Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

HTS Theological Studies

versión On-line ISSN 2072-8050

versión impresa ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.75 no.3 Pretoria 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v75i3.5656

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

A realistic reading of the parable of the Lost Coin in Q: Gaining or losing even more?

Ernest van Eck

Department of New Testament and Related Literature, Faculty of Theology and Religion, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

This article aims to present a realistic reading of the parable of the Lost Coin in Q. A realistic reading of the parable focuses on the social realia invoked by the parables, that is, the social realities and practices (cultural scripts) embedded by any given parable. As will be indicated, available documented papyri can be used to identify the possible social realia invoked by the parables, and this can help the modern reader to identify what is 'normal' or 'abnormal' in a parable being interpreted. This, in turn, can help the modern reader to come to grips with the probable intended meaning of the parable. In a realistic reading of the Lost Coin, it is argued that two things are important: the price and daily consumption of oil, and the Lost Coin being one of the gendered doublets in Q. Apart from proposing a possible meaning of the Lost Coin, it is also indicated that a realistic reading explains why the seeking of the woman is described as being ἐπιμελῶς [diligent].

Keywords: Lost Coin; parables; historical Jesus; Q; cost and usage of lamp oil.

Introduction

Dodd (961), in his reading of the parables, treated the parables as didactic stories, explored their eschatological dimensions and focused on the original intention of the parables in their historical settings. Dodd insisted that the parables should be heard by the modern interpreter as they were heard by Jesus' original 1st-century Jewish Palestinian audience. This approach culminated in his now well-known definition of a parable as a 'metaphor or simile drawn from nature or common life, arresting the listener by its vividness or strangeness' (Dodd 1961:5; emphasis added).1

Dodd's definition of a parable informs a realistic reading of the parables in two ways. Firstly, a realistic reading of the parables takes as point of departure that the parables are stories drawn from nature or common life, that is, stories to be read against the backdrop of the social realia (cultural scripts of sociocultural features) invoked by a given parable. From this perspective, the parables of Jesus are stories about shepherds attending to flocks of sheep and not stories about Jesus looking for lost sinners (Lk 15:4-6), day labourers being hired to work in a vineyard and not God who invites gentiles to become part of the kingdom (Mt 20:1-15) and servants whose debts are released, and not God who forgives abundantly (Mt 18:23-33). As suggested by Kloppenborg (2014a:490), we have to consider that possibility that in the parables, 'a vineyard or a shepherd … is just a vineyard or a shepherd'.

Applied to the parable of the Lost Coin, the woman searching for her lost coin is not a metaphor for God, as have been argued, for example, by Hultgren (2000:64), Boucher (1981:98) or Blomberg (2012:214). The woman also does not reveal 'vital information about the character of God' (Snodgrass 2008:111), or shows metaphorically what 'Jesus is doing', that is, 'finding/saving the lost ones' (Crossan 2012:38, 40). From the point of view of a realistic reading, the woman is just a (peasant) woman, not looking for a sinner or the lost, but a coin with the value of 1 drachma.

As a realistic reading of the parables focusses on the social realia invoked by each parable, the focus of the reading is the sociocultural features drawn from nature or common life that forms the backdrop of a specific parable. A realistic reading of the Lost Coin therefore asks the following questions: was the woman, owning 10 drachmas, poor or rich? Does she have a husband or not? What did her house look like? Did she own the house? Why was it necessary to light a lamp to look for the coin? Who were her neighbours? What was the value of a drachma? More important even, what was the buying power of 1 drachma? Was it normal to light up a lamp to look for something like a coin? What was the woman's status? Hultgren (2000:66), for example, poses some of these questions,2 but argues that 'all these questions are actually beside the point of a good story'. Blomberg (2012) shares this sentiment:

Other details in these two parables (the Lost Sheep and Lost Coin) - the wilderness and the shepherd's home, or the lamp with what the women searches her house - add nothing to the meaning of the narratives but simply act as the logical 'stage props' for the action of the main characters. (p. 216; emphasis added)

For a realistic reading of the parables, to the contrary, any piece of detail in a parable that in some way or other relates to its sociocultural background is deemed as important.

The second way in which Dodd's definition of a parable informs a realistic reading of the parables is the vividness or strangeness of details (social realia) in a parable that creates meaning for the original hearers' listening to the parable. The first audience of Jesus' parables, as Kloppenborg (2014a:2) has argued, most probably had native knowledge of the social realia referred to in the parables. For them, the mention of a peasant home most probably would have invoked a very vivid picture, as well as celebrations with neighbours. Lighting up a lamp to look for a lost coin, however, with the mere value of 1 drachma, would have seen as normal or strange. And if it was considered strange, or abnormal, was that the 'surprise' in the parable that, for them, carried its meaning? Moreover, as Levine (2014:1) has argued that what seems odd (strange or abnormal) to the modern reader might have been perfectly normal to the first hearers of a parable, and what may seem normal to the modern reader might have been perceived as odd or surprising to the first hearers of a parable.

To distinguish between 'normal' and 'abnormal' social practices and realities in any given parable, the knowledge of cultural scripts and social realia embedded in the parable is indispensable to understand what message the parable intends to convey. And for this, as will be argued and discussed below, information provided by Roman-Egypt-documented papyri is indispensable.

To get to the social context of the Lost Coin, which is vividly expressed by its content (Dodd), sociocultural information available in documented papyri can be used to identify the possible social realities and practices (cultural scripts) invoked by the parable. The knowledge of these social realia will then help the modern reader to identify what is vivid ('normal') in the parable and what most probably is strange ('abnormal'). And what is strange most probably will in some way or the other lead the modern reader to the intended meaning of the parable.

The sociocultural background of the Lost Coin

When details in the parable of the Lost Coin (e.g. the lamp or the house in which the coin got lost) are considered as beside the point of a good story (Hultgren 2000:66), or mere logical stage props to facilitate the actions of the characters in the parable (Blomberg 2012:216), the social realia invoked by the parable is obviously not deemed as an important contributor to a possible meaning of the parable in its originating setting. Moreover, as most available interpretations of the parable read it in its literary context, taking Luke's allegorical application of a Jesus parable as cue, it is not surprising that only scant references to the sociocultural background of the parable can be found in available interpretations.

