Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

HTS Theological Studies

On-line version ISSN 2072-8050

Print version ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.75 n.4 Pretoria 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v75i4.5514

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Towards defining the Christian development organisation

Deborah M. Hancox

Discipline Group Practical Theology and Missiology, Faculty of Theology, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Around the world, there exist many organisations who claim a Christian motivation and whose work falls within the scope of the development sector. These organisations are distinctly different from local congregations, and whilst development as a field of theological study is becoming increasingly well-defined and established, there has been limited theological research and reflection on these organisations. Much about them remains unstudied and unclear, raising questions about their purpose, legitimacy and theological contribution. This in turn hampers a responsive and responsible engagement with them within the academy. Contributing to this oversight is the absence of an appropriate, commonly shared name and definition around which research and discourse can occur. This article reviews names and definitions currently being used and then proposes the name 'Christian developmental organisation' (CDO). It provides a rich definition, considering the CDO's organisational, societal, purpose, activity and faith dimensions. In addition, the history dimension brings an understanding of the origins and formation of the CDO whilst the relationship dimension positions the CDO within a web of relational dynamics. It is hoped that the name and definition offered in this article will promote research and engagement with the CDO as well as aid their self-understanding.

Keywords: Christian development organisation; faith-based organisation; Religion and development; Theology and development; Mission.

Introduction

Around the world, there exist many organisations who claim a Christian motivation and whose work falls within the scope of the development sector. These organisations are distinctly different from local congregations, and whilst development as a field of theological study is becoming increasingly well-defined and established, there has been very limited theological research and reflection on these organisations.1 Much about them remains unstudied and unclear raising questions about their purpose, legitimacy and theological contribution. This in turn hampers a responsive and responsible engagement with them within the academy. Contributing to this oversight is the absence of an appropriate, commonly shared name and definition around which research and discourse can occur. Most frequently they are referred to as faith-based organisations (FBOs), but, as will be discussed, this term is highly problematic.

Swart (2008) speaks to why it is important to engage these organisations within practical theology:

Our focus has gradually widened beyond a conventional ecclesiastical focus to include the wider Christian faith-based sector. That is, so-called 'faith-based organizations' should be regarded as of important strategic relevance for any future practical theological reflection, given their close association with the churches and potential to enhance an effective and specialized Christian response to the problem of poverty. (p. 147)

In addition, development itself has undergone a 'religious turn' (Jones & Juul Petersen 2011:1292-1294) and is engaging these organisations. In order to participate in this impetus for secular-religious collaboration, theologians, and especially missiologists, must 'get in the game' (Myers 2015:6). The use of a commonly accepted name and definition for organisations doing development from a Christian motivation will greatly assist in this task. This article reviews names used in both 'religion and development' and 'theology and development' literature and proposes 'Christian development organisation' (CDO) as the most suitable name. A rich definition is then given, presenting various dimensions to further help in the identification and understanding of these organisations.2

In search of a name

Religion and development literature

In development literature, the term faith-based organisation (FBO) has become pervasive for any organisation seen to be sectarian in nature and therefore much of the literature about organisations motivated by their Christian faith is to be found in the FBO discourse (Clarke 2011:15; James 2009). The term is derived from the recognition of religion and religious organisations as both a help and a hinderance in achieving development outcomes (Clarke 2011:1-24; see also Cochrane 2016; Deneulin & Rakodi 2011:52; Rakodi 2012a:640-643; Ter Haar & Ellis 2006). Whilst organisations with religious affiliations working to improve human well-being are no new phenomenon, the term FBO is relatively new. It has politically and ideologically contentious origins with its formulation necessitated by the neo-liberal economic analysis and implementation starting in the 1980s. This led to the search for alternative welfare service providers and implementers of development policy to counter-balance reduction in state mechanisms both domestically and internationally, leading to growth in secular and faith-based development non-government organisations (NGOs) (Clarke 2006:837; Manji & O'Coill 2002:577; Occhipinti 2015:332; Tomalin 2012). Alongside this motivation for the term FBO, and from a different ideological perspective, was the general increase in attention on development NGOs resulting from the growth in people-centred and alternative development approaches. This dual engagement contributed to the turn to religion in development studies since the 2000s and the term FBO was taken into common parlance across the ideological spectrum of development (Jones & Juul Petersen 2011:1292-1294; see Clarke 2006:836).

Despite its widespread acceptance, writers within the religion and development discourse agree that the term FBO is highly problematic and 'may conceal more than it reveals', causing problems for those seeking to research these organisations (James 2011:6; see Jones & Juul Petersen 2011:1298). Four problems bear mentioning. Firstly, the term FBO perpetuates an artificial dualism between organisations with a religious affiliation and those without a 'world religion' affiliation whilst in reality all organisations operate (consciously or otherwise) according to a belief system, for example, secularism. Additionally, in the majority world there is often no clear separation between the secular and sacred, making the distinctions inherent in the term FBO meaningless and unworkable (Occhipinti 2015:331; Tomalin 2012:694). Secondly, the FBO classification tends to overlook significant differences in the belief systems of religions and focuses primarily on similarities from a sociology of religion perspective (Clarke 2011:14; James 2009). Thirdly, very weak distinctions are made between the significantly different organisational types grouped together as FBOs3 (Clarke 2011:15-19; Jeavons 2003:27; Jones & Juul Petersen 2011:1298). Fourthly, the term does not allow for research and reflection on the complexity and the particularity within the development and religion nexus but encourages and enables an 'instrumentalist interest' in the positive role of religious organisations from the perspective of donor-funded development efforts (Jones & Juul Petersen 2011:1297).

As a result of these and other limitations associated with the term FBO, attempts at clarity have led to the creation of various classifications or typologies. In defining the scope for the typologies, some (for example, Jeavons 2003) include only organisations involved in development activities and provision of social services, whilst others (see Clarke 2006; Occhipinti 2015; Thaut 2009) include in their scope any type of civil society organisation (CSO) that impacts human flourishing and has a world religion connection, for example, congregations and mission organisations.

