Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

HTS Theological Studies

versión On-line ISSN 2072-8050

versión impresa ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.76 no.4 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v76i4.5859

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

The Matthean characterisation of Jesus by angels

Francois P. Viljoen

Church Ministry and Leadership, Faculty of Theology, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Angels play a significant role in the characterisation of the Matthean Jesus. The Gospel of Matthew displays particular interest in angels. This article focuses on passages in Matthew that relate the role of angels directly to Jesus. Matthew distinguishes between the angel of the Lord and angels in general. This article examines the latter group keeping in view their support of Jesus. It shows that Matthew assumes knowledge of Jewish angelic traditions among his readers. He adds new perspectives to their knowledge about the relation of angels with Jesus. He is depicted as meek and humble, refraining from using his authority to call on the assistance of angels for his own benefit. Yet angels come with reverence to serve him. In humility, he fully submits to the will of the Father by entering his passion. On the other hand, he is also depicted with eschatological glory as being accompanied by all the angels. Heavens are emptied to attend to the Son of Man on his glorious throne. With an entourage of all heavenly angels he will return as the eschatological judge not only to judge all the nations, but also the devil and his angels.

Keywords: characterisation; Matthew; narrative; angel; Jesus; judge; eschatology; narrative criticism.

Introduction

This article follows a narrative approach1 to examine the way in which angels2 in the Matthean Gospel characterise Jesus. Characterisation can be achieved in various ways. One of these would be through the actions and words of a character and how other role-players in the text interact with that character. The Gospel of Matthew usually groups angels together with Jesus in the same context. He forms the principal character, the protagonist. There are only a few 'scenes' where he is not personally present. However, all scenes relate to him. His teachings and actions are in the spotlight, and the actions of other characters all pertain to him. The angels therefore count among many other characters3 who support Jesus. This suggests that a study of Matthew's portrayal of angels in relation with Jesus will enhance the understanding of Matthew's portrait of Jesus and Matthew's Christology.

Though angels may be considered as minor characters in Matthew's Gospel, this Gospel displays particular interest in them. It frequently refers to angels. The angel of the Lord appears three times in the birth and childhood narratives, involving material that is unique to the First Gospel (Mt 1:18-25; 2:13-15 and 2:19-23). In the temptation scene, the devil deceptively refers to angels and once he has left, angels come and serve Jesus (Mt 4:1-11). When Jesus speaks of eschatological scenes around the coming of the Son of Man, he repetitively mentions the role of angels in judgement and punishment (Mt 13:24-30, 36-43, 47-50; 16:27; 24:30-31, 36 and 25:31-46). In a remark unique to Matthew (Mt 18:10), he also speaks of angels of the little ones who are always before the face of the Father. In his dispute with the Sadducees and Pharisees, Jesus again refers to angels in heaven (Mt 22:30). In a remark that is once again unique to this Gospel (Mt 26:53-54), when he is arrested in Gethsemane, Jesus mentions his ability to call in the assistance of 12 legions of angels. At the empty tomb the angel of Lord appears again (Mt 28:2-10), a character whom Mark identifies as a young man (Mk 16:5), although Luke speaks of two men (Lk 24:4).

The scope of the present article is limited to passages where the role of the angels is directly related to Jesus. Matthew distinguishes between the angel of the Lord and angels in general. This article focusses on the latter group of angels in their support of Jesus as the main character of the narrative.

Angels at the temptation (Mt 4:6 and 11)

Matthew and Luke differ from the concise version of Mark, since they add the dialogue between Jesus and the devil during the three separate temptations (Mt 4:1-11; Lk 4:1-13).4

Matthew's version clearly echoes the wandering of Israel (Bendoraitis 2015:56; Davies & Allison 2004a:353). Jesus faces temptations similar to those that the Israelites experienced. He responds to each temptation by referring to passages from Moses' address before they entered the Promised Land (Dt 6-8).5

The voice of God at Jesus' baptism seems to echo the voice of the Lord calling Israel to obedience in Deuteronomy 4:36, that is: 'From heaven he made you hear his voice to discipline you…' Israel's tempering struggle proved to be a time of disciplining and humbling. In contrast to Israel's disobedience, Jesus remains faithful. Nevertheless, God protected his people during their 40 years in the wilderness.

Its double reference to angels (Mt 4:6 and 11) makes Matthew's temptation narrative unique.

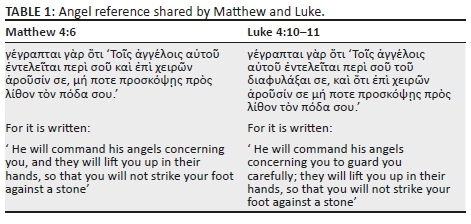

The first reference to angels that Matthew shares with Luke (Mt 4:6; Lk 4:10-11) is indicated in Table 1.

