Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

HTS Theological Studies

On-line version ISSN 2072-8050

Print version ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.75 n.1 Pretoria 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v75i1.5342

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

The online educated or online indoctrinated human? Discourse analysis as a method to study ideologies disseminated by online courses

Iuliia PlatonovaI; Ignatius G.P. GousII

ISt. Tikhon's Orthodox University, Moscow, Russia

IIDepartment of Biblical and Ancient Studies, College of Human Sciences, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Online courses attract thousands, even millions of students from all corners of the Earth. As such, they have the potential to educate many people. Education, however, is not neutral. Knowledge is embedded in contexts and perspectives, carrying ideological baggage, and so is teaching and learning. Teaching can no longer be the mere provision of content. The knowledge explosion implies that the ability to master content should become part and parcel of the course curriculum. In the same vein, the fact that online courses attract students from many different contexts necessitates that lecturer and student alike should be aware of the underlying ideologies in the course content. To this end, in this conceptual article it is argued that discourse analysis of not only the written course content but also of images used to illustrate the content can be helpful; these are often not scrutinised for ideological baggage. If not, the online educated human might become the online indoctrinated human, to the detriment of all.

Keywords: Online education; MOOC; Implicit ideology; Discourse analysis; Pedagogic discourse.

Introduction

Online courses attract millions of students worldwide. These courses are presented by many reputable and traditional universities, and as they are available online and often with open access they attract students from all over the globe. The upside of this is that everyone with access to technology has the potential to become an online educated human, through access to information and training.

There is a conceptual question to consider, though. Traditional face-to-face teaching and training usually takes place within a context, with knowledge being locally relevant. Online courses, in their massiveness, however, attract students from every corner of the Earth. Is it possible to make the taught knowledge contextually relevant to each of them? How dominant is the context from where it is transmitted in the course? Are the lecturers and the students enrolled in the online courses aware of possible local biases? In short - do online courses lead to online educated humans or to online indoctrinated humans?

Audio and video recordings of university lectures are available to anyone with access to the Internet. In recent years the opportunity to take open-source, free knowledge has appeared, being embedded in the form of education platforms that partner with top universities and organizations worldwide, to offer courses online for anyone to take. These courses provide high visual quality, fitted out with professionally recorded lectures, interactive tasks, discussions, forums, quizzes and up-to-date reading materials. What distinguishes them from e-learning courses is their availability - they are open and in many cases free. The only requirement is having Internet access, and anyone can subscribe to these online courses and obtain the knowledge.

Open education as a concept promoting open, accessible educational resources introduces some learning advantages: the opportunity to get in touch with well-known professors, become familiar with the practices of internationally recognised universities - all of this, in many cases, free of charge. 'Open' also means flexible: no longer reading and completing tasks in a pre-determined curricular order; rather having a hands-on educational experience, the right to choose your own educational path, learning in the open pedagogic atmosphere, studying what you need and when you find learning convenient. Learning philosophy considers such education as the way to foster free-thinkers who are responsible for their choices and actions (Nyberg 1975). UNESCO believes that universal access to high-quality education is a key to the building of peace, sustainable social and economic development, and intercultural dialogue (UNESCO n.d.a).

On the other hand, open educational resources are recognised as one of the tools to compete for talented students and spread ideological influence. For example, according to Altbach, the human and social sciences are especially prone to be ideologically tinged, thereby spreading ideological content together with the course content. According to him, we have to ask 'who controls the knowledge and why does it matter?', as well as, 'The question is still up in the air - are MOOCs ideologically tinged and if so, how are we to grasp ideology beyond the scientific discourse' (2014:4).

Inasmuch as discourse, including that deployed in educational practices, is socially and culturally specified, we assume that implicit ideology is an unavoidable feature of pedagogy (Bernstein & Solomon 1999; Gee 2011; Giroux 1990; Schmid 1981; Van Dijk 1998). Thus, the objective of the article is twofold:

1. to define the characteristics of discourse, verbal and symbolic forms of knowledge representation commonly employed in online courses

2. to explore approaches and strategies enabling lecturers and learners to become aware of overt and hidden ideological elements in the texts and images while engaging with course material.

The goal is therefore not to deconstruct the ideological positions of specific online courses, as has been done by Selwyn, Bulfin and Pangrazio (2015) and Ebben and Murphy (2014). It is rather to sensitise and empower lecturer and learner alike to use the tools of discourse analysis to evaluate the possible ideological content of online courses stemming from contexts differing from their own.