Typologies variously engage at least four dimensions of FBOs. Firstly, there are typologies (Clarke 2006; Jeavons 1997; Sider & Unruh 2004; see also Adkins, Occhipinti & Hefferan 2010:1-27) that identify religious or faith characteristics and apply levels of religiosity across different dimensions of an organisation and its programmes. The usefulness of such approaches, which seek a religious litmus test, seems to be in engaging policy, assessing the effectiveness of FBOs in development and meeting donor funding criteria (Clarke 2006; Occhipinti 2015:332). The purpose in establishing these typologies is not a theological one. Secondly, some developers of typologies such as Clarke (2006:840) rightly find it important to distinguish different organisational types within the 'complex world of faith-based organisations' and identifies five types of FBOs, based predominantly on the primary focus of their activities. Occhipinti (2015:340) builds on this approach to suggest a third means of classification, namely by type of activity, seeking to overcome the overlap that in practice exists between many organisations. A final dimension that is emerging as noteworthy is that of 'degree of formality and relationships with other faith and non-faith structures' (Occhipinti 2015:341) which takes seriously the diversity and relational complexity present within the category of FBO. Although useful, these classifications and typologies have not resolved the terminological and definitional issues resulting from the diversity encompassed in the term FBO. As a result, some commentators (see Deneulin & Rakodi 2011) favour a contextual and hermeneutic approach to understanding FBOs within development.

In addition to the variable way of understanding the term FBO, writers in the field of religion and development create their own terms or draw from others in common usage, effectively sub-typing and nuancing the FBO to suit their particular research needs and context.4 However, no single name has emerged from the religion and development discourse that is well defined and fit for purpose for theological research of organisations involved in development activities and motivated by their (Christian) faith. For example, when referring to organisations such as these, Berger (2003) uses the term 'religious nongovernmental organizations' and James (2009), within one article, uses the terms 'Christian NGO', 'para-church Christian development agencies' and 'Christian FBO'. Thaut (2009) in one article uses the terms 'Christian aid agencies', 'Christian faith-based agencies', 'Christian faith-based humanitarian agencies' and 'Christian humanitarian agencies'. Rakodi (2012b) talks about 'FBOs that resemble NGOs' whilst Burchardt (2013) uses the terms 'Christian organizations', 'Christian NGOs', 'FBOs as emergent from NGOs'. Freeman (2018) writes about 'religious development NGOs', 'evangelical development NGOs', 'church development wings' and 'on the ground Christian development agencies'. In a final example, and pointing in the direction proposed in this article, Bartelink (2016:28) speaks of the need to identify specifically Christian organisations for her research purposes in view of 'understanding the Christian identity of a development organization as something that needs to be deconstructed and analysed'. She specifically avoids using the term faith-based organization and settles on the term 'Christian development organization' (Bartelink 2016:23).

Whilst the term FBO within the religion and development discourse is still an overcrowded category, which is variably defined and sub-typed, the work carried out in seeking greater classification and definition provides a strong starting point in identifying and locating Christian organisations involved in development.

Theology and development literature

Within recent literature by theology and development writers, there is also no commonly accepted means of referring to organisations doing development based on their Christian faith. They generally reflect the widely held view, expressed above, that the term FBO is problematic but like those positioned in religion and development, they continue to use and seek to define the term (see, for example, Bowers Du Toit 2017:1). Their interest in entities encompassed in the term FBO is in relation to the key topics within the theology and development discourse.5 However, a key concern for these writers is to distinguish the local congregation from the more NGO-like Christian organisations involved in development.6 In addition, one finds classifications based on the Christian stream or confessional identity ascribed to organisations for example, Evangelical, Catholic or Pentecostal.

'Theology and development' writers in countries with a history of funding and driving programmatic faith-based development work use a variety of terms. Foremost amongst these writers who would be considered evangelical is Myers, who in his influential book, Walking with the Poor, hardly addresses the organisational unit, with only occasional reference to the 'Christian development agency' (Myers 1999:7) and the 'Christian relief and development nongovernmental agency' (Myers 1999:1), preferring to focus on the 'holistic practitioners' (Myers 1999:150) - the individuals doing the development work. In other writing he uses the terms 'Christian NGOs', 'faith-based NGOs' and 'faith-based organisations' (Myers, Whaites & Wilkinson 2000), later adding to this the terms 'Christian development NGOs' and 'Evangelical development agencies' (Myers 2015). Sugden (2010:31-36) uses the terms 'Christian development agencies' and 'Evangelical development agencies' whilst another evangelical (Samuel 2010:128-136) talks about 'Evangelical relief and development agencies', 'organisations' and 'Evangelical agencies'.

Moving to the ecumenical theology and development discourse as represented within the World Council of Churches (WCC), different terms are again used, reflecting different structures and emphases found in conciliar churches. The discourse within the WCC is dominated by diaconal discussions which, whilst related to development, are in many ways different as they seek to bring together diaconia and development (for example, in international diaconia and transformational diaconia). Taking the document 'Ecumenical Conversations' (World Council of Churches 2014) as an example, what becomes clear is the desire to dialogue around the concept of Christian witness, with the church as the primary focus, and not around development and related non-congregational organisations. Terms found include 'WCC related development organisations'; 'national level churches and organizations'; 'churches and other organizations' and 'Christian development agencies/special ministries'. There appears to be an apparent desire to avoid terminology associated with both the religion and development and the theology and development discourses or to any use of FBO-type constructs, and to avoid distinguishing between faith- and non-faith-based organisations.

Within the South African theology and development discourse, one finds more consistency in terminology, but still no single term emerges as well-defined and ready to be used in theological research. Steve De Gruchy (in Haddad 2015) does not specifically deal with definitional issues related to the FBO, reflecting perhaps a more holistic approach to the Christian faith community and an avoidance of dualism between the sacred and profane. As he was especially concerned in his research with matters of development ethics, subject matter and policy, he does not focus much on the implementing and organisational level. However, De Gruchy (2015:113) does use comfortably and with minimal definition the term 'Christian NGO'. Bowers du Toit (2017:1) clarifies her usage of the term FBO before discussing congregational mobilisation in relation to poverty and inequality. Whilst recognising the complexities in the use of the term FBO, she explicitly excludes congregations from her definition, reserving that term for faith-based development organisations. Swart (2008:144), in highlighting the practical theological concern with the problem of poverty, refers to 'churches and faith-based organizations'. However, in other places he conflates the local congregation with the CDO, talking about 'churches and other faith-based organisations' (Swart 2010:447, [author's added emphasis]), using the term here in a more general sense. Haddad (2016), like Swart, talks about 'church and faith-based organisations' while also broadening her scope of interest when she talks about 'people of faith working in the field of development either in NGOs or within national church structures'. It seems fair to say that within the South African theology and development discourse, the primary concern is the role of the church in social justice and poverty alleviation and that minimal attention has been paid to other types of Christian organisations engaged in development activities.

