Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

HTS Theological Studies

On-line version ISSN 2072-8050

Print version ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.74 n.1 Pretoria 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v74i1.4949

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Understanding power struggles in the Pentecostal church government

Mangaliso Matshobane; Maake J. Masango

Department of Practical Theology, Faculty of Theology and Religion, University of Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

This article highlights the power struggles that the Pentecostal church experiences in its church governance. These power struggles become very contentious to a point where members take each other to legal courts, which ends in multiple schisms that tarnish the image of the Pentecostal movement. Most literature on church conflicts approach power struggles as caused by personality disorders. This article seeks to highlight a different approach where power struggles are more a result of structural factors than personal ones emanating from a hybrid nature of polity in the Pentecostal church and other structural factors of conflict like finances, education and leadership. Finally, an educational pastoral care methodology is proposed for this article.

Introduction

Power struggle is a phenomenon that affects various institutions that have a hierarchical system, be they governmental, business or religious. Therefore, the church is not an exception when it comes to power struggles, and as much as this phenomenon affects all denominations of the church, the focus of this research is on the Pentecostal church with the research specifically located in Buffalo City Municipality in the Eastern Cape. The findings of this research will also benefit other denominations who can apply them within their context.

Greenfield in his book, The Wounded Minister, highlights reasons for power struggles in the church based on a survey conducted by a leadership magazine issued in the winter of 1996 on the Protestant clergy. The survey reveals that power struggles can manifest through various forms, namely: personality conflicts between the pastor and the congregation or the church leadership (at 43.0%); conflicting interpretation on the vision of the church (at 17.0%); financial strain in the church (at 7.0%); theological differences (at 5.0%); moral dereliction (at 5.0%); unrealistic expectations (at 4.0%); and other general reasons (at 19.0%) (2001:15). In another survey conducted by Barfoot, Winston and Wickman (2005:12), 108 pastors of evangelical churches across denominational lines put conflict caused by a different interpretation of the church vision (at 41.67%) and personality conflict with board members (at 35.19%) as the top two reasons for power struggles. Based on these statistics, it is evident that power struggles in the church emanate from both personality conflict and structural conflict.

Much has been written on church conflict as a result of personality disorders, with authors using different names to describe the instigators of conflict such as 'Antagonists' (Haugk 1988), 'Clergy killers' (Rediger 1997), 'Troublesome people' (Oates 1994), 'Attackers' (Maynard 2010) and 'Dragons'(Shelley 2013), etc. Some of the authors have used these descriptive names as their book titles.

There is not much written on structural conflict, especially in relation to the nature of church polity within the Pentecostal church. It is the aim of this article to highlight this structural conflict. This article will argue that structural conflict in the Pentecostal church is a major contributor to the power struggles experienced.

This article is a result of empirical research conducted by the author in 2017 in the Eastern Cape, Buffalo City Municipality, where church leaders or overseers, pastors, elders, deacons and congregants were interviewed. All the participants had experienced a power struggle in their congregations. The participants were selected from four classical Pentecostal churches, two independent Pentecostal-charismatic churches and one African initiated church. The total number of participants was 20.

The qualitative genre used was a grounded theory where 10 categories or themes emerged in the findings. These 10 themes emerged in answering a question on reasons for power struggles in the Pentecostal church, namely: polity, lack of money, lack of education, immaturity of leadership, incompetent leadership, insecurities, transitioning from one polity to the other, secular style of leadership, ulterior motives and healing from previous wounds. These are in order of priority. The top five were more prevalent in the data and therefore they are the focus of this article.

The article will discuss the dynamics of conflict as a basis for power struggles in the Pentecostal church. Various theories and perspectives on conflict will be discussed in trying to understand power struggles. The findings of the research based on the five themes will show how structural conflict emerges as the major reason for power struggles. The hybrid nature of Pentecostal polity will be discussed as one of the contributors of power struggles.

Understanding conflict

Avis in his book, entitled Authority, Leadership and Conflict in the Church, argues that 'The exercise of power necessarily generates conflict. Conflict and power feed on one another' (1992:119). Therefore, we cannot talk about power struggles without referring to conflict. Power struggles and conflict are therefore interrelated and in this article they will be used interchangeably.