Educational and pedagogic discourse and online courses

If discourse is language in its textual form used in the social context (Van Dijk 1989) or a 'distinctive way to use language' (Gee 2011), then what do we imagine when we think about discourse in education? The first images appearing in your mind are probably a teacher presenting a lecture in a classroom, the textbooks teachers refer to, and written and/or verbal answers of learners. There images, however, are reflections of behaviourist and cognitivist learning theories. Keeping in mind the particularities of connectivist theory and the educational model applied in online courses, one could certainly imagine a different picture of what educational discourse is.

However, before we come back to the issue of discourse in education, some extracts from the theory of discourse are presented.

What is discourse?

First of all, discourse is not only a text or language itself. Discourse is also a way, a mode or a manner:

-

'to manifest or hide desires, to translate struggles of domination' (Foucault 1981:52)

-

of 'interaction playing a role as the preferential site for the explicit, verbal formulation and the persuasive communication of ideological propositions' (Van Dijk 1995:17)

-

to use language (Gee 2011).

Discourse is a part of 'its local and global, social and cultural contexts' (Fairclough 1995:29). At the same time discourse is a text that cannot be understood without its context, what Bogutzkaya (2009:45) depicts with the following formula: 'discourse = context + text'. Discourse is not only text as in word format, but art and images as a way to communicate knowledge is discourse as well (Rose 2001).

Discourse is a complex phenomenon and hardly definable in a single precise way. Even so, discourse is a socially and culturally specified representation of reality by means of text. The way discourse makes and shares meaning in using text and image is always context-bound and reflecting the social and cultural horizon it stems from (Bakhtin 1981:269; Hodge & Kress 1988). Therefore, for the purpose of this article, the most significant features of discourse are seen to be the following:

1. Discourse is a social phenomenon.

2. Discourse is never free from values, beliefs, convictions.

3. Discourse is to represent, transmit, and create meanings.

4. Discourse is wider then text and may be presented in images, symbols, sounds and any other way enabling a transmitter to represent reality to a receiver.

5. Discourse is socially specified and may be classified depending on the social area where it is presented.

Types of discourse in context

Considering different occasions when one communicates with others during the day, it is not hard to notice that the ways that representations are shared in different contexts and on different occasions are different as well.

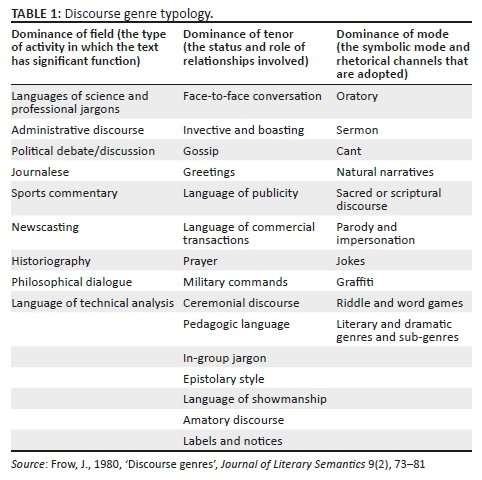

For example, one who is ideologically a liberal by conviction represents liberal values, reflecting upon that while speaking with relatives, communicating in the office, writing an email to a friend and so on. Frow (1980), referring to Halliday (1978), classifies discourse genres by the criteria of field, tenor and mode (Table 1). Field is about the subject matter or content that is being discussed. The tenor describes the social relation between the participants in discourse and includes relations such as formality, power and affect.

Mode refers to the chosen channel of communication, such as talking, writing or a YouTube video.

Gee (2011) defines different language styles, namely vernacular and non-vernacular. Vernacular languages are so-called everyday languages. They are biologically conditioned and express the general, not a situation-specific meaning. Non-vernacular languages, on the contrary, are specified by the area of application. They are socially conditioned, obtained by means of education or learning from experience of social interaction. Non-vernacular languages have situated meaning or even a range of meanings; they cannot be properly understood without knowing the context.

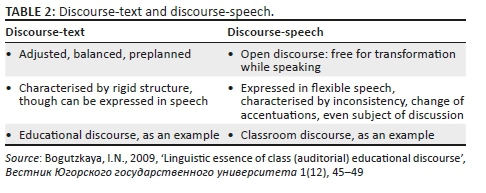

Bogutzkaya (2003), referring to Van Dijk, distinguishes between discourse-text and discourse-speech (Table 2).

When discourse-text and discourse-speech are presented depends on the purposes of the presenter or transmitter. To create meaning, discourse-speech, which is open, flexible and inconsistent, is required. On the other hand, in order to transmit meaning, discourse-text is probably a more suitable option.

