Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

HTS Theological Studies

versión On-line ISSN 2072-8050

versión impresa ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.76 no.4 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v76i4.5616

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

The church in Nigeria and political economy of youth unemployment: A pragmatic approach

Olihe A. OnonogbuI, V; Nathan ChiromaII, V; George C. NcheIII, V; David C. OnonogbuIV, V

IDepartment of Political Science, Faculty of the Social Sciences, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria

IIDepartment of Children and Youth Ministry, Pan Africa Christian University, Nairobi, Kenya

IIIDepartment of Religion Studies, Faculty of Humanities, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

IVDepartment of Religion and Cultural Studies, Faculty of the Social Sciences, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria

VDepartment of Practical Theology, Faculty of Theology and Religion, University of Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Nigeria has over 57% of its population as youths. The nation is rich in human and mineral resources, yet the level of youth unemployment continues to rise and to pose serious socio-economic and political threats. The aim of this study was to highlight the strong link between the high level of youth unemployment and the rising tide of violence and criminalization of the public space in Nigeria. In other words, we argued that the youth routinely took out their frustrations in violent and criminal forms. The study was set in Aba, city of Abia state, which is arguably the largest commercial town in the south-east region of Nigeria. It is also synonymous with violent and criminal social breakdowns. This empirical study adopted a multi-phase sampling technique for the data collection procedure, including the distribution of questionnaires, extensive library research and personal observation. By implication, both primary and secondary sources were used. The results show that youth unemployment was on the increase and government efforts alone were inadequate to solve the problem. In conclusion, the all-hands-on-deck approach was advocated. This entailed that the visibility of the church at almost every level of community life, especially at the grass-root level must be used as a vital platform to reach the people. Thus, it was recommended that the church should actively tap into the multifarious professional capacities of her members and use them as resource persons to creatively tackle the problem of youth unemployment.

CONTRIBUTION: This article contributes to the concept 'faith seeking understanding'. It includes a systematic and practical reflection, within a paradigm in which the intersection of social sciences and theology generates a transdisciplinary contested discourse

Keywords: church; political economy; youth unemployment; youth; violence; crime; Abia State.

Introduction

Being young in Nigeria is very challenging. The youth unemployment rate in Nigeria, according to the Nigerian Bureau of Statistics (2018), currently stands at 23.1% in 2018 while the rate of underemployment is at 20.1%. This unemployment rate has been projected to hit 33.5% by 2020 (Carsten 2018; Premium Times 02 May 2019). For young people aged 15-35, the figures are grim: 55.4% of them are without work (Aljazeera 16 February 2019). Hence, young people, who are at the height of their potentials and talents, largely constitute the unemployed in Nigeria.

Consequently, youth unemployment is a major socio-economic and political problem in Nigeria because it involves the lack of resources and income, as well as an increase in criminalised and deviant behaviour especially in urban areas (Awognele & Iwuamadi 2010:2). It is also a moral problem because it is an aberration that emphasizes the social injustice that relegates the unemployed and highlights the inability and/or failure of the government to cater for the welfare of the citizenry. This means that the measures taken so far by the government have been inadequate to address the concerns of young people generally and youth unemployment in particular. Hence, the future of young people continues to be bleak.

In view of the above, the thrust of this study is that the Nigerian church has a role to play in the public space to buttress her concern for the holistic wellbeing of young people in the community. This is possible by the presence of the church that is felt in almost every nook or cranny of the society. In other words, the church is even closer to the people than the government in some places, giving her a central place in the lives and experiences of the people. In the light of the above, this research was undertaken with the aim of finding out if the church is doing enough in the social sphere or if the reality on the ground leaves more to be desired.

Contextualisation of terms

In this study, terms are given universal and contextual definitions and adapted to how they are applied to clarify the key concepts. The terms that require attention are: church, political economy, unemployment and youth.

Church: The church is a community of Christian believers whose mandate is to be the sign of the reign of God among His people. It is a microcosm of the larger community and closely mirrors the society. The church is called to showcase and model the love of God toward society and its needs and problems.

