Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

HTS Theological Studies

versión On-line ISSN 2072-8050

versión impresa ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.74 no.3 Pretoria 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v74i3.4964

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Township churches of Tshwane as potential change agents for local economic development: An empirical missiological study

Lukwikilu C. Mangayi

Department of Christian Spirituality Church History and Missiology, University of South Africa, South Africa

ABSTRACT

This article contributes towards ascertaining the potential of township churches as change agents for local economic development (LED) in Tshwane. Five church leaders (i.e. two from Soshanguve and three from Hammanskraal) were engaged through personal interviews to gain insights from them about their churches' praxes and mission orientations in relation to community building, including LED in Tshwane. Based on these personal interviews, it was established that these churches have assets as well as current ministries that could be stepping-stones for LED.

Introduction

Township churches are undoubtedly potential change agents for local economic development (LED). Hence, I argue in this article that the church can be re-positioned or rediscovered as an asset which can be used to form strong community structures in local communities, which can again be used as a basis for community development and LED. This article, based on empirical research conducted in 2015, unearths some pointers and insights that support this argument. The research involved five local church leaders.

Churches led by these pastors are located in the periphery of the City of Tshwane (CoT) which historically is a tale of two cities (the one developed and resource-rich, the other less developed and under-resourced). These leaders' congregations are found in the less developed and under-resourced townships of Soshanguve (S) and Hammanskraal (H) in the northern regions of the CoT. Three of these churches are 'daughter' churches, meaning they are the historical products of mainline, colonial missionary churches. These are Uniting Reformed Church in South Africa (URCSA), Evangelical Lutheran Church in South Africa (ELCSA) and Letlhabile Baptist Church, while the other two are independent African initiated, of a Charismatic/Pentecostal type.

Churches on the peripheral, struggling urban areas of the CoT experience the economic imbalances in various negative ways. I firstly observed that many churches planted in these struggling urban areas do not attain financial sustainability. Secondly, I have also observed that with the exception of a few, most of these churches' members are poor and unemployed, so that their numerical growth does not translate into financial viability, resulting in ultimately being dependent on outside assistance for their survival. Thirdly, I have also observed that these churches can achieve self-governing status and some degree of self-propagation but are hardly self-sustaining. Lastly, as South Africans, much like other Africans, are migrating to the city at an increasing rate, it is most likely that churches in peripheral urban areas are growing rapidly in numbers (see Mangayi 2016:8). 'These churches will require economic engines to sustain them' (Mangayi 2016:8) and the communities they serve. It is therefore crucial that they should contribute towards nurturing LED in their communities. Further, I contend that the praxes and mission orientations of these churches have an inescapable responsibility to contribute towards collective well-being, including LED in their townships.

Hence, the main question of this research: What insights could be gained from church leaders' views/interpretations of their churches' praxis matrixes and mission orientations, which could make the township churches of Tshwane into change agents for LED? Answers to this question are provided in the findings section of this article as well as in literature.

A brief word on churches in Tshwane

Historically, Protestant churches from Europe, including the Dutch Reformed Church, rode on structural changes in the South African society and industrial capitalism. They aligned themselves to the industrial capitalist imperatives and ended up serving white-controlled interests in all sectors of society. These churches failed in those years (and still do) to develop an authentic mission agenda geared towards economic liberation and transformation (Mangayi 2016:239). This legacy is still present in many of the Protestant churches operating in the CoT (S and H). This disposition is detrimental to their involvement in LED in Tshwane (S and H). The ecclesiastical formations that participated in this research still bear the legacy of an unjust class system. Churches in the suburbia of Tshwane that benefited from historically unjust socio-economic and political systems are wealthy and in a comfort zone, while those in townships, with Africans in the majority, still struggle to survive. These churches in the townships minister to people in the margins and lack the financial resources to sustain their work.

Contemporary features of South African townships

The following features of townships and marginalised communities in South Africa and other parts of the world are also prevalent in Tshwane:

-

Township communities and marginalised neighbourhoods lagging behind the nation in employment generation patterns (Blakely 1994:19; Conn & Ortiz 2001:69).

-

Neighbourhood and community decline: economic restructuring resulting in very uneven spatial influences both nationally and within communities. The root cause of this problem is systematic disinvestment in these areas (Blakely 1994:20). This is not a new situation in S & H, but now it is worse because since 1994 there has hardly been any investment.

-

The absence of local markets meant not only lost services but also lost income (Blakely 1994:24).

-

The rising underclass associated with teenage pregnancy results in high dropout rates in schools, as well as family breakdown. All these factors prevent this underclass from realising upward economic mobility. Women form the bulk of the new underclass for many reasons, including female-headed households operating below the poverty line (the feminisation of poverty). It has been pointed out that 'female poverty has been the most striking feature of the social welfare system (…) these women cannot find a way out for themselves or their offspring' (Blakely 1994:25).

-

Under-education and illiteracy are also central features of the so-called underclass.

These features should not be ignored by the church on mission with God.

Mission, church and local economic development

I view mission as Hoekendijk (1966:105) defined it: as God's activity through the church for the establishment of his kingdom and the total salvation of humanity. It concerns participation in the movement of God's love towards the people, as God is a fountain of sending love (Bosch 1991:390; Musasiwa 1996:195). The ultimate aim of mission is the glory and manifestation of God's grace (Voetius 1643 in Kritzinger, Meiring & Saayman 1994:1). Mission is thus regarded as a movement from God to the world and the church is viewed as an instrument for that mission (Bosch 1991:390). This implies that the scope of the church's mission is more comprehensive than has traditionally been the case:

Local economic development fits reasonably within such an understanding of mission, because the aim (that is, to build a self-sustaining LED for the common good) resonates with the love at the heart of the missionary God in economic and social terms. (Mangayi 2016:24)

Our participation in the movement of God's love towards the world includes an evangelistic as well as a socio-economic responsibility (Bosch 1991:405; Steward 1994:22; Stott 1975:23). 'Such an understanding of mission embodies in word and deed that Christ died and rose from the dead, that he lives to transform human lives and to overcome death' (Mangayi 2016:24).

To this effect, the church should find its identity in its close interaction with the world. In his Letters and Papers from Prison, Bonhoeffer (1971:382f) wrote: 'The church is the church only when it exists for others … The church must share in secular problems of ordinary human life, not dominating, but helping and serving'.

Agreeably, Bosch (1991:368-389) suggested that we become 'the church-with-others' as this enhances the possibility of authentic coexistence. This church-with-others is a substantial instrument for God's mission to the world. Its role towards LED will be inspired by its commitment to comprehensive or holistic mission. This church has to recognise that it cannot exist outside of its relationship with the world. What is required in our time is 'a dynamic, purposeful, world-directed ecclesiology' (Van Engen 1991:160).

