Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

HTS Theological Studies

versão On-line ISSN 2072-8050

versão impressa ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.75 no.4 Pretoria 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v75i4.5060

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

A dangerous pedagogy of discomfort: Redressing racism in theology education

Gordon E. Dames

Department of Philosophy, Practical and Systematic Theology, University of South Africa, South Africa

ABSTRACT

This article aims to illustrate how racism could be addressed. Three pedagogies - a dangerous pedagogy as courageous dialogue, a pedagogy of discomfort and a critical pedagogy - are presented as examples to reframe the issue of racism. The contribution of James Cone is applied as a broad descriptive theoretical framework. Cone's views in this article resonate with the history of contemporary racism in South Africa and will therefore be juxtaposed by the contribution of South African theologians. A fourth pedagogy, namely, a pedagogy of freedom and healing, is introduced to address gaps in the first three pedagogies. The objective is to realise freedom or healing between people of different races.

Introduction

The concept dangerous pedagogy as mentioned in the article title draws on the notion of a dangerous memory of marginalised people in society (Botman 2000:208). Gutiérrez refers to dangerous memory as the proletariat's resistance to the dehumanising effects of suffering (in Graham & Poling 2000:164). This notion of a dangerous pedagogy is particularly relevant here as it encapsulates Cone's (2002) conceptualisation of Black Theology for theology education - which will serve as the basis for this article. This article is specifically inspired by the recent death of James Cone (Brown Douglas, Jones & Warnock 2018). It is also in honour of the life and work of Maake Masango. Masango's (2011:2) recollection of his own daughter's painful experience during apartheid in South Africa illuminates the pedagogical problem of public education in general and theological education in particular:

She was attending kindergarten at a so called 'White school'. One day she came home and told a painful story of having been called names at school. She had fought with and hurt the other child who was White. My wife and I read a letter from her teacher in which was described what had happened. My wife asked her to sit down and then said to her: Because she called you dirty and ugly names, it does not make you what she believes you are … to fight, that is your decision. But don't fight because you are called Black and African. The truth of the matter is that you are Black and you are of African descent. Anywhere you go for the rest of your life you are going to be called that. You should feel proud when someone says to you that you are a black African. (p. 2)

Masango (2011) was fixated on the negative name-calling of his daughter and asked his wife why she had responded in that particular way. His wife answered:

If I had responded to the negative aspect, I would have reinforced Tshepo's anger and violence. … For me, it is okay when others call her Black and African. That is what she is. If I had responded negatively, I would have brought in my own negativity and she would have responded in a negative way. I do not want to teach her to drink that kind of poison. Negative behavior breeds negativity. I rather want to redirect her energy in a positive way. (p. 2)

This story, especially his wife's response, taught Masango a life lesson: 'When striking or fighting back, one engages in one's own self-hatred' (2011:2). This brings us to the following question: what type of pedagogy can redress racism in theology education?

Contemporary occurrences of racism

Evidence below indicates that it is almost as if we are reliving the vicious and evil past of racism in South Africa today:

In post-apartheid South Africa, sixteen years into multiparty democracy, we can pause to ask whether blacks are really free. The answer is negative, because apparently there is still what Hopkins (1987:xiv) called the 'multilayered reality of black oppression' through subtle and overt racism. … [Ours is] a predominantly patriarchal society [where] the high prevalence of HIV/AIDS [in] black women in particular [reflects their lack of power and that they] bear the brunt of racial, gender, and class marginalisations. (Chimhanda 2010:437)

Despite non-racial constitutional pledges and legislation prohibiting racism, racist stereotyping continues to circulate in explicit and implicit criticism of the activities, politics and ideas of black people. (Durrheim et al. 2011:32)

Despite the struggle for human rights in South Africa, the release of Nelson Mandela from prison in 1990 and the adoption of the new constitution in 1996, we have not seen the death of racism. Powerful forms of resistance to the change in the status quo are prevalent - this resistance is a modern form of racism. (Batts 2013:89)

Within the South African context a recent incident revealed the extent of the prevalence of racism in our society. Vicki Momberg was sentenced to an effective two years in prison. … Momberg's was the worst crimen injuria case [recorded since 1994]. She was found guilty on four counts of crimen injuria on November 3 in connection with her verbal tirade against black people during which she used a historically derogatory racist term for black people at least 48 times. (Pijoos 2018)

The institutionalised and systemic nature of racism, white supremacy and neo-black supremacy is a destructive cancer at the core of 'our "liberated" society' (Kgomosotho 2018:33). Recent violent protest action from Bonteheuwel to Westbury illustrates how the so-called mixed race people are revolting against black privilege and systematic economic, sociopolitical, cultural and psychological disempowerment: 'We can see how black communities are developing‚ but in our communities nothing happens‚ and we must just be content and accept how this government is leaving us behind' (Njilo 2018):

Racism is about economic [business], cultural and political power and oppression perpetrated through slavery, colonisation and apartheid, when racial slurs and assaults were but an expression or affirmation of this power dynamic. […] These racial slurs and assaults undoubtedly injure people's very sense of humanity, their dignity, often in ways that are overlooked. Racism is nauseating, particularly in relation to our history of racial subjugation and the continued dehumanisation of black bodies. (Kgomosotho 2018:33)

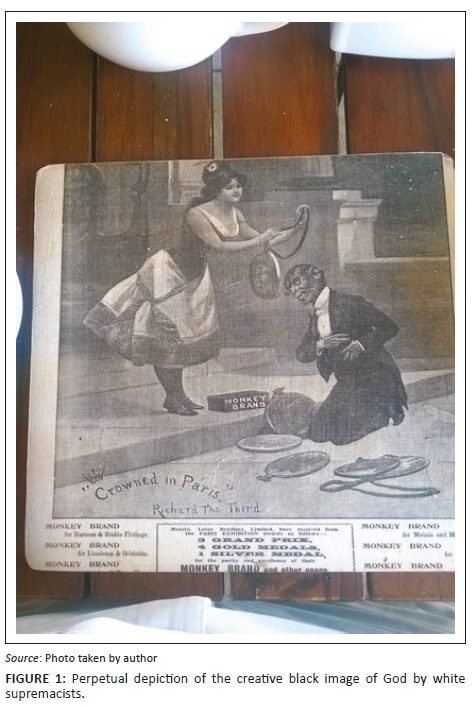

For example, I took the photo in Figure 1 of a placemat on one of the tables at a farmstall between Springfontein and Colesburg on the N1 (South Africa) earlier this year. A growing number of similar artefacts at farmstalls can be found along the provincial and national roads of South Africa. Systemic racism and any form of supremacy are an injustice to humanity and illegitimate in South Africa.

Kgomosotho (2018:33) rightly ask the question: 'To what extent is criminalisation effective in addressing racism at its very core? How far will we go by hunting down the "bad" or "extreme" racist?'

Most white people may still believe it impossible for a white person to go to prison for the racial abuse or killing of a black person (Boesak 2009:264). Note, for instance, the following critique:

They who are responsible for the dividing walls of hostility, racism and hatred, want to know whether the victims are ready to forgive and forget - without changing the balance of power.

