Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

HTS Theological Studies

versión On-line ISSN 2072-8050

versión impresa ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.76 no.4 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v76i4.5885

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Religious statecraft: Constantinianism in the figure of Nagashi Kaleb

Rugare Rukuni

Department of Christian Spirituality, Church History and Missiology, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The Himyarite invasion of 525 CE by Kaleb of Aksum was a definitive war in the narrative of global religion and politics. The accounts surrounding the war corroborate the notion of an impressed Constantinian modus of establishing religious statecraft. Whereas there has been much anthropological and archaeological work on the South Arabian-Aksumite relations from the 4th to the 6th centuries, revisionism in perspective of literary sources and respective evidence retains significance given the dynamism of Ethiopianism as a concept. Implicative document analysis, cultural historiography and archaeology of religion are relevant methods used in this study. There are parallels between Kaleb's new Zion agenda and Constantine's nova Roma persona, both resembling an emergent Christian-religious state. It is from this religious (Christian) state that a geopolitical policy that defined the trajectory of their respective nations emerged. The replete epigraphy and literary evidence on Ethiopia and its Byzantine connection aggregately affirms the explicit existence of a Christianised foreign policy.

CONTRIBUTION: The research revises the narrative of Ethiopian Christianity with a lens of political-religious dynamics thereby contributing to the field of theology and history.

Keywords: Christian history; Kaleb; Constantinianism; religious statecraft; Ethiopia; Himyar; Byzantine-Persian war.

Introduction

The concept of religious statecraft is a generic lens for decoding the geopolitical dynamics and domestic political religious complex of nations. From the perspective of reviews on the Christian empire of Byzantine Rome and the kingdom of Ethiopia, a comparable narrative is deductible. The kingly personality of Kaleb and Ella Asbeha when read against the background of Constantinian religious-political policy becomes enhanced. Kaleb in his projection postured aggregately as a Constantine, asserting his regional dominance (Bowersock 2013:76; Phillipson 2012). These claims were a continuum of Ezana's assertion of control over Himyar.1 The resurgence of Judaism in Himyar was a catalyst to a war that basically would be religious (Bowersock 2013:77). The Christian-political matrix in Ethiopia found a match in the Himyarite establishment. The Aksumite Nagashi (king of kings) claimed the titles of King of Himyar, Saba, dhu-Raydan, Tihama and Hadramawt as shown in RIE vol. 1, nos. 269, 286 (1991-2000:362-363, 385-386).

In retaliation, the Himyarite monarch Abikarib 'Asad, in inscriptions now dated to have been from the late 4th century CE, also claimed to be King of the tribes, that is, Saba, dhu-Raydan, Hadramawt, Yemen, the Tawd and Tihama (Robin 2009:47-58). This claim was buttressed later on by Yusuf the 'king of the tribes' with the support of local clans such as the Y az'anids. Correspondingly, the Y az'anids had the support of the Banü Gadanim of Märib and the Ghayrnän from Sanaa (Nebes 2010:43). This implicatively denotes the struggle between Himyar and Aksum as one that additionally drew from issues of native sovereignty. The manner of warfare that also included trade blockades on important trade routes can be decoded as to have been an attack upon the essential nature of the Aksumite-Himyarite commercial connection; however, as an overall theme, religion covers the battle narrative.

There were many indications of clashing statecraft; Yusuf, who possibly embellished a Jewish messianic cult (Baron 1957:3:63-69, 257-260; St. Gregentius The Dialogue with Herbanus ed. Berger 2012:124-126; Shahid 1976:149), was here posing a challenge to the Judeo-Christian establishment that was represented by Kaleb. As the 'New Zion', Ethiopia's Christian statecraft was parallel to its geopolitical ambitions in the region; this is more so because Kaleb sought the continuation of the antique claims over Himyar - 'their inheritance a land of their enemies' (Book of the Himyarites 46a; ed. & transl. Moberg 1924:136; Shahid 1976:148-149).

Describing the Himyarite war as a narrative of confluence between religious statecrafts is a logical possibility in the perspective of the preceding observations.

Methodology

The main method was document analysis, which implies systematic evaluation and review of documents. This enhanced interface with primary sources (cf. Bowen 2009:27; Ritchie & Lewis 2003). To enhance the discussion, cultural historiography, which establishes the multilayered cultural background to the narrative, was compositely used (Danto 2008:17). In addition to cultural historiography, there was an engrained concept of enculturation and self-definition applicable in studying religious-political matrixes (Rukuni 2018:156).

Reference is made to the archaeology of religion, given the various rock inscriptions and monuments that are found in Ethiopia and South Arabia (Insoll 2004:59). In addition, archaeology has the significant role of discrediting or affirming respective texts on Ethiopia such as the Kebra Naghast (Insoll 2004:61; Yamauchi 1972:26).

As correspondent to the contemporary dynamics that defined Constantinianism - a convolution of imperial politics and religion - aggregately propped up by ecclesiastical propaganda as reflected in Eusebius and Lactantius' works, respectively, Ecclesiastical History, Life of Constantine, the Orations of Constantine and Death of the Persecutors, this research implies a decoding of historical narratives with the then prevalent lens of the conquering pious against the subdued vile apostates (ed. Schaff 1885c). Whilst attempting to establish a standard historical evaluation of facts, this developed bias that reflects the influence of Eusebian ideology is implied upon the deductions made within the corpus narrative (cf. Ferguson 2005).

Inceptive persecution

The claim to imperial power as reflected in the titulature over the same regions is an explicit index to the impending war that brewed between Aksum and Himyar. It seems correspondent to the adoption of Cristianity in Aksum Himyarites became Judaic. This theory now affirmed with archaeological evidence deconstructs the notion that the Judaised Christianity that characterised Ethiopia originated in South Arabia. The possible rise of Judaism in the late 4th century CE is attested to by a Himyarite seal that is engraved with a Sabaic name and the menorah (Robin 2004:831-908). In an affirmative deduction, the epigraphic evidence is reinforced by the martyrdom accounts as recorded in the Ethiopian Synaxarium, Book of the Himyarites and the Martirum Arithae. The first account relates to the martyrdom of a certain Azqir who identifies Jewish rabbis as in charge of his inquisition (Beeston 2005:113-118).

Azqir was from the city of Najran, and he was reportedly killed there; coincidently the persecutions under the Himyarite King Masruq [the comber], dhu Nuwas [long-haired], Yusuf Asar Yathar [Joseph] were also from the town of Najran (Robin & De Maigret 2009; Book of the Himyarites, ed. & transl. Moberg 1924). The persecution of Christians ignited the dynamic changes that stemmed from regional and aggregately global war. From the perspective of how Ethiopia had adopted Christianity and underwent the process of a royal conversion as reflected in Ezana, the involvement of Ethiopia in a region that it had initially claimed to have control over is implicative. Perhaps, the most deductive way to deduce the involvement of Ethiopia is a retrospective reference to Constantine's interactions with Shapur II (VC 4.8-14; Cameron & Hall 1999:156-158; Haas 2008:101).

Constantinian crusades against persecutors: A contextualising comparison

The background to the protracted war between Rome-Byzantine and Persia was the persecution of Christians within Persia. In addition, a connected matter relates to how the persecution of Christians in Persia was concurrent with the Constantinian momentum of the Christianisation of Rome (Long 2013). The reality of a Byzantine imperial-ecclesiastical establishment that had emerged from the internal rivalry between pagan Licinius and Christian Constantine, and the ideological divergence from the pax deorum and vetus religio [peace of the gods and traditional religions] as held by the persecuting emperors Valerian and Diocletian implied that a clash with a regional anti-Christian power would be inevitable (Cameron & Hall 1999:114; Eus. VC 2.59-60; Lact. DMP 48.6; Lee 2006b:164; ed. Schaff 1855b:490). In a parallel review, the clash between Ethiopia and Himyar as precipitated by the persecutions in Najran was against the background of the Christianisation of Ethiopia and the royal conversion of Ezana (Kaplan 1982:28).

When reflecting on how Constantine reacted to the Persian persecution or rather how he used it as an excuse to engage in an offense against the Sassanians, the Ethiopian attack on Himyar becomes deductible in a parallel perspective. Whilst Constantine's claims upon Persia were limited to disputed borders, such as the Roman stronghold of Nisibis, the extended claims for foreign intervention was the role of Constantine as arbiter of Christendom (Fowden 2006:392). However, the case of Kaleb against Yusuf/Masruq was more concrete, as Ethiopia had been involved in the Christianisation of Himyar, as per the initial engagement of Ethiopia and Himyar during the period 518-522 CE (Gajda 2009:47-58).