The conceptualised church that I have suggested here 'will not only be oriented towards the world, but will also seek to position itself on the margins of society to hear the suppressed voices of the poor and unemployed' (Mangayi 2016:25). It will promote 'the welfare of humanity but also the greater world community and will function in a holistic and integrated, incarnational, intentional, contextual, empowering and sustainable manner' (Mangayi 2016:25).

Empirical work: Research methods

Participants' profile

Interviewees included Rev. Aristorica Phiri (Hammanskraal Gospel Centre), Rev. Christian Rustof (Letlhabile Baptist Church), Pastor Stanley Mokone (Youth pastor at Lutheran Church Soshanguve Block L), Rev. Maponya (Uniting Reformed Church of South Africa/Soshanguve) and Pastor John Megala (Body of Christ Ministry/Lepengville-Hammanskraal). With the exception of Pastor Megala (who has attained general education up to grade 12), three Reverends (Phiri, Rustof and Maponya) have received formal theological education, the minimum being three years post-secondary education. Pastor Mokone is a student pastor and youth worker with secondary education plus two years of theological training.

Personal interviews with these church leaders were conducted on respective church premises on 04 May 2015 with Revs Phiri, Rustof and Pastor Mokone, on 05 May with Pastor Megala and on 17 November 2015 with Rev Maponya. Their views are summarised as presented in the section on findings.

Data collection

In order to gather information related to these churches' mission orientations and praxes, I used a praxis matrix grid provided by Kritzinger (2008) with questions pertaining to agency, contextual understanding, ecclesial scrutiny, interpreting the tradition, discernment for action, reflexivity and spirituality. I used the same guiding questions as those developed by Kritzinger (2008) for interviews with church leaders. Findings of these interviews are presented later in this text. However, what I report later in the text are impressions of the five church leaders who participated in these interviews; I acknowledge that this small number places severe limitations on making valid observations and deductions. Nevertheless, I gained certain ideas from these interviews, which enhanced my understanding about the orientations and praxes of these churches in relation to LED.

The praxis matrix grid was also used to critique, examine and present what these congregations are doing as far as mission is concerned on the ground. The grid includes the following categories with specific questions under each category:

-

Agency: What are the power relations prevailing between them? How do these factors influence their approach? Who are their 'interlocutors', who help 'set their agenda' and determine their priorities? How do all these factors shape their approach?

-

Contextual understanding: What are the social, political, economic and cultural factors that influence the society within which they are working and witnessing? How do the change agents analyse that specific context? How do they 'read the signs of the times?' How do these factors shape their approach?

-

Ecclesial scrutiny: What were the practices of churches and Christians in the past in that particular community? Did it give the church(es) a good or a bad name in the community? Do churches have positions of power and privilege or influential public contacts? What are the physical and institutional structures of the churches and how are they utilised in or for the community at large? What are their leadership patterns and structures? How do these factors shape their approach?

-

Interpreting the tradition: How do the change agents (re)interpret the Bible and their theological tradition in the light of the questions raised by the previous three dimensions? Is there a unique formulation of the Christian message that is arising in this context? How do these theological insights shape their approach?

-

Discernment for action: What kind of concrete faith projects or organisations are they involved in, particularly in relation to the community at large? What kind of plans are they making to embody their theological insights in the community? How broad is the theological agenda and how does it actually shape their actions?

-

Reflexivity: Do the change agents consistently and honestly reflect on the impact and results of their work in the community? Do they learn from their experiences? How does this shape their approach in the community? Does this reflection lead to renewed and deepened agency, contextual understanding, interpretation of the tradition, spirituality and planning?

-

Spirituality: What type(s) of spirituality is/are practised by the change agents? What is the dominant spirituality among them? Is this a source of inspiration and encouragement to the group? How do these factors of spirituality shape their approach (in relation to LED)?

Then I used insights presented by Roozen, McKinney and Carroll (1984:87) about the four different 'mission orientations' that a religious community could have in society to further analyse these congregations as you will see later.

Contextual backgrounds of participants' churches: Snippets

Uniting Reformed Church in South Africa - Soshanguve congregation

This congregation of the Uniting Reformed Church, situated at 1107 Block H in Soshanguve, is a missionary church. The URCSA came into being on 14 April 1994 from two of the four members of the Dutch Reformed Church Family of Churches (i.e. the Dutch Reformed Church in Africa [DRCA] and the Dutch Reformed Mission Church [DRMC]). In terms of skin colour, the union of the black and coloured churches formed the URCSA.

Most of its congregations, including Soshanguve, comprise previously disadvantaged groups who are still suffering from the legacy of apartheid. Also, in comparison with its mother denomination, URCSA evidences many weaknesses and has very limited resources for ministry. Chief among these include limited physical structures (buildings), inadequate finances, weak administration, inadequate networks, a shortage of ministers, vacant congregations, insufficient formation centres, inadequate responsible stewardship, weak prophetic (advocacy) voices, staff shortages, inadequate focus on youth, inability to utilise the expertise of members and inadequate guiding of a variety of spirituality (see Minutes of the Sixth General Synod of URCSA 2012:14-15).

In Soshanguve, for example, there is very limited building infrastructure on site such as dedicated classrooms for Christian instruction. The main meeting venue (the sanctuary) is inadequate to accommodate concurrent meetings when needed. This has negative implications for ministries to different church members. This also means that it is difficult for this congregation to make its facility available to strategic community ministries such as skills development training centres and youth community development which is much needed in the area for the purpose of LED. This situation also means that the congregation is unable to render service and witness to weak and vulnerable members of the church and community in meaningful ways.

Regardless of these challenges, the congregation has structured its ministries along the Integrated Ministry Model as it seeks to reach out and minister to its members and to the community at large.

Evangelical Lutheran Church - Soshanguve

The Evangelical Lutheran Church situated on 1250 Block H in Soshanguve is a missionary church, its historical background being linked to Lutheranism in South Africa. Garaba and Zarvedinos (2014:5) write that Lutheranism in South Africa developed from two main sources. Firstly, from the work of Lutheran missionaries that ultimately led to the establishment of indigenous Lutheran churches and, secondly, from Lutheran settler congregations of German and Scandinavian background that also evolved into independent Lutheran churches (cf. Wittenberg cited in Garaba & Zarvedinos; Florin 1967:93).

Evangelistic outreaches by missionaries led to the establishment of a number of indigenous churches, one of which is the ELCSA to which the Soshanguve congregation belongs.

