Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

HTS Theological Studies

On-line version ISSN 2072-8050

Print version ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.76 n.2 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v76i2.5666

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Transformational diaconia as educative praxis in care within the present poverty-stricken South African context

Smith F.K. Tettey; Malan Nel

Department of Practical Theology, Faculty of Theology, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

This article explores how ministerial and leadership formation could be enabled to adopt transformational diaconia in addressing poverty in South Africa, engaging in ways in which pastoral care and leadership formation can respond to the addressing of poverty. The fact that transformation aims at changing the worldviews, paradigms and approaches to life and problem solving informs the author's concept of transformational diaconia, which was proposed as an aspect of spiritual leadership capital (SLC), defined as, 'The inner virtues afforded individuals by their spirituality in formulating their leadership paradigms which contributes to social capital formation for addressing social problems'. Spiritual leadership capital is hereby argued to be a transformative spirituality that can enable an understanding and sustainable responses to poverty and other social problems. This is needed for Africa and particularly for the present day South Africa, seemingly a country with the best infrastructure in Africa; yet its poverty seems pronounced because the dregs of apartheid still lurk in the social fibre, where poor people blame rich people for their plight and vice versa. Bowers Du Toit's view that '[m]ost congregations respond to poverty by providing relief and not empowerment', re-echoes here. From a mixed-methods research, SLC is a theory recently advanced as a congregational development paradigm and a theology of poverty, which views public theology as an educative praxis that can respond to transformational needs in poverty-related contexts. The authors suggest that for a Church that is responsive to the plight of society, fresh empowerment approaches to address poverty are needed.

Keywords: Transformational diaconia; Spiritual leadership capital; Reconstructive compassion; Public theology; Pastoral care; Poverty; Educative praxis; South African context.

Introduction

In this article, the authors discuss the role of diaconia as part of the church's role in the world, particularly focused on pastoral care as an educative praxis towards the addressing of poverty in South Africa.

Transformational diaconia as an educative praxis is a perspective argued as part of the spiritual leadership capital (SLC) theory advanced in a recent doctoral thesis by Dr Smith F.K. Tettey,1 similar to but not the same as what the Lutheran World Federation described as transformative diaconia, which could further be traced to Nordstokke (ed. 2009) who presented a paper to the World Council of Churches (WCC), where it was suggested to help overcome the so-called helpers' syndromes, practices and relations that separate 'we' from 'they' (ed. Nordstokke 2009:43-44).

Spiritual leadership capital locates the pastoral praxis of transformational diaconia in missional congregational development and follows Malan Nel's view that ministries are communicative acts on God's behalf and as such its 'transformation engages and changes all who are part of it' (Nel 2018:11). The fact remains that God's people are called for engagement in the created world (Wright 2010:229). South African theologians need to decolonise their academic response to the needs of society. As Dreyer (2017) put it:

We also have to consider how we plan and implement our community service projects (with others or for others?) and our practices of academic citizenship (for example, who gets invited to do peer reviews). (p. 5)

The authors acknowledge Niemandt's (2016) article on the WCC, 'Together towards life: Mission and evangelism in changing landscapes'; the article shows an approach that states that 'mission spirituality is always transformative'. Thus the author views pastoral care in poverty-stricken contexts as a burden for public theology to address with missional spirituality. Spiritual leadership capital theory is hereby suggested as a transformative part of authentic spirituality which serves as a means of understanding and responding to poverty and other social problems.

This discussion is based on a reflection on the ongoing poverty in South Africa and how the church contributes to the improvement in people's lives. The following questions arise: how can we practise public practical theology through diaconia as an aspect of pastoral care that provides a responsive educative approach to poverty in the historically complicated South African context? How can the South African church live in the world for the sake of the world, without being of the world?

South Africa's development plan, 'vision 2030', calls for the use of resources, skills, talents and assets of all South Africans to adequately advance social justice and address historical disparities. It aims at 'facilitating the emergence of a national consciousness that supports a single national political entity, and helps to realise that goal' (National Development Planning Commission 2015:465). This implies inner transformation, because, as Buffel (2007:56) puts it, 'poverty so profoundly marks the context that one could say that the South African churches and caregivers carry out their pastoral work in a context of poverty'. Consequently, 'many pastors feel the desperation brought about by a lack of knowledge and the inability to give meaningful assistance to poverty-stricken people' (Janse Van Rensburg 2010:1).

Rationale for this discussion

Could a missional pastoral response to poverty by the church in South Africa be possible if diaconia, which fosters inner change, is taught and practised? History suggests that this is possible. As the Apostolic Church of Acts 6:1-7 epitomises an approach to diaconia to bridge the need-gap between the Hellenists and Jewish widows in the early Church, the writer believes that a strong diaconal presence in the early church saw problems and addressed them swiftly. Breed (2014:5) addressed the point that 'it must be kept in mind that the author of 1 Peter was equipping his readers to live in a world full of hardships', as he would do to us in the South African and for that matter African Church of today.

The rationale for transformational diaconia as an SLC way of educative pastoral praxis is that, diaconia being an aspect of congregational life, concentrates on service and helps. Spiritual leadership capital seeks to build people from within to address both internal and external problems. As such, it is deemed a potent paradigm shift that can address many human and social problems like poverty.

Various works in research have dealt with the role of diaconia in the missional conversation some of which are referred to here. But it seems much attention has not been given to transformational diaconia as an aspect of spirituality as regards missional congregational leadership formation. The commonest response from the Church towards poverty has been relief efforts. Relief involves '"Doing things for people" by providing assistance without addressing long-term needs or using assets found in the people or neighborhood' (ed. Rowland 2017:2). Pastoral care aims at alleviating and helping people cope with suffering, but has not addressed the issue of empowering them to overcome the causes of the pain and suffering to a great extent. This work brings forward an aspect of diaconia centred on the transformation of people served by diaconal leadership, going beyond alleviating their pain or need to transform their views and perspective towards that. This thrives on the incarnational ministry which is driven from servant leadership paradigm and 'The serving, caring, sharing and developing conduct of the leader are central in the servant leadership model' (Manala 2014:254-255). The trend of neglect of transformational focus in favour of the reactionary (relief) approach to diaconia can be traced to the type of theological education as well as the Church's public theology or orientation towards the world outside the walls of the congregation. In this way, the educative aspect of pastoral care (didache, paraclesis and diaconia fused) aims at empowering people to move from compassion consumers to producers of Christ's love as their inner lives are made resilient by the knowledge of God's truth.

This article locates a transformational perspective of diaconia as conceived using the SLC theory. The original study was conducted within the Ghanaian Pentecostal space in which the empowering of people needing relief from poverty to cultivate their spiritual abilities towards addressing their own care needs is proposed to be emphasised. In this view, poverty must be addressed in a broader light beyond philanthropy. It rests on the backdrop that congregants mostly have what it takes to face difficulties for which they seek pastoral care and compassion, but are almost oblivious of this fact. Building up local churches is a process of returning the ministry to God's people (Nel 2009a:2). In that building-up process, diaconia is being presented in this work as an aspect of the broader field of pastoral care which includes counselling, therapy and other helping activities (Magezi 2018:1).

Towards transformational diaconia to address poverty effectively

An encounter with a street beggar in Hatfield, Pretoria

One late afternoon while returning from the library to the university guest accommodation where I lodged, I was approached, as a common aspect of South African street experience, by a young man for some 'change' (coins or small cash handouts). I stopped, looked him in the eye and said to him, 'you do not belong here!' He asked, 'what do you mean?' I said, 'you do not want to be a beggar for the rest of your lifetime, do you?' Instead of a simple honest 'no' as the answer, he proceeded with reasons for being a beggar on the street. He told me that he was neglected and rejected by his family and siblings after the death of his mother when he was 25 years old. He said the whereabouts of his father were not known as he was from a single-parent home. Therefore, he had no option other than to leave home for the streets to beg.