When discussing ways to spread meaning and power, it is important to also mention Van Dijk's typology of discourse (1989):

1. Discourses that have directive pragmatic function (elocutionary force): commands, threats, laws, regulations, instructions and, more indirectly, recommendations and advice.

2. Persuasive discourse types: advertisements and propaganda. Aim at influencing future actions of recipients.

3. Descriptions of future or possible events, actions or situations: predictions, plans, scenarios, programmes and warnings, combined with different forms of advice.

4. Influential narrative, such as novels or movies, may describe the (un)desirability of future actions.

Thus, several classification criteria of discourse are defined:

1. social determinism (simple [everyday] or socially specified - relates to Gee's [2011] language styles)

2. area of implementation (what Frow [1980] calls 'field')

3. status (social role) of a transmitter (relates to Frow's [1980] 'tenor')

4. rhetorical method (relates to Frow's [1980] 'mode')

5. discourse flexibility (open or closed type - relates to Bogutzkaya's [2003] typology)

6. kind of influence (directed to emotions, critical thinking, will, values - relates to Van Dijk's [1989] power effects).

Taking into consideration the aforementioned criteria, the particularities of the educational discourse are presented in the following section.

Peculiarities of educational (pedagogic) discourse

Universities, together with the family, church and media, are the institutions transferring ideologies, values and beliefs (Van Dijk 1998). Teachers themselves have been raised in particular ideological conditions and, being educated within families and universities, they share values appropriate within society. They generally know what is expected from them and act in accordance with the dominant ideology (Schmid 1981). To clarify what educational discourse is, we begin with the definition of learning.

Learning is not only a mental thing but rather is:

a type of social interaction: knowledge is distributed across people and their tools and technologies, dispersed at various sites, and stored in links among people, their minds and bodies, and specific community groups. (Gee 2011:19)

Gee (2011) illustrates the following plausible reasoning: learning is to change social practices, change patterns of behaviour; social practices create 'socially situated identities'. What this means is that change in social practices leads to change in identities; the resulting conclusion is that learning causes 'change in socially situated identities'. Discourse, coexisting with learning, appears to have the power to initiate changes.

Thus, educational discourse is an influential mode to accomplish symbolic control and cultural production (Bernstein & Solomon 1999). Discourse applied in educational practices, according to Bernstein and Solomon (1999:269) theory of symbolic control, is projected from 'positions in the recontextualising arenas'. Bernstein and Solomon (1999) call such discourse pedagogic, because it is 'conditioned by the symbolic control mediated through pedagogic device'. Pedagogic relations in his theory are explained to exist in the following forms: explicit-implicit and tacit. The first form of pedagogic relations is characterised by the purposefulness of the pedagogic act, aimed at modification, development and change of knowledge. Tacit form is characterised by the fact that neither transmitter nor acquirer may be aware of knowledge change - unintentional pedagogy.

Bernstein and Solomon (1999) distinguish two discursive forms: horizontal and vertical. Horizontal discursive form is related to Gee's (2011) vernacular language style - it is everyday discourse, which, even if produced with the intention to change an acquirer's knowledge, nevertheless does not resemble a pedagogic act. This means that a transmitter does not evaluate the result of pedagogy - so performs a tacit form of pedagogic relations. Exemplifying horizontal discourse aimed at knowledge modification, Bernstein and Solomon (1999) describe media language, which is defined as 'quasi pedagogic discourse'. Conversely, vertical discursive form, like non-vernacular language, brings specialised knowledge. Such a socially specified discourse in its pedagogic modality is the realisation of symbolic control - it attempts to shape and distribute forms of consciousness, identity and desire. In other words, vertical discourse in pedagogic relations is always explicit or implicit; it is focused on knowledge change and controls the purpose if fulfilled.

Pedagogic discourse is manifested in two pedagogic modalities - official and local. In its official modality pedagogic discourse is reflected at the level of institutions: in regulation and evaluation practices.

Official pedagogic discourse, though institutionalised, is not limited to formal educational institutions; rather it includes medical, psychiatric, social service, penal, planning and informational agencies. Local pedagogic modalities are familial, peer and 'community' ones. Bernstein and Solomon's (1999) pedagogic modalities appear similar to North's (1991) formal and informal institutions. As with institutions, official and local pedagogic modalities, according to Bernstein and Solomon, coexist in the following relations with each other: colonising-complementary, conflicting and privileging-marginalising.

