Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

HTS Theological Studies

versión On-line ISSN 2072-8050

versión impresa ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.75 no.4 Pretoria 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v75i4.5553

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Tweeting God: Notes on articulating a Twitter theology

Jan A. van den Berg

Department of Practical and Missional Theology, Faculty of Theology and Religion, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

ABSTRACT

As part of the search for relevant and contextual articulations of theology, this article provides an overview of a comprehensive research project that explored, described and analysed Christian motifs on Twitter. Based on the brief overview of the project, perspectives for the formulation of a Twitter theology are presented from a practical theological orientation. Two central markers are indicated and described as primary drivers of a Twitter theology: the first marker places its focus on the relationship, dynamics and functioning of aspects of authority and normativity in facilitating a Twitter theology. The second marker puts particular emphasis on the value and significance of using aphoristic formulations in the elucidation of a comprehensible Twitter theology. The article presents important strategic perspectives on the practice of a Twitter theology, as well as the formulation of a relevant contextual theology.

Keywords: practical theology; Twitter; normativity; authority; aphorism; lived religion.

Appraisal

To my mind, theology is much more a verb than a noun. This evolving understanding already appeals to me as a student who listens to the lectures of Prof. Maake Masango. Prof. Masango's research, his ministry and his personal relationships all testify to the embodiment of theology as a verb. Even Maake's humour reminds me of the deepest theological truths that can be found in the strangest moments of everyday life. As an expression of my appreciation for all that he has contributed to my life, I gladly present Prof. Maake Masango with the perspectives reflected in this article.

Introduction

This Twitter message by Pope Francis (Figure 1) opens a window to the multiple vistas of meaning associated with a research project1 on the finding and meaning of Christian motifs on Twitter. In sending out this message on 15 March 2015, the Catholic News Service (@CatholicNewsSvc 2015:n.p.) has seamlessly embedded the age-long religious tradition of the Catholic Church within the current digital age and culture. I provide some of the eye-catching aspects of this message. Pope Francis' name is coupled with probably one of the most well-known and iconic symbols of popular culture, namely the hashtag ('#').2 The composer of the tweet was well aware that the application of this technique would escalate the impact of the message on the social media world.

Typical of Twitter culture, the minimum words are used with maximum meaning. In this instance, a mere 16 words summarise gospel message, which is usually associated with voluminous books.

The purpose of the research project was to offer an extensive practical theological analysis, in order to map the possible occurrence, meaning and communication of Christian motifs as understood, in the broadest possible sense, on Twitter. My motivation behind the research project was my own observation that theological language3 has lost its impact in many respects and that many people have turned a deaf ear to the articulation of these truths. Questions could therefore be raised regarding possible alternatives and existing practices for the translation of theological concepts into a more understandable and relevant language. This also articulates well with my own conviction of the importance of informal or everyday expressions of theology. That is, theological language does not exclusively belong to the domain of formal academy, but everyday life provides a rich canvas for incorporating various forms of 'ordinary theology', 'espoused theology', 'implicit religion', 'operant theology', 'everyday theology' and 'lived religion'.4

Sensitive to the new possibilities offered by social media, I sought new meanings of relevance and innovation within specific contexts. In seeking a focused practice(s) from which the empirical research would be administered, I have concentrated on the meaning of the social media platform Twitter. By means of exploratory empirical strategies and backed by a literature study, I was exploring a new field in practical theology, which as praxis gave expression to my own search for relevance, actuality and contextuality. In this search, I examined new empirical research methods and vistas in an interdisciplinary manner.5

With the aim of summarising perspectives on the basis of the research and in answer to the various research questions, this article provides a critical-reflective synthesis of the findings of the project. The critical-evaluative summary of the research is therefore directed by the central concept of theological reflection in a practical theology orientation (Ballard 2012:169; Lyall 2000:53; Reader 2008:14-17; Swinton & Mowat 2006:59).

Two main rubrics form the basis of this article. The rubric 'Mapping' summarises the preceding research, while based upon completion of this charting, the second main rubric, 'Directions', presents specific concrete and strategic perspectives emerging from the completed research.