When these interpretations refer to the social realia invoked by the parable, the focus is on the status of the woman, the house, why the woman possesses 10 drachmae and the value of a drachma. The woman is either described as poor (Boucher 1981:98; Hultgren 2000:66; Merz 2007:612) or well-off (Levine 2014:42; Snodgrass 2008:113),3 and married or unmarried (Schottroff 2006:154). The house in which the coin got lost is described as small (Merz 2007:612; Schottroff 2006:153; Snodgrass 2008:113), with no windows for natural lighting (Hultgren 2000:67; Jeremias 1972:135; Kistemaker 1980:175; Schottroff 2006:154), or with small windows with a low door or opening letting in limited natural light (Jeremias 1972:135; Kistemaker 1980:175; Snodgrass 2008:114). The women thus had to lit a lamp to look for the coin, most probably lodged in one of the many cracks of the floor (Snodgrass 2008:114), even if the search took place during daylight (Merz 2007:612).

Why was the woman in possession of 10 drachmae? Some argue that the lost coin was part of the woman's headdress bedecked with coins as part of her dowry (Bishop 1955:191; Jeremias 1972:134; Kistemaker 1980:174; Morgan 1953:189; Scott 1989:311-312), while others see this possibility, based on evidence from m. Kelim 12.7, as ill-founded (see, e.g., Snodgrass 2008:114). Schottroff (2006:154), at her turn, believes that the woman worked for the money. Regarding the value of a drachma, there is more or less unanimity among interpreters of the parable: a drachma was the equivalent of the denarius,4 more or less equalling a peasant's subsistence wage for a day's work (see, inter alia, Hultgren 2000:66; Scott 1989:311; Snodgrass 2008:113), and, according to Schottroff (2006:154), enough money to buy food for 2 days.

The sociocultural background of the Lost Coin and the use of papyri

In the recent past, some parable scholars, who are interested in reading the parables in their original setting, started using papyri from early Roman Egypt as a source that gives evidence to the social realia and social practices that are presupposed by the parables (see, e.g., Bazzana 2011:511-525, 2014:1-8; Kloppenborg 2006, 2014a, 2014b:287-306; Van Eck 2016, 2017:163-184; Van Eck & Kloppenborg 2015:1-15; Van Eck & Van Niekerk 2017:163-184, 2018:1-11). These papyri - with due allowance made for differences between Roman-Egyptian and Roman-Palestinian sociocultural practices - provide ancient comparanda on the practices and social realities which the parables of Jesus presuppose (Kloppenborg 2014b:289; see also Vearncombe 2014:314). These papyri also usually are our most plentiful, and sometimes only, resource to identify the social realia and social practices embedded in any given parable (Kloppenborg 2014a:2). Using these papyri can help the interpreter of a parable 'to get clear on the most basic meanings of the images in question (invoked by the parable) before moving to abstract, symbolic or allegorical meanings' (Kloppenborg 2014a:490).

Using these papyri therefore can help answer the question if the woman in the parable indeed functions as a symbol or metaphor for God, or simply should be seen as a peasant woman looking for a lost coin.5 In brief, using papyri from early Roman Egypt as a source that gives evidence to the social realia and social practices that are presupposed by the parables facilitates a realistic reading of the parables.

Erin Vearncombe, in a 2014 article, has performed an extensive realistic reading of the parable of the Lost Coin (Q 15:8-9) using early Roman-Egyptian papyri (see Vearncombe 2014:307-337). Starting with the question why the woman in the parable was in possession of 10 coins, she indicates that a wealth of papyri attests to the fact that women owned, controlled and disposed property such as 'houses, parts of houses, workshops, sums of money, and objects such as furniture, slaves, animals, equipment and tools, clothing, jewellery, produce and provisions' (Vearncombe 2014:314; see, e.g., P. Bad. 2.35; P. Mert. 2.83; P. Brem. 63; P. Tebt. 2.389; P. Oxy. 1.114, 6.932; P. Berl. Dem. 3142). Although the parable is not explicit about whether the woman lives alone or not, some papyri indicate that some women lived alone, and that women could experience stress in the absence of a male family member (P. Bad. 4.48; P. Flor. 3.332). Papyrological evidence thus confirms that it was custom for women to possess sums of money, own dwellings and live alone (Vearncombe 2014:314-317).

Regarding the relative value of 10 coins (10 drachmae), she agrees with most scholars that the value of 1 drachma is more or less equivalent to the Roman denarius. From available papyri, it seems that wages for agricultural tasks were in the range of 4 obols per day (1 drachma = 6 obols), and even it was 1 drachma, it was not a 'generous amount, meeting bare subsistence needs only' (Vearncombe 2014:319).6 Working with this equation, she estimates that the 10 drachmae of the woman was the equivalent of perhaps 2 weeks of work. As such, the 'characterization of the woman in the parable as poor would be very appropriate' (Vearncombe 2014:320).7

Turning to household maintenance, evidence from papyri indicates that it was a regular part of the upkeep of a dwelling (e.g. P. Mil. Vogl. 2.77). References to lamps are scant in available papyri, but one papyrus (P. Corn 1 = SB 3.6796) gives a very detailed record of lamp oil assigned to the entourage of a certain Apollonius, down to an eight of a kotyle, with 1 kotyle (= 1/12 of a chous) equalling approximately 0.27 L. Importantly, this record indicates 'that lamp oil was monitored precisely, with amounts being carefully measured' (Vearncombe 2014:321). She continues (Vearncombe 2014):

Her lighting of the lamp in order to search for the coin is significant, however; lamp oil seems to have been carefully managed, and in a situation where a single drachma was worth a search, in a subsistence-level circumstance, the lighting of a lamp was not a negligible or insignificant action. (p. 321)

Vearncombe (2014:321-322) next discusses the coins as property of the woman, indicating that evidence from the papyri describing the content of dowries refutes the possibility that the lost coin was part of a headdress that formed a part of the woman's dowry, as was argued before (see, e.g., P. Mich. 2.121). It also seems that the action of searching and finding was a quite common practice, attested to in several papyri (see, e.g., P. Mich. 1.26, 1.74, 8.503; P. Tebt. 3.1, P. Corn. 48; P. Oxy. 14.1680). Evidence from available papyri finally indicates that relationships between neighbours were not always amicable and without problems. Neighbours at times may have been the subject to some surveillance, and at times suspected of theft (see SB 12.11125, 16.12326; P. Oxy. 10.1272). As such, the celebration after the coin has been found, which was a normal event, could also have served to eliminate the possibility of theft (Vearncombe 2014:323).

Price of oil and daily usage

In her excellent study of the possible sociocultural background of the Lost Coin, using early Roman-Egyptian papyri, Vearncombe (2014) makes two remarks that are important for a realistic reading of the Lost Coin. Firstly, she indicated that it seems that the use of lamp oil was monitored precisely, with amounts being carefully measured. Secondly, she commented that, considering that the woman lived at a subsistence level, her lighting of the lamp to search for a coin with a value of 1 drachma is significant. Why the meticulous measuring of lamp oil used, and why is the woman's lighting of a lamp significant? To answer these questions, it is important to indicate, as far as possible, what the price of lamp oil was and the quantities used say by an individual or household on a daily basis. With this information available, one can then calculate how much it costs to lit a lamp for light in a house, or to look for a lost coin. As will be discussed below, available papyri contain a vast amount of information that can help with these kinds of calculations.