I said to him, 'at 25 years, you were already old enough to think for yourself. You need to decide where your life takes you. You have left your life in the hands of people who are trying to live their own lives. If you stop to tell yourself, "enough of this hopelessness", you can begin to see other ways out'. After a long motivational conversation with him, including letting him recommit his life to Christ, I gave him a small amount of money and counselled him to consider going back home, get a clean shave and give a fresh start to his broken life and to allow Christ to help him do so. After making him understand the fact that no one owes him the good life he yearns to live and that he needed to create it himself, his eyes beamed with hope and he seemed to have breathed an air of relief on discovering life anew. He promised to go back home to make peace with his family. On my next visit, he was no more at that spot. I guess he had been able to carry out his new resolve.

There are numerous people and cases in South Africa whose situations are similar to that of this young man. Can the church respond appropriately to their real need? Public theology responds to matters of public concern.

The South African context

The Church in South Africa, like others elsewhere, ought to pay attention to how its Christian message affects public life - a public theology. Agbiji and Agbiji (2016:2) observed that, pastoral care as a professional discipline and practice has not received sufficient attention in development discourse. Perhaps this scant attention could be related to the narrow conception of pastoral care, limiting its practices to the ecclesial context. This can be seen particularly in the South African context where there is a fair amount of consensus that apartheid and its legacy lives and its consequences continue to impact negatively on our society (Buffel 2007:111). Cilliers (2008) notes that in responding to problems of South African society:

The unified, prophetic voice of (Reformed) churches in South Africa is absent: it is as if the church has lost its energy to protest against societal evils like poverty, corruption, crime, stigmatization, etc. (p. 16)

Magezi (2018:10) views practical theology as 'an open process of learning, unlearning and re-learning in the space of practical life where people yearn for disentanglement from colonial hangover'. This hangover affects economic policies of post-1994 South Africa; as Kgatle (2017:2) notes, '[t]hose policies have achieved some level of economic growth, yet the majority of people in South Africa still live in poverty'. Other studies show that 'a huge contingent of people living in poverty never experiences the benefits of economic growth; instead, they are facing new and ever-growing social problems' (Van Zeeland 2016:3). The biggest problem faced is a sense of loss of identity where the Afrikaners struggle with finding a new identity in post-apartheid society and the non-Afrikaners struggle with accepting this new identity (Cilliers 2008:9-11). How does the Church develop a homiletic that addresses this dilemma? It requires the church to develop new ways that build capacity and willpower to confront oneself with truth before doing so for others.

For most congregations, poverty lurks in their backyard. More seriously, a large number of people in the Church who are living in poverty is a factor going against Christ's transforming power. It seems to portray as though Christian spirituality is unable to transform people in reality. However, God's aim is to save us as a whole.

From comfort-centredness to transformational social action

The mission of the Church has always involved a 'process of teaching them to "observe all things" that Jesus commanded. Christians have assumed that this obedience would lead to the transformation of their physical, social and spiritual lives' (Pillay 2017:1). Spiritual leadership capital as a transformational tool stands on the premise that all humans have the tendency to be held captive by their homoeostasis. Poor people settle down in their poor states and are reluctant to confront their plight for want of ideas and a sense of direction. Homeostasis is the automatic tendency of the body to maintain a balance or equilibrium (Goldenberg & Goldenberg 1996:46). In that state, people adjust to circumstances without seeking to change, or push beyond the line of resistance or against the negative situation. This is similar to equilibrium SLC (discussed above). Not until the person develops a stronger inner strength beyond that point, can he or she make changes to the status quo. At this point, social needs equal the available SLC. That means a person has the emotional, intellectual and the spiritual capacity to face the challenge in question. And as such, a leader must have a personal SLC above equilibrium before he can lead with success. Stafford (2014:18) said that purpose, work and being must be integrated before leadership does not become dualistic.

A public theology

Thiemann (1991:20) described public theology as 'faith seeking to understand the relation between Christian convictions and the broader social and cultural context within which the Christian community lives'. More practically, Van Aarde (2008:1216) notes that 'public theology emerges in multifarious facets: in movies, songs, poems, novels, art, architecture, protest marches, clothing, newspaper and magazine articles'. In other words, we express what we believe in our lifestyle, in social intercourse and in the market place. By extension, spiritual perspectives inform these facets of life in tacit and silent ways.

Diaconia defined

Nel (2018) explains that:

Diaconia was a comprehensive term that denoted everything in which humans were involved in the name of God. … It [sic] is the umbrella term for all that the congregation does, for all its ministries. What we today call modes of ministry was, in the first century, simply the diakonia of the congregation. (p. 5)

In practice, the WCC (2013) describes diaconia as:

Service that makes the celebration of life possible for all. It is faith effecting change, transforming people and situations so that God's reign may be real in the lives of all people, in every here and now. (p. 108)

Stevens (1997:636) notes the Old Testament makes a stunning contribution 'pointing to the centrality of Pastoral care in making Jesus known'.

Hodge in his commentary on 2 Corinthians 8:4, notes (Hodge 2007):

The word diakonia ('ministry,' 'service') is often used in the sense of 'aid' or 'relief' (9:1, 13; Acts 6:1; 11:29). Paul had urged the Corinthians (1 Corinthians 16:1) to make collections for the poor saints. (cc8)

Nel (2009b:6) notes, the importance of the 'cared for' metaphors. 'They help us to understand that God has given us as the congregation everything we need in order to care for creation, his world'. In this vein, 'the nature of the church is no longer understood in imperial terms seeking to normalise Christianity in society' (Boshart 2010:18). The Church by mission has become God's agent for transformation. The Church through (Lutheran World Federation 2009):

Diaconia can only fulfil its call and play an active role in shaping a better future while initiating processes of transformation, when the unique giftedness, human dignity and daily experience of each person are respected. (p. 12)

In this way, people are not treated as mere objects of compassion but as agents of change who need empowerment to carry forward the needed change.

Ham (2013) suggested transformative Diaconal ministry:

[I]nvolves both comforting the victim and confronting 'the powers and principalities' (Ephesians 6:12). It must heal the victim as well as the one who victimizes. It is a radical spirituality of struggle and commitment for transformation of sinful social structures and for the liberation of their victims. (p. 6)

Transformational diaconia as this author understands it, extends beyond ending suffering and injustice. It rather seeks to build up people, to equip them so as to address the problems for which they need diaconal ministry by themselves.

Furthermore, Jesus was a transformational minister as Anderson (2011:49) observes, 'Jesus by his being the Son of the Father was a diakonos [servant] and a leitourgos [benefactor to the world]'. This fact is in agreement with Nel (2015:124) that 'Diaconia in all its forms lead to leitourgia (service to God) nourished by Christ's redemptive work'. Taking this as a point of departure, transformational diaconia is defined as a service and care aimed at the root causes of need rather than the symptoms, aimed at creating a lasting change in the recipient and society beyond temporal existential need-level compassion. Such an approach is needed as an educative pastoral approach to poverty, which is being advanced as part of the conception of the SLC theory.

Inner strength: A missional praxis in diaconal leadership and pastoral care

The role of the congregational leader in opening up individual vistas or people's potential to address their own situations is a gospel calling. Nel (2015:175) viewed the missional congregational leader as an equipper rather than an enabler. Service in the body of Christ should be geared at equipping the saints for service which edifies the body. Consequently, diaconia in this spirit aims to unravel a sufferer's inner possibilities hitherto relegated to the background for the lack of detailed self-introspection in the face of hardship. Heuser and Schawchuck (2010:30) refer to 'the inner life' of a leader as the basis of ministry, with lessons from Jesus's model of leadership. In their 16th chapter, they identify 'transformational change' as a matter of conscience rather than of force. Klenke (2007:70) also relocates the self to the centre of leadership and specifically, 'the role of the self in authentic leadership, through three identity lenses: (a) self-identity, (b) leader identity, and (c) spiritual identity'. In the conception of SLC, all the above three lenses, proceed from the spiritual authenticity of the leader or person. The spiritual permeates all three spheres as a matter of cause.