Mapping

A mapping of stories

Although the concept of reflexivity is directly related to theological reflection, it also strongly encapsulates an autobiographical notion of discernment trying to comprehend the self in a networked society (Moschella 2012:225; Reader 2008:14). Acknowledging that autobiographical perspectives form part of the process of critical reflection, Graham (2017) has therefore rightly pointed out that:

It is not about reducing practical theology to autobiography but seeing how our standpoints and concerns have informed our intellectual and academic interests, and vice versa. In the interests of integrity and transparency, the self as researcher as one who brings particular presuppositions, questions and interests, must be prepared to write themselves into the text of their research. (p. 70)

This notion of 'writes themselves into the text' has, interesting enough also, manifested itself in the democratisation brought about by social media. Newby (2008) describes the meaning thereof for the character and dynamics of religious texts as follows:

The electronic revolution seems to be having the same impact on sacred texts as the Gutenberg technology did: more texts available to more people with a greater loss of control over the texts by the established authorities … the electronic revolution in the use of sacred texts will negotiate between the two poles of stasis and resistance on the one hand and proliferation and chaos on the other. (p. 57)

The composition of a message on Twitter can serve as an example to illustrate this bipolar tension between stasis, on the one hand, and change, on the other hand. The Twitter's icon that is used as a button to guide the formulation of a tweet is the classic quill, used primarily as a writing tool from the 6th to the 19th centuries.

Composing a newly formulated message on Twitter is thus associated with the meaning of a classical writing implement that is no longer used. This image succeeds in indicating the tension between stasis and change. According to Newby, the use of holy texts in the digital revolution will be negotiated between two poles, namely 'stasis/resistance' and 'proliferation and chaos'.

I shall therefore use two broad coordinates, namely the bipolar tension between stasis and change, on the one hand, and the issue of the functioning and connection between theological and practical knowledge, on the other hand, to present the following synthesis of, and the critical-evaluative reflection on, the research project. This will indicate perspectives for the strategic formulation and communication of 'God talk' on Twitter by presenting central themes and perspectives derived from the research.

In general, the nature of Twitter messages points to a strong autobiographical element that contributes to the integrity and authentic nature of the content. In terms of the content, there are strong links between the commemoration of prominent Christian festive days and the Christian interpretation of actual events that occur against the background of a contemporary culture. Although well-known and conventional words and concepts within the Christian tradition are used, the various Twitter messages often include elements of creative and innovative humour, critical comment and motivating accents.

Unlike my initial expectation, the various Twitter data sets did not provide new formulations of faith or theology. On the contrary, the use of traditional words associated with the Christian faith dominated the various data sets. In this regard, the data and the analysis thereof show a specific 'stasis' or even 'resistance', in that the words associated with the classical Christian faith and theology still prevail in the various data sets. In the majority of instances, the message remains the same; the only difference is the way in which the message is conveyed. In this respect, the opposite pole of 'proliferation' and 'chaos' is obvious.

The use of the hashtag sign, which makes different words distinguishable, creates new meaning that usually shows a unique connection with a specific real event, creating a special contextual accent. It is interesting to note how the traditional meaning of words and concepts, especially those associated with expressions of and events in popular culture, acquires new characteristics within this new contextual setting.

In summary, the following important themes can be gleaned from the research:

-

The articulation and facilitation of faith, especially in association with Christian motifs, obtains a new dynamic with the use of Twitter.

-

Twitter offers a platform on which individuals and communities can personally and socially express various aspects of being human in terms of Christian motifs.

Directions

The strategic or pragmatic dimension inherently forms part of the nature of practical theology. In terms of the strategic-pragmatic perspective, it appears that traditional Christian motifs still persist and correspond uniquely to daily life. New meanings do emerge from this link of Christian motifs to real events, and often to expressions of popular culture. This is emphasised by the fact that the holy and the profane often coexist and function within the space of 140 characters.6 This fact begs a critical, evaluative theological reflection on numerous levels. In the apparent paradoxical moments of life, '[t]he ambiguities, inconsistencies, and open-endedness of Christian practice are, however, the very things that establish an essential place for theological reflection in everyday Christian lives' (Tanner 2002:232).