They want to know whether we have any hard feelings toward them, whether we still love them, even though we are oppressed and brutalised by them. What are we to say to people who insist on oppressing us but get upset when we reject them? (Cone 1975:226)

We argue here that the impunity of racism exacerbates the dangerous lives of subjugated and oppressed people. The use of the concept 'dangerous' is derived from dangerous memories that constitute a history of resistance and struggle for human dignity against inhuman oppression (Welch in Graham & Poling 2000:164). These recurring memories of racism can be defined as modern racism. According to Batts (2013:89-90), modern racism pertains to beliefs related to abstract ideological symbols and symbolic behaviours that black people are demanding for change in the racial status quo, whilst white people continue to believe that black people are inferior. The result of such belief systems is the fuelling of 'violent accusations of racism, conflict, emotive language and racial stereotyping' (Durrheim et al. 2011):

Race intrudes into and disrupts our lives. … Race troubles us by structuring how we live and by thus shaping our experiences. Race trouble can thus be defined as a social psychological condition that emerges when the history of racism infiltrates the present to unsettle social order, arouse conflict of perspectives and create situations that are individually and collectively troubling. (p. 27)

We cannot ignore that there are broader structural, political and economic forms of racism. Because of limited space, an in-depth analysis is not possible here (Durrheim et al. 2011:27-28).

Gustavo Gutiérrez (2014:xxii), as a theologian of liberation theology in Latin America, raises alarm that racism is a major challenge to the Christian community in his country. He holds that theologians in Latin America are 'only now beginning to respond' to this evil:

The situation of racial and cultural minorities and of women among us is a challenge to pastoral care and to commitment on the part of the Christian churches; it is therefore also a challenge to theological reflection. (p. xxii)

Pui-lan (2005:152), a North American feminist theologian, concurs with Gutiérrez's (2014) critique. She further expands on the debate by reflecting on the importance of feminist theology in engaging racism, cultural oppression and environmental justice (Pui-lan 2005:152). Pui-lan (2005:21-22) refers to Traci West's exposition of colonialisation as a unit of analysis for Afro-American internalisation of Euro-American racism and the psychosocial condition of black people. The authors propose a link between colonialisation and Euro-American racism (West in Pui-lan 2005:21-22). White people inevitably define black reality in terms of their social, political and economic interests. However, black reality is the sum total of African psychosocial crises (Motsi & Masango 2012:7). Masango's (2014:1) postulation of how economic systems crush the poor speaks from his father's teaching and disposition against inhuman oppression: 'Once you are educated, no one in this system of oppression can take that away from you'. Another unit of analysis used in the race debate is that of religion, as pointed out by Cone (1975:2): 'They tried to make us believe that God created black people to be white people's servants'. In the South African context, Kritzinger (1990:58), a white South African theologian, calls for a white liberation to disengage from their colonial mentality by decolonialising their white consciousness.

The aforementioned realities illustrate how racism could be addressed. Three pedagogies as discussed below may offer insights to reframe the issue of racism. To this end, the contributions of James Cone (2002) are applied as a broad descriptive theoretical framework. Cone's views in this article resonate with historical and contemporary racism in South Africa and will therefore be juxtaposed to the contribution of South African theologians. The hypothesis of this article is that Masango's pre- and post-apartheid theological career and life experience correlates with Cone's struggle for social justice, human dignity, liberation and the affirmation and actualisation of black identity and humanity (cf. Wolterstorff 2004:136-137). A fourth pedagogy will be introduced later that addresses a limitation in the first three pedagogies. The objective is to search for a Masango-type pedagogy (2011) to realise freedom or healing between people of different races.

Pedagogy in this article refers to transformation and liberation and deals with contentious issues such as human dignity, social justice, solidarity with the marginalised to redress violence, xenophobia and racism (Nipkow 2003:4-5). Recurring traumatic violence in Africa complicates and diminishes human and cultural agency and resources (Motsi & Masango 2012:7). To this end, Chimhanda (2010:441) draws on Black Theology, particularly as it pertains to education and empowerment 'for self-knowledge, self-affirmation and self-actualisation for responsible black participation in leadership, economic growth and multicultural living'.

Three constructive pedagogies to address racism

The principles of each of the following (general) pedagogies will be viewed in relation to the different life phases or theoretical perspectives of Cone (2002). These pedagogies reflect the essence of a dangerous pedagogy as they seek to address distorted views on race. It is hoped that Cone's contribution may provide rich cognitive and experiential insight on how theology education should be harnessed to engage racism in the modern world. The aim is not to present a critical critique of pedagogy in relation to Cone or Masango, rather to suggest indicators for a transformed pedagogy of theology to redress racism. The latter will not be discussed here. A comprehensive perspective on contextual transformational theological education was done previously (Dames 2014; 2016).

Firstly, dangerous pedagogy as courageous dialogue is an attempt to break down racial tension and ignorance so that dialogue partners can share this knowledge and others, or passive partners, can learn and grow from the experience. It is the building of mutual understanding to foster equity and challenge overt and subtle racial conflict (Singleton & Curtis 2006:53). Personal engagement, honesty, endurance and persistence in dialogue about race in educational institutions require a commitment for courageous dialogue: to stay engaged, experience discomfort, speak truth to power, and expect and accept non-closure. However, educators need mainly to reflect and act on their own racial consciousness by embracing the dangerous memory of the marginalised (Singleton & Curtis 2006:53).

Secondly, a pedagogy of discomfort creates understanding of how norms and differences are developed (Boler & Zembylas 2003:111). Both educators and students are empowered to move outside of their comfort zones - their cultural and emotional positions occupied more by virtue of hegemony1 than by choice. Thus, 'a pedagogy of discomfort recognises and problematises the deeply embedded cultural and emotional dimensions that frame and shape daily habits and unconscious complicity with hegemony' (Boler & Zembylas 2003:111). The aim is to explore the ways in which dominant values and assumptions in our daily habits and routines are enacted and embodied (Boler & Zembylas 2003:111). Critical enquiry at a cognitive and emotional level challenges members of both the dominant and marginalised cultures to re-examine the internalised hegemonic values in curriculum and media that serve the interests of the ruling class (Boler & Zembylas 2003:12;117). Hegemony and liberal individualism disempower the ability to recognise how institutionalised sexism, racism and homophobia affect us and others (Boler & Zembylas 2003:117). Therefore, educators and students should engage in critical thinking and explore habits, relations of power, knowledge and ethics that determine the conduct of educators and students. An important aspect in racial redress 'is the recognition of the multiple, heterogeneous, and messy realities of power relations as they are enacted and resisted in localities, subverting the comfort offered by the endorsement of particular norms' (Boler & Zembylas 2003:131).

Thirdly, critical pedagogy based on critical theory helps to analyse oppressive practices that cause social inequalities through praxis and power, as experienced by the marginalised in society (Zimmerman, McQueen & Gwendolyn 2011:16). Critical pedagogy strives to transform education and society through reflection and action, within the classroom and through academic theorising (Zimmerman et al. 2011:16). The complexity and contradictions of individuals, and the society in which they exist, are explored (Zimmerman et al. 2011:16). Critical pedagogy is inspired by education as the practice of freedom towards a more just and less oppressive society (Zimmerman et al. 2011:20). Subjectivities shape our being human, but our collective situatedness in terms of context, race, class and gender will always influence our perspective (Zimmerman et al. 2011:20).