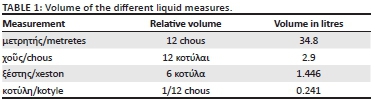

Firstly, however, it is necessary to indicate in which units liquid volume was measured. This is needed not only to calculate the cost of lamp oil per volume used, but also as a guide for liquid volumes used in available papyri. While the primary volume unit used to quantify amounts of dry goods was the artaba [ἀρτάβη], the volume of liquids, such as wine and oil, was quantified in metretes [μετρητής]. A metretes was usually equivalent in volume to a jar known as a keramion [κεράμιον]. A metretes was divided into the chous [χοῦς], and equalled 12 chous. The chous was further subdivided into 12 kotylai [κοτύλαι; sing. κοτύλη] (Hayden 2018:279-280; Maresch 1996:187; Pestman 1994:49; Sandy 1989:9-10).8 According to Aristophanes, a kotyle equalled half a ξέστης (ἡμίξεστον), with a ξέστης equalling the Roman sextarius (measured as half a chous).9 If a chous had a volume of 2.9 L (see Hayden 2018:279; Pestman 1994:48), the volume of the different liquid measures can be indicated as shown in Table 1.10

What was the price of oil used for lighting? In determining the price of oil used for lighting, one must take into consideration that only oil produced from sesame and castor seeds was used for cooking, lighting and, potentially, medicine (Hayden 2018:423). In available papyri, oil produced from theses seeds is distinguished with the terms σησάμινος [sesame oil] and κίκιον [castor oil] (see Grenfell & Mahaffy 1896:132; Hayden 2018:425; Sandy 1989:18-19). Also, where 'ἔλαιον is found in the papyri of this period, meaning one kind of oil, the presumption is that sesame oil is meant' (Sandy 1989:19). A search in available documented papyri for σησάμινος, κίκιον and ἔλαιον (and their derivatives), where price per volume is also mentioned, yielded the following information that can be used to get an indication of the price for lamp oil.

In available documented papyri, we have two occurrences of σησάμινος (see Hayden 2018:430). In P. Rev. 40.1211 (Arsinoitesnome, 259 BCE), the price for sesame oil (σησάμινον) is indicated as 12 drachmae per metretes (i.e. 8.275 obols per litre),12 and in P. Rev. 40.14 and15, it is indicated as 2 obols per kotyle (8.298 obols per litre). References to castor oil [κίκιον] occur more often in documented papyri, and in most cases, the price per litre is indicated as more or less 48 drachmae per litre. This, for example, is the case in P. Rev. 40.15-16 (Arsinoites, 259 BCE) and in P. Col. Zen I.21.413 (= P. Col. 3.21; Memphis, 257 BCE), a letter from Nikon, an agent of Apollonios, to Panakestor, in which he complains about the loss of castor oil given to some donkey drivers. In P. Rev. 53.15, the price of castor oil [κίκιον] is indicated as 2 obols per kotyle, the same as the price for sesame oil [σησάμινον] in P. Rev. 40.15. In some cases, a lower price is indicated. In P. Rev. 40.13, the price for 1 metretes of castor oil is 30 drachmae (i.e. 5.172 obols per litre), and in P. Rev. 53.20, it is indicated as 19 drachmae and 2 obols per metretes (3.333 obols per litre). In PSI IV 531.8, the price of 1 χαλμαιαν τοῦἐλαίου is calculated at 1 drachma and 4.5 obols, but as it is not clear what a χαλμαιαν measures, a price per litre cannot be calculated. References to castor oil are also found in SB XXIV 16067 and UPZ II 158; however, as no unit of measurement is given, it cannot also be used to calculate a price per litre.

Turning to the occurrences of ἔλαιον, we have four references in the Oxyrhynchus-papyri. In P.Oxy. 4.736.15 (Oxyrhynchus, 1 CE),14 the price of oil is indicated as 1 chous for 4 drachmae and 4 obols, thus a price of 8.965 obols per litre. In P.Oxy4.739.11 and 16 (1 CE), the price for a chousis, respectively, is set at 4 drachmae and 2 obols ['ἐλαίου χοῦς (δραχμαὶ) δ (διώβολον)'; i.e. 9.655 obols per litre] and 4 drachmae and 3 obols ['ἐλα[ίου] (δραχμαὶ) δ (τριώβολον)'; i.e. 10 obols per litre]. P.Oxy. 4.819.15 (1 CE) sets the price of 1 chous at 5 drachmae, thus a price of 10.344 obols per litre. In P.Fay101 v.1.9 (Euhemeria from the Arsinoitesnome; 18 BCE), the price for 1 choenix of oil is given as 5 drachmae.15 The choenix is a dry measure, but equals more or less 0.9463 L of liquid volume. If this volume is taken as equivalent to the choenix, the price will be 6.211 obols per litre. P. Petr. 3.137 (3rd century BCE; Arsinoitesnome) finally has six references to the price of oil as 4 obols (ἔλαιον τέταρτον ὀβολοῦ; see P. Petr. 3 137.1.4, 9, 16, 21; 2.10, 16). Here, we are set with a challenge, as the papyrus does not give the unit of measure; although the price is referenced to several times, these references do not help in determining the price of oil per litre.

From the figures above, it seems that from 279 BCE up to 1 CE, the price of oil was somewhere between 3.3 and 10.33 obols per litre, with 8.2 obols per litre (1 drachma and 2 obols) more or less the mean figure.16 Taking into consideration that prices over time normally increase, a price of more or less 10 obols per litre in the 1st century would be a good estimation (see P. Oxy 4.739.11, 16; 4.819.15).