In the second temptation, according to Matthew's version, the tempter takes Jesus to the temple.6 For Israel, the temple symbolised God's presence and protection (cf. Nm 10:35; 2 Sm 15:25). The temple would be the place where one would be most sure of God's protection. The tempter challenged Jesus to jump from the pinnacle of the temple, concomitant with an almost verbatim quotation7 from the Septuagint (Ps 90:11-12 LXX), which also carries the pretence that God would send his angels to protect him.

Since the Matthean Gospel reflects a strong Jewish character, the angel traditions of the Old Testament and Jewish literature from the Second Temple Period provide context to Matthew's references to angels. For instance, consider that Psalm 91 is a song about God's protection of those who put their trust in him. Creach (1996:94) labels Psalm 91 as a 'kind of microcosm of all the refuge language of the Psalter'.

God commands his angels to carefully protect those who seek his refuge from all dangers. The angels become a divine guard against all kinds of threats. Beyond this psalm, angels are frequently portrayed as agents of God's protective care. Angels deliver Lot and his family from Sodom (Gn 19), they protect the three men in the furnace (Dn 3:28), Daniel declares that God sent his angel to shut the mouth of the lions (Dn 6:22) and God promises his protecting angel to guide his people on their exodus (Ex 32:34), thus to mention but a few examples. The devil therefore draws upon a well-attested tradition around the care given by angels to tempt Jesus. However, Jesus refuses to jump, not because he denies the protection of the angels, but because he chooses not to succumb to the temptation of the devil and to be fully faithful to the will of his Father.8

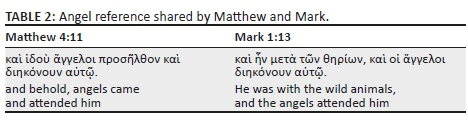

Table 2 presents the second reference to angels that Matthew shares with Mark (Mt 4:11; Mk 1:13).

Matthew omits Marks' remark that Jesus was among the wild animals. The wild animals probably refer to evil characters, such as the lion and adder as found in Psalm 91:11-13.9 Mark 1:13 therefore implies that Jesus conquered these evil characters (Bendoraitis 2015:69).10 In contrast to these, the angels came and served him. The hostile animals in Mark therefore create a parallel with Jesus' defeat of the devil in Matthew's extended version of the temptation narrative. While Mark mentions Jesus' defeat of the wild animals, Matthew describes how Jesus defeated the Satan so that he left.

At the end of this short narrative, both Matthew and Mark mention that the angels served him (διηκόνουν αὐτῷ).11 Matthew adds ἰδοὺ (behold) and inserts the extra verb προσῆλθον (came). Each time Matthew mentions the appearance of an angel, he inserts the term ἰδοὺ as an interjection (Mt 1:20; 2:13, 19; 4:11; 28:2) to emphasise the importance of the intervention by that angel and the angel's interaction with a character.

However, Matthew relates very little about the angels as such. He probably assumes knowledge of the traditions about angels. Instead of describing the angels,12 he relates their activities. The addition of προσῆλθον signifies reverence, since Matthew usually uses it in relation to worship (Mt 8:2; 9:18; 20:20; 28:9; Bendoraitis 2015:71). The contrast with Matthew 4:3 is noteworthy because the same lexeme is used to describe how the tempter slyly approached Jesus (προσελθὼν ὁ πειράζων). Yet, when the devil left (τότεἀφίησιν αὐτὸν ὁ διάβολος), the angels came (ἄγγελοι προσῆλθον) and served him. This suggests the majesty of Jesus.

Parallel to Mark, the angels in Matthew served (διηκόνουν) Jesus. The temptation narrative begins where he fasts for 40 days, and the devil subsequently tempts him to turn stones into bread. But Jesus rejects this.

At the end of the narrative, the angels then come to nourish him. The parallel with Elijah (1 Ki 19:5-8) is significant. He also received nourishment from the angel of the Lord. In another instance, in the desert Israel received nourishment from the Lord. However, this was after they had complained about their hunger (Ex 16:2-3), while Jesus was attended without his request or complaint (Davies & Allison 2004a:373).

The presence of the angels after Jesus demonstrated his unreserved obedience to the will of God echoes the promise of God's protection by angels in Psalm 91. Instead of the relying on the protection of angels by succumbing to the temptation of the devil to jump from the temple, the angels now come to serve him. The presence of the angels demonstrates God's appreciation of Jesus' faithfulness while being severely tempted.