Letlhabile Baptist Church - Refentse/Hammanskraal

Letlhabile Baptist church is situated in Refentse (formerly Stinkwater) in Hammanskraal, stand number 958 Mokone Block. This local congregation has been a member of the Baptist Union of South Africa (BUSA) and the Baptist Northern Association since 1999. Baptists came to South Africa with the 1820 Settlers; the first Baptist church was established in the Salem/Kariega area near Grahamstown. German settlers arriving about 1859 also included a few Baptists and soon there was a flourishing German Baptist church in the area between Stutterheim and Berlin in the Eastern Cape. German and English Baptists combined to form the Baptist Union (BU) in 18771

According to Chris Parnell (1995), the spade work for what is now known as Letlhabile Baptist Church was carried out in the 1980s, when the heart of a Scottish Baptist doctor (i.e. Dr Harrower) at Jubilee Hospital was touched by the need of these people who seemed to be the most deprived and overlooked community in the whole area of Stinkwater in Hammanskraal. The people of Pretoria Central Baptist Church were also moved, and founded the Stinkwater Mission. They sorted logistical issues at the school, provided accommodation and help for a clinic from Jubilee Hospital; sank boreholes; erected buildings; started teaching vegetable, hen and egg production, sewing and knitting; and they preached Christ. They made up monthly parcels of food for elderly people and ran a soup kitchen.

From 1992 to 2002, Stinkwater Mission grew into an established Baptist church, known as Letlhabile, boasting a multi-faceted community development centre to serve the local community and Hammanskraal at large. From 2003, Letlhabile's community ministry was re-shaped to focus on issues related to orphans and vulnerable children.

Hammanskraal Gospel Centre - Kanana/Hammanskraal

Hammanskraal Gospel Centre, situated about 43 km to the north of Pretoria, is what one would refer to as a Charismatic fellowship. It is presently being pastored by Reverend Aristarico Phiri, a Zambian, and two eldership couples: Mr and Mrs S. Mkandla and Drs Peter and Carol Bombal.

The history of the church goes back to the 1980s when the fellowship used to be a Methodist church; later it became an Assemblies of God Church, which must have been in the early 1990s. In 1995, the present pastor, Rev. Aristarico Phiri, arrived from Zambia on a personal mission. Unbeknown to Pastor Phiri, God had planned already that his visit would end up in a pastoral appointment to the then small gathering of the saints (approximately 13 people) that were at the time meeting at the Youth with a Mission (YWAM) base in Renstown in Hammanskraal.

As soon as Pastor Phiri took over the pastorate of the church from Mr Edmund Pohl, the church began to pick up growth as it attracted more black people from the surrounding community of Mandela Village, Renstown and Temba. By 1996, the church was already looking for ways to extend and expand its meeting place. The YWAM classrooms were no longer enough to contain their numbers. Hence, the pastor searched for a tent. He found two tents 10 m × 5 m each, and joined them together so that they at least had a bigger room for the people who were coming. This seemed to suffice until their Sunday school started to 'burst at the seams'. The facilities at the nursery school were made available to the church to use. The latter began to flourish at that time. In 1997, it joined the Church of the Nations (COTN). It was in the same year that the hired tents proved inadequate again; one COTN church gave them a much bigger tent, 20 m × 10 m. The church continued to experience growth and numbers grew to 350 adults, not counting children. Then, they acquired a bigger piece of land at Kanana.

Their vision is to use the premises to provide for the needs of the community, such as a Christian school, a trauma counselling centre, a skills development centre for young people and possibly a refuge for homeless children. In preparation for the future, the leadership has currently embarked on a training programme for leaders through establishment of an 'In-House Bible School'.

The Body of Christ Ministry - Lepengville/Hammanskraal

The Body of Christ Ministry was founded in 1990 and is led by its founder, Pastor John Megala. The church is located at 492 Block DD Lepengville in Hammanskraal. The founder is a bi-vocational minister with basic theological training. During the day he works for Tshwane municipality in region 2 in the maintenance department. The ministry of this church is fourfold: fellowship, equipping the saints, Bible School for lay leaders and care for the aged. The mission of this church is building the Body of Christ for service. This group of believers is an African Initiated Church, in that it is born out of the vision and effort of an African leader with no ties to mainline church mission agencies. It is a Bible believing church, Charismatic/Pentecostal in its outlook and practices.

Findings: Synthesis of the church leaders' views on praxis matrixes of their churches

A synthesis of the church leaders' views on praxis matrixes of these churches to the questions of the praxis matrix reveals the following:

1. With regard to agency, it emerged that power relations in these churches are hierarchical, with considerable power being in the hands of top governance structures (such as the parish council, pastor and elders, founder and church council). The interlocutors of these churches are first their own members (ministry leaders and congregants) and then the community. The power relations and interlocutors have influenced the approach of these churches to adopt, for example, an Integrated Ministry Model in the case of URCSA Soshanguve. 'Preaching to affect lives' in the case of ELCSA Soshanguve. 'Focus on spiritual formation' at Letlhabile Baptist. 'Friendship with community and Luke 4:18-19' as a framework for Hammanskraal Gospel Centre and fostering an ongoing dialogue with community and church members in the case of the Body of Christ Ministry.

2. These churches can 'read' contextual issues as they experience them in their areas. They mentioned crime associated with poverty (as expressed by three churches), social ills (as expressed by two churches), poor health, unemployment (as expressed by three churches), vulnerability of at-risk individuals such as children and old people (as expressed by two churches), instability associated with community in transition, and old women burdened with child care. According to these churches, it is clear that unemployment and crime associated with poverty are the most pressing issues in Hammanskraal and Soshanguve. These are followed by social ills and the vulnerability of at-risk individuals. Generally, the praxis matrixes reveal that change agents from these churches analyse these issues in their interaction, through dialogue, with communities as they try to build relationships with the community at large. These issues are shaping the approach of these churches, among others, to formulate a collective vision for action (as expressed by two churches), preach Christ's love and highlight that salvation has holistic implications (as expressed by two churches), and the 'conscientisation' of the church and community about their needs and outreach through children's ministry.

3. With reference to ecclesial scrutiny, the praxis matrixes show:

a. some churches did relief and community development (as expressed by three church leaders)

b. it was acknowledged that in the past these churches were mostly silent and stood at a distance from community issues (as expressed by two churches), only paying lip-service to these issues

c. through their members, these churches have influential public contacts and have good rapport with government officials

d. all these churches have building facilities of some sort which are made available to community ministry

e. institutionally, they are structured and registered with government as non-profit organisations (as expressed by four churches) and public benefit organisation (as expressed by one church)

f. the leadership patterns of these churches include the parish model (as expressed by two churches), congregational model (expressed by one church) and the neo-Pentecostal model consisting of a founder/visionary surrounded by a few elders (as expressed by two churches)

g. the following factors shaped the approach of these churches in various ways: pastoral and leadership teams guide and provide oversight and vision for community ministry (as expressed by all the churches), preaching to enhance spiritual formation and to ignite community transformation (as expressed by three churches). All these church leaders expressed that a holistic and integrated approach is preferable.