Some texts differ quite drastically from this number. In P. Tebt 3.885 and 3.891, for example, prices of 2880, 4032, 7200 and even 8640 drachmae per metretes are mentioned. According to Hayden (2018:433), these higher prices maybe because of dramatic price increases that at times did occur, and also may be related to the status of the buyer or the relationship between the buyer and the seller. Josephus (Life 1:75-76), for example, relates the incident during which John of Gischala heard that 80 sextarius (40 chous) of oil was sold in Caesarea for 4 drachmae. He then bought all the oil and resold it at a price of 1 drachma for a chous, thus making a huge profit. He also, according to Josephus (J. W. 2:590-593), pretended that Jews staying in Syria were only allowed to use oil produced in their homeland and therefore got permission to send oil to some Jews living in Syria. By buying oil in bulk, at times as much as 4 amphorae, at a low price and selling it at a much higher price, he again made a noteworthy profit. Trading in oil seems to have been a normal economic activity, as can be detected from several papyri that have toll receipts for oil as content,17 as well as several ostraca that contain custom passes for the export of wine and oil.18 It also seems that as the oil trade made such huge profits, at times the price was set by ordinance.19 This, however, did not stop sellers from overcharging buyers.20

Available ostraca and papyri also indicate that oil for cooking and lighting was a necessary commodity. Several papyri, for example, contain delivery orders for oil,21 and in contracts with (professional) nurses to look after the sick or in contracts to rear children - almost all these contracts include the provision of oil for cooking and lighting.22 Being a necessity, sometimes, oil-makers were not allowed to move from nome to nome because such movement could have led to a scarcity of oil in certain nomes (see P. Rev. 44-46, in Hayden 2018:97).

Turning to oil use patterns, documented papyri contain some information that can help in determining the amount of oil most probably used per individual per day. Firstly, it seems that it was not uncommon practice for wills, in the form of a contract, to include a stipulation on the provision of oil. In P. Mich. 5.321 (Tebtynis, in the Arsinoitesnome, 42 AD), Orseus, son of Nestnephis, divides his property among his four children. Although the legal division is to be made after his death, the heir immediately takes hold of his inheritance at once, as is clear from the fact that his eldest son, Nestnephis, agrees to pay for his father 12 drachmae a year for oil. In P. Mich.5.322a (Tebtynis, in the Arsinoitesnome, 46 CE), also a will in the form of a contract, the sons, daughters and grandsons of Psyphis and Tetosiris are required to provide their parents with wheat, money for clothing and other expenses, as well as 6 kotyle of oil per month, that is, an amount of 2 drachmae per month.23P. Mich.5.355 dupl (Tebtynis, in the Arsinoitesnome, 1 CE) contains the same kind of provision for oil. The text, consisting of a contract between Heron, son of Haryotes, and the weaver Harmiysis, son of Petesouchos, stipulates that Harmiysis will work for Heron for a period of 2 years and that Heron will pay Harmiysis, as part of the payment for his labour, an annual amount of 28 drachmae for oil (i.e. approximately 14 obols or 2 drachmae and 2 obols per month). Although these texts give an indication of the monthly amount expected for oil, it cannot be used to indicate monthly consumption, simply because one cannot assume that the expected amounts covered the total expenditure for the monthly use of oil. What the text affirms, however, is that oil was such a necessary commodity that it was most probably common that wills and payment agreements made explicit provision to cover the cost of the use of oil.

There are, however, documented papyri that can help to indicate the approximate daily use of oil per individual. In the above, reference was already made to SB 3.6796, in which the entourage of a certain Apollonius received a daily allowance of six-and-a-quarter kotyle of lamp oil, that is, 1.5 L a day, equalling 12.3 obols. Several other papyri that have expense accounts as content contain the same kind of information. In P. Cair. Zen. 4.59704.30 (Philadelphia, in the Arsinoitesnome, 263-229 BCE), it is indicated that Apollonios' employees were given an allowance of 4 obols per day for castor oil (0.5 L per day, equalling 4 obols per day). P. Mich. 2.123 (Tebtynis, from the Arsinoitesnome; 46 CE), an account of the expenditure of Kronion, son of Apion, and his colleague Eutychas for the period 14-24 December 46 CE, indicates that their total expenditure on oil for the 10 day period was 349 obols, that is, 0.423 L per person per day, equalling a cost of 3.5 obols per day. P. Mich. 2.127 (Tebtynis, from the Arsinoitesnome; 46 CE) finally gives a figure of 180 obols for the expenditure on oil by Kronion and Eutychas for the period between 01 September 45 and 17 January 46 CE (i.e. 1.5 obols per day).

The above papyri indicate the expenditure on oil as between 1.5 and 4 obols per day. These figures, however, only give evidence of the use of oil for cooking because the daily expenditure in these texts is almost always given with the cost of food (e.g. vegetables) or the preparation of food. Interestingly, P. Mich. 2.123 mentions that on three specific evenings, the respective amounts of 4, 2 and 2 obols were spent on oil for the night scribes, and P. Mich. 2.128.24 indicates the cost of 4 obols of oil for night scribes on 19 September 46 CE. Clearly, lighting was expensive, increasing the amount an individual had to spend on oil. The remark of Vearncombe (2014:321), namely, that the woman's lighting of the lamp to search for a coin with the value of 1 drachma, is therefore significant, especially in a subsistence-level circumstance. As will be indicated below, what it indeed was 'not a negligible or insignificant action' (Vearncombe 2014:321).

The Lost Coin and Q

Several scholars have noted that one of the typical stylistic features of Q is the tendency to pair men with women by means of gender-paired illustrations (gendered doublets; see Arnal 1997:75-94; Batten 1994:47-49; Kloppenborg 2000:97; Vearncombe 2014:312). Although scholars do not always agree on the number of gendered doublets in Q, the following doublets are normally indicated: Q 11:31-32 (Queen of the South and men of Nineveh), Q 12:24-28 (those who farm and those who spin), Q 12:51-53(father against son, mother against daughter), Q 13:18-21 (the parables of the Mustard Seed and Leaven; a man sowing and a woman making bread), Q 15:4-10 (the parables of Lost Sheep and Lost Coin; a man losing a sheep and a woman losing a coin),Q 17:27 (marrying and being married) and Q 17:34-35 (two men on one couch and two women grinding).24

Although Q 15:4-10 (the parables of Lost Sheep and Lost Coin) is included as one of the gendered doublets in Q, Q 15:8-9 (the parable of the Lost Coin) is a debatable parable when it comes to Q. Some scholars argue that the Lost Coin is either Lukan Sondergut (see, e.g., Fitzmyer 1985:1073; Hultgren 2000:64; Manson 1951:283) or a Lukan creation as a sequel to the parable of the Lost Sheep (Lk 15:4-7) (see, e.g., Bultmann 1963:171; Fleddermann 2005:772; Goulder 1989:604). Kloppenborg (2000:96-98), however, has argued convincingly that the Lost Coin should be considered as being part of Q. Firstly, like the other gendered doublets in Q, the parable is associated with the Lost Sheep in Q.25 Secondly, the basic structure of the Lost Coin is parallel to the Lost Sheep in Luke, a consistent feature of the gendered doublets in Q. Thirdly, the possibility of the Lost Coin stemming from L (Lukan Sondergut) is 'extremely unlikely' because it would be incredible that 'Q and some completely independent source would contain two parables that were almost in identical form' (Kloppenborg 2000:97). Also, it is important for inclusion in Q that both parables cohere with the poor village or small-town environment reflecting the socio-economic situation of Q.26 Finally, the parable was most probably omitted by Matthew because it would have been difficult to use the parable, like the parable of the Lost Sheep, in the context of pastoral exhortation in which he uses the Lost Sheep.27 Based on these arguments, in the following it is assumed that the Lost Coin is part of Q.