In sum, it is clear that the angels in the temptation narrative portray Jesus' victory over Satan and his unwavering obedience to the will of God.

Angels at the judgement (Mt 13:24-30, 36-43, 47-50)

The parable discourse of Matthew 13 forms the end of a section in which Jesus experiences severe opposition from the Pharisees and the teachers of the law (Mt 11-13). The eschatological separation of the good and the evil is a prominent motif in this discourse. Angels appear in the parables of the weeds (Mt 13:24-30, 36-43) and the net (Mt 13:47-50). These refer with vivid apocalyptic language13 to the role of the angels. The Son of Man is portrayed as the eschatological judge commanding the angels14 to gather and separate the righteous from the wicked.15

The parables of the weeds and of the net each enjoy separate explanations of their meanings. Their explanatory parts contain descriptions of the angels. Although it is not unusual for parables to contain concluding remarks to aid their understanding, only three of them have extended explanations, namely the parable of the sower (Mk 4:1-9, 13-20; Mt 13:1-9, 18-23; Lk 8:4-8, 11-15), the parable of the weeds (Mt 13:24-30, 36-43)16 and the parable of the net (Mt 13:47-50). Matthew 13 contains all three of these parables of which two appear only in Matthew. It is significant that angels are mentioned in the explanations of the two parables that are unique to Matthew. Although scholarly debate exists regarding the question as to whether these additions form part of the original parable and whether it should guide their interpretation, the present article adopts a narrative approach, that is, reading them within the narrative framework provided by the evangelist himself (cf. Gerhardsson 1991:325; Snodgrass 2008:34).17

Parable of the weeds (Mt 13:24-30, 36-43)

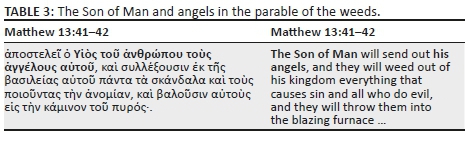

As mentioned earlier, the parable of the weeds (Mt 13:24-30) is unique to Matthew. The Matthean Jesus tells this parable to the crowds, but when alone with his disciples, he explains its meaning (Mt 13:36-43).

The explanation describes the relationship between the Son of Man and the angels18 at the end of times. The harvesters in the parable are equated with angels. The Son of Man sends out his angels to collect and separate the evil from the righteous (Mt 13:41-42), as the harvesters of the parable would separate the weeds from the wheat (Mt. 13:30). The harvesters had to burn the weed, although they had to bring the wheat into the barn. This action is equated with the task of the angels at the end of time.

The parable describes how the angels will act as agents of the Son of Man to gather the wicked and punish them (see Table 3). This activity reflects traditions of angelic involvement associated with eschatological judgement (Bendoraitis 2015:82-90; Luz 2001:385). The Old Testament mentions angels that participate in God's judgements, for example the two angels that announced the judgement of Sodom and Gomorrah (Gn 19:15). The final plague of the death of the firstborn is executed by an angel (Ex 11:14; 12:12, 23, 29). In the literature of the Second Temple Judaism, angels frequently appear as instruments of eschatological punishment.19 The first book of Enoch refers frequently to angels in this role. In reaction to injustice, God sends his obedient angels to collect, bind and punish guilty angels (1 En 9.1-3). In 1 Enoch 100.4, angels act as agents of God's punishment by gathering all the wicked for their condemnation. Some of the Dead Sea Scrolls reflect similar traditions. 1QS 4.12 and CD 2.5-6 describe how angels, obedient to God, inflict punishment on the wicked. In the Testament of Abraham, angels have specific roles in the execution of judgement. They are portrayed as maintaining a balance, weighing good and bad deeds as part of a person's judgement (T. Abr 10-13). The Book of Revelations describes the involvement of angels in God's judgement (for instance, in Rv 8:6-9:21; 12:7; 19:14; and so forth). The Apocalypse of Peter also describes the role of angels as gathering sinners for judgement, inflicting punishment and clothing the righteous in garments for eternal life (Ap. Pt 3).

However, the interaction between the Son of Man and the angels does not have specific antecedents. The closest parallels found in the Old Testament might be from Zechariah 14:5: 'The Lord my God will come, and all the holy ones with him' as well as Daniel 7:10 where the Son of Man is at the throne of the 'Ancient of Days' where 'thousands upon thousands attended him; 10 000 times 10 000 stood before him'.

