Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

HTS Theological Studies

versión On-line ISSN 2072-8050

versión impresa ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.77 no.3 Pretoria 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v77i3.6585

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

'I fish because I am a fisher': Exploring livelihood and fishing practices to justify claims for access to small-scale fisheries resources in South Africa

Samantha Williams

Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa

ABSTRACT

In South Africa, claims for and access to natural resources are deeply embedded in people's histories, identities and livelihood experiences. As in the case of land, access to and rights over fisheries resources is a highly contested issue where individuals and communities have equated such rights with human rights. This article considers the role of cultural and livelihood experiences of fishers in articulating claims for accessing fisheries resources. Individual and oral history interviews conducted with fishers and community members demonstrate how historical (and contemporary) organisation of the fishery contributes to local livelihoods and social cohesion and how formal management practices have not considered these rights. This study discusses how fishers as a community have endured systematic dispossession and exclusion, framings of fisher identity, livelihood activities and how cultural significance of the fishery takes centre stage when claims for access to fisheries resources were made. This article concludes by highlighting how fisher activities, identity and social relations, which are embedded in this system have challenged formal management approaches and altered a trajectory in fisheries management and conservation planning.

CONTRIBUTION: This research draws inspiration from the Ebenhaeser community on the Olifants River estuary to demonstrate the intrinsic value of this traditional small-scale fishery to this community. This study contributes to the discourses on complex social-ecological systems and how social values underpin these systems.

Keywords: fishing; access; claims; identity; values; livelihoods; South Africa.

Introduction and background to the study

In contemporary South Africa, it is acknowledged that some of the country's most persistent tensions have revolved around access to, and claims for, natural resources (Tropp 2006:1). Historically, discriminative policies and processes resulted in the marginalisation, dispossession and exclusion of people from natural resources and resource-rich areas, which contributed to sustaining their livelihoods (Fabricius 2004:5; Wynberg & Sowman 2007:786). In some instances, these measures were forcibly imposed on individuals and communities to make way for various conservation objectives that took precedence over community livelihoods (King 2007:208). This for many resulted in the loss of agricultural land and access to coastal and fisheries resources.

Therefore, the policy reforms by the democratic government of South Africa aimed to address past injustices and amongst others ensure fair and equitable access to natural resources (Du Toit 2013:18; Jacobs & Makaudze 2012:584). Governance of natural resources advocated for holistic and participatory approaches based on human-rights principles (Sowman 2011:305). As a result of years of dispossession and inequality a call for massive reforms in society and in the policy, environment was necessary. Whilst the intentions of policy reforms may be clear, experience has shown that implementation is challenging (Sowman 2011:306; Weideman 2004:232). Consequently, discontent (through protest or legal action) has been observed between those who depend on natural resources and bureaucratic systems tasked with its management. Of particular relevance in this study is the small-scale fisheries sector where issues of access to fisheries resources and sustainability of fisheries systems have been contested. The introduction and implementation of new fisheries policies post-apartheid were only the beginning of a long-reform process that is still continuing (Williams 2013:56). The promulgation of a small-scale fisheries policy in 2012, for example, has seen limited progress in implementing its goals. The policy framework calls for redress, is guided by principles of equity and outlines the need for cooperative governance in small-scale fisheries. It further calls for the sustainable distribution of fisheries resources with the aim to reduce poverty and promote food security. Whilst its development over a 5-year period was significant and involved fishing communities, these novel contributions have not been aligned with implementation activities. This has left fishers and their communities with limited tangible benefits and the continued need to assert their claims to fisheries resources.

In this research, the aim is to demonstrate how claims for fisheries resources are embedded in cultural practices, people's identities and contemporary livelihood activities. It draws on Ribot and Peluso's (2003) access theory to understand the 'mechanisms' that are harnessed by people to justify such claims. According to their articulation of access, the authors call for a shift away from the commonly held notions of access. They argue that, in property theory, for instance, access is defined as the right to benefit from things whilst in their definition, access is seen as the ability to benefit from things (Ribot & Peluso 2003:154). They outline this differentiation by highlighting that:

Someone might have rights to benefit from land but may be unable to do so without access to labour or capital. This would be an instance of having property (the right to benefit) without access (the ability to benefit). (p. 157)

In this example, labour and capital would be considered as the mechanisms that enable abilities and, hence, allow benefits to be derived. They draw attention to the ability-enabling factors and maintain that 'access remains empirical'. This conceptualisation of access maintains that people are able to gain and benefit from natural resources through 'direct' (rights-based) and 'indirect' (structural and relational) elements of access. The 'direct' element, could entail access through property rights or extra-legal measures and is viewed as the first level of an ability to benefit from a resource. The 'indirect' elements that include knowledge, technology, capital, labour, markets, authority, identity and social relations amongst others constitute the second level of abilities that may facilitate access. In applying and conceptualising access in small-scale fisheries from this vantage point, the analysis provided here will demonstrate how fishers acknowledge formal rights, but that other elements that include aspects of fisher and community identity are of equal if not greater importance in justifying claims for access to resources. It therefore draws attention to social (cultural and traditional) relations, identity and contemporary livelihood activities.