The review of literature shows that writers variably name and define religious organisations active in development. It is helpful to remember that these names do not arise, nor do they exist, in a vacuum but within discourses that seek to name and position the various actors within development and religion. Names also reflect contextual differences related to history and policy frameworks and are no doubt also influenced by the ideological and religious positions of the writers themselves. Despite all these factors, a fair conclusion to draw from the literature is that there is no name that is in common use that is suitable to accurately identify organisations doing development work from a Christian faith motivation.

A proposed definition of the Christian development organisation

What is required is a name and definition that enables concrete identification, sampling and theological reflection on organisations who claim a Christian motivation and whose work falls within the scope of the development sector. The definitional confusion of names such as FBO render them unusable and allows work in religion and development to be 'instrumental, narrow and normative' (Jones & Juul Petersen 2011:1291; see Rakodi 2012b:623) and theological research to be vague. Any name and definition must be specific enough to avoid the reductionism and imprecision in some names in common usage, most notably FBO,7 and yet general enough to accommodate the diversity found amongst these organisations. At the same time, excessive specificity which would result in conceptual fragmentation and unnecessary differentiation, for example, a name such as 'Evangelical Christian relief and development agency' should be avoided.8 In addition, given the global and local nature of both development and the Christian faith, a name and definition is sought that can be applied in any context. It must also have resonance with people in the organisations themselves and reflect the commonsense understanding of these organisations. With these factors in mind, the name Christian development organisation (CDO) is proposed, defined as 'a civil society organisation that exists to promote human well-being through development activities, guided by its understanding and application of the Christian faith'.9 The different dimensions inherent in this definition of the CDO will now be discussed. These are their societal and organisational positioning, their purpose, types of activities, faith character and the importance of mission and development history as well as partnerships.

Societal and organisational dimensions

At its most fundamental level, the CDO is an organisation, which may be defined as 'an organised group of people with a particular purpose' (Oxford English Dictionary 2019). More than this, though, it carries the connotation of an entity that is formally constituted and expects to have an ongoing existence. A useful way of understanding an organisation is as a system, where inputs are transformed through various processes to deliver outputs.10 Furthermore, organisations are social entities linked to an external environment. As an open and living system, an organisation is influenced by and influences its environment (Daft 2004:11).

In terms of its societal location, the CDO is positioned as a CSO. Society is widely seen as comprising the three areas of state, the markets and civil society. Civil society is multi-layered and complex with analysts using different definitions and orientations; however, it may be broadly defined as 'a sphere of ideas, values, institutions, organisations, networks, and individuals located between family, the state and the market' (Anheier 2005:57-58; Beyers 2011:3).11 Highly diverse, self-regulating, self-correcting and self-organising, civil society embraces notions of citizenship, public participation, voluntarism and civic mindedness. Importantly, it is also a dynamic domain from which to challenge hegemonic forces within the state and the markets, and within civil society itself (Anheier 2005:56). Both religion and development are deeply embedded within civil society. Whilst not subsumed within civil society, many of the ideas, values, institutions, organisations and networks of religion are formed and located within and are in dialogue with other components of civil society (Miller 2011). Civil society is a place where Christians can have a common witness with secular groups on behalf of freedom and justice and where the concerns of Christians often closely track the concerns of secular civil society (Skreslet 1997; see Magezi 2012:2-3).

Development and civil society are also entwined, with civil society providing the locale for non-state development actors. Civil society organisations are the operative agents within civil society, and the many different types of CSOs share the characteristics of being formally constituted, private, non-profit distributing, self-governing and voluntary (Lewis & Kanji 2009:10). One type of CSO is the NGO, which refers to organisations 'concerned with the promotion of social, political or economic change' (Lewis & Kanji 2009:8-11). Especially since the 1980s, the concept of civil society was 'grabbed by NGOs as one relating closely to their own natural strengths' (Whaites 2000:126) and provides a conceptual framework for thinking about NGOs and their contribution (Lewis & Kanji 2009:140). As a religious actor involved in development, the CDO is positioned as that 'small portion of all religious organisations that is "NGO-like"' (Tomalin 2012:13), often taking on the operative and visible form of an NGO.12 However, in naming and defining the CDO, it is the contention that it should not be subsumed as a sub-type of the NGO (for example, as a faith-based NGO or a Christian NGO) as it also has characteristics unique to religious organisations and the adherence and practice of a religious faith (in this case the Christian faith) which are fundamentally formative to the organisation, as will be discussed below when looking at the faith dimension.

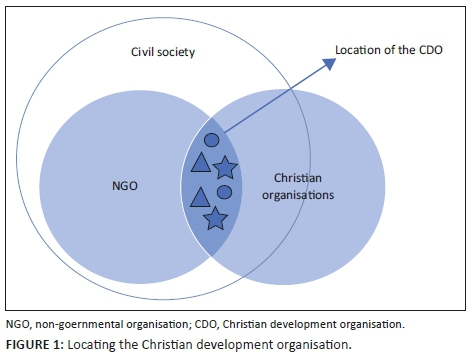

In positioning the CDO organisationally, and with reference to the aforementioned conundrum of the FBO, the CDO may be located with the help of Matthew Clarke (2011:14-20) by engaging his suggested seven possible ways of understanding the relationship between FBOs and NGOs. These are vector, distinct, substitutive, subset, co-existing, atomistic grouping and constitutive. In narrowing the focus to the CDO as a distinctly Christian organisation which is simultaneously NGO-like, one is led to exclude Clarke's distinct, substitutive, subset and constitutive models. It is, however, possible to start with his model of co-existence, as the CDO and NGO certainly co-exist within civil society. However, they do more than co-exist, and the close relationship between the CDO and the NGO must be considered whilst not subsuming the CDO within the NGO. Hence, the CDO can be seen to exist in the overlap and sit in the vector of the NGO and the broader grouping of Christian organisations. But within the overlap, the CDO is a highly diverse group of organisations, an atomistic grouping with each CDO its own, living, unique and open system. The location of the CDO is depicted in Figure 1 by combining Clarke's models of co-existence, vector and atomistic grouping.