Although the parable of the weeds reflects traditions of angelic activity in the execution of end time judgement, the parable explicitly links this judgement to the Son of Man. Although Matthew draws on traditions as recorded in Jewish apocalyptic texts, he adapts them to include the position of Jesus within this cosmological hierarchy. Other than in the Testament of Abraham, the angels in the parable do not act as judges. The judgement comes from the Son of Man, and he sends out (ἀποστελεῖ) his angels to execute his commands. Not only are the angels sent by him, but they are also his (αὐτοῦ) angels. His angels stand under his direction. This underscores the importance of his character in Matthew's Gospel. The Son of Man is the authoritative judge of the end time.20

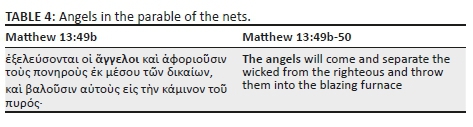

The parable of the net (Mt 13:47-50)

Angels are again mentioned in the parable of the net. It draws the parable discourse of Matthew 13 to an end. It is much shorter than the parable of the weeds, though its structure and vocabulary are similar (Davies & Allison 2004b:440). Although the Son of Man is not explicitly mentioned in this parable, it recalls the role of the Son of Man in the parable of the weeds. By repeating the same idea, the Gospel emphasises the eschatological judgement, as presented in Table 4.

As in the parable of the weeds, the angels will collect the good and the bad, separate them, destroy the bad and preserve the good. Although the role of the Son of Man is not explicitly mentioned, it is implied. As with the parable of the weeds, the angels execute their tasks under his direction.21

In these two parables, angels are portrayed as subject to the control of the Son of Man. He is the powerful judge under whose direction they stand.

The Son of Man and his angels (Mt 16:27)

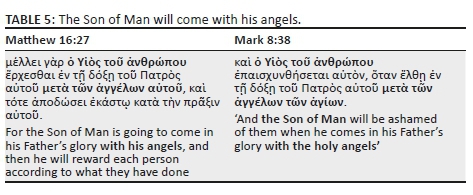

After Matthew 13, Matthew 16:27 is the next passage in the narrative referring to the angels and the Son of Man. It reveals once more that angels are in the service of the Son of Man, as the heavenly and eschatological judge. Although the parables of the weed and the net are unique to Matthew, Matthew 16:27 has a parallel passage in Mark 8:38, as reflected in Table 5.

The Matthean version differs slightly from the Markan one. Matthew omits the reference to the shame of the Son of Man (ἐπαισχυνθήσεται αὐτὸν) and moves the eschatological coming of the Son of Man to the beginning of the phrase. In this way, he places more emphasis on the immanence of his coming. Furthermore, he changes τῶνἀγγέλωντῶνἁγίων [holy angels] to τῶνἀγγέλων αὐτοῦ [his angels].

Mark probably draws on the tradition that God is the holy one, with the result that the angels that are associated with him are holy angels (Bendoraitis 2015:121). As indicated, in Matthew there is a shift in emphasis that describes the angels as belonging to the Son of Man.22 This does not imply that they are no longer holy or God's angels, but rather that they are portrayed as enjoying a relationship with the Son of Man. Besides indicating the relationship, the pronoun αὐτοῦ [his] also suggests Jesus' authority and the angels' obedience. Despite the fact that Matthew 16:27 does not explicitly mention that the Son of Man sends or commands the angels, it implies a relation with Matthew 13:41 where the Son of Man sends his angels to perform acts of judgement. The Son of Man is moreover portrayed in a way normally associated with God. This idea is reinforced by the statement that the Son of Man is coming ἐντῇδόξῃτοῦ πατρὸς αὐτοῦ, that is, in his Father's glory.

Matthew 16:27 stands at a crucial point in the narrative. It follows shortly after Peter's confession about the identity of Jesus, who poses the question: 'Who do people say the Son of Man (τὸνυἱὸντοῦἀνθρώπου) is?' (Mt 16:13). Consider that unlike Matthew, Mark and Luke do not include the reference to 'the Son of Man' but only 'Who do people/the crowds say I am?' (Mk 8:27; Lk 9:18). By explicitly referring to 'the Son of Man', Matthew emphasises the importance of Jesus' identity. To the question 'Who do you say I am' (Mt 16:15), Peter responds: 'You are the Messiah, the Son of the living God' (Mt 16:16). The passage that follows immediately about Jesus on the Mount of transfiguration (Mt 17:1-8) further reveals his identity. It is therefore clear that the redactional change of 'holy angels' to 'his angels' in Matthew 16:27 puts significant emphasis on the status of Jesus as Son of Man (Bendoraitis 2015:124; Davies & Allison 2004b:675). Thus, Matthew uses the angels to advance the portrait of Jesus.