The above overview of three pedagogies for the redress of racism serves as a basis for drawing analogies for the South African context. According to Hopkins (in Chimhanda 2010):

The Black Theology of South Africa and the Black Theology of North America have one common foundational focus, that is, the liberation from racism. … Black Theology's agenda is to explore black consciousness and power to liberate the black poor fully, culturally, politically and spiritually. (p. 435)

The African-American black theology pedagogue: James Cone (2002)

We shall draw more specifically on the life and work of the renowned African-American black theologian James Cone (2002) for a more focused analysis as his work exemplifies aspects of the aforementioned three pedagogies. Drawing on Bonino (2004:131 in Steyn and Masango 2011:3) holds that the relevancy of theological education rests on the context of theology in action. Such a theological praxis should be liberating if it is to affirm the people it seeks to help (Steyn & Masango 2011:4).

Racialised childhood context: A pedagogy of discomfort

Cone's childhood was shaped by a racialised rural community where he struggled with the paradox of the 'persistent racial tension with white people and lingering ambivalence in his feelings towards blacks' (2002:1). Bearden, Arkansas, shaped his identity and life experience as black and Christian as it was characterised with structural segregation on all levels of society. As he so profoundly states, he only encountered racial interaction 'at the back door of homes of white people' (Cone 2002:1; cf. Baloyi 2010). White people regarded the black people as 'worthless human beings' (2002:1). Segregation of churches based on the colour of people's skin bothered him the most. He holds that:

[i]n Bearden, like the rest of America, Sunday was the most segregated day of the week, and 11:00 am the most segregated hour. Black and white Christians had virtually no social and religious dealings with each other. (Cone 2002:2)

In South Africa, the apartheid government employed ethnic mobilisation (the Afrikaner nation) to produce nationalism of exclusion: 'One of the mechanisms of exclusion was the imposition of the pass laws, which were very oppressive and restrictive to South African people, especially women' (Segalo & Mothoagae 2015:234):

The history of segregation, racism, apartheid (apartness) and the formation of the Bantustans in South Africa point to … the assertion by Machery and Faucher, that, race membership is culturally transmitted and the concept thereof emerges also from one's social environment. Racism in South Africa, one could argue, was constructed on the basis of biology, ethnicity and social identity; and undergirded by a white supremacists notion of national identity in terms of a narrow identity, ethnicity and spirituality. (p. 235)

Thus, Cone's racialised experience informed his understanding of how racial norms and differences in Bearden were developed, and propelled him outside his 'inscribed cultural and emotional comfort zone to redress racial hegemony'.

His experience of discrimination and white supremacy raised the following critical questions during his childhood: 'What kind of Christianity is it that preaches love and practices segregation?' (Cone 2002:3). Despite these experiences, he never felt inferior because of what white people said about him or other black people - because of an 'unassailable and monumental dignity' projected by his family. His living philosophy was: 'You can only be destroyed by believing that you really are what the white world calls a nigger'. This was his 'experience of surviving with dignity in a society that did not recognise black humanity' (Cone 2002:3).

Hence, Cone's experience helped him to recognise and problematise the 'deeply embedded cultural and emotional dimensions' that formed and shaped the unconscious complicity with hegemony in his hometown.

The black church-racialised context: A pedagogy of discomfort

According to Cone (2002:4), he struggled to grasp how white people reconciled racism with their Christian identity. The passive or uncritical faith in many black churches posed an even bigger problem to him. Cone's (2002) experience could easily be related to the black experience in South Africa (cf. Baloyi 2010).2 Black churches or members not only tolerated anti-intellectualism and moral decay in South Africa (cf. Chimhanda 2010)3 but often promoted it just as white people tolerated and promoted racism (Cone 2002):

He was deeply troubled by the anti-intellectualism that permeated many aspects of the ministry in the black church. The search for a reasoned faith in a complex and ever changing world was the chief motivation that led him to study theology. Critical reflection or study of the Bible, history, theology and the practice of ministry led him to explore its meaning for different social, political and cultural contexts, past and present. (p. 4)

This experience prompted him to reflect critically on the meaning of faith in and during those dark racist times and situations in which black people were forced to live (Cone 2002:4). As with similar liberational experiences, the Civil Rights and Black Power movements in the US during the 1960s challenged his initial theological premise. He discovered the disparities and limitations in his Eurocentric theological education:

The curriculum at theological institutions did not deal with questions that black people were asking as they searched for the theological meaning of their fight for justice in a white racist society. And as individuals and isolated students within a demanding educational system, neither I nor the other token number of black students had the intellectual resources to articulate them. (Cone 2002:5)

This realisation exposed the implausibility of 'the doctrines of the faith as they had been re-interpreted by Eurocentric colonisers and white racists in the United States' to his struggling black community, hence his search for a new theological identity - which reflected the life, history and culture of African-American people (Cone 2002:5). He would ultimately create a Christian theology 'out of the black experience of slavery, segregation and the struggle for a just society' (Cone 2002:5). He had finally discovered his theological voice, his black theological consciousness - mainly through reading the theologies of Martin Luther King Jr and Malcom X. The cultural and political insights of Malcom and Martin transformed his analysis and articulation of theology and race. He used these to challenge his white professors 'to exorcise the racism in their theologies' (Cone 2002:5).

As highlighted by Chimhanda (2010:349), when we consider the South African context, we note that in the new South Africa a society where there is a black and/or white divide and where racism is still evident:

[… B]ut as Du Toit (2009:28) points out, neither side openly owns to it in the new situation where apartheid is openly denounced as illegal. However, it can be said that subtle racism is legalised in policies like BEE, a situation that Black Theology as critical instrument needs to interrogate. (Chimhanda 2010:439)

Hence, life in Bearden forged Cone's critical intellectual and emotive critique that challenged both members of the dominant and marginalised cultures to re-examine their structural and internalised values. Through critical thinking he explores the multiple habits, power relations and false comfort zones that serve the hegemonic values and interests of the ruling class.

Racialised theological education: Critical pedagogy

Cone juxtaposed his theology based on the black experience, against abstract theological jargon of his white colleagues at Union Theological Seminary (Cone 1975:3, 6). He firmly maintained that black theologians must approach theology first and foremost in terms of the black experience, Church and society dominated and subjugated by white people (Cone 1975:5):

I was transformed from a negro theologian to a black theologian, from an understanding of theology as an analysis of God-ideas in books to an understanding of it as a disciplined reflection about God arising out of a commitment to the practice of justice for the poor. The turn to blackness was a deep metanoia experience - truly spiritual, radically transforming my way of seeing the world and doing theology. (Cone 2002:6)

Blackness offered him new theological lenses, enabling him to transcend white theology and empowered him with critical reflection to critique white academic values. Apart from the Bible, the African-American history and culture became the most insightful source of reflection in his theology. Blackness inspired his development of black theology for poor black people and not for the privileged white theological establishment (Cone 2002:6).

However, in Africa, a different reality is revealed. Theological education of black ministers is being dictated and determined by white capital:

Raising challenging issues during training is not tolerated because critical thinking is believed to be the work of the devil and inimical to the faith of the individual. Books of 'liberal theologians' do not appear on reading lists. The clergy then come out of training devoid of a critical approach to their ministry. The training curriculum has not been geared to the African cultural milieu, hence the clergy cannot contextualise. (Waruta & Kinoti in Baloyi 2010:427).