In order to demonstrate how social and livelihood activities are drawn on, this article will report on two processes. It will highlight how fisher livelihoods and conservation objectives are not easily reconciled. Firstly, by using a small-scale fishery as case study it outlines that where the case for protection of natural resources was made it happened with science-based conservation values. Secondly, and in contrast, fishers not only based their claims to access fisheries resources on livelihood considerations (which extend beyond economic gains), but also drew on traditional and cultural mechanisms to support such claims. Their intimate connection to fishing is expressed in how they perceive their identity and lived experiences as motivations to substantiate access.

Overview of fishing at the Olifants River estuary

Fishing is an age-old activity that has provided sustenance to human populations since time immemorial. The role and tradition of fishing at the Olifants River estuary for Liza richardsonni (mullet) or harders (See Figure 1) as it is known locally, can be traced back to the 1800s. Archival records suggest that there is evidence that harders were harvested by indigenous communities inhabiting the Western Cape coastal regions even before the arrival of Europeans (De Villiers 1987:851).

It is well recognised the world over that fishing activities for many communities sees strong cultural and traditional links spanning many generations, and its value is seen beyond the means of earning a living (i.e. economic values) (Béné & Friend 2011:121; Johannes 1981:9). Whilst fishing takes place at sea (or the coastal or estuarine environment, etc.), other activities related to fishing such as boat and net maintenance, the selling and trading of fish, etc. take place on land (Urquhart, Acott & Zhao 2013:1). Therefore, the activities associated with fishing create a particular identity or characterise an area as a result of these activities.

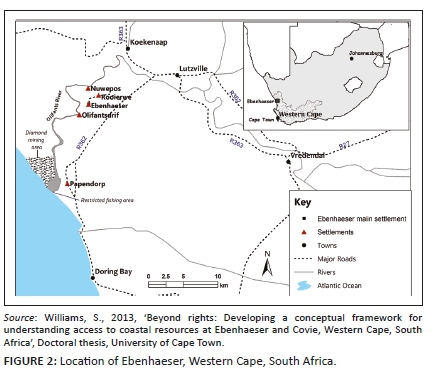

Ebenhaeser is a rural village situated on the lower reaches of the Olifants River on the West Coast of South Africa (See Figure 2). Historically, the Ebenhaeser community lived on fertile land near present day Lutzville (See Figure 2), where a Rhenish mission station was established. Inhabitants had access to fresh water from the Olifants River and were primarily engaged in farming activities and fishing to contribute to their livelihood activities. In 1925, the Ebenhaeser Exchange of Land Act No. 14 saw the removal and resettlement of people from this area to where Ebenhaeser is situated today. After the removal, people made distinction between the 'Old Ebenhezer' and the new area, Ebenhaeser where they were resettled (Williams 2013:150). The 'new' area had less fertile land and the available water was saline, so the potential for farming activities was limited (Sowman 2017:27). Fishing, which already played a role in sustaining livelihoods, became even more important and this activity continues to play an important role in contributing to those livelihoods dependent on it.

Community members living in the area consist of descendants of families who were evicted during the land exchange of 1925. After relocation to the lower reaches of the river, families who were situated at the settlements of Papendorp, Olifantsdrift, Rooi-erwe, Ebenhaeser and Nuwepos (See Figure 2, all collectively form part of Ebenhaeser) intensified their fishing activities to sustain their livelihoods (Sowman et al. 1997:181). Fishing is undertaken by men with women playing a role in pre- and post- harvesting activities (Williams 2013:143). Whilst fishing activities for these communities have largely been contained to the estuary, fishers from the Ebenhaeser settlements historically also travelled and spent time fishing at the neighbouring coastal town, Doringbaai (approximately 20 km away) whilst many others worked in coastal towns along the West coast of South Africa. At the estuary, the main methods of capture have been seine and gillnets and fish are either marketed fresh or in the case of vast surplus catches is dried with salt and sold as bokkoms (cured fish) (Williams 2013:145). However, the method of capture through the use of gillnets has been cited as a global concern especially in the light of concerns for overexploited linefish bycatch (Hutchings & Lamberth 2002:227). This method which is described as a passive form of fishing sees nets (either monofilament or braided nylon nets) deployed in the water in the hope that shoal fish will swim into the net (Hutchings & Lamberth 2002:229). Fishing at the Olifants River estuary is solely for the harvesting of harders and occurs in the lower 15 km of the estuary where gillnets are set from the small rowing boat. These nets are allowed to drift with the current and are checked regularly (Carvalho et al. 2009:120). Forty-five formal permits are issued annually by the fisheries authorities and each permit holder may work with one crew member (Sowman 2003). This brings the number to 90 legal harvesters that may fish at the estuary (Williams 2013:197). The river mouth is closed to fishing and very limited fishing occurs during winter months.