The Son of Man and the angels at the judgement (Mt 24:30-31; 25:31)

In Matthew 24:30-31 and 25:31 angels are again used to express the status of Jesus as Son of Man.

The glorious arrival of the Son of Man with his angels (Mt 24:3-31)

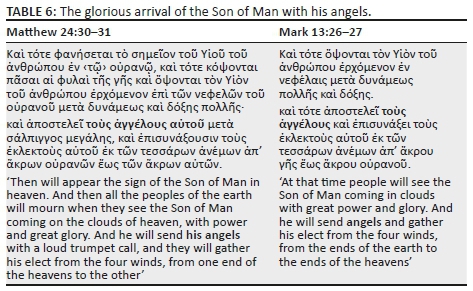

Matthew draws on Mark 13:26-27 to portray the glorious arrival of the Son of Man with his angels, as depicted in Table 6, whereas Luke omits this description entirely.

Matthew describes the cosmic signs that will signal the coming of the Son of Man.23 Both Mark and Matthew quite narrowly echo the words of Daniel 7:13 LXX about the sign of the Son of Man.24 Matthew adds an allusion to Zechariah 12:10 in which the nation mourns (Keener 1999:586; Luz 2005:201).25 The Son of Man comes ἐπὶ τῶννεφελῶντοῦοὐρανοῦ, that is, on the clouds of heaven, and µετὰδυνάμεως καὶ δόξης πολλῆς, that is, with power and great glory. He is enthroned on the clouds like Yahweh in Psalm 104:3 and Isaiah 19:1 (Luz 2005:201). However, where Matthew 16:27 (par. Mk 8:38) mentions that the Son of Man will come in the glory of his Father, Matthew only refers to the glory of the Son. This confirms the recognition that the Son is depicted with authority, power and glory as the eschatological Son of Man.26

The role of the angels once again emphasises the Son of Man's position as judge. He has the authority to send 'his angels' (τοὺςἀγγέλους αὐτοῦ) to gather 'his elect' (τοὺςἐκλεκτοὺς αὐτοῦ) (Keener 1999:585). In addition to Mark's version, Matthew adds the blast of the trumpet (μετὰσάλπιγγος μεγάλης) and, as in Matthew 16:27, identifies the angels as 'his' (αὐτοῦ). Matthew's readers would have recognised the eschatological significance of the blowing of the trumpet (Luz 2005:203).27 With the sounding of the trumpet and the darkening of the sun and moon when the stars fall from heaven (Mt 24:29), the only light will be that of the glory of the Son of Man (Davies & Allison 2004c:363). All attention will be drawn to the Son of Man as he sends out his angels to gather the elected ones.

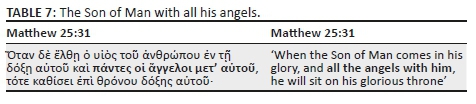

The arrival of the Son of Man with all his angels (Mt 25:31)28

The parable in Matthew 25:31-46 continues to build this high Christology into its narrative (Keener 1999:602). It provides the most elaborate demonstration of the glory of the Son of Man as the eschatological judge. The passage does not have a parallel in Mark or Luke. In Matthew 25:31, the Son of Man and his angels are mentioned in elaborate terms, as shown in Table 7.

Matthew has been building up the portrayal of the Son of Man. In Matthew 16:27 he refers to the glory of the Son, instead of that of God the Father.29 Furthermore, he describes the angels accompanying the Son of Man (µετ' αὐτοῦ). In Matthew 25:31 the narrative reaches a climax as πάντεςοἱἄγγελοι, that is, all the angels arrive with him when he comes to sit on his glorious throne (Bendoraitis 2015:171; Davies & Allison 2004c:420; Luz 2005:276). All the heavenly angels are commanded by the Son of Man when he sits on this throne. Matthew here depicts a contrasting image of the devil and his angels. He underlines that the devil and his angels will be punished with eternal fire (Mt 25:41). The Son of Man has power over all evil.30

From his throne of glory and with an entourage of all the heavenly angels, he will pass judgement not only over all the nations, but also over the devil and his angels.

Angels at the arrest in Gethsemane (Mt 26:53)

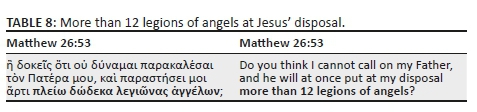

At his arrest, Jesus announces that he could appeal to the Father and he would at once send 12 legions of angels (Mt 26:53). Though all four Gospels narrate the arrest of Jesus, Matthew includes a singular statement about the help of the angels, as portrayed in Table 8.