Thus, pedagogic discourse, modifying knowledge, distributing forms of consciousness and desire, changing socially situated identities, is to be perceived in a critical manner (Giroux 1990). Giroux, promoting critical pedagogy, states (1990:37):

1. Education produces not merely knowledge, but also political values and beliefs,

2. Ethics is a key component of critical pedagogy,

3. Critical pedagogy necessitates finding new ways of collecting knowledge across scientific disciplines,

4. Critical pedagogy emphasises the role of teachers as 'transformative intellectuals who occupy specifiable political and social locations'.

The last statement describes the pedagogic discourse that critical pedagogy has to be featured with, according to Giroux (1990). What has to be distributed by the pedagogic discourse of postmodernity as the era characterised by a 'plurality of truths' is extra-disciplinary knowledge, ethics and values. The typical teacher of postmodernity is an intellectual able to transform and change socially specified beliefs. Giroux (1990) through his postmodernist attitude allows us to distinguish the ideology influencing contemporary pedagogic discourse as the 'ideology of social reconstruction' (Schiro 2013).

The particularities of educational discourse are as follows:

1. It is never homogeneous, rather consisting of several voices: those of teachers and students as well as the voices of principals, parents, politicians, curriculum designers, textbook writers, publishers, inspectors, neighbours and the media (Juffermans & Van Der Aa 2013).

2. Educational discourse is fashioned by networks of policymakers, scholars, lobbies, political parties, unions and social movements (Rambla & Veger 2009).

3. In terms of scale of expansion, educational discourse is classified by global (since the end of the 20th century: common educational principles in different national contexts to provide worldwide sustainable development), regional (e.g. specific educational strategies for the countries of the north and south), national (educational traditions, principles of pedagogy), institutional (group discourse, e.g. education for disabled people), and individual (learner-centred approach) (Polunina 2011).

Inasmuch as learning is not only a cognitive concept but rather 'a type of social interaction' (Gee 2011), any discourse appears to have educational connotations. In the literature, educational and pedagogic discourse are hardly distinguished. Therefore, it is proposed that a distinction be made between educational and pedagogical discourse. As long as education is a wider notion than pedagogy (education is the way of a learning organisation; pedagogy is the discipline that studies the methods for teaching), we would define the difference between two categories as pedagogic method implementation and didactics. Pedagogic discourse is didactical, specified by teaching methodology, while educational discourse may avoid didactical norms and be presented in either pedagogic or quasi-pedagogic form.

Having considered what discourse is, how it is presented in educational practices and the particularities of educational or pedagogic discourse, we describe the discourse of MOOCs using the following seven criteria:

-

Social determinism: socially specified.

-

Area of implementation: language of science and profession.

-

Status of a transmitter: pedagogic language.

-

Rhetorical method: oratory, narratives.

-

Discourse flexibility: closed (fixed, adjusted).

-

Type of influence: descriptions of future, persuasive discourse.

-

Scale of influence: global.

Following Bernstein and Solomon's (1999) features of pedagogic discourse, online courses can be described in the following way:

-

Basic forms of pedagogic relations: tacit (change of knowledge, conduct or practice occurs, where neither of the members may be aware of it). At the same time, online discourse seems to be able to easily assume the implicit form, if educational results are being evaluated and controlled.

-

Discursive forms: horizontal (segmental pedagogic act: transmitter has the intention to change, modify, develop knowledge but does not evaluate the result).

-

Pedagogic modalities: neither official nor local (modality is still being defined, institutionalised).

Though the area of online discourse implementation is professional, the language used is not the everyday (vernacular) but rather socially specified language (non-vernacular), characterised by rhetorical expressiveness and official pedagogic modality. Online discourse is first educational, then pedagogic. It can be called quasi-pedagogic or media-discourse (Bernstein & Solomon 1999), as being performed with segmental acts. What makes online discourse closer to media style is its potential for expressiveness, containing many tools to affect emotions: music, pictures, games, bright colours (Glebova & Platonova 2016). Online discourse is discourse-text (not discourse-speech), because it is closed, fixed and pre-planned. Moreover, online discourse is image-like text (Kress & Van Leeuwen 1996) - visualisation, on the one hand, makes it expressive, attractive and captivating. On the other hand, images, as any other discursive elements, transfer meaning that is not always clearly seen behind the visual objects accompanied by sounds, words and intonations. That is why it is necessary to approach image-like texts critically and to analyse the meaning-making process they accomplish.