Political Economy: Igwe (2007:333) posits that this term refers to the scientific study of the reciprocal influence of economics and politics because it inevitably involves 'attentions to relations of production and the iniquities and imbalances in the national and global distributions of economic and political power'. In this study it is used to include the economic and political factors that contribute to entrenching the problem of youth unemployment in Nigeria.

Unemployment: As used in this study the term refers to the inability of a significant number of the productive labour force who are able and willing to work and to find jobs for a protracted period. The types of unemployment include seasonal, frictional, cyclical and structural unemployment (Adebayo 1999; Damachi 2001; Hollister & Goldstein 1994; Robert 1993; Sills 1995; Todaro 1992). Others are technological, residual and disguised unemployment.

Youth: There are various beacons that influence the definition of youth. These include age bracket, sociological and behavioural indices (Echebiri 2005:5; Weber 2015). The Nigerian youth charter defines youth as everyone within the 18-35 years bracket. In this study, they are aggregated within the 15-35 years bracket. This subset has the potential and capacity to stimulate economic growth, social progress and overall national development because they are the young, adventurous and energetic members of the society who are characteristically bold, resourceful, optimistic and fearless. The terms, 'young people' and 'youth' are used interchangeably.

Causes of youth unemployment in Nigeria

The causes of unemployment include:

1. Recession: When the economy is not growing and jobs are not being created, unemployment ensues and rises. A recessive economy is often caused by corruption and recklessness in public spending. For instance, Nigeria had economic recessions in the years 1991, 1995 and 2016 (Tijani 2017). However, the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) has confirmed that the 2016 economic recession was a full year recession, and the worst in the country's history since 1987. Combating recession is done through a prudent fiscal policy that includes incentives to invest and to spend money, including lower taxation and interest rates.

2. Over-Regulation: This is another cause of unemployment in Nigeria that results from too much paperwork involved in doing business and too many regulations that stifle job creation efforts, thereby hindering its expansion and ability to create more jobs. A good example of this is the current closure of the Nigerian borders, which continues to have a negative impact on businesses (see Rasheed 2020). Hence, it explains why unemployed people find it almost impossible to get work, especially among young people specified in the focus of this study. Characteristically, it leads to a two-tier economic system where those who are already employed have a job for life, and those who do not are unable to find one. By implication, there are too few jobs for the demand and the shortage leads to poverty and chronic unemployment.

3. Inadequate Skills: This occurs when the types of jobs in an area change and people without the right skills lose their jobs and are unable to find work because the new jobs are filled up with new people who possess the right skills. A technology shift that is structural in nature can cause this type of unemployment. It will constitute a wrong policy approach to keep the old jobs going because a lot of money will be wasted and the people will not be motivated to improve their situation. The right solution is to provide opportunities for training and re-training staff members.

4. Lack of Information: This occurs when people lack information about available jobs. Dissemination of information is fundamental in any market, including the job market. The obvious solution to this problem is to be able to bring information to the people who need it.

Other causes of youth unemployment in Nigeria, according to Ekwowusi (2002), include:

[M]ismanagement of the economy, inefficiency of government, monumental corruption, plundering of national treasury, government over spending and over subsidy, executive robbery either by the stroke of the pen or barrel of the gun. (n.p.)

Adebayo (1999) and Echebiri (2005) looked at it from the demand and supply angle. They argue that unemployment generally ensues whenever the supply of labour exceeds the demands for it at the prevailing wage rate and this is caused by rural-urban migration, which is better appreciated in the light of the data showing that by 2010 over 50% of young people in Africa will be residing in urban areas (Sarr 2000:34).

It is important to mention that the high level of corruption in Nigeria is another causative factor leading to youth unemployment.