Despite the 'muddle and delirium' (Keane 1998:36) from which talk about civil society and its organisations is not immune, the CDO's organisational and societal location and legitimacy may, without contention, be said to be as that of a CSO, with characteristics of both religious and development organisations. And its fundamental nature as an organisation, conceived as an open, living system, is definitive of its nature and functioning.

Purpose dimension

It has been suggested that NGOs are 'geared to improving the quality of life for disadvantaged people' (Vakil 1997:2060) and the same is true for CDOs. Building on people-centred approaches where 'development is about people' (Davids & Theron 2014:66), the overarching purpose of the CDO may be posited as the promotion of human well-being. In support of this view, Coetzee (2001:119) states that development is more than the satisfaction of basic needs and must include the right to live a meaningful and worthy life, and is therefore based on human well-being which seeks to achieve 'increased humanness'. Coetzee (2001:125) asserts that a key element in development as well-being is that the people who are the focus of development activities define their aspirations and needs. These are not only material needs but are 'open to the whole range of human experience: from spiritual and psychological to social and material' (Coetzee 2001:126).

Development as well-being includes the restoration of meaning as a reaction to meaninglessness and a search for a more meaningful and more human existence (Coetzee 2001:137). Tsele (2001:207) reminds us that 'development must be comprehensively constructed in relation to diverse factors that affect the totality of human existence' (see also Chambers 1997:11-12; Korten 1990:67; Sen 2001:3-11). Christian writers on development express similar understanding. De Gruchy (2005:29), for example, defines development as 'social, cultural, religious, ecological, economic and political activities that consciously seek to enhance the self-identified livelihoods of the poor'. Myers (1999:3) sees development as 'seeking positive change in the whole of human life materially, socially, and spiritually'. Well-being is personal but also communal, and the goals of transformational development are the recovery of identity and vocation as well as just and peaceful relationships (Myers 1999:14).

Activity dimension

In its activity dimension, the CDO promotes human well-being through development activities. Development is a vast, varied and contested field. Actors in development include state, market and societal ones and each engages development from their own agenda, development theory and type of activity. Development activities range from those of multi-government initiatives led by the United Nations to the volunteer activities of small community-based groups. Greater definition of the type of activities typically undertaken by CDOs is, however, required for a meaningful definition. In order to do so, it is necessary to identify the development niche of these organisations. The CDO, as has been discussed above, is 'NGO-like' and has much in common with a development NGO. By considering the NGO it is possible to make inferences about the CDO. However, when looking at the development NGO one is faced with the reality of a highly diverse group of organisations about whom it is difficult to make generalisations (Lewis & Kanji 2009:2). One way of understanding the activities of these NGOs is to consider the various roles they normally fulfil. Lewis and Kanji (2009:12-13) refer to three main sets of activities that NGOs undertake which indicate three roles.13 Firstly, there is the implementer NGO whose activities include direct provision of a wide range of goods and services to people in need of help and relief, funded either from their own organisational resources or subcontracted by governments and other donors. Secondly, the catalyst NGO that seeks to 'inspire, facilitate or contribute to improved thinking and action to promote change' (Lewis & Kanji 2009:13). In this role, NGOs may work with individuals or groups whom they consider would benefit from change, or they may direct their activities towards governments, business and donors to change their policies and approaches. Activities include, for example, community mobilising, research, lobbying and advocacy. Thirdly, there is the partner NGO who, through development cooperation, works with government, business and donors on joint activities providing specialist input to multi-organisation programmes. Partnership is also commonly between northern donor NGOs and southern implementing NGOs.

Another way of understanding the development activities of the CDO is to consider the development theories most usually reflected in the work of development NGOs. Non-governmental organisations (along with CDOs) most frequently follow human development approaches which define development as capacitation where 'human development is the means and end of development' (Nederveen Pieterse 2010:187). Following the thinking of De Gruchy (2003), CDOs are at their best when the person in difficult socio-economic circumstances is assisted to be - and has the freedom to be - the primary agent in his or her own development through dialogical action. Davids and Theron (2014:66) posit that NGOs are especially suited to micro-approaches given their ability to work with disadvantaged communities, use participatory approaches to planning and implementation, work with local institutions, be innovative, flexible and experimental, and undertake projects at low costs.14 These strengths make them distinctly different from for-profit and government organisations. Whilst often worked out as micro-development approaches working directly with people and communities in difficult socio-economic circumstances, people-centred approaches must not preclude the need for CDOs to also adopt macro-development strategies such as advocacy and public education to promote their people-centred agenda (Davids & Theron 2014:65-66; see Nederveen Pieterse 2010:186). In looking at the development activities of the CDO, a strong parallel has been drawn between those of the CDO and the development NGO. It is not a requirement of the proposed definition that a CDO should exhibit overt religiosity in its activities or include activities such as prayer, evangelism and biblical teaching in order to be considered a CDO.15 The extent to which such activities are included by a CDO depends on the understanding and application of its Christian faith, which will now be considered.

Faith dimension

The faith dimension is the dimension which shapes the Christian distinctiveness of the CDO as it seeks to be guided by its understanding and application of the Christian faith. The faith dimension and the expression of the Christian faith to which it is seeking to adhere is defined by the organisation itself - explicitly or implicitly. The CDO as an independent, voluntary organisation is often not constrained by a denominational or doctrinal stream and is free to find its own faith expression. As the CDO is an organisation, it is a collective faith expression, but one which is often strongly shaped by the leadership's understanding and application of their faith (James 2009:3-4).

The only definitional constraint being proposed is an understanding of the Christian faith as the practice of 'the religion founded on the life, teachings, and actions of Jesus Christ' (McKim 2014). Within this, the CDO may show signs of being more evangelical, ecumenical, Pentecostal, liberal, conservative or any other demarcation typically used to categorise Christians, or indeed an eclectic mix of them all. As voluntary organisations, CDOs find their own expression of the Christian narrative, fed as they usually are from multiple faith sources represented by their staff, volunteers, beneficiaries, donors and partner organisations. Their faith dimension also contains (even if by omission) their view of the church, their ecclesiology, which is implicit in their programming and may vary from very low to quite high. It should be noted that organisations not seeking to be guided by their understanding and application of the Christian faith therefore do not fit the proposed definition of the CDO, even if they are organisations with historic or current links with the church and faith structures. As Clarke (2008:15) says about the FBO: 'The faith element … is not an add-on to its development activity. It is an essential part of that activity, informing it completely'.