In this vein, the congregational leader as a diaconal practitioner builds bridges between the personal and social self of congregants with the mission of God driven from a person's spirituality. 'Building mutual community is about owning our own brokenness, no longer hiding or pretending, but standing alongside others experiencing God's love and his healing' (Ruddick & Eckley 2016:5).To respond to pastoral care needs of people, their spirituality must be given direction. That implies building up people with inner strength in order to sustain them in the face of life. Thus, the church's most basic operating system (heart) is missional, relational and incarnational (Sweet 2009:35).

By implying for theological education, emphasis is needed in the formation of leaders from their hearts in order to make them adequately responsive to the inner problems of people. This is important in an age where God is the last resort when people are weak and needy. Shallow Christianity practices what Van der Westhuizen (2017:147) describes, 'God is merely a "deus ex machina" brought onto the scene, "either to appear to solve insoluble problems" or to provide strength when human powers fail'.

Furthermore, our quality of life as a society has much to do with the condition of our hearts in view of Christ's ethos of neighbourliness. In Christ we become servants of one another. Dames (2017:1) agrees with Odhiambo (2012:158) that 'there is need for the enhancement of servant leadership to reconstruct pervasive poor living conditions by providing essential services to African communities in improving quality of life'. The quality of people's life starts from the quality of their spiritual states. Bosch ([1991] 2005) states:

The harsh realities of today compel us to re-conceive and reformulate the church's mission, to do this boldly and imaginatively, yet also in continuity with the best of what mission has been in the past decades and centuries. (p. 8)

A sound public theology can refocus the church towards its mission in the world.

Definition of spiritual leadership capital

Spiritual leadership capital is defined as the inbuilt advantage that moral and aesthetic devotion or spirituality forms in personalities which becomes the primary driver for formulating their leadership paradigms and approaches to problems of life in response to the ever-changing dynamics of their world. It is not limited to 'the religious' because spirituality can be found outside religiosity.

Its positive form is the substance, essence or strength of virtuous character and drive which a person cultivates from the tenets of his spirituality or faith, that builds the social capital (SC) for solving personal and social problems. In Christian congregations, it is basic to an authentic missional leadership paradigm, as it provides the inherent advantage of motivational influence which a leader (a person) exerts on his followers through the practice and application of the teachings of his faith virtues (spirituality). It is educative and transformative. This inner working virtue is what is perceived to add value to a person's leadership capability conceptualised as SLC. Woodward (2012:3) notes that 'more than a strategy, vision or plan, the unseen culture of a church powerfully shapes her ability to grow, mature and live missionally'. Spiritual leadership capital is that inner power which underlies the culture of a people.

This article does not intend to abolish the compassionate ministry of helps. It sees as the Christian's duty not only to be a proclaimer (Kerygmatic) but also a practical witness (diaconal) to the good news, and in so doing, to love neighbour and self and to be sensitive to issues in the world (Abale-Phiri 2011:247). The goal of missional leadership is 'the transformation of people and institutions to play a part in the Missio Dei, through meaningful relations and in the power of the Spirit, in God's mission' (Niemandt 2016:57). Christ's love should motivate us to move beyond simple compassionate service (diaconia) to a reconstructive motivation of people in need to wake up after receiving compassion to start putting together the broken pieces of their lives - transformational diaconia. Changed people are those who have discovered their true identity as children of God and who have recovered their true vocation as faithful and productive stewards of gifts from God for the well-being of all (Myers 1999:14). Therefore, this 'motivation should not be reduced to coercion but grow out of authentic inner commitment' (Bass & Steidlmeier 1999:186). That is authentic spirituality.

Interestingly, 'the church has struggled to balance or integrate social change and inner change. At times they over emphasised the one and at other times the other' (Bowers Du Toit 2015:np). Hirsch (2012) in his forward to Woodward's book creating missional culture, referred to the sociologist Alvin Toffler, who once observed that 'the illiterate of the future will not be those that cannot read or write. Rather, they will be those that cannot learn, unlearn and relearn'. As an educative praxis for the church, the time has come for us to unlearn stale old ways of conducting pastoral care and relearn missional transformative approaches to old and new problems in church and society. From a balanced view, diaconia is 'both an expression of what the church is by its very nature, and what is manifested in its daily life, plans and projects' (Lutheran World Federation 2009:29).

An SLC-filled person knows the right meaning to life and faces life's challenges with a constantly renewed sense of purpose. God's 'kingdom itself is a spiritual society, membership in which is absolutely impossible without a personal change of heart (Matthew 18:3)' (Oosterzee 1878:46). This change must make the practice of diaconia to transcend philanthropic compassion leading to a transformational one. Poverty is a system and we can agree with Nygaard (2017) that:

Social systems in which people live are multilayered. The system can be a macrosystem, as seen in political systems, a mesosystem as seen in institutions, or a microsystem, as seen in close relationships. People can beat the margins in one of these systems, but not necessarily in all of them. (p. 168)

Suffering and deprivations that we see are usually the effect that each system or an amalgam of these systems has on people. The people's relationship with their system determines whether they live at the margins or at the centre. Poverty has kept people at the margins of affluent societies because poor people have not been able to reconcile their reality with the world in which the affluent live. We see such interplay of affluence and poverty in South African society. The forgoing situation is partly external, yet mainly an internal problem that needs to be looked at from the inner lives of people suffering from poverty.

One goal of missional congregational development is to enable the process of building up of a Christian community which influences the congregants and the community at large in a radical way. This makes missional theology essentially a public one. Nel (2017:3) notes that, 'being transformed into a missional congregation may disturb the peace and may make "us" lose members and donors'. But that is the cost of our being Christ's disciples. This transformational influencing can be conducted by equipping people to realign their response to external and internal problems, to position them into the desired system or situation in life. Turning attention to an educative 'strategic public pastoral theology' that aims to foster both deep self-reflection and expansive global or even cosmic citizenry (Magezi 2018:2), is imperative if the South African and for that matter African Church, universities and seminaries want to develop leaders who measure up to the tasks of our day.

Spiritual leadership capital as a change agent

Spiritual leadership capital equilibrium (SLCeq) is the point at which a leader or person's faith-driven strength, skill and composure (spiritual virtue), equals a task or challenge that requires action or response. Practically, the extent of a leader's spiritual depth, mental stability, agility and courage to make the necessary moves or changes that are required for the status quo to change for the better, is depicted along the axis towards equilibrium.

By the idea of SLC, a person's spirituality inspires courage, hope and resilience. It grants him a sense of direction that must be consistently maintained to be creatively sustainable. Sternberg (2007:46) said: 'a leader who lacks creativity may get along and get others to go along. But he or she may get others to go along with inferior or stale ideas'. Spiritual leadership capital deals with this staleness because the basis on which spiritual character and leadership are formed includes unmovable stands of the individual's conviction and they are dynamic and renewable. Pastoral leadership that ignores its spiritual nature and context diminishes the ministry to a people pleasing force and the building of brick and mortar, consequently, reducing the congregation to a social gathering rather than a community of the Spirit (Akin & Pace 2017:70).

Authentic spirituality cannot get stale although religiosity may. If majority in a community have these virtues of authentic spirituality (SLC) inculcated, it informs their working norms and acts as the balancing object in the equation that makes action equal to need. Because human needs continue to expand, SLC of leaders or persons must be constantly enhanced to meet new needs that may arise. This makes SLC-informed transformation, a reformative continuum depicting a tension between need and resources or capacity to meet them.