1. Church leaders' views on the praxis matrixes about interpreting tradition hint at a number of issues:

a. Change agents attempt to read the Bible and re-emphasise biblical teachings in relation to concrete needs in the community for the purpose of presenting a 'holistic gospel' (as expressed by three churches) and emphasis on building theological and biblical foundations through sound doctrines with the hope that community transformation will ensue from these teachings (as expressed by two churches).

b. Although these churches did not exhibit unique interpretation of the Bible as related to their contexts, they assert that biblical insights help them to address community issues which aim at enhancing humanity holistically (as expressed by three churches); also, sound Bible-based teaching will lead to spiritual formation which will eventually lead to community transformation (as expressed by two churches).

c. Theological insights which are shaping the approach of these churches include integrated and holistic framework for ministry (as expressed by three churches), preaching and teaching for transformation (as expressed by two churches) and the Book of Nehemiah as a framework for reconstruction and transformation (as expressed by one church).

2. Based on the views of these church leaders in relation to faith projects, the praxis matrixes show that these churches are involved in their respective areas through providing food parcels (as expressed by two churches); collaborating with local civic organisations, adopting communities in need such as orphans, refugees and elderly people (as expressed by two churches); providing psychosocial and spiritual support to vulnerable communities (as expressed by three churches); providing ministry to children at-risk (as expressed by one church); empowering through education (as expressed by two churches); facilitating income-generating projects (expressed by two churches); and participating in an ecumenical cooperation for economic development (as expressed by one church). Based on the views of the church leaders, the praxis matrixes also show that these churches plan to be consistent in presenting the gospel in an integrated holistic manner in their contexts through practical community projects. Although they are not involved in big-scale holistic faith projects, these churches visualise community service as an ongoing witness, which could open up possibilities for collective vision and ecumenical cooperation (as expressed by three churches).

3. Further, based on the views of the church leaders, the praxis matrixes show that these churches reflect on the impacts and results of their ministries in communities on a regular basis and that their leaders mainly perform these activities individually or collectively. Lessons learnt through these reflections have given them insights to correct mistakes and highlight new opportunities and challenges (as expressed by three churches) and overcome individualistic tendencies (as expressed by two churches). These reflections shape the approach of these churches in terms of seeking to be relevant to communities (as expressed by three churches) and explore new things (as expressed by two churches). The impact of reflections on praxis meant that ministry strategies are informed by the lessons learnt (as expressed by three churches) and that the context has to be considered seriously (as expressed by two churches).

4. Finally, based on the views of the church leaders, the praxis matrixes reveal that these churches aspire to practise an integrated holistic spirituality, which allows for a concomitant expression of word and deed as lived out in the community. Yet, the dominant spirituality among them and their agents of change still leans more on the word and less on involvement in community issues. Nevertheless, they found inspiration and encouragement from their ministries that seek to form bridges through community services. Although they are slow to opt for concrete spirituality, they believe that focussing on the word of God is at the core of spirituality; it will yield to forms of spirituality that will influence communities for the better and foster ethical behaviours.

In relation to LED, the views expressed by church leaders on the praxis matrixes of these churches confirm that the church has crucial assets and is a crucial asset in townships and as change agents should develop a public theology for LED. These peripheral churches possess important assets such as physical and institutional structures, spiritual and moral foundations, and access to deprived grassroots at-risk communities, contacts with public offices, cross-cultural relationships and predisposition to care for the poor. These assets can be further mobilised to generate vision, motivation and responsibility for a public theology in such a way that township churches become visible strategic participants in LED in Tshwane, even though they might have some weaknesses in their mission orientations.

Participant church leaders' insights on their churches' mission orientations

Having presented and described the churches that participated in this research according to the views of church leaders using Kritzinger's praxis matrix in the previous section, I undertook an analysis of their strengths, weaknesses and blind spots to establish their mission orientations. The insights presented by Roozen et al. (1984:87) about the four different 'mission orientations' that a religious community could have in society are used to further analyse these congregations. Kritzinger (2013) elaborates:

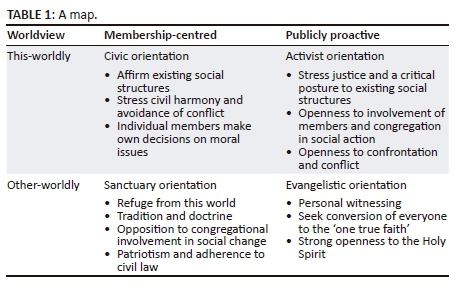

They (i.e. Roozen, McKinney and Caroll) look at how the worldview of a community (the question whether it is this-worldly or other-worldly in orientation) combines with the boundary-making activities of that community (the question whether they are membership-centred or publicly proactive) to produce four mission orientations, which they call a civic, sanctuary, activist and evangelistic orientation. (p. 37)

I applied these insights to help me establish whether the mission orientations of these churches would be suitable for LED or not. The four mission orientations are described in Table 1.

Boundary making

Each church was scrutinised using these four mission orientations. Thereafter, the strengths, weaknesses and blind spots of these churches will be discussed in relation to them being change agents for LED.

Based on the praxis matrix of the URCSA Soshanguve described by the church leader, we could establish that this church's focus is on one hand this-worldly in that it interacts with the community on an ongoing basis. To some extent, its mission focus includes both elements of being member-centred (i.e. it encourages members to do community outreach which hints at civic orientation) and publicly proactive in that, through its Integrated Ministry Model, it stresses justice and openness to involvement of its members in faith projects which suggests activist orientation. On the other hand, in the mix of these two focusses (members-centred and publicly proactive), this church also has an other-worldly perspective through its evangelistic orientation as it carries out Christian education and evangelism in the community.

From the praxis of the ELCSA Soshanguve church described by the church leader, we could establish that this church's focus has elements of both this-worldly and other-worldly perspectives. In relation to a this-worldly perspective, its members are expected to live as Christian witnesses in the community on moral issues and affirm social structures such as civic associations in its civic orientation. In its activist orientation, this church, through its diaconate ministry, is openly involved in social action such as adopting communities in need and providing psychosocial and spiritual support. In relation to an other-worldly perspective and with reference to its evangelistic orientation, this church attempts to present the gospel of Jesus for salvation.

Based on the current praxis matrix of Letlhabile Baptist church described by the leader, we could establish that this church's focus combines elements of this-worldly as well as other-worldly perspectives. In relation to the former perspective, through spiritual formation based on a theological and biblical foundation in the word, this church expects its members to make decisions on moral issues by being informed by the Bible and to affirm existing social structures in its civic orientation. In its activist orientation, this church is involved in addressing challenges faced by children and the burden of old women in relation to childcare. With reference to an other-worldly perspective, this church emphasises children's evangelistic outreaches in primary schools of the community as part of its evangelistic orientation.

