Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

HTS Theological Studies

versión On-line ISSN 2072-8050

versión impresa ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.76 no.3 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v76i3.5283

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Adzan Pitu? Syncretism or religious tradition: Research in Sang Cipta Rasa Cirebon mosque

Wawan HermawanI, II; Linda Eka PraditaI, II

IDoctoral Student Indonesian Language Education, Sebelas Maret University, Surakarta, Indonesia

IIFaculty of Teacher Training and Education, Majapahit Islamic University, Mojokerto, Indonesia

ABSTRACT

Adzan Pitu is one form of the legacy of Syarif Hidayatullah in spreading Islam in Cirebon. One of the ways in which Sunan Gunung Jati spread Islam is by building mosques. The construction of the Sang Cipta Rasa mosque aims to centre the spread of Islam in Cirebon and surrounding areas. A Mosque is symbolised not only as a place of worship but also as a place of studying Islam. This is what underlies the construction of the Sang Cipta Rasa mosque by Syarif Hidayatullah which is now in the Kasepuhan palace complex in Cirebon. The noble goal is constrained by the evil intentions of the Mataram envoy who wished to thwart the construction of the mosque. Until today, when the People of Cirebon are affected by an epidemic such as measles, they have to perform Adzan Pitu to repel the outbreak and sacrifices as a condition to purify the spell that was spread by the envoy of Mataram. Adzan Pitu is a call to prayer with seven people at the same time. It is a form of mixing of Islamic and Hindu culture. Adzan Pitu has character values in it, which include religious values, hard work and social care. The values contained in Adzan Pitu are a reflection of Syarif Hidayatullah's struggle in spreading Islam in Cirebon. In addition, these values are also a legacy of Sunan Gunung Jati in an effort to increase the value of character for the nation's next generation.

CONTRIBUTION: This article contributes from a multidisplinary theological perspective to hermeneutical studies behind philosophies related to the Abrahamic religions as expressed in the Qur'an.

Keywords: folklore; syncretism; character education value; Adzan Pitu, Character Values, Religious Tradition.

Introduction

Oral tradition is the cultural wealth of the local community which is now very important to be maintained in the midst of people who are familiar with technological progress. This does not rule out the possibility of forgetting traditions in the community. Therefore, comprehensive efforts are needed to maintain the traditions that exist in a society so that they can be passed on to future generations. For this reason, a study is needed in relation to the oral traditions in a society, namely, the study of folklore.

The study of folklore seeks to describe the origins of tradition, messages and meanings, and the functions of tradition that exist in the community. The aspects raised in oral literature research (folklore) include three things: (1) reviewing the origin of oral literature (folklore), which reveals where the literature was born, whether it is successful in reflecting the condition of the community and what the transformation process is; (2) reviewing the message and meaning of oral literature, namely, what symbols are used to cover the message and is it still relevant to a society; and (3) reviewing the function of oral literature, amongst others, for sociopolitical control, educating the public, satire and so on (Endraswara 2011:154-155). Folklore studies can use the tradition of the community as the object of study. The community tradition is Adzan Pitu at Sang Cipta Rasa mosque in Kasepuhan Palace, Cirebon. The tradition of Adzan Pitu is important to be studied because this tradition was announced by seven muezzins simultaneously and is the tradition that only exists in Cirebon.

The tradition of Adzan Pitu is one of the folklore that is not just living and scattered in the community but also has an important meaning. The study of folklore can be used as an appropriate means for the planting of values and norms in society that are now forgotten; furthermore, it can aid in the development of oral literature itself. Conserve traditional culture that has positive value is very necessary not only for the tradition itself, but also in the broader context of supporting national development.

In this study, we have not only examined the study of folklore but also analysed the importance and values contained in the tradition. This is because these values can be understood by listeners or readers through the stories depicted in the tradition of a community. The values examined in this study are the character value. This is an aspect of the study because the character value is a value that includes all the values that exist in everyday life and the value of Godhead.

Based on the existing literature on syncretism, it can be stated that previous research on this topic only focused on religious syncretism, architecture, the use of syncretism in school learning, culture, beliefs and semantic categories. Therefore, it can be stated that no previous research on syncretism and the value of character education in the tradition of Adzan Pitu in the Sang Cipta Rasa mosque in Cirebon has been carried out. In addition, the tradition of Adzan Pitu in the Sang Cipta Rasa mosque in Cirebon can be expressed as a novelty from previous research point of view, because in the previous study no one had examined Adzan Pitu from the perspective of syncretism and the character value simultaneously.