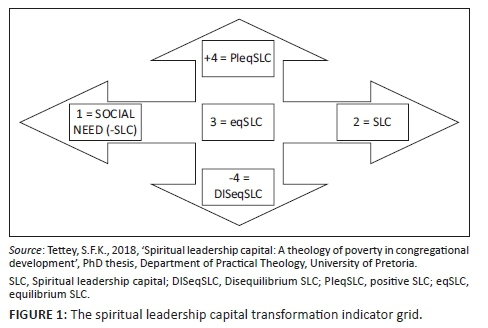

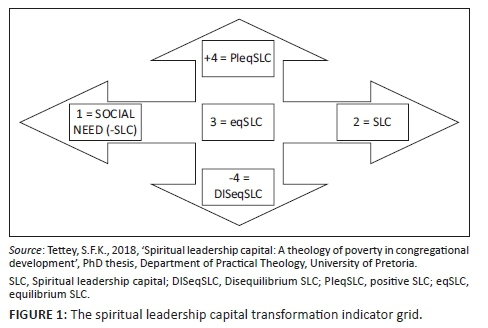

In this sense, a grid described as the SLC transformation indicator grid that portrays how people move between need and solutions as their inner states change or are transformed, is illustrated in a grid below.

The spiritual leadership capital transformation indicator grid

The SLC transformation grid (SLCTG) puts need and spiritual virtue against each other. The grid indicates whether SLC is sufficient to address needs or it falls below what is required. Hence, these two factors in tension indicate whether SLC is in equilibrium or in disequilibrium.

Figure 1 depicts the process that leads to the formation of SLC. It shows that spirituality births beliefs which in turn create personal virtues such as faith, resilience, hope, stability and faith-relevance. Consequently, these develop character which has work ethic and other habits such as creativity, will power, poise, perseverance. These good virtues enable people to solve problems and influence other spheres of life, resulting in transformation. As such, an SLC-filled Christian life and leadership becomes a transformative incarnation of Christ in the world.

Spiritual leadership capital can either be negative or positive. The negative identified as disequilibrium (DISeqSLC), occurs when people's inner capabilities produced from their spirituality comes below what is required of them to rise above the challenges they are faced with. If a particular kind of spirituality fails to transform and improve its adherents, it suggests that that spirituality is not SLC efficient. Spiritual leadership capital makes people resilient and strong against problems they face.

The opposite of DISeqSLC is positive SLC (PIeqSLC) which is simply the point which lies above equilibrium (eqSLC). Positive SLC is the point beyond eqSLC. This supposes that SLC can be under-employed or over-employed. Figure 1 shows this.

In Figure 1, the SLC grid depicts social need which is a starting point in the cycle of a typical poverty situation (point 1). The ultimate is either at +4 or −4. SLC (Point 2), which is generated in the person(s) as spirituality is adequately and authentically lived out. When equal amounts of SLC (or hypothetically, force or quantum of it) are applied to social need, that should take the situation to eqSLC (point 3 which is a coping level). At this point, people draw on inner virtues that are barely enough to meet the demands facing them.

Where a person's SLC falls below eqSLC, the situation moves towards or is at point −4 (DISeqSLC), which can be a state of poverty, social inequality, corruption or not being generally fulfilled in life or being in an adverse state. On the other hand, if the person's spirituality is SLC efficient, one is able to move beyond the need (point1) through point 3 (eqSLC) which is beyond coping to point +4 (PleqSLC) which is the point of sufficiency, fulfilment or point of satisfaction or the desired state.

A leader over-employs SLC when he spiritualises matters without reflecting purposefully and knowledgeably on the human partnership with divinity in solving problems, hence, missing out on a missional approach to such cases. Spiritual leadership capital is under-employed when a person or group ignores the spiritual element until complications set in, a stage at which it becomes more complex to reverse the damage done because the basic principles are ignored. One of the ways in which negative SLC can result is in attempting to apply human capabilities pretending that there is no need for the contribution of divinity - the case with most apophatic spiritualities.

Spiritual leadership capital as a practical theology underlying social capital formation

The calling of the church as a missional community makes it imperative for each person in the congregation to be helped to discern their situatedness in the life which Christ offers, and how the mission of God affects all human circumstances. Theology is our expression of what we perceive to be God's view of action in the world and our response towards him (Haughton 1972:228). 'The task of practical theology is to question what the undergirding epistemology and beliefs are and to reinterpret them in the light of the gospel' (Dames 2013:3). In looking at poverty from an SLC perspective, it starts from the inner state of people. The people are colonised mentally by their inability to rise above poverty.

Therefore, leaders at (Dames 2017):

[A]ll levels of society are in need of the decolonising of the mind by unlearning the current pervasive poor service ethos by relearning a new service ethic, and in learning how to maintain and sustain a progressive service ethic for the common good of all. (p. 4)

The days are long gone for society to continue on its old ways, and change is needed regarding how practical theological education is focused. Practical theology needs to expand its scope from the Church to society and everyday life or its context if new problems in our society are to be addressed. This is because, 'religious institutions which are carried by intrinsic believers, are the ones to care for and help the oppressed in society in different ways' (Dreyer 2004:919-920).

The effects of that undergirding epistemology of spirituality on a person's leadership drive and its contribution to SC formation lies in understanding SLC. Its nature grows out of the inner meaning of our relationship with our source of spiritual strength. In Christian perspective, that is a theology. In pastoral care terms, the spiritual state of a person determines how and what he can make of life in turbulent times. Thus to aim at preventing people from 'suffering for the wrong reasons', as Mathews (2002:62) suggests as the aim of pastoral care, and taking the foregoing as a point of departure, SLC posits that transformational diaconia can alleviate suffering, build up suffering people and empower them to pick up their lives afresh thus weaning them off compassion. In applying the same to a poverty-stricken South African context, the Church has a role of solidifying people in a positive and authentic spirituality which enhances life.

This takes us to Dingemans's (2002:142) view of the Church (faith community) as a 'junction where God and people, tradition and the world, challenges and reality meet'. It is 'only when a congregation's spiritual practices are focused on missional faithfulness can it be equipped for its calling to be Christ's witness in our postmodern world' (Guder 2007:125). Mission therefore, is not primarily an act of the church but 'an attribute of God' (Bosch 1991:390). In this same light, a missional Church can arrest poverty and inequality in the current post-modern, post-apartheid South Africa, if the attribute of God is inculcated in the public conscience. The need for a public practical theology that offers pastoral care holistically cannot be over emphasised.

Concluding argument

So far, the authors have tried to argue that transformational diaconia with an SLC approach, builds up people's spirituality inspires courage, hope and resilience in the congregation and society. The resulting sense of direction from this transformation empowers people living in poverty-stricken contexts like South Africa to develop resilience and take a new approach to solving their social problems. This change must be bold, honest and a complete paradigm shift. This shift should make people in the church passionate about God's mission, what Fitch (2014:1) refers to as 'being present to Christ's presence'. It requires change in and out which is called deep change.

