Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

HTS Theological Studies

On-line version ISSN 2072-8050

Print version ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.76 n.4 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v76i4.5835

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Church history is dead, long live historical theology!

Peter Houston

Department of Systematic Theology and Ecclesiology, Faculty of Theology, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Church history is dead, long live historical theology! This restatement of the monarchical law of le mort saisit le vif is at once a statement of irreparable discontinuity and assumed continuity. The old monarch is no more, yet a new and different monarch ascends to fill the same vacant throne. This is the paradox of church history becoming historical theology. Reviewing the work of W.A Dreyer and J. Pillay on the re-imagining of church history as historical theology, this article explores the tension between the demise of church history as a subject in South Africa and the emerging understanding and application of historical theology, arguing that more can be made of trans-disciplinary dialogues.

Keywords: church history; environmental theology; historical theology; South African universities; theological disciplines; transdisciplinary.

Introduction

Church history is dead. At least this is the case in South African universities. Church history has come to be perceived as an irrelevant and marginalised discipline. There are several notable reasons for this. Firstly, church historians were regarded with suspicion because of a lack of critical engagement during apartheid (Dreyer 2017).

Many preferred to listen to the voices which gave theological, philosophical and theoretical justification to ethnic nationalism (Dreyer 2017). Secondly, church history became almost completely cut off from social sciences and from secular history resulting in a weakening of its academic status within the university academy (Denis 1997).

The subject was taught by theologians with little or no training in secular history approaches (Denis 1997). Thirdly, church historians tended to place more emphasis on the theological and ecclesiastical identity of their denominations, with the justifying of past actions taking precedence over historical criticism (Dreyer 2017).

Fourthly, there has been a radical shift in South Africa away from simply considering the terms of the transposition of certain denominational forms of the Christian faith from Europe to Africa but rather in terms of the contextual experience of African peoples (Ross 1997). Fifthly, post-1994, several theological faculties have been closed or restructured to form part of the faculties of Arts or Humanities. Theology itself, never mind church history, is low on the list of tertiary institutions' funding concerns so Theology itself is under pressure (Dreyer & Pillay 2017). Sixthly, there is a general lack of interest in South Africa in History as a subject, never mind church history more specifically (Dreyer & Pillay 2017).

For any number of these reasons, a distancing from church history has been observed in most theological faculties or schools of religion in South Africa. In 1992, the University of KwaZulu-Natal abandoned the designation church history in favour of the 'History of Christianity' (Denis 1997). The University of Fort Hare (UFH) and the Western Cape also teaches History of Christianity. The Universities of Stellenbosch, North West and the Free State have all adopted the term 'Ecclesiology' (Dreyer 2017). In 2017, a decision was subsequently taken at UFH that the Departments of Systematic Theology and Ecclesiology would merge to become the Department of 'Historical and Constructive Theology' (Bloemfontein Courant, 03 September 2017). This represents a further shift. An outlier in this trend is the University of South Africa, where church history has been subsumed into a single Department of Christian Spirituality, Church History and Missiology. The official merger of the three disciplines happened towards the end of 2005.1 Moreover, theological disciplines have been subsumed under Religious Studies at other South African universities or simply do not exist. Church History is dead; long live historical theology.

The rise of historical theology

Out of the shell of church history has arisen the language and discourse of historical theology that owes its origins to church history but is not limited to church history. The new monarch ascended to the throne is distinctly different. The ascendance of historical theology has not been straightforward, given that there are some significant, but surprisingly few, proponents of historical theology as a separate theological discipline.

Dreyer (2017) lists just three theologians who have helped to define historical theology - Ebeling, Bromiley and McGrath, with a fourth - Pannenberg - adding to the narrative. Dreyer and Pillay (2017) contribute a further three theologians - Heidegger, Bultmann, Barth - to the discussion.