In what seems to be an attempt to protect Jesus, one of his disciples31 draws his sword and cuts off the ear of the high priest's servant. Jesus immediately responds by telling him to put away his sword, as there will be no need for it, since he has the ability to appeal to his Father, who would send more than 12 legions of angels to protect him. In Jewish tradition, angels are often depicted as ready to protect God's people in battle with evil forces.32 As a legion comprises 6000 troops, this would amount to more than 72 000 angels. Besides the significant number of angels, the number 12 has a rich symbolic connotation. The number of angels are even more overwhelming when considered that one angel could single-handedly kill 185 000 Assyrians (2 Ki 19:35; 2 Chr 32:21; Is 37:36).

Jesus refuses to demonstrate his authority in such a manner. This is reminiscent of his response to the devil with his second temptation, when the devil tempted him to jump from the temple, as angels would carry him (Mt 4:6). Jesus could once again call on his Father to send angels to assist him. In both situations Jesus does not do so, as this would imply misunderstanding of and disobedience to the will of the Father. Instead, he demonstrates his complete knowledge and obedience to the will of the Father. He has come to serve, and not to be served. The Son of God, to whom all dominion in heaven and earth is given, uses his supernatural powers to the benefit of others (Davies & Allison 2004c:513). Obediently he proceeds to the cross, and he does this alone, without the assistance of angels.

Conclusion

Angels play a significant role in the characterisation of Jesus in Matthew's Gospel. Matthew does not tell who the angels are or how they relate to the Father. He assumes knowledge of Jewish angelic traditions among his readers. However, he adds new perspectives on the relation of the angels with Jesus, which enlivens his portrait of Jesus.

Jesus' unwavering commitment to God's will is expressed on two occasions with reference to angels.

Despite the possibility of angelic intervention, he does not succumb to the devil's second temptation to jump from the pinnacle of the temple expecting angels to carry him (Mt 4:6) and does not use his authority to call in the assistance of angels when he is arrested in Gethsemane (Mt 26:53). He rather submits to the will of God. He obediently enters his passion to save his people from their sins (cf. Mt 1:21).

On the other hand, Jesus' divine identity is demonstrated by the angels who reverently come and serve him (viz. (προσῆλθον καὶ διηκόνουν)) after the unsuccessful attempt of the devil to tempt him (Mt 4:11). Matthew usually uses this word group in relation to worship.

As has been demonstrated, Jesus is characterised as the authoritative eschatological judge. On judgement day, Jesus as the Son of Man will come accompanied by 'his' angels (Mt 13:41; 16:27; 24:31). Matthew's version of the event is unique, since he adds this personal pronoun, αὐτοῦ, meaning 'his'. He will be enthroned on the clouds of heaven, a position traditionally attributed to God himself. He will arrive with power and glory, and with a loud trumpet to call the elect from everywhere. He will be supported by a retinue of his angels to gather the elect and execute punishment at his command.

The contrast between Jesus as meek and humble yet also authoritative as the eschatological judge is exemplified by the depiction of Jesus in eschatological glory in Matthew 16:27. This depiction is placed between Jesus' first passion prediction (Mt 16:21) and the narrative of his transfiguration (Mt 17:1-7).

Before continuing with the Passion narrative, Jesus is climactically depicted with eschatological glory as being accompanied by all the angels (πάντεςοἱἄγγελοιμετ' αὐτοῦ) (Mt 25:31). The sun and moon will be darkened and the stars will fall from heaven. All attention will be focussed on Jesus. Heavens will be emptied to attend to the Son of Man on his glorious throne. With this entourage, as indicated, he will not only judge all the nations, but also the devil and his angels.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that no competing interests exist.

Authors' contributions

I declare that I am the sole author of this research article.

Ethical consideration

This article followed all ethical standards for a research without direct contact with human or animal subjects.

Funding information

This work was supported by a research grant from the National Research Foundation.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

References

Bendoraitis, K.A., 2015, Behold, the angels came and served him, Bloomsbury T&T Clark, London. [ Links ]

Creach, J.F.D., 1996, Yahweh as refuge and the editing of the Hebrew Psalter, Journal for the Study of the Old Testament supplement, 217, Academic Press, Sheffield. [ Links ]

Davies, W.D. & Allison, D.C., 2004a, The international critical commentary on the holy scriptures of the Old and New Testament, Matthew 1-7, T&T Clark, London. [ Links ]

Davies, W.D. & Allison, D.C., 2004b, The international critical commentary on the holy scriptures of the Old and New Testament, Matthew 8-18, T&T Clark, London. [ Links ]