The Lost Coin: A realistic reading

Positioning the Lost Coin in Q, as part of a gendered doublet, has a definite bearing on its possible meaning, as is the case with the other gendered doublets in Q. In Q 11:31-32, the Queen of the South will rise up with the men of this generation at the judgement and condemn them; so will the men of Nineveh. In Q 12:24-28, those who farm should be like the ravens who do not farm. They are not anxious because God feeds them.

This should also be the attitude of those who spin. Because Jesus brings division, father will turn against son and therefore mother against daughter (Q 12:51-530). In the days of the Son of Man, men will be given in marriage as will women (Q 17:27), and one man will be taken from two lying in bed. So, it will be with two women grinding (Q 17:34-35). What happens or will happen in the first part of the doublet, happens or will happen in the second part. In other words, the meaning of the second part of the doublet is determined by the first part. As suggested by Kloppenborg (2014a:542): '[t]he pairing of the parables (and other sayings of Jesus), which perhaps first took place in the Sayings Gospel, represents an important interpretive manoeuvre'.

This is especially clear from Q 13:18-21, the parables of the Mustard Seed and Leaven, and very importantly, two parables as is the case in Q 15:4-10 (the parables of Lost Sheep and Lost Coin). A clue to interpret these two parables, apart from their placement as a double illustration, is the way in which they are structured. The structure of the Mustard Seed is paralleled in the Leaven,28 and the creation of this parallel stresses that the kingdom of God is the focus on both parables, specifically its rapid and dramatic growth (see Kloppenborg 2014a:543). This is also the point of view of Arnal and Roth: what links the couplet is the fact of growth (Arnal 1997:82), or 'what is insignificant and hidden … will grow and be marvelously revealed' (Roth 2018:324). Elsewhere, I have presented a realistic reading of the Mustard Seed and argued that the Q-version of the parable (Q 13:18-19), because it does not contain the smallest-largest comparison, is not a parable of growth. Rather, the kingdom is compared to a mustard seed planted in a garden, meaning that the garden becomes polluted because of the law of diverse kinds. Moreover, once planted, a mustard seed turns into a shrub that tends to take over because it very soon grows out of control. As such, as a comparison to the kingdom, the kingdom is polluted, includes the impure and takes over (Van Eck 2016:79-83; see also Crossan 1991:278-279). When this interpretation of the Mustard Seed is applied to the parable of the Leaven (Q13:20-21), it confirms Q's 'important interpretive manoeuvre': leaven (a symbol of moral evil, corruption and uncleanness; Scott 2007:95-119) hid in three pecks of meal turns that what is unleavened (pure) to what is leavened (i.e. impure, corrupt and unclean): a process that cannot be stopped. Thus, again, the kingdom is compared with that what is polluted and impure, that what is out of control and that what cannot be stopped until everything is corrupt and unclean (ἕωςοὗἐζυμώθηὅλον; Lk 3:21). As such, the meaning of the Leaven parallels that of the Mustard Seed. A garden becomes impure, wheat also becomes impure. And that what makes the garden and wheat impure is out of control and cannot be stopped.

Is this also the case with the parables of the Lost Sheep and Lost Coin? Does the meaning of the parable of the Lost Sheep also preempt the meaning of the Lost Coin? Using social realia invoked by these two parables, attested by available papyri, it seems to be the case. The social and economic registers presupposed by the Lost Sheep, attested by social comparanda provided by available documented papyri, are that a flock of hundred sheep was a medium-sized flock that most probably belonged to one or more than one owner, and that shepherds were contracted to care for the flock. The sheep thus did not belong to the shepherd who practised a despised trade. Shepherds were rendered unclean and seen as robbers, criminals and thieves; were unsupervised, transient and armed; and were often associated with bandits and agitators.

Wages paid to shepherds were poor, and the intrinsic value of a sheep, relative to a shepherd's wage, was high. Shepherds earned more or less 16 drachmae per month, and the intrinsic value of a male sheep was more or less 10 drachmae and that of a female sheep was 18-20 drachmae. Thus, because shepherds were held accountable for livestock losses, the shepherd had no other option to go and look for the lost sheep. By doing this, he took a huge risk by leaving 99 sheep behind. Finding one lost sheep could also mean losing the 99 sheep left behind. The chance he took, however, paid off. A lost sheep was found, wages were secured and when the shepherd went home after his contract expired, there was reason to celebrate. As such, the kingdom became visible in the risky and unexpected action of an unexpected person. A despised shepherd by taking a chance ensured that everybody has enough. Seeking, which could have resulted in losing, resulted in gaining.

In the parable of the Lost Coin, the same theme of gaining or losing is present. In the Lost Sheep, the focus is on the actions of a shepherd, and in the Lost Coin, the focus is on the actions of a woman. In both parables, this is unexpected - a despised shepherd and a female, not a male. The social background of the shepherd and the woman based on papyrological evidence is the same. A shepherd's wage of 16 drachmae per month was well below a poverty-level income (Van Eck 2016:137), and given the relative value of 10 drachmae and the woman's behaviour regarding the 1 drachma in the parable, she is also poor (Vearncombe 2014:318): someone 'living at or near subsistence' (Vearncombe 2014:336).29 In both cases, when the sheep and drachma get lost, a risk is taken to find that what was lost. The shepherd risks 99 sheep for the sake of one, and the woman risks 9 drachmae for the sake of one. Why?

As demonstrated by available papyrological evidence, the price of oil used for lighting was more or less 10 obols per litre in the 1st century, with the cost of cooking and food between 1.5 and 4 obols per day. Lighting a lamp for a night or part of a night seems to amount to 2-4 obols. Thus, looking for a coin with the worth of 1 drachma easily could have cost more than 1 drachma if not found soon after a lamp was lit. Looking for one sheep risked the loss of 99 sheep, and lighting a lamp risked the loss of 9 drachmae.