In addition to that, the imperialist claims on either side made the attack on Christianity an act of hostility. The Christianisation of Ethiopia had been effected through a royal conversion and the end result was a substantial religious-political establishment that would imply a connection between the clergy and the polity of the nation. Although much of the hagiographies and records of the ascetics and clergy relate to the medieval era, the incident involving Frumentius2 reflects on the possible King-Bishop relationship in the 4th century CE related to Christianity in Ethiopia (Binns 2017:40-44). The independence from Byzantine orthodoxy as seen in non-conformity to the directives of Constantius and the adoption of a non-Chalcedonian stance on the Nestorian controversy was at the largesse of Ethiopian independence from Rome (cf. Hendrickx 2012). This can be inferred from the case of Vandal Africa (cf. Whelan 2018), where the guarantor of the autonomy from Byzantine orthodoxy was the Negus establishment; hence, the political-religious impetus existent between the Negus [King] and Abuna [Bishop] could be catalytic in advocating for a holy war.

Amongst the sources for the persecutions of Najran and the resultant war between Himyar and Ethiopia are the Martyrdom of Harith, Martyrion Arethas (Greek) and the Syriac letter of Symeon of Beth Arsham and the Book of the Himyarites. Symeon of Beth Arsham's letter is an eyewitness account (ed. Brooks 1923:137-158). Much of the accounts read out thematically the same: Yusuf wanted to eliminate Christianity by eradicating churches or rather making them synagogues and exposing Christians to enforced conversions to Judaism. His main persecution was on the influential Christian inhabitants of Najran as recounted in the Book of the Himyarites (ed. & transl. Moberg 1924). Comprehensively prior to this, Yusuf had been involved in a planned repression of Christians and their Aksumite counterparts in the regions of Zafär, Najrän, Märib, the Tihäma and Hadramawt (Nebes 2010:40). The competing Byzantine and Persian interests on the whole Arabian Peninsula entailed some diplomatic engagements between the Persians and the Byzantines through their proxies.

Diplomacy and the religious implications

The alliances were consequently drawn along religious grounds. Yusuf sent a letter to a meeting that was convened at Ramla where present was sheikh al Mundhir, the Persian client monarch; Abramios, a Byzantine ambassador; and Symeon of Beth (Bowersock 2013:89). It has to be noted that Yusuf's predecessor Ma'dikarib Ya'fur had a cosy relationship with the Christians and was inclinedly pro-Byzantine (ed. Brooks 1923; Shahid 1971:XXVII, 6-10; Symeon of Beth). Ma'dikarib Ya'fur maintained hostilities against the pro-Persian Lakhmid ruler, Mundhir III, whilst he forged alliances with Roman proxies such as the Bedouin; hence, Yusuf was reflective of a shift in Himyarite foreign policy (Beaucamp, Briquel-Chatonnet & Robin 1999:75).

This brings up the subject of wider diplomatic implications on the Himyarite-Aksumite war, which embroiled the greater world. From a perspective that derives from the Byzantine imperial policy, certain observations have to be made that justify the timeous Christianisation of Ethiopia as the indicator needed for Byzantine foreign policy in the Red Sea. Constantine had incited the conflict with the Persians as a result of imperial conflict so as to determine the uneasy balance of power in the East (Fowden 2006:392). However, it should be noted that there were other borders in various regions. A significant element of this argument is the war with the Barbarian tribes, between Justin and Justinian conquest with religiously divergent groups was composite to Roman foreign policy (Procopius, Wars, Book 5.10.29, ed. & trans. Dewing 2017:5:10; ed. Pohl 1997).

From reconquests with Homoian Vandals in Africa, and challenges with unfamiliar terrain within Berber territory, to Gothic incursions, it appears Roman martial policy's expansive scope was a stretch upon the resourcefulness of the empire (Lee 2006a:118). It seems that amongst Roman-Byzantine threats, the most prominent remained the Persians, even as evidenced by the largest Byzantine force assembled in 503 CE by the emperor Anastasius to counter the Sassanid invasion of Mesopotamia and the ensuing assaults - (ed. & trans. Dewing 2017:1:20-22; cf. Haldon 2011; Procopius, Wars, 1.13-14; Wright 1882:38, 57-58, 63; Joshua the Stylite Chronicle, 54, 69, 79).

The conflict had an explicitly religious dimension, as the threat to Byzantine Christiana Imperium (Latin) (Christian imperial establishment) was the Zoroastrian magical practises of Sassanid Persia. Persia's foreign policy was also extensively engaging significant parts of Arabia, and hence, as a counter measure, the imperial Roman influences had to be commensurate. Roman policy transcended the Himyarite conflict; however, there was an apparent tilt of power in favour of the Persians. Therefore, alliances had to be made to counter the growing influence of Persia. Religion would be a key determinant in the choice of allies as resonant in Justinian's proclamation, mentioned by Ure (1951) that:

[T]he first and greatest blessing for all mankind is the confession of the Christian faith … to the end that it may be universally established and that … holy priests of the whole globe may be joined together in unity. (p. 122)

Extensive Roman Christian foreign policy: The case for an Aksumite alliance

The declaration by the emperor Justinian has several implications that are an index of his foreign policy, the first being the emphasis upon the imperial orthodox establishment. The second is how the imperial orthodox establishment was defined by an oecumene [ecumenical or universal agenda] (Hendrickx 2017:10). This entails that the unity derived within Christendom was to characterise the world or rather the conceived empire. This was synonymous with Constantine's Bishopric claims that encompassed the empire and without (VC 4.24; ed. Schaff 1885a:826). This surely had been the sentiment fuelling the continuum of conciliar developments within Christianity as Constantine and the same notion would guide the Byzantine foreign policy. This directly shows how a Roman-Aksumite alliance would be inevitable. The Byzantine Empire was surrounded aggregately by pagan Barbarians or non-conformant Christian confessions, and hence to find common Christian cause could guarantee political-military alliances from fellow Christians (Allen 2001:820-828).

As a consequent of the foreign policy of the two empires, the Persians and the Byzantines, there was a clash regarding their client connections. Later in 580 CE, a Jafnid ruler al-Mundhir ibn al-Harith was crowned a client monarch of the Byzantines. These Jafnids who are associated with the Ghassanids were the Roman check and balance upon the Byzantine Syrian-Eastern frontier, thereby securing the Byzantine tax base. The Jafnids were directly involved in the Byzantine-Persian war, as they contributed military units to the Byzantine army in assaults on Sassanians. Indirectly, they clashed with the Sasanian proxies such as the Nasrids. A similar relationship as that with the Jafnids was secured by the Byzantine with the Kinda tribe (Shahid 2002).

The Sasanian Great King Kavadh is also reported to have had contact with Kinda (Bosworth 1983:593-613). The Nasrids were Lakhmids from al-Hira (Kister 1968:143-169).

In addition to the Persian alliance, they had local alliances within the Peninsula and further East. Masruq Ash'ar's Nasrid connectionand his explicit advice to al-Mundhir, the Nasrid monarch, regarding the extermination of Christian subjects was an apparent provocation to a Byzantine response (Al-Assouad 2019; Bosworth 1983:600-601; Kister 1968:144-149). The narrative reads as a repetition of the essential spark to the protracted war between the Sassanians and Byzantine-Rome. The call to exterminate Christians, who were seen by both sides of the conflict as an extension of the nations with an explicit Christian-political establishment, was an outright act of war. Parallel to Constantine's situation with Shapur II, the explicit posturing by Justin as a propagator and custodian of the ecumenical orthodoxy establishment entailed that hostilities against Christianity were directly against the Byzantine empire. Hence, Yusuf/Masruq was extendedly an enemy of Rome and correspondingly his allies against Christianity were embroiled consequentially. Whilst this is the perspective derived from a review of the Byzantine position, an intrinsic look at Ethiopia and the preceding developments in the 4th century CE imply the same effect regarding the antagonism with Yusuf/Masruq. The call to arms by Byzantine extended to Ethiopia was possibly the realisation of the already catalytic religious hostilities between an upcoming Christian empire and a Judaised political establishment.