Theories of conflict

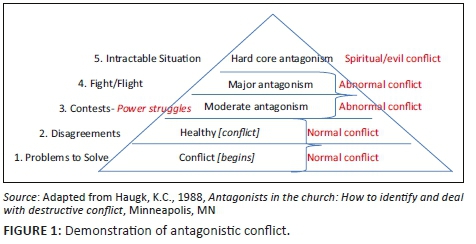

Haugk in his book, Antagonists in the Church, uses Leas' theory on conflict and explains how conflict starts from a problem-solving level, and when there is no solution at this level it escalates to disagreements. At this stage, it is still regarded as a healthy conflict. Disagreements when unresolved become contentious, which is where power struggles begin. The fourth and the fifth levels are the ones where the conflict is at its worst, and usually at this level it is very difficult to resolve the impasse (1988:31-35).

He then goes on to divide the antagonists into three categories, namely the hard core, the major and the moderate. Hard core antagonists are those who are psychotic and are out of touch with reality. They possess an insatiable desire to make trouble and are very tenacious about it. Major antagonists are those who have personality disorders but are not psychotic, although they have deep-seated personality problems, but they are not out of touch with reality. Moderate antagonists are a milder version of the two. They never go out of their way to be antagonistic, unless the opportunity presents itself. All three types of antagonists can be malicious in their motives and impact (Haugk 1988:27-30).

Lea states that 'the first two levels are easy to work with; the third is tough; the fourth and fifth are very difficult and impossible' (1985:16). Rediger further builds on Leas and Haugk's theory by stating that conflict can be normal, abnormal, spiritual or evil (1997:63-65). Abnormal conflicts become more complicated when those involved have personality or mental disorders. He goes to lengths in describing these individuals (1997:57). He further states that there is a level higher than abnormal conflict, and this is spiritual conflict. Spiritual conflict is when those who are antagonists become so determined to oppose others that they develop 'evil' strategies to annihilate them. Rediger describes those operating at this level as 'clergy killers'. He says that they 'resort to sinful tactics without remorse [with] persistent energy for their nefarious causes …' (1997:58).

Figure 1 shows how the three theories on conflict are interlinked.

We can conclude by deducing from Figure 1 that conflict by itself can be a healthy process. Disagreements are normal when resolving a problem. It is only if the disagreements escalate to the level of contestation that power struggles begin and disagreements become abnormal and therefore unhealthy.

Structural conflict

Galtung, a Norwegian sociologist, proposes that conflict has three interlinked components. These are attitude, behaviour and internal contradictions. Conflict can begin from any of these three components. A negative attitude towards someone can lead to internalising negative internal contradictions, which will manifest in a negative behaviour (1996:70). He further states that there are two dispositions in conflict. One is called an actor conflict while the other is a structural conflict. An actor conflict occurs when a person is conscious or cognitive of their inner contradictions, and therefore chooses a specific attitude and behaviour to align with their inner contradictions. They choose to act in a particular way; hence, it is called the actor conflict. However, the structural conflict is when a person is not conscious or fully cognitive of their internal contradictions and develops a false image of what the problem is; as a result, a false attitude develops, which informs a false or inaccurate behaviour (1996:74-76).

Demmers provides a socio-economic example of a structural conflict where unemployed workers tend to blame migrants who are preferred by employers and therefore develop hateful attitudes towards them which lead to aggression, whereas the actual cause of the problem is not the migrants but the pressure that the global markets have on the economy, causing employers to choose cheap labour so that their business can stay afloat. So the conflict is caused by the structure of the economic system, which impacts on the social system; hence, it is called a structural conflict (2012:58-60).

The same structural conflict can be experienced in the context of a church. A conflict between a pastor and the church board or elders can be caused by a difference in interpretation of church polity and end up becoming a personality conflict, whereas the problem is structural and not personal. In the Pentecostal church, this is most likely because the nature of church government is usually a hybrid of two or more governance structures from different church traditions. Warrington, referring to Rowe (1996), states that: 'some Pentecostal denominations function along Congregational or Presbyterian lines where the concept of koinonia is more easily reflected, others are Episcopal …' (2008:137).