The political economy of youth unemployment in Nigeria

Youth unemployment occasions a low rate of trading and industrial activity within the labour force. That is, the nation operates below its economic capacity and this directly impacts on families and livelihoods because young people who can scarcely meet their basic needs such as food, shelter and clothing tend to become dependants and/or engage in anti-social activities in order to meet these needs. This is expected in a social context that mirrors an absence of political will on the part of the leaders, absence of the culture of merit and flagrant corruption (Chigunta 2002; Onoge 2005; Ononogbu 2005). Little wonder what Achebe claimed 36 years ago that 'the trouble with Nigeria is simply and squarely a failure of leadership' (Achebe 1983), and is still the case in 2019.

In spite of a decade in which some African economies have experienced relatively high rates of economic growth, and the fact that the 2008 global economic predicament had only taciturn effects on most African economies, in many parts of the sub-continent unemployment among young people are progressively seen as the hard core of the development challenge (Ighobor 2017; World Bank 2006, 2009). This is the human face of the phenomenon of 'jobless growth' among young people, and undermines any possibility of realizing the much heralded 'demographic dividend' (Eastwood & Lipton 2011; USAID 2012). Consequently, Bennell (2000) and Momoh (1998) argue that since the livelihood needs and expectations of young people are not being met, they now constitute a huge economic burden, a depleting agent and a liability instead of a resource for economic growth. For instance, the youth are at the heart of 90% - 95% of violent conflicts in Nigeria (Omeje 2005:1). The United Nations Office for West Africa (UNOWA) (2008) and the Economic Report on Africa (2007:3-6) further reveal that young people who are able-bodied but unskilled, jobless and alienated, are often paid, armed and even drugged to foment trouble and create a state of anarchy in the polity in exchange for small amounts of money - together with the promise of recognition, loot and 'wives'. They survive by engaging in activities such as petty trading/hawking, casual work, stealing, pick-pocketing, prostitution, touting and other illegal activities and account for the many vagrants in the society. Furthermore, A World Bank survey in 2011 showed that about 40% of those who join rebel movements in Africa say they were driven by a lack of jobs (Ighobor 2017).

Methodology

Study area

This study was conducted in Aba, the major economic city in Abia State. Aba city lies along the west bank of the Aba River which is located in the south-eastern region of Nigeria. It is low-lying with a heavy rainfall of about 2400 mm/year and is especially intense between the months of April through October. Aba is a commercial city of international repute featuring a high concentration of small-scale industries and a number of sizable markets including the famous Ariaria International Market. Administratively, the city falls into two local government areas namely: Aba North and Aba South. Aba North has its headquarters at Eziukwu-Aba, while Aba South has its headquarters at Aba Town Hall. It is also a high residential area and host to a number of banks, industries and business enterprises which account for a large presence of young people. The 2006 population estimate for the city is 931 900 but according to the Nigerian Population Commission (2015), the last known population is 1 277 300; and if the population growth rate remains the same as it was between 2006-2015 (+5.57% per year), the population in 2019 can be estimated at 1 586 287, consisting of civil servants, traders, artisans and people engaged in various forms of services. There are also workers in the organized sector and vagrant youth. The study was carried out in Aba cosmopolitan area to purposefully include a cross-section of all perceivable social and economic segments of the city's population. Its advantage includes the fact that it combines high residential density, urban characteristics and a high population of young people in addition to a number of business interests.

Sample size

The sample was made up of 250 respondents. This cuts across students, clergy and lay workers, business men/women and traders, civil servants, self-employed and the unemployed. It excluded anyone who was not residing in the town. The youth were generally met either at home, on the street or in their respective places of work; others were met at the park. An Anglican, a Roman Catholic and a Pentecostal church (Redeemed Christian Church of God RCCG]) were sampled respectively. In all, 220 youth were randomly sampled. Ten leaders (clergy and lay workers) of the Roman Catholic, Protestant and Pentecostal Churches were sampled respectively bringing the number to 30 leaders of the church sampled in the town. Altogether, 250 questionnaires were distributed.

Sampling technique

A multi-phase sampling technique was used for the data collection procedure. This procedure included the distribution of questionnaires, extensive library research and personal observation. By implication, both primary and secondary sources were consulted in the course of the study. Data were analyzed using percentages and the analytical interpretative model was systematically used to explain the findings.