Byzantine foreign policy in the Red Sea implied connections within both the Arabian Peninsula and the Aksumite east African highlands. The Arabian interests primarily can be argued to have been an outgrowth of the intentions to neutralise the Persian influence. Correspondingly, the Aksumite alliance was possibly consequent of the geopolitical significance of Ethiopia within its region and its identification with Christianity. Byzantine overtures were realised by the dispatch of Nonnosus as the Aksumite ambassador (Nonnosi Fragmenta 1.p. 179 Photius Bibl. Cod. 3; Berti 2019) (Bowersock 2012:1-10). Nonnosus represented a series of embassy dispatches by a succession of emperors that emanated from Anastasius, Justin and then Justinian. Anastasius had sent an Euphrasius (PLRE II. Euphrasius 3, Martindale 1992:425) to the Arabian Kindite monarch Harith. Harith was a Hujrid, and his kingdom was within central Arabia (Bowersock 2013:137).

The settlement came as peace treaty following the Arabian invasions of Phoenicia, Syria and Palestine. The Byzantine alliance with the Hujrids became more relevant with the nullification of peace between Persia and Byzantine by the Shah Kawad in 502 CE (Shahid 1989:127-129). This is because Persia had significant alliances within the Arabian Peninsula with the Nasrids. The conference at Ramla took place against the backdrop of uneasy relations between Persia and Byzantium as a consequence of the war engagement through proxies. From a deductive viewpoint, Byzantium was in a position of aggregate weakness; they had to ransom captured captains (Timostratus and John), and one of their client monarchs was killed by the Persian proxy al Mundhir (Bowersock 2012:285; ed. & trans. Dewing 2017:1:27; Procopius, Wars 1.17.44). In light of the previously discussed observations, the alliance with a dominant regional power as the Aksumites who had considerable control in the strategic and influential Kingdom of Himyar was redemption on the part of the Byzantines.

Abraham had been sent by the emperor Justin to ransom Timostratus and John the captives of al Mundhir the Nasrid Persian proxy (Evagr, HE IV.12; eds. Bidez & Parmentier 1898:162).

Within this respective mission, Abraham was the Byzantine delegate at the conference at Ramla in 524 CE.

Nonnosus, the son and successor to the Byzantine Red Sea diplomatic front, was assigned a dual mission to the Arabian Kinda and to Aksum. Nonnosus' mission was the one that brought out to view the magnanimity of Kaleb the Judaised Christian monarch RIE vol. 1. no. 191 (1991-2000:272-273). The manner in which Nonnosus glosses in his accounts regarding his encounter with the Aksumite monarch implies a certain level of geopolitical eminence of his reign (cf. Bowersock 2012). The Byzantine alliance with Auxoumis was of mutual benefit to the empire (Procopius, Wars I.19; ed. & trans. Dewing 2017:1:30-32).

At the conference that had been attended by Abraham, Yusuf/Masruq had boasted of his genocide on Najran Christians. The letter read out the accounts of the Christians' death and their testimony (Bowersock 2013:90).

The King Yusuf had the backing of certain local tribesman, Yazanids, and the hostilities that he had inflicted upon Najran had ranged from trade blockades and correspondingly a siege that consummated in pillaging (Nebes 2010:45).

This had an obvious effect upon the audience based on their religious conviction and side in the Byzantine-Persian conflict. The Persians who had persecuted Christians as an act of subsequent provocation between Sassanians and Byzantium would find common cause with Yusuf. Given that the Jewish sheikh al Mundhir was a Persian proxy, the Himyarite monarch can be seen as seeking international attention from possible allies upon the Peninsula. For Abraham and the cleric Symeon of Berth Arsham, the opposite was true. Symeon would spread these horrible tidings to all Monophysite Christianity; this was a call for holy war (Shahid 1976:143). The actions of Yusuf against the Najran Christians were later resented across the spectrum of religious thought; it would appear even in the Quran, the martyrs are remembered (Ali 1955-2015:728; Nebes 2010:49; Quran Surah 85.4). The expression of the Quran shows solidarity for the assault against the Himyarite, as it labels them persecutors of women and children:

Those who persecute the believing men and the believing women and then repent not, for them is surely the punishment of Hell, and for them is the punishment of burning. (Quran Surah 85:11; Ali 1955-2015:729)

This assertion is derived from Nebes (2010) and from the understanding that the Quran like the Hadith derives from the background of 6th century CE dynamics upon the Arabian Peninsula. This was a scenario that would reveal the relevance of the symbiosis between piety and power in early Christianity; there was need for a Constantinian figure who would rise to defend Christianity on the Arabian Peninsula.

Epics of religious warfare: A clash of proxies, monarchs and faiths

The invasion of Himyar in 525 CE by Kaleb was not the first; this was a subsequent event to emphatically retain power upon the Peninsula. There had been a preceding invasion in the year 518 CE; this had seen the installation of an Aksumite client monarch, Madikarib Ya'fur (Beaucamp et al. 1999:75-76; Gajda 2009).

Evidence for the vassal ship of Himyar to Aksum is corroborated by the Arabian inscriptions that mention a monarch Marthad'ilan Yanuf who reigned in the years 504-509 CE. There is evidence of a Christian Marthad, son of Abdukulal (Bowersock 2013:93). In addition, there is the chronicle of John Diakrimenos to attest to the subservience of Himyarites (Gajda 2009:73-81).

According to the chronicle, the Himyarites upon being Christians requested for a bishop and a certain Silvanus was appointed in the same manner in which Frumentius was appointed for Aksumite Christianity (Book of the Himyarites; ed. & transl. Moberg 1924). Hence, this would imply that the initial invasion of Ethiopia was to buttress the power of the Christians, thereby making Madikarib Yafur the successor of Marthadilan Yanuf (Bowersock 2013:94). This observation builds into a narrative correspondent to the Book of the Himyarites that relates a Jewish persecution of Christians by Yusuf. This could have been an attempt to regain the kingdom that was now characterised by a new religion that corresponded to other challenging powers such as Ethiopia. The invasion of Himyar on the part of Ethiopia should be deduced as consequent of a mutually political-religious agenda; it was an issue of confessional solidarity to support Christian brethren in Himyar just as it was irredentist foreign policy characterising Ethiopia in the late 3rd century CE (Bowersock 2013:95; Jamme 1966:39). The thin line between a religious and political foreign policy resonates with Constantinian wars.

Kaleb commemorated his initial invasion of Arabia with an inscribed stele at Aksum in what is called the musnad script; this inscription forms part of the continuum of imperialist claims as performed by Ezana the first Christian emperor (ed. & transl. Moberg 1924:3; RIE vol. 1, no. 191, 1991-2000:271-274). The inscription corresponds with the Book of the Himyarites such as in the mutual identification of Hayyan or Hyona as Kaleb's general. The inscription mentions a shrine that the Negus built in Himyar at QN'L to the honour of the Son of God. There is also a possible reference to the cathedral Kaleb built at Aksum (Dillman 1865:1174). The ecclesiastical-political nature of the conflict is reflected in how Justin the Byzantine emperor sent the call to arms through the Alexandrian patriarch Timothy (Malalas, Chron. 18.15; Jeffreys et al. 1986:433-434). The message from Byzantium implied the religious nature of the conflict as the emperor implored the Negus by the Holy trinity, to fight the abominable and criminal Jew so as to ensure Yusuf was an anathema.

The two observations regarding the communication of Justin to Kaleb are significant; they connect the conflict to dynamics that characterised 4th century CE Christianity. The designation of the communication through a cleric, the patriarch of Alexandria, Timothy brandishes the war with an orthodoxy agenda. Whereas the relationship between the two Christian establishments was reasonably complex, after all it would be an overgeneralisation to claim Aksumite subservience to Byzantine. Reflections upon the Chalcedonian-Nicene orthodox dynamics argue for an autonomous Aksum (Rukuni & Oliver 2019), whilst a review of Byzantine Red Sea economic and political policy implies a mutual alliance between Aksum and Byzantium (Cerulli 1959:11, 12; Periplus 4, 5; notes; ed. & trans. Schoff 1912:22-24; 51).