Approaches to reading and comprehending image-like text of online courses

The textual and visual structure of online courses is only one example of a contemporary way of meaning representation. This type of text that represents meaning by means of a mixture of different modes has been investigated by linguists, philosophers and sociologists since the 19th century, initially as a paralinguistic means of communication in writing. Since the 1870s, particular research interest has been aroused in the expressiveness of the paralinguistic means of written communication, to the question of an author's artistic design realisation (Anisimova 2003). Since the 1990s, the so-called non-verbal features of a text, which accompany verbal commutation to express distinctive connotations, have been attracting the attention of researchers. Decoding of verbal and non-verbal constituents of texts and their interpretation has found its place in linguistics, sociology and philosophy. Creolised texts, as a distinctive group of paralinguistic active texts (Anisimova 2003), are texts that consist of two inhomogeneous parts - one is verbal (relating to language, speech) and the other is non-verbal (relating to a different sign system, presented with iconic, graphic images) (Sorokin & Tarasov 1990).Thus, the formula of a creolised text might look like this: 'creolised text = text (verbal constituent) + image (non-verbal constituent)'. Taking into consideration that images, graphics and pictures tend to dominate contemporary communication, Kress and Van Leeuwen (1996) call these type of texts 'image-like texts' or 'multimodal texts'. The texts of the multimedia age present information across a variety of modes, including visual images, design elements, written language and other semiotic resources (1996). The mentioned authors appeal to visual literacy as part of the school curriculum to educate learners on how to interpret these image-text combinations, because images and texts can be combined in a unique way. To decode the meaning of such combinations, readers need 'new skills of interpretation and representation' (Serafini 2009).

Multimodal creolised text, full of images, graphics, sounds, colour combinations and so on being widely presented in newspapers, advertisements, comics, posters, Web pages and blogs, is becoming part of contemporary educational discourse. Online courses clearly exemplify the multimodality of educational discourse they apply to create and disseminate meaning (Platonova, Tarasova & Golubinskaya 2015). Because the courses are massive and free, they attract thousands of learners of different cultural backgrounds. Therefore, multimodal, especially visual, literacy is becoming crucial for those who learn from the courses.

Multimodal literacy is a set of competencies allowing effective learning in the digital environment. We derive it from the definition of multimodal literacy as an indication of a way processes of literacy - reading, writing, talking, listening and viewing - are occurring within and around new communication media (Walsh 2010). Multimodal literacy has been relevant ever since photographs, videos, sounds and other modes of knowledge representation began to receive widespread application in communication practices. There are those who create and deliver messages in the form of multimodal text and those who receive them (Mey & Dietrich 2016). Both have to be literate in the same manner to make meaning from the messages and understand each other.

Visual literacy is a part of multimodal literacy, defining the approach to the visual constituents of multimodal texts. According to the Association of College and Research Libraries (n.d.), visual literacy is a set of abilities helping one to effectively deal with images in accordance with one's needs, that is to 'find, interpret, evaluate, use, and create images and visual media'. Moreover, visual literacy enables one to comprehend 'the contextual, cultural, ethical, aesthetic, intellectual, and technical components of image-like texts. If literacies related to different modes of meaning-making such as tactile, kinaesthetic, olfactory and gustatory (Mills & Unsworth 2017) are not widely presented in research and educational practices, visual literacy is promoted to be included in school curricula (Kress 2003).

In the framework of this article we are interested in visual literacy as a learner's ability to interpret images and extract ideas from the educational visuals he or she watches. Reading images is comparable with reading verbal texts. It is possible to read on the surface level to grasp only the main idea by recognising familiar items of texts, whether it be words or images. One may read attentively to remember the text and see in which way new information may be added to existing knowledge. The deepest comprehension of the text is possible by approaching it critically. Critical thinking is especially needed when one reads a multimodal text.

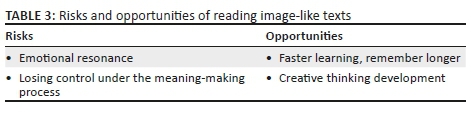

Technologically enhanced educational practices necessitate that learners get familiar with the ways knowledge is presented in order to transmit ideologies, values and beliefs to inspire the desired actions (O'Halloran, Tan & Marissa 2017; Unsworth 2006). However, living in an image-saturated culture (Kellner 2002) and with visually aggressive advertising, television and Internet, one gets used to so-called lazy looking (Emanuel & Challons-Lipton 2014). On the one hand, reading images resembles reading verbal texts. On the other hand, there are some differences in the way one makes meaning from words as opposed to images. When we read a verbal text, we commonly make meaning gradually, step by step. This way we tend to control the meaning-making process in an attempt to find how facts are interconnected. However, when we see images, we easily become overwhelmed with emotions and may simply become bombarded with several ideas appearing at once. This way we lose control and systemic understanding of the facts described, becoming captivated, moved by visual proofs that look real.