Baloyi (2010:427) concludes that these black theologians will oppose any form of African culture and the Africanisation of Christianity by protecting the white doctrine of their education (Waruta & Kinoti in Baloyi 2010:427). This is a tragic reality that requires redress. However, for Cone (2002), the theological premise of the black experience reshaped the theodicy question in a profound and challenging way:

It forced me to search deep into a wellspring of blackness, not for a theoretical answer that would satisfy the dominant intellectual culture of Europe and the USA, but rather for a new way of doing theology that would empower the suffering black poor to fight for a more liberated experience. (p. 6)

Liberal approaches of oppression as abstract ideas by white liberals should be transformed into concrete political action (Macedo 2001:xxviii). Transformative action could be realised when black and white people become interlocutors in and through concrete reciprocal learning and action about each other's cultural and political backgrounds (Masango 2011:3; Tfwala & Masango 2016). Cone's (2002:7) response was forceful against the racism in theology, the churches and the broader society, resulting in his book Black Theology and Black Power (1969).

An overview of Cone's biography reveals his ability to employ critical theory to analyse the oppressive racial and social injustices through reflection on and action in hegemonic and marginalised praxes in society.

Similarly in the South African context, we can draw from Cone's (2002) work and use critical theory to analyse our context and experiences. Following Cone's (2002) directive, we now turn our gaze towards a critical reflection of theology framed by a white, racialised world view.

Racialised white theologians in context: Critical pedagogy

Cone (1975:6) defines the theology education of white theologians as theological bankruptcy. In the same vein, Freire (2001:100) refers to intellectuals engaging in highly authoritarian pedagogico-political practice. In search of teaching practices with the virtue of coherence, Freire (2001:100) warns against the danger of the so-called progressive teachers' racist attitudes. They are basically not educated to deal with the reality of black lives, particularly to grasp the dialectic of black history and culture (Cone 1975:6). To this end, Kritzinger (1990:55), in South Africa, calls for liberation towards humanity and acknowledges that white people are unable to speak about human liberation because of racist societal structures. He challenges the privileged positions that white people occupy and calls for the disengagement of their innocent, universal or neutral white theology that does not seriously calibrate the concrete situation of white people theologically (1990:55). Their inability to recognise and accept accountability for the existential reality of black oppressed people is a pseudo-innocence (Boesak 1977:8). The appalling silence of white theologians on racism across the world is of grave concern. The absence of an emphatic critique on or silence about racism in South Africa is highlighted by various theologians in the book, Christian in Public: Aims, Methodologies and Issues in Public Theology (2007), in honour of Beyers Naudé - icon of the liberation struggle against the apartheid racist regime. This book encapsulates this uneasy silence (ed. Hansen 2007). Graham and Poling (2000:164) regard such silence as the silencing of the oppressed from official histories and theologies:

Whereas this silence has been partly broken in several secular disciplines, theology remains virtually mute. … with few exceptions, [white theologians] write and teach as if they do not need to address the radical contradiction that racism creates for Christian theology. … White images and ideas dominate the religious life of Christians and the intellectual life of theologians, reinforcing the 'moral' right of white people to dominate people of colour economically and politically. White supremacy is so widespread that it becomes the 'natural' way of viewing the world. (Cone 1975:133)

Cone consequently wonders whether racism is 'so deeply embedded in Euro-American history and culture that it is impossible to do theology without being anti-black'.4 The same ideological question in the post Jewish Holocaust featured 'where Christian theologians were forced to ask if theology was no longer possible without being anti-Semitic' (Cone 2002:7). The holocaust scenario resonates with a white South African theologian Nico Smith's postulation that racism is not so much a political or theological challenge, although it truly is, but with an instinctive observation that his own people are determined to hold on to hegemonic power at the cost of humanity (Balcomb 1990:44): Racism lives off hegemonic power and perpetuates cultural and epistemological inferiority (Koopman 2008 in Dames 2014:160):

When the past and contemporary history of white theology is evaluated, it is not difficult to see that much of the present negative reaction of white theologians to the Black Christ is due almost exclusively to their whiteness, a cultural fact determines their theological inquiry, thereby making it almost impossible for them to relate positively to anything black. (Cone 1975:133)

Should we regard Christianity then as a tool for exploiting the poor (Cone 2002:10)? Local theologian Chimhanda proposes that Black Theology should be used as a critical tool to disseminate primary causal factors in the marginalisation of (black) people. She also emphasises the importance of exploring authentic black empowerment (Chimhanda 2010:438). In the same vain, Masango (2011:2) calls for the nurturing and empowerment of the marginalised and voiceless towards positions and dispositions of greater power. Cone (2002:10) opines that race criticism as the integrity of Christian theology is as crucial as any scientific critique:

How do we account for such a long history of white theological blindness to racism and its brutal impact on the lives of African people? White supremacy shaped the social, political, economic, cultural and religious ethos in the churches, the academy and the broader society. Seminary and divinity school professors contributed to America's white nationalist perspective by openly advocating the superiority of the white race over all others. … As long as religion scholars do not engage racism in their intellectual work, we can be sure that they are as racist as their grandparents, whether they know it or not. (p. 8)

Hence, America's and Africa's violent racist crime against black people is being ignored by white theologians as if it does not exist (Cone 2002:8-9). Racism is deeply embedded in American and Eurocentric history and culture - ignorance begot an injustice against black people (Cone 2002):

Through their control of the media, as well as their control of the religious, political and academic discourse, 'they're able', as Malcolm put it, 'to make the victim look like the criminal and the criminal look like the victim'. (p 10)

White theologians when dealing with the problem of theodicy (God and suffering) almost never regard racism as the core issue in their analysis of how evil opposes the Christian faith (Cone 2002:10; cf. ed. Hansen 2007). Although racism is so prevalent and violent in American life, it remains absent in white theological discourse. A contrary scenario may help them to 'discover how deep the cancer of racism is embedded not only in the society but also in the narrow way in which the discipline of theology is understood' (Cone 2002:10). There have been some critical thinkers in South Africa, white theologians like Nico Smith, Beyers Naudé, Klippies Kritzinger and Denise Ackermann, who have sought to be different and act in spite of their white privileged theological background and cultural heritage (Balcomb 1990:45; Hofmeyr, Kritzinger & Saayman 1990). A more detailed reference to the works of these theologians is given in the rest of this article. These theologians have embodied Boesak's (1977:9) postulation of Farewell to innocence that liberal white people espouse by their total identification with what the oppressed are doing to actualise their liberation - and how they impact the white community as a result.

The disregard and ignorance by white theologians of black liberation theology in the 1960s, the 1980s was motivated by the notion that:

… it was not deemed worthy to be engaged as an academic discipline. Our struggle to make sense out of the fight for racial justice was dismissed as too narrow and divisive. (Cone 2002:10)

However, the moral obligation of white theologians remains to redress oppression at its very core, namely, white racist supremacy (Macedo 2001:xxix). Hence, Saayman (1990:17), a white South African theologian, urges white Afrikaners and all white people who want to make Africa their home to become white Africans without any illusions.

Critical pedagogy transformed Cone's Euro-American education. He explored and exposed the complexity and contradictions of the ruling class - and sought for an education of freedom that could foster a 'more just and less oppressive society'. His theology was deeply shaped by his context, race and class.