The use of the Alexandrian patriarch was perhaps a reminder to the Christian solidarity between the two nations (Shahid 1976:143). The preceding observation bears significance and can be perceivably substantiated by the imploration through the Holy Trinity by the emperor to the Negus (History of the Wars, I 19-20; ed. & trans. Dewing 1928, 1:178-95). Given the caste between the national orthodoxies that emanated from the theological controversies of Nicaea and Chalcedon, a reminder of what united the Christian brotherhood was a sign of endearment. Justin as the Byzantine emperor was the custodian of the imperial orthodoxy. What the role of arbiter of Christendom implies was reflected in Constantius' attempt to realign Aksumite clergy in conformity with developments in Alexandria (Kobishchanov 1979:67-73). This meant that in relating with Christian nations, Rome was to retain some form of superiority correspondent to its responsibility over all Christendom. However, the attempt to connect to Ethiopian Christianity, which was distinctly divergent from Roman-Byzantine Chalcedonian orthodoxy and essentially Judaised in its practise, was an acknowledgement of the mutual significance of both parties in the alliance. The trinity was an accepted doctrine amongst both nations. As evident in Kaleb's inscriptions, the Son of God and the Holy Spirit were parts of the Godhead closely aligned with all actions carried out by the Negus (Book of the Himyarites; ed. & transl. Moberg 1924). The polemic that defines the derogatory reference to the 'abominable Yusuf' who was to be 'anathema' implies the religious tone that characterised the conflict. Justin was inviting Kaleb as a Christian brother to fight a holy war against the persecutor of Christianity, Masruq.

Mawai Temawe Masqal [victor through the cross], en hoc signos vinces [by this sign conquer]: Victory themes

The battle accounts as read from the martyrology of Arethas played out as war legend. Within the narrative, the port of Adulis posed as a key position as the battle had to be carried to a land across Aksum. Ships assembled at Gabaza near Adulis were to ferry a 120 000 strong cavalry and infantry force (Bowersock 2013:97). The Negus led an armada of 70 vessels to the southwestern region of the Arabian Peninsula (Cosmas Topos, Wolska-Conus 1968-1973, 1:367). The Ethiopian army was to be buffered by a regiment from Barbaria (present-day Somalia) (Bowersock 2013:97). A distinctive feature of the Arabian warfare was the counter-measure they took against the Ethiopian armada. As substantiated by rock inscriptions, one of Yusuf's elementary tactics was blockades to trade routes and ultimately military offences.

The Martyrium recounted that Himyarites had a floating iron chain that was intertwined with wooden planks; this was meant to derail the Ethiopian efforts to reach ashore (Beeston 1989:1-6). The chain narrative is retained in South Arabian inscriptions where the chain is titled as the chain of MDBN; this has led to the conclusion that it was in the region of Maddaban (Nebes 2010:45; Figure 1). This is also backed by the existence of a fortress in the Tihama, at Maddaban (Nebes 2010:51).

The chain narrative is also affirmed by 11th and 13th century CE Arabic sources; in explicit reference, the sources recount how there was an Ethiopian cavalry and infantry assault that was blocked by the Arabs by stretching out a chain on the sea to prevent the former's disembark from their ships. The narrative regarding the chain of MDBN, affirmed as it is, possibly implies an imitation of Persian war etiquette amongst the Arabs. Whilst this assertion borders on supposition, it has to be put into retrospective perspective that Persian-Hellenic warfare was characterised by notable naval sophistication (Hdt Hist 118; Rawlinson 2013:287). Given the resurgence of Persia in the form of the Sassanians and its vivid interests on the Arabian Peninsula, the possibility of this technique being a derivation cannot be ruled out. In spite of the reality of a chain hindrance, Kaleb's Marib, a locale within Southern Arabia (Figure 1) inscription, celebrates how the Negus through divine help managed to make an entrance at the port of Marsa and ultimately defeating Yusuf and destroying the castle at Saba (Gajda 2009:107-108; RIE vol. 1, no. 195, 1991-2000:284-288).

There are political implications of the Marib inscription. Firstly, the positioning of the stele in Himyar and that the inscription was written in Ethiopic or Ge'ez and not Sabaic (Bowersock 2013:100). Apparently, this action connects with the assertive conscious foreign policy of Ethiopia. This redefines the incursion into Arabia as an essentially Ethiopian agenda; this is in spite of the offer by the Romans and the call to arousal by the Byzantine emperor for the Negus to act. Arguably, given the preliminary invasion of Himyar and the entrenchment of the emergent Christian dynasty by the Aksumites, there is a possibility for a substantial fraction amongst the Himyarite population of Ethiopian Christians being resident in the 'client nation as per the Ethiopian claims' (Shahid 1971:iii-iv). Therefore, the war was a rescue effort by the protector of Christianity and also its benefactor Kaleb who also happened to be the Negus over Himyar. Alternatively, the use of Ge'ez was an imperialist endeavour, as Himyar was aggregately under Ethiopian influence. This inscription was meant for all to understand the religious philosophy of the triumphant Negus (King) Kaleb who was magnanimous in comparison to the conquered Yusuf.

The Marib inscription corresponds to the account of Kaleb, which is offered in the Book of the Himyarites, where the Negus is portrayed as giving continuous homilies (Hatke 2011:378-382). Kaleb even in that respect paralleled Constantine's attributed Orations where the monarch's religious ideology is connected to his political and military endeavours (Oratio; ed. Schaff 1855a). For Kaleb, the Old Testament is replete in his declarations and correspondingly his identification with David as exhibited in his name, 'Father of the house of David' Ella Asbeha (ethiopic Esteve & Flores 2006:183). It appears that the representation of Kaleb in respective sources such as the Book of the Himyarites and the Martyrium concurs with his essential biblical typified persona. The emissary of Byzantine to Kaleb, the patriarch of Alexandria, is said to have come in the company of numerable ascetics, and there urged the Negus to go forward, to the aid of the cause of Christianity. This further depicts the assault as one invoked by holy men as the wars of David where he sought counsel from the prophets and Priests (Hatke 2011:378-382).

Bowersock aggregates the Himyarite-Aksumite war of 525 CE as Kaleb's mission for the vengeance of the Najran Christian genocide and guaranteeing the future of Christianity within Arabia (Bowersock 2013:103).

The preceding deduction by Bowersock denotes the war of Kaleb as to have been mainly religious.

In addition, given the retrospective arguments for the equally political nature of the war, it follows that the war was an index of the complex Christian political matrix that characterised the Ethiopian nation. The preceding assertion is in line with Nebes who argues that religious conflict between South Arabian Jews and Christians cannot be a sufficient explanation for the battle for Himyar (Nebes 2010:40).

Kaleb exudes several Constantinian themes when reviewed from the narrative of his Himyarite war. The preceding discussion has focussed on Kaleb as protector of Christianity, that is, by defending Christians against Jewish tyranny. Another reality is Kaleb as the builder and benefactor of Christianity. This can be deduced in different aspects of Kaleb's policy. The first would be Kaleb's connection to the clergy as recounted in the Book of the Himyarites as to how he would work hand in hand with the clerics during his campaign. Explicit examples are Kaleb commanding the baptism of the Himyarite noble and consultation of the Bishop Euprepios regarding the religious state of his cause (Book of the Himyarites XLVII, 54a-b, XLVIII, 55a, ed. & transl. Moberg 1924:140, 141). The second element is the installation of a client Christian monarch to secure the future of Himyarite Christianity.

This is when he installed Sumyafa Ashwa or Esimphaios (the supposed baptised nobleman) (Procopius, Wars 1.20.3; ed. & trans. Dewing 2017:1:32-33). This would be a concrete action, as it guaranteed the security of Christianity as a national religion amongst the Himyarites, thereby joining it to the Ethiopian radius of Christian influence.

When looked at detachedly, Ethiopia was creating its own respective Christendom. In light of the claim by Byzantium to the imperial orthodoxy establishment and the generality of Christendom, an independent Ethiopia was a threat to supremacy, and the sought-out alliance was necessitated by Byzantine's declining power against the backdrop of rising Persian influence.

The last element to Kaleb's benefaction to Christianity was the literal building of churches. When paralleled to Constantine's promotion of Christianity, the actions of Kaleb appear essentially derivative as consequent of his identification with a later timeline. The greater evidence for Kaleb's building policy is derived from a non-verifiable source, St. Gregentius (Fiaccadori 2006:48-82; Shahid 1979:25-94); there is however confirmation of the building efforts of Kaleb in his first invasion of Himyar. Yusuf's documented attacks on Christians had involved converting their churches into synagogues and burning other churches (Shahid 1971:iii-iv). The accounts of Masruq's Christian genocide at Zaphar and the correspondent destruction are attested to in inscriptions (Jamme 1966:39). There is arguable reason to infer that the church destroyed at Zaphar was the one recorded by Philostorgius as to have been built by Theophilus of India in the 4th century CE (Philostorgius HE Book 3.4; Amidon 1997:40). The preceding observation further affirms how the Negus' policy in Himyar was one of supporting an already established Christianity that was challenged by resurgent persecuting Judaic powers. Therefore, the 6th century CE Ethiopian cathedral at Zaphar was a restoration of a once demolished building. There are other church buildings that although not verifiable are attributed to Kaleb in the life of St. Gregentius (Bowersock 2013:104; Fiaccadori 2006).