Livelihoods and conservation at odds: The phasing out proposal and development of the Olifants estuary management plan

Whilst the activity of fishing presents various challenges, it is an important source of food security and income for many communities across the world (Béné 2006:1; Purcell & Pomeroy 2015:3). The community of Ebenhaeser has been dependent on the Olifants River estuary for over a century (Sowman 2017:27). However, as highlighted here gillnet fishing has been an area of concern in South Africa. This is because gillnet activities have largely been prohibited in estuaries in South Africa, making Ebenhaeser an exceptional case where these practices are still occurring. In the past, however, motivations have been put forward for its closure and in 2005 a policy directive by the former Department Environmental Affairs and Tourism (DEAT) branch, Marine and Coastal Management (MCM), called for the phasing out of gillnet activities at the Olifants River estuary. This proposal was met with opposition from the community and others working closely with the community. There was uncertainty regarding existing rights and the lack of clarity on how the proposal will impact community livelihoods (in the absence of alternative livelihood activities) that prompted the community to challenge fisheries authorities.

Another key process that threatened to end fishing practices at Ebenhaeser was the development of a management plan for the estuary. The development of the Olifants Estuary Management Plan (OEMP) over the period 2007-2012 was another process that first contributed to resistance and later saw a redrafting of management and conservation proposals for the area. The major area of contestation initially involved the proposed declaration of a no-take marine protected area (MPA) that would include fishing areas that the community used. This process, however, was challenged by the fishers and their community and over five-year period various activities that included drafting letters to authorities at ministerial level called for the need to participate equally in any planning and conservation process for the area. The community emphasised for their fishing rights to be respected and that certain protective measures be put in place. Another stressed aspect was that conservation of the area should consider the principles of co-management and local level partnerships (Sowman 2017:31). Key factors and areas of contestation included agreement on how to move forward and how management objectives and approaches should be framed (Williams 2013:211). There were periods of limited to no activity that occurred in working towards a revised OEMP and communication occurred largely between the communities' legal representatives, management authorities, fisher representatives and other research partners involved in the process. The focus of these discussions was on how the fishers' livelihood needs could be accommodated within a conservation framework for the estuary.

Methodology and design

The research phases of this study occurred over the period 2009-2011. The researcher has however conducted research on various aspects of the fishery since 2006. Familiarity with the context and members of the community were therefore well established. The data used in this study were collected from 68 semi-structured interviews that were conducted with fishers and community household heads. A semi-structured interview guide was used that ensured that participants were asked the same questions. Interviewees were asked about their family and community life, years and involvement in fishing activities, dependency on fishing and incomes derived and their opinions and perceptions about conservation management of the estuary and natural resources. All interviewees were approached personally by the author and their participation was requested. In addition, two focus group meetings and two oral history interviews are included in this analysis. The emphasis during the oral history interviews was not only focussed on the interviewee's lives, but discussions ranged from specific information about the interviewee's upbringing, community life, historical events related to access to and fishing activities and, in some interviews, perceptions about current fisheries and management processes. One of the oral history interviews highlighted here was conducted in collaboration with members from the legal entity that represented the community at the time. Permission to use this interview was obtained and is highlighted in the Results section.

The interviews ranged from one to two hours. Interviews were transcribed (and translated) and data were grouped into themes. Themes which included historical aspects, values associated with the fishery, identity and contemporary livelihood dependency were the most apparent. These themes were therefore prioritised and included in this analysis as key mechanisms for claiming access to fisheries resources.

Discussion on the findings

In Ribot and Peluso's (2003) access framework, the role of formal rights is highlighted and recognised as a mechanism of access. Rights to harvest fisheries resources at the Olifants River estuary is a regulated activity and therefore formal rights are acknowledged by the state and the fishers. Whilst the role of formal rights is relevant and important for access in this particular case, other factors which may be equally or of greater importance for claiming and maintaining access are discussed. These aspects are related to contemporary and traditional use and practices and how people articulate and express the connection they have to fishing activities. These aspects are captured in the responses and narratives of fishers and community members and used as justification to access fisheries resources.

It is more than an income

An important aspect that was dominant from the survey results (n = 68) was the cultural and traditional attributes of the community's fishing practices. This was expressed when fishers spoke of how they grew up and started fishing at a very young age. During interviews, fishers shared information about their family histories and how they regarded fishing as part of their culture ('we were raised from the river, that is why we know nothing else' [Fisher 1, 2009, Olifantsdrif]; 'you were born next to the river, baptised in the river and you make your life from the river' [Fisher 2, 2009, Olifantsdrif]). Forty fishers included in the survey stated that it was as a result of being taught by a father, uncle, brother or being part of the fishing community that got them started. In addition, they would proudly share their first experiences when they started fishing on the river and sea and the skills that one acquires as a fisher:

'A fisher should know that sometimes things will be good, but there might be times when you do not catch anything, he should know his equipment and should know what capabilities he possesses.' (Focus group session 1 with eight fishers, 2009, Papendorp)