Davies, W.D. & Allison, D.C., 2004c, The international critical commentary on the holy scriptures of the Old and New Testament, Matthew 19-28, T&T Clark, London. [ Links ]

Gerhardsson, B., 1966, The testing of God's son (Matt. 4:1-11 & par.) an analysis of an early Christian midrash, Conjectanea Biblica, New Testament Series 2, Gleerup, Lund. [ Links ]

Gerhardsson, B., 1991, 'If we do not cut the parables out of their frames', New Testament Studies 37(3), 321-325. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0028688500015903 [ Links ]

Gibson, J.B., 1994, 'Jesus' wilderness temptation according to Mark', Journal for the Study of the New Testament 53, 3-34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0142064X9401605301 [ Links ]

Guelich, R.A., 1989, Mark 1-8, Word, Dallas, TX. [ Links ]

Hagner, D.A., 1985, 'Apocalyptic motifs in the Gospel of Matthew: Continuity and discontinuity', Horizons in Biblical Theology 7(2), 53-82. https://doi.org/10.1163/187122085X00105 [ Links ]

Keener, G.S., 1999, A commentary on the Gospel of Matthew, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Luz, U., 2001, Matthew 8-20, Fortress Press, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Luz, U., 2005, Matthew 21-28, Fortress Press, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Snodgrass, K., 2008, Stories with intent: A comprehensive guide to the parables of Jesus, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Viljoen, F.P., 2018, 'Reading Matthew as a historical narrative', In die Skriflig 52(1), a2390. https://doi.org/10.4102/ids.v52i1.2390 [ Links ]

Witherington, B. III, 2006, Matthew, Smyth & Helwys, Macon, GA. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Francois Viljoen

viljoen.francois@nwu.ac.za

Received: 22 Oct. 2019

Accepted: 28 Jan. 2020

Published: 04 May 2020

1 . In my article (Viljoen 2018:1-10), I substantiate my narrative approach in reading the Gospels and how characterisation is accomplished by the interaction of characters in a narrative.

2 . The Greek word ἄγγελος is used to refer to celestial as well as human messengers. Although ἄγγελος is also used with reference to John the Baptist in Matthew 11:10, this article is limited to the use of ἄγγελος as related to a celestial messenger.

3 . Other characters that support Jesus in this Gospel are God the Father, the Holy Spirit, the angel of the Lord, Jesus' disciples and persons who seek healing from Jesus.

4 . This article follows the position of the priority of Mark. Matthew includes Mark's references to angels and redacts these references which reflect his interest in angels (Mk 1:13; 8:38; 12:25; 13:27, 32; cf. Mk 16:5; Mt 4:11; 16:27; 22:30; 24:30, 36; cf. Mt 28:2-3).

5 . Gerhardsson (1966) has even gone so far as to suggest that the temptation narrative is a haggadic midrash on the Shema.

6 . Luke mentions this as the third temptation.

7 . A small portion of the quotation is left out, 'to guard you in all your way'. Luke maintains a part of it, but in an abbreviated form. Davies and Allison (2004a:366) suggest that Matthew's shortening could have been intentional to symbolise the devil's distortion of the scripture. However, the temptation put to Jesus is not specifically related to the phrase 'in all your ways'.

8 . During his arrest, Jesus once again refuses to call God's angels for help, as he remains obedient to the will of his Father (Mt 26:53-54).

9 . Similar to Psalm 91, the Testament of the Twelve Patriarchs also mentions that the conquering of wild animals is the result of obedience and faithfulness to God: 'Every wild creature you will subdue' (Test. Is 7:7); 'wild animals will fear you' (Test. Benj 5.2); and the angels will bless and wild animals will flee from those who 'achieve the good' (Test, Naph 8.4).

10 . Some scholars suggest that the wild animals with Jesus refers to a return to the peaceful environment of the Garden of Eden. Jesus would then be regarded as the new Adam who conquered the Satan, which the first Adam failed to do (cf. Guelich 1989:38). However, such an interpretation is unlikely because of Mark's lack of Adam Christology and his frequent reference to wild animals as evil (cf. Gibson 1994:19).

11 . The Jewish haggadic tractate, 'Abot de Rabbi Nathan 1A, from the geonic era describes a Jewish tradition that the devil was jealous when angels prepared food for Adam. Genesis Rabba, a religious text from the Jewish classical period, notes that the devil departed once he had finished his temptation of Adam (Gn Rab. 70:8).

12 . The only description of an angel in Matthew is the angel of the Lord at the empty tomb (Mt 28:2-4).