Instrument for the study, method of data collection and analysis

The instrument consists of four clusters: (1) general information which includes relevant socio-economic characteristics of respondents; urban residency status, unemployment/employment status, as well as job perceptions and preferences. (2) Scale of incidence of youth unemployment. (3) The link between youth unemployment and dysfunction. (4) Impact of government policies and projects on youth empowerment; and (5) perception of the effort of the church. The questionnaire was validated by a clergy and three scholars in the fields of religion, economics and sociology/anthropology. The questionnaire was also pre-tested in Nsukka town to certify the relevance of the items before they were taken to the field. Secondary data were collected from research reports and other published and internet materials.

Data presentation and analysis

Two hundred and fifty questionnaires were administered in the field but only 245 were validly filled out and returned. The response rate shows that 245 (98%) of the respondents duly filled and returned their questionnaires, while five (2%) were unable to return theirs. This high rate of returned questionnaires could be attributed to the intensified follow-up measures undertaken by the researcher. Consequently, the analysis will be based on the 245 validly completed forms.

Background variables

The socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents will be presented and they include: age, gender, occupation and highest academic qualification.

Age of respondents

The age of the respondents ranged from 18 to 58 and above years. These were arranged into an interval of 10 years each. The details show that out of the 245 respondents, the highest proportion of 91 (37.14%) fall within ages 28-37 years, closely followed by the 18-27 years range that has 77 (31.43%). Next is the 38-47 years group with 49 (20%), the 47-58 years range comes after them with 25 (10.20%) and the least is the 58 and above group with three (1.22%).

It, therefore, means that most of the respondents 217 (88.57%) are people within the age range of 18-47 years. It should, therefore, be noted that the larger number of respondents are within the youth stage which is very relevant to this study.

Distribution by gender

Questionnaires were distributed to both male and female respondents in the study area. The outcome shows that the number of males who participated in the survey were 142 which makes up about (57.96%) of the total respondents while females constituted 103 (42.04%). This implies that more males than females were available and participated at the time when the questionnaires were distributed.

Distribution by educational qualification

In this section, we were interested in finding out the highest educational qualification of the respondents.

The data indicated that the category with the highest frequency of 76 (31.02%) has obtained the West African Senior School Certificate Examination (WASSCE)/General Certificate Examination (GCE).

This group is followed by those with a first degree 73 (29.80%) and diploma 72 (29.39%) respectively. Others include First School Leaving Certificate (FSLC) 21 (8.57%) and second degree 3 (1.22%).

Imperatively, all of the respondents 245 (100%) have obtained some level of formal education and we did not encounter anyone who did not have even the most basic education. By implication, it can be taken at face value that all the respondents understood the issue at stake to some degree.

Distribution by occupation

The target was to find out the occupational status of the respondents. We found that 79 (32.24%) of the respondents were students at various levels of study. Civil servants constituted 50 (20.41%) and unemployed persons were 33 (13.47%). They are followed by people in different businesses and trade 32 (13.06%), the self-employed 28 (11.43%) and the clergy 23 (9.39%).

The fact that civil servants appear to be more than those in business and trade in a commercial city like Aba may not be unconnected with the fact that some business men/women and traders may have indicated that they are self-employed.

Substantive issues of the research

Consequent upon the restlessness and general dysfunction associated with the youth in recent times, youth unemployment has generated heated debate across the board in the society. The issues raised revolve around the causative factors, consequences and likely solutions to the problem. The bottom-line, however, remains that the youth are excluded from the machineries of social integration and development in Nigeria.

Based on the above premise, we will present and analyse data on the issue of youth unemployment and the role of the church based on the views of respondents on the scale of incidence of youth unemployment, the link between unemployment and dysfunction, impact of government policies and the perception of the effort of the church. With these research objectives as a guide, the respondents' reactions to the questions asked were analyzed allowing the respondents to state whether they 'strongly disagreed', 'disagreed', 'agreed' or 'strongly agreed'. We will find the interpretations below:

The scale of incidence of youth unemployment

A large number of the respondents, about 40.1% opined that they agreed that youth unemployment was a social problem that deserved attention. Another 25.4% strongly agreed. On the other hand, 20.3% disagreed that something needed to be done about it and 12.2% strongly felt that it was not a crucial socio-economic problem.