Cone's (2002) work provides a good theoretical backdrop for reviewing racism and the theology context in South Africa.

The black response to white racism: Courageous dialogue

In South Africa, Mosala (in Modise 2015:3,9) urges 'liberation theologians, as the "offspring of the struggle"' for liberation from apartheid in South Africa to continue the struggle by engaging new challenges. Despite our attainment of freedom in 1994, black liberation theologians failed to redress new challenges and caused the death of black liberation theologians. 'Since the death of apartheid, liberation theologians have [… gradually] generate [sic] post-apartheid black theology' (Modise 2015:3).5 However, we need to emphasise that we should not simply equate blackness to oppression without acknowledging the achievements of some black people in society. This would amount to a grave oversight of the empirical facts by Cone (Preston Williams in Boesak 1977:111-112). Neither should we disregard the notion that 'black people [all of us] cannot be racist' (Boesak 2009):

Since at least 1994 governmental power, in the many devastating ways it can be manifested, has been in the hands of black people. And that this power has been used for racist ends cannot be disputed. (p. 263)

Boesak's view is supported by Slater (2010), who voices a similar critique:

In the last twenty years, Black Theology has short circuited its liberative task in South Africa. Its proverbial voicelessness apropos the blatant oppression still active in South Africa and so apparent in the face of existing poverty, xenophobia, gender discrimination, homosexuality, ecological disasters, women and child trafficking, women and child abuse, cultural abuse as well as corrupt leadership and management is reprehensible. (p. 456)

In a similar courageous attitude displayed by Cone (1975):

[…] black theologians who have lived in the social context of racial oppression, we must not be afraid to ask the hard questions. … If blacks and whites have been reconciled [Eph 2:14-15 RSV], how come white racists are still oppressing blacks in South Africa … and elsewhere on the continent? (p. 227)

As Cone (1975) challenges us with the following questions:

How come white racists are still being elected to public office in America, thereby continuing their dehumanisation of black people in the name of God and country? How come white churches still support racial oppression either through silence or through their public defense of the order of injustice? How can we black people take seriously the unity in Christ Jesus when there is no unity in politics or religion? (p. 227)

Drawing on the work of Cone (1975; 2002), a new reflection/critique of Black Theology in South Africa is necessary. There has been an awareness of the need for new reflection as expressed by Mothlabi (in Brand 2010); for instance, she writes:

South African theology … seems to have lost its bearing and sense of direction, especially since the political change that took place in the country in 1994. Black theologians, in particular, have seemingly gone into recess … they have been mesmerised by the new developments that have taken place in the country since their political liberation and have not yet found a new way to relate to them. (p. 459)

Cone (2002) refers to 'white theology's amnesia about racism' as a direct consequence of:

… the failure of black theologians to mount a persistently radical race critique of Christian theology, one so incisive and enduring that no one could do theology without engaging white supremacy in the modern world. (p. 10)

Similarly, in the South African context, Kritzinger (1990:61) believes that white people can help to build a non-racial, democratic African state, liberated from the destructive structures of colonial racism. He cites Robert Sobukwe who wants to create space for white people to be 'Africans' (Kritzinger 1990:61).

According to Cone (2002:10), we black theologians have failed to develop an enduring radical race critique because of an uncritical identification with the dominant Christian and integrationist tradition in African-American (Eurocentric) history:6

When whites opened the door to receive a token number of us into the academy, church and society, the radical edge of our race critique was quickly dropped as we enjoyed our newfound privileges. (p. 10)

Similarly, within the South African context, critique has been levelled by black theologians against a passive acceptance of the status quo of the prevailing culture of white dominance. For example, Boesak (in Baloyi 2010:423) refers to a dependence on white resources/capital and the acceptance of an alien theology (Boesak in Baloyi 2010:427). Financial dependence on white capital has become a stumbling block - an evil that is suppressing the theological convictions of and avoidance of Black Theology by black theologians: 'In many cases, white control is still a reality, and this makes it difficult for black ministers to identify with the black church' (Boesak in Baloyi 2010:423).

From a feminist theology perspective, critique by the South African theologian Ackermann (1990) has been voiced. Ackermann specifically targeted the monopoly of black male theological discourse and challenged the male advocates of black theology, calling for a move from their narrow focus on race and liberation and to incorporate gender, class and sexuality critiques and the themes of survival and quality of life in our theological discourse (Cone 2002:10).

Cone's (2010) revolutionary critique of the dominance and oppression of the white world view as reflected in white theology serves as a format for courageous dialogue to address racial divides in epistemology and theology practice - to develop a congruent view in theory formation between knowledge and practice - so that black reality and experience is not ignored.

A more in-depth view on this courageous dialogue is given in the following section.

Racialised academic theology: Courageous dialogue

Cone raises concern about 'the absence of a truly radical race critique' (Cone 2002:11). Black and white South African theologians such as Maake Masango, Allan Boesak, Nico Smith, Beyers Naudé, Kritzinger, Saayman and Ackermann (Boesak 1977; Hofmeyr et al. 1990; Masango 2011) have, however, all demonstrated how they have developed and mobilised a radical race critique that helped to generate enough momentum towards a theology of liberation and freedom.

Cone (2002:11) maintains that Malcolm X influenced black theologians to engage white religion critically and to develop a 'hermeneutic of suspicion' regarding black Christianity:

How can African-Americans merge the 'double self' - the black and the Christian - 'into a better and truer self', especially since Africa is the object of ridicule in the modern world and Christianity is hardly distinguishable from European culture? (p. 11)

He furthermore holds that the applications of 'King and Malcolm X are crucial to slay the dragon of theological racism'. Martin and Malcolm represent the complete critique 'in the black attack on racism' (Cone 2002:11). An overemphasis of the one may lead to black domination and an emphasis on the second aspect may lead to an easy white request for reconciliation without justice and for the middle-class black people to grant it. Cone ultimately posits that '[t]here can be no racial healing without dialogue, without ending the white silence on racism. There can be no reconciliation without honest and frank conversation' (Cone 2002:11).

Because, the western world has persistently negated the reality of rich and poor, white and black, oppressors and the oppressed, oppression and liberation from oppression, Christian churches opted throughout history for a type of pseudo-innocence by hiding painful truths behind a façade of myths and paternalistic compassion (Boesak 1977:7). Masango (2011:2) raises concern about the violent strike actions in South Africa by grounding it within historic experiences of apartheid as painful memories that feature in contemporary black lives: 'People raised in a dysfunctional home will respond accordingly when faced with difficulties'. Privileged positions ought to be critiqued as not to offer help as a type of missionary paternalism, nor to limit possibilities to create structural empowerment (Macedo 2001:xxix). 'Racism is still with us in the academy, in the churches and in every segment of society because we refuse to deal with its past and present manifestations' (Cone 2002:10-11). Most white people refrain from talking about racism, and do not even consider the victims of racism coping with the attitudes of white supremacists. It is only when racism is declared overtly that we find some public recognition of its existence avidence is mounting that the very leitmotifs nd a possibility of racial healing. Silence and denial are at the core of racism (Cone 2002:12):

in the casual callousness of youth, those who went to school after 1994, 'Mandela's white children: … the 'Waterkloof Four'; the Reitz residence incident …; the Skierlik [township killings] … the first, most spontaneous reaction from certain sections of the white community was not outrage and condemnation, but denial and justification. There was shocked response - not at the horror of the killings, but at the possible judicial consequences. This reaction from the same community howling for the death penalty because of the crime and violence haunting South Africa. (Boesak 2009:264)

Cone's (2002:12) argument is based on Martin Luther King's proclamation that: '[a] time comes when silence is betrayal', and argues that 'that time has come for white theologians'. For Cone (2002:12), racism is the great contradiction of the Gospel and is strongly convinced that white theologians who do not oppose racism publicly and in their writings, are accountable and 'part of the problem and must be exposed as the enemy of justice' (Cone 2002:12).