German Lutheran theologian, Gerhard Ebeling, began using the term 'historical theology' in the late 1940s, applying it to biblical interpretation. His primary concern was with how various theologians throughout history went about their business of interpreting the Bible (Dreyer 2017).

In 1978, American theologian, Geoffrey W. Bromiley, published what is today still one of the defining works on historical theology and it went by that same name. He defined the general work of Theology as the:

[I]nvestigation of the church's word about God with the intent of testing and achieving its purity and faithfulness as the responsive transmission of God's Word in changing languages, vocabularies, and intellectual and cultural contexts. (Bromiley 1978:113)

historical theology was, for Bromiley, not just a history of Christian theology but was in itself, theology (Bromiley 1978). However, even as he sought to define historical theology, he asserted that 'an ideal historical theology lies beyond the limits of human possibility. Indeed, even the 'ideas of the ideal differ so broadly that what might approximate the ideal for some falls hopelessly short for others' (Bromiley 1978).

Bromiley thought, at best, that 'historical theology fills the gap between the time of God's Word and the present time of the church's word by studying the church's word in the intervening periods' (Bromiley 1978). An important aspect of his work was to develop a framework for a historical theology methodology, which constitutes five approaches (Bromiley 1978):

1. Rapid survey, 'which attempts a sketch of everybody and everything'.

2. Detailed and multi-volumed study, 'which tries to say everything about everybody and everything'.

3. Interpretative theses, 'which advance a series of interesting theories or theses according to which the material is grouped and which form the starting point for the interminable and inconclusive analyses, antithesis, and synthesis beloved by specialists'.

4. Explanatory study, 'which tries to show the root and reason of what is said or written, so that what finally emerges is a nexus of influence and interaction'.

5. Selective study, which chooses a few theologians and makes a fuller exposition of selected pieces.

Consequently, Bromiley understands that both the aim of historical theology and the methodology applied to advance historical theology will inherently impose selectivity. He acknowledges the subjective nature of this selectivity (Bromiley 1978):

In neither sphere can any definitive criteria be found by which to make the selection … Hence the final choice has an arbitrary element in which circumstances and preferences play a major part.

The final person referred to in both articles to define historical theology is British Anglican theologian, Alister E. McGrath, the foremost contemporary voice promoting historical theology. In the intensity and consuming reality of the present, we can too easily overlook the insight that all theology has a history (McGrath 2001). The particular concern of historical theology is therefore to lay bare the connections between historical context and theology (McGrath 2001). Historical theology is, for McGrath, a branch of theology which aims to explore the historical situations within which these ideas developed or were specifically formulated. The universality of God's saving action is necessarily embedded in the experiences of particular cultures and, argues McGrath, 'is shaped by the insights and limitations of persons who were themselves seeking to live the gospel in a particular context' (McGrath 2001). Christianity inevitably and often unconsciously absorbs ideas and values from its cultural backdrop. Historical theology is not simply a Christian rendering of history, but something more subversive in nature, seeking to 'indicate how easily theologians are led astray by the self-images of the age' (McGrath 2001).

There have been numerous other voices providing important insights whilst not expressly labelling it as historical theology (Dreyer 2017). German theology philosopher, Martin Heidegger placed the question of human existence and historicity in the centre of theological debate (Dreyer & Pillay 2017). German Lutheran theologian, Rudolf Bultmann had an affinity for Heidegger and entered into the debate on the objectivity of historical research and historical knowledge (Dreyer & Pillay 2017). Wolfhart Pannenberg, another German Lutheran theologian, advanced the idea that all theology is practised within a specific historical context; one of the central questions of theology therefore is the relation between faith and history. Swiss Reformed theologian, Karl Barth placed much emphasis on the dialectical tension between time and eternity or between humanity and God, describing history as a conversation between past and present wisdom (Dreyer & Pillay 2017). Barth had a major influence on the younger theologians Ebeling, Bromiley and McGrath and shaped their understanding of what was to become defined as historical theology.