Example of a structural conflict

It is most likely that some power struggles in the Pentecostal church are caused by structural conflicts where the actual cause of the conflict is not interpersonal, but it is based elsewhere yet tends to manifest itself interpersonally. The latter is the experience of the author where he served as a pastor in an independent Pentecostal church, which had a Presbyterian model of polity where the elders of the church had the final authority over the direction of the church. The author on the other hand had a background of an independent Pentecostal church with an Episcopalian model of polity where the pastor as a founder was like a bishop who has a final word on the direction of the church. The author accepted the call to pastor this new church assuming that the polity was the same because both these congregations were independent Pentecostals. The elders also were under the impression that their new pastor will not have a problem with their church polity because he also came from an independent Pentecostal church. The relationship lasted only three years and it followed the stages of conflict as demonstrated in Figure 1. The first year the conflict was civil and normal with a few disagreements as both parties were trying to solve regular ministry problems. The second year the conflict was abnormal when power struggles began because of the different styles of ministry informed by different church polity models to a point where there was major antagonism between both parties. The third year the conflict reached an intractable, evil stage and the pastor was forced to resign, which unfortunately caused a major church split with the majority of members leaving with the pastor. During the last 2 years of the power struggles, the conflict became personal and was made worse by some personality disorders. However, the problem was not resolved because it was structural and not personal. The church continued to lose every pastor they invited after every 2-3 years because they kept calling pastors with a different church polity background than theirs. At times, some of the pastors had a similar background as the elders in terms of church polity, but with a different interpretation from the elders.

Therefore, Pentecostal polity is shaped by various church traditions and therefore open to various forms of interpretation. This is what causes power struggles. We will now turn to the findings of the research to confirm whether structural conflict is a major cause of power struggles.

Findings

Five categories emerged as primary causes of power struggles. These categories are listed in order of priority from the most prominent to the least prominent, namely: polity, lack of money, lack of education, incompetent leadership and immature leadership. Of the participants, 65% named polity as the number one cause of power struggles; 40% named lack of money and lack of education as the cause of power struggles, making them the second highest; and 30% named incompetent and immature leadership as the cause of power struggles, making them the third highest group.

It is worth noting that categories 1-4 are not dealing with interpersonal relations but with structural ones. Polity is an institutional matter while money is an economic matter. Education is a social matter and competent leadership is a matter of skill. None of these allude or point to any disorder in personality or behaviour. Immaturity on the other hand can be classified as an interrelation matter. When leaders show signs of immaturity, it could be as a result of some form of personality disorder. That this category was third in prominence together with competence shows that power struggles are not primarily caused by personality conflicts, but by structural conflicts. Personality conflicts can feature secondarily in the whole picture of conflict. Let us take a closer look at the five categories.

Polity

Under polity, there are four outcomes, which are set in order of priority:

1. A high number (40%) of participants indicated that although polity on managing power struggles was available in their congregations, it was never used or followed. The only time church polity would be referred to during power struggles was to favour one party against the other.

2. The second highest number (30%) of participants indicated that although polity on power struggles was referred to in their congregation, it was usually misinterpreted or misread.

3. There were those who indicated a change from one polity tradition to the other in their congregations. Not many congregations changed in polity, but those who did (20%), needed a lot of undergirding because the process was not an easy one.

4. There were cases, although a very low number (10%), of participants who indicated that they did not have a church polity on power struggle. The problem with such a state of affairs was that when power struggles erupt, it tears the church apart because of a lack of any documentation that could give guidance or bring correction to the chaos.

Lack of money (socio-economic capacity)

The use, misuse and abuse of money played a significant role in the power struggle in the congregation. Money or financial resources came up at 40% of the total responses of participants, making it the second highest. Most of the participants pointed to the influence of money as an instrument of power, whether that influence was positive or negative. Literature also confirms this assertion about money, in a case where wealthy members of the church use their financial capacity to sway things in their direction. Greenfield confirms that: 'denominational officials fall into this latter category of appeasement, influenced by their desire not to lose the financial support of the congregation whose minister is under fire' (2001:29-30).

Lack of education

The lack of education, or the possession thereof, was one of the high (40%) contributors and influencers in a power struggle. It shared a similar response with money and, therefore, positioned itself as an instrument of power. Leaders who were less educated felt inferior to members of the congregation who were more educated. Leaders who were more educated felt superior. When these leaders are on opposite sides, power struggles are more likely to occur. The inferiority makes others so insecure that they start over reaching in their authority, especially if they possess some form of power based on their position in the congregation. The conclusion on this finding was that being educated gave advantage in a power struggle. This was also confirmed by literature on 'power' in the classical work of Foucault when he says '… it is not possible for power to be exercised without knowledge, it is impossible for knowledge not to engender power' (1980:52). In other words, knowledge privileges one person above the other and therefore gives them power over the other.

Incompetent leadership

The responses of participants (30%) pointed in many cases to leaders who because of lack of leadership skill were not able to steer the congregation in the right direction during the time of power struggles. The conclusion on this finding was that it is a leader's responsibility to ensure that they are properly skilled and always a step ahead of congregants in matters of leadership, including in all other challenges of leadership.