A practical theology of tweeting God

It is evident from the research that Christian motifs are portrayed in a dynamic way on the Twitter platform.

The nuances in the variously used Christian motifs cover a wide spectrum of a public practical theology that describes several aspects of being human. In support of this perception is the belief that lived popular culture impacts on the moulding of an individual's life (Sweet 2012:n.p.). This leads to the understanding of the hermeneutics of popular culture as '… the shared environment, practices, and resources of everyday life for ordinary people within a particular society' (Lynch 2005:14). Although the classical and traditional language of faith still forms part of Twitter formulations, it is used in such a way that it conveys fresh and new meaning. This implies new possibilities for church, theology and faith.

The articulation and facilitation of faith, especially in association with Christian motifs, obtains a new dynamic with the use of Twitter. The research shows how messages on Twitter make a unique contribution to the description of Christian themes. Interestingly, new meaning possibilities are revealed in tracing the meaning of the use of humour on Twitter and the way in which Christian motifs are accentuated in this regard. The research also found that Twitter, in particular, provides not only a space for confirming traditional truths of faith but also a space for expressing perspectives associated with lived religion, in which Christian motifs can be traced and distinguished. Various emotions such as humour and aggression associated with human traits are associated with the expressions of specific Christian motifs. Indeed, the creative and relevant expression of Christian themes associated with human emotions further emphasises the real and relevant role and significance of Twitter.

Throughout the research, a number of prominent aspects emerged. Firstly, there are, indeed, resemblances, but also big differences between a so-called online and offline identity or presence. Secondly, it is observed that there are indeed possibilities of writing meaningful about theological ideas with the limited characters available. The use of concise observations can potentially influence many more people because of the extent of Twitter's reach as well as the dynamics associated with the social media platform. This preliminary description contributes to the understanding that 'practice itself enacts and names theology' (Campbell-Reed & Scharen 2013:241), leading to the formulation of an ordinary theology articulating a 'faith and a spirituality, and incorporates beliefs and ways of believing' (Astley 2013:n.p.). In mapping the expression of Christian motifs on Twitter, cognisance is given to the understanding that (Graham 2013):

[F]aith is something to be practised and not just believed; and [that] one of the tasks of practical theological research is to investigate and interpret the lived experience of people of faith. (p. 159)

The popular theologian Leonard Sweet has encapsulated some of the aspects of this challenge in his article, 'Twitter theology: 5 Ways Twitter has changed my life and helped me be a better disciple of Jesus', indicating that 'Twitter makes me a better Jesus disciple, partly because Twitter is my laboratory for future ministry' (Sweet 2014).

Therefore, in a unique way, the use of Twitter serves to illustrate Marshall McCluhan's observation that '… media aren't just channels of information. They supply the stuff of thought, but they also shape the process of thought' (Carr 2010:6). Arising from and in congruence with the strategic character of practical theology (Osmer 2008:175-176), perspectives and context-specific examples regarding a pragmatic and dynamic interaction with Twitter can be provided with the aim of developing a practical theology of tweeting God.7

These perspectives could lead to newly informed practices and fresh expressions of being church in the world.

Sprouting from the documented research, I have identified the particularly significant themes of (1) normativity and authority and (2) aphoristic theology, which warrant further reflection in a further development of a practical theology of tweeting.

Normativity and authority

Normativity is a multi-coloured concept, which is found across a wide range of disciplines and in various contexts.8

Central to the construction of normativity within the Christian tradition is the acknowledgement of sources of authority. Traditionally, sources such as Scripture and religious tradition would stand central to the constitution of normativity. What is clear from the research is that social media has established new fluid forms of normativity and authority.