Given my own subjective vantage point, I value the voice of the former Anglican Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams. He argues that an ignorance and detachment from our past in fact handicaps the church (Williams 2005):

A Church that shares the widespread and fashionable illiteracy of this culture about how religious faith worked in other ages is grossly weakened in its witness. That witness has to do with a promise of universal community that is grounded not in assumptions about universal right and reason but in a narrative displaying how communication is made possible between strangers by a common relatedness to God's presence and act in history - in an historical person. (p. 113)

Williams sees the past as a set of stories we tell in order to understand better who we are and the world we are now in (Williams 2005). He likens our relationship to the past as to a foreign country and to historical characters as to strangers (Williams 2005):

Good history makes us think again about the definition of things we thought we understood pretty well, because it engages not just with what is familiar but with what is strange. It recognizes that 'the past is a foreign country' as well as being our past. (p. 1)

Furthermore, Williams suggests that good historical writing is one that makes the familiar become unfamiliar in order to make it clearer; in other words, our identity now is:

[B]ound up with a whole range of things that are not easy for me or us, not obvious or native to the world we think we inhabit, yet which have to be recognized in their solid reality as both different from us and part of us. (Williams 2005:20)

For good or ill, we are more indebted to our theological past than we will ever truly realise, because (Williams 2005):

Who I am as a Christian is something which, in theological terms, I could only answer fully on the impossible supposition that I could see and grasp how all other Christian lives had shaped mine, and more specifically, shaped it towards the likeness of Christ … I do not know, theologically speaking, where my debts begin and end. (p. 27)

Williams cautions that the characters that historical theologians engage with, and to whom all Christians are indebted to various degrees, 'are not modern people in fancy dress; they have to be listened to as they are, and not judged or dismissed - or claimed or enrolled as supporters - too rapidly' (Williams 2005:11). He also cautions against seeking a definitive history and argues rather that 'We don't have a single "grid" for history; we construct it when we want to resolve certain problems about who we are now' (Williams 2005:5). There is a fine balancing act between seeking continuity - linking of the present with the past in a manner that is familiar - and discontinuity - seeing the strangeness of the past in regard to the present - in history. Yet, this is an important balancing act and central to the task of historical theology. Williams argues that 'the risk of not acknowledging the strangeness of the past is as great as that of treating it as purely and simply a foreign country' (Williams 2005). In other words, there are two extremes to be avoided: seeking flawless continuity with the past and thinking who we are now and what we believe as being completely discontinuous with all that has gone before. Williams, like Bromiley, also recognises the ultimately arbitrary method of engaging with the past and trying to make sense of it or interpret for the present. He posits that (Williams 2005):

[T]he true Church has no real history, since it is always that community of persons (not wholly coterminous with its membership of the visible institution, in which there will always be those not fully obedient to God) in whose lives the kingdom has come. (p. 16)

This paradox between the visible and invisible church throughout time, between the strangeness and foreignness of the past and between the sense of continuity and discontinuity with our present forms of Christianity create many challenges in the study of historical theology. But the challenge is no less important and Bromiley and McGrath outline several benefits to historical theology laying claim to the throne of church history, inter alia:

-

It shows how the church has moved across the centuries and continents with an ongoing continuity in spite of every discontinuity (Bromiley 1978).

-

It offers examples of the way in which, and the reasons why, the conformity of the church's word to God's Word has been achieved or compromised in the different centuries and settings (Bromiley 1978).

-

It brings a valuable accumulation of enduring insights as well as relevant warnings to today's church (Bromiley 1978).

-

It demonstrates that certain ideas came into being under very definite circumstance and that, occasionally, mistakes have been made (McGrath 2001).

-

It maintains openness that theological development is not irreversible, and the mistakes of the past may be corrected (McGrath 2001).