Given that CDOs focus on all people within their chosen beneficiary group and not only on Christians (which is predominantly the case for local church), the emphasis of the CDO's faith dimension is on lived experience over a sacramental and doctrinal framing and positioning of their faith. It is a practical faith that seeks, hopes and works for the well-being of people in difficult situations. This in turn leads to the development of operative theologies (often not written but alive in organisational culture and strategies) related to their area of work, for example homelessness, joblessness, disaster relief, children at risk or any other focus area. In addition, the CDO chooses the extent to which its Christian faith is made known in its public identity. Once again, a public Christian identity is not required by the proposed definition. There are times when strategic discernment as well as contextual operating constraints necessitate no public expression. Other CDOs may choose a very overt Christian identity.

Whilst focussed primarily on development activities for human well-being, this does not preclude the CDO from activities which would typically be thought of as religious, such as evangelism, discipleship, prayer, worship, Bible teaching and so forth. Some occasionally include sacramental aspects in their work, such as communion and baptism which are normally considered the domain of churches. The organisation's understanding and application of their Christian faith may lead it to include these activities either internally with the organisational team or externally with their beneficiaries. However, this is not a defining requirement of a CDO.

The above five dimensions constitute the proposed definitional dimensions of the CDO. Two more are worth exploring to add greater richness to the understanding of the CDO, namely the historical dimension and the relational dimension.

Historical dimension

Viewed historically, it is evident that the CDO has grown within the entwinement of missiological convictions and development sector opportunities.16 Around 1948, at the time when the concept of development and the industry for its propagation was being birthed, there already existed many Christian organisations outside the structures of the local congregation who were concerned with, amongst other things, the holistic well-being of people. Mission organisations are the most notable examples. Although primarily seeking to preach the gospel and establish churches, in the 'simple logic of the gospel' they included activities for improving the material conditions and general well-being of those to whom they went (Newbigin 1995:92).

However, the success of the missionary movement, which had resulted in the spread of Christianity and the growth of the church beyond the West, in conjunction with both the winding down of the colonial project and the critique of Enlightenment certainties, contributed to the one-directional model of mission (and the mission organisations) being replaced to a large extent by interchange and strengthening of the 'younger' churches (Newbigin 1994:177-189; Walls 1996:260). But the Christian impulse to voluntarily seek the well-being of those in difficult circumstances did not disappear with the receding of the missionary movement. Walls (1996:243) states, regarding the earlier rise of mission societies within the missionary endeavour, that 'a new concept needed a new instrument' and the same may be said regarding the CDO as a development organisation, but one formed around and seeking to hold to its Christian identity and beliefs. As with mission organisations before them, CDOs have been able to 'circumvent the usual machinery of the church' (Walls 1996:246) and find a contemporary 'means' (with reference to Williams Carey 1792).

Exploring the historical dimension of the CDO shows a highly diverse group of organisations, with identities and roots in mission organisations, diaconal institutions and charities, both large and small, Northern and Southern, with a range of Christian beliefs. They have worked either directly with the development industry or indirectly in its wake to achieve their chosen purposes, be they transformative or liberationist, primarily evangelistic or primarily social action. The CDO, it may be suggested, is the child of 'the old age of the missionary movement' (Walls 1996:255), wedded to the youthful development era. The CDO is truly a response to themes of 20th and 21st century mission and development thinking, painted on the canvas of world history.

Relational dimension

Relationships with other faith and non-faith structures are important in understanding the CDO (Occhipinti 2015:341). The CDO exists in a web of relationships which help to shape its identity. In this relational dimension three primary relationships are considered: with development NGOs, with other CDOs and with local congregations.

The CDO17 has been and continues to be strongly influenced by its alignment with secular development NGOs (Burchardt 2013:2; Tomalin 2012:9; see for example, the inclusion of secular development analysis and methods in Myers 1999). This association has positively influenced its organisational structures, access to funding, partnerships, work niche, programme design and so forth. Through this alignment in identity and work methods, the CDO has been able to access resources, programmatic approaches, capacity-building, networks and more. It has also led to greater external accountability and scrutiny of the work of the CDO, as well as professionalising their work (Myers 2010:125). Beyond these organisational impacts, there has also been the establishment of, at times, hard won common ground between FBOs and NGOs (Clarke & Jennings 2008:4). As much as the CDO has benefitted from its alignment with the development NGO, it is now likewise exposed to some of the challenges and criticisms facing these organisations. The NGO age of the 1980s and 1990s resulted in their mainstreaming and 'respectability' and led to critique that they are now too deeply enmeshed in the promotion of Northern state interests to provide any kind of alternative, especially to neo-liberalism (McEwan 2009:185-186). Tensions exist between professionalised and activist structures and identities of NGOs, and this applies equally to CDOs (Lewis & Kanji 2009:213). In addition, with greater inclusion of faith in development comes the danger of cooperating with a development sector which is still not wanting to engage and integrate religious belief per se and where an authentic approach is still needed (Rakodi 2012b:622). The CDO at this time needs to reflect on its means and how to maintain its identity and the application of the Christian faith whilst seeking cooperation with other development sector actors, especially in light of the fact that faith has always had an 'intense, but uneasy relationship with development' (James 2011:109). Positively, in terms of the necessary post-development critique of many of the assumptions of modernity and development as economic progress, CDOs have the potential to move beyond critique to 'contribution, exhibiting the nonchalance of faith … delivered from the false creed of redemption through history, and thereby more able to contribute to justice' (De Gruchy, Holness & Wüstenberg 2002:133-148). Perhaps a key contribution of the CDO to development at this time will be to 'retrieve hope from the collapse of progress' (Nederveen Pieterse 2010:196).

Moving now to relationships between CDOs, it is important to bear in mind (as discussed above) that they are a highly atomistic group of organisations, reflecting the diversity found in both development NGOs and Christian faith expressions. Sharing a common faith may provide unity of purpose, natural partnering, funding free from restraints for faith-centred work and a common narrative of development which helps to support the CDO's Christian identity. At the same time, a shared faith does not guarantee easy and effective partnering. Despite the 'convergence of convictions', the historic split between evangelical and ecumenical organisations regarding the relationship of evangelism and social action continues to create plurality in CDOs (Bowers Du Toit 2010:264-266). In addition, Myers (2015) highlights differences between the grassroots progressive Pentecostal and charismatic organisations (often found in the global South) and the mainline (usually Northern) Christian development agencies in terms of their analysis and solutions, where the former tend to emphasise personal sin and the need for transformation, the latter focusing more on structural causes. Whilst this can lead to an inability to work together, it gives CDOs collectively the opportunity to address holistically the issues that inhibit human well-being through combining their different approaches.