From the Hammanskraal Gospel Centre's praxis matrix, we could establish that this church's focus is also a combination of this-worldly as well as other-worldly perspectives. In relation to the first perspective and within its civic orientation, this church affirms existing social structures such as other non-profit organisations, while through its in-house Bible School it focusses on character formation and training of Christian leaders of the area so that they make their own decisions on moral and social issues. With reference to its activist orientation, this church assesses and 'studies' community needs in order to influence a practical vision for transformation in the area. In relation to an other-worldly perspective, this church has an openness to the Holy Spirit and emphasises evangelistic outreaches as one of the goals of its in-house Bible School.

Finally, the Body of Christ's praxis matrix described by the church leader portrays that this church, although it proclaims the Bible, leans more towards a this-worldly perspective. In this regard, this church has both civic and activist orientations. With regard to civic orientation, this church's members are expected to live out as Christians among the people of the community in practical ways as models for ethical behaviours. In relation to activist orientation, this church is involved in an income-generating project for the elderly and is also participating in a local ecumenical cooperation for economic development. Its activist orientation is inspired by the Book of Nehemiah, which leaders have adopted as a framework for socio-economic and spiritual reconstruction and transformation.

From the foregoing, it is clear that most of these churches, as described by church leaders, evidence both this-worldly and other-worldly perspectives of mission. In essence, they are witnesses for Christ in this world while they also point to the world to come. All these churches contain elements of civic orientation of mission in them, especially in relation to expectations that their members will live in communities as moral and ethical individuals. All these churches also display elements of activist orientation of mission as all of them are involved in various faith projects, albeit small initiatives, in their communities. Four of the five churches exhibit elements of evangelistic orientation of mission in terms of evangelistic outreaches aimed at conversion. Together, the mission orientations of these churches, as described by the church leaders, confirmed that these churches already possess certain assets which could prove to be building blocks for LED. These include their apparent activist orientation manifested in the faith projects in which they are currently engaged. Some elements, such as cooperation and affirmation of social structures in the civic orientation of these churches, could also prove to be assets for building sustainable societies that uphold God's economy and rules, the oikos.

I would argue that all four elements (the this-worldly and other-worldly worldview and activist and civic orientations) of the congregations could contribute to upholding the household of God's economic rules for a healthy spiritual-psychological-community activist organism to exist in the social ecology of society. All these would be necessary, and in a very special way the spiritual, other-worldly aspects, which are the 'life' and 'breath' of a faith organisation in this world, do function more on the interaction of these elements in establishing the oikos. Generally, the practical expression of these local churches combines both the facilitation of a person's connection with God's resources for spiritual and eternal life and an expression in the social realm, mainly through community projects. This is good for a starting point but not enough to bring about LED, which is sustainable and equitable in the CoT (S & H). Nonetheless, they need to build on this by intentionally becoming activists for the collective well-being of S and H, as well as the rest of the Earth. The contributions of these congregations towards LED in Tshwane (S & H) should lead communities 'to go back to respecting and living with the earth, in order to find long term solutions' (Van Schalkwyk 2008:10) to the socio-economic deprivations these communities currently face.

Discussion and evaluation

In this section, I evaluate the strengths, weaknesses and blind spots of these churches' mission orientations in relation to LED. Before proceeding, I reiterate that I based my observations and comments on the views of the church leaders who participated in this research and on the historical information about these churches.

Strengths

Generally, I acknowledge that events occurring after 1994 have paved the way for multidimensional reconciliation and healing in the country, including LED as a sector. Yet, as could be noticed in the praxis matrixes of these churches, they have not advanced any significant reconciliation and healing cause. The selective elements of mission orientations point to this fact as discussed later. The fact that these churches have taken first steps in their activist orientations should be seen as a strength, and the physical and human assets dedicated to this activism should be added here. Future efforts could be built upon these first steps in faith projects. The rich heritage of the church's involvement in social activism in this country and the world over is also a strength which could inspire these churches, especially the missionary initiated churches, to draw from their 'own wells'.

These churches boast assets that constitute valuable strengths, such as spiritual and moral foundations, access to the most deprived grassroots communities in Tshwane (S & H), members in government and cross-cultural relationships (Nu˝rnberger 1999). They also possess physical facilities such as pieces of land and building facilities, which are crucial for LED, in addition to being located in areas with an impoverished physical infrastructure (roads, access to water, electricity and public facilities such as schools, clinics and community halls) (see Mangayi 2016:190, 194). Unfortunately, these churches still have to devise ways of maximising these assets for LED in Tshwane (S & H). The strengths of these churches must also be used in ways which respect the integrity of creation, the 'whole household of God' (Mangayi 2016:149). With the integrity of creation in mind, these strengths should enable the churches to engage in 'hopeful actions' which are 'liberating' (Mangayi 2016:169).

Weaknesses

Generally, the fragmentation of the church in the CoT (S& H) is a major weakness, rendering it very difficult to carry out collective action. Although post 1994 we have witnessed reconciliation of many denominations that used to be divided on racial lines, it is premature to conclude that the fragmentation of the church in South Africa in general and in Tshwane in particular is reversed (Roy 2000:200-201). Nevertheless, the fragmentation of the church in South Africa is further manifested in the number of new and separate church denominations that have surfaced post 1994, especially those being initiated by African leaders who have no affiliation with mainline churches.

This fragmentation of the Body of Christ is a vivid reality in townships of S and H and represents a significant weakness. Two of the research participating churches have no formal links with established denominations, while the other three are daughter churches of the so-called mainline churches, that is, the Soshanguve Uniting Reformed Church, the Soshanguve Evangelical Lutheran Church and the Letlhabile Baptist Church, yet they enjoy little meaningful fellowship with their resource-rich mother churches. Here, I refer to the type of multidimensional fellowship that builds the capacity of daughter churches in addressing issues of their context, such as LED. The church has failed, as Latini (2011:75) put it, to be a multidimensional Koinonia 2 (koinonia relationships denote that God, the church and the world all live and move and have their being in a series of constructive relationships), which constitutes a major weakness. The multidimensional koinonia is also essential for the household of God (oikos) which thrives where recognition and restoration of relations between human and nonhuman inhabitants of the planet exist. In other words, the household of God requires that there is multidimensional koinonia. If there were such a koinonia, for example, resources of wealthy Baptist, Lutheran and Reformed churches in the suburbs of the CoT could be available to these churches in the townships for LED initiatives aimed at creating employment and self-reliance. Instead, these churches in suburbia, if involved in community development initiatives of township churches at all, tend to promote relief and charity as used to be the case with Letlhabile Baptist in the 1990s. Consequently, informal and formal processes for community development spend their energies superficially on symptoms, while root causes of economic inequalities that breed poverty, unemployment and injustice remain unaddressed. Expending energy and resources on symptoms constitutes an overriding weakness for the churches that participated in this research, as indicated in their praxis matrixes.