As opposed to the traditional sources of authority, which are often interpreted in an apparently objective and linear manner, it would seem that:

[T]he key challenge the Internet poses to traditional structures of religious authority is the democratisation of knowledge online. The Internet not only increases access to alternative sources of religious information, but empowers people to contribute information, opinions, and experiences to public debates and conversations. (Campbell & Teusner 2011:67)

This observation suggests that the basis for the interpretation of the sources of authority responsible for normativity is shifting by means of the use of social media. The result of this is that a significant number of believers apparently take more heed of the interpretation of the traditional sources of authority by well-known, popular Christian writers and speakers, rather than of the sources themselves. The foundation of this is the comment of Byers (2013:106) that 'words can be used for asserting authority ('Gutenbergers') or for relating to others ("Googlers")' (Byers 2013:106). To confirm this observation, it is an interesting research that has shown well-known Christian speakers and writers such as Osteen and Meyer might possibly have fewer followers on Twitter than someone like Justin Bieber, but that the interaction they create with their tweets is indeed more than that of the pop sensation (Horner 2014:59).

In facilitating this conversation on normativity as portrayed in the Twitter sphere, the following markers for orientation are noteworthy: The recognition of authority on Twitter is very important in negotiating a position of normativity. This acquired authority coming from an offline world is endorsed through the number of followers as well as through messages being 'retweeted' and 'liked'. In particular, the 'retweet' function serves as an important component in establishing and building authority on Twitter (boyd,9 Golder & Lotan 2010:n.p.).

As a social media platform, Twitter offers important possibilities for articulating and facilitating normativity on various levels.10 This not only extends the understanding and meaning of normativity but also creates unique meaning, interpretation and association that bear real and relevant meaning. The meaning of normativity is thus dynamic and is negotiated anew within every context. Underlying this acknowledgement and challenge is the conviction that practical theology encapsulates a hermeneutics of the lived religion, in which preference is given to the praxis itself and to the knowledge concerning God that is being developed, found and lived within this praxis (Ganzevoort 2004:n.p.). On social media platforms, authority is construed in ways that differ from the traditional. With regard to this construction of authority in a digital era, Turner (2012:132) points out that the following factors are responsible for the dynamic negotiation and legitimisation of authority. Firstly, mass communication, supported by the use of social media, has led to a democratisation of knowledge that challenges traditional forms of authority. Secondly, free access to Christian sources and tradition (also in the case of other religious traditions) that are digitally facilitated increases the number of interpretations and interpreters of texts and the new expressions thereof. On the basis of this, it can be confirmed that '[c]laims to authority tend, therefore, to be inflationary' (Turner 2012:132). In further support of this dynamic construction and facilitation of authority, the following strategic considerations can be mentioned. The authority of the profile of the author of a specific message is determined largely by the number of followers. Consequently, a popstar acquires specific authority by the number of followers and that her message, which contains specific Christian motifs, can have much more influence than that of a respected theologian writing on the same topic. Therefore, in communicating Christian motifs on Twitter, authority is not primarily determined on the basis of the legitimisation of the content of the message according to a specific theological tradition, but rather on the basis of other contributing factors, for example, the number of followers of a specific Twitter account.11

Aphoristic theology

An aphorism is a short statement that conveys a specific truth, giving colour and meaning to life in a specific way (Grant 2016:5). The word 'aphorism', derived from the Greek apo [apart] and horos [border, and from which the word horizon is derived], was initially coined by Hippocrates; it has a rich religious and literary history (Grant 2016:8; Snowden 2012:81). There are various forms of aphorisms, and Twitter messages are an excellent example of the so-called aphoristic literature. Grant (2016) rightly states:

Twitter is exemplary of this … Twitter is, of course, an ideal forum for the advertising slogan and the news update, but it is also an environment in which a huge range of other short forms, old and new, have flourished: from running commentaries to Twitter plays, poems, and stories, citations to travel narratives, pithy synopses to witty ripostes, it pushes the boundaries of what is possible in aphoristic writing … Twitter alone swamps the aphoristic tradition. (p. 132)

A defining characteristic of aphoristic literature is the brevity of the message. This implies speed, intensity and condensation and is inevitably emphasised in Twitter messages in a specific way. Snowden (2012:92) summarises the advantage thereof as follows: 'Brevity of language has the advantage of being able to travel well and quickly, as there is less detail to lose'. In aphoristic speech, aspects of singularity and plurality are often linked to each other to create new meaning in a paradoxical way (Snowden 2012):