Therefore, diplomatic silence and contradictions between contemporary generations in dealing with racism and hegemonic praxes stifle the redress of racism, especially by theologians (cf. Van Niekerk & Jones 2017:99-118).

Hence, Cone's call for mutual comprehension to collectively foster equity by transforming overt and more subtle racial discrimination and conflict. To this end, personal and collective engagement, honesty, endurance and persistence in dialogue about race require a commitment and accountability to stay engaged, experience discomfort, speak your truth, and expect and accept non-closure. A personal racial consciousness is of paramount importance to achieve any possible outcome in courageous dialogue.

A pedagogy of discomfort, critical reflection and courageous conversation illuminates aspects of both Cone's and Masango's life and work and informs a pedagogy of transformation towards total justice and freedom. Their theological and lived contributions to humanity embody Freire's (1998 in Dames 2016:59) notion of a humanisation pedagogy. Masango (2005:924) views justice from an African perspective 'for the common good of all human beings' by 'challenging the demonic powers that seek to destroy humanity'. Wolterstorff's (2004:22-23) observation in this regard is worth presenting and it intersects with the three pedagogies above. He calls for a comprehensive educational plan to incorporate humanity's wounds through God's vision of shalom grounded in justice. Not to teach abstract justice, but to practice justice (Wolterstorff 2004:24). Shalom, however, transcends justice - it fosters right relationships to God, human beings, nature and oneself (Wolterstorff 2004:23). Justice relates to Ubuntu and requires 'us to relate to each other as human beings' by restoring the values and ontology of humanity in village life and in transforming the unjust globalised economic structures that compromises human dignity (Masango 2014:4-50).

Towards a pedagogy of freedom and healing from racism

Building on Cone's (2002) lived narrative and critical theory grounded in a pedagogy of freedom and healing in search of a more just and less oppressive society (Zimmerman et al. 2011:20), we conclude by drawing on the work of Ackermann (1998), a white South African feminist theologian. Particularly, in the light of Cone's (1975; 2002) oversight to link liberation with reconciliation in his theology, as analysed by J. Deotis Roberts (in Boesak 1977:113), the author of Liberation and Reconciliation: A Black Theology.

Speaking from a historical South African context, Ackermann (1998) observes that:

[e]vidence is mounting that the very leitmotifs which inspired the resistance to apartheid are being marginalised: issues of morality, values and ethics in the shaping of civil society. Theological education is a case in point. (p. 77)

She rightly asks:

Does this imply that informed critical voices of religiously based communities are unwelcome in the new South Africa? If this is so what does it communicate about our leaders' visions for the future? What are the challenges to the church in this new situation? (p. 77)

For as such, it remains ironic how some tertiary institutions in South Africa continue to protect racism within institutionalised invincibility (cf. Tshwane 2017:13; Van Niekerk & Jones 2017:99-105).

Ackermann (1998:80-81) purports a hermeneutic of healing to regain our lost humanity as a core praxis for personal and social healing. Social healing and political healing are inseparable and crucial in South Africa, especially in light of political oppression and racialised social engineering.

According to Ackermann (1998:83), the victims of apartheid are in need of a healing praxis, which includes the healing for the white community. This is necessary because the division between white people as oppressors and black people as oppressed has led to despair and disillusionment and a distorted identity. Healing is therefore imperative at both ends of society. The 'white tribe' needs healing from their 'self-inflicted wounds of being oppressors towards a vision of a restored humanity' (Ackermann 1998:83). The healing of human rights violations and injustice through restoring of memory and humanity through the healing of denial and restoring to full humanity is crucial (Morton in Ackermann 1998:83; Graham & Poling 2000:165).

Ackermann (1998:91) recommends that healing must undergird accountability grounded in our different communities of accountability that shape our identities and our theologies through transmission of traditions, cultural norms, social mores, customs, rituals and myths.

The ideal of a pedagogy of healing and freedom is not unrealistic. White South African theologians demonstrated that the improbable is probable through the concrete embodiment of black theology and liberation theology in and through their personal, societal, public and professional lives (Ackermann 1990; Kritzinger 1990; Saayman 1990; Smit 1990). Kritzinger (1990:64-65), for example, urges white South Africans to learn an African language and to destroy their colonial arrogance and racism. Current lived narratives in South Africa, varying from students and ordinary members of society, attest to the fact that healing and freedom is possible even in the face of the harshest human ordeals in life. A recent book publication by Van Niekerk and Jones (2017) provides rich insights into real-life stories of young white and black South Africans who have experienced racism in violent, harsh and inexplicable complex life events. Some of these narratives demonstrate how young white and black persons developed a progressive racial consciousness that refuses to succumb to historical racial prejudice and racism that oppress and engender inequality (Van Niekerk & Jones 2017:73-98, 119-168). If reconstructed beyond, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa could help to generate footprints on all levels of society to re-engineer a non-racial, non-sexist society of equality (cf. Tutu in Van Niekerk & Jones 2017:187-189). It may not be too far-fetched to state that the new democratic South Africa may hold potential to mirror a pedagogy of healing and freedom grounded in a racial consciousness towards social healing, political healing and justice for all. This is probably through resocialisation on both our objective physical lifeworld and our subjective symbolic lifeworld to realise the transformation of the objective world of white people (Smit 1990:121-122). Note that Fanon (in Gibson 2011:8) proposed a 'subjective attitude in organised contradiction with reality'. Fanon's notion of subjectivity is not a product of pure will but refers to an organised self-consciousness - 'a practice emerging from the lived experience of the colonised in their struggles against colonial objectivity' (in Gibson 2011:8)7

It brings us to the following question: how should we apply the pedagogy of Masango to enhance liberation and healing from racism, beyond cheap grace and reconciliation?8 To this end, Masango observes that:

The African concept of ubuntu [humanity] can be applied also to the way in which African people groom their children. Tshepo grew up without the hang-ups that older people have on account of apartheid. Growing up, she internalised positive aspects, such as having been taught to love oneself; in other words, it was a process of positive growth which became part of a positive life. This story illustrates what individuals can bring into relationships, be it at the university, in the church or in industry. (Masango 2011:2; cf. Van Niekerk & Jones 2017:163-172, 181-186)

Masango's (2011:2) narrative resonates with Cone's (1975:132) lived narrative in concurrence with Jesus' embodied and liberating presence to redeem and heal all humanity without an imposed and distorted identity.

Conclusion

If the reality of Masango (2011:2) and Cone (1975:132) does not convince racists of the daily lived realities of black people and 'the impending judgement of Jesus', then it must be declared that we may be heading to a dead end. Yet, the spirits of Cone and Tshepo - the Masango family - urge humanity not to succumb to white supremacists and racists.