Deep change is transformational

Change is not manipulation. It is about constant, yet responsible, reformation (Nel 2015:208, 210). In general, human and cultural change is sustainable if it begins from within. This view stands strong in the conception of SLC. Osmer (2008:177, 206) talked of deep change in identity, mission and altered operating procedures of organisations. South African society needs such a deep change similar to what Kegan and Lahey (2009:57) observe, that 'once people have identified their competing commitments and the big assumptions that sustain them, most are prepared to take some immediate actions to overcome their immunity'. It is a long-term process, which must involve thinking of change and making series of changes until the desired transformation results (Steinke 2006:79). The presence of the Church in the world has brought about many transformations. The 17th century historian, Philip Schaff, described the transformation occasioned by authentic spirituality in the apostolic era of the Church as 'practical Christianity'. He detailed this as (Schaff 1882):

The manifestation of a new life; a spiritual (as distinct from intellectual and moral) life; a supernatural (as distinct from natural) life; it is a life of holiness and peace; a life of union and communion with God the Father, the Son, and the Spirit; it is eternal life, beginning with regeneration and culminating in the resurrection. It lays hold of the inmost centre of man's personality, emancipates him from the dominion of sin, and brings him into vital union with God in Christ; from this centre it acts as a purifying, ennobling, and regulating force upon all the faculties of man-the emotions, the will, and the intellect-and transforms even the body into a temple of the Holy Spirit. (p. §44)

Steyn and Masango (2011) also note that:

Pastoral problems cannot be separated from their urge to caregivers to find solutions in the praxis of the same. Furthermore, this understanding and interpretation should also provide the caregiver with the motivational means to offer this pastoral care from within his or her theological convictions. (p. 2)

For the church to be able to transform its people who will in turn affect society, SLC posits that the educative praxis should focus on developing pastoral leaders by cultivating their inner-strengths to enable them to respond to the challenges of their world which require internal capabilities to be addressed.

Spiritual leadership capital as an educative public theological response to poverty

One presupposition which the authors go with is that of Yancey (1990:161-162), where he argues that Jesus is tilted towards the poor and this can be found in his major teachings such as the Sermon on the Mount. Jesus appears so because his gospel is one that transforms people firstly, from their heart and secondly their situation in life. The power of the Christian gospel is seen and experienced in the transformation it brings in people both ways. Therefore, every gospel activity ought to be aimed at total transformation.

Furthermore, most African pastoral care approaches tend to be informed by denominational background and practice (Magezi 2016:5). Largely, denominations carve their pneumapraxis and chritopraxis from their history and traditions. Present social contexts are also shaped in the same way, and South Africa is no exception to this. Most African Pastoral care is hindered by backward African thinking (Lartey 2013:10-20). If we have a Jesus that is separated from public discourse and is filled with a spirit that only exorcises demons but does not teach responsible living, then we cannot expect a society different from our inner states.

To transform is to improve people inside out. In this enterprise, the congregation matches its mission and salvific action with Christ's nature and purpose in society. Boshart (2010:27) calls this 'transformational witness' which is trinitarian. Nel (2017) explains that:

This divine involvement makes the congregation special - a counter community, an alternative possibility for living life in communion with the One who called and with the other called ones or many. (p. 3)

As mentioned in the introduction to this article and from a Christian spirituality viewpoint, SLC-rich leadership cultivates what Roxburgh and Romanuk (2006:27) describe as 'the practice of indwelling Scripture and discovering places for experiment and risk as people discover that the Spirit of God's life-giving future in Jesus is among them'. This creates in people 'positive chaos', which spurs them to search for answers to difficult questions, resulting in mental stability born out of a spirit filled with discernment of times and events. The transformation process is a winding long road, which does not avoid the difficult questions. It rather develops the capacity to deal with difficult situations. This hangs on the premise that our faith gives us a sense of possibilities and by this we take risks, make decisions and do our strategic thinking. Yancey (1990:21-22) notes our modern aversion to pain and suffering. Yet Christ's transformation has everything to do with scars that have healed well, failures that have been redeemed, sins that have been forgiven and thorns that have settled into the flesh. Conversion is not limited to our private or religious life. It is an all-embracing and holistic salvation (Moltmann 1993:103).

A transformed people are those who have been empowered to rise from their fall. The victory that Christ gives the saved soul is the power to live in victory over sin and its effects. Spiritual leadership capital as spiritual virtue that produces resilience in people can include what Barnes (2005:3) calls 'gravitas', 'a condition of the soul that has developed enough spiritual mass to attract other souls'. According to Barnes (2005:3), 'This "condition" makes the soul appear old, but gravitas has nothing to do with age'.

Consequently, the author contests that, most cases requiring clinical pastoral care are largely the result of people being overwhelmed by circumstances and therefore, needing help to sustain them or reduce their burdens. This can be interpreted as a leadership shortfall on the personal level. Leadership must be equal to the task facing it. In this, a leader must be strong and simultaneously humble (Nel 2015:162-164). And if leaders lack the capacity to stand problems confronting them and their organisations which they lead, they are not qualified to be leaders of that group at that stage although they might have done excellently early on. To be up to scratch in caring for souls, congregational leaders need to constantly replenish their SLC and inspire followers to build the same to confront problems facing them.

One strong public theological input that SLC can make for economic systems is its potential to enhance pastoral care which in turn contributes to the growth and expansion of human capacity which builds what others call 'human capital' an aspect of SC. 'The place occupied by religion within the category of SC comes from its value in stabilising and clarifying the purposes around which people can build their willingness to cooperate' (eds. Berger & Redding 2010:4). Development occurs as people cooperate to solve their own problems.

Spiritual leadership capital holds that a people's quality of life stems from their systems and convictions which shape their thoughts and possibilities. Spiritual leadership capital harnesses the substance of such convictions for productive living. Leaders can build it in their own lives and their followers through intentional teaching, guiding and inculturation of those basic spiritual values. In this way, the SLC-based pastoral care becomes an educative praxis.

A person stabilised from within is able to stand the external fears and threats. It is people's core beliefs, values and skills which combine to produce their leadership substance. As such, pastoral care should focus on building personal capacity of people under care rather than providing them with soft pads to rest on.

Educative implications for South African public theology

At this point, we turn to the transformational implications of a public theology that addresses poverty largely fuelled by historical trauma in South Africa. Prior to the Dutch Reformed Church becoming a state Church, a wish from Alexander Mackay (Footprints in Africa 2019), one of South Africa's mission pioneers in 1878, resounds loud as an educative praxis needed in post-apartheid South Africa today:

Men have to be taught to love God and love their neighbours, which means the uprooting of institutions that have lasted for centuries, labour made noble, the slave set free, knowledge imparted and wisdom implanted, and above all true wisdom taught which alone can elevate men from a brute to a Son of God. (p. 26)

A new public theology is imperative, more so from a complex historical backdrop which needs to be reversed. For example, Niit (2015) notes:

By the time the Afrikaner government came to power in 1948 the Dutch Reformed Church had lost contact with the original teachings of Calvyn and in doing so conveniently provided the theological foundation for apartheid. Calvyn would never have condoned the virtual deification of the nation or the absolutism of the state or of race. The Nationalists' policies led to the elevation of apartheid to a civil religion in which the secular notions of the 'volk', culture and politics became prominent features. (p. 10)

The hurts and fears from traumatic circumstances can be passed on to generations unborn if not addressed in the present. Even after over a decade of officially ending apartheid in South Africa, traditions of feeling peeved and of being left impoverished continue to affect South African society. 'Traditions are transgenerational processes by which societies reproduce themselves' (Gassman 2008:517). In the South African context, the remains of apartheid though unwanted, continue to influence the way in which most people below the poverty line perceive their situation. Beakley (2016) notes:

Poverty is a very complicated issue in Africa, and every country on the continent has its own unique challenges. One reason South Africa is even more complicated than others is that the country recently broke free from the apartheid government in 1994.

It's a country with both western influences and African influences, first world situations and third world ones, all intermingled together.