Immature leadership

The final category that causes a power struggle was the immaturity of leaders whether in character, spirituality or emotionally, etc. Participants (30%) alluded to the immaturity of leaders as a contributor in power struggles. In some cases, this immaturity is found in wounded leaders who carry internal pain, project it on others, and carry it out in a destructive way. Greenfield points out that sometimes immaturity in leadership can reflect in pathological ways because of an abnormal attitude and behaviour in times of power struggles. These may not necessarily be psychotic or out of touch with reality, but a reflection of deep-seated personality problems (2001:39).

It is clear from the findings that Pentecostal polity is not the only structural problem that causes power struggles but also money, education and leadership. Therefore, there is a need to pastorally care for the Pentecostal church through educating it on how to understand the constitution of its polity and by understanding the various traditions of polities that make up a polity of a particular congregation in the Pentecostal church. There is also a need to educate the church on the role that money, education and leadership plays in matters of governance in the Pentecostal church. A pastoral care methodology that will care for Pentecostal churches in these areas will be our next discussion.

Pastoral care methodology

Gerkin in his book, Introduction to Pastoral Care, states how pastoral care must be administered as pastoral education. It is the responsibility of the pastoral caregiver to educate the people of God on what it means to care for the faith they profess, the community of believers they belong to and helping them to be stable in their faith amidst a secular culture around them. He confirms this educator role of pastors when stating that 'Pastors Have acted as pastoral educators in their caregiving' (1997:95):

· On polity, the pastor as educator must help the church to conduct a thorough research on the composition of their polity and its various traditions (be they Presbyterian, Congregational or Episcopalian) with all the pros and cons properly weighed. A workshop should be organised where experts on these various traditions of church polity and experts in Pentecostalism will be invited to present their knowledge on each tradition and its history in a workshop. Out of this workshop each Pentecostal congregation will make an informed decision on which church polity will suit them best. It is not the intention of this article to suggest a uniform polity for the Pentecostal church but to help educate each congregation within the Pentecostal church to fully understand the strengths and limitations of their chosen polity. This knowledge will go a long way to minimise power struggles in matters of church government.

· On money, leaders, especially pastors, must be educated on how to be financially viable outside the congregation. Each pastor must learn how to be resourceful in money matters so that they are immune to the temptation of being manipulated through money. They must be quick to discern financial manipulations from congregants. This matter needs each pastor to be spiritually matured in discernment and in resisting temptation. Discussion during pastor or leader's forums can address such subjects in order to strengthen those who are weak in this area. It is good for a pastor to depend on God for provision by working with his or her own hands and supporting themselves financially. Total dependence on the congregation can give grounds for manipulation and control.

· On education, as much as the role of informal education is recognised in the Pentecostal church, Pastors and leaders must be encouraged to have some form of formal education, especially in ministry from reputable theological institutions. For those pastors or leaders who may be illiterate or who have some form of challenge with formal education, oral tuition can be offered to them in the language and level they can understand. This will help them in being confident when they do their ministerial duties. It will encourage their congregants to take them seriously when they stand to execute their duties, especially when congregants are educated people. The higher the level of education of a pastor or leader in the church, the better the quality of his or her ministry is likely to be. There are also other forms of educating pastors and leaders that are not formal but are equally important, like attending equipping or training conferences for pastors and church leaders and developing a habit of reading books on various ministry topics including those that deal with challenges in ministry.

· On Leadership, every pastor or leader in ministry must always sharpen themselves with leadership materials that can be very helpful in leading the church. The church must from time to time take their leaders for special leadership training seminars so they can stay abreast of cutting-edge leadership material. Specialised training must also be provided, which deals with subjects like power struggles and how to manage them. Experts must be invited who can help pastors or leaders in proactively preparing themselves for all kinds of leadership challenges. Improving the skills of leaders must be a continual practice of the church and leaders must not wait until a crisis arises. A pastor or leader must seek to be holistically matured. There must be a genuine desire to grow and be a better person in all areas of life. There are many habits a leader or pastor will have to develop in order to keep growing and maturing. One of the best ways to maturity is to study the lives of other leaders or pastors who are senior and matured in ministry. If it is possible, one could even ask to be mentored by them. Having a mentor who will hold one accountable in ministry is one of the ways one can quickly mature.