13 . Although much of the apocalyptic material is unique to Matthew, he often heightens the apocalyptic language he shares with Mark and Luke (Hagner 1985:53). The Matthean community experienced a time of crisis, with the result that Matthew's apocalyptic perspective would encourage them in these times.

14 . In Biblical tradition, angels frequently accompany a theophany, for instance in Deuteronomy 33:2 and Psalm 68:17.

15 . Matthew frequently refers to judgement (Mt 7:23; 26-27; 13:49-50; 18; 22:11-14; 25:31-46). In most of these cases, angels are involved subject to the authority of the Son of Man.

16 . Some scholars have suggested that the parable of the weeds (Mt 13:24-30, 36-43) is a Matthean reworking of Mark's parable of the seed growing secretly (Mk 4:26-29) (cf. Davies & Allison 2004b:407). Even if the parable of the weeds is considered as a redactional revision of Mark's parable, Matthew remains unique insofar as he describes the eschatological activity of angels (Bendoraitis 2015:80).

17 . In many cases, the parables are framed by introductions (προμηθία - forethoughts) and conclusions (ἐπιμηθία - afterthoughts) that provide evaluations and interpretations. Although some of these introductions and conclusions may have formed part of an original story, others were added by the evangelists. Gerhardsson (1991:325) warns that 'modern expositors can increase their hermeneutic freedom immensely, when they cut the narrative meshalim out of their frames'.

18 . Matthew repeatedly mentions the relation between the Son of Man and angels (Mt 13:41; 16:27; 24:30).

19 . Jewish literature from the Second Temple Period reflects a growing interest in apocalyptic and celestial mysteries. This literature exhibits an increase in descriptions of heavens, its inhabitants and their activities (Bendoraitis 2015:18).

20 . Earlier in the Gospel, John the Baptist also alluded to Jesus' role as judge (Mt 3:12).

21 . Matthew refers to judgement in further instances where angels, however, are not mentioned. Nonetheless, they are implied at the conclusion of the parable of the wedding banquet (Mt 22:13), as the servants in the parable perform the same duty as the angels in the parables of Matthew 13.

22 . In Jewish traditions, the Satan is also portrayed as one with angels standing under his evil authority, for example in 2 Enoch (2 En 29:3-5) and in the Martyrdom and Ascension of Isaiah (Mart. Ascen. Is 2.2). The same idea of Satan along with his angels appears in Christian traditions, for instance in Revelation 12:7-9.

23 . In the Old Testament, signs in heaven are commonly associated with the Day of the Lord (Is 13:10; 34:4; Ezr 32:7-8; Jl 2:10, 31; 3:15) (Witherington III 2006:451).

24 . Matthew 24:15 makes this reference explicit in the phrase 'as was spoken of by the prophet Daniel'.

25 . Revelation 1:7 also connects these texts from Daniel and Zechariah.

26 . When the high priest asks Jesus about his identity, he responds 'From now on you will see the Son of Man sitting at the right hand of the Mighty One and coming on the clouds of heaven' (Mt 16:64). The irony is significant. The one who now judges Jesus will eschatologically be judged by him as Son of Man.

27 . The blowing of the trumpet probably alludes to Isaiah 27:13 and has many parallels such as those found in 1 Corinthians 15:52 and 1 Thessalonians 4:16.

28 . The Son of Man and the angels are also mentioned in Matthew 24:36 in a statement on the unexpectedness of the day of Jesus' return. It seems odd that even the Son of Man himself does not know the time of his return. However, the point is that the disciples must be prepared at all times. Even those who one would expect to know the time of his return do not know. How much less would it be possible for the disciples to know the time?

29 . In Jewish literature, the role of the eschatological judge belongs to God himself (cf. 1 En 9:4; 60:2; 62:2; 47:3; Test. Ab 14A).

30 . Following this depiction of the Son of Man in all his glory, Matthew proceeds with the passion narrative, with its seemingly contradictory depiction of the suffering of Son of Man: 'When Jesus had finished saying all these things, he said to his disciples, "As you know, the Passover is two days away - and the Son of Man will be handed over to be crucified"' (Mt 26:1-2). Matthew emphasises the glory of the Son of Man before he proceeds with the narrative of his humility.

31 . The disciple is only named in John's Gospel.

32 . In 2 Kings 6:17 Elisha shows his servant that he is not afraid of the king of Aram's forces, because 'the hills were full of horses and chariots of fire all around Elisha'. Similar depictions of protection and readiness for battle by angels are found inter alia in 2 Baruch 51:11; 55:3; 63:5; 2 Maccabees 11:6.