Bromiley, like Williams, cautions against a theological arrogance in our approach to a theological engagement with History so that (Bromiley 1978):

[T]he criticism will be constructive, not condemnatory… and both criticism and approval will be undertaken with humility, for is not the historical theologian himself a participant whose work comes under the same test?

Historical theology in South Africa through the eyes of Dreyer and Pillay

Following Bromiley, both Dreyer and Pillay argue that historical theology is first and foremost theology, and therefore, proponents of historical theology are theologians not historians, although they may make use of research methods associated with historical enquiry (Dreyer 2017; Dreyer & Pillay 2017). The traditional approach to church history has been to divide history into four periods (Early Church, Medieval Period, Reformation and Modern Period), then to describe the main personalities and events in each era. Both Bromiley and McGrath followed the same pattern with their approach to historical theology. Dreyer and Pillay depart from Bromiley and McGrath.

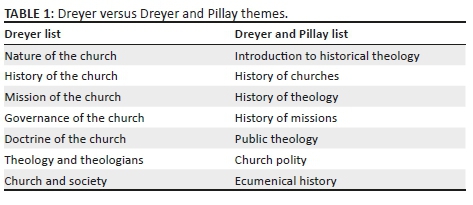

Dreyer thinks that historical theology could include seven themes with a strong historical and ecclesiological focus (Dreyer 2017). Material should be structured within a matrix that connects the nature of the church to the history, mission, practice and governance so that it can function within a coherent structure, one that facilitates learning and open discussion. In their combined views, Dreyer and Pillay refine the concept. The same argument is advanced that historical theology should have a thematic structure which enables a contextual approach to interpreting history, especially a reading of history that empowers the quest for Africanisation as well as decolonised narratives. The themes have been arranged in Table 1 above for ease of reference.

Dreyer and Pillay (2017) use a slightly broader title in subsection one, 'Introduction to historical theology', as opposed to Dreyer's (2017) 'Nature of the church'. This allows for the question 'What is the church?' (or the nature of the church) to be addressed but also the critical questions 'What is history?' and 'What is the meaning of history?' The aim is to make sense of the past, trying to understand not only what has happened but why things happened.

Subsection two, 'History of the church' versus 'History of churches', is similar on both counts; only the former gives the impression of something definitive, which is not the intent. In both papers, the authors acknowledge that a definitive history is not possible and that local relevance should be established, of doing 'history from below', as articulated by Vosloo (2009).

A similar critique can be levelled with Dreyer's subsection three, 'Mission of the church', which in Dreyer and Pillay (2017) is listed fourth as 'History of missions'. Both are rooted in understanding the church as being part of the mission Dei, albeit that the involvement of churches in the world throughout the ages has creative controversy and conflict through its very many missions, something the latter title gives greater nuance to.

The governance or polity of the church is outlined in Dreyer's fourth (2017) theme and sixth subsection in Dreyer and Pillay (2017). This is a nod to the fact that church polity and church history have traditionally always been part of the same department. Church order arises in relation to specific historical contexts, and these contexts change, which historical theology brings to the fore.

Dreyer's fifth and sixth (2017) themes are 'Doctrine of the church' and 'Theology and theologians', which have been combined into a single subsection by Dreyer and Pillay (2017) as 'History of Theology'. This possibly makes more sense, seeing that theologians, their theologies and the shaping of the doctrines of the church are inextricably linked. Understanding this historical background is crucial to seeing how the past interacts with and can be applied to the present. I agree with Dreyer that 'historical theology finds its most lucid expressions in the study of theologians and theology through the centuries' (Dreyer 2017).

With the combining of 'Doctrine of the church' and 'Theology and theologians' into 'History of theology', Dreyer and Pillay (2017) are able to add Ecumenical history as a subsection seven in and of itself. The authors maintain that 'tracing the origins, work and witness of these ecumenical movements is imperative in understanding and appreciating the history of the church in the world'. More importantly, it provides a way to counter one of the initial critiques of church history that church historians tended to place more emphasis on the theological and ecclesiastical identity of their own denominations. This opens windows on a wide range of interactions and emphases.