However, there are some advantages for learners when using visuals. Visualised information can help us to learn faster inasmuch as it contains several meanings which we grasp all together very quickly. According to the cognitive theory of multimedia learning, learning from words and pictures is much more productive than learning from words alone (Mayer 2009). Moreover, visual constituents of educational texts may stimulate visual thinking, which is a way to spark creativity (Grabska 2015). Risks and opportunities of reading image-like texts are presented in Table 3.

Thus, visual literacy and critical thinking are competencies of the contemporary learner, helping him or her learn from online courses in the most effective way. To critically interpret multimodal texts of online courses, one definitely has to have prior knowledge of visual grammar and the habit of thinking twice or even more times before coming to a conclusion. However, one more thing is needed: a technique - the exact way to follow when reading educational image-like texts. There are techniques for memorising, reading texts effectively, called cognitive and meta-cognitive strategies. However, these strategies and techniques are about texts in their verbal form. What we suggest for online course learners is to apply cognitive and meta-cognitive reading strategies, adapted to approach multimodal texts (Table 4).

Conclusion

Learning is not an 'innocent' process. It is a hugely complex process where, as Gadamer (1990:311) said, 'horizons melt into each other'. A lifetime of knowledge and experiences from the teacher-lecturer is bound to settle into his or her course offerings, creating light to severe influences. Likewise, the student will interact with the offered material, with the whole of his horizon of lived knowledge and experiences.

Thus far, nothing new has been said. What is important, though, is the realisation that teaching and learning is not the mere sharing and appropriation of course content. For many years content was king - but only because content was seen as manageable. Recently the realisation dawned that teaching and learning should also include the ability to master content as part and parcel of the process. The reason is clear, in that the knowledge explosion makes it impossible to teach and learn all that there is to learn. Learners should be empowered to continue on a path of lifelong learning, if teaching and learning are to be effective.

This is not enough, though. To this should be added that social and cultural horizons are equally limitless and that content is not neutral. With online course student numbers running into millions, teacher and student alike need to be aware that relevance is important and that relevance is also local. Part of the course should be devoted to helping students identify the ideological baggage of text and image and to allowing different horizons to melt into each other with the goal of making the knowledge relevant and useful in their local context. Tools to help student and teacher alike to become aware of this may include discourse analysis, as described here.

The development of these kinds of skills reflects back onto the teacher. Self-knowledge is important, and the ability to teach in such a way that the ability to identify implicit ideologies, but transcend them by making them useful, is crucial.

Only by doing this might online learning become an instrument of education and not merely indoctrination, helping to create online educated and not online indoctrinated humans.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exist.

Authors' contributions

I.P. and I.G.P.G. both contributed to the writing and editing of the document.

Ethical consideration

This article followed all ethical standards for carrying out research without direct contact with human or animal subjects.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

References

Ahmadi, M.R. & Hairul, N.I., 2012, 'Reciprocal teaching as an important factor of improving reading comprehension', Journal of Studies in Education 2(4), 153-173. https://doi.org/10.5296/jse.v2i4.2584 [ Links ]

Altbach, P.G., 2014, 'MOOCs as neocolonialism - Who controls knowledge?', International Higher Education 75, 5-7. https://doi.org/10.6017/ihe.2014.75.5426 [ Links ]

Anisimova, E.E., 2003, Лингвистикатекстаимежкультурнаякоммуникация (наматериалекреолизованныхтекстов) [Linguistics of a text and intercultural communication (based on the examples of creolized texts)], Academia, Moscow. [ Links ]

Association of College and Research Libraries, n.d., ACRL visual literacy competency standards for higher education, American Library Association (October 2011), viewed 24 June 2018, from http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/visualliteracy. [ Links ]

Bakhtin, M.M., 1981 [1935], The dialogic imagination: Four essays, University of Texas Press, Austin, TX. [ Links ]

Bernstein, B. & Solomon, J., 1999, 'Pedagogy, Identity and the Construction of a Theory of Symbolic Control': Basil Bernstein questioned by Josef Solomon, British Journal of Sociology of Education 20 (2), 265-279. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425699995443 [ Links ]

Bogutzkaya, I.N., 2009, 'Linguistic essence of class (auditorial) educational discourse', Вестник Югорского государственного университета 1(12), 45-49. [ Links ]

Bohnsack, R., 2009, Qualitative Bild- und Videointerpretation. Die dokumentarische Methode, Opladen, Budrich. [ Links ]

Breckner, R., 2010, Sozialtheorie des Bildes. Zur interpretativen Analyse von Bildern und Fotografien, transcript, Bielefeld. [ Links ]

Ebben, M. & Murphy, J.S., 2014, 'Unpacking MOOC scholarly discourse: A review of nascent MOOC scholarship', Learning, Media and Technology 39(3), 328-345. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2013.878352 [ Links ]