This is why the woman's search is described with the adverb ἐπιμελῶς (Q 15:8). Contra Vearncombe (2014:322-323) and Hultgren (2000:67),30 the woman's search is described as diligently because she has to find the lost coin as soon as possible. If not performed attentively or carefully, the search can cost more than what was lost. Then this is also the reason why she rejoices and celebrates with her female friends and neighbours (τὰςφίλας καὶ γείτονας; Lk 15:9) when she finds the lost coin. The risk she took paid off; less was spent on what was found. And therefore, as is the case in the Lost Sheep, she invites her friends and neighbours to come and rejoice with her (συγχάρητέμοι; Q 15:9; see Q 15:6 for the Lost Sheep). Because of the risk she gained, and now everybody has enough. The kingdom is visible in the risky and unexpected action of an unexpected person. A poor woman, by taking a chance to end up with even less that she has, ensured that everybody has enough.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author has declared that no competing interests exist.

Author(s) contributions

I declare that I am the sole author of this research article.

Ethical consideration

This article followed all ethical standards for a research without direct contact with human or animal subjects.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of any affiliated agency of the author.

References

Aristophanes, 1925, Lysistrata, Thesmophoriazusae, Ecclesiazusae, Plutus, transl. B.B. Rogers, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. [ Links ]

Arnal, W.E., 1997, 'Gendered couplets in Q and legal formulations: From rhetoric to social history', Journal of Biblical Literature 116(1), 75-94. https://doi.org/10.2307/3266747 [ Links ]

Bailey, K.E., 1976, Poet and peasant: A literary-cultural approach to the parables in Luke, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Batten, A., 1994, 'More queries for Q: Women and Christian origins', Biblical Theology Bulletin: A Journal of Bible and Theology 24(2), 44-51. https://doi.org/10.1177/014610799402400202 [ Links ]

Bazzana, G.V., 2011, 'Basileia and debt relief: The forgiveness of debts in the Lord's Prayer in the light of documentary papyri', The Catholic Biblical Quarterly 73(3), 511-525. [ Links ]

Bazzana, G.V., 2014, 'Violence and human prayer to God in Q 11', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 70(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v70i1.2733 [ Links ]

Bishop, E.F.F., 1955, Jesus of Palestine: The local background to the gospel documents, Lutterworth Press, London. [ Links ]

Blomberg, C.L., 2012, Interpreting the parables, InterVarsity Press, Downers Grove, IL. [ Links ]

Boucher, M.I., 1981, The parables, Michael Glazier, Inc., Wilmington, DE. [ Links ]

Bultmann, R., 1963, History of the synoptic tradition, transl. J. Marshall, Blackwell, Oxford. [ Links ]

Catchpole, D.R., 1993, The quest for Q, T&T Clark, Edinburgh. [ Links ]

Crossan, J.D., 1991, The historical Jesus: The life of a Mediterranean Jewish peasant, HarperCollins Publishers, San Francisco, CA. [ Links ]

Crossan, J.D., 2012, The power of parable: How fiction by Jesus became fiction about Jesus, HarperOne, New York. [ Links ]

Dodd, C.H., 1961, The parables of the kingdom, Charles Scribner's Sons, New York. [ Links ]

Fitzmyer, J.A., 1985, The Gospel according to Luke X-XXIV: Introduction, translation, and notes, Doubleday, New York. [ Links ]

Fleddermann, H.T., 2005, Q: A reconstruction and commentary, Peeters Publishers, Leuven. [ Links ]

Goulder, M.D., 1989, Luke: A new paradigm, Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield. [ Links ]

Grenfell, B.P. & Mahaffy, J.P., 1896, The revenue laws of Ptolemy Philadelphus, Clarendon, Oxford. [ Links ]

Hayden, B., 2018, 'Price formation and fluctuation in Ptolemaic Egypt', PhD thesis, University of Chicago, Dept. of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, Chicago, IL. [ Links ]

Hultgren, A.J., 2000, The parables of Jesus: A commentary, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Jeremias, J., 1972, The parables of Jesus, transl. S.H. Hooke, SCM Press, London. [ Links ]

Kirk, A.K., 1998, The composition of the Sayings Source: Genre, synchrony, and wisdom redaction in Q, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Kistemaker, S.J., 1980, The parables: Understanding the stories Jesus told, Baker Books, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Kloppenborg, J.S., 2000, Excavating Q: The history and setting of the Sayings Gospel, Fortress Press, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Kloppenborg, J.S., 2006, The tenants in the vineyard: Ideology, economics, and agrarian conflict in Jewish Palestine, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen. [ Links ]

Kloppenborg, J.S., 2014a, Synoptic problems: Collected essays, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen. [ Links ]

Kloppenborg, J.S., 2014b, 'The parable of the burglar in Q: Insights from papyrology', in D.T. Roth, R. Zimmermann & M. Labahn (eds.), Metaphor, narrative, and parables in Q, Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungenzum Neuen Testament 315, pp. 287-306, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen. [ Links ]

Koester, H., 1990, Ancient Christian gospels: Their history and development, Trinity Press International, Harrisburg. [ Links ]

Lambrecht, J., 1981, Once more astonished: The parables of Jesus, Crossroad, New York. [ Links ]

Levine, A.-J., 2014, Short stories by Jesus: The enigmatic parables of a controversial rabbi, HarperOne, San Francisco, CA. [ Links ]

Liddel, H.G. & Scott, R., 1968, 'χοῦς', in H.G. Liddel & R. Scott (eds.), A Greek-English lexicon, p. 2000, Clarendon Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Loisy, A.F., 1908, Les évangilessynoptiques, Chezl'auteur, Ceffonds, PrèsMontier-en-Der. [ Links ]

Manson, T.W., 1951, The sayings of Jesus, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Maresch, K., 1996, Bronze und Silber: Papyrologische Beiträgezur Geschichte des Währungimptolemäischen und römischen Ägyptenbiszum 2. Jahrhundert n. Chr., Westdeutscher Verlag, Cologne. [ Links ]

Merz, A., 2007, 'Last und Freude des Kehrens (Von der verlorenenDrachme) - Lk 15,8-10', in R. Zimmermann, D. Dormeyer, G. Kern, A. Merz, C. Münch & E.E. Popkes (eds.), Kompendium der GleichnisseJesu, pp. 610-617, Gütersloher Verlagshaus, München. [ Links ]

Montefiore, C.G., 1909, The synoptic gospels, MacMillan, London. [ Links ]

Morgan, G.C., 1953, The parables and metaphors of our Lord, Marshall, Morgan & Scott Ltd., London. [ Links ]

Oakman, D.E., 2008, Jesus and the peasants, Cascade Books, Eugene. [ Links ]

Pestman, P.W., 1994, The new papyrological primer, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Polag, A., 1979, Fragmenta Q: Textheft zur Logienquelle, NeukirchenerVerlag, Neukirchen-Vluyn. [ Links ]

Roth, D.T., 2018, The parables in Q, T&T Clark, New York. [ Links ]