Poverty is a reality in South Africa. Yet it's not going to be resolved by just providing food. In every situation, the poor desperately need a Christian worldview and biblical understanding of the sovereignty of God. Such an understanding lifts people up. (p. 1)

Many after a decade of officially ending apartheid, continue to blame the past for their present state of poverty. This is done oblivious of the fact that South African poverty is not confined to one racial or ethnic group but cuts across all (Kgatle 2017:2). Popular opinion notes that South African society is bedevilled by continuous moral decay that now threatens the very fibre of society and needs to be redressed decisively by all South Africans (Shongwe 2017:1). And he concludes; 'it is my belief that the church is still eminently placed to influence public opinion on matters affecting the nation' (Shongwe 2017:3). This is a challenge for public practical theology, particularly pastoral care within the congregation.

Tutu (1999) writes:

Harmony, friendliness, community are great goods. Social harmony is for us the summum bonum - the greatest good. Anything that subverts or undermines this sought-after good is to be avoided like the plague. (p. 35)

The self-understanding of each individual in the social machinery is crucial for the transformation of society. Besides, cultivating a sense of belonging as a transformational process takes place through many small steps' (Sider, Olson & Unbuh 2006:157). For the South African Church, simple conciliatory, trust-building gestures can be the initial missional steps towards developing a public theology that truly meets the larger South African populace at the point of Christ's transformation.

The need for transformational diaconia cannot be overemphasised. Practical theologians in South Africa should understand that the metaphorical dregs of apartheid are still with us. Therefore, the church ought to shape leaders who can address it.

Spiritual leadership capital as a concept should therefore be explored for its usefulness to this enterprise.

Theological education should focus on a clinical pastoral care model that takes seriously, the building up of inner spiritual state of people needing care, matters of lifestyle, tradition of racial biases and how these affect the fibre of society. In terms of poverty, this article motions the church to a field beyond just almsgiving and acts of mercy, it is an invitation to the shaping of lives that are strong enough to face all that the world throws at them.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships which may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

S.F.K.T. is the main author contributing to the conceptualisation and writing up of this paper and is a research associate of M.N., the main research partner. M.N. was responsible for the monitoring of the article and offered guidance on its development.

Ethical considerations

This article followed all ethical standards for a research without direct contact with human or animal subjects.

Funding information

The research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

References

Abale-Phiri, M.H., 2011, 'Interculturalisation as transforming praxis: The case of the church of Central Africa Presbyterian Blantyre Synod Urban Ministry', DTh thesis, Stellenbosch University. [ Links ]

Agbiji, E. & Agbiji, O.M., 2016, 'Pastoral care as a resource for development in the global healthcare context: Implications for Africa's healthcare delivery system', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 72(4), a3507. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v72i4.3507 [ Links ]

Akin, D.L. & Pace, S.R., 2017, Pastoral theology: Theological foundations for who a pastor is and what he does, B&H Academic, Nashville, TN. [ Links ]

Anderson, R.S., 2011, Ministry on the fireline: A practical theology for an empowered church, Wipf & Stork, Eugene, OR. [ Links ]

Barnes, C., 2005, The law of gravitas: What makes leaders weighty, worthy, and believable?, viewed 20 October 2017, from https://www.christianitytoday.com/pastors/2005/september-online-only/cln50912.html. [ Links ]

Bass, B.M. & Steidlmeier, P., 1999, 'Ethics, character, and authentic transformational leadership behaviour', Leadership Quarterly 10(2), 181-217. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(99)00016-8 [ Links ]

Beakley, D., 2016, Poverty and the church in South Africa: An interview with Dr. David Beakley, children's hunger fund, viewed 10 January 2019, from https://childrenshungerfund.org/south-africa-poverty-christ-seminary-beakley/. [ Links ]

Berger, P.L. & Redding, G. (eds.), 2010, The hidden form of capital: Spiritual influences in societal progress, Anthem Press, London. [ Links ]

Bosch, D.J., [1991]2005, Transforming mission: Paradigm shifts in theology and mission, 12th edn., Orbis Books, Maryknoll, NY. [ Links ]

Boshart, D.W., 2010, 'Revisioning mission in Postchristendom: Story, hospitality and new humanity', The Journal of Applied Christian Leadership 4(2), 1-31. [ Links ]

Bowers du Toit, N.F., 2015, 'What has theology got to do with development?', Theology & Development, NETACT conference, Johannesburg, South Africa, January 26-30, 2015, n.p. [ Links ]

Bowers du Toit, N.F., 2017, 'Meeting the challenge of poverty and inequality? "Hindrances and helps" with regard to congregational mobilisation in South Africa', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 73(2), a3836. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v73i2.3836 [ Links ]

Breed, G., 2014, 'The diakonia of practical theology to the alienated in South Africa in the light of 1 Peter', Verbum et Ecclesia 35(1), Art. #847, 9 pages. https://doi.org/10.4102/ve.v35i1.847 [ Links ]

Buffel, O.A., 2007, 'Pastoral care in a context of poverty: A search for a pastoral care model that is contextual and liberating', PhD thesis, Department of Practical Theology, University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

Cilliers, J., 2008, 'Preaching between assimilation and separation: Perspectives on church and state in South African Society', paper presented at the Homiletics Seminar for Danish Pastors, Copenhagen, 19-20th June. [ Links ]

Dames, G.E., 2013, 'Knowing, believing, living in Africa: A practical theology perspective of the past, present and future', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 69(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v69i1.1260 [ Links ]^rND^1A01^nBernhard^sOtt^rND^1A01^nBernhard^sOtt^rND^1A01^nBernhard^sOtt

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Character education for public leadership: The continuing relevance of Martin Buber's 'Hebrew humanism'

Bernhard Ott

Department of Christian Spirituality, Church History and Missiology, Faculty of Missiology, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The need for character education for those in public leadership is of unquestionable importance. Professor Christoph Stückelberger (University of Basel, founder of Globethics) has recently argued that 'structural ethics' (constitutions, policies and standards) have their merits, and that 'there are no virtuous institutions, there are only virtuous people'. Stückelberger calls for the cultivation of virtues, especially the virtue of integrity. In recent decades, character education has received new attention. Those who call for character education most often draw from Greek traditions, especially from Aristotle. This article will explore a different source for the discussion of virtues and character. About 80 years ago, the Jewish philosopher Martin Buber proposed character education, based on what he called 'Hebrew humanism', as the foundation of nation-building. I will explore the continuing relevance of Buber's view of character and character formation, taking his famous Tel Aviv speech on 'The Education of Character' of 1939 as a point of departure.

Keywords: Public leadership; Education; Virtues and character; Character formation; Martin Buber.

Introduction: The call for character formation

Freedom, community, global justice, equality, responsibility, participation, peace, sharing, solidarity, trust, tolerance and sustainability are all values outlined in a book entitled Global Ethics for Leadership (eds. Stückelberger, Fust & Ike 2016). This book was published in 2016 by Globethics.net, a 'worldwide ethics network' with the aim 'to ensure that people in all regions of the world are empowered to reflect and act on ethical issues' (Globethics.net n.d.a:n.p.). Furthermore (Globethics.net n.d.b):

Globethics.net offers institutions the opportunity to set their ethical standards and structures to strengthen ethics not only by focusing on individual behaviour but also on institutional mechanisms used to incorporate ethics within the organization. (n.p.)

From this, it follows that special emphasis is given to senior leaders in the public sphere, in global enterprises, in non-government organisations and in higher education. The aforementioned book not only outlines core values for institutions but also identifies 'virtues in leadership', such as honesty, respect, listening, courage, vision, reliability, compassion, gratitude, modesty, patience and integrity.

Christoph Stückelberger, a Swiss reformed theologian, founder and long-time executive director of Globethics.net, contributes a chapter on integrity to the book. It is based on a speech he had delivered in December 2015 at the Protestant University of the Congo in connection with the project 'Training on Integrity in Responsible Elections' in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Stückelberger 2016c:149-165). Later he presented a slightly revised version as his farewell lecture at the Theology Department of the University of Basel (Switzerland), where he served as Professor of Ethics (Stückelberger 2016b).