A final relationship to be considered is the CDO's relationship with the local congregation. Christian development organisations have a close but at times contentious relationship with congregations (Bowers Du Toit 2017:4). They are different in significant ways and have differing priorities. Most of the activities of a congregation are focussed around the provision of spiritual services to its members, including dispensing sacraments, teaching and pastoral care with perhaps some social outreach and evangelism within its wider context, whilst the CDO provides relief and development services within their chosen community or group irrespective of the faith conviction of the people seeking their help. This supports Flett's (2010:196) contention of a breached Christian community that prioritises 'contemplative being and a derivative missionary act' and the cultivation of the faith over its communication (Flett 2016).

This is also reflected in the institutional versus movement nature of the church and the CDO respectively (Samuel 2010:134). Against the backdrop of these fundamental differences, CDOs - for pragmatic, sociological and missiological reasons - are however increasingly seeking to work with and through congregations, but 'all is not well' (Sugden 2010:35; see Jochemsen 2018:99-101). Work must be done by both the CDO and the congregation to understand better where the congregation fits within development on the ground (Myers 2010:122; see also Magezi 2012). The relationship between the CDO and the congregation needs sociological, theological and, particularly, missiological reflection and direction at this time.

Conclusion

This article sought to name and define organisations doing development from a Christian faith motivation. In reviewing the literature, many contending and conflicting names and definitions were found, but none in common use that are suitable for enabling greater engagement and understanding of these organisations within the fields of theology and development. Christian development organisation was proposed as a suitable name and defined as 'a civil society organisation that exists to promote human well-being through development activities, guided by its understanding and application of the Christian faith'. Five definitional dimensions were identified, namely organisational, societal, purpose, activity and faith. Additionally, the history dimension added a rich understanding of the origins and formation of the CDO whilst the relationship dimension positioned the CDO within a web of relational dynamics. The definition is empirical, rather than normative, and is intentionally broad, seeking to avoid the schisms so common to both religion and development. Having in many ways grown out of the mission organisation of previous centuries, the CDO continues to exist within 'the dance between religious belief and development' (Clarke 2011:1). It has adopted the structures and approaches provided by development to seek human well-being from a Christian perspective whilst continuing to be influenced by theological and more especially missiological developments over the past 100 years. It is hoped that the name and definition offered in this article will promote research and engagement with the CDO as well as aid in the self-understanding of these organisations.

Acknowledgements

This article forms part of a National Research Foundation (NRF) Competitive Unrated Grant (CSUR150623120252-9918) project entitled: '"Does faith matter?" Exploring the role of faith based organisations as civil society actors'.

Competing interests

The author declares she has no financial or personal relationships which may have inappropriately influenced her in writing this article.

Author's contributions

D.M.H. is the sole contributor to this research article.

Ethical considerations

The project received ethical clearance from Stellenbosch University (clearance number: SU-HSD-003625).

Funding information

Financial support received from the NRF as part of an NRF Competitive Unrated Grant (CSUR150623120252 - 9918).

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in the article are that of author and not an official position of the institution or funding agency.

References

Adkins, J., Occhipinti, L.A. & Hefferan, T., 2010, Not by faith alone: Social services, social justice, and faith-based organizations in the United States, Lexington Books, Lanham. [ Links ]

Anheier, H.K., 2005, Nonprofit organizations: Theory, management, policy, Routledge, London. [ Links ]

Bartelink, B.E., 2016, 'Cultural encounters of the sexular kind', PhD thesis, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen. [ Links ]

Berger, J., 2003, 'Religious nongovernmental organizations: An exploratory analysis', Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 14(1), 15-39. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022988804887 [ Links ]

Beyers, J., 2011, 'Religion, civil society and conflict: What is it that religion does for and to society?', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 67(3), Art. #949. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v67i3.949 [ Links ]

Bowers Du Toit, N., 2010, 'Moving from development to social transformation - Development in the context of Christian Mission', in I. Swart, H. Rocher, S. Green & J. Erasmus (eds.), Religion and social development in post apartheid South Africa, pp. 261-273, SUN Press, Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Bowers Du Toit, N.F., 2017, 'Meeting the challenge of poverty and inequality? "Hindrances and helps" with regard to congregational mobilisation in South Africa', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 73(2), a3836. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v73i2.3836 [ Links ]

Burchardt, M., 2013, 'Faith-based humanitarianism: Organizational change and everyday meanings in South Africa', Sociology of Religion 74(1), 30-55. https://doi.org/10.1093/socrel/srs068 [ Links ]

Carey, W., 1792, An enquiry into the obligations of Christians to use means for the conversion of the heathens, Anne Ireland, Leicester. [ Links ]

Chambers, R., 1997, Whose reality counts?, Practical Action Publishing, Warwickshire. [ Links ]

Clarke, G., 2006, 'Faith matters: Faith-based organisations, civil society and international development', Journal of International Development 18(6), 835-848. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1317 [ Links ]

Clarke, G., 2008, 'Faith-based Organisations and International Development', in G. Clarke & M. Jennings (eds.), Development, Civil Society and Faith-Based Organisations- Bridging the Sacred and the Secular, Palgrave Macmillan, London. [ Links ]

Clarke, M., 2011, Development and religion: Theology and practice, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham. [ Links ]

Clarke, M., 2015, 'Friend or Foe? Finding Common Ground between Development and Pentecostalism', PentecoStudies: An Interdisciplinary Journal for Research on the Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements 14(2), 156-175. [ Links ]

Clarke, G. & Jennings, M., 2008, Development, civil society and faith-based organizations: Bridging the sacred and the secular, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke. [ Links ]

Cochrane, J.R., 2016, 'Religion in sustainable development', The Review of Faith & International Affairs 14(3), 89-94. https://doi.org/10.1080/15570274.2016.1215818 [ Links ]

Coetzee, J.K., 2001, Development: Theory, policy and practice, Oxford University Press, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Daft, R.L., 2004, Organization theory and design, Thomson/South-Western, Mason, OH. [ Links ]

Davids, I. & Theron, F., 2014, Development, the state and civil society in South Africa, Van Schaik, Pretoria. [ Links ]