Emanuel, R. & Challons-Lipton, S., 2014, 'Critical thinking, critical looking: Key characteristics of an educated person', in L. Shedletsky & J. Beaudry (eds.), Cases on teaching critical thinking through visual representation strategies, IGI Global, Hershey. [ Links ]

Fairclough, N., 1995, Critical discourse analysis: The critical study of language, Longman, London. [ Links ]

Frow, J., 1980, 'Discourse genres', Journal of Literary Semantics 9(2), 73-81. [ Links ]

Foucault, M., 1981, 'The order of discourse', in R. Young (ed.), Untying the text: A post-structuralist reader, pp.48-79, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London. [ Links ]

Gadamer, H.-G., 1990, Hermeneutik I. Wahrheit und Methode. Grundzuge einer philosophischen Hermeneutik, J.C.B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck), Tübingen. [ Links ]

Gee, J.P., 2011, 'Discourse analysis: What makes it critical?', in R. Rogers (eds.), An introduction to critical discourse analysis in education, 2nd edn., pp. 23-46, Routledge, New York. [ Links ]

Giroux, H.A., 1990, 'Rethinking the boundaries of educational discourse: Modernism, postmodernism, and feminism', College Literature 17(2/3), 1-50. [ Links ]

Glebova, L.N. & Platonova, Y.A., 2016, 'Multimodal educational text of massive open online courses: Recommendations for content visualization', Научныйдиалог 10(58), 336-348. [ Links ]

Gokhale, M., 2015, 'Photographic memory technique: An effective tool for reading and memorizing in science subjects with special reference to Plant Growth and Development at under graduate level', International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Development 2(9), 521-528. [ Links ]

Gous, I.G.P., 2015, 'Learning strategies', in I. Gous & J. Roberts (eds.), Teaching life orientation (senior and FET phases), pp. 42-58, Oxford University Press, Cape Town. ISBN 9780199053643. [ Links ]

Gous, I.G.P. & Roberts, J.J., 2016, 'Learning reprioritised: Supporting the ODeL student by developing a Personal Information Management Systems and Strategies program (PIMSS)', in Forging new pathways of research and innovation in open and distance learning: Reaching from the roots. Conference Proceedings: 9th EDEN Research Workshop, Oldenburg, Germany, 4-6 October 2016. Edited by Airina Volungeviciene, András Szűcs and Ildikó Mázár on behalf of the European Distance and E-Learning Network. ISBN 978-615-5511-12-7. [ Links ]

Grabska, E.J., 2015, 'The theoretical framework for creative visual thinking', in J.H. Gero (ed.), Studying visual and spatial reasoning for design creativity, pp. 1-13, Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9297-4_3 [ Links ]

Halliday, M.A.K., 1978, Language as social semiotic, Edward Amold, London. [ Links ]

Hodge, R. & Kress, G., 1988, Social semiotics, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY. [ Links ]

Juffermans, K. & Van der Aa, J., 2013, 'Introduction to the Special Issue: Analyzing voice in educational discourses', Anthropology and Education Quarterly 44(2), 112-123. https://doi.org/10.1111/aeq.12010 [ Links ]

Kabilan, M.K., 2013, 'The importance of metacognitive reading strategy awareness in reading comprehension', English Language Teaching 6(10), 235-244. [ Links ]

Kellner, D., 2002, 'Critical perspectives on visual imagery in media and cyberculture', Journal of visual literacy 22(1), 81-90. https://doi.org/10.1080/23796529.2002.11674582 [ Links ]

Kress, G., 2003, Literacy in the new media age, Routledge, London. [ Links ]

Kress, G. & Van Leeuwen, T., 1996, Reading images. The grammar of visual design, Routledge, New York. [ Links ]

Lohfink, G., 2015, 'Struggling readers' "Noticings" to make meaning of picture books', The Open Communication Journal 9, 12-22. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874916X01509010012 [ Links ]

Mayer, R.E., 2009, Multimedia learning, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511811678 [ Links ]

Mey, G. & Dietrich, M., 2016, 'From text to image - Shaping a visual grounded theory methodology', Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung 17 (2), viewed 10 July 2018, from http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/2535. [ Links ]

Mills, K.A. & Unsworth, L., 2017, Multimodal literacy, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education, viewed n.d., from https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.232. [ Links ]

North, D., 1991, 'Institutions', The Journal of Economic Perspectives 5(1), 97-112. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.5.1.97 [ Links ]