When we read clever, pithy language in the form of an SMS, Tweet or email it is the result of technology enabling the use of language for commentary and communication in a way Correthat is appealing and accessible within specific technically defined boundaries. (p. 92)

Throughout the contribution, I have pointed out the distinctive characteristic of Twitter messages, namely the limited number of characters. For purposes of the research, I focused only on Twitter messages that consist of words. I did not consider other possible content such as the use of photographs. This restriction on the use of characters inevitably influences the formulation and scope of the content of Twitter messages.

This specific form of tweets has emphasised the use of aphorisms in the research.

Aphoristic theology implies that the author of the Twitter message has the ability to render specific Scriptural and/or theological truths in a concise and impressive manner. For a theoretical description of the character and occurrence of aphoristic theology, the following possibilities can be mentioned. Verses can be quoted verbatim within the text limit of Twitter. Texts or parts of biblical texts can also be presented graphically to be used in a so-called remix format. The text section or theological truth can also be mixed to form a new independent expression. The theological aphorism further emphasises the author's authority, in that some letters and/or words are emphasised by means of stylistic usage (e.g. the use of a capital letter or italics). Inevitably, messages can, without the direct use of biblical texts, also refer to a theological or spiritual truth. In summary, I refer to Cheong's (2014:12) research findings regarding the possible value in the use of aphorisms: Tweets have been crafted in staccato style to quote, extract, remix and recontextualise Scripture, with implications for the role of pastoral authority in strategically shaping the (re)presentation and interpretation of Scripture via microblogging on social media.

The use and effect of the message is usually associated with the specific identity and authority of the author of the message. In identifying both the occurrence and the meaning of the aphoristic traits of tweets, the question must be raised as to the advantages and disadvantages of aphorisms in communicating Christian motifs on Twitter. The obvious restriction of the number of characters available in Twitter is far more significant than the brief aphoristic speech itself. Without commenting on the content of a specific tweet, the brief, pithy, but striking way of formulating contributes to a rapid and effective spreading of the message. In this digital era, the content of the aphoristic expression is further strengthened by underlying mechanisms such as the 'retweet', 'like' and 'hashtag' functions.

If one acknowledges a life defined by the meaning of a digital landscape, one accepts the strategic value and significance of the aphorism in communicating Christian motifs. This research reveals that conventional words associated with the Christian tradition are used in many of the tweets. However, in order to adapt to the medium of usage, they are formulated and structured in a new way. This embodies the polarity of stasis, on the one hand, and specific renewing development, on the other hand.

Conclusion

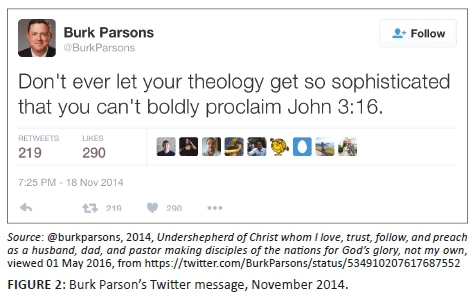

Drawn from the empirical Twitter data in this study, the above Twitter message (Figure 2) from an American preacher, Buck Parsons (@burkparsons 2014:n.p.), expresses one of the key aspects of this research. The fact that Burk Parsons is not only an internationally well-known theologian but also that his message can be read and heard globally via Twitter serves as an apt point of departure for this last reflective12 chapter. Although this message shows signs of academic theology and is most likely directed to a church audience, it is formulated in such a way that it is also accessible, intelligible and meaningful to other users of Twitter. Directly linked to nuances in my own autobiographical narrative, I focused on the analysis of the communication of Christian motifs on Twitter. In addition, this tweet also expresses specific Christian motifs such as those embodied in the terms 'theology' and 'preaching', but refers directly to the well-known biblical text John 3:16.