Similarly, Cone (2002) challenges both members of the dominant and marginalised cultures through critical theory to analyse and act against oppressive racial and social injustices. His revolutionary critique of the dominance and oppression of the white world view as reflected in white theology serves as a format for courageous dialogue to address racial divides in epistemology and theology practice so that black reality and experience is not ignored. In response, we can concur that healing must undergird accountability by different racial communities that shape our identities and theologies (Ackermann 1998:91). It is for this reason that a dangerous pedagogy of discomfort, courageous dialogue and critical reflection and action is proposed to break the shackles of racism and to forge a new future of freedom and healing.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that he or she has no financial or personal relationships which may have inappropriately influenced him or her in writing this article.

References

Ackermann, D., 1990, 'The Black Sash: A model for white women's resistance', in M. Hofmeyr, K. Kritzinger & W. Saayman (eds.), Wit Afrikane?: 'n gesprek met Nico Smit, pp. 21-32, Taurus, Bramley. [ Links ]

Ackermann, D., 1998, 'A voice was heard in Ramah: A feminist theology of praxis for healing in South Africa', in D.M. Ackermann & R. Bons-Storm (eds.), Liberating faith practices: Feminist practical theologies in context, pp. 75-102, Peeters, Leuven. [ Links ]

Balcomb, T., 1990, 'Third way theologies in the contemporary South African situation - Towards a definition, critique and comparison', in M. Hofmeyr, K. Kritzinger & W. Saayman (eds.), Wit Afrikane?: 'n gesprek met Nico Smit, pp. 33-46, Taurus, Bramley. [ Links ]

Baloyi, M.E., 2010, 'The sustentasie problem in the reformed churches of South Africa: Unmasking the dilemma facing black theologians', Scriptura 105, 421-433. https://doi.org/10.7833/105-0-154 [ Links ]

Batts, V., 2013, 'Modern racism: New melody for the same old tunes (extracts from Shifting paradigms)', presented by R. Williams & M. Steyn (eds.) as 'Social context and management workshop resources', of Embrace in association with the Wits Centre for Diversity Studies Report for the Department of Philosophy, Practical and Systematic Theology: Difficult conversations: 'race', racism and transformation, Unisa, Pretoria, February 12-13, 2013. [ Links ]

Boesak, A., 2009, Running with horses: Reflections of an accidental politician, Joho, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Boesak, A.A., 1977, Afscheid van de onschuld: Een social-ethischestudie over zwartetheologie en zwartemacht, Kok, Kampen. [ Links ]

Boler, M. & Zembylas, M., 2003, 'Discomforting truths: The emotional terrain of understanding difference', in P. Trifonas (ed.), Pedagogies of difference: Rethinking education for social change, pp. 110-136, Routledge Falmer, New York. [ Links ]

Botman, H.R., 2000, 'Discipleship and practical theology: The case study of South Africa', International Journal of Practical Theology 4, 201-212. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijpt.2000.4.2.201 [ Links ]

Brand, G., 2010, 'Criteria, language and the revitalisation of black theology', Scriptura 105, 459-469. https://doi.org/10.7833/105-0-165 [ Links ]

Brown Douglas, K., Jones, S. & Warnock, R. 2018, Reflect on the life and legacy of Dr. James Cone, KeneticsLive.com, viewed 20 September 2018, from https://mailchi.mp/75e34fa91af7/drs-kelly-brown-douglas-serene-jones-and-raphael-warnock-reflect-on-the-life-legacy-of-dr-james-cone?e=18f250e8d4 [ Links ]

Chimhanda, F.H., 2010, 'Black theology of South Africa and the liberation paradigm', Scriptura 105, 434-445. https://doi.org/10.7833/105-0-163 [ Links ]

Cone, J., 2002, 'Looking back, going forward', in D.C. Marks (ed.), Shaping a theological mind: Theological context and methodology, pp. 1-14, Ashgate, Aldershot, England. [ Links ]

Cone, J.H., 1975, God of the oppressed, 4th edn., The Seabury Press, New York. [ Links ]

Dames, G.E., 2014, A contextual transformational practical theology in South Africa, AcadSA Publishing CC. [ Links ]

Dames, G.E., 2016, Towards a contextual transformational practical theology for leadership education in South Africa, LitVerlag, Zürich. [ Links ]

Dames, G.E., 2018, 'Perpetual depiction of the creative black image of God by white supremacists', Photo recording, February 19, 2018, Die Meerkatgat Padstal, Colesburg. [ Links ]

Durrheim, K., Mtose, X. & Brown, L. (eds.), 2011, Race trouble: Race, identity and inequality in post-apartheid South Africa, University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, Pietermaritzburg. [ Links ]

Freire, P., 2001, Pedagogy of freedom: Ethics, democracy, and civic courage, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Lanham. [ Links ]

Gibson, N.C., 2011, Fanonian practices in South Africa: From Steve Biko to Abahlali baseMjondolo, UKZN Press, Palgrave Macmillan, Pietermaritzburg. [ Links ]

Graham, E. & Poling, J., 2000, 'Some expressive dimensions of a liberation practical theology: Art forms as resistance to evil', International Journal of Practical Theology 4, 163-183. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijpt.2000.4.2.163 [ Links ]

Gutiérrez, G., 2014, A theology of liberation, 15th edn., Orbis Books, Maryknoll, NY. [ Links ]

Hansen, L. (ed.), 2007, Christian in public: Aims, methodologies and issues in Public Theology, vol. 3, Sun Press, The Beyers Naudé Centre Series on Public Theology, Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Hofmeyr, M., Kritzinger, K. & Saayman, W. (eds.), 1990, Wit Afrikane?: 'n gesprek met Nico Smit, Taurus, Bramley. [ Links ]

Kgomosotho, G. 'Go to the root to eradicate racism: Jail and laws against hate crimes and speech alone cannot rid South Africa of this prejudice', Mail & Guardian, 5-11 October 2018, p. 33. [ Links ]

Kritzinger, K., 1990, 'Teologie vir wit bevryding (Theology for white liberation)', in M. Hofmeyr, K. Kritzinger & W. Saayman (eds.), Wit Afrikane?: 'n gesprek met Nico Smit, pp. 54-66. Taurus, Bramley. [ Links ]

Macedo, D., 2001, 'Foreword', in P. Freire (ed.), Pedagogy of freedom. Ethics, democracy, and civic courage, pp. xi-xxxii, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Lanham, MD. [ Links ]

Makinana, A., 2018, Ramaphosa: 'From Bonteheuwel to Westbury‚ let's end the violence of despair', Sowetan Live, accessed 9 October 2018 from https://www.sowetanlive.co.za/news/south-africa/2018-10-09-ramaphosa-from-bonteheuwel-to-westbury-lets-end-the-violence-of-despair/ [ Links ]

Masango, M., 2005, 'The African concept of caring', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 61(3), 915-925. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v61i3.465 [ Links ]

Masango, M., 2011, 'Mentorship: A process of nurturing others', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 67(1), 1-5, Art. #937, https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v67i1.937 [ Links ]

Masango, M.J., 2014, 'An economic system that crushes the poor', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 70(1), 1-5, Art. #2737, https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v70i1.2737 [ Links ]