I use this speech by this renowned expert in leadership and ethics in the public sphere as a point of departure because he identifies a particular, often neglected or even ignored, issue, namely, the formation of virtues and character for those in leadership responsibilities.

Stückelberger (2016b) states:

People and organisations make decisions based on motivations which derive from various factors such as power, greed, opportunities, emotions, faith - or values and virtues. Values are reference points and ethical principles on which decisions and actions are taken. They help to answer questions such as 'What shall I do? How shall I decide?' Virtues are attitudes or behaviours of individuals. Through self-control, education and regular training, an individual can become and remain an ethical person. Interpreting and giving priority to virtues over values may bring change in a person's life, as well as to a society or a culture. (p. 312)

In other words, values are external; they can stimulate or enforce ethical behaviour extrinsically. Virtues are internal; they shape a person's being so that he or she acts ethically. Stückelberger argues that we need to give priority to the formation of virtues over the definition of values. He emphasises 'structural ethics' (Stückelberger 2016b:324), but concludes that good constitutions, policies and codes of values - important though they are - remain extrinsic motivations and do not have the power to transform people.1 He argues that '[t]here are no virtuous institutions, there are only virtuous people' (Stückelberger 2016a:2). This leads him to his urgent call for the formation of virtues and character.

Stückelberger's call is not new. Throughout the centuries, philosophers and theologians have pointed to the foundational significance of character formation. In this study, I turn to the Jewish philosopher Martin Buber (1878-1965) and his remarkable contribution to education. I am convinced that his insights into the formation of human beings are of timeless significance.

In 1938, Buber was forced to leave Germany and he moved to Palestine in order to contribute to the establishment of a Jewish nation. In this context, he gave his remarkable speech on 'The education of character' (Buber 1947d:104-117). Buber was deeply convinced that the Jewish nation could never be built solely on a piece of land, on national ideas, on political structures and on military power, but ultimately only on character formation rooted in the Jewish faith. It was this conviction that distinguished him already at the beginning of the 20th century from Theodor Herzl and the nationalist Zionist movement (Buber 2002a, 2002b, 2002e; cf. Kohn 1961:40-47; Kuschel 2015:56-60).

This lecture by Martin Buber on the formation of character in the context of nation-building caught my attention many years ago. It was something like an invitation to look more carefully into Buber's writings, searching for a deeper understanding of his contribution to character formation.

This leads to the question to be dealt with in this article: what are the potential and the continuing relevance of Buber's view of character and character formation for today, especially in relation to public leadership and nation-building? After a short introduction to Buber's life and work, I will identify several key components of his contribution to the formation of character. At the end, I will challenge recent developments in higher education in light of Buber's call to character education.

The framework of Hebrew humanism

The intention and the significance of Buber's Tel-Aviv lecture of 1939 can only be captured if we first introduce the concept of 'Hebrew humanism'. Buber points out that he used the term 'Hebrew humanism' already in 1913 (Buber 2002d:158). Later, in 1933 - still living in Germany - Buber addressed the young generation of Jews confronted with National Socialism when he delivered a speech titled 'Biblical humanism' (Buber 2002c). And in 1941, at that time already living in Palestine, he spoke explicitly on the topic of Hebrew humanism (Buber 2002d). Finally, when Buber received the Erasmus Prize 1963 in Amsterdam, he titled his speech of thanks as 'Believing humanism' (Buber 1967). The three terms may not carry exactly the same meaning, but they all point to a foundational frame of reference of Buber's thinking (cf. Volkmann 2005).

By using the term 'humanism', Buber positions himself within the European discourse on renaissance, enlightenment and humanism. At the same time, the qualifying adjectives 'biblical', 'Hebrew' and 'believing' put his worldview in critical distance from all forms of anthropocentric post-enlightenment humanism. In contrast to European humanism, Buber is not referring back to the classical Greek and Roman antiquity, but rather to the ancient writings of the Hebrew Bible (Volkmann 2005:181-182).

In his 1933 speech, he defines 'Biblical humanism' as follows (Buber 2002c):

Biblical humanism is concerned with a 'concrete transformation' of our total - and not alone our inner - lives. This concrete transformation can only follow upon a rebirth of the normative primal forces that distinguish right from wrong, true from false, and to which life submits itself. The primal forces are transmitted to us in the word - the biblical word. (p. 47)

And in his address of 1941 on 'Hebrew humanism', he looks back and comments (Buber 2002d):

When Adolf Hitler stepped into power in Germany, and I was faced with the task of strengthening the spirituality of our youth to bear up against his nonspirituality, I called the speech in which I developed my program, 'Biblical humanism', to make the first half of my concept still clearer. The tide indicated that in this task of ours, the Bible - the great document of our own antiquity - must be assigned the decisive role that in European humanism was played by the writings of classical antiquity. (p. 159)

This provides a frame of reference for all of Buber's philosophical and educational writings. He moves beyond unworldly and even escapist piety, on the one hand, and a godless, purely immanent humanisation, on the other hand. His pedagogy was characterised by putting humans in relationship to the world and to God (Ventur 2003:199-208). This is summarised in some of Buber's key statements, such as 'God wishes man whom He has created to become man in the truest sense of the word' (Buber 2002d:164; cf. Ventur 2003:197).

Over against European humanism, which refers to Greek and Roman antiquity as a resource for renewal and renaissance, Buber points to the more holistic anthropology of the Hebrew tradition. He states (Buber 2002d):

[We] must reach for a farther goal than European humanism. The concrete transformation of our whole inner life is not sufficient for us. We must strive for nothing less than the concrete transformation of our life as a whole. The process of transforming our inner lives must be expressed in the transformation of our outer life - of the life of the individual as well as that of the community. (p. 161)

Buber argues that European humanism focuses too much on the transformation of the mind, the intellect, the inner life. In contrast, Hebrew humanism views humans in their totality, including the mind and body, thinking and acting.

From this point of view, he also criticised the separation of the private and the public sphere, which he observed in many societies - not least in the political programme of Jewish Zionism in his time. From the point of view of Hebrew humanism, he argues (Buber 2002d):

What it [Hebrew humanism] does have to tell us, and what no other voice in the world can teach us with such simple power, is that there is truth and there are lies and that human life cannot persist or have meaning save in the decision on behalf of truth and against lies; that there is right and wrong and that the salvation of man depends on choosing what is right and rejecting what is wrong; and that it spells the destruction of our existence to divide our life up into areas in which the discrimination between truth and lies and right and wrong holds, and others in which it does not hold, so that in private life, for example, we feel obligated to be truthful but can permit ourselves lies in public, or that we act justly in man-to-man relationships but can and even should practice injustice in national relationships. (p. 161)

For Buber, the Hebrew faith is not a religion for the inner life, the spiritual sphere in a compartmentalised world. It is a way of life rooted in the truth revealed by God in the Bible, a way of life that comprises the entire life and affects all spheres of life, individual and communal, private and public. This is the reason why the formation of character became so central in Buber's educational engagement. This leads us to his lectures on education.

The education of character

Buber began his lecture on 'The education of character' with the following statement (Buber 1947d):

Education worthy of the name is essentially education of character. For the genuine educator does not merely consider individual functions of his pupil, as one intending to teach him only to know or to be capable of certain definite things; but his concern is always the person as a whole, both in the actuality in which he lives before you now and in his possibilities, what he can become. (p. 104)

Education that only focusses on 'individual functions' of the person, on knowledge or skills, is - according to Buber - not worthy to be called education. Genuine education views the 'person as a whole' and focuses on his or her entire being; it 'is essentially education of character'.