The theory used in this study is folklore and the value of character education. Folklore is a part of a collective culture that is spread and passed down from generation to generation, amongst any kind of collective, traditionally in a different version, both in oral and sample forms accompanied by gestures or reminders (Danandjaya 1991:2). There are three types of folklore. The first one is oral folklore.

Oral folklore defined as a pure oral folklore, actually produced orally and spoken by word of mouth, which belongs to the category of (1) folk speech, such as accent, epithet, traditional rank and title of nobility; (2) traditional expressions, such as proverbs and slogans; (3) traditional questions, such as puzzles and folk poetry, such as pantun, gurindam and syair; (4) stories of people's prose, such as myths, legends and tales; and (5) folk songs. The second type of folklore is partial oral folklore. It is a folklore whose form is a mixture of oral and not oral elements. The forms of folklore that fall into this category include (1) traditional skills, (2) folk games, (3) customs, (4) ceremonies, (5) folk theatre, (6) folk dance and (7) people's parties. The third one is non-verbal folklore. This genre is divided into two sub-groups: the folklore group, not the material and immaterial oral. The forms of non-verbal folklore material include (1) folk architecture such as traditional houses, (2) folk handicrafts such as traditional clothing and typical regional body accessories, (3) traditional food and drinks and (4) traditional medicines, whilst immaterial non-oral folklore forms include (1) traditional gesture, (2) signal sounds such as kentongan for communication and (3) folk music (Danandjaya 1991:21).

Character education defined as efforts that are systematically designed and implemented to help students understand the values of human behaviour that relate to God the Almighty, self, fellow human beings, the environment and nationality manifested in thoughts, attitudes, feelings, words and actions based on religion, laws, manners, culture and customs (Wibowo 2012:48). Character education has a higher meaning than moral education because character education is not only related to the problem of right or wrong, but how to instil habits about things that are good in life, so that children or students will have high awareness and understanding, and care and commitment to apply virtue in everyday life (Mulyasa 2012:3).

From the above opinions, it can be concluded that character education is a form of one's behaviour based on noble values and characters that are implemented in daily life, within both the family and society.

There are 18 components of character education. The first value is religious value, which includes attitudes and behaviours that are necessary for carrying out the teachings of the religion one adheres to, tolerant of the implementation of worship of other religions and living harmoniously with adherents of other religions. The second value is honesty, which includes behaviour that is based on the effort to make oneself a person who can always be trusted in words, actions and work. The third value is tolerance, which includes one's attitudes and actions that respect differences in religion, ethnicity, opinions, attitudes and actions of others who are different from them. The fourth value is discipline, which includes actions that show orderly behaviour and comply with various rules and regulations. The fifth value is hard work, which includes behaviour that shows earnest effort in overcoming various obstacles to learning and assignments, as well as completing the task as best as possible.

The sixth value is to be creative, which includes thinking and doing something to produce new ways or results from something that has been owned. The seventh value is to be independent, which includes attitudes and behaviours that are not easily dependent on others in completing tasks. The eighth value is to be democratic, which includes ways of thinking and acting that assess the rights and obligations of one's self and others. The ninth value is curiosity, which includes attitudes and actions that always strive to find out more deeply and broadly from something learnt, seen and heard. The 10th value is the spirit of nationality, which includes ways of thinking, acting and being insightful that place the interests of the nation and state above one's self and group interests.

The 11th value is love of the motherland, which includes ways of thinking and acting that show loyalty, care and high appreciation for the language, physical environment and social, cultural, economic and political. The 12th value is respecting achievements, which includes attitudes and actions that encourage one to produce something useful for the community, and acknowledge and respect the success of others.

The 13th value is to be friendly or communicative, which includes actions that show the pleasure of talking, hanging out and working with others. The 14th value is love of peace, which includes attitude, words and actions that cause others to feel happy and safe for their presence.

The 15th value is fond of reading, which includes the habit of providing time to read various texts that provide virtue to one. The 16th value is caring for the environment that includes attitudes and actions that always try to prevent damage to the surrounding natural environment and develop efforts to repair the natural damage that has occurred. The 17th value is social care, which includes attitudes and actions that always want to provide assistance to other people and communities in need. The 18th value is responsibility, which includes the attitude and behaviour of a person to carry out his duties and obligations, which one should do to himself, to the community, to the environment (natural, social and cultural), to the country and to the Almighty God (Wibowo 2012:43).