Dreyer's seventh and final theme, 'Church and society' morphs into the subsection 'Public theology' (subsection five). This inclusion is controversial. Public theology is establishing itself as a separate theological discipline. But Dreyer and Pillay (2017) advance a convincing argument that 'public theology requires sound knowledge of social and ecclesial history' and has to 'tread carefully in order to avoid the pitfalls of generalisation, lack of nuanced historical discourse, exclusivism, hypocrisy and pessimistic world view'.

A theme hinted at

Dreyer (2017) argues that ecclesiology should be the cornerstone of historical theology, although it should not be limited to ecclesiological questions. One theme that can come under ecclesiology is the study of the trans-disciplinary context, which Dreyer (2017) mentions. A relevant example from the trans-disciplinary context is the link between the natural sciences and environmental theology, which when stated sounds obvious but is also the remit of historical theology. Both science and religion have arisen in specific historical contexts and have interacted to shape the language and thought of the other, hence the topic being perfectly suited to the domain of historical theology. Science and religion are inextricably linked.2 It was only as the discourse of environmental science developed that it gave rise to the theological language that is now normative in green theology or eco-theology. The Historical Theological methodology can be applied to specific streams within theology such an evangelicalism in relation to environmental science, which Peter Houston (2018) has done by examining the socio-political and environmental events that were formative in the early Lausanne Congresses and the fruition of these dynamics in Cape Town 2010. Not only is there a recognised 'green' theology from the end of last century, but an emerging 'blue' theology in light of water scarcity becoming a critical issue in the 21st century. Tentative theological streams of thought on water are emerging in what has variously been described as 'hydrotheology' (Russell 2007), 'aquacentric theology' (De Gruchy 2010) and 'blue theology' (Ferris 2014) and collectively engaged with in a South African context by Marais (2017). Ched Myers, who is perhaps most well-known for Binding the Strong Man - A Political Reading of Mark's Story of Jesus (Myers 1988), one of the earliest commentaries to take an empire-critical view. Much of Myers' subsequent teaching and activism has been linked to issues of peace and justice, but in recent years has metamorphosed into environmental justice, especially to do with water (Houston 2019). He is a contemporary example of how theologians and their theologies evolve over a life time, something that historical theology uniquely gives space to consider.

This space in historical theology is important because it can be a creative space for the exploration of theological ideas, dialoguing with other academic disciplines. The widening spectrum of scientific and theological reflection has encompassed much of the natural sciences as was evidenced in the August 2013 volume of Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae that celebrated the work of Professor Cornel du Toit. But there are disciplines like geomorphology that are still far removed from reflections on the human person and thus not a traditional point of departure for theological engagement. Houston (2013, 2014) has brought some key concepts from geomorphology such as the ideas of inter-connectedness, holism and scale perspectives into conversation with what could be called 'geo-theology'.

Whilst the trans-disciplinary aspect of historical theology has been hinted at in the structure laid out by Dreyer (2017) and Dreyer and Pillay (2017), its profile is marginal. No specific mention is made of the significance to historical theology of an orientation that is not only towards the social sciences and public theology but also towards the natural sciences, seeing that in large measure it is our theologies that motivate the valuing or destruction of God's world.

Conclusion

Both Dreyer and Pillay, separately and collaboratively, have offered profound reflections on historical theology as a theological discipline in its own right, stepping out of the shadow that church history has long cast in South Africa. Their argument is advanced and affirmed that, when properly structured, historical theology has a major role to play in enriching theological conversations that are important to the ongoing transformation, if not reformation, of the church. However, given my bias, it is perhaps inevitable that I also conclude that more needs to be made of the potential for these theological conversations to be trans-disciplinary in nature. Church history is dead, long-live historical theology!