De Gruchy, S., 2003, 'Of agency, assets and appreciation: Seeking some commonalities between theology and development', Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 16(117), 20-39. [ Links ]

De Gruchy, S., 2005, 'Integrating mission and development: Ten theological theses', International Congregational Journal 5(1), 27-36. [ Links ]

De Gruchy, J.W., Holness, L. & Wüstenberg, R.K., 2002, Theology in dialogue: The impact of the arts, humanities, and science on contemporary religious thought: Essays in honor of John W. de Gruchy, William B. Eerdmans, Claremont. [ Links ]

Deneulin, S. & Rakodi, C., 2011, 'Revisiting religion: Development studies thirty years on', World Development 39(1), 45-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2010.05.007 [ Links ]

Flett, J.G., 2010, The witness of God: The trinity, missio Dei, Karl Barth, and the nature of Christian community, W.B. Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Flett, J.G., 2016, Apostolicity: The ecumenical question in world Christian perspective, InterVarsity Press, Downers Grove, IL. [ Links ]

Freeman, D., 2018, 'From "Christians doing development" to "doing Christian development": The changing role of religion in the international work of Tearfund', Development in Practice 28(2), 280-291. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2018.1418837 [ Links ]

Haddad, B., 2015, Keeping body and soul together: Reflections by Steve de Gruchy on theology and development, Cluster Publications, Pietermaritzburg. [ Links ]

Haddad, B., 2016, 'Curriculum design in theology and development: Human agency and the prophetic role of the church', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 72(4), a3432. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v72i4.3432 [ Links ]

James, R., 2004, Space for Grace, Swedish Mission Council, Sundbyberg. [ Links ]

James, R., 2009, What is distinctive about FBOs? How European FBOs define and operationalise their faith, INTRAC Praxis Paper 22, INTRAC, Oxford. [ Links ]

James, R., 2011, 'Handle with care: Engaging with faith-based organisations in development', Development in Practice 21(1), 109-117. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2011.530231 [ Links ]

Jeavons, T.H., 1997, 'Identifying characteristics of "religious" organizations: An exploratory proposal', in J. Demerath, III, P.D. Hall, T. Schmitt & R.H. Williams (eds.), Sacred companies:Organizational aspects of religion and religious aspects of organizations, pp. 79-95, Oxford University Press, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Jeavons, T.H., 2003, 'The vitality and independence of religious organizations', Society 40(2), 27-36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-003-1049-1 [ Links ]

Jochemsen, H., 2018, 'For the twig to blossom…' : Cooperation in development from a Christian perspective, Shaker Publishing, Maastricht. [ Links ]

Jones, B. & Juul Petersen, M., 2011, 'Instrumental, narrow, normative? Reviewing recent work on religion and development', Third World Quarterly 32(7), 1291-1306. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2011.596747 [ Links ]

Keane, J., 1998, Civil society: Old images, new visions, Stanford University Press, Standford, CA. [ Links ]

Korten, D.C., 1990, Getting to the 21st century: Voluntary action and the global agenda, Kumarian Press, West Hartford, CT. [ Links ]

Lewis, D. & Kanji, N., 2009, Non-governmental organizations and development, Routledge, London. [ Links ]

Magezi, V., 2012, 'From periphery to the centre: Towards repositioning churches for a meaningful contribution to public health care', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 68(2), Art. #1312, 8 pages. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v68i2.1312 [ Links ]

Manji, F. & O'Coill, C., 2002, 'The missionary position: NGOs and development in Africa', International Affairs 78(3), 567-584. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.00267 [ Links ]

McEwan, C., 2009, Postcolonialism and development, Routledge, London. [ Links ]

McKim, D.K., 2014, The Westminster dictionary of theological terms, Westminster Press, Louisville, KY. [ Links ]

Miller, D.E., 2011, 'Civil society and religion', in M. Edwards (ed.), The Oxford handbook of civil society, pp. 257-269, Oxford University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Myers, B.L., 1999, Walking with the poor, Orbis Books, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Myers, B.L., 2010, 'Holistic mission: New frontiers', in B.E. Woolnough & W. Ma (eds.), Holistic mission: God's plan for God's people, pp. 119-127, Regnum, Oxford. [ Links ]

Myers, B.L., 2015, 'Progressive pentecostalism, development, and Christian development NGOs: A challenge and an opportunity', International Bulletin of Mission Research 39(3), 115-120. [ Links ]

Myers, B., Whaites, A. & Wilkinson, B., 2000, 'Faith in development', Georgetown Journal of International Affairs 1(1), 35-39. https://doi.org/10.1177/239693931503900301 [ Links ]

Nadler, D.A. & Tushman, M.L., 1980, 'A model for diagnosing organizational behavior', Organizational Dynamics 9(2), 35-51. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(80)90039-X [ Links ]

Nederveen Pieterse, J., 2010, Development theory: Deconstructions/reconstructions, 2nd edn., Sage, London. [ Links ]

Newbigin, L., 1994, A word in season: Perspectives on Christian world missions, W.B. Eerdmans, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Newbigin, L., 1995, The open secret: An introduction to the theology of mission, Rev. edn., W.B. Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Occhipinti, L.A., 2015, 'Faith-based organizations and development', in E. Tomalin (ed.), The Routledge handbook of religions and global development, pp. 331-345, Routledge, London. [ Links ]

Oxford English Dictionary, 2019, Definition of organisation in English by Oxford Dictionaries, OED, Oxford. [ Links ]

Rakodi, C., 2012a, 'A framework for analysing the links between religion and development', Development in Practice 22(5-6), 634-650. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2012.685873 [ Links ]

Rakodi, C., 2012b, 'Religion and development: Subjecting religious perceptions and organisations to scrutiny', Development in Practice 22(5-6), 621-633. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2012.686602 [ Links ]

Samuel, V., 2010, 'Mission as transformation and the Church', in B.E. Woolnough & W. Ma (eds.), Holistic mission: God's plan for God's people, pp. 128-136, Regnum, Oxford. [ Links ]

Sen, A., 2001, Development as freedom, Oxford University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Sider, R.J. & Unruh, H.R., 2004, 'Typology of religious characteristics of social service and educational organizations and programs', Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 33(1), 109-134. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764003257494 [ Links ]

Skreslet, S.H., 1997, 'Networking, civil society, and the NGO: A new model for ecumenical mission', Missiology: An International Review 25(3), 307-319. https://doi.org/10.1177/009182969702500304 [ Links ]