By implication, the larger proportion of the respondents was of the view that youth unemployment is a very serious socio-economic problem in Aba. This is consistent with extant literature on the issue (Awogbenle & Iwonmadu 2010; Echebiri 2005). The number of those who disagreed may result from the extended family system/communal lifestyle of the people which enables even adult dependants to be absorbed and supported by parents, siblings and other extended relatives is helping to cushion the impact of the problem among the people. This system tends to act as an insulator that shields people from stark realities so that an unemployed person may be well off on the patronage of other people. As such, he and/or she may not find anything wrong with not having a job when almost all he and/or she needs are met by other people. Another factor that could be responsible for this development is complacency among many young people to look for work after having faced repeated disappointment in the labour market. According to Ezemenaka (2018:112) this could explain the high and increasing levels of kidnapping for ransom and the number of criminalized and/or street youth in the city.

Link between unemployment and dysfunction

The data, 28.7% also supported the view that most of the respondents agreed that the level of youth unemployment in the city was directly proportional to the rate of youth dysfunction. However, 25.9% are of the opinion that the reverse is the case. This is again strongly contested by 23.5% of the respondents, while being strongly supported by 19.9%.

Again, we observe that the largest proportion of the respondents 28.7% was of the view that there is a link between youth unemployment and dysfunction in the city. This also agrees with relevant literature and data available (Olawale 2004:13; Omeje 2005:1). In all, 54.2% were in agreement while 43.8% disagreed that the link existed. It is important, therefore, to note that the difference between the opinions of respondents on the matter is not very wide. Again, could it be that the commercial nature of the city (i.e. almost everyone is ostensibly involved in something), gives the impression that the crime rate is unrelated to the unemployment level since everyone appears to be doing something to earn a living yet there is a recorded high and increasing rate of crime?

Impact of government policies on youth unemployment

The data also portrays that 32.2% of the respondents disagreed that there was any impact of government policy on youth unemployment. They are closely followed by the group that strongly disagrees 30.4%. However, 28.1% believe that they see the impact of government policies, while 7.3% strongly attest to the fact.

In this case, there is a resounding consonance with the views expressed by Achebe (1983), Chigunta (2002) and the International Labour Organization (ILO 2004). In concurrence too is the view of the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), (2004) that:

[T]he lack of detailed and empirical analyses on employment in national development policies may be attributed to the assumption that growth would automatically translate into more jobs, and to the lack of understanding of how the labour market works.

The importance of this observation is that there is a lacuna between government policies on paper and implementation. By extension, it stands to reason that the majority of people in the society feel that the government is merely scratching the surface of the problem.

Respondents' perception of the effort of the church

The survey data also portrays that 33.5% of the respondents agreed that the church was making some kind of effort in the social arena. This is followed by 30.1% who say that the impact of the church's effort in social action evangelism is yet to be felt. Then 18.2% strongly agree with the effort of the church, while 16.1% strongly disagree.

As is clear here, a larger number of people believe that the church is already doing something to step into the public space as against only being concerned with spiritual affairs. This category affirms that the church is not neglecting the socio-economic welfare of their members and the society. However, it is also clear that those who disagree with this position are equally not negligible. Hence, an additional survey will be needed to determine whether there is a correlation between the surveyed respondents opinions and active involvement in the church community. Onah, Okwuosa and Uroko (2018:3) articulate that the failure of the government to alleviate or eradicate poverty calls for all social actors to be involved in handling the issue.

Summary

The purpose of the study was to look into the problem of youth unemployment in Nigeria, with particular focus on Aba city in Abia state. Our specific concern in this regard was to determine the place of social service delivery in the evangelization effort of the church. This study therefore, was intended to appraise the role of the church in the Nigerian public space.