While it is good to provide childcare relief for elderly people at Refentse as is the case with Letlhabile Baptist, the systemic economic issues that force young parents to leave their children to be raised by grandparents remain unchallenged, and will continue for generations to come. It is worthwhile to have an income-generating project as in the case of the Body of Christ Ministry in Lepengville, but as long as issues pertaining to the promotion of local goods are not addressed, this initiative will be under constant threat. Adopting of at-risk communities such as orphans and the aged as in the case of the Lutheran Church in Soshanguve is important, but this initiative would be strengthened should socio-economic and political issues that breed vulnerability, marginalisation and exclusion also be addressed. In short, focussing solely on relief and charity is a weakness for these churches located in a context of need in the CoT (S & H).

In relation to these participating churches, I deduce that the church has failed to be the embodiment of multidimensional Koinonia because she endeavours internally to do pastoral care, Christian education, worship and stewardship, while neglecting her 'ultimate outward purpose which is to be on mission with God to the world' (cf. Bosch 1991). The 'local church is - or ought to be - a family, a local expression of the worldwide family of God, whose members regard, love, and treat one another as brothers and sisters' (Stott 2003:82). I argue therefore that by its very nature, the church is born, lives and ministers in the spirit of koinonia.

Pieterse's distinctions of the church as an organism and the church as an organisation (Pieterse 1993:158) discussed earlier are helpful in clarifying the different functions of the church on mission with God, that is, pastoral and social functions. The former helps the church to be in fellowship with God and its members, while the latter aids the church to be in fellowship with the world. The social functions are important to facilitate the necessary impact of the pastoral functions. These two sets of functions are integrally related to each other. My evaluation of these churches' functions reveals an imbalance in that they attach more weight to pastoral ones and less to social functions. This is a significant blind spot, which has to be addressed so that these township churches can become assets of substance for LED in Tshwane (S & H).

Blind spots

This section points out certain blind spots, in other words subjects, about which these churches seem to be ignorant or biased. These include, among others, majoring on member-centred pastoral functions, the church being a divided church, a lack of synergy between the clergy and laity, a mismatch between programmes and resources and the local context not being taken seriously.

Focus only on member-centred pastoral functions

I observed that these churches are more comfortable with pastoral functions, which benefit their congregants but cannot position themselves to shepherd entire communities where they are located. This is so because they seem to be weak in integrating the pastoral as well as social functions. As a result, these churches are unable to live in fellowship and solidarity with the poor, regardless of the fact that they are located amidst the poor. Consequently, (1) the image and identity of the church is blurred and perceived as a self-centred institution, and (2) her assets as named earlier do not serve to transform and liberate society. In relation to the struggling parts of Tshwane, such as Pretoria Central and the townships, Rabe and Lombaard are accurate in their remarks [that] 'the needs in poor communities demand attention from religious sources, in fact overwhelming the resources available to clergy' (Rabe & Lombaard 2012:242). With particular reference to churches in S and H, the reality captured by Rabe and Lombard calls for multidimensional koinonia where sharing of resources takes place for the collective good of communities, which is currently lacking.

On one hand, the oikos concept is helpful in addressing this shortage on the part of the church and clergy in Tshwane in particular, whereas on the other it reinforces the notion of multidimensional Koinoinia. The oikos views every sector of society as interrelated in God's economy. Thus, 'the rules that God has established for our household, the world in which people live, work, struggle, flourish and die' ( The Oikos Study Group 2006:24) should be the rules of ministry in order for the church to fulfil both her pastoral and social functions.

A divided church

A divided church is both a weakness and a blind spot; the fragmentation of the church into class lends itself to the church in the centre having little concern for the church on the periphery and vice versa.

The class system is apparent for instance in the way that two congregations of the same church community choose to carry out both pastoral and social functions among people on the margins of the city, for example. This, I argue, emanates from the manner in which one church perceives the reality of society in terms of the class strata it belongs to. For example, I have seen churches from poverty-stricken areas such as townships being keener to initiate self-help projects - small community projects geared to meeting immediate basic needs - for survival. Their counterparts in the suburbia, if they wish to address issues of poverty, opt to do so in an environment where risk is substantially reduced and through partnerships with resourceful entities. It is clear that township churches are associated with lower socio-economic sectors of the population whose main preoccupation is survival to meet basic needs. The suburban churches are associated with higher socio-economic sectors of the population whose emphasis is on strategic partnerships.

The oikos concept is also helpful here in that it perceives the whole household of God as one: all the inhabitants of this household are in an interdependent relationship for survival and prosperity. Division in the church must be addressed by fostering this notion of interdependence as in the oikos.

Lack of synergy between the clergy and laity

As could be observed in the praxis matrixes of three participant churches (i.e. Letlhabile, Hammanskraal Gospel Centre and the Body of Christ), as described by the church leaders, directives and initiatives for eventual community ministry come from the elders and clergy in a somewhat disjointed manner. The clergy has the say, which drives the process as its members claim to speak on behalf of their congregations. The laity is expected to implement initiatives of which they were not part, from conception. This lack of cooperation results in a poor prognosis for an eventual community ministry. The fact that these churches continue to hold on to the concept of clergy versus laity as far as ministry in the community is concerned constitutes a significant blind spot. This further plays itself out in visualising some ministries such as preaching and teaching the gospel, undertaken by the clergy, as sacred and diaconal ministries, but when performed by the laity, as non-sacred. Worse still, clergy ministries are allocated a budget, while the diakonia ministries have to do with donations.

Here again we could learn from the household rules of God where all inhabitants contribute to the livelihood of the whole creation in harmony with the rest of the inhabitants: '… no one field of expertise or effort, let alone any person or group of people, has the preeminent or only voice' (McFague 1993:12). The church could learn from this to foster synergy and cooperation in its ranks for collective well-being.

Mismatch between programmes and resources

The mismatch between programmes and resources is another blind spot observed in relation to these churches. For instance, three participant churches (i.e. URCSA, ELCSA and Letlhabile Baptist) own well fenced property with borehole water in the yard, yet none of them have initiated a viable agricultural project, which has the potential to become a small business in those contexts. Further, all these churches possess building facilities of considerable decency, yet the use of these facilities is not maximised. With the exception of Letlhabile, these facilities remain locked 3-4 days a week.

This mismatch could be also related to a lack of strategic vision for local transformation, which seems to be the case for these participant churches.