The place (setting) of this research is Sang Cipta Rasa mosque complex of Kasepuhan Palace in Cirebon. This research is a qualitative study. It uses a folklore approach to describe what a problem is and then analyses and interprets the existing data. The data of this study comprise oral data, which come from hereditary stories, namely, from the tradition of Adzan Pitu in the Sang Sipta Rasa Cirebon mosque. The data studied are related to the tradition of syncretism and character education values in the tradition of Adzan Pitu. This research used source an theory triangulation of sources and theory. Source triangulation is intended to validate data from data sources other than documents, such as the results of interviews with informants. Triangulation theory uses several theories to asses that the findings obtained are valid. The theory that is the reference for validating the findings in this study is the theory of folklore. Data collection techniques in this study involved documentation and interviews. The steps in collecting the data were as follows. The first step was to prepare a data collection sheet. The second step was recording. The third step was conducting an interview with the resource person. The last step is data reduction. Data analysis techniques used in this study are interactive techniques. The steps of data analysis techniques in this study include three components, (1) data reduction, (2) presentation of data and (3) drawing conclusions.

Syncretism of the Adzan Pitu tradition

The Adzan Pitu tradition is one of the cultural heritages in Cirebon. This tradition is one of the legacies of Syarif Hidayatullah or better known as Sunan Gunung Jati. Adzan Pitu is a call for prayer echoed by seven people simultaneously. In the beginning, Adzan Pitu was announced during prayer, but now Adzan Pitu was announced during Friday prayers.

The emergence of the Adzan Pitu tradition began when Syarif Hidayatullah or Sunan Gunung Jati started constructing a mosque which is now known as Sang Cipta Rasa mosque, which is located in the Kasepuhan palace complex in Cirebon. The construction of this mosque was intended to be a centre for preaching Islam at that time, and therefore the construction of the mosque was very important. However, the noble intention of Sunan Gunung Jati did not go smoothly, and there were pebbles when the spread of Islam was carried out on the land of Cirebon. This was evident when the construction of Sang Cipta Rasa mosque was going on; an envoy from Ancient Mataram named Megananda tried to thwart the making of the mosque. Megananda was a Hindu who hates Islam. Megananda had the magic called Menjangan Wulung. Megananda has the ability of black magic, anyone who is exposed to the teachings of wulung jokes will immediately die bleeding all over his body.

The mosque is symbolised not only as a place of worship but also as a place of learning Islam. This has become the efforts of non-Muslims to thwart the spread of Islam, which at that time was prevalent in Hinduism. One of them was carried out by Megananda with mejangan wulung with the intention of thwarting the construction of the mosque.

Megananda made an effort to silence Sang Cipta Rasa mosque secretly by going up to momolo [dome] mosque and hiding whilst waiting for the right moment to vent his hatred. When there was a muezzin coming to proclaim the call to prayer, he immediately spread the Menjangan Wulung teaching spell and immediately the muezzin sprang up with a bloodstained body. The incident kept repeating, and three muezzins had become victims. Furthermore, some students who would be praying at the near-completion mosque also became the victims of Megananda's ferocity. As a result, no one dared to approach the mosque, let alone complete the construction.

Seeing these strange events, Panembahan Ratu named Nyi Mas Kadilangu, the king in power at the time, became anxious and concerned. He summoned Sunan Gunung Jati as the leader of the Walisongo Council and asked him to stop the Menjangan Wulung teaching spell that had taken so many lives. The Walisongo were shocked to see the incident, then they deliberated to deal with a strange incident that continued to consume the victim. They agreed to appoint Sunan Kalijaga to find out and at the same time destroy the causes of the victims' fall in a terrible way. Having a heavy mandate, Sunan Kalijaga asked for time to ask Allah's instructions. Sunan Kalijaga departed to the Amparan Jati compound to give a tribute.

Seven days later, Sunan Kalijaga came to the Walisongo Council to explain the results of the trial.

He revealed that the cause of death of the muezzin and the santri is Meganada's magic power called Menjangan Wulung and that the teaching can be destroyed by proclaiming the call to prayer which is sung by seven muezzins simultaneously. However, there must be a sacrifice that is two women who are sincere and pure hearted as the key to the destruction of spells. Of course, the Walisongo Council was confused about determining who the woman was willing to be a victim. Amidst the confusion, suddenly Nyi Mas Kadilangu stated her willingness to be sacrificed followed by the willingness of Nyi Mas Pakungwati, the wife of Sunan Gunung Jati. The council became objected to the intention of the two women whom they respected so much.