On the basis of the perspectives derived from the research, the project is placed within the bigger movements and changes in the world as a highly relevant endeavour. These descriptions are also relevant at a time when practical theology emphasises the importance of various forms of lived religion. As mentioned earlier, the research project also stands central in my own personal realisations and search for the discovery of possible new theological meaning and relevance. In this respect, the reflection on the practice of theological Twitter has also newly informed the praxis of my own identity as practical theologian and researcher.

In the research project, I traced and analysed the prevalence, use and communication of Christian motifs on Twitter, with the aim of depicting descriptions of 'aspects of everyday life that have hitherto not been readily made public' (Zappavigna 2012:37). The study thus embodies a wider focus for me than simply the traditional domain of the professional theologian, because I am particularly interested in investigating the communication of Christian motifs on all levels of the Twitter domain. In the process of negotiating the possible meaning of this research endeavour, I concur with Ganzevoort (2014:4) that the new theologian is called to be not so much a representative of tradition, but rather an interpreter, translator or guide who, in conjunction with others, seeks links to greater meaning. Within this orientation, my earlier research concern for a relevant contextual theology is addressed.

Acknowledgements

Some of the work in this article stems from Jan A. van den Berg's thesis, entitled 'Tweeting God: A practical theological analysis of the communication of Christian motifs on Twitter', presented in fulfilment of the requirements for a PhD degree at The University of Queensland in 2018.

Competing interests

The author has declared that no competing interests exist.

Author(s) contributions

I declare that I am the sole author of this research article.

Ethical consideration

This article followed all ethical standards for a research without direct contact with human or animal subjects.

Funding information

The funding of the research was supported by an award from the National Research Foundation (NFR) of South Africa.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the author.

References

Astley, J., 2002, Ordinary theology, looking, listening and learning in theology: Explorations in practical, pastoral and empirical theology, Ashgate, Hampshire. [ Links ]

Astley, J., 2013, 'The analysis, investigation and application of ordinary theology', in J. Astley & L.J. Francis (eds.), Exploring ordinary theology: Everyday Christian believing and the church, Kindle edn., pp. 1-13, Ashgate, Surrey. [ Links ]

Ballard, P., 2012, 'The use of Scripture', in B.J. Miller-McLemore (ed.), The Wiley-Blackwell companion to practical theology, pp. 163-172, Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford. [ Links ]

Boyd, D., Golder, S. & Lotan, G., 2010, 'Tweet, tweet, retweet: Conversational aspects of retweeting on Twitter', 43rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, IEEE, Advancing Technology for Humanity, Kauai, January 05-08, 2010, pp. 1-10. [ Links ]

Bull, M., 2016, Birds of the air: Theological Twitter, BibleMatrix, Sydney. [ Links ]

Byers, A., 2013, Theomedia: The media of God and the digital age, Cascade Books, Eugene, OR. [ Links ]

Campbell, H.A. & Teusner, P.E., 2011, 'Religious authority in the age of the Internet', in Virtual lives: Christian reflection, pp. 59-68, Baylor University Press, Waco, Texas, viewed 12 July 2017, from https://www.baylor.edu/content/services/document.php/130950.pdf. [ Links ]

Campbell-Reed, E.R. & Scharen, C., 2013, 'Ethnography on holy ground: How qualitative interviewing is practical theological work', International Journal of Practical Theology 17(2), 232-259. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijpt-2013-0015 [ Links ]

Carr, N., 2010, The shallows: How the internet is changing the way we think, read and remember, Atlantic Books, London. [ Links ]

Cilliers, J., 2009, '"Fides quarens societatem", Praktiese teologie op soek na sosiale vergestalting', Tydskrif vir Geesteswetenskappe 49(4), 624-638. [ Links ]

Cheong, P.H., 2014, 'Tweet the message? Religious authority and social media innovation', Journal of Religion, Media and Digital Culture 3(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1163/21659214-90000059 [ Links ]

Díez Bosch, M., Soukup, P., Micó Sanz, J.L. & Zsupan-Jerome, D. (eds.), 2017, Authority and leadership: Values, religion, media, Ramon Llull University, Barcelona. [ Links ]