Acknowledgements

The discussion on historical theological methodology is drawn from my Master of Theology (M.Th.) in church history and Polity, 'Roots That Refresh: An Historical-Theological Engagement with Jewish Meal Traditions and the Celebration of the Eucharist in the Anglican Church' (2007), awarded by the University of Stellenbosch. This amounts to about 11% of the article.

Competing interests

The author declares that no competing interest exists.

Author's contributions

I declare that I am the sole author of this research article.

Ethical consideration

This article followed all ethical standards for a research without direct contact with human or animal subjects.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the author.

References

Bromiley, G.W., 1978, Historical theology: An introduction, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

De Gruchy, S., 2010, 'Water and spirit, theology in the time of cholera', The Ecumenical Review 62(2), 188-201. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-6623.2010.00057.x [ Links ]

Denis, P., 1997, 'From church history to religious history: Strengths and weaknesses of South African religious historiography', Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 99, 84-93. [ Links ]

Dreyer, W.A., 2017, 'Teaching historical theology at the University of Pretoria - Some introductory remarks', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 73(4), a4596. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v73i4.4596 [ Links ]

Dreyer, W.A. & Pillay, J., 2017, 'Historical theology: Content, methodology and relevance', in D.J. Human (ed.), Theology at the University of Pretoria - 100 years: (1917-2017) Past, present and future, pp. 117-131. https://doi.org/10.4102/ve.v38i4.1680 [ Links ]

Ferris, M.H., 2014, 'Sister water: An introduction to blue theology', in S. Shaw & A. Francis (eds.), Deep blue: Critical reflections on nature, religion and water, pp. 195-212, Routledge, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Houston, P.C., 2013, 'A cross disciplinary conversation on landscape process', Scriptura 112. https://doi.org/10.7833/112-0-83 [ Links ]

Houston, P.C., 2014, 'Exploring the landscape of historical theology through the lens of geomorphology', Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae 40(1), 273-289. [ Links ]

Houston, P.C., 2018, 'The long road to Cape Town 2010 and an evangelical response to a global environmental crisis', Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 161, 54-70. [ Links ]

Houston, P.C., 2019, 'Blue theology and watershed discipleship in South Africa', Acta Theologica 39(2), 31-47. https://doi.org/10.18820/23099089/actat.v39i2.3 [ Links ]

Marais, N., 2017, '#RainMustFall - A theological reflection on drought, thirst, and the water of life', Acta Theologica 37(2), 69-85. https://doi.org/10.18820/23099089/actat.v37i2.5 [ Links ]

McGrath, A.E., 2001, Christian theology: An introduction, Blackwell Publishers, Oxford. [ Links ]

Myers, C., 1988, Binding the strong man - A political reading of Mark's Story of Jesus, Orbis, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Ross, K.R., 1997, 'Doing theology with a new historiography', Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 99, 94-98. [ Links ]

Russell, C.A., 2007, 'Hydrotheology: Towards a natural theology of water', Science and Christian Belief 19(2), 161-184. [ Links ]

Vosloo, R., 2009, 'Quo vadis church history?: Some theses on the future of church history as an academic theological discipline', Scriptura 100, 59-60. https://doi.org/10.7833/100-0-653 [ Links ]

Williams, R., 2005, Why study the past? The quest for the Historical Church, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Peter Houston

rector@stagnes.org.za

Received: 05 Oct. 2019

Accepted: 09 Mar. 2020

Published: 13 May 2020

1 . Department of Christian Spirituality, Church History and Missiology, viewed 05 October 2019, from https://www.unisa.ac.za/sites/corporate/default/Colleges/Human-Sciences/Schools,-departments,-centres,-institutes-&-units/School-of-Humanities/Department-of-Christian-Spirituality,-Church-History-and-Missiology.

2 . Alistair McGrath, the major proponent of historical theology, is now Andreas Idreos Professorship in Science and Religion in the Faculty of Theology and Religion at the University of Oxford, having relinquished being Professor of historical theology.