The target population comprised community residents in the city between ages 18 and above. A sample size of 250 respondents was selected through the cluster and simple random sampling techniques. A questionnaire instrument was adopted for the generation of data while tables, percentages and charts were used to present the data.

Major findings

The major findings of the study are as follows:

1. The data collected and analysed revealed that the majority of the respondents did not perceive youth unemployment to be a serious problem that required urgent attention.

2. It was also found that there is a high level of youth involvement in anti-social behavior in the city.

3. Many young people indicated an interest to be trained and/or acquire skills.

4. Our findings equally show that many respondents do not find much of a link between the level of youth unemployment and dysfunction in the society.

5. The data indicated that government policies do not have any direct, positive bearing on the lives of the people.

6. Government policies were found wanting mainly because the people were not integrated at the planning stage and the plans were not usually locality-specific.

7. We also found that a good number of the respondents believe that government is failing in its responsibility to provide social amenities and infrastructure for the people.

8. It does appear that one way or the other, the church is passively involved in the public space.

9. Our data also affirmed that some of the respondents were directly employed as teachers and health workers by the church.

10. Many of the respondents disagreed that the church should network with the government in any way. A good number believe that the politicians will corrupt the church leadership.

11. Almost all of the respondents agreed that getting involved in social action evangelism will not derail the church from its spiritual goals; rather it will boost its activities.

Recommendations

Based on the findings of the study, the following recommendations are made:

1. Government should integrate the people through the church in the planning and execution of projects that are locality-specific and relevant. This appeared according to the respondents to be a major reason why the government's impact was said to be inadequate. This is in line with the arguments posed by Ekwosi (2002) and Echebiri (2005).

2. The findings of the study also reveal that the church would need to serve as a data resource base for the government and other non-governmental organizations that are interested in reaching the people. This recommendation is submitted on the strength of the fact that the church has a more visible presence than the government at the grass root level, and churches have also been involved in one way or the other, but will need a more consolidated effort that focuses on young people.

3. The church should set up skill(s) acquisition centres using its members in various professional fields as resource persons. This will serve to: (a) engage the youth productively and creatively; (b) give them an honest means of livelihood; and (c) afford the church a unique opportunity to witness to them. The church should treat youth unemployment in Nigeria as a crosscutting matter by looking at the responsibility of the different actors.

4. The power and the potential of young people should be tapped by churches in providing self employment opportunities as highlighted in the findings of this study. There is therefore an urgent need to create opportunities for youth, with tremendous potential impact.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Prof. Malan Nel for his intellectual guidance and for offsetting the article processing cost for this article.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work.

Ethical consideration

This article followed all ethical standards for research without direct contact with human or animal subjects.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

References

Achebe, C., 1983, The trouble with Nigeria, Fourth Dimension Publishers Co., Enugu. [ Links ]

Adebayo, A., 1999, 'Youth unemployment and national directorate of employment self-employment programmes', Nigerian Journal of Economics and Social Studies 41(1), 81-102. [ Links ]

Awogbenle, A.C. & Iwuamadi, K.C., 2010, 'Youth unemployment: Entrepreneurship development programme as an intervention mechanism', African Journal of Business Management 4(6), 831-835. [ Links ]

Bennell, P., 2000, 'Improving youth livelihoods in SSA: A review of policies and programmes with particular emphasis on the link between sexual behaviour and economic well-being', Report to the International Development Centre (IDRC), viewed 23 May 2018 from https://hivhealthclearinghouse.unesco.org [ Links ]

Carsten, P., 2018, Nigeria's unemployment rate rises to 23.1 percent in Q3, CNBCAFRICA, viewed 22 January 2020, from www.cnbcafrica.com [ Links ]

Chigunta, F., 2002, 'The socio-economic situation of youths in Africa: Problems, prospects and options', A paper presented at the youth employment summit, Alexandria, pp. 1-13. [ Links ]

Damachi, N.A., 2001, 'Evaluation of past policy measures for solving unemployment problems', Bullion Publication of the Central Bank of Nigeria 25(4), 6-12. [ Links ]