For Buber, character is what an individual is - far beyond what he or she knows (knowledge) and what he or she does (skills). Out of a person's very being flow his or her 'actions and attitudes' (Buber 1947d:104). Buber does not use the term 'integrity' but this is what he is actually speaking about: the congruence of being, speaking and doing.

More precisely, he defines character with two terms 'actuality' and 'possibilities', or in other words, 'reality' and 'potentiality' (Buber 1947d:104). As we will see later, these are two foundational concepts in Buber's definition of character. The first term ('actuality' or 'reality') refers to a person's ability and willingness to perceive and accept his or her actual reality in the here-and-now of his or her life. The second concept ('possibilities' or 'potentiality') focuses on a person's responsibility to realise life according to his or her potential and the demands of the situation. Buber speaks about the 'personal responsibility for life and world' and 'the courage to shoulder life' (Buber 1947d:115).

This leads to the term 'responsibility', another key concept in Buber's understanding of character. By relating the term 'responsibility' to 'response', Buber gets at the heart of his understanding of responsibility. He says, '[a]n individual's responsibility exists only where there is real responding' (Buber 1947a:16), and in another speech on education, he says (Buber 1947c):

The fragile life between birth and death can nevertheless be a fulfilment - if it is a dialogue. In our life and experience we are addressed; by thought and speech and action, by producing and by influencing we are able to answer [or 'respond']. For the most part we do not listen to the address, or we break into it with chatter. But if the word comes to us and the answer [or 'response'] proceeds from us then human life exists, though brokenly, in the world. The kindling of the response in that 'spark' of the soul, the blazing up of the response, which occurs time and again, to the unexpectedly approaching speech, we term responsibility. (p. 92)

For Buber, 'responding' is an essential dimension of true human existence. Therefore, he emphasises the significance of 'responsibility' (in the literal sense of the term) for the realisation of true humanity. Character means that a person perceives reality as a call and that he or she responds in a 'responsible' way.

One of the most passionate and challenging definitions of education and the role of the educator can be found in 'Education and world-view'. Buber (1957) states:

The education I mean is a guiding toward reality and realization. That man alone is qualified to teach who knows how to distinguish between appearance and reality, between seeming realization and genuine realization, who rejects appearance and chooses and grasps reality. (p. 105)

Again, reality and realisation are at the heart of the educational goal. However, now Buber sharpens his argument by pointing to the difference between appearance and reality, between pretended realities and real realities. Persons with character are educated to distinguish between pretence and reality - and to choose reality. In 'Elements of the interhuman', Buber deals with the same issue under the title 'Being and Seeming', arguing that a mature person recognises his or her pretensions ('what one wishes to seem') and accepts and reveals what he or she 'really is' (Buber 1982:339). This again is a dimension of integrity.

In all of this, we have to take note that reality and realisation, response and responsibility have two dimensions in Buber's thinking: human beings have to respond to the realities of this world and they have to act in a responsible way (this is what Buber calls 'realisation'). However, reality should not be limited to the scope of what science (empirical reality) and philosophy (cognitive reality) can offer; it needs to be open to the transcendent (and yet immanent) reality of God.

Buber concludes his Tel-Aviv lecture with the statement (Buber 1947d:117), '[t]he educator who helps to bring man back to his own unity will help to put him again face to face with God'.

It is evident that for Buber becoming truly human includes the oneness of the person (integrity) 'face to face' with God. The relationship with the world and the relationship with God are fully intertwined. As we will see later in his essay 'The way of man', responding to the voice of God and responding to the demands of earthly realities constitute a holistic and character-forming education.

This has significant implications for the education of character. Buber argues that it is the educator's task to help individuals to a 'rebirth of personal unity, unity of being, unity of action - unity of being, life and action together' (Buber 1947d:116). As mentioned earlier, he adds at the end of his lecture on character education that, in order to reach this 'rebirth', a person needs to be put 'face to face with God'.

Furthermore, he argues that it is not sufficient to 'talk about' virtues and character in a distant and theoretical way (in Buber's terms I-It-talk). It does not help to explain what good and bad is because such cognitive knowledge does not necessarily shape character (Buber 1947d:105-106; cf. Ventur 2003:170). The educator has to 'address' the learner in such a way that a response is provoked (I-Thou-talk) - ultimately a response in the form of action, of appropriate realisation - in proper relation to God and his world. This, according to Buber, is only possible in an 'atmosphere of confidence' (Buber 1947d:107). In other words, character education requires person-to-person relationships.

In his essays 'The way of man' (1948/1964) and 'Elements of the interhuman' (1953/1982), Buber further develops the framework for a pedagogy that facilitates character formation.

The way of man

Buber understands human existence as a journey towards full humanity. This implies that life must be conducted, shaped and formed. In 'The Way of Man' (1964), Buber outlines this life-shaping journey in six steps:

1. Heart-searching: the journey begins with a person being addressed by God ('Where are you, Adam?'). We have to respond to three foundational questions: 'consider three things. Know whence you came, whither you are going, and to whom you will have to render accounts'.

2. The particular way: we should not copy others but find and realise our personal calling.

3. Resolution: we need to unify our soul - body and spirit - so that we think and act purposefully, firmly and congruently.

4. Begin with oneself: we should not blame others if it is our responsibility to take the first step.

5. Avoid preoccupation with oneself: we should not remain focused on ourselves but approach the needs of the world in the realm of our responsibility.

6. Here where one stands: it is our responsibility to realise our personal calling here and now, at the place where we are. We should not always escape into day-dreaming about other, perhaps better places to realise life.

In this essay, Buber did not explicitly talk about character formation. Nevertheless, his reflections point to the heart of the education of character in the framework of Hebrew humanism. Again, the journey towards the realisation of true human existence begins with the encounter of the eternal Thou - with responding to the 'voice' of the creator. And again, the journey towards full humanity is a journey towards greater integrity, facing the realities of one's personal life and of the surrounding world, and responding with one's entire being to the demands of the situation in a responsible way.

However, how can such a character be formed? The most specific pedagogical suggestion we can find in Buber's writing is connected to the term 'dialogue'.

Genuine dialogue

Buber is a storyteller and we best approach his pedagogical teachings by listening to one of his examples in 'On the education of character' (Buber 1947d):

The teacher who is for the first time approached by a boy with somewhat defiant bearing, but with trembling hands, visibly opened-up and fired by a daring hope, who asks him what is the right thing in a certain situation - for instance, whether in learning that a friend has betrayed a secret entrusted to him one should call him to account or be content with entrusting no more secrets to him - the teacher to whom this happens realizes that this is the moment to make the first conscious step towards education of character; he has to answer, to answer under a responsibility, to give an answer which will probably lead beyond the alternatives of the question by showing a third possibility which is the right one. To dictate what is good and evil in general is not his business. His business is to answer a concrete question, to answer what is right and wrong in a given situation. This, as I have said, can only happen in an atmosphere of confidence. Confidence, of course, is not won by the strenuous endeavour to win it, but by direct and ingenuous participation in the life of the people one is dealing with - in this case in the life of one's pupils - and by assuming the responsibility which arises from such participation. It is not the educational intention, but it is the meeting which is educationally fruitful. A soul suffering from the contradictions of the world of human society, and of its own physical existence, approaches me with a question. By trying to answer it to the best of my knowledge and conscience, I help it to become a character that actively overcomes the contradictions. (pp. 106-107)

From all we have seen so far it follows that the 'interhuman' - what happens between persons - is central in Buber's anthropology and pedagogy. Buber calls it 'the between'. In his address 'Elements of the interhuman', he identifies five aspects (Buber 1982):

1, The 'social' and the 'interhuman' should not be confused: the 'social' refers to all sorts of communal realities in which the individual can remain isolated and I-It relations may dominate. The 'interhuman' refers exclusively to what Buber calls I-Thou relationships.