After his victory, Kaleb remained a significant ally of Byzantine Rome as confirmed by the visit of Nonnosus as the ambassador to Aksum. The imperial establishment that ensured a client Himyar did not transcend his reign and retirement3 it would seem, as there were transformative dynamics in Himyar that ultimately saw the resurgence of the Sassanians and subsequently the rise of Islam (Donner 2010:125). However, it is the persona of Kaleb that stands out as a significant feature of the narrative behind the religious war of Himyar and Aksum.

The Negus arguably encapsulates the Constantinian themes. As defender and benefactor of Christianity and a successful general, Kaleb maintained the continuum identifying the golden age of Aksumite's magnanimity and its Christianisation. Parallel to Ezana, Kaleb stands out as the protector and promoter of the faith that had taken hold of a nation. Kaleb balanced the ecclesiastical-imperial implications of a Christian-political matrix.

From the perspective of the deductive nature of Ethiopianism as a metamorphosis of Ethiopian narratives into commentative insights, the persona of Kaleb remains a definitive figure symbolising the merger of piety and power, politics and religion. This, when viewed with respect to the parallels that are deductible between Kaleb and Constantine, establishes a connection between Constantinianism and Ethiopianism.

Constantinianism and Ethiopianism themes

There is a portrait titled The Image of the Black, which is:

Full-length standing portrait of St. Elesbaan, emperor of Abyssinia, holding the Church in one hand and a spear in the other with which he has slain evil. (W.E.B. Du Bois Institute 2019)

This portrait is an 18th century CE Portuguese depiction of Kaleb, a celebrated Ethiopian legend (The Book of the Saints 1.117, Budge 1928:289-293). There are significant elements that are portrayed in the image that relate to the discussion regarding the Constantinian themes replete in the narratives of Kaleb.

A thematic title for the portrait would be piety and power. Kaleb is here portrayed as both cleric or ascetic and monarch, as seen in his robes that fit either categories and the monk's tonsure. His crown is at the bottom of his feet, a possible reference to how he relinquished his reign for him to retire to ascetism (in the donation of his crown) (Cerulli 1943-47; Meinardus 1965). The preceding notion is debated by the very authors who mention its factuality; however, one arguable reality is the affinity between monarchical and the ecclesiastical establishment, the Abuna and Negus of Ethiopia have always shared an important relationship. The above-mentioned notion is decoded as a later phenomenon characterising Ethiopian Christianity in the medieval era, or rather as some have chosen to designate it as the formation of Ethiopian Feudalism (Binns 2017:40-44; Isaac 2013:131; Negash 2018:1-4; Tamrat 1972).

In both hands, the Negus holds symbols of piety and power. Whilst on the one hand, Kaleb holds an elongated spear and dually a standard, on the other hand, he bears a cathedral. Regarding the spear, the militarism of Kaleb defined his foreign policy with Himyar. In addition, it should be remembered that Ethiopia from Ezana and his predecessors embarked on a regional expansion policy (cf. Bowersock 2013). These were imperialist ambitions; the Negus was not just a (king) Negus, but the (king of kings) Nagashi (Altheim & Stiehl 1961: 234-248; Jamme 1966:39). In addition, the standard embellishes a sign that is also suggestive, a lion like figure holding a cross.

Given the derivate biblical connotations that characterise Kaleb's inscriptions and his Ge'ez name Ella Asbeha, that implies his posture as a Davidic figure who is akin to the Son of God, deductively this represents the Lion of the tribe of Judah motif. In his inscriptions as reviewed, the Marib and Aksumite inscription, Kaleb impressed both New and Old Testament upon his commemorative stele (Jamme 1966). The intrinsic biblical nature of the claims made within the stele reaffirm the notion of Kaleb having his own 'Oratio' that corresponds to Constantine's homilies as decoded by Eusebius (Oratio; ed. Schaff 1855a:880). Hence, this observation coupled with the distinct Judaic nature of Ethiopian Christianity, which can be aggregated to be divergent from elements in Eastern (Syriac) Christianity, would imply a biblical source for the Negus' claims as more appropriate than otherwise. This can be said regarding the notion of the Negus being king of kings, whilst certain scholarship would parallel this to Persian claims (Procopius Wars Book 1.14; ed. & trans. Dewing 2017:1:21). There is a case for the biblical tradition as source.

The Lion of the tribe of Judah is a notion that is traceable to the Bible where the figure of a lion is symbolic of victory and majesty (Gn 49:9; Nm 23:24; 24:9; 1 Macc 3:4; Rv 9:17) (Wolcott 2016). The identity of the Negus as Lion of Judah is replete in Ethiopic literary sources (Haile & Macomber 1981). Notably in the Bible, these titles are ascribed to Christ, the second person of the Godhead, who was mentioned extensively in Ethiopian royal inscriptions and upon coins (RIE I-III: 1991-2000). The fact that the lion holds a cross is an explicit argument to this effect. This would also correspond to the apocalyptic Book of Revelation where Jesus is denoted as Lion of Judah and the root of David (Rev 5), and king of kings (Rv 19:10).

This shows how the king essentially drew some parallel representation to the person of deity in the form of the Son of God (a prevalent Constantinian etiquette that defined the sole emperorship (Schott 2008)). Some of the references to the Lion of Judah come to define the Negus complex later and extendedly the derived religion of Rastafarianism (Erskine 2005:47). When the illustrated ideology is positioned within the reality of the Negus' claims as evidenced by the epigraphic and archaeological evidence, the notion that Ethiopia was defined by a complex church-state liaison can be argued as an understatement. What can be said of the 'holy Byzantine-Roman empire', is equally justified for the conceptualisation of a 'holy Ethiopian kingdom'. The parallelism between the Negus and Constantinan institution is arguably explicit; it should be noted that it is a review of these respective parallels that enhances the conceptualisation of the past (cf. Haas 2008). The artist's impression of the standard on the same spear piercing the Himyarite king is derivative, Kaleb emphasises that his victory was granted him by Divine assistance by the Son of God, as evidenced in the Marib inscription (Jamme 1966).

The standard is the one triumphant over the persecutor of Christians, Masruq; it is the cross that was victorious (Book of the Himyarites; ed. & transl. Moberg 1924). This emphasises the Mawai, temawe Masqal theme, conqueror through the cross that seemingly becomes deduced as a derivative in the perspective of centuries earlier in 300s CE where Constantine embellished the en hoc signes vincis [the invincible cross] (Lenski 2006:71; cf. DMP 44.5-6; Phillipson 2012:189; ed. Schaff 1885b:486-487). Both Constantine and Kaleb can be identified for their explicitly Christian martial policy.

The other feature, which has been discussed earlier, is the element of the custodian of Christianity. Kaleb with his other hand holds a cathedral. The benefactor of Christianity policy has been identified within the Negus' actions. The driving factor behind the Himyarite war was the protection of Christians from gruesome persecution at the hands of Yusuf or Masruq as designated by the Book of the Himyarites. This theme can be observed from a completely Constantinian-derivate theme where the actions of the Negus can be reviewed in the shadow of Constantine's similar efforts. Rather, it would be insightful to intrinsically review the Negus' policy detachedly and then deduce the parallelisms as this would entail reading the narrative from an Ethiopian viewpoint.

Firstly, the Negus' 518 CE invasion of Himyar has been decoded as an endeavour to aid a waning Christian establishment that was threatened by an assertive Jewish presence. After which the Negus Kaleb reinforced the ecclesiastical establishment and installed a client monarch, Sumyafa Ashwa or Esimphaios. The 525 CE war was similarly consequent of Jewish persecution of Christianity by the Judaic Himyarite monarch; to prevent further Christian genocide and destruction of churches, the Negus had to intervene as protector of Christianity.

As already reviewed, the narratives as recounted in the Book of the Himyarites, the emperor pursued his advances in consort with the clergy. The Negus was involved even in the repentance of compromising Christians and his actions denote him as a clerical-political agent.

