of the king: Dynamics of metaphor in the Gospel according to John, Brill, Boston, MA. [ Links ]

Van Rensburg, F.J., 2000, 'Decor or context? The utilization of socio-historic data in the interpretation of a New Testament text for preaching and pastorate, illustrated with First Peter', In die Skriflig (Verbum et Ecclesia) 21(3), 564-582. [ Links ]

Van Rensburg, F.J., 2005, 'Metaphors in the soteriology in 1 Peter: Identifying and interpreting the salvific imageries', in J.G. Van der Watt (ed.), Salvation in the New Testament: Perspectives on Soteriology, pp. 409-435, Brill, Boston, MA. [ Links ]

Van Rensburg, F.J., De Klerk, B.J., De Wet, F.W., Lamprecht, A., Nel, M. & Vergeer, W., 2015, Conceiving a sermon: From exegesis to delivery, Potchefstroom Theological Publications, Potchefstroom. [ Links ]

Waltke, B.K., 2001, Genesis: A commentary, Baker Academic, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Wenham, G., 'Genesis 16-50', in John D.W.W. ed. Word Biblical Commentary, v.2. Dallas, TX: Word Books Publisher. [ Links ]

Westermann, C., 1987, Genesis, T&T Clark, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Chih Wei Chang

isa1214@gmail.com

Received: 06 Aug. 2020

Accepted: 24 Feb. 2021

Published: 30 Apr. 2021

1. Freedom in Galatians: A socio-historical study of the adoption and slavery imagery, Fika J. Van Rensburg, Faculty of Theology of North West University, 2019.

2. I use the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) to do the exegeses and utilise the periscope structure used by De Boer (2011).