Based on the survey results, 11 respondents added that contributing to the household income and food security were strong factors that played a major role in pursuing fishing. The link that fishers made with their birthplace and how as a member of a fishing community they are able to exercise what they considered as a gewoonte reg (birth right) echoed throughout many interviews. Responses that captured these sentiments were expressed as follows 'because my life is here, I mean, I love fishing, that is what my life is about' (Fisher 3, 2009, Ebenhaeser). Furthermore:

'[O ]ur parents and fathers were all fishermen, we all grew up here, we lived like this, we all grew up like this from generation to generation, it comes from our forefathers.' (Fisher 4, 2009, Ebenhaeser)

Whilst questions about the years spent actively fishing saw respondents citing their childhood as the actual starting date(s) for fishing, others simply stated that because they grew up in a fishing community and that it was just natural to go for fishing (Fisher 5, 2009, Ebenhaeser). A fisher who spoke of his years fishing at the Olifants River estuary and elsewhere at sea added that fishing is something that is entrenched in his being. He added that 'even if a man goes away for a few months or years, he will always come back to the sea' (Fisher 4, 2009, Ebenhaeser). These responses could be viewed as some of the motivations that are responsible for fishers doing what they do and the value they attach to their activities.

The data collected through the questionnaires (n = 68) confirmed that the most important income generating activity (source of income) was derived from fishing activities (54%) and government grants (29%) being the second most important. Employment (12%), seasonal (3%) and part-time work (2%) made up the other limited opportunities available to generate an income. Other responses about the role of fishing were associated with the instant benefits that fishing has to offer. Fishers expressed this when they added that if they need to provide food or some cash, then turning to fishing would be able to satisfy those needs (Focus group session 2 with 10 fishers, 2009, Olifantsdrif). Whilst many households in Ebenhaeser are dependent on a variety of sources or activities to generate an income, fishing remains a critical source both in terms of income and as a source of food security for this community (Louw 2020:34; Sowman 2017:28). As a rural community, where employment opportunities are few, the role of fishing is regarded as primary and as one young fisher remarked that 'it is important because there is nothing to do here. Even young people are interested as there are no employment opportunities' (Fisher 6, 2009, Papendorp). During interviews and informal discussions with some of the younger fishers and community members many would reiterate the point of no employment opportunities and hence their dependency on fishing as the only livelihood option.

Community reciprocity and social cohesion

The fishers usually set out in the early evening on a fishing trip and they stay out all night. Make shift shelters or skerms (as it is locally known) are then constructed on the banks of the river. The skerms area would serve as a meeting place or where they would sleep until morning when they return back to the fishing settlements (Fisher 7, 2009, Olifantsdrif). As part of their formal rights conditions, fishers are allowed to work in pairs.1 By having a fellow fisher with you not only provides assistance during fishing trips but also a companion that could assist should an emergency arise. During an interview it was explained that the relationship between the fisher and bakkie maat or permit holder and the non-permit holder is reciprocal and beneficial (Fisher 2, 2009, Olifantsdrif). This is so as the fisher without a permit is able to work with the permit holding fisher and the permit holding fisher has the benefit of assistance. Both therefore engage in harvesting and/or in selling where possible and the benefits are evident for both fishers.

When fishers return from a fishing trip and a good catch was caught, arrangements are made to sell the fish fresh at nearby towns or to community members. When a fishing trip resulted in some fish, but not a significant amount to sell, it will most often be consumed at home. During interviews it was also highlighted by community members that even households without a fisher are able to get fish from neighbours if they needed it and fish is a lifeline in times when there are no other food options (Community member 1, 2009, Olifantsdrif). These community activities and characteristics are not unique to fishing communities in South Africa. In many developing countries poor and rural fisher communities are considered amongst the poorest and most marginalised sectors of society (Kalikoski et al. 2019:122). Therefore, by being associated through social ties and/or investing in community and social relations strengthens individuals' position in terms of being able to benefit (Berry 1989; Pomeroy & Andrew 2010) even when they are unable to physically access resources.

Fishing is undertaken by men, with women playing a key role in pre- and post-harvest activities. Some of these activities include making sure that the fisher is prepared before setting out on a fishing trip. In relation to the role of women in fishing, a community member added that, historically, women and children also assisted with tasks such as packing fish in baskets or helping with the selling and drying of fish. Locals in Ebenhaeser called the process of assisting with post-harvesting activities vis koelie (Community member 2, Papendorp). During an oral history interview in Olifantsdrif, one of the oldest women in the community and her brother (Oral history interview 1) shared their family history and memories of their father, who was a fisher and well-known net-maker from Ebenhaeser. In the interview both interviewees mentioned how as children they had to assist in the household, the sons with the fishing activities and the women with netmaking. The interviewee (woman) added that even though the women worked within the home environment she also needed to help sew nets for her father. The sons were predominantly involved with fishing and attended to netmaking occasionally and therefore the children and women in the household were especially involved in this activity. The role and contribution of women and children therefore further extended the social activities and involvement within this small-scale fishery system and this is still relevant today.