However, Nyi Mas Kadilangu and Nyi Mas Pakungwati remained adamant. They wanted the mosque to be resolved immediately and become the centre of the spread of Islam. With a heavy heart, the council finally granted the wishes of the two women.

Towards dawn, Sunan Kalijaga decreed seven muezzins to immediately call the call to prayer simultaneously. When the call to prayer was finished, suddenly from the direction of Momolo the mosque sounded a tremendous explosion and the Momolo bounced away to the Great Mosque of Banten, whilst Megananda turned into a heirloom called Walung Ireng. The screams of the two women who volunteered to absorb Menjangan Wulung's teachings sacrificing their own lives for the interests of their religion and their people.

Sang Cipta Rasa great mosque has no momolo [dome], whilst the Great Mosque of Banten has two momolo. To remember the incident, on the eve of Friday prayers at the Sang Cipta Rasa great mosque, the prayer of seven muezzins was heard simultaneously.

The Adzan Pitu tradition is related to the belief in syncretism, namely, the mixing of Hindu and Islamic beliefs, the people who began to embrace Islam but were still influenced by Hindu beliefs. This can be known from worship activities which still have influence from Hindu beliefs. Considering that Hinduism entered Indonesia before Islam, especially in Cirebon, most of the people at that time still embraced Hinduism; therefore, the influence of Hindu belief was very strong when the spread of Islam happened in Cirebon.

The mosque is an Islamic symbol, whilst the mantra (which is spread by Megananda) and tumbal (Nyi Mas Kadilangu and Nyi Mas Pakungwati) constitute a magical power that is believed by Hindus. In Hindu rituals, often depicting sacrifices or sacrifices for Dewa is a sacred effort to reject reinforcements. Likewise, the sacrifices of Nyi Mas Kadilangu and Nyi Mas Pakungwati were conditions for cleaning and purifying mosques from the evil influence of Megananda. At that time there was an outbreak of measles-like diseases, it was known that at that time there was an outbreak of measles-like diseases in the Cirebon area and that included the outbreak was Nyi Mas Pakungwati who later died inside the mosque, so Megananda's story appeared.

The king must be above his people, it seems that the tradition was also held firmly by the Cirebon family of music, when building a mosque was not accompanied by momolo, the dome located above, where the muezzin echoed the call to prayer. Because when the muezzin goes up to momolo it means he is above the king, and that cannot happen, the people must still be under his king. Therefore, Momolo mosque was not built. So that the sound of the call to prayer could be heard clearly until it reached a faraway place, of course many people had to bring it together at the same time (loudspeakers did not exist at that time). However, what appeared in the community's understanding was not that philosophy, it was precisely the great story about the Black Science of Menjangan Wulung and bounced and then the flight of Momolo towards Banten then clung to the Banten mosque.

The present study findings regarding the existence of a religious syncretism in the Adzan Pitu tradition are in line with Singh's (2015) research, which discussed the syncretism of the Meitei people in Manipur, a northeastern Indian state. The results showed that the syncretism of traditional primordial religions and Hinduism gave rise to a new and unique essence for their culture and exhibited the cultural products of the aesthetic syncretism of religion (Singh 2015:21). There are similarities and differences between Singh's (2015) and the current research. The equation lies in the aspect under study, that is, syncretism. In addition, the differences between Singh's and our research are as follows: while Singh's (2015) study focused on syncretism in traditional primordial religions and Hinduism, we examined syncretism of Adzan Pitu and the character value. Therefore, the focus of the present study has advantages over that of Singh's (2015) research because our study not only focused on syncretism but also examined the value of character.

The research findings regarding syncretism in the form of Islamic and Hindu beliefs in the Adzan Pitu tradition, such as the Adzan and mosque in Islam and sacrifices and mantras in Hinduism, are in line with Ashadi's (2015) research, which aimed to determine syncretism in the form of the architecture of the Great Mosque of Demak. The results showed that syncretism in the form of Demak Great mosque architecture can be traced through the relationship of local architecture, namely, Javanese architecture (Kejawen) and Hinduism or Buddhist architecture, with foreign architecture, namely, Nabawi mosque, modern architecture and colonial architecture (Ashadi 2015:26). Ashadi's (2015) research has similarities with our research, namely syncretism. The difference between Ashadi's (2015) and our study lies in the fact that while our study focussed on syncretism of call to prayer and character values, Ashadi's research was about syncretism in the form of the architecture of the Great mosque of Demak.