Ganzevoort, R.R., 2004, 'What you see is what you get', in J.A. Van der Ven & M. Scherer-Rath (eds.), Normativity and empirical research in theology, pp. 17-34, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Ganzevoort, R.R. 2006, De hand van God en andere verhalen: Over veelkleurige vroomheid en botsende beelden, Meinema, Zoetermeer. [ Links ]

Ganzevoort, R.R., 2014, 'Hoe leiden we anno 2014 goede theologen op?', Handelingen 41(3), 20-30, viewed 07 September 2015, from http://www.ruardganzevoort.nl/pdf/2014_Opleiden_Theologen.pdf. [ Links ]

Graham, E.L., 2013, 'Is practical theology a form of "Action Research"?', International Journal of Practical Theology 17(2), 148-178. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijpt-2013-0010 [ Links ]

Graham, E.L., 2017, 'On becoming a practical theologian: Past, present and future tenses', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 73(4), a4634. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v73i4.4634 [ Links ]

Grant, B., 2016, The aphorism and other short forms, Routledge, New York. [ Links ]

Horner, Z., 2014, 'How Christian leaders interact with the Twitter', Print/Online Journalism, Elon University, Elon, NC. [ Links ]

Lyall, D., 2000, 'Pastoral action and theological reflection', in D. Willows & J. Swinton (eds.), Spiritual dimensions of pastoral care: Practical theology in a multidisciplinary context, pp. 53-58, Jessica Kingsly Publishers, London. [ Links ]

Lynch, G., 2005, Understanding theology and popular culture, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford. [ Links ]

Migliore, D.L., 1991, Faith seeking understanding: An introduction to Christian Theology, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Moschella, M.C., 2012, 'Ethnography', in B.J. Miller-McLemore (ed.), The Wiley-Blackwell companion to practical theology, pp. 224-233, Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford. [ Links ]

Newby, G.D., 2008, 'The use of electronic media in the study of sacred texts', in P. Antes, A.W. Geertz & R.R. Warne (eds.), New approaches to the study of religion 2, Textual, comparative, sociological, and cognitive approaches, pp. 45-47, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin. [ Links ]

Newton, C., 2017, Twitter just doubled the character limit for tweets to 280, Tweets twice as big roll out in a global test, viewed 17 October 2017, from https://www.theverge.com/2017/9/26/16363912/twitter-character-limit-increase-280-test. [ Links ]

Osmer, R., 2008, Practical theology: An introduction, Wm B. Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Reader, J., 2008, Reconstructing practical theology: The impact of globalization, Ashgate, Hampshire. [ Links ]

Snowden, C., 2012, 'From epigrams to tweets', Asiatic 6(2), 81-95. [ Links ]

Stoehr, A., 2016, 'Normativity as a social resource in social media practices', in M.M. Lian, M.S. Karrebaek & J.S. Møller (eds.), Everyday language, collaborative research on the language use of children and youth: Trends in applied linguistics, n.p., Mouton De Gruyter, Berlin. [ Links ]

Sweet, L., 2012, Viral: How social networking is poised to ignite revival, Kindle edn., Waterbrook Press, Colorado Springs, CO. [ Links ]

Sweet, L., 2014, Twitter Theology: 5 ways Twitter has changed my life and helped me be a better disciple of Jesus, viewed 28 April 2014, from http://www.leonardsweet.com/article_details.php?id=55. [ Links ]

Swinton, J. & Mowat, H., 2006, Practical theology and qualitative research, SCM Press, London. [ Links ]

Tanner, K., 2002, 'Theological reflection and Christian practices', in M. Volf & D.C. Bass (eds.), Practicing theology: Beliefs and practices in Christian life, pp. 228-244, Wm B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Turner, B.S., 2012, 'Religious authority and the new media', Theory, Culture & Society 24(2), 117-134. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276407075001 [ Links ]

Van den Berg, J.A., 2018, 'Tweeting God: A practical theological analysis of the communication of Christian motifs on Twitter', Unpublished PhD thesis, The University of Queensland, Brisbane. [ Links ]