An intimate connection: How the tradition of fishing contributes to community identity

The oral history interviews were conducted amongst senior community members. A key interest here was to gather information on historical fishers who still lived in the area; the species harvested; the equipment used; whether local rules guiding the fishery existed, and, if any, how these were exercised by the fishers; the local fisher knowledge that existed about the fishery and the history of all of these activities.

An interview with one of the oldest members of the Ebenhaeser community, the late Mr Joseph Taylor (Oral history interview 2), provides a rich account of the importance of the Olifants River estuary and its resources for the community, their culture and identity. This interview emphasised the long history and tradition of fishing at the site and references were made to key processes that historically occurred and shaped access to natural resources here. Whilst Mr Taylor was the main interviewee in this particular interview, several older community members were present during the interview. This interview was conducted in collaboration with members of the community's legal representatives and permission was sought to include it in this analysis.

Extracts from the direct transcribed interview are provided here in English.

Oral history interview with Mr Joseph Taylor

Born on 06 October 1935 at Ebenhaeser Mr Taylor was regarded by many community members as an authority figure to speak about the history of Ebenhaeser. The interview commenced with the interviewee speaking about 'Old Ebenezer' and his memories thereof. He stated that the land was beautiful and fertile and when the white people saw that they decided that they wanted the land, as the Old Ebenezer had the best and most fertile land. He described the Old Ebenezer as the area with green with beautiful vineyards. This today, as highlighted here, is current day Ludzville - a productive wine-cultivating area. The group present confirmed that stories told by older community members indicated that the man who divided the land and gave it to the white farmers was known as 'old Ludtz' - the superintendent at the time. The interviewees continued and mentioned that residents from Old Ebenezer always told people (the white people) that the place called Ludzville is Ebenezer. This is how the 'land exchange' of Ebenezer to Ebenhaeser was explained.

The main interviewee remarked that, from his earliest memories he could recall that his father worked for white farmers at Ebenezer, but that he also grew vegetables on a small piece of land he owned. His father passed away whilst he was still young. When asked if he knew stories about Old Ebenezer, the people, their activities and livelihoods, he responded by saying that his mother was a woman who never went to school, could not read or write, but could speak English and would tell them stories about the old days. The interviewee shared how his mother told them about people of the community who tilled the land whilst there were others involved in fishing. According to the interviewee, when people were moved to Ebenhaeser, where the land was less fertile they went for fishing more frequently as people no longer had land on which to work. He added by saying that fishing is so important to the community and that the resource had always been in such abundance and could never be depleted. He emphasised this by stating:

The Olifants and its waters, the beautiful land and the fish, it is inseparable from each other. It is one process. The river runs like a vein through this area. The activity of fishing, this activity of almost 100 years. Fish and bread is the staple food of our people. Right next to the river's edge, high-water mark at Papendorp and all along the coast line. Two little fish and 5 loaves of bread used to feed so many people in the olden days and it is still on tables today as the food that tastes the best. How can they restrict the large amounts of people and want to take away the source of life and enjoyment? We refuse to lose this value. We cannot let go of our rights and I underlined that, that we cannot let go of values accumulated over so many years in return for a bowl of lentil soup. We were left behind by apartheid. We have been identified as the ones left behind, no, we were left behind. (Williams 2013:150-151)

As he grew up in a fisher community, the interviewee stated that he is a fisherman. He mentioned that he had worked for 24 years at sea and on the river and was able to raise 11 children. The interview progressed to discuss how fishing activities were organised during the earlier years at Ebenhaeser. It was observed by community members present that there was 'order and respect' (or local rules) amongst the fishers. When asked to provide examples of what they meant in terms of 'order and respect', the group recalled three unwritten 'rules' that were known by all. The first was that there was no fishing on Sundays as it was devoted to church. However, in the afternoon, the fishers could launch their boats and head to the baken [beacon], where there was a small island. When the first skuit [boat] or fisher arrived at the island, he would be 'the first boat'. The first boat arrangement was a local practice that became a second rule to how fishers would organise their fishing activities. Everyone who arrived after the first boat would line their boats up accordingly. The first boat would therefore first set out when the new week of fishing commenced. This arrangement was a practice that the fishers knew and respected and that no one would disregard it or set a net before the first boat went out. Whilst there were no direct benefits to this rule, it was a local norm that the fishers observed.

When a question was posed about whether there might have been an incident where someone may have ignored any of the rules, to this the response was unanimously no. The main interviewee maintained that everyone respected each other, but if there was a dispute amongst the fishers, this would be reported to the church. During the interview, it was noticed that being reported to the church was a scandal and when the elder members of the church spoke it was harsh words. All interviewees confirmed that the reprimand by the church was so harsh, they might as well have whipped you. A third unwritten rule amongst the fishers was that fishers were not allowed to secure nets from one river bank to the next as it would result in the river being 'closed off'. The fishers believed that this would disturb the flow of the river and the fish. It was added that if the river was 'closed off' with a net, then the next fisher might not be able to get a good catch.