Understanding of the teachings Islam as a whole in the community, especially when the spread of Islam during the Sunan Gunung Jati period in Cirebon caused an understanding or belief that had existed before Islam entered (Hinduism and Buddhism), was still felt in the process of spreading Islam carried out by Sunan Gunung Jati, such as sacrifices and spells. The results of the study are in line with such as sacrifices and spells.

This research aimed to identify the forms of syncretism practised by Christian churches in Kenya, to find out the reasons why Christians still practise syncretism in Kenya and to evaluate Christian strategies that deal with syncretic practices in churches in Kenya. Mwiti determined that preachers teach about syncretism using familiar records from the Bible, church leaders teach the supremacy of Jesus Christ and they must teach and apply salvation through grace through faith to deal with syncretic practices. Mwiti's research concluded that spiritual dissatisfaction was prevalent amongst preachers who did not meet the spiritual needs of members of the congregation, that Christians did not feel protected by the gospel and that insecurity caused Christians to become shamans (Mwiti, 2015: 42).

There are similarities between this study and that of Mwiti's in that both examined syncretism. In addition, there are also differences between these two studies. Whilst Mwiti's research focused on spiritual discontent, not feeling protected and the discomfort of Christians that caused Christians to become shamans or face syncretism, our study sought to discuss the existence of a Muslim belief regarding sacrifice and mantras caused by the construction of the Sang Cipta Rasa mosque. Furthermore, the researchers also discussed the character values contained in the Adzan Pitu tradition.

This research regarding the influence of Hindu beliefs in the process of spreading Islam and research conducted by Singh's, Ashadi's, and Mwiti's regarding the religious syncretism are in line with the study Daniel' (2012) research which sought to evaluate Christian beliefs in Kenya. Since the coming of the gospel in Africa, African Christians have not considered it very important in their lives.

Despite all missionary efforts to disregard belief in occultism and superstition as evil, this belief is a reality in the lives of many Christians in Kenya (Daniel 2012:10). There is similarity between Daniel's (2102) research and the present study, which is examining religious syncretism. The difference only lies in the fact that our study discussed syncretism in the Adzan Pitu tradition at the Sang Cipta Rasa mosque and the character values contained therein, Daniel's (2012) research focussed on Christian syncretism in Kenya.

The findings of this study regarding the influence of beliefs on other religions were also found in Umoh's (2013) study, which sought to discuss various nuances of superstitious belief and syncretism.

Superstition and syncretism have jointly infected authentic religious commitments to Christianity or Islam in Africa (Umoh 2013:32). There are similarities between research conducted by Umoh (2013) and this study: that is syncretism. The difference lies in the fact that whilst our study focussed on Hindu beliefs in Islam (sacrifices and mantras) and examined the character values contained in the tradition of Adzan Pitu, Umoh's (2013) research revealed the existence of superstitious beliefs and syncretism that resulted in religious influences in Christianity or Islam in Africa.

The influence of Hindu belief in the spread of Islam in Cirebon is clearly evident in people who still believe in the existence of mantras and sacrifices. This happens when in the midst of society there is a shift in beliefs and culture that was originally shifted from Hinduism to Islam. This is what makes a syncretism in the spread of Islam in Cirebon. This study's findings are in line with that of Makin (2016) which aimed to harmonise the practice of syncretism in local and foreign religious traditions found in texts such as Sutasoma, Kertagama, Dewa Ruci, Babad Tanah Jawa and Centini. The findings showed that since ancient Singosari and Majapahit, alignment and syncretism between many religious traditions have been carried out.

Hindu-Buddhist came first followed by Islamic works which added syncretism. The findings of this study also reveal that Hindu-Buddhist figures are retold in Islamic works, with various modifications. The story of Sunan Kalijaga reflects older sources such as Sutasoma, Ken Arok, Bima and other figures. The stories contained in these texts teach everyone about the relativity between evil and good, and that evil is not destroyed but is turned into good. Research conducted by Makin (2016:2) has both similarities and differences with the present study - similarity in the sense that both studies discuss syncretism in a religious tradition, and difference in the sense that whilst this study tried to examine syncretism in the Adzan Pitu tradition at the Sang Cipta Rasa Cirebon mosque and character values, Makin's (2016) research analysed syncretism in local and foreign religious traditions found in the texts of Sutasoma, Kertagama, Dewa Ruci, Babad Tanah Jawa and Centini.