Eastwood, R. & Lipton, M., 2011, 'Demographic transition in Sub-Saharan Africa: How big will the economic dividend be?', Population Studies 65(1), 9-35. [ Links ]

Echebiri, R.N., 2005, 'Characteristics and determinants of urban youth unemployment in Umuahia, Nigeria: Implications for rural development and alternative labour market variables', A paper presented at the ISSER/Cornell/World Bank conference on shared growth in Africa, Accra, 21-22 July. [ Links ]

Economic Report on Africa, 2007, Economy Watch, 2009, viewed 16 July 2019, from https://www.economywatch.com/unemployment/countries/nigeria.html. [ Links ]

Ekwowusi, S., 2002, 'Nigeria: Journey to the depths of hope', Thisday, viewed 22 July 2019, from http://allafrica.com. [ Links ]

Ezemenaka, K.E., 2018, 'Kidnapping: A security challenge in Nigeria', Journal of Security & Sustainability Issues 8(2), 111-124. https://doi.org/10.9770/jssi.2018.8.2(10) [ Links ]

Ighobor, K., 2017, 'Africa's jobless youth cast a shadow over economic growth: Leaders put job-creation programmes on the front burner', Africa renewal: Youth & unemployment, viewed 05 February 2020, from www.un.org/africarenewal/ [ Links ]

International Labour Organization (ILO), 2004, Facts on child labour, Geneva. [ Links ]

Mkandawire, R.M., 1996, 'Experiences in youth policy and programme in commonwealth Africa', Lesotho Social Sciences Review, 4(1), 69-94. [ Links ]

Momoh, A. 1998, Area boys and the Nigerian political crisis. Paper presented at the Empowerment Workshop in Sweden. [ Links ]

National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), 2018, Labor force statistics (vol.1): Unemployment and underemployment report, viewed 06 February 2020, from nigerianstat.gov.ng [ Links ]

Nigerian Population Commission, 2015, viewed 07 March 2019, from https://population.city/nigeria/aba/ [ Links ]

'Nigeria's unemployment rate hits 33.5 percent by 2020-Minister', Premium Times, 02 May 2019, viewed 22 January 2020, from https://www.premiumtimesng.com [ Links ]

Okorie, J.U., 2000, Developing Nigeria's workforce, Page Emarons Publishers, Calabar. [ Links ]

Olawale, I., 2004, 'Youth culture and state collapse in Sierra Leone: Between causality and casualty', Paper presented at UNU-WIDER conference, Helsinki, 3-6 June 2004. [ Links ]

Omeje, K., 2005, 'Youths, conflicts and perpetual instability in Nigeria', paper presented at the workshop on capacity-building for youth peace education and conflict prevention in Nigeria, Organized in Jos, Nigeria by the Africa Centre, University of Bradford. [ Links ]

Onah, N.G., Okwuosa, L.N. & Uroko, F.C., 2018, 'The church and poverty alleviation in Nigeria', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 74(1), 4834. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v74i1.4834 [ Links ]

Onoge, O.F., 2005, Crime and control in Nigeria, viewed 30 April 2018, from http://www.waado.org/youthaffairs/youth_essays/onoge_keynote [ Links ]

Ononogbu, D.C., 2005, 'The church and the youth', Unpublished M.A. Project. Department of Religion, University of Nigeria, Nsukka. [ Links ]

Rasheed, A., 2020, 'Nigeria's border closure: Pros, cons and consequences', The Punch, viewed from 02 January 2020, from https://punchng.com/nigerias-border-closure-pros-cons-and-consequences/ [ Links ]

Robert, T., 1993, 'What have we learnt from empirical studies of unemployment and turnover?', The American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings 83(2), 110-115. [ Links ]

Sarr, M.D., 2000, 'Youth employment in Africa', A paper presented at the UN Secretariat, New York, NY, 25 August 2000. [ Links ]

Sills, D.L., 1995, International encyclopedia of social studies, vol. 5, pp. 50-54. Nork York: Macmillan Free Press. [ Links ]