From this oral history account, several aspects are worth weighting. Firstly, the resource in question: fish - or, more specifically, harders being harvested. Perceptions about the resource's sustainability were that the resource was in abundance and that the fishermen would never be able to compromise its sustainability and availability. This is a sentiment that was shared by other fishers in the community (Fisher 8 & 9, 2009, Olifantsdrif). Secondly, the communities' long history and dependence on fishing and how people's livelihoods and food security are dependent on fishing was prominent. A question posed by the main interviewee asked how people could be restricted from fishing if this is what they are depended on for their livelihoods and enjoyment. Thirdly, it was emphasised that the community need to safeguard their rights. There was a shared perception amongst those present that as a community, they were forgotten under the discriminative apartheid government and they feared that their community was not considered in management decisions affecting the Olifants River estuary.

Apart from the account of rules governing the fishery in other interviews fishers maintained that there are 'unwritten rules' or ways in which this fishery is governed (Fisher 2 & Fisher 10, 2009, Olifantsdrif). This is primarily based on respect for each other and their activities. In formal management meetings, fishers continuously called on authorities to recognise these aspects and organisation of the fishery (Williams 2013:223). Based on their historical links to the area and their activities, fishers and community members believed they had a right to access resources and a responsibility to the future generation to sustain their fishing practices. Comments from interviews emphasised this point about sustainability 'you only take what you need' and 'you do not fish for juveniles' (Focus group session 1 with eight fishers, 2009, Papendorp). This is how fishers and community members believed they contribute to the resource sustainability. During the collaborative oral history interview, members of the community stressed that they wanted to underline that they have legitimate rights that needed to be acknowledged. It was also important to emphasise their communities' historical use and value of the Olifants River estuary as they believed that it could provide the necessary evidence to support a legal argument if litigation was necessary.

Conclusion

When certain management proposals suggested the closure of the gill-net fishery at the Olifants River estuary the fishers and their community emphasised their traditional links and livelihood activities as a means to demonstrate and strengthen their claims for access. From a community perspective these references are legitimate ground for ensuring continued access. From this study, it is apparent that reference to fishing is an inherent part of this community's identity and livelihood holds value for this community. When confronted with the potential threat of closure of the estuary and restrictions on their fishing activities, this community not only vehemently opposed these proposals by voicing these in meetings but also actively engaged in research activities that would emphasise their dependence on this fishery system. What this analysis has aimed to demonstrate is that this dependency, which extends beyond economic values, is firmly rooted in people's history, their individual and shared identity as a community and their aspirations to maintain the practice of fishing for future generations.

Fishing in this particular context is a formalised activity and has limitations on the number of people who can 'legally' harvest resources. However, community members regard their proximity to the resource and their historical and community lineages as their 'user rights'. In this context although, formal recognition is only given to those individuals who are legally allowed to fish and 'community user rights' (or claims thereto) are not formally recognised. It is argued here that in case such claims are made, it demands contextualisation and acknowledgement. Whilst South Africa has made significant progress in developing policies to address environmental priorities, many challenges still hinder progress in ensuring that rights (actual or perceived) to natural resources are understood in the context that it is exercised. Furthermore, where government has been slow to implement policies (that aim to uplift communities), greater accountability should be shown in this regard. This would include the role that local managers and government departments have to play in ensuring that principles and plans outlined in policies address the needs and values of small-scale fisher communities. By working with communities this could contribute to sustainable use and management of the fishery system as a whole and ensure that poverty is addressed and food security options are enhanced.

In terms of developing a management plan at the Olifants River estuary, varying degrees of change was observed throughout the process. As a result of not accepting the initial OEMP, there was strong motivation from the fishers to develop community-based management proposals for the estuary. Moreover, with emphasis being placed for greater representation in management meetings, a local fisher representative was elected as co-chairperson of a forum that was established for the estuary (Fisher 11, 2009, Olifantsdrif). Furthermore, fishers demanded that emphasis should be placed on ensuring that conservation objectives are balanced with livelihood integrity. Berkes (2010:492) added that ensuring synergy between social and ecological systems is critical to understanding and ultimately achieving sustainability in fishery systems. The fact that proposals were tabled to declare areas of the estuary as protected in the absence of alternative livelihood options for fishers speaks of the value that scientific approaches still hold in natural resource management. Where imbalances between science-orientated approaches and local livelihood activities exist, this will undermine attempts to sustainably co-manage fishery systems. It will furthermore delay efforts to implement policy objectives and efforts to govern fishery systems in a holistic manner. Such imbalances also have implications or the potential to threaten constitutional rights, which include the right to food security, exercising cultural practices and securing a livelihood. Where future attempts are made to sustainably govern such fishery systems, it is paramount that scientific objectives are balanced with livelihood considerations.

Whilst no formal litigation action resulted from the OEMP process, notable achievements were that the process was challenged and that it was agreed that the concerns and livelihood aspects of the fisher community of Ebenhaeser needed to be addressed in a revised management plan. The outcomes in Ebenhaeser have therefore seen success for the local fishers in terms of the recognition of their livelihood activities and emphasis on a more participatory approach to fisheries management (Williams 2013:192). However, the contemporary socio-economic realities and needs of communities such as Ebenhaeser have seen less attention being focussed here. With high levels of poverty, absence of economic and social development in the area and dependence on government social support, fishing remains a critical part of livelihoods and also an important source of food security (Louw 2020:57; Williams 2013:198). A recent study by Louw (2020) again emphasised this dependency and further highlighted how market-related challenges and factors impede fishers' participation in the value chain. The need for access to fisheries resources therefore remains important but with changing environmental conditions (Sowman 2017:27) and certain months resulting in very poor catches, these factors are (and will likely continue) to impact fishing activities.

In this article, attempts have been made to present a deeper understanding of people's engagement with fisheries resources in order to demonstrate their links and values to this system. The focus has also placed emphasis on the perspectives of people and to provide context as to how individuals articulate the values and claims they make to fisheries resources. In addition, in this case people have developed precepts about the resources that they utilise, which Meinzen-Dick and Nkonya (2007:6) added provides a basis for observing obligations towards the resource and its sustainability. In this study, these notions of obligation were evident when fishers spoke of their own sustainable fishing practices, thus contributing not only to conservation but also to preserving their practices for future generations.

In many developing countries and in South Africa, the need for equity and access to natural resources demonstrates (see e.g. Jentoft 2003; Nelson 2010; Shackleton & Shackleton 2004) how natural resources benefit local livelihoods. Experience and research have also shown how management, policies and implementation of these have - in some instances, been slow or misguided. By highlighting the processes and outcomes from this study, it is apparent that - despite the development of progressive policies that speak of equity, upholding or enhancing rights and greater access to natural resources - the issue of rights (whether actual or perceived) remains an area of contestation. From the position of local fishers and their community, people draw on traditional and livelihood use of fisheries resources as a way to justify and legitimise access. These justifications are significant in terms of recognising people's rights to food and livelihood security and should be considered in the governance of natural resources. This is so as livelihood practices and values underpin these systems and to some degree govern these fisheries. It can therefore be concluded that where livelihoods are threatened emphasis on such practices will be made. Having noticed the latter a deeper understanding and appreciation of the cultural and social dynamics of small-scale fisher livelihoods (as shown in this case) can contribute to an enhanced understanding of the complex realities of these fishery systems, how this influences fisheries access and values and how it can promote socially and just governance approaches.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge members from the Legal Resources centre, Cape Town and Masifundise Development Trust. They collaboratively worked together on the filming and collection of one of the interviews used in this research article.

Competing interests

The author declares that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Author's contributions

S.W. is the sole author of this research article.

Ethical considerations

This research and activities undertaken did not require a formal ethical approval process to be undertaken. The author however acknowledges that ethical considerations and conduct for undertaking the research were acknowledged and approved by the Department of Environmental and Geographical Sciences and Science Faculty, University of Cape Town.

Funding information

This research was financially supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF) and the South Africa Netherlands Partnership on Alternatives in Development (SANPAD).

Data availability

There exist no restrictions on data availability.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the author.

References

Béné, C., 2006, Small-scale fisheries: Assessing their contribution to rural livelihoods in developing countries, FAO Fisheries Circular, 1008, FAO, Rome. [ Links ]

Béné, C. & Friend, R., 2011, 'Poverty in small-scale inland fisheries: Old issues, new analysis', Development Studies 11(2), 119-144. https://doi.org/10.1177/146499341001100203 [ Links ]

Berkes, F., 2010, 'Devolution of environment and resources governance: Trends and future', Environmental Conservation 37(4), 489-500. https://doi.org/10.1017/S037689291000072X [ Links ]

Berry, S., 1989, 'Social institutions and access to resources. Africa', Journal of International African Institute 59(1), 41-55. https://doi.org/10.2307/1160762 [ Links ]

Carvalho, A., Williams, S., January, M. & Sowman, M., 2009, 'Reliability of community based data monitoring in the Olifants River estuary, South Africa', Fisheries Research 96(2-3), 119-128. [ Links ]

De Villiers, G., 1987, 'Harvesting Harders Liza richardsonii in the Benguela upwelling region', South African Marine Science 5(1), 851-862. https://doi.org/10.2989/025776187784522540 [ Links ]

Du Toit, A., 2013, 'Real acts, imagined landscapes: Reflections on the discourses of land reform in South Africa after 1994', Journal of Agrarian Change 13(1), 16-22. https://doi.org/10.1111/joac.12006 [ Links ]

Fabricius, C., 2004, 'The fundamentals of community based natural resource management', in C. Fabricius & E. Koch (eds.), Rights, resources and rural development: Community-based natural resource management in Southern Africa, pp. 3-43, Earthscan, London. [ Links ]

Hutchings, K. & Lamberth, S., 2002, 'Bycatch in the gillnet and beachseine fisheries in the Western Cape, South Africa', South African Journal of Marine Science 24(1), 227-241. https://doi.org/10.2989/025776102784528619 [ Links ]

Jacobs, P. & Makaudze, E., 2012, 'Understanding rural livelihoods in the West Coast district, South Africa', Development Southern Africa 29(4), 574-587. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2012.715443 [ Links ]

Jentoft, S., 2003, 'Co-management: The way forward', in D.C. Wilson, J.R. Nielsen & P. Dengbol (eds.), The fisheries co-management experience. Accomplishment, challenges & prospects, pp. 1-14, Kluwer Academia Publishers, Dordrecht. [ Links ]

Johannes, R., 1981, Words of the Lagoon: Fishing and marine lore in the Palau District of Micronesia, University of California Press, Berkeley, CA. [ Links ]

Kalikoski, D., Jentoft, S., McConney, P. & Siar, S., 2019, 'Empowering small-scale fishers to eradicate rural poverty', Maritime Studies 18, 121-125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40152-018-0112-x [ Links ]

King, B., 2007, 'Conservation and community in the new South Africa: A case study of the Mahushe Shongwe Game Reserve', Geoforum 38(1), 207-219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2006.08.001 [ Links ]

Louw, T., 2020, 'An exploration of the post-harvest activities of the Olifants estuary small-scale fishery: Recommendations for equitable market access and beneficiation', Masters thesis, University of Cape Town, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Meinzen-Dick R. & Nkonya L., 2007, Understanding legal pluralism in water rights: Lessons from Africa and Asia, International workshop on 'African Water Laws: Plural Legislative Frameworks for Rural Water Management in Africa', 26-28 January 2005, Johannesburg, South Africa, viewed 30 March 2021, from https://www.joinforwater.ngo/sites/default/files/library_assets/W_DEC_E20_community-based_water.pdf#page=21. [ Links ]

Nelson, F., 2010, Community rights, conservation and contested land: The politics of natural resource governance in Africa, Earthscan, Washington, DC. [ Links ]

Pomeroy, R. & Andrew, N., 2011, Small-scale fisheries management: Frameworks and approaches for the developing world, Centre for Agricultural Bioscience International (CABI). [ Links ]

Purcell, S. & Pomeroy, R., 2015, 'Driving small-scale fisheries in developing countries', Frontiers in Marine Science 2, 44. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2015.00044 [ Links ]

Ribot, J. & Peluso, N., 2003, 'A theory of Access', Rural Sociology 68(2), 153-181. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1549-0831.2003.tb00133.x [ Links ]

Shackleton, S. & Shackleton, C., 2004, 'Everyday resources are valuable enough for community-based natural resource management programme support: Evidence from South Africa', in C. Fabricius & E. Koch (eds.), Rights, resources and rural development: Community-based natural resource management in Southern Africa, pp. 135-140, Earthscan, London. [ Links ]

Sowman, M., 2003, 'Co-management of the Olifants River harder fishery', in M. Hauck & M. Sowman (eds.), Waves of change, pp. 269-298, University of Cape Town Press, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Sowman, M., 2011, 'New perspectives in small-scale fisheries management. Challenges and prospects for implementation in South Africa', African Journal of Marine Science 33(2), 297-311. https://doi.org/10.2989/1814232X.2011.602875 [ Links ]

Sowman, M., 2017, 'Turning the tide: Strategies, innovation and transformative learning at the Olifants estuary', in D. Armitage, A Charles & F Berkes (eds.), Governing the coastal commons: Communities, resilience and transformation, pp. 25-42, Routledge, London. [ Links ]

Sowman, M., Beaumont J., Bergh, M., Maharaj, J. & Salo, K., 1997, 'An analysis of emerging co-management arrangements for the Olifants River harder fishery, South Africa', Proceedings, Regional Workshop on Fisheries co-management research, Mangochu, Malawi, pp. 177-203, 18-20 March 1997. [ Links ]

Tropp, J.A., 2006, Natures of colonial change: Environmental relations in the making of the Transkei, Ohio University Press, Athens, OH. [ Links ]

Urquhart, J., Acott, T. & Zhao, M., 2013, 'Introduction: Social and cultural impacts of marine fisheries', Marine Policy 37, 1-2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2012.04.007 [ Links ]

Weideman, M., 2004, 'Who shaped South Africa's land reform policy?', Politikon 31(2), 219-238. https://doi.org/10.1080/0258934042000280742 [ Links ]

Williams, S., 2013, 'Beyond rights: Developing a conceptual framework for understanding access to coastal resources at Ebenhaeser and Covie, Western Cape, South Africa', Doctoral thesis, University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

Wynberg, R. & Sowman, M., 2007, 'Environmental sustainability and land reform in South Africa: A neglected dimension', Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 50(6), 783-802. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640560701609810 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Samantha Williams

samanthawilliams@sun.ac.za

Received: 03 Mar. 2021

Accepted: 10 May 2021

Published: 18 Aug. 2021

Note: Special Collection: New Landscapes in Identity: Theological, Ethical and Other Perspectives, sub-edited by Johan Klaasen (University of the Western Cape).

1 . For those fishers who have permits issued by the management authorities their permit conditions allow the permit holder to be accompanied by crewmember or fellow fisher.