The local context not being taken seriously

Another obvious blind spot of these churches is neglecting to take community issues seriously in their respective contexts, even though they are aware of these. Being aware is not the same as being engaged in facilitating solutions to community challenges. The praxes of these churches seem to suggest that these churches are hesitant to step into the public community space as catalysts of change. As a result, none of them has a public contextual praxis, which could foster social justice in the face of unemployment and socio-economic injustice prevalent in their immediate contexts. It appears as if these churches are not adequately being 'people who represent God to the world' (Wright 2010:114) and they are not adequately building the church-household as part of the societal household, in oikos terms.

Together, these blind spots and weaknesses have a negative impact on the churches' relevancy in these contexts including LED.

Contemporary relevance and ministry

Given the socio-economic, historical and political context of injustice and poverty that are realities in townships including the weaknesses and blind spots associated with the churches as described by the church leaders who participated in this research, the issue of ministry relevance is an important one. I surmise that the contexts of S and H will greatly benefit from churches as follows: (1) beyond dependency by developing their own economic engines to sustain them, (2) beyond charity by initiating socio-economic and agricultural, long-term sustainable development programmes that restore the livelihood of the oikos, (3) beyond escapist theologies by stepping into the public community space to develop public contextual theologies for social justice, (4) beyond clergy versus laity restraints by developing an integrated shared ministry which mobilises all assets of the church and community for collective well-being and (5) beyond despair by drawing and applying biblical frameworks for the economy such as the oikos.

However, looking at the praxes of these churches as described by the church leaders, they are deficient in these five considerations. As a result, they fail to become relevant change agents in their community, except in pastoral functions.

Further, contemporary relevance and ministry of the township churches could be, for example, framed around four biblical themes, that is, (1) God's preferential option for the poor, (2) God acts in history to pull down the mighty and the rich, (3) economic justice and (4) biblical understanding of wealth. It is however unfortunate that these themes cannot be discussed in length in this article. Nevertheless, it suffices to point out that the these churches will become relevant if they opt for poor people by working in such ways that those local institutions, citizen associations and gifts of individuals are reformed for the benefit of the poor who are trapped in poverty and unemployment in these townships (see Gutierrez 1988:14; Linthicum 1991:90-94; Sider 1990:46).

Furthermore, these churches should draw inspiration from God, as shown in Scriptures (see Jas 5:1 and the Magnificat, Jer 5, Is 3, Am, Jer 22, Mt 25, Am 2 & 5, Ps 94:20, Is 10), who acts in history to pull down the mighty and the rich. These churches should not withdraw from city spaces where powerful people are at work but should become witnesses in order to defeat power in its evil forms and co-work with God for the well-being of all people in the CoT (S & H) and the rest of creation. Practically, it means dealing with issues of justice, specifically with systems of social production, distribution, possession and consumption (Brueggemann 1994:175).

I will also add that God's rules for the economy provide insights for economic justice. Key issues such as land (as a fundamental basic capital) and regulations about protection of the poor as instructed in Sabbatical restitution, Jubilee law and 'practical, social and very down-to-earth'3 (Wright 2010:125) holiness described in Leviticus 19 should be at the centre of the economy. By implication, these churches - as change agents - in S and H have to end up:

working or advocating for economic generosity, economic justice in employment rights, social compassion to the weak, neighbourly attitudes and behaviours and commercial honesty in all trading transactions, while including ecological long-term sustainability as a justice issue, to name but a few, will enable them to address issues that matter in those townships. (Mangayi 2016:289)

In the process, these churches should promote the biblical understanding of wealth, which goes beyond the 'assumption that for poor people only material things matter' (McKibben 2007:218).

Resources and potential for community building and local economic development: Recommendations

Regardless of the weaknesses, blind spots and difficulties of these township churches, it is apparent that they have the basic resources and potential for community building and LED. It requires creative imagination to discern how to become agents of God's good news of the kingdom in the townships of S and H. Fundamentally, this process includes vertical and horizontal commitment embodied in God's good news of the kingdom. With reference to horizontal commitment, contextual issues related to economy, walking with the poor, lived biblical faith, social capital (mobilising the social capital from below and from the top) should be considered for the purpose of socio-economic justice and transformation. On the other hand, the vertical commitment will enable these churches to continue to proclaim the good news of the kingdom of God in Jesus' name within their congregations and in public spheres of communities' lives.

Other available resources they could tap into, which could inspire these churches to work for community building, include mission documents such as Together Towards Life of the World Council of Churches (2013), Evangelii Gaudium written by Pope Francis (2013), the 2010 Lausanne Declaration of the World Evangelical Fellowship (2010), Micah Challenge (2004) and the holistic model of Christian Community Development Association (2009). These resources provide frameworks, Bible-based rationales and insights to Christian Communities for involvement in addressing poverty and socio-economic injustice in the world today. These resources could indeed be helpful to local townships of Tshwane (S & H) determined to work for transformation. Further, Christians, members of these churches who are engaged in politics, should be mobilised to promote a biblically balanced view of the principles of the good news of the kingdom of God in the public sphere. In addition to teaching such a view, local pastors and preachers have the responsibility of providing contextual preaching geared to build communities. However, as these churches mobilise their resources and potential for community building, they must guard themselves against political groups who will always try to co-opt the church into their agenda.

With specific reference to the economy, these township churches as change agents must highlight the fact that there is a prevailing injustice embedded into the current economic system. Therefore, the churches are required to advocate for the need for the right kind of programmes to redistribute wealth, that is, to place an emphasis on sharing which complies with God's rules of the economy. These churches must work, in partnership with other role players, for the empowerment of the poor to reach the point where they own the capital needed for their own development. In short, these churches are called to mobilise all their assets, resources and potential to ignite and drive socio-economic change within and in the public sphere of the life of the communities of S and H. Lastly, it must be borne in mind that economic injustice/justice issues can only be dealt with successfully within a long-term ecological sustainability as a justice issue framework.

Conclusion

In the context of this research, the personal interviews with church leaders confirm that township churches and their communities still bear the legacy of apartheid. These leaders and their churches minister mostly to Africans who still struggle to survive.

In relation to LED, the praxis matrixes of these township churches as described by the church leaders confirm also that these peripheral churches have important assets such as physical and institutional structures, spiritual and moral foundations and access to deprived grassroots and at-risk communities, contacts with public offices, cross-cultural relationships and a predisposition to care for the poor. These assets can be further mobilised to generate vision, motivation and responsibility for a public theology in such a way that township churches become relevant and visible strategic change agents for LED in Tshwane even though they might have some weaknesses and blind spots in their mission orientations.