The restoration of the cathedral at Zaphar and the building of the Aksumite cathedral were explicit overtures in support of Christianity. This can be decoded as not unusual against the backdrop of medieval Frankish, Russian Christianity where feudalism guaranteed the reality of monarchs building and dedicating cathedrals (cf. Kitromilides 2006:229-250; Moore 2011:244-246); this was however centuries before the rise of a medieval Christendom with monarchical ties. Kaleb's actions when viewed within the composite Negus Christian policy post-Ezana point to a notable Christian political establishment that parallels Constantine. The Vandals, another temporary African regional power, had aggregately maintained what had been Roman; the Ethiopians however were a distinctly new player in the arena of Christian domestic and foreign policy. The picture shows the cathedral drawn close to Kaleb's chest, a depiction of how the cause of Christianity was an endeared part of the Negus' policy. The martial offences of the Negus were for the defence of Christianity.

The spear piercing the Himyarite king on the other hand was the martial policy, whereas the cathedral on the other side was the benefactor element of Christian policy.

Lastly, the one foot upon the lying body of a crowned Masruq that accompanies the spear on his neck implies complete victory. More especially an ideological victory that corresponds to the Negus' emphasis that it was a victory of the cross that would be gained by triumphing over the Himyarites. Whereas Kaleb would be willing to lay off his crown and be rather an ascetic, the 'proud' Himyarite Masruq would be conquered in his majesty by the 'meek' Kaleb, who in this case has become the instrument of divine justice. The military triumphalism that characterises the portrait ever defined Ethiopia as it would seem. The attitude that places akinness between militant triumphalism and piety, further entrenched within the Ethiopian religious political psyche, characterised intrinsic Ethiopian narratives and extendedly the derivate concepts of Ethiopianism and Rastafarianism.

Positioning a Constantinian Kaleb within the Kebra Naghast: Conclusion

The focus on Kaleb enhances the perception regarding ancient Ethiopian church-state relations. The reality of a monarchical-ecclesiastical establishment defines in essence the Christian narrative of Ethiopia; Ezana stands out as the first Christian monarch, whilst Kaleb stands out for his external geopolitical Christian policy (Kaplan 1982; Shahid 1976). However, whilst the preceding deductions have received aggregate attention and focus, it seems the dynamic of ecclesiastical-imperial politics has been perceived as to have been a significant feature later during medieval Ethiopia (Binns 2017:40-44; Tamrat 1972). This perhaps being confirmed by the emergence of the Zagwe dynasty as a highly religious-political entity in 1270 CE. Even the Kebra Naghast, the record of the religious-political heritage of Ethiopia was assigned to the Ethiopian medieval era (Piovanelli 2014).

The focus on Kaleb in diversified angles as an index of the Ethiopian early Christian religious-political terrain develops substantial theorem. As a parallel justification, it has to be put into retrospect that despite the entrenchment of the episcopal polity in the medieval era and their corresponding absorption into the feudal establishment, the emergence of an imperial-episcopal Christian phenomenon in the 300 CE remains a key feature in decoding the development of church-state relations. It is an explicit notion that Constantinian momentum is a referral code for religion and governance to this day (Long 2013:100-124). Therefore, the 3rd - 6th century CE when there were significant dynamics that redefined imperial and ecclesiastic establishments in both Rome-Byzantine and Ethiopia thereby derives significance as the foundational era to the emergence of a functional feudal system. Moreover, the capacity of the involved monarchs to integrate Christianity within their foreign policy and statecraft is a notable element definitive of this era.

The Kebra Naghast, which as implied in its name is the glory of the kings, shows the intrinsic sensation that defined the narrative of Ethiopian power dynamics. The monarchy of Ethiopia was part of the legend that shaped a national religious identity. Positioning Kaleb within this matrix would be appropriate. It has to be established that there are elements of credibility with the Kebra Naghast that suggests it was more of a derivate document resembling the medieval era's projection of Ethiopian splendour. In other words, the Kebra Naghast essentially becomes a composition of excerpts from earlier sources that was establishing the national orthodox religious propaganda. This theory has been posed by Piovanelli, basing upon the eclipse of Aksumite eminence between Kaleb and the 12th century CE phenomenon of the Zagwe dynasty (Phillipson 2012:227-243; Piovanelli 2014:690). Thereby, the Kebra Naghast was an attempt by the clerical establishment of Ethiopia to compose a narrative of Christian orthodoxy and political dominance. However, there is a hint for a later 7th century CE dating that is proposed by Bowersock, Shahid; the respective view derives from the prominence of Kaleb and the Himyarite war (Bowersock 2010; Shahid 1971, 1976). Emphatically, Kaleb and the Himyarite war are attestable through epigraphic and archaeological data. Therefore, there should be room for a record that was close to the eventualities.

It has to be noted that the Kebra Naghast account of the massacres of Najran, and the ensuing battle between Kaleb and Yusuf/Masruq/Finḥas, is derived from an Ethiopic version of the Martyrium of Arethas (Bausi & Gori 2006:106). This narrative that has been morphed into legend corresponds to the international relevance of Ethiopia poised by the authors of the Kebra Naghast. The significance assigned to Kaleb is distinctive; he is the conclusion, the ultimate exhibit of the thesis (Kebra Naghast Ch. 117; Budge 2000:197). The parallel nature of the Kebra Naghast to the Book of the Himyarites, Pseudo Methodius, is also implicative; there is an agenda of the international eschatological projection of a religious empire (Minski 2016:1-7; Piovanelli 2013:13; Shahid 1976:135). It has to be placed into perspective as to how Kaleb is positioned within the Kebra Naghast. In a deductive sense, there is an emphatic claim to superior religious statecraft as a defining characteristic of Ethiopia. The preceding would have been efficient propaganda fuel for the medieval Ethiopian dynasty dynamics and extendedly to maintain the aura of a divine monarchy.

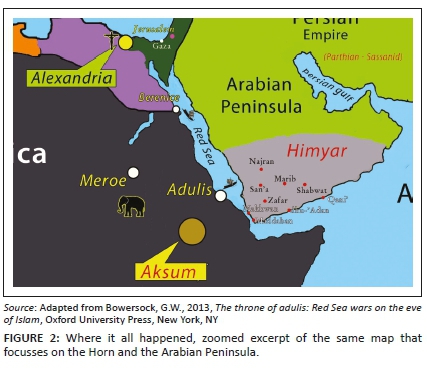

Figure 2 is a zoomed excerpt of the same map that focusses on the Horn and the Arabian Peninsula.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exist.

Author's contributions

I declare that I am the sole author of this research article.

Ethical consideration

This article followed all ethical standards for a research without direct contact with human or animal subjects.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the author.

References

Al-Assouad, M.R., 2019, 'Dhu Nuwas', in K. Fleet, G. Kramer, D. Matringe, J. Nawas & E. Rowson (eds.), Encyclopedia of Islam, 2nd edn., Brill Online, Leiden. [ Links ]

Ali, M.S. (trans.), 1955-2015, The Holy Quran with English translation, Islam International Publications Ltd., Surrey. [ Links ]

Allen, P., 2001, 'The definition and enforcement of Orthodoxy', in A. Cameron, B. Ward-Perkins & M. Whitby (eds.), Cambridge ancient history, vol. 14, pp. 811-835, Cambridge University Press, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Altheim, F. & Stiehl, R., 1961, 'Die Datierung des Konigs 'Ezana von Aksum,' Klio, 39, 234-248. [ Links ]

Amidon, P.R., 1997, The Church History of Rufinus of Aquileia, books 10 & 11, Oxford University Press, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Baron, S.W., 1957, A social and religious History of the Jews, Columbia University, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Bausi, A. & Gori, A., 2006, Tradizioni orientali del 'Martirio di Areta', La prima recen sione araba e la versione etiopica, Edizione critica e traduzione, Università di Firenze, Florence. [ Links ]

Beaucamp, J., Briquel-Chatonnet, F. & Robin, C.-J. 1999, 'La perskcution des chretiens de Nagrän et la chronologie Himyarite', ARAM 11-12, 15-83. https://doi.org/10.2143/ARAM.11.1.504451 [ Links ]

Beeston, A.F.L., 1989 'The chain of Mandab', in On both sides of al Mandab. Ethiopian, South Arabic and Islamic studies presented to Oscar Lofgren on His 90th birthday, pp. 1-6, Swedish Research Institute in Istanbul, Stockholm. [ Links ]

Beeston, A.F.L., 2005, 'The Martyrdom of Azqir', Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies 16(1985), 5-10, reprinted in Beeston, A.F.L., at The Arabian seminar and other papers, M.C.A. Mcdonald & C.S. Philips (eds.), pp. 113-118, Archaeopress, Oxford. [ Links ]

Berger, A. (ed.), 2012, 'Life and works of Saint Gregentios, Archbishop of Taphar: Introduction, critical edition and translation', in Millennium-Studien/Millennium Studies, vol. 7, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin. [ Links ]