Tijani, M., 2017, 'Official: 2016 recession is Nigeria's worst decline since 1987', The Cable, viewed 05 February 2020, from www.thecable.ng [ Links ]

Todaro, M., 1992, Economics for a developing world, 2nd edn., Longman Group, U.K. Limited. [ Links ]

United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), 2004, 'Environment-friendly macroeconomic policies', Joint ILO-ECA position paper prepared for the extraordinary summit of the African Union on employment and poverty alleviation, Ouagadougou, 3-9 September 2004. [ Links ]

United Nations Office for West Africa (UNOWA), 2008, viewed 02 July 2019, from https://www.un.org/unowa [ Links ]

Weber, S., 2015, 'A (South) African voice on youth ministry research: Powerful or powerless?', HTS Theological Studies 71(2), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v71i2.2973 [ Links ]

'Young and unemployed in Nigeria: Why joblessness is such a huge problem in Africa's most populous nation', Aljazeera: Counting the Cost, viewed 22 January 2020, from www.aljazeera.com [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

David Ononogbu

daveononogbu@gmail.com

Received: 11 June 2019

Accepted: 25 Mar. 2020

Published: 19 Oct. 2020

Project Leader: Malan Nel

Project Number: 02331810

Description: This article forms part of the research project, 'Congregational Studies' of Prof. Malan Nel, Department Practical Theology, Faculty of Theology and Religion, University of Pretoria.

Appendix

Data presentation and analysis

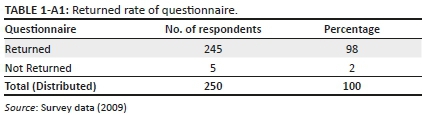

Two hundred and fifty (250) questionnaires were administered in the field but only 245 were validly filled out and returned. The response rate is shown in Table 1-A1 below:

In Table 1-A1 above, we see that 245 (98%) of the respondents duly filled and returned their questionnaires, while five (2%) were unable to return theirs. This high rate of returned questionnaires could be attributed to the intensified follow-up measures undertaken by the researcher. Consequently, the analysis will be based on the 245 validly completed forms.

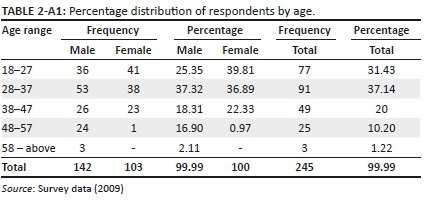

Age of respondents

The age of the respondents ranged from 18 to 58 and above years. These were arranged into an interval of 10 years each. The details are given in Table 2-A1 below:

We gather from Table 2-A1 that out of the 245 respondents, the highest proportion of 91 (37.14%) fall within ages 28-37 years, closely followed by the 18-27 years range that has 77 (31.43%). Next is the 38-47 years group with 49 (20%), the 47-58 years range come after them with 25 (10.20%) and the least is the 58 and above group with three (1.22%).

It, therefore, means that most of the respondents 217 (88.57%) are people within the age range of 18-47 years. It should, therefore, be noted that the larger number of respondents are within the youth stage which is very relevant to this study.

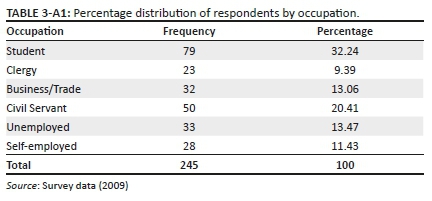

Distribution by occupation

This target here was to find out the occupational status of the respondents. Table 3-A1 gives us a picture of this.

This table shows that 79 (32.24%) of the respondents were students at various levels of study. Civil servants constituted 50 (20.41%) and unemployed persons were 33 (13.47%). They are followed by people in different businesses and trade 32 (13.06%), the self-employed 28 (11.43%) and the clergy 23 (9.39%).

The fact that civil servants appear to be more numerous than those in business and trade in a commercial city like Aba may not be unconnected with the fact that some business men/women and traders may have indicated that they are self-employed.