This article points to a set of recommendations as discussed in the previous section. Insights gained from the leaders of these churches confirm that with creativity and determination township churches would certainly become viable change agents for LED in Tshwane. Finally, this empirical research makes a distinct missiological contribution, which should incite even deeper exploration into mission as LED.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationships which may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

References

Blakely, E.J., 1994, Planning local economic development: Theory and practice, 2nd edn., Sage, London. [ Links ]

Bosch, D., 1991, Transforming mission: Paradigm shift in theology and mission, Orbis Books, Maryknoll, NY. [ Links ]

Bonhoeffer, D., 1971, Letters and papers from prison (enlarged edition), SCM Press, London. [ Links ]

Brueggemann, W., 1994, A social reading of the Old Testament: Prophetic approaches to Israel's community life, Fortress Press, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Christian Community Development Association, 2009, Holistic model of development, viewed 12 April 2015, from https://www.ccda.org/resources [ Links ]

Conn, H.M. & Ortiz, M., 2001, Urban ministry: The kingdom, the city and the people of God, Intervarsity Press, Downers Grove, IL. [ Links ]

Florin, H., 1967, Lutherans in South Africa: Revised report, Lutheran Publishing Co, Durban. [ Links ]

Francis (Pope), 2013, The Apostolic Exhortation, Evangelii Gaudium, of the Holy Father Francis to the bishops, clergy, consecrated persons and the lay faithful of the proclamation of the gospel in today's world, Vatican Press, Rome. [ Links ]

Garaba, F. & Zarvedinos, A., 2014, 'The Evangelical-Lutheran Church in South Africa: An introduction to its archival resources held at the Lutheran Theological Institute (LTI) Library, and the challenges facing this archive (Part 1)', Missionalia 42(1/2), 5-28. [ Links ]

Gutierrez, G., 1988, A theology of liberation, fifteenth anniversary edition with a new introduction, Orbis Books, Maryknoll, NY. [ Links ]

Hoekendijk, J.C., 1966, 'Notes on the meaning of mission', in T. Wieser (ed.), Planning for mission: Working papers on the new quest for missionary communities, pp. 37-48, US Conference for the World Council of Churches, New York. [ Links ]

Kritzinger, J.J., Meiring, P.G.J. & Saayman, W.A., 1994, On being witnesses, Orion Publishers, Halfway House. [ Links ]

Kritzinger, J.N.J., 2008, 'Faith to faith: Missiology as encounterology', Verbum et Ecclesia 29(3), 764-790. https://doi.org/10.4102/ve.v29i3.31 [ Links ]

Kritzinger, J.N.J., 2013, Integrated theological praxis, 'Capstone' module, University of South Africa, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Latini, T.F., 2011, The church and the crisis of community: A practical theology of small group ministry, Eerdmans Publishing Co, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Linthicum, R., 1991, City of God, city of Satan: A biblical theology of the urban church, Zondervan Publishing House, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Mangayi, L., 2016, 'Mission in an African city: Discovering the township church as an asset towards local economic development in Tshwane', PhD thesis, Department of Christian Spirituality, Church History and Missiology, University of South Africa, viewed n.d., from http://hdl.handle.net/10500/22674 [ Links ]

McFague, S., 1993, The body of God: An ecological theology, Fortress Press, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

McKibben, B., 2007, Deep economy: The wealth of communities and the durable future, Times Books Henry Holt and Company, New York. [ Links ]

Micah Challenge, 2004, Halve poverty in 2015, viewed 12 April 2015, from http://www.micahchallenge.org/resources/category/11 [ Links ]

Musasiwa, R., 1996, 'Theological reflections', in T. Yamamori et al. (eds.), Serving with the poor in Africa: Cases in holistic ministry, pp. 58-70, MARC Publications, Monrovia, CA. [ Links ]

Nűrnberger, K., 1999, Prosperity, poverty and pollution: Managing the approaching crisis, Cluster Publications, Pietermaritzburg. [ Links ]

Parnell, C., 1995, Stinkwater Mission, viewed 12 January 2014, from http://www.cmf.org.uk/publications/content.asp?context=article&id=2389 [ Links ]

Pieterse, H.J.C., 1993, Praktiese teologie as kommunikatiewe handelingstoerie, RGN-Uitgewers, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Rabe, M. & Lombaard, C., 2012, 'Give us this day our daily bread - Clergy's lived religion in Pretoria Central areas', Acta Theologica 31(2), 241-263. [ Links ]

Roozen, D.A., McKinney, W. & Caroll, J.W., 1984, Varieties of religious presence, The Pilgrim Press, New York. [ Links ]

Roy, K., 2000, Zion City RSA, The South African Baptist Historical Society, assisted by the Department of Church History, University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

Sider, R.J., 1990, Rich Christians in an age of hunger, Word Publishing, Dallas, TX. [ Links ]

Steward, J., 1994, Biblical holism: Where God, people and deeds connect, World Vision International, Melbourne, Australia. [ Links ]

Stott, J.R., 2003, Life in Christ, Baker, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Stott, J.R.W., 1975, Christian mission in the modern world, Intervarsity Press, Downers Grove, IL. [ Links ]

The Lausanne Movement, 2010, Cape Town Declaration, viewed 12 April 2015, from http://www.lausanne.org/content/covenant/lausanne-covenant [ Links ]

The Oikos Study Group, 2006, The Oikos Journey: A theological reflection on the economic crisis in South Africa, The Diakonia Council of Churches, Durban, South Africa. [ Links ]

Uniting Reformed Church in South Africa (URCSA), 2012, Minutes of the Sixth General Synod of URCSA 2012, viewed 03 December 2013, from http://www.vgksa.org.za/WhoAreWe.asp [ Links ]

Van Engen, C.E., 1991, God's missionary people: Rethinking the purpose of the local church, Baker Book House & San Francisco, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Van Schalkwyk, A., 2008, 'Women, Ecofeminist theology and sustainability in a post-Apartheid South Africa', Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 130, 6-23. [ Links ]

World Council of Churches (WCC), 2013, Together towards life: Mission and evangelism in changing landscapes, WCC Publications, Geneva. [ Links ]

Wright, C.J.H., 2010, The mission of God's people: A biblical theology of the church's mission, Zondervan, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Lukwikilu Mangayi

mangal@unisa.ac.za

Received: 11 Mar. 2018

Accepted: 31 May 2018

Published: 08 Aug. 2018

Note: This study is a reworked Chapter 3 of the author’s doctoral thesis completed in 2016 at the University of South Africa (see Mangayi 2016).

1 . See http://www.baptistunion.org.za/

2 . Latini uses multidimensional Koinoinia to denote multidimensional union and communion of the greatest possible intimacy and integrity. This koinonia constitutes the being of God, the church, all humanity, even the cosmos. It defines the identity of the church and orders all its practice. Koinonia is multidimensional when it comprises five interlocking relationships: (1) the Koinonia of the Trinity; (2) the Koinonia of the Incarnate Son, Jesus Christ; (3) the koinonia between Christ and the church; (4) the koinonia among church members; and (5) the koinonia between the church and the world.

3 . Italics in original.