Berti, M., 2019, 'Nonnosi Fragmenta 1.P. 179 Photius Bibl. Cod. 3', in Digital Fragmenta Historicorum Graecorum, Universitat Leipzig, Leipzig, a digitalised version of K. Muller (ed.), 1841-1872, Fragmenta Historicorum Graecorum (FHG), Ambroise Firmin-Didot, Paris, viewed 08 September 2019, from http://www.dfhg-project.org/DFHG/search.php?what=Nonnosus. [ Links ]

Bidez, J. & Parmentier, L. (eds.), 1898, The ecclesiastical history of Evagrius with the Scholia, Methuen & Co, London. [ Links ]

Binns, J., 2017, The orthodox church of Ethiopia: A history account, I.B. Tauris, London. [ Links ]

Bosworth, C.E., 1983, 'Iran and the Arabs before Islam', in W.B. Fisher & E. Yarshater (eds.), Cambridge history of Iran volume 3, pp. 593-613, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Bowen, G.A., 2009, 'Document analysis as a qualitative research method, Qualitative Research Journal 9, 27-40. https://doi.org/10.3316/QRJ0902027 [ Links ]

Bowersock, G.W., 2010, 'Helena's Bridle, Ethiopian Christianity, and Syriac Apocalyptic', in J. Baun, A. Cameron, M. Edwards & M. Vincent (eds.), Studia Patristica: Papers presented at the Fifteenth International Conference on Patristic Studies, pp. 211-220, Peeters Publishers, Louvain. [ Links ]

Bowersock, G.W., 2012, '"Nonnosus and Byzantine diplomacy in Arabia", for the Festschrift in honor of Emilio Gabba', Rivista Storica Italiana 124, 282-290. [ Links ]

Bowersock, G.W., 2013, The throne of Adulis: Red Sea Wars on the eve of Islam, Oxford University Press, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Brooks, E.W. (ed.), 1923, Lives of the Eastern Saints: Patrologia Orientalis 17, fasc 1, pp. 137-158, Societas Jesu, Rome. [ Links ]

Budge, E.A.W., 1928, The book of the Saints of the Ethiopian Church, 4 vols, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Budge, E.A.W., 2000, The Queen of Sheba and Her Only Son Menyelek: Kebra Nagast, Ethiopian Series Cambridge Publications, ON. [ Links ]

Cameron, A. & Hall, S.G., 1999, 'Eusebius: Life of Constantine l', in B. Bosworth, M. Grin, D. Whitehead & S. Treggiari (eds.), Clarendon ancient history series, University Press Inc., New York, NY. [ Links ]

Cerulli, E., 1943-1947, Etiopi in Palestina: Storia della comunità etiopica in Gerusalemm, 2 vols, Libreria dello Stato and Topografia Pio X, Rome. [ Links ]

Cerulli, E., 1959, 'Perspectives on the history of Ethiopia' (Punti di vista sulla storia dell'Etiopia'), in Atti del Convegno Internazionale di Studi Etiopici, Roma, Problemi attuali di scienza e di cultura 48, pp. 5-28, Papaconstantinou, A. (trans.), 2012, Ashgate Publishing Ltd, republished in Bausi, A. (ed.), 2012, Languages and cultures of Eastern Christianity: Ethiopian, pp. 1-25, Ashgate Publishing Ltd., Surrey. [ Links ]

Danto, E.A., 2008, Historical research, Oxford Scholarship Online, viewed 12 January 2018, from http://www.oxfordscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195333060.001.0001/acprof-9780195333060. [ Links ]

Dewing, H.B. (ed. & trans.), 1914-1928, Procopius: History of the wars, Heinemann, Loeb Classical Library, London. [ Links ]

Dewing, H.B. (ed. & trans.), 1914-1928, 2017, Procopius: History of the wars, Heinemann, Loeb Classical Library, London taken from Wikisource: History of the Wars/Book 1-8. (2017, May 3)', Wikisource, viewed 06 November 2018, from https://en.wikisource.org/w/index.php?title=History_of_the_Wars/Book_I&oldid=6790552. [ Links ]

Dillman, A., 1865, Lexicon Linguae Aethiopicae, T.O. Weigel, Leipzig. [ Links ]

Donner, F., 2010, Muhammad and the believers: At the origins of Islam, Harvad University Press, Cambridge, MA. [ Links ]

Erskine, N.L., 2005, From Garvey to Marley: Rastafari Theology, University Press of Florida, Gainesville, FL. [ Links ]

Esteve, F.J.G. & Flores, D.C., 2006, Touching Ethiopia, Shama Books, Addis Ababa. [ Links ]

Ferguson, T.C., 2005, 'The past is prologue: The revolution of Nicene Historiography', in J. Den Boeft, J. Van Oort, W.L. Petersen, D.T. Runia, C. Scolten & J.C.M. Van Winden (eds.), Supplements to Vigilae Christianae (Formely Philosophia Patrum) texts and studies of Early Christian life and language, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Fiaccadori, G., 2006, 'Gregentios in the Land of the Homerites', in A. Berger (ed.), Life and works of Saint Gregentios, Archbishop of Taphar, pp. 48-82, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin. [ Links ]

Fowden, E.K., 2006, 'Constantine and the Peoples of the Eastern Frontier', in N. Lenski (ed.), The Cambridge companion to the age of Constantine, pp. 377-398, Cambridge University Press, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Gajda, I., 2009, Le royaume de Himyar a lepoque monotheiste: L'histoire de l'Arabie du sud ancienne de la fin du IVe siècle, AIBL & De Boccard, Paris. [ Links ]

Haas, C., 2008, 'Mountain Constantines: The Christianization of Aksum and Iberia', Journal of Late Antiquity 1.1 (Spring), 101-126. https://doi.org/10.1353/jla.0.0010 [ Links ]

Haile, G. & Macomber, W.F., 1981, A Catalogue of Ethiopian manuscripts microfilmed for the Ethiopian Manuscript Microfilm library, Addis Ababa and for the Hill Monastic Manuscript Library, Collegeville V. Project Numbers 1501-2000, Collegeville, MN. [ Links ]

Haldon, J., 2011, The Byzantium at War AD 600-1453, Routledge-Taylor and Francis, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Hatke, G., 2011, 'Africans in Arabia Felix: Axumite Relations with Himyar in the Sixth Century C.E.', Ph.D. dissertation, Princeton, NJ. [ Links ]

Hendrickx, B., 2012, 'Political theory and Ideology in the Kebra Nagast: Old Testament Judaism, Roman-Byzantine Politics and Ethiopian Orthodoxy', Journal of Early Christian History 2(2), 22-35. https://doi.org/10.1080/2222582X.2012.11877263. [ Links ]

Hendrickx, B., 2017, 'Letter of Constantius II to Ezana and Sezana: A note on its purpose, range and impact in an Afro-Byzantine context', Graeco-Arabica 12, 545-556. [ Links ]

Insoll, T., 2004, Archaeology, ritual, religion, Routledge, London. [ Links ]

Isaac, E., 2013, The Ethiopian Orthodox Tawahido Church, The Red Sea Press, Trenton, NJ. [ Links ]

Jamme, A., 1966, 'Sabaean and Hasaen inscriptions from Saudi Arabia', Studi Semitici 23. [ Links ]

Jeffreys, E. (trans.), 1986, The chronicle of John Malalas, Byzantina Australiensia 4, Australian Association for Byzantine Studies, Melbourne. [ Links ]

Kaplan, S., 1982, 'Ezana's conversion reconsidered', Journal of Religion in Africa 13, 101-109, republished in Bausi, A. (ed.), 2012, Languages and cultures of Eastern Christianity: Ethiopian, pp. 27-55, Ashgate Publishing Ltd., Surrey. [ Links ]

Kister, 1968, 'Al-Hira: Some notes on its relations with Arabia', Arabica 15, 143-169. https://doi.org/10.1163/157005868X00190 [ Links ]

Kitromilides, P.K., 2006, 'The legacy of the French Revolution: Orthodoxy and nationalism', in M. Angold (ed.), Vol. 5: Christianity: Easter Christianity, pp. 229-250, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Kobishchanov, Y.M., 1979, Axum, transl. L.T. Kapitanoff (from Russian), pp. 67-73, The Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park, TX. [ Links ]