Nyberg, D.A., 1975, The philosophy of open education, Routledge and Kegan Paul, London. [ Links ]

O'Halloran, K., Tan, S. & Marissa, K.L.E., 2017, 'Multimodal analysis for critical thinking', Learning, Media and Technology 42(2), 147-170. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2016.1101003 [ Links ]

Panofsky, E., 1972 [1955], 'Iconography and iconology: An introduction to the study of Renaissance art', in E. Panofsky (ed.), Meaning in the visual arts, pp. 26-54, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL. [ Links ]

Platonova, I., Tarasova, E. & Golubinskaya, A., 2015, 'Creolized text as a form of modern educational discourse', Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 214, 788-796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.719 [ Links ]

Polunina, L.N., 2011, 'European educational discourse: The experience of typological research', Известия Волгоградского государственного педагогического университета 6, 127-130. [ Links ]

Pressley, M., 2000, 'What should comprehension instruction be the instruction of?', in M. Kamil, P. Mosenthal, P. Pearson & R. Barr (eds.), Handbook of reading research, vol. 3, pp. 545-561, Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ. [ Links ]

Rambla, X. & Veger, A., 2009, 'Pedagogising poverty alleviation: A discourse analysis of educational and social policies in Argentina and Chile', British Journal of Sociology of Education 30(4), 463-477. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425690902954638 [ Links ]

Rautiainen, K. & Jäppinen, A., 2017, 'Visual literacy from the perspective of the VTS method', Journal of Literature and Art Studies 7(8), 1071-1082. [ Links ]

Rose, G., 2001, Visual methodologies: An introduction to the interpretation of visual materials, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA. [ Links ]

Schiro, M.S., 2013, Curriculum theory: Conflicting visions and enduring concerns, Sage, London. [ Links ]

Schmid, H., 1981, 'On the origin of ideology', Acta Sociologica 24(1/2), 57-73. https://doi.org/10.1177/000169938102400105 [ Links ]

Selwyn, N., Bulfin, S. & Pangrazio, L., 2015, 'Massive Open Online Change? Exploring the discursive construction of the "MOOC" in Newspapers', Higher Education Quarterly 69(2), 175-192. https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12061 [ Links ]

Serafini, F., 2009, 'Understanding visual images in picture books', in J. Evans (ed.), Talking beyond the page: Reading and responding to contemporary picture books, pp. 10-25, Routledge, London. [ Links ]

Sorokin, Y.A. & Tarasov, E.F., 1990, 'Креолизованные тексты и их коммуникативная функция [Creolized texts and their communicative function]', in V.F. Petrenko et al. (eds.), Оптимизация речевого воздействия [Optimization of a speech effect], pp. 180-186, Nauka, Moskva. [ Links ]

UNESCO, n.d.a, Open educational resources, viewed 24 June 2018, from http://www.unesco.org/new/en/doha/communication-information/open-educational-resources/ [ Links ]

UNESCO, n.d.b, Education for Sustainable Development, viewed 31 August 2018, from https://en.unesco.org/partnerships/partnering/education-sustainable-development. [ Links ]

Unsworth, L., 2006, 'Towards a Metalanguage for multiliteracies education: Describing the meaning-making resources of language-image interaction', English Teaching: Practice and Critique 5(1), 55-76. [ Links ]

Van Dijk, T.A., 1989, 'Structures of discourses and structures of power', Annals of the International Communication Association 12(1), 18-59. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.1989.11678711 [ Links ]

Van Dijk, T.A., 1998, Ideology: A multidisciplinary approach, SAGE, Thousand Oaks, CA. [ Links ]

Van Dijk, T.A., 1995, 'Discourse analysis as ideology analysis', in C. Schäffner & A.L. Wenden (eds.), Language and peace, pp. 17-33, Dartmouth, Aldershot, UK. [ Links ]

Walsh, M., 2010, 'Multimodal literacies: What does it mean for classroom practice?', Australian Journal of Language and Literacy 33(3), 211-239. [ Links ]

Yenawine, P., 1999, 'Theory into practice: The visual thinking strategies', Paper presented at the conference 'Aesthetic and Art Education: A Transdisciplinary Approach', September 27-29, 1999, Lisbon, Portugal. [ Links ]

Yenawine, P., 2013, Visual thinking strategies: Using art to deepen learning across school disciplines, Harvard Education Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Ignatius Gous

gousigp@unisa.ac.za

Received: 30 Nov. 2018

Accepted: 15 Jan. 2019

Published: 26 Sept. 2019

Note: OEH: The Online Educated Human: Teaching values, ethics, morals, faith and religion at a distance, sub-edited Ignatius Gous (University of South Africa).