Sugden, C., 2010, 'Mission as transformation - It's journey among evangelicals since Lausanne I', in B.E. Woolnough & W. Ma (eds.), Holistic mission: God's plan for God's people, pp. 31-36, Regnum, Oxford. [ Links ]

Swart, I., 2008, 'Meeting the challenge of poverty and exclusion: The emerging field of development research in South African practical theology', International Journal of Practical Theology 12(1), 104-149. https://doi.org/10.1515/IJPT.2008.6 [ Links ]

Swart, I., 2010, 'Meeting the rising expectations? Local churches as agents of social welfare and development in post-apartheid South Africa', in I. Swart, H. Rocher, S. Green & J. Erasmus (eds.), Religion and social development in post apartheid South Africa, pp. 447-163, SUN Press, Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

TerHaar, G. & Ellis, S., 2006, 'The role of religion in development: Towards a new relationship between the European Union and Africa', European Journal of Development Research 18(3), 351-367. https://doi.org/10.1080/09578810600893403 [ Links ]

Thaut, L.C., 2009, 'The role of faith in Christian faith-based humanitarian agencies: Constructing the taxonomy', Voluntas 20(4), 319-350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-009-9098-8 [ Links ]

Tomalin, E., 2012, 'Thinking about faith-based organisations in development: Where have we got to and what next?', Development in Practice 22(5-6), 689-703. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2012.686600 [ Links ]

Tsele, M., 2001, 'The role of Christian faith in development', in D.G.R. Belshaw, R. Calderisi & C. Sugden (eds.), Faith in development: Partnership between the World Bank and the churches of Africa, pp. 203-218, World Bank, Washington, DC. [ Links ]

Vakil, A.C., 1997, 'Confronting the classification problem: Toward a taxonomy of NGOs', World Development 25(12), 2057-2070. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(97)00098-3 [ Links ]

Van Der Merwe, W. & Swart, I., 2010, 'Towards conceptualising faith-based organisations in the context of social welfare and development in South Africa', in I. Swart, H. Rocher, S. Green & J. Erasmus (eds.), Religion and social development in post apartheid South Africa: Perspectives for critical engagement, pp. 75-89, SUN Press, Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Walls, A.F., 1996, The missionary movement in Christian history: Studies in the transmission of faith, Orbis Books, Edinburgh. [ Links ]

Whaites, A., 2000, 'Let's get civil society straight', in J. Pearce & D. Eade (eds.), Development, NGO's, and civil society: Selected essays from development in practice, pp. 124-141, Oxfam, Oxford. [ Links ]

World Council of Churches, 2014, Ecumenical conversations - Reports, affirmations and challenges from the 10th Assembly, WCC, Geneva. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Deborah Hancox

deborah.hancox@outlook.com

Received: 24 Apr. 2019

Accepted: 13 Sept. 2019

Published: 26 Nov. 2019

Project Research Number: CSUR150623120252-9918

Note: Faith-Based Organisations, sub-edited by Nadine Bouwers du Toit (Stellenbosch University), Vhumani Magezi (North-West University) and Elisabet le Roux (Stellenbosch University).

1 . What does appear is mostly written by and for practitioners, for example, 'Space for Grace' (James 2004).

2 . It should also be noted that the definition was developed from literature as well as drawing on the researcher's 18 years' experience working as an organisational development consultant in the Christian development sector.

3 . Examples within the Christian tradition include, for example, the congregation, denominational structures, mission organisations, diaconal agencies and relief and development organisations.

4 . They also use multiple terms interchangeably, even within the same article. Sometimes there is a sense which explains variance, but often it seems like simple inconsistency.

5 . This includes topics such as policy and funding, ethics and the church response to poverty and injustice. Hence, for example, the need to identify types of faith-based organisations within policy and funding debates (see, for example, Van Der Merwe & Swart 2010:75).

6 . There is also a need, although this is not prominent in literature, to be able to discretely identify diaconal service providers and mission organisations. However, this does not seem to be as problematic, most probably because of the clearly defined roles that churches had historically with diaconal and mission organisations.

7 . The term 'FBO' has some validity within the religion and development discourse as its concern is seeking to understand, measure and evaluate religion and religious organisations within the context of development outcomes. But even this discourse reaches a point at which the particular religious faith identity needs to be deconstructed and analysed (see, for example, Bartelink 2016; Clarke 2015).

8 . It may be the case that research is being done specifically about organisations identifying as 'evangelical' but this specification would be better accommodated as a selection criterion within a more broadly inclusive category of Christian organisations active in development.

9 . A very similar name can equally be used for organisations motivated by other faiths, for example a Muslim development organisation (MDO) or a Hindu development organisation (HDO).

10 . For example, as conceived in Nadler and Tushman's (1980) congruence model.

11 . 'Household' could be used in preference to 'family' as it is more inclusive and more reflective of the functional unit found in many societies.

12 . However, in likening the CDO to an NGO, one is again (as with the FBO) faced with the challenge of understanding an extremely diverse category of organisations that is complex, unclear and 'difficult to pin down analytically' (Lewis & Kanji 2009:2).

13 . These are similar to Korten (1990:113-128).

14 . Davids and others also point out that NGOs have inherent weaknesses which need to be considered, for example initiatives not reaching the intended participants, lack of innovation and flexibility, limited organisational sustainability, programmatic and sectoral, rather than holistic, strategies and unwillingness or inability to engage government on policy issues (Davids & Theron 2014:66). To these critiques Lewis and Kanji (2009:17-18) add the following: undermining of state-led development initiatives, conversely participating in neo-liberal privatization by fulfilling contracted out public services; poor accountability; following their own agendas; self-interest; becoming professionalised and depoliticised and sapping people's movements of their focus and energy; extending neo-colonial situation between the West and the rest of the world; poor ability to demonstrate effectiveness. They run the risk of being 'ineffectual do-gooders, over professionalized large humanitarian business corporations, or self-serving interest groups' (Lewis and Kanji 2009:21). Once again, the CDO is not immune to these weaknesses.

15 . This is contra typologies such as Sider and Unruh (2004) who link the level of religiosity to the classification of the FBO.

16 . Whilst the term 'CDO' is only now being proposed, looking at its history does not represent anachronism, as it is possible to apply the definition to organisations in the past that match the proposed definition.

17 . This section draws on general FBO literature and literature about Christian development.