Modise, L.J., 2015, 'Liberation theology as doing theology in post-apartheid South Africa: Theoretical and practical perspectives', in F.H. Chimhanda, V.M.S. Molobi & I.D. Mothoagae (eds.), African theological reflections: Critical voices on liberation, leadership, gender and eco-justice, pp. 2-17, Unisa: Research Institute for Theology and Religion, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Motsi, R.G. & Masango, M.J., 2012, 'Redefining trauma in an African context: A challenge to pastoral care', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 68(1), 1-8, Art. #955, https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v68i1.955 [ Links ]

Nipkow, K.E., 2003, God, human nature and education for peace: New approaches to moral and religious maturity, Ashgate, Birlington. [ Links ]

Njilo, N., 2018, 'Coloured people are 'tired of what is going on'‚ say Eldorado Park residents', Sowetan Live accessed 5 October 2018, from https://www.sowetanlive.co.za/news/south-africa/2018-10-05-coloured-people-are-tired-of-what-is-going-on-say-eldorado-park-residents/ [ Links ]

Pijoos, I., 2018, 'Vicki Momberg sentenced to an effective 2 years in prison for racist rant', News24: Breaking News First, 16 April, viewed 20 April 2018, from https://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/vicki-momberg-sentenced-to-an-effective-2-years-in-prison-for-racist-rant-20180328 [ Links ]

Pui-lan, K., 2005, Postcolonial imagination & feminist theology, Westminster John Knox Press, Louisville, KY. [ Links ]

Saayman, W., 1990, 'Muprofita vadurya', in M. Hofmeyr, K. Kritzinger & W. Saayman (eds.), Wit Afrikane?: 'n gesprek met Nico Smit, pp. 15-20, Taurus, Bramley. [ Links ]

Segalo, P. & Mothoagae, I.D., 2015, 'Gender: Equity and ethnic mobilisation: Assets for democracy and social cohesion in South Africa?', in F.H. Chimhanda, V.M.S. Molobi & I.D. Mothoagae (eds.), African theological reflections: Critical voices on liberation, leadership, gender and eco-justice, pp. 231-246, UNISA: Research Institute for Theology and Religion, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Singleton, G.E. & Curtis, L., 2006, Courageous conversations about race: A field guide for achieving equity in schools, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA. [ Links ]

Slater, J., 2010, 'Black theology: Funeral arrangements or a quantum leap towards resuscitation', Scriptura 105, 446-458. https://doi.org/10.7833/105-0-164 [ Links ]

Smit, D., 1990, 'Prof Nico se storie … oor narratiewe teologie, herinneringe en hoop', in M. Hofmeyr, K. Kritzinger & W. Saayman (eds.), Wit Afrikane?: 'n gesprek met Nico Smit, pp. 110-127, Taurus, Bramley. [ Links ]

Steyn, T.H. & Masango, M.J., 2012, 'Generating hope in pastoral care through relationships', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 68(1), 1-7, Art. #957, https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v68i1.957 [ Links ]

Tfwala, N. & Masango, M., 2016, 'Community transformation through the Pentecostal churches', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 72(3), 1-9, a3749. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v72i3.3749 [ Links ]

Tshaka, R.S. & Mogashoa, M.H., 2010, 'Black theology in South African context', Scriptura 105, 419-635. [ Links ]

Tshwane, T., 2017, 'Wits med school hit by racism claim', Mail & Guardian, December 1 to 7, 2017, p. 13. [ Links ]

Van Niekerk, P. & Jones, C., 2017, Saam in Suid-Afrika [Together in South-Africa], [ Links ] LuxVerbi, Cape Town.

Wolterstorff, N., 2004, Educating for shalom: Essays on Christian higher education, C.W. Joldersma & G.G. Stronks (eds.), Eerdmands, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Zimmerman, L.W., McQueen, T. & Gwendolyn, G. (eds.), 2011, 'Connections, interconnections, and disconnections: The impact of race, class and gender in the university classroom', Journal of Theory Construction and Testing 11(1), 16‒21. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Gordon Dames

damesge@unisa.ac.za

Received: 30 Apr. 2018

Accepted: 21 Sept. 2018

Published: 18 Feb. 2019

Note: The views expressed in this article are my own and not an official position of my institution or any funder.

1 . 'Hegemony refers to the maintenance of domination not by the sheer exercise of force but primarily through consensual social practices, social forms, and social structures produced in specific sites such as the church, the state, the school, the mass media, the political system, and the family' (McLaren 1998:182 in Boler & Zembylas 2003:111).

2 . 'I have learnt from Black Theology that God identifies Himself with the poor and the oppressed and afflicting the oppressor in support of the oppressed (Cone 1975:63). I realise that as long as a Reformed black minister is not liberated (economically), his or her Black Theology will not always reflect the feelings of the black people whom he or she serves. God must become the voice of the voiceless as Cone mentioned, and theology must consider the circumstances of the people it addresses' (Baloyi 2010:422-423).

3 . 'The picture about the marginalisation of black people is exacerbated by the fact that there is an emergent black elite making up black leadership and that is sometimes accused of corruption, nepotism, poor service delivery and lack of expertise' (Chimhanda 2010:437).

4 . 'The majority of whites in this country [South Africa] look to Europe for their cultural sustenance and for the perpetuation of their Western-Christian norms and values - firmly embedded in white supremacy. That is their mistake' (Mattera 1988 in Kritzinger 1990:63).

5 . Compare Black Theology in South African Context, edited by Tshaka and Mogashoa (2010).

6 . It is always the grassroots intellectuals of an exploited group who must take the lead in exposing the hidden crimes of criminals. Although black theologians' initial attack on white religion shocked white theologians, we did not shake the racist foundation of modern white theology. But white theologians in the seminaries, university departments of religion and divinity schools, and professional societies refused to acknowledge racism as a theological problem and continued their business as usual, as if the lived experience of blacks was theologically irrelevant (Cone 2002:10).

7 . In The Wretched of the Earth, Fanon notably adds that the starving 'natives' don't need to discover the truth but are the truth, since they experience the truth of the colonial system - its violence and dehumanisation - and understand the truth of the anti-colonial revolt as one of bread and dignity. Yet this identity of truth and experience has not yet fully moved to self-acting subjectivity. Rather than simply a for-itself 'subject position', subjectivity here is understood as an actional and conscious subject. … how this subject position can become a self-determining, actional subjectivity that can absorb and change not only itself, but also the objective material world into a free, inclusive, democratic space. (Fanon in Gibson 2011:8-9)

8 . Tutu explains that real healing results from having dealt with the real situation (1999:218). He makes important recommendations undergirding the reconciliation process: that reconciliation must not be cheap (spurious); for the victims of war atrocities, the main thrust is 'anamnesis' (recollection) of the painful memories; that perpetrators of oppression must be held to account for their deeds and ask for forgiveness in return for pardon; and that the process of narrating the harrowing experiences of oppression from apartheid to a supportive and non-judgmental audience is cathartic (Tutu 1999:279). Recognising that reconciliation, like liberation theology is an on-going dynamic process and also the limitations of the TRC (eg. not all cases of atrocities were covered, and, having opened wounds, one must see the patient through the whole healing process) the challenge for Black Theology in post-apartheid South Africa today is to go behind and beyond the TRC (Chimhanda 2010:436).