The findings of this study relate to the influence of Hindu-Buddhist religious beliefs on the spread of Islam on the island of Java, especially in Cirebon, by Sunan Gunung Jati. This is in accordance with Salim's (2013) research which revealed that there was a belief in animistic dynamism in carrying out Islamic religion such as slametan. Slametan rituals are a common ritual performed by all Javanese. This ritual has a usurped animism and Islam that functions as a social unifier where its symbols can be interpreted (Salim 2013:259).

The present study's findings have similarities with that of Salim's (2013) research in that both discussed syncretism. There is also difference in that whilst Salim's study explored syncretism in Islamic religious rituals that are generally carried out by Javanese people, namely slametan, the present article discussed syncretism in a call to prayer and the character values contained therein.

Mixed culture or acculturation carried out by adherents of Islam is specifically a mixture of Hindu and Islamic cultures regarding beliefs, such as sacrifice and spells, that are still being carried out in Cirebon, as were during the spread of Islam by Sunan Gunung Jati. The results of this study are related to research conducted by Rukuni (2019:8), which revealed the existence of enculturation in Christian social ethnics.

There is a mutual Influence of social dynamics, religious politics and orthodoxy. The continuity of this merger results in religious politics. The results of the present study and that by Rukuni's (2019) research showed some similarity in that both discussed the existence of incorporation in beliefs or religion. The difference lies in the fact that whilst our research focussed on religious rituals, Rukuni's (2019) study focussed on cultural mix seen in social, political and religious integration.

Character value in the Adzan Pitu tradition

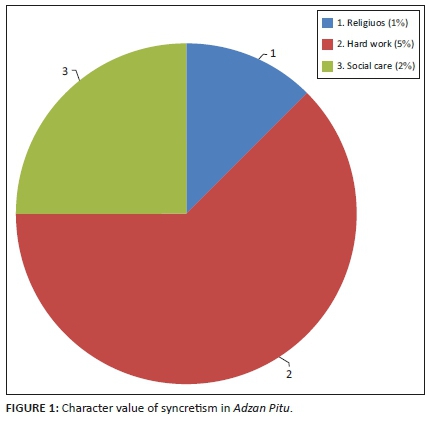

The character education values contained in the tradition of Adzan Pitu are religious, hard work and social care (see Figure 1). These values are the embodiment of a tradition of Adzan Pitu in the Sang Cipta Rasa mosque.

The value contained in the Adzan Pitu tradition is a manifestation of the cultivation of character values to the nation's next generation. This is because the Adzan Pitu tradition is still being carried out as a form of cultural preservation and cultivation of national character values.

Data in Figure 1 show that the value of the character of hard work is a value that is found in the syncretism of Adzan Pitu. Character values are rarely found or little religious values. The value of social care found in the syncretism of Adzan Pitu is a value that replaces it with the value of hard work and religious.

The first character value education is religion. Religious values are attitudes and behaviours that are necessary for carrying out the teachings of one's religion. This value was seen when the call to prayer was announced at the Sang Cipta Rasa mosque in Cirebon. Adzan is a sign of the entry of prayer times. The first spread of Islam in Cirebon by Sunan Gunung Jati was the construction of a mosque, now known as Sang Cipta Rasa mosque. One of the rituals of worship in congregation in the mosque and a marker of the entry of prayer times is to call a prayer. At that time, the call to prayer was still natural and had not been touched by technology such as loudspeakers; therefore, the call to prayer was very important in performing prayer services.

The second character education value is hard work. Hard work is a behaviour that shows serious effort in overcoming various obstacles. The value of hard work appears in the earnest efforts made by Sunan Gunung Jati assisted by Sunan Kali Jaga, Nyi Mas Kadilangu, Nyi Mas Pakungwati and the followers of Sunan Gunung Jati who were trying to stop the Menjangan Wulung, Megananda's teaching that had resulted in many deaths. These efforts were carried out by Nyi Mas Kadilangu as the king at that time by instructing Sunan Gunung Jati as the Wali Songo Council to stop the Menjangan Wulung teaching. Because of the help of Sunan Kali Jaga, finally an attempt was made to stop and destroy the Menjangan Wulung teaching by calling on the call to prayer with seven people together.. The hard work carried out by Sunan Gunung Jati along with others is a tangible manifestation of how many problems can be solved by resolving these problems or obstacles.

