Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

HTS Theological Studies

On-line version ISSN 2072-8050

Print version ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.73 n.4 Pretoria 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v73i4.4582

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v73i4.4582

The labyrinth as a symbol of life: A journey with God and chronic pain

Lishje Els

Department of Practical Theology, Faculty of Theology, University of Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

This article is written in the style and method of an autoethnography that focuses on the author's spiritual journey with God while living with chronic pain. The labyrinth is used as a metaphor and spiritual tool to describe this journey. The author's personal experience with religion and spirituality is described as well as the choice of moving from thinking about God being 'out there', far away and looking upon God's creation (supernatural theism) to discovering God within - God 'right here' (panentheism). The affects and effects of living with chronic pain are discussed in reference to the process of walking the circuits of a labyrinth. The role of different people who played a part in this journey is highlighted. This way of writing corresponds with a narrative way of living which concentrates on deconstruction of dominant discourses and looking for outcomes that may lead to hope and transformation. The difference between rainbow hope and reasonable hope is explained and the consequence of choosing reasonable hope is discussed. Transformation of the person through the journey becomes apparent in the article.

Introduction

In this article I present my personal spiritual journey with God and chronic pain. I am doing this within the framework of autoethnography, embedded in the paradigm of Emancipatory Critical Research. Arthur Bochner (2000; in Giorgio 2009:153) notes, 'The purpose of self-narrative is to extract meaning from experience rather than to depict experience exactly as it was lived'. This statement depicts my aim with this article. The labyrinth is used as a metaphor to describe my journey with God and chronic pain. According to Langer (2012:1), a 'metaphor is not language, it is an idea expressed by language, an idea that in its turn functions as a symbol to express something'. The labyrinth is used as a symbolic pilgrimage in many traditions. Through many ages labyrinths have been used in a spiritual manner (Schaper & Camp 2012). Walking a labyrinth can create a heightened awareness of one's own condition: physical, emotional and spiritual. This can lead to personal and spiritual growth. Geoffrion (2000:ix) states that, 'The labyrinth is an effective spiritual tool, generic in nature, and personal in application'. In this article, the labyrinth is used as a metaphor of personal and spiritual transformation.

I became very aware of the difference between organised religion and spirituality. This entailed a moving from thinking about God being out there, far away and looking upon God's creation (supernatural theism) to discovering God within - God right here (panentheism). Marcus Borg (1997) argues that:

a 'panentheistic' concept of God offers the most adequate way of thinking about the sacred; in this concept, the sacred is 'right here' as well as 'the beyond' that encompasses everything. (p. 5)

According to Borg, supernatural theism has led to the belief that God's acceptance is based on repentance for 'wrong thoughts and deeds'. There are other ways to think about the sacred and repentance.

Fulbright (2010) uses Borg's explanation of repentance in a sermon to encourage the congregation to think differently. She states: 'In his sermon Borg (2000) states, to repent in terms of its Greek roots in the New Testament means to "go beyond the mind that you have"'. According to Fulbright (2010):

The useful realm of religion is that which can help us 'go beyond the mind that we have', that which helps us resist the base pull of culture and seek our greater truth, more full connections with other people and life itself, and if we will, that which we call God. So part of self-love means to find ways to go beyond the mind that we have, to that greater mind that sees wholeness, unity, beauty, love.

Choosing to struggle with God in my struggle with pain helped me to go beyond my own mind to a place where I could experience wholeness despite having to live with chronic pain. In this article I explain the affects and effects of chronic pain on all aspects of my life. I also demonstrate and illustrate how the acceptance of my new life changed my perceptions about God and life. There are many people I met on my journey. In this article those who played a crucial part in my distress and in my healing are mentioned. Therefore, their input will also be mentioned. Yolanda Dreyer was a prominent person in my journey. Therefore, this article is dedicated to her.

Concept clarification

Autoethnography within the paradigm of emancipatory critical research

This journey follows the characteristics of an autoethnography as described by Carolyn Ellis (in Jones, Adams & Ellis 2013:10), after she saw a drawing that someone created as part of a story: 'I saw and felt the power of autoethnography as an opening to honest and deep reflection about ourselves, our relationships with others, and how we want to live'. Writing within this paradigm entails that I am authentic, honest and reflexive in the moments of everyday living. It becomes a way of examining my life and my thinking and the origin of my thinking. Autoethnographic writing means that I write my story as a survivor of chronic pain. Jones et al. (2013:10) state this as follows: '[An autoethnography] seeks a story that is hopeful, where authors ultimately write themselves as survivors of the story they are living'.

This way of writing corresponds with a narrative way of living which concentrates on deconstruction of dominant discourses and looking for unique outcomes (White 1991). This way of living entails a different way of thinking, where enquiring why we think the way we do becomes the daily mode of living one's life. Narrative living then becomes a mode of knowing. Heo (2004) puts it as follows:

Narrative is a mode of knowing and understanding that captures the richness and variety of meaning in humanity as well as a way of communicating who we are, what we do, how we feel, and why we ought to follow a certain course of action. A narrative involves facts, ideas, theories, and dreams from the perspectives and in the context of someone's life. Individuals think, perceive, interpret, imagine, interact, and make some decisions according to the narrative elements and structures. (p. 375)

A narrative is a way to describe oneself and the realities one lives in. Narrative is a way of giving meaning to one's life. Yolanda Dreyer (2003a:313) comes to the conclusion that 'narrative as a way of knowing is ideological critical and deconstructs dominant socio-cultural narratives'. She also states that the telling of one's story is much more than the pure transferring of remembered facts. Remembering is the present of the past and one's expectations are the present of the future (Dreyer 2003b:343).

In the telling of my story I deconstruct the dominant religious and cultural beliefs. In telling this story I have the expectation that it will be meaningful to you, the reader. I, as a human being, as a woman who battles to live with pain, become the text that you, the reader, will interpret. According to Dreyer (2016:644) 'a story is always open to reinterpretation'. People read stories from their own perspectives and different contexts and therefore the meaning given by the original teller of the story might change. It can thus 'have a much broader impact and significance' (Dreyer 2016:644). By telling my story I construct my reality and I choose my own preferred identity. The telling and re-telling is a process that keeps on changing the perceptions and thoughts of the reality of life. This process changes my identity and keeps on doing it, 'it is a process of always becoming' (Sclater 2003; cf. Sclater in Bainhaim, Sclater & Richards 2002:140).

Writing this article as an autoethnography also indicates that the personal is the professional where my personal life and my professional life as a psychologist cannot be separated (Els 2000:18-20). As a psychologist I cannot not know what I know regarding thoughts, feelings and behaviour. This knowledge exaggerated the pain at times because of self-doubt and guilt that entered the situation (see Patient & Orr 2004:33, 244; Berendes et al. 2010:174-182).

This way of writing also correlates with action and feminist research strategies (cf. Bolak 1997; Charmaz & Mitchell 1997; De Vault 1997; Hertz 1997; Lather 1991; Reinharz 1992, 1997; Smith 1992; Weingarten 1997, 2000) where multiple realities are preferred, and people and their words and actions are always seen within a social context. Dale Spencer (in Reinharz 1992) states this perspective as follows:

At the core of feminist research is the crucial insight that there is no one truth, no one authority, no one objective method which leads to the production of pure knowledge … feminist knowledge is based on the premise that the experience of all human beings is valid and must not be excluded from our understandings. (p. 7)

This article is about my personal, