Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

HTS Theological Studies

versión On-line ISSN 2072-8050

versión impresa ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.77 no.1 Pretoria 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v77i4.6623

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Psalm 27:4 - To reflect in his temple: Communion with YHWH as the culmination of the journey of life

Philippus J. Botha

Department of Ancient and Modern Languages and Cultures, University of Pretoria, Tshwane, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Since the time of Mowinckel, the verb בקר (pi) in Psalm 27:4 was often interpreted as referring to a priest's function of examining an offering. The parallel part of the verse and other intratextual and intertextual considerations render this interpretation of the verb improbable. The context of the psalm and the cluster of Psalms 25-34, as well as parallels Psalm 27 has with Psalm 23, suggest that the verb בקר refers to reflection on the privilege of being in YHWH's presence. The enjoyment of such communion with YHWH, which includes the study of his Torah, is portrayed as the culmination of the journey of life in Psalms 25-34. The author argues that this is also hinted at in Psalm 27.

CONTRIBUTION: The contribution of this article towards the focus of HTS as "Historical Thought and Source Interpretation" centered around its use of the literary context of a psalm to question the notion of a reconstructed cultic setting as the only possible hermeneutical key to interpret Psalm 27

Keywords: Psalm 27:4; temple; house of YHWH; communion; journey of life; meditation; editing of Psalms; Psalms 25-34.

Introduction

This article attempts to interpret Psalm 27:4 within its immediate context, the broader literary and historical contexts of the cluster of Psalms 25-34, and the first book of Davidic Psalms as a whole. The verse says the following:

אַחַ֤ת׀ שָׁאַ֣לְתִּי מֵֽאֵת־יְהוָה֘ אוֹתָ֪הּ אֲבַ֫קֵּ֥שׁ שִׁבְתִּ֣י בְּבֵית־יְ֭הוָה כָּל־יְמֵ֣י חַיַּ֑י לַחֲז֥וֹת בְּנֹֽעַם־יְ֜הוָ֗ה וּלְבַקֵּ֥ר בְּהֵיכָלֽוֹ׃

27:4 One thing have I asked of YHWH, that I will seek after: that I may dwell in the house of YHWH all the days of my life, to gaze upon the kindness of YHWH and to reflect in his temple.

What is it that the psalmist wants to do in the temple of YHWH? He wants to 'dwell' in the temple so that he can 'gaze' upon the 'kindness' (or 'delightfulness' or 'pleasantness') of YHWH but then also to בִּקֵּר in his temple. Since the time of Mowinckel, this second verb was interpreted in terms of a cultic act of 'inspecting' a sacrifice. It is argued in this article that the verse and this specific verb refer to a spiritual state of communion with YHWH, not the work of a priest. The psalmist envisages such interaction with YHWH as the culmination of his journey through life.

Koehler and Baumgartner Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament, (HALOT) (1994:par. 1396) offer two meanings for the pi'el of stem I בקר: (1) a technical term within the cult, 'carry out an examination of the offering', (2) (a) to 'scrutinize' with לְ, or with ,בֵּין … ל; (b) to 'attend to', to look after with accusative; and (c) absolute to 'reflect'. For meaning 1, 2 Kings 16:15 and Psalm 27:4 are listed in HALOT, although sense 2(c) is also offered as an alternative. Koehler and Baumgartner (1994) offer meaning 1 with a question mark, perhaps indicating that there is doubt about this meaning. Recently, Sommer (2021:359) has vowed for meaning 2(b) in this verse, translating the hemistich with 'and to serve in his palace' (Sommer 2021:355). His view is that the worshipper in Psalm 27:4 wants some responsibility that will keep him in the temple 'on a long-term basis' (Sommer 2021:359).

The idea that the form in Psalm 27:4 refers to the inspection of an offering is, however, problematic. Mowinckel reconstructed a presumed cultic procedure in Israel during which a priest would inspect the entrails of a sacrificial animal to gain information about the will of God or to determine the guilt or innocence of an accused worshipper. Mowinckel (2014a:150) states that 'to view his beauty' in Psalm 27:4 means that the supplicant wanted to be able to appear before YHWH in his temple. There, he wanted to experience YHWH's grace and to 'biqqēr in his palace', which, he says, is 'a technical cultic expression', because the parallel phrase 'to view YHWH's beauty' is 'likely' such a technical cultic expression (Mowinckel 2014a:150). From 2 Kings 16:15 and Psalm 27:6, he infers that biqqēr describes 'an act that takes place in conjunction with the sacrifice'. Since the root בקר means 'to divide', the pi'el must mean 'to examine closely' and, in a cultic sense, must denote the examination of the sacrifice to give an oracle (Mowinckel 2014a:150).1

It is evident that this exposition of Psalm 27:4 gave rise to meaning (1) in HALOT (there is a reference to Mowinckel's Psalmenstudien 1:146 at this entry). This interpretation should be regarded as questionable as the verb does not have an object in Psalm 27:4. The intended meaning is probably 2(c), to 'reflect' as in Proverbs 20:25. The 'sacrifices' which Mowinckel uses to justify his interpretation are only mentioned two verses later (Ps 27:6). These are described as 'sacrifices of jubilation' described in parallel to 'sing' and 'make music'. The sacrifices are, thus, not real. In Psalm 51:21, the זבחי צדק ('sacrifices of righteousness') are not real sacrifices but describe an ethical lifestyle because they are compared to 'a broken spirit and a crushed heart' in Psalm 51:19 (Janowski 2014:193-194). In a similar way, the זבחי תרועה of Psalm 27:6 should be understood as 'sacrifices of joyous thanksgiving' for salvation, not as sacrifices accompanied by joyful shouting.

As Janowski (2014:199) remarks concerning the זבח תודה in the Psalms, the זבחי תרועה in Psalm 27:6 reflect a theology of gratefulness which defines the relationship between God and humanity in a new way, transcending the cult but without abandoning its context. The temple became the (symbolic) centre for a personal, direct encounter with YHWH (thus, without the priest's mediation). The context of Psalm 27:4 is one of thanksgiving by a worshipper, not inquiry by a priest.

Of the biblical texts cited by Mowinckel, only one speaks about divination as a cultic act, namely, 2 Kings 16:15. In that verse, the same form of the verb בקר is used to describe King Ahaz's instruction to Uriah, the priest. He wanted Uriah to offer sacrifices on the great altar, adding that 'the bronze altar shall be for me to inquire (by)'. It is indeed possible that Ahaz wanted to use it for divination. However, it must be remembered that this king had Uriah build a new altar on the pattern of one he saw in Damascus and that he also had the bronze altar moved to a new location for his private purpose. This purpose should probably be understood as improper like his other cultic violations (cf. 2 Ki 16:2-15). To construct a 'normal' Israelite custom from this one verse and find a reference to it in Psalm 27:4 is going too far. Yet Mowinckel's interpretation is still widely accepted.2 It is proposed here that a textual and contextual analysis of the verse line and Psalm 27 in its literary context will point to a different, more probable, interpretation of what בקר means here.

Psalm 27:4 in the context of Psalm 27

The crux interpretum of Psalm 27 is the question of its unity. It seems to have two distinct parts, with the second part not following logically after the first. Psalm 27:1-6 is usually described as a confession of trust of an individual, possibly a King, whilst 27:7-14 is defined as the supplication of an innocent but falsely accused follower of YHWH (Hossfeld & Zenger 1993:171). The combination and the sequence of the two parts are confusing because a declaration of wholehearted trust in YHWH's protection in 27:1-6 is abruptly followed by a desperate call for help in 27:7.

Much work has been conducted to try to explain the unity of the psalm. Gunkel simply treats the two parts as two separate psalms: a psalm of trust (27:1-6) and a 'very different' lament (27:7-14) (Gunkel 1986 [1926]:113, 116). Mowinckel (2014b:808) considers it one of the 'individual sin-offering psalms', an individual lament related to some rite of purification and healing performed for sick and unclean persons in the temple when bringing a sin offering. In support of Mowinckel, Birkeland (1932:216-221) considers the complete psalm to be a lament with an extended declaration of trust at the beginning (cf. also Van Zyl 1971:233-251). Because the crisis is not so big and still lies in the future, trust is introduced at the beginning as motivation for God's acceptance of the supplication (Birkeland 1932:220). Auffret (1968:112) says that it would be more logical to read the psalm from the last section to the first, but he insists that it is theologically meaningful to move from trust in God to supplication to the one who is the source of that trust. Konkel (2012:322-336) interprets the psalm as a paradigmatic text intended to teach a person how to pray: in the first part, he or she has to cite a text from a royal prayer of trust; this enables him or her to enter into the presence of God and to express his or her doubt and hope in the words of the second part. Brueggemann and Bellinger (2014:loc. 3892) remark that the psalm's poetry resists the attempt to restrict the psalm to any single setting. According to Barbiero (1999:415), a broader perspective, which considers the cluster's context in Psalms 25-34, explains the unusual sequence of lament following trust in Psalm 27. This sequence creates a pattern that slots in logically with the succeeding psalms. The Table 1 from Barbiero (1999:415) explains this:

This exposition draws the attention to the chiastic pattern created by the sequence of moods in the adjacent psalms, namely, trust/praise - lament : : lament - praise/trust in Psalms 27-28 and, at the least, suggests that a broader contextual perspective can provide a solution to interpretational problems found within one psalm. It also serves to indicate that no single cultic context, such as that of a person seeking asylum or an innocently accused suppliant seeking removal of suspicion from him or her, can explain the mixture of forms in the psalm. The range of divergent metaphors used in the composition probably instead point to a creative literary mix of divergent symbols.

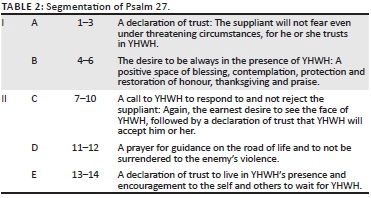

To present the context of Psalm 27 itself for interpreting verse 4, the following segmentation is offered:

I

A

1a

לְדָוִ֙ד׀

Of David.

b

יְהוָ֤ה׀ אוֹרִ֣י וְ֭יִשְׁעִי מִמִּ֣י אִירָ֑א

Yahweh is my light and my salvation; whom shall I fear?

c

׃יְהוָ֥ה מָֽעוֹז־חַ֜יַּ֗י מִמִּ֥י אֶפְחָֽד

Yahweh is the stronghold of my life; of whom shall I be afraid?

2a

בִּקְרֹ֤ב עָלַ֙י׀ מְרֵעִים֘ לֶאֱכֹ֪ל אֶת־בְּשָׂ֫רִ֥י

When they encroach upon me, evildoers, to eat up my flesh,

b

צָרַ֣י וְאֹיְבַ֣י לִ֑י

my adversaries and enemies,

c

׃הֵ֖מָּה כָשְׁל֣וּ וְנָפָֽלוּ

It is they who stumble and fall.

3a

אִם־תַּחֲנֶ֬ה עָלַ֙י׀ מַחֲנֶה֘ לֹֽא־יִירָ֪א לִ֫בִּ֥י

Though an army encamp against me, my heart shall not fear;

b

אִם־תָּק֣וּם עָ֭לַי מִלְחָמָ֑ה

though war arise against me,

c

בְּ֜זֹ֗את אֲנִ֣י בוֹטֵֽחַ׃

on this I trust.

B

4a

אַחַ֤ת׀ שָׁאַ֣לְתִּי מֵֽאֵת־יְהוָה֘ אוֹתָ֪הּ אֲבַ֫קֵּ֥שׁ

One thing I have asked from Yahweh, this I will seek out:

b

שִׁבְתִּ֣י בְּבֵית־יְ֭הוָה כָּל־יְמֵ֣י חַיַּ֑י

that I may dwell in the house of Yahweh all the days of my life,

c

לַחֲז֥וֹת בְּנֹֽעַם־יְ֜הוָ֗ה וּלְבַקֵּ֥ר בְּהֵיכָלֽוֹ׃

to gaze upon the kindness of Yahweh and to reflect in his temple.

5a

כִּ֤י יִצְפְּנֵ֙נִי׀ בְּסֻכֹּה֘ בְּי֪וֹם רָ֫עָ֥ה

For he hides me in his hut on the day of trouble;

b

יַ֭סְתִּרֵנִי בְּסֵ֣תֶר אָהֳל֑וֹ

he conceals me in the shelter of his tent,

c

בְּ֜צ֗וּר יְרוֹמְמֵֽנִי׃

on a rock he lifts me up high.

6a

וְעַתָּ֙ה יָר֪וּם רֹאשִׁ֡י עַ֤ל אֹֽיְבַ֬י סְֽבִיבוֹתַ֗י

And now my head shall be high above my enemies around me,

b

וְאֶזְבְּחָ֣ה בְ֭אָהֳלוֹ זִבְחֵ֣י תְרוּעָ֑ה

and I will offer in his tent sacrifices of shouts of joy;

c

אָשִׁ֥ירָה וַ֜אֲזַמְּרָ֗ה לַיהוָֽה׃

I will sing and make music to Yahweh.

II

C

7a

שְׁמַע־יְהוָ֖ה קוֹלִ֥י אֶקְרָ֗א

Hear, Yahweh, my voice when I cry aloud;

b

וְחָנֵּ֥נִי וַעֲנֵֽנִי׃

be gracious to me and answer me!

8a

לְךָ֤׀ אָמַ֣ר לִ֭בִּי בַּקְּשׁ֣וּ פָנָ֑י

Concerning you, my heart has said: 'Seek my face'.

b

אֶת־פָּנֶ֖יךָ יְהוָ֣ה אֲבַקֵּֽשׁ׃

Your face, Yahweh, I seek.

9a

אַל־תַּסְתֵּ֬ר פָּנֶ֙יךָ׀ מִמֶּנִּי֘ אַֽל־תַּט־בְּאַ֗ף עַ֫בְדֶּ֥ךָ

Do not hide your face from me; do not turn your servant away in anger,

b

עֶזְרָתִ֥י הָיִ֑יתָ

you who have been my help!

c

אַֽל־תִּטְּשֵׁ֥נִי וְאַל־תַּֽ֜עַזְבֵ֗נִי אֱלֹהֵ֥י יִשְׁעִֽי׃

Do not cast me off and do not forsake me, O God of my help!

10a

כִּי־אָבִ֣י וְאִמִּ֣י עֲזָב֑וּנִי

Even if my father and my mother abandon me,

b

וַֽיהוָ֣ה יַֽאַסְפֵֽנִי׃

Yahweh will accept me.

D

11a

ה֤וֹרֵ֥נִי יְהוָ֗ה דַּ֫רְכֶּ֥ךָ

Teach me, Yahweh, your way,

b

וּ֭נְחֵנִי בְּאֹ֣רַח מִישׁ֑וֹר

and lead me on a level path

c

לְ֜מַ֗עַן שׁוֹרְרָֽי׃

because of my opponents.

12a

אַֽל־תִּ֭תְּנֵנִי בְּנֶ֣פֶשׁ צָרָ֑י

Do not give me up to the desire of my opponents;

b

כִּ֥י קָֽמוּ־בִ֥י עֵֽדֵי־שֶׁ֗֜קֶר וִיפֵ֥חַ חָמָֽס׃

for false witnesses arise against me, and they breathe out violence.

E

13a

לׅׄוּלֵׅ֗ׄאׅׄ הֶ֭אֱמַנְתִּי לִרְא֥וֹת בְּֽטוּב־יְהוָ֗ה

If I did not believe that I will look upon the goodness of Yahweh

b

בְּאֶ֣רֶץ חַיִּֽים׃

in the land of the living!

14a

קַוֵּ֗ה אֶל־יְה֫וָ֥ה

Wait for Yahweh!

b

חֲ֭זַק וְיַאֲמֵ֣ץ לִבֶּ֑ךָ

Be strong and let your heart be strong!

c

וְ֜קַוֵּ֗ה אֶל־יְהוָֽה׃

Wait for Yahweh!

The psalm can be schematically summarised as follows:

Psalm 27:4 is about the desire of the psalmist to see the face of YHWH, and thus to be accorded an audience, to be in his presence; verse 5 is about the protection YHWH provides to the suppliant in the temple; verse 6 is about the praise and thanksgiving the speaker wants to present for the protection provided by YHWH. There is no indication of a need or desire for inspecting a sacrificial animal. When a worshipper is in YHWH's presence, there can hardly be the need for him to communicate with that person through divination. The final part of verse 4 must, consequently, also be interpreted in terms of the privilege of being in the temple in the presence of YHWH.

There is indeed a mood change at the beginning of verse 7, but the second stanza confirms the trust and the desire for communion with YHWH expressed by the psalmist in the first half. The two stanzas of the psalm share three significant motifs: (1) in both sections, there is mention of the threats of enemies (vv. 2-3 and 11-12), (2) there are declarations of trust in YHWH in both sections (vv. 1, 3 and 10, 13) and (3) there are also expressions of a desire to be in the presence of YHWH with all the privileges it brings in both (vv. 4-6 and 8, 13).

The repetition of several lexemes occurring in both sections suggests that the similarity between the two is no accident: the presence of בקשׁ in verse 4 and its repetition twice in verse 8 strengthen the connection between the 'searching' for the presence of YHWH. The use of לב in verse 3 and its being repeated in verse 14 emphasise the confidence of the suppliant. The use of סתר in verse 5 and its repetition in verse 9 emphasise the protection available in the benevolent presence of YHWH and the need to have access to him. The occurrence of צר in verse 2 and its repetition in verse 12 draw attention to the fact that the opponents constitute a threat in both halves of the psalm. Finally, the use of קום in verse 3 and its repetition in verse 12 underscore the motif of the enemies rising against the suppliant in a threatening way.

Different expressions use words from the same semantic field that establish links between the two parts: to 'gaze upon the kindness of YHWH and to reflect in his temple' in verse 4 is similar in meaning to 'look upon the goodness of YHWH in the land of the living' in verse 13. The verb בטח is used in verse 3 to express the trust of the suppliant in YHWH, but the same idea is expressed with אמן (hif'il) in verse 13.

The result of noting the repetition of motifs in the two main sections of Psalm 27 is that an additional context is created for understanding verse 4, especially the 'searching' of YHWH in verse 8 and of perceiving his 'goodness' in verse 13. What is thus meant by the author (or editors) with the pronouncement in verse 4?

4a

אַחַ֤ת׀ שָׁאַ֣לְתִּי מֵֽאֵת־יְהוָה֘ אוֹתָ֪הּ אֲבַ֫קֵּ֥שׁ

4 One thing I have asked from Yahweh, this I will seek out

b

שִׁבְתִּ֣י בְּבֵית־יְ֭הוָה כָּל־יְמֵ֣י חַיַּ֑י

that I may dwell in the house of Yahweh all the days of my life

c

לַחֲז֥וֹת בְּנֹֽעַם־יְ֜הוָ֗ה וּלְבַקֵּ֥ר בְּהֵיכָלֽוֹ׃

to gaze upon the kindness of Yahweh and to reflect in his temple

The author says that he has one dominant desire: to be in the presence of YHWH in the temple as long as he lives so that he can see the friendliness or kindness of YHWH and to 'reflect' in his temple.

Gunkel (1986 [1926]:113) thinks that the temple itself is the implied object of לבקר: He regards verse 4c as a distichous verse line and translates it as follows: 'dass ich Jahves Freundlichkeit schaue | und seinen Tempel betrachte' ('that I would be able to see YHWH's friendliness and look at his temple'). He explains it as the expression of a desire of someone living far away to be considered worthy to perceive YHWH's friendly kindness in the temple and look at the holy temple. Gunkel, thus, understands the preposition בְּ attached to 'temple' as an indication of the object of perception rather than the place in which the perceiving occurs. He refers to the similar Egyptian expressions of seeing the 'beauty' of God, which in those contexts mean to see the 'image' of God. However, he says that in the case of Psalm 27, the psalmist thinks of seeing the holy places, symbols and acts that will serve for him as a powerful, touching experience of the friendliness of YHWH (Gunkel 1986 [1926]:113).

Concerning the final part of the verse, Gunkel (1986 [1926]:113) says that one can visualise how the psalmist imagined he would stroll through the sanctuary, looking at everything with love and joy. Included in his desire is also the need to be saved from his distress because this is the reason for the wish in verse 5. Therefore, the image that the psalmist used is a combination of two images: that of the sanctuary as a place of pilgrimage and that of it as a place of asylum for the persecuted (Gunkel 1986 [1926]:113). Gunkel (1986 [1926]:115) goes on to say that, to see YHWH's 'kindness' (נעם) is a poetic variation of seeing YHWH as it is expressed in Psalm 42:3 (cf. Psalms 11:7; 17:15; 63:3), a description of visiting God in the temple. Gunkel explains the combination of בקר with בְּ as 'perceiving with inner participation, with delight' (Gunkel 1986 [1926]:115). Accordingly, he denies explicitly that it can be represented with 'nachsinnen' ('reflect, ponder, meditate'), because this does not fit the parallel לחזות; or with performing a cultic act, as the psalmist desires proximity to God and inner elevation, not a cultic duty; neither with conducting an 'Opferschau' (inspection of the sacrifice, as Mowinckel thought), because this also does not fit into the context (Gunkel 1986 [1926]:115).

Gunkel (1986 [1926]:115), thus, interpreted 'seeing' the נעם of YHWH as referring to being granted a divine audience, and the parallel part of 'ולבקר בהיכלו' as looking with joy at the temple complex itself. I think that Gunkel is mistaken regarding the second part. The two sections of verse 4c indeed form a grammatical parallel, but they do not have to be semantic parallels in all respects:

לַחֲז֥וֹת בְּנֹֽעַם־יְ֜הוָ֗ה

to gaze upon the friendliness of Yahweh

וּלְבַקֵּ֥ר בְּהֵיכָלֽוֹ׃

and to reflect in his temple.

The two phrases form a synthetic parallel rather than a synonymous parallel. The combination of חזה plus ב occurs only six times in the Hebrew Bible. It refers to perceiving the great work of God (Job 36:25), gazing upon the friendliness of YHWH (Ps 27:4), the audience looking upon the Shulamite girl (Song 7:1 x 2), the counsellors of the Babylonians gazing at the stars (Is 47:13) and the nations desiring to gaze upon (the destruction of) Zion (Mi 4:11). Whilst 'gaze upon' is encountered six times in the Hebrew Bible, the combination of בקר and בְּ occurs only in Psalm 27:4. For 'scrutinise', the preposition לְ is used with בקר (as in Lv 13:36); for 'differentiate', the preposition בֵּין is used (as in Lv 27:33). In the meaning 'search out' (parallel to דרשׁ, as in Ezk 34:11), the accusative is used. Therefore, the verb cannot be a complete parallel of חזה in Psalm 27:4.

In the second main section of Psalm 27, in 27:13, the poet speaks in a similar way of believing that his seeking the face of YHWH will lead to 'looking upon the goodness of YHWH in the land of the living'. As was argued above, the phrases לחזות־בנעם יהוה in verse 4 and לראות בטוב־יהוה in verse 13 are parallel formulations describing the enjoyment of the privileges associated with being in the presence of YHWH. The expression 'to see good' usually describes enjoying prosperity (cf. Job 7:7; Ps 4:7, 34:13; Ec 3:13). In the cluster of psalms running from 25 to 34, with its focus on the temple and the presence of YHWH, such blessings are often called to mind. To focus on this context will be the next step in the investigation: considering the context of the cluster of which Psalm 27 forms a part.

Psalm 27:4 in the context of the clusters 25-34

The immediate literary context around Psalm 27 should be considered as the second hermeneutic milieu for the interpretation of Psalm 27:4. The reason for this is that Psalms 25-34 constitute a palindromic cluster arranged and edited to form a unit (see Barbiero 1999:325-541; Botha & Weber 2019:19-50; Hossfeld & Zenger 1993:13, 1994:375-388). In this cluster, Psalm 25 corresponds to 34, 26 corresponds to 32 and 33, 27 corresponds to 31 and 28 corresponds to 30. Psalm 29 forms the hymnic centrepiece of the arrangement. The similar endings of Psalms 27 and 31, with the similar exhortations to be strong and to 'wait' for YHWH in 27:14 (קוה, cf. also 25:3, 5, 21) and 31:25 (יחל), the account of the urgent call to YHWH in 27:7 and the report of YHWH's positive response to that call in 31:23, and especially the similarity between the descriptions of YHWH's acts of saving in the temple area where he conceals (צפן) the suppliant and protects him in his tent or in his presence in 27:5 and 31:20-21, respectively, can be cited as indications of the work of the editors who established connections between Psalms 27 and 31 (Hossfeld & Zenger 1994:380-381). The editors also added a frame to the cluster through the (composition and) insertion of Psalms 25 and 34. By doing this, they transformed a group of individual prayers into prayers of the poor, representatives of the pitiful people of YHWH who live in distress and are dependent on YHWH's help (Hossfeld & Zenger 1994:386).

In terms of its location within the cluster, Psalm 27:4 should perhaps be interpreted first in the context of the preceding two psalms, namely, Psalms 25 and 26, as they are more important in a linear reading, but then also in its relation to Psalm 31, its counterpart in the cluster and finally also Psalm 34, the concluding psalm of the cluster.

Psalm 25 is a prayer for forgiveness of youthful sins and a request for help against violent enemies who want to hurt and shame the suppliant. The psalmist asks YHWH to be gracious to him, forgive his past sins and instruct him about the road of life because he (YHWH) is good and those who worship him will enjoy his blessings of goodness. Included amongst those blessings is the expectation that the person who fears YHWH will be taught about the way of life (25:12), will abide (לין) in well-being (טוב) (25:13), and his descendants will take possession of the land (ארץ) (25:13).

These remarks are relevant for understanding Psalm 27:4 and 13 because those verses also speak of the desire (27:4) and the trust of the suppliant (27:13) to be able to reside (ישׁב) in YHWH's presence and enjoy his kindness and his goodness (חזה בנעם in 27:4 and ראה בטוב in 27:13).

Instead of the land of Israel, Psalm 27:13 mentions looking upon the goodness of YHWH in 'the land of the living', but as Barbiero (1999:370-1) explains, 'the land of the living' is not only about staying alive but also refers to the land of Israel here. The author or editor of Psalms 25-27 expects to reach YHWH's presence in the temple. He is on his way there, busy with a pilgrimage, and road imagery forms a strong connection between Psalms 25-27. In Psalm 26, the verbs הלך and עמד are used to refer to the road of life, with the psalmist again being on his way to the temple (26:1, 3, 11-12) where he will reach the centre of his life at the altar (which he wants to circumnavigate, סבב, in 26:6), and thus be in YHWH's presence. In Psalms 25 and 27, the nouns דרך (25:4, 8, 12; 27:11) and ארח (25:4, 10; 27:11) are used to refer to the journey to God's presence, which is also the journey of life and the journey of the Torah (Barbiero 1999:371).

In Psalm 25, the metaphoric sense of the 'way' as the Torah is emphasised. It is described, amongst other things, as YHWH's 'truth' (אמת 25:5), 'what is right' (משׁפט 25:9), 'steadfast love and faithfulness' (חסד ואמת 25:10) and YHWH's 'covenant' (ברית 25:14). In Psalm 26, the pilgrimage to the temple is more important than the journey of life, and this is also true of Psalm 27. Right in the middle of Psalm 26, the psalmist expresses the desire to move around the altar (which represents the temple's centre, YHWH's presence and the culmination of life).

Although the journey of life dominates in Psalm 25, the motif of the temple is also present in it, being represented with the verb חסה ('to take refuge', 25:20), an action which is in turn related to the response of YHWH described with the verb צפן ('to hide' the psalmist) in Psalm 27:5.

The pilgrimage mentioned in Psalms 26 and 27 can also be understood metaphorically as the journey of life: YHWH should 'show' the psalmist his way (25:4, 8, 12; 27:11). Therefore, it is not only the road to Zion that is at stake but also the 'road of YHWH', thus the road of life or the road of Torah (Barbiero 1999:371). The temple serves as the symbol of YHWH's presence (cf. the use of פנים and פנה in 25:16; 27:8-9). Similarly, the temple is equated with the land (cf. 25:13; 27:13, Barbiero 1999:371).

It was argued above that the construction חזה בנעם־יהוה in Psalm 27:4 is parallel to the construction ראה בטוב־יהוה in Psalm 27:13. The many instances of the stem טוב in this cluster of psalms throw light on the meaning of the נעם־יהוה, the 'kindness' or 'friendliness' of YHWH in Psalm 27:4. In Psalm 25:7, the suppliant asks YHWH to forget the sins of his youth and rather remember him according to his steadfast love, for the sake of his 'goodness' (טוּב). In 25:8, he states that YHWH is 'good and upright' and that is why he instructs sinners in the way. In 25:12, there is the promise that the person who fears YHWH will receive instruction in the way that he should choose, followed in 25:13 by the promise that his 'soul will abide in well-being (טוֹב)', and that 'his offspring will inherit the land'.

Instruction about the way of life, enjoying the privileges of being in YHWH's presence and the land promise are closely related in Psalm 25. In Psalm 27:11, there is also a prayer that YHWH would teach the suppliant his way and lead him on a level path because of his enemies, followed in 27:13 with the confession that the suppliant believes he will look upon the goodness of YHWH in the land of the living. To receive instruction in the way of life is part and parcel of the privileges enjoyed by those who fear YHWH and desire to be in his presence.

Concerning the theme of 'goodness' in Psalms 31 and 34, there is in 31:19 an exclamation about the abundant goodness (טוּב) of YHWH which he has stored up for those who fear him and worked for those who take refuge in him 'before the eyes of humanity'. In Psalm 27, the 'friendliness' of YHWH is also closely connected to his protection of the psalmist (Ps 27:4-5). Finally, in Psalm 34, the stem טוֹב is repeated several times. In 34:9, the audience is invited to 'taste and see that YHWH is good', with the added assurance that the man who takes refuge in him is blessed. Psalm 34:11 then states that young lions suffer want and hunger, but those who seek YHWH lack no good thing. This echoes the idea of Psalm 27 that those who seek the presence of YHWH will see his kindness and goodness (cf. 27:4, 8, 13). The invitation to 'see good' (similar to Ps 27:13) is subsequently repeated in Psalm 34:13: 'What man is there who desires life and loves many days, that he may see good?' From the parallels in the cluster in which 'seeing the goodness of YHWH' is combined with seeking refuge in the temple and with being taught YHWH's way, it seems logical to conclude that the psalmist who composed Psalm 27:4 expressed in this verse the desire to abide symbolically in the temple, in YHWH's presence, and to enjoy the blessings this brings with it (see McCann [2005] on the importance of these aspects in Book I of the Psalms). Included in those blessings would be the privilege of being taught the way of YHWH, the way one should choose (25:12), thus the Torah (cf. ירה in 27:11).

To summarise this section, it can be stated that in Psalms 25-27, the journey towards the presence of YHWH, which takes place on the 'road of life' and which is a journey under his instruction, therefore, also called the 'road of YHWH', forms an important theme. This metaphor features in 25:4, 5, 8, 9, 10, 12; 27:11; and 32:8. The road of YHWH is the road of his Torah. This fact is also hinted at when the verb ירה is used (25:8, 12; 27:11). The opponents of the psalmist would like to entrap the psalmist on this road of life (25:15; 26:9-10), but through his trust in YHWH (25:2; 26:1; 27:3), through seeking refuge with YHWH (25:20; 27:5) and through his desire to be in YHWH's presence (26:8; 27:4, 8), the suppliant will arrive at his destination in the presence of YHWH (25:13; 27:13). There he will enjoy protection (27:5) and the privilege to reside, enjoying the well-being it brings (25:13; 27:13). By following YHWH's instructions (25:12; 26:1-3, 11), he will avoid stumbling on the road of life (27:2; 11) or ending up residing in the company of the wicked opponents (26:4-5). He will overcome their attacks with YHWH's help (25:5, 19-20; 27:2-3) and arrive safely in YHWH's presence to reside there and offer thanksgiving (26:12; 27:5-6). YHWH's road is lonely, a road of isolation (25:16; 26:4, 5), but to be in YHWH's company eventually makes it worthwhile because he compensates for this loneliness abundantly (25:14; 27:10). According to Psalm 25:14, this includes YHWH's discussing his secrets and making known to them his covenant, thus teaching them his Torah (this idea is also suggested in Pr 3:32).

Because of the focus on this motif in these three psalms, it seems plausible to understand the verb לבקר in 27:4, 'to reflect in his temple', as a reference to meditation on the Torah of YHWH. Accepting YHWH's instruction as the guide on the road of life involves meditation on it (Ps 1:2, 119:27), an act that is accompanied by enjoyment (see below). In the other two 'significant' psalms (significant for understanding Ps 27) in the cluster, Psalms 31 and 34, the picture is very similar. The theme of refuge with YHWH resonates in Psalm 31:2-4 and 20-21, with YHWH also being depicted as the one who 'leads' (נחה) and 'guides' (נהל) the suppliant (31:4). The trust of the suppliant in YHWH as saviour is also emphasised (31:6, 15-16), as is the traveller's loneliness (31:12, 13). The journey itself is hinted at in 31:5 (the 'net' from which the suppliant escaped is mentioned, cf. 25:15) and in 31:9 (YHWH having set his feet in a 'broad place', which means he has arrived in safety in the temple). Psalm 31:20 also mentions the abundant goodness (טוב) YHWH has stored up and worked for those who take refuge in him. Psalm 34, in turn, focuses more on thanksgiving for YHWH's help, but the audience is invited to experience YHWH's goodness (טוב), again by seeking refuge in him (34:9, 23). Those who seek YHWH (cf. 27:8), we are assured, have no lack of anything good (טוב, 34:11). In this psalm, the psalmist himself takes on the role of teacher of the Torah, telling his audience that those who 'love days to see good' (34:13) should keep themselves from speaking deceit (34:14), should turn away from evil and do good and should seek peace and pursue it (34:15).

Psalm 27:4 in relation to Psalm 23 (and Psalm 16)

Psalm 27 does have cultic echoes, such as the reference to 'offering sacrifices of thanksgiving' in 27:6 and the reference to 'false witnesses' in 27:12. The descriptions of the temple such as 'the house of YHWH' and 'his temple' in 27:4 and 'his shelter', 'his tent' and 'a rock' in 27:5 in Psalm 27 are focused on the protection associated with being in the presence of YHWH and on the privileges associated with his presence rather than on liturgical procedures. This dual focus is also characteristic of Psalm 23, a psalm with which it shares many similarities. Barbiero (1999:373) lists numerous stems and phrases that the two psalms have in common and refers to Duhm who thinks that the same author could have composed them. The most conspicuous similarity between Psalm 23 and Psalm 27 is, of course, the one that involves Psalm 23:6 and Psalm 27:4:

23:6

אך טוב וחסד ירדפוני כל־ימי חיי ושׁבתי בבית־יהוה לארך ימים

27:4

אחת שׁאלתי מאת־יהוה אותה אבקשׁ שׁבתי בבית־יהוה כל־ימי חיי לחזות בנעם־יהוה ולבקר בהיכלו

The bold and italic words in the quotations above are the same. There are also differences: (1) the sequence of the two similar phrases כל־ימי חיי and שׁבתי בבית־יהוה are inverted in 27:4; (2) in 23:6, they form part of two different cola, but in Psalm 27:4 they constitute one colon; and (3) שׁבתי was vocalised differently in the two psalms by the Masoretes: In Psalm 23:6, we have 'I will return (שׁוב)' and in Psalm 27:4, 'my dwelling (ישׁב)'. Because the phrases are so similar, exegetes (e.g. Kraus 1978:367) have thought that all the repeated words in Psalm 27:4 should be considered a gloss copied from Psalm 23:6. But, given all the other similarities between the two psalms, it seems more probable that we have a case of intentional cross-reference. Barbiero (1999:374) speaks of 'unmistaken paronomasia' between שַׁבְתִּי and שִׁבְתִּי. There is also another instance of paronomasia between the two psalms, namely, the references to the enemies that surround the suppliant: צררי in 23:5 sounds remarkably similar to שׁוררי in 27:11 (Barbiero 1999:374).

In addition to these similarities, the two psalms have a conspicuously similar beginning. The confession 'YHWH is my shepherd; I shall not want' in 23:1 closely resembles 'YHWH is my light and my salvation; whom shall I fear?' in 27:1. Between רעי ('my shepherd') and ארי ('my light'), there are also connections of alliteration and assonance. In both psalms, a conditional sentence is followed by a similar negative statement about lack of fear (ירא) on the part of the psalmist in 23:4 and 27:3 (Barbiero 1999:374): 'Even if I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil (לא אירא רע) … ' (23:4), and 'Though an army encamp against me, my heart shall not fear (לא־יירא); though war arise against me, yet I will trust' (27:3). Another remarkable similarity noted by Barbiero (1999:374) is the reference to YHWH's guidance on the way of life:

23:3

נפשׁי ישׁובב ינחני במעגלי־צדקלמען שׁמו׃

27:11

הורני יהוה דרכך ונחני בארח מישׁור למען שׁוררי׃

The 'tracks of righteousness' of 23:3 are equivalent to the 'level path' of 27:11. Both expressions refer to righteous conduct. When YHWH 'guides' one in the 'tracks of righteousness' or on a 'level path', he serves as a guide on the road of life (thus, YHWH's way), helping the psalmist to walk in integrity (cf. Ps 26:11-12 where 'to walk in integrity' is used as the equivalent of having one's foot 'standing on level ground'). In both psalms, the psalmist is busy with a pilgrimage to the temple (23:5, 6; 27:4, 13), which is simultaneously the way of life (cf. חיים in 23:6; 27:1, 4, 13) (Barbiero 1999:375). YHWH's guidance on the road of life, and thus on the road of pilgrimage, contributes to the glory of his name (23:3), and it helps to protect the psalmist against his enemies (27:11). When the psalmist arrives at his destination in the presence of YHWH, he will be able to participate in the abundance of YHWH (טוֹב in 23:6; נעם and טוּב in 27:4, 11), whilst his honour (ראשׁ in 23:5; 27:6) will be restored and this will contribute to the disgrace of his enemies around him (נגד צרר in 23:5; סביב איב in 27:6).

As Barbiero (1999:375) rightly remarks, the authors of these psalms considered themselves to be members of the group of 'poor people'. This is expressed in Psalm 25:16 as being 'lonely and afflicted' and in Psalm 27:10 as being 'forsaken' by one's father and mother. Their only riches were YHWH (Barbiero 1999:375). To see his face, to be in his presence, is what satisfied them (16:11; 23:5; 27:4). Their attachment to YHWH, which would have no end, filled them with joy and happiness (נעם in 27:4; שׂבע שׂמחות and נעמות נצח in 16:11) (cf. Barbiero 1999:375).

It is notable that in many of the psalms composed by the editors, or which they extensively edited, the joy experienced through the interaction with YHWH is also closely associated with YHWH's involvement in guiding on the road of life. Psalm 1:2 speaks about the 'delight' (חפץ) of the person who is on the road of life because he studies the Torah day and night; the author of Psalm 16 speaks about the 'pleasant places' (נעמים) in which the measuring lines have fallen for him, and in the next verse makes mention of YHWH who 'counsels' (יעץ, 16:6, 7) him continually, whilst in Psalm 16:11 he again mentions YHWH's 'teaching' the 'path of life' and associates this with the 'pleasures' (נעים) in his right hand. In Psalm 25:12-13, the instruction about the way the one who fears YHWH must choose is also mentioned in association with the 'goodness' that person will enjoy. The adjective נעים ('pleasant, delightful, lovely') found in Psalm 16:6 and 11 and the noun נעם which derives from the same root and which is used in Psalm 27:4 ('kindness, friendliness') establish a connection between them, and so do the nouns טוֹב and טוּב ('goodness') encountered in Psalms 16:2, 23:6, 25:13 and 27:13. In Psalms 16, 23 and 27, there are strong suggestions that the 'goodness' and joy the suppliant will experience in the presence of YHWH will be permanent. In other words, it is connected to the expectation of life everlasting. Suggestions of this are found in Psalms 16:10, 23:4 and 27:13 (Barbiero 1999:375).

When Psalm 27 is read as part of the literary context surrounding it and compared to other psalms in Book I with similar features, the various metaphors combined in its composition do not clash. It is only when the metaphors are linked directly to different cultic situations that one encounters clashes. But if the metaphors are understood as symbols of the psalmist's experiences, they form a harmonious whole in which the psalmist describes his present struggles and future hopes with the help of fixed images. Part of his expectation for the future is to arrive at a situation where he will be permanently in the presence of YHWH. On the road to YHWH's presence, on the road of life, he travels under the guidance of YHWH. Seeing YHWH's friendliness and pondering his guidance will be the highest form of enjoyment the psalmist can hope to achieve. It is also the hope that keeps the psalmist moving forward on the road of life (27:13) and the inspiration for the appeal to the self and others to wait patiently for YHWH at the end of this and other psalms in the cluster (cf. 25:3, 5, 21; 27:14; 31:25).

Conclusion

When one considers the variety of metaphors and the mix of genres in Psalm 27, it seems difficult to explain the psalm in its present form as a liturgical text for a particular cultic rite. Is the suppliant a king threatened by enemies (27:3), an asylum seeker (27:5), a pilgrim longing for the temple (27:4) or an innocently accused individual (27:12)? He or she is probably all of these: the various metaphors can only be explained satisfactorily as different expressions of the one comprehensive desire of the psalmist to be freed from the attacks of opponents, to have a safe journey through life and to be permanently in the presence of YHWH (27:4, 8-11, 13). In the context of the psalm as a whole, of the cluster of which it forms a part, and in comparison with Psalms 16 and 23 with their similar features, the various metaphors in Psalm 27 can be assimilated under the auspices of the journey of life, undertaken under the direction of YHWH, with the ideal of arriving in the presence of YHWH as the culmination. To be in the symbolic temple, to see the face of YHWH, as it were, implies to dwell in well-being, to be protected against enemies and to be satisfied with happiness. Included amongst those blessings is the privilege of being a confidante of YHWH, being taught his will and experiencing his goodness in 'length of days'. Psalm 27 should be understood in the context of the cluster as a text that acclaims the ideal of living one's life in YHWH's presence and which is focused on the goal of reaching that destination and encouraging fellow believers to persevere in the journey. Reflecting on YHWH's goodness, his instructions for the road of life, and the joy it brings, is part of that journey.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Author's contributions

P.J.B. is the sole author of this research article.

Ethical considerations

This article followed all ethical standards for research without direct contact with human or animal subjects.

Funding information

This research was completed whilst the author had access to a research fund in his name at the University of Pretoria (NRF 119158).

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the University of Pretoria.

References

Auffret, P., 1986, '"Yahvé m'accueillera", Étude structurelle du psaume 27', Science et Esprit 38(1), 97-113. [ Links ]

Barbiero, G., 1999, Das erste Psalmenbuch als Einheit: Eine synchrone Analyse von Psalm 1-41, p. 16, Österreichische Biblische Studien, P. Lang, Frankfurt am Main. [ Links ]

Birkeland, H., 1932, 'Die Einheitlichkeit von Ps 27', Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 51, 216-221. https://doi.org/10.1515/zatw.1933.51.1.216 [ Links ]

Botha, P.J. & Weber, B., 2019, '"The lord is my light and my salvation …" (Ps 27:1): Psalm 27 in the literary context of Psalms 25-34', Journal of Northwest Semitic Languages 45(2), 19-50. [ Links ]

Brueggemann, W. & Bellinger, W.H., 2014, Psalms (New Cambridge Bible commentary), Cambridge University Press, New York, NY. [ Links ]

DeClaissé-Walford, N.L., Jacobson, R.A. & Tanner, B.L., 2014, The book of Psalms (The New International commentary on the Old Testament), Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Goldingay, J., 2006, Psalms volume I: Psalms 1-41 (Baker commentary on the Old Testament), Baker Academic, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Gunkel, H., 1986[1926], Die Psalmen, 6th edn., Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen. [ Links ]

Hossfeld, F.-L. & Zenger, E., 1993, Die Psalmen I, Psalm 1-50, Echter Verlag, (Die Neue Echter Bibel 29), Würzburg. [ Links ]

Hossfeld, F.-L. & Zenger, E., 1994, '"Von seinem Thronsitz schaut er nieder auf alle Bewohner der Erde" (Ps 33,14), Redaktionsgeschichte und Kompositionskritik der Psalmengruppe 25-34', in I. Kottsieper, J. Van Oorschot, D. Römheld & H.M. Wahl (Hrsg.), Wer ist wie du, HERR, unter den Göttern? Studien zur Theologie und Religionsgeschichte Israels, Für Otto Kaiser zum 70, Geburtstag, pp. 375-388, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen. [ Links ]

Janowski, B., 2014, '"Womit soll ich dir entgegentreten?" (Mi 6,6), Gabetheologische Aspekte der alttestamentlichen Kultkritik', in B. Janowski (ed.), Der nahe und der ferne Gott, Beiträge zur Theologie des Alten Testament, 5, pp. 173-203, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Neukirchen-Vluyn. [ Links ]

Koehler, L. & Baumgartner, W., 1994, The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament (HALOT), ed. J.J. Stamm, Transl. M.E.J. Richardson, CD-ROM ed. (BibleWorks, v. 10.), Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Konkel, M., 2012, '"Dein Angesicht, Herr, will ich suchen" (Ps 27,8), Der Psalter als Schule des Gebets', Theologie und Glaube 102(3), 322-336. [ Links ]

Kraus, H.-J., 1978, Psalmen 1-59 (Biblischer Kommentar zum Alten Testament), Neukirchener Verlag, Neukirchen-Vluyn. [ Links ]

McCann, J.C., 2005, 'The shape of book I of the Psalter and the shape of human happiness', in P.W. Flint & P.D. Miller (eds.), The book of Psalms, composition and reception, supplements to Vetus Testamentum, 99, pp. 340-348, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Mowinckel, S., 2014a, Psalm studies, vol. 1, transl. M.E. Biddle, History of biblical studies, p. 3, Society of Biblical Studies, Atlanta. [ Links ]

Mowinckel, S., 2014b, Psalm studies, vol. 2, transl. M.E. Biddle, History of biblical studies, p. 3, Society of Biblical Studies, Atlanta. [ Links ]

Sommer, B., 2021, 'From confidence to confusion: Structure and meaning in Psalm 27', in R.A. Harris & J.S. Milgram (eds.), Hakol Kol Yaakov, The Joel Roth Jubilee Volume, pp. 352-382, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Van Zyl, A.H., 'The unity of Psalm 27', in I.H. Eybers, F.C. Fensham, C.J. Labuschagne, W.C. Van Wyk & A.H. Van Zyl (eds.), De fructu oris sui, Essays in honour of Adrianus van Selms, pp. 233-251, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Weber, B., 2001, Werkbuch Psalmen I (Die Psalmen 1 bis 72), Kohlhammer, Stuttgart. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Philippus Botha

prof.phil.botha@gmail.com

Received: 15 Mar. 2021

Accepted: 26 Mar. 2021

Published: 13 May 2021

1. Mowinckel's interpretation thus implies that the speaker in Psalms 27:4 is a priest and not a supplicant.

2. See the translation of Weber (2001:139) who translates the verb with 'um das Orakel zu erkunden in seinem Tempel'. Goldingay (2006:390) translates it as 'making request at his palace', adding in a footnote that the verb bāqar has this precise meaning only here. DeClaissé-Walford (2014:loc 5844) translates it as 'to inquire in the sanctuary', and says that the psalmist might have sought an oracle from a priest, or have sought asylum in the temple, but that it probably rather 'underscores that the psalmist inquires the Lord's will precisely because the Lord is the only trustworthy source of guidance and wisdom'.