African methodology

It is worth noting that the African way of resolving conflict is another methodology that can be used in pastorally caring for the Pentecostal church. Odegi-Awuondo (1990) and Osamba (2001) give us the African perspective of how conflict was handled. It was customary for elders to sit and adjudicate over matters of conflict. Their decision was final and was respected by all. There were binding covenants that were entered into which when bridged brought all kinds of misfortunes. This is what kept the community orderly.

In implementing this strategy, church elders or a group of senior and matured congregants can be trained and set to deal with day-to-day disputes of the congregants. They must be trained to understand the authority they carry because whatever they say will happen. They must be taught that God will back up their words of correction, rebuke and guidance. They are the ones who will be available if there are disputes in the church. The congregation and these elders need to be taught that the collective is better than an individual. The words that the elders carry represent the view and opinions of a collective. Mucherera (2009) states that:

In the African context, one's life and stories unfold within the context of a community and it is therefore acknowledged that it is within community relations that health can be achieved. (p. 101)

This African approach of giving a group of select matured elders who possess spiritual authority in the congregation to adjudicate on matters of conflict will lead to reconciling parties who have wronged each other and not seeking to judge who is right or wrong.

Conclusion

Structural conflict is the primary cause of power struggles in matters of governance in the Pentecostal church. Most literature on church conflict does not put much emphasis on structural conflict but on interpersonal conflict as a cause of power struggles. This article has used the theories of conflict and how they are interlinked in describing how conflict develops at different stages. The findings of the research on power struggles have confirmed Galtung's theory of structural conflict as the main cause of power struggles. The hybrid nature of the Pentecostal church polity surfaced as the number one cause for power struggles. A pastoral care methodology of educating the pastor, the church leaders or board and the congregation on structural challenges of polity, money, education and leadership as the main causes of power struggles is proposed in this article in order to help the Pentecostal church to have a better approach in resolving its power struggles.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

M.M. and M.J.M. declare that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

Both authors equally contributed to the research and writing of this article.

References

Avis, P.D.L., 1992, Authority, leadership and conflict in the church, Trinity Press international, Philadelphia, PA. [ Links ]

Barfoot, D.S., Winston, B.E. & Wickman, C., 2005, Forced Pastoral Exits: An exploratory study, School of leadership studies, pp. 1-19, viewed 02 May 2018, from http//:www.googlescholar [ Links ]

Demmers, J., 2012, Theories of violent conflict: An introduction, Routledge Taylor and Francis Group, UK. [ Links ] Foucault, M, 1980, Power/ knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings 1972-1977, Colin Gordon (ed.), Pantheon books, New York. [ Links ]

Galtung, J., 1996, Peace by peaceful means: Peace and conflict, development and civilization, Sage, London [ Links ]

Greenfield, G., 2001, The wounded minister: Healing from and preventing personal attacks, Baker Books: A division of Baker Publishing Group, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Haugk, K.C., 1988, Antagonists in the church: How to identify and deal with destructive conflict, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Leas, S.B., 1985, 'When conflict erupts in your church: An interview with Speed B. Leas', in D.B. Lott (ed.), Conflict management in congregations (harvesting the learnings), pp. 11-19, Plymouth, United Kingdom. [ Links ]

Maynard, D.R., 2010, When sheep attack, Book Surge Publishers. [ Links ]

Mucherera, T.N., 2009, Meet me at the Palaver: Narrative Pastoral counseling in postcolonial contexts, Cascade Books, Eugene, OR. [ Links ]

Oates, W.E., 1994, The care of troublesome people, Alban institute publication, New York. [ Links ]

Odegi-Awuondo, C., 1990, Life in the balance. Ecological sociology of Turkana nomads, ACTS Press, Nairobi. [ Links ]

Osamba, J., 2001, 'Peace building and transformation from below: Indigenous approaches to conflict resolution and reconciliation among pastoral societies in the borderlands of eastern Africa', African Journal on Conflict Resolution 2 (1), 33-42. [ Links ]

Rediger, G.L., 1997, Clergy killers: Guidance for pastors and congregations under attack, Westminster John Knox Press, Louisville, KY. [ Links ]

Shelley, M., 2013, Ministering to problem people in your church: What to do with well-intentioned dragons, Bethany House Publishers: A division of Baker Publishing Group, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Warrington, K., 2008, Pentecostal theology: A theology of Encounter, T&T Clark, London. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Maake Masango

maake.masango@up.ac.za

Received: 26 Feb. 2018

Accepted: 08 May 2018

Published: 22 Oct. 2018