Ward, P., 2017, Introducing practical theology: Mission, ministry and the life of the church, Baker Academic, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Zappavigna, M., 2012, Discourse of Twitter and social media, how we use language to create affiliation on the web, Continuum International Publishing Group, London. [ Links ]

@catholicnewssvc, 2015, Catholic News Service is a leader in religious news. Our mission is to report fully, fairly and freely on the involvement of the church in the world today, viewed 04 July 2017, from https://twitter.com/catholicnewssvc?lang=en. [ Links ]

@burkparsons, 2014, Undershepherd of Christ whom I love, trust, follow, and preach as a husband, dad, and pastor making disciples of the nations for God's glory, not my own, viewed 01 May 2016, from https://twitter.com/BurkParsons/status/534910207617687552. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Jan A. van den Berg

vdbergja@ufs.ac.za

Received: 15 May 2019

Accepted: 29 July 2019

Published: 19 Nov. 2019

Note: HTS 75th Anniversary Maake Masango Dedication

1 . Completed PhD research project with the title 'Tweeting God: A practical theological analysis of the communication of Christian motifs on Twitter' (Van den Berg 2018).

2 . In social media, the hashtag sign(#) is used to semantically group posts on platforms such as Twitter, Facebook and Instagram.

3 . By theological language, I mean all possible ways to express the embodiment of Anselmus' classical definition of theology, namely 'fides quaerens intellectum' (Migliore 1991:2). For further explanation of this in the description of a 'lived religion' (Ganzevoort 2006:151), see the embodiment of a 'fides quaerens societatem' (faith in search of social embodiment) (Cilliers 2009:634).

4 . The emphasis on 'ordinary theology', 'espoused theology', 'implicit religion' and 'lived religion' echoes the concern of Astley in taking 'seriously the beliefs of "non-theologically educated" churchgoers and other Christian believers, and of those outside the churches', as documented in his seminal work 'Ordinary Theology' (2002:viii). In addition, Pete Ward (2017:57) has indicated that 'Lived religion has developed as a way of speaking about religion that is not primarily cognitive or doctrinal in orientation'.

5 . Across all 35 keywords observed in the period from 01 September 2013 to 18 May 2015, a total of 1.1 billion global posts were collected on Twitter, with a daily average of 1.7 million posts. Analysed content trends throughout each year tended to spike in fairly predictable periods around Christian holidays, the most predominant being Christmas and Easter, with a nearly double average volume over those periods. An analysis of the words used in the 1.1 billion tweets shows that the most popular words are 'God', 'church', 'Jesus' and 'faith'. These words are often used in conjunction with positive words such as 'life', 'thank you', 'please', 'Lord', 'always' and 'believe'. However, these words are also used in conjunction with negative words to convey frustration online. Twitter users often use hashtags (Twitter keywords) to tag content in their tweets. The top tags used are #jesus, #god, #faith, #bible and #christian. This indicates a clear intent to express specific messages regarding Christianity.

6 . Twitter announced that up to 280 characters can be used for Twitter messages (Newton 2017:n.p.). This number of characters further challenges the search for an aphoristic theology described in the research. However, 280 characters are still much less than the extensive theological arguments often used in professional articles and books.

7 . See also the examples provided by Cheong (2014) and Bull (2016).

8 . A good example of this can be found in the contribution of Stoehr (2016:n.p.) regarding the fluid normativity associated with writing and spelling in social media practices.

9 . The author prefers her name and surname not to be in capital letters.

10 . The 'like' function on Twitter provides for a creative way in further enforcing the impact of a specific message, contributing to the creation of a specific normativity within an online community.

11 . In the edited volume, Authority and leadership: Values, Religion, Media by DíezBosch et al. (2017), it is confirmed that authority and leadership within an Internet-driven culture are dynamically created and facilitated in a participating and interpretive manner.

12 . The reference to 'reflection' is presented in sensitivity with regard to the many nuances of 'theological reflection' and 'reflexivity' (Reader 2008:14).