Sandy, D.B., 1989, The production and use of vegetable oils in Ptolomaic Egypt, Scholars Press, Atlanta, GA. [ Links ]

Scott, B.B., 1989, Hear then the parable: A commentary on the parables of Jesus, Fortress Press, Minneapolis. [ Links ]

Schottroff, L., 2006, The parables of Jesus, transl. L.M. Maloney, Augsburg Books, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Schröter, J., 1997, Erinnerungan JesuWorte: Studienzur Rezeption der Logienüberlieferung in Markus, Q und Thomas, Neukirchener Verlag, Neukirchen-Vluyn. [ Links ]

Scott, B.B., 2007, 'The reappearance of parables', in E.F. Beutner (ed.), Listening to the parables of Jesus, Jesus Seminar Guides 2, pp. 95-119, Polebridge Press, Santa Rosa, CA. [ Links ]

Smith, W.C.A., 1951, A new classical dictionary of Greek and Roman biography, mythology, and geography partly based upon the dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology, Harper & Brothers, New York. [ Links ]

Snodgrass, K.R., 2008, Stories with intent: A comprehensive guide to the parables of Jesus, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Van Eck, E., 2016, The parables of Jesus the Galilean: Stories of a social prophet, Cascade Books, Eugene, OR. [ Links ]

Van Eck, E., 2017, 'Realism and method: The parables of Jesus', Neotestamentica 51(2), 163-184. https://doi.org/10.1353/neo.2017.0010 [ Links ]

Van Eck, E. & Kloppenborg, J.S., 2015, 'The unexpected patron: A social-scientific and realistic reading of the parable of the Vineyard Laborers (Mt 20:1-15)', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 71(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v71i1.2883 [ Links ]

Van Eck, E. & Van Niekerk, R.J., 2017, 'Life in its unfullness: Revisiting ἀναίδειαν (Lk 11:8) in the light of papyrological evidence', Verbum et Ecclesia 38(3), 135-149. https://doi.org/10.4102/ve.v38i3.1647 [ Links ]

Van Eck, E. & Van Niekerk, R.J., 2018, 'The Samaritan "brought him to an inn": Revisiting πανδοχεῖον in Luke 10:34', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 74(4), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v74i4.5195 [ Links ]

Vearncombe, E.K., 2014, 'Searching for a lost coin: Papyrological backgrounds for Q 15,8-10', in D. Roth, R. Zimmerman & M. Labahn (eds.), Metaphor, narrative, and parables in Q, Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungenzum Neuen Testament 315, pp. 307-337, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen. [ Links ]

Weder, H., 1984, Die Gleichnisse Jesuals Metaphern: Traditions- und Redaktionsgeschichtliche Analysen un Interpretatonien, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen. [ Links ]

Zimmermann, R., 2007, 'Die Gleichnisse Jesu: Eine Leseanleitung zum Kompendium', in R. Zimmermann, D. Dormeyer, G. Kern, A. Merz, C. Münch & E.E. Popkes (eds.), Kompendium der Gleichnisse Jesu, pp. 3-45, Gütersloher Verlagshaus, München. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Ernest van Eck

ernest.vaneck@up.ac.za

Received: 23 July 2019

Accepted: 14 Aug. 2019

Published: 14 Nov. 2019

1. See also Zimmermann (2007:25): 'EineParabel is einkurzernarrativer … fiktionaler Text, der in der erzählten Welt auf bekannte Realität … bezogenist'. Hultgren (2000:9) is of the same opinion: '[t]he subject of the parables is typically the familiar everyday life: men and women working, losing, and finding; fathers and sons in strained and joyous relationships; kings, rich men, and slaves in stereotypical roles; domestic animals, seeds, plants, vineyards, leaven, and the like'.

2. See Hultgren (2000:66): 'Does [the women] live alone and own [the house] as a private dwelling (which would indicate wealth)? Is it provided for her? Does she live with others in the house, or does she have an apartment within a house? Does she have other assets? Is she a widow?'

3. Snodgrass (2008:113) describes the woman as 'probably just a typical woman one would find in any Galilean village'. What this means, and on what evidence this is based, is not clear.

4. This rough equivalency is confirmed by Josephus in his Jewish Antiquities 3.8.2 and 18.9.1 (see Hultgren 2000:66).

5. The answer to this question obviously relates to a reading of the parable in the originating setting it was first told by Jesus (27-30 CE), or a reading of the parable in its literary setting in Luke (or Q). With regard to the latter, the following remark of Kloppenborg (2014a:515) cannot be relevant enough: '[i]t is clear from the editing of the parables by the Synoptic evangelists themselves that they did not treat the parables as fresh and lively narratives, combining the everydayness of Palestinian village society with playful inversions and resonant metaphors; instead, the parables offered mere surfaces upon which to inscribe instructions on salvation history, Christology, ecclesiology and morals'.

6. See P. Mich. 5.355, P. Col. 4.66, P. Cair. Zen. I.59028, IV.59748; P. Lond. I.131 (Vearncombe 2014:318-319).

7. In Oakman's (2008:44) estimate, 2 denarii represents about 3 weeks' worth of food for one person, and in terms of a family of four people, 2 denarii would represent about a week to a week and a half worth of food. A year's supply of food for a family of four people thus required between 60 and 122 denarii. If other necessities such as clothes, taxes and religious dues are also taken into consideration, 250 denarii per annum (22 denarii per month) was a poverty-level income. Vearncombe (2014:319) more or less concurs with Oakman (2008) in her estimate: 300 denarii would have been an annual subsistence wage for a family of six people.

8. See also Liddel and Scott (1968:2000), where the volume of a χοῦς is equalled to 12 κοτύλαι.

9. κοτύληδέἐστινεἶδοςμέτρου, ὅ λέγομενἡμεῖςἡμίξεστον A kotyle is a kind of measure, which we say is a half xeston (Aristophanes 1925:436b.). For other Roman units of measurements, see Smith (1951:1024).

10. Smith (1951:1024) is of the opinion that 1 chous is equal to a volume of 3.27 L. Vearncombe's measurement of 1 kotyle as equalling 0.27 L is most probably based on Smith's estimated volume of 1 chous. In what follows, Pestman and Hayden's measure of 1 chous is used, that is, 1 chous is equal to2.9 L.

11. P. Rev. 40.12 and 14 read as follows: 12 τὸμμετρητὴντὸν [δωδε]κάχουν (δραχμῶν) μη (= 12 drachmae per metretes) 14 … τὴνδὲκοτύλην (διωβόλου) (= 2 obols per kotyle) 15 … τὴνδὲκοτύλην (διωβόλου) … (= 2 obols per kotyle)

12. The price per litre is calculated by using the volumes in Table 1, with 1 drachma equalling 6 obols. In this case, for example, 48 drachmae equal 288 obols, divided by 1 metretes (34.8 L), equalling 8.275 obols per litre.