The third character education value is social care. Social care is an attitude and action that always wants to provide assistance to other people and communities in need. The value of social care is reflected in Nyi Mas Kadilangu and Nyi Mas Pakungwati when they proposed themselves as sacrifices. The sacrifice was one of the conditions for the Menjangan Wulung, Megananda's teaching, to be destroyed in addition to the call to prayer with seven people together. Nyi Mas Kadilangu apart from his position as queen or king at that time and Nyi Mas Kadilangu and Nyi Mas Pakungwati were willing to be sacrificed for destroying the Menjangan Wulung,. This was done because both of them wanted the problem of Sang Cipta Rasa mosque to be immediately resolved and it could be used as a centre for the spread of Islam.

Conclusion

Based on the discussion outlined about syncretism and character education values in the Adzan Pitu tradition, it can be concluded that there is syncretism in the Adzan Pitu tradition which is a mixture of Hindu and Islamic beliefs, people who started to embrace Islam but are still influenced by Hindu beliefs. This is seen in the Adzan and mosque which are Islamic symbols and mantras and sacrifices which are symbols of Hindu belief. The character education values contained in the Adzan Pitu tradition are religious values, hard work and social care. These values are a manifestation of Sunan Gunung Jati's journey in spreading Islam in Cirebon by establishing a Sang Cipta Rasa mosque. The value contained in the Adzan Pitu tradition is an effort to instil the value of character in the nation's next generation.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the Education Fund Management Institute (LPDP) of the Ministry of finance of the Republic of Indonesia for funding my doctoral studies through the BUDI-DN program.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work.

Ethical consideration

This research was approved by the research ethics council.

Funding information

This research was funded by the Education Fund Management Institute (LPDP) of the Ministry of finance of the Republic of Indonesia for funding.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

References

Ashadi, A. & Antariksa, P., 2015, 'Syncretism in architectural forms of Demak Grand Mosque', Journal of Applied Environmental and Biological Sciences 5(11), 26. [ Links ]

Danandjaya, J., 1991, Folklor Indonesia (Ilmu Gosip, Dongeng, dll), Pustaka Utama Grafiti, Jakarta. [ Links ]

Daniel, K., 2012, 'An assessment of religious syncretism: A case study in Africa', International Journal of Applied Sociology 2(3), 10. [ Links ]

Endraswara, S., 2011, Metodologi Penelitian Sastra, CAPS, Yogyakarta. [ Links ]

Makin, A., 2016, 'Unearthing Nusantara's concept of religious pluralism harmonization and syncretism in Hindu-Buddhist and Islamic classical texts', Al-Jāmi'ah: Journal of Islamic Studies 54(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.14421/ajis.2016.541.1-30 [ Links ]

Mulyasa, H.E., 2012, Manajemen Pendidikan Karakter, Bumi Aksara, Jakarta. [ Links ]

Mwiti, S.G. & Nderitu, J.W., 2015, 'Innovative Christian strategies for confronting syncretic practices in selected Methodist and Pentecostal Churches in Abogeta Division, Meru County, Kenya', International Journal of Social Science and Humanities Research 3(1), 42. [ Links ]

Rukuni, R. & Olivier, E., 2019, 'Schism, syncretism and politics: Derived and implied social model in the self-definition of early Christian orthodoxy', HTS Teologiese Studiese/Theological Studies 75(4), 1. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v75i4.5341 [ Links ]

Salim, A., 2013, 'Syncretism. Comparing Woodward's Islam in Java and Beatty's Varietties of Javanese religion', Indonesian Journal of Islam and Muslim Societies 3(2), 259. https://doi.org/10.18326/ijims.v3i2.223-266 [ Links ]

Singh, N.N., 2015, 'Religious syncretism among the Meiteis of Manipur, India', International Research Journal of Social Sciences 4(8), 21. [ Links ]

Umoh, D., 2013, 'Superstition and syncretism: Setbacks to Authentic Christian Practice in Africa', International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention 2(7), 32. [ Links ]

Wibowo, A., 2012, Pendidikan Karakter: Strategi Membangun Karakter Bangsa Berperadaban, Pustaka Pelajar, Yogyakarta. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Wawan Hermawan

wawanhermawanunim@gmail.com

Received: 12 Oct. 2018

Accepted: 29 May 2020

Published: 17 Sept. 2020