Lee, A.D., 2006a, 'The empire at war', in M. Maas (ed.), The Cambridge companion to the age of Justinian, pp. 113-133, Cambridge University Press, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Lee, A.D., 2006b, 'Traditional religions', in N. Lenski (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine, pp. 159-180, Cambridge University Press, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Leithart, P.J., 2010, Defending Constantine: The twilight of an Empire and the Dawn of Christendom, Inter-Varsity Press, Downers Grove, IL. [ Links ]

Lenski, N., 2006, 'The reign of Constantine', in N. Lenski (ed.), The Cambridge companion to the age of Constantine, pp. 59-90, Cambridge University Press, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Long, D.S., 2013, 'Yoderian Constantinianism', in J.D. Roth (ed.), Constantine revisited: Leithart, Yoder, and the Constantinian debate, pp. 100-124, Pickwick Publications, Eugene, OR. [ Links ]

Martindale, J.R., 1992, The Prosopography of the Roman Empire 2 Part Set: Volume 3, AD 527-641, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Meinardus, O.F.A., 1965, 'The Ethiopians in Jerusalem', Zeitschrift für Kirchengeschichte ser 4(14), 117-47, 217-232. [ Links ]

Minski, M.L., 2016, The Kebra Nagast and the Syriac Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius: A Miaphysite Eschatological Tradition, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Faculty of Humanities Department of Comparative Religion, Jerusalem. [ Links ]

Moberg, A. (ed. & transl.), 1924, The Book of the Himyarites, vol. 7, Acta regiae Societatis humaniorum litterarum Lundensis, Lund. [ Links ]

Moore, M.E., 2011, A sacred kingdom: Bishops and the rise of Frankish Kingship, 300-850, vol. 8, The Catholic University of America Press, Washington, DC. [ Links ]

Nebes, N., 2010, 'The Martyrs of Najran and the end of Himyar: On the political history of South Arabia in the early sixth century', in A. Neuwirth, N. Sinai & M. Max (eds.), The Qur'an in Context Historical and Literary Investigations into the Quranic Milieu, pp. 27-59, Leiden. [ Links ]

Negash, T., 2018, The Zagwe period re-interpreted: Post-Aksumite Ethiopian urban culture, Uppsala University, Uppsala. [ Links ]

Phillipson, D.W., 2012, Foundations of an African civilisation: Aksum & the Northern Horn 1000 BC-AD 1300, James Currey, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Piovanelli, P., 2013, 'The apocryphal legitimation of a "Solomonic" dynasty in the Kǝbrä nägäśt - A reappraisal', in A. Bausi, B. Tafla, U. Braukämper, L. Gerhardt, H. Meyer-Bahlburg & U. Siegbert (eds.), Aethiopica 16, International Journal of Ethiopian and Eritrean Studies 7-44, der Universität Hamburg, Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden. [ Links ]

Piovanelli, P., 2014, '"Orthodox" faith and political legitimization of a "Solomonic" dynasty of rulers in the Ethiopic Kebra Nagast', in K.B. Bardakjian & S. La Porta (eds.), The Armenian Apocalyptic tradition: A comparative perspective essays presented in honor of Professor Robert W. Thomson on the Occasion of His Eightieth Birthday, pp. 688-705, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Pohl, W. (ed.), 1997, Kingdoms of the Empire: The integration of Barbarians in Late Antiquity, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Rawlinson, G., 2013, 'Herodotus: The histories', in Western culture: A Christian approach to the great book, Roman Roads Media, ID. [ Links ]

RIE I-III, Bernand, E., Drewes, A.J. & Schneider, R., 1991-2000, Recueil des Inscriptions de I'Ethiopie des periodes preaxoumite et axoumite, introduction by Fr. Anfray, 3 vols, Vol 1, Les documents, Vol. 2, Lesplanches, Vol. 3, Traductions et commentaires A. Les inscriptions grecques par E. Bernand, Paris. [ Links ]

Ritchie, J. & Lewis, J., 2003, Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers, Sage, London. [ Links ]

Robin, C.J., 2004, Himyar et Israel, Academie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, Comptes, Rendus des seances de l'annee 2004 [published 2006, avril-juin], pp. 831-906, Paris. [ Links ]

Robin, C.J., 2009, 'Les Arabes de Himyar, "des Romains" et des Perses (III-VI siecles de lere chretienne)', Semitica et Classica I(2008), 167-202. https://doi.org/10.1484/J.SEC.1.100252 [ Links ]

Robin, C.J. & De Maigret, A., 2009, 'Le royaume sudarabique de Ma'in: Nouvelles données grâce aux fouilles italiennes de Barâqish (l'antique Yathill)', Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 2008, 57-96. https://doi.org/10.3406/crai.2009.92443 [ Links ]

Rukuni, R., 2018, The schism, Hellenism and politics: A review of the emergence of ecumenical orthodoxy AD 100-400, University of South Africa, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Rukuni, R. & Oliver, E., 2019, 'African Ethiopia and Byzantine imperial orthodoxy: Politically influenced self-definition of Christianity', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 75(4), a5314. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v75i4.5314 [ Links ]

Schaff, P. (ed.), 1885a, 'Nicene and post-Nicene fathers', series 2, vol. 1: Eusebius Pamphilius: Church history, life of Constantine, oration in praise of Constantine, Christian Classics Ethereal Library, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Schaff, P. (ed.). 1885b, 'Ante-Nicene Fathers', vol. 7: The fathers of the third and fourth centuries, Christian Classics Ethereal Library, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Schaff, P. (ed.), 1885c, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Series 2, Vol. 1: Eusebius Pamphilius: Church history, life of Constantine, oration in praise of Constantine, Christian Classics Ethereal Library, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Schoff, W.H. (ed. & trans.), 1912, Periplus Maris Erythraei (The Periplus of the Erythraen Sea: Travel and trade in the Indian Ocean), Longmans, Green, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Schott, J.M., 2008, Christianity, empire, and the making of religion in late antiquity, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, PA. [ Links ]

Shahid, I., 1971, The Martyrs of Najran: New documents, Imprimerie Cultura, Wetteren. [ Links ]

Shahid, I., 1976, 'The Kebra Naghast in the light of recent research', Le Museon 89(1976), 133-178, Editions Peeters, Louvain republished in Bausi, A. (ed.), 2012, Languages and cultures of Eastern Christianity: Ethiopian, pp. 253-298, Ashgate Publishing Ltd., Surrey. [ Links ]

Shahid, I., 1979, 'Byzantium in South Arabia', pp. 25-94, Dumbarton Oaks Papers 33, Washington, DC. [ Links ]

Shahid, I., 1989, Byzantium and the Arabs in the fifth century, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, DC. [ Links ]

Shahid, I., 1995-2002, Byzantium and the Arabs in the sixth century, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, DC. [ Links ]

Tamrat, T., 1972, Church and state in Ethiopia, 1270-1527, Clarendon Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

The Image of the Black, in Western Art Research Project and Photo Archive, W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for African and African American Research, Harvard University, viewed 16 July 2019, from www.artstor.org. [ Links ]

Ure, P.N., 1951, Justinian and his age, Penguin Books, Harmondsworth. [ Links ]

Whelan, R., 2018, Being Christian in Vandal Africa: The politics of orthodoxy in the Post-Imperial West, University of California Press, Oakland, CA. [ Links ]

Wolcott, C.S., 2016, 'Lion', in J.D. Barry, D. Bomar, D.R. Brown, R. Klippenstein, D. Mangum, C. Sinclair, et al. (eds.), The Lexham Bible Dictionary, Lexham Press, Bellingham, WA. [ Links ]

Wolska-Conus, W., 1968-1973, Cosmas Indicopleustès: Topographie Chrétienne (3 vols), Editions du Cerf (Sources chrétiennes 141, 159, 197), Paris. [ Links ]

Wright, W., 1882, The chronicle of Joshua the Stylite, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Yamauchi, E.M., 1972, The stones and the scriptures, Holman, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Rugare Rukuni

rugareeusebius@gmail.com

Received: 13 Nov. 2019

Accepted: 09 Mar. 2020

Published: 09 Oct. 2020

1 . Ezana (reign 320s - c. 360s CE) is recorded as the first Christian monarch of Aksumite Ethiopia, whereas Kaleb (6th century CE) was notable for an extensive Aksumite Christian foreign policy, particularly in Himyar.

2 . Frumentius (4th century CE) is the known first Bishop of Aksum (appointed by the Alexandrian patriarch Athanasius), who initially was a Syrian Christian who through legend-like circumstances found himself in the Aksumite court.

3 . Kaleb retired into the seclusion of monasticism.