13. P. Col. Zen I 21.4 reads as follows: 'ἢ [τὸ] κίκ̣[ι] ἢ τὴντιμὴν (δραχμὰς) δ. καὶ ἀποδότωΚρότωι'.

14. P. Oxy. 4.736.15 reads as follows: 'κβ. ἐλαίουχο(ὸς) α (δραχμαὶ) δ (τετρώβολον)'.

15. P. Fay 101 v.1.9 reads as follows: '(γίνονται) (δραχμαὶ) κθ. καὶτιμ(ῆς) ἐλαίου χοί(νικος) α (δραχμαὶ) ε'.

16. In calculations to follow pertaining the daily use of oil, the figure of 8.2 obols per litre (1 drachma and 2 obols) will be used.

17. See BGU 13.2306 (51 CE), BGU 13.2307 (1st century) and BGU 13.2309 (99-100 CE), all from Soknopaiu Nesos in the Arsinoitesnome.

18. See, for example, O. Berenike 1.4 (26-75 CE), O. Berenike 1.26 (25-75 CE), O. Berenike 1.28 (33-70 CE) and O. Berenike 1.87 (26-75 CE).

19. In P. Tebt. III, pt. I 703.174-182 (Tebtynis, in the Arsinoitesnome; 210 BCE), Zenodoro, the dioiketes, gives instructions to the oikonomos that oil should not be sold for more than the fixed price: π̣ο̣υςδι̣α̣ρίπτειν.μελέτωδέσοι καὶ̣ [ἵ]ν̣α̣ τ̣ὰ̣ [ὤ-] 175 ν̣ι̣α̣ μὴ πλείονος πωλῆται τῶνδιαγεγραμ- [μ]ένωντιμῶν· ὅσα δʼἂνἦιτιμὰςοὐχἑστη- [κ]υ̣ίας ἔ̣χ̣ο̣ντα, ἐπὶ δὲτοῖςἐργαζομένοις [ἐσ]τὶν τ̣[άσ]σ̣ειν \ἃς/ ἂν βο[ύ]λωνται, ἐξεταζέσ- [θ]ω καὶ τοῦτομὴ παρέργως, καὶ τὸσύμ 180 μετρον ἐπιγένημα 〚τα〛τάξας τῶν πω- [λ]ουμένωνφ̣ο̣ρ̣τίωνσυνανάγκα〚ι̣〛ζ̣ε̣ τ̣ο̣ὺ̣ς̣ .[.]..κ̣ο̣υ̣[..].ς̣ τ̣ὰςδιαθέσεις ποιεῖσθα[ι]. [Take care that commodities not be sold for more than the prices fixed by ordinance. Examine closely all thos e which do not have fixed prices, and those for which it is up to the traders to set (the price) as they wish, and after you prescribe a moderate profit for the goods that are being sold, you must make the … dispose of them] (transl. from Hayden 2018:211).

20. See Chr. Wilck. 300.14 (Alexandria; 217 BCE): ὯροςἉρμάει χαίρειν. προσπέπτωκέ μοι παρὰ πλειόνωντῶνἐκτοῦνομ[οῦ] καταπεπλευκότωντὸἔλαιον π[ωλ]εῖσθαι πλείονοςτιμῆςτῆςἐντῶι προστάγμα[τι] διασεσαφημένης, παρὰδὲσοῦοὐθ[ὲ]ν ἡμῖν προσπεφώνηται οὐδʼἸμούθηι τ[ῶι] υἱῶι ἐπὶ τῶντόπων μεταδεδώκα[τ]ε [Horos to Harmais, greeting. I have heard from many of those who have sailed down from the nome that oil is being sold at a higher price than what was made clear in the ordinance, but nothing from you has been reported to me, nor have you communicated to Imouthes my son, who is on location] (transl. from Hayden 2018:212).

21. See, for example, O. Mich. 1.55 (Arsinoites; 6 CE) and O. Mich. 2.772, 774 and 775 (Karanis, in the Arsinoitesnome; 2 BCE).

22. See, for example, C. Pap. Gr. 1.9 (Alexandria; 5 BCE) and C. Pap. Gr. 1.24 (Oxyrhynchus; 87 CE), for contracts with nurses, and C. Pap. Gr. 1.13 (Alexandria; 30 BCE-14 CE) and P. Ryl. 2.178 (Hermopolis; 127 CE) for contracts relating to the rearing of children.

23. If we take the cost of oil as 8.2 obols per litre, it comes down to a payment of 2 drachma (1 drachma and 5.1 obols) per month.

24. Batten (1994:47-49) lists the six instances mentioned, Arnal (1997:82) adds Q 7:29-30, 34 (Jesus' association with tax collectors and prostitutes) and Q 14:26-27(in which one is exhorted to hate father and mother, son and daughter) to Batten's list, while Kloppenborg (2000:97) and Vearncombe (2014:312) exclude Q 12:51-53 from the list of Batten.

25. According to Schröter (1997:321, n. 76) and Roth (2018:320), it is difficult, if not impossible to ascertain the precise location of the parable of the Lost Coin in Q. Kirk (1998:304), however, argues the opposite. See also Crossan (2012:38), who calls the parables of the Lost Sheep and Lost Coin in Q a 'deliberate pair'.

26. See also Vearncombe (2014:314-324), who indicates that typical social realia offered by papyrological evidence grounds the parable in the social location of Q.

27. See Loisy (1908:138), Montefiore (1909:984), Polag (1979:26, 72), Lambrecht (1981:38-41), Weder (1984:170), Koester (1990:148) and Catchpole (1993:190-194) who argue for the inclusion of the Lost Coin in Q.

28. Both are introduced by a question, the formula introducing the comparison is similar, both involved an agent that takes mustard or leaven, both of the principal verbs are aorist, both represent unusual choices, both focus on the element of growth and in both cases the result is extraordinary (see Kloppenborg 2014a:54).

29. It is not stated in the parable that the woman was married or lived on her own. If she lived on her own, and therefore was responsible for the income of the family (like the shepherd), her situation would have even been more desperate (Bailey 1976:103-104).

30. According to Vearncombe (2014:322-323), the adverb ἐπιμελῶς was added by Luke to facilitate a metaphorical interpretation of the parable. It becomes 'the interpretative key for the metaphoric understanding of the parable', that is, the woman as a symbol for God. Hultgren (2000:67) describes the woman as ἐπιμελῶς because she has to light a lamp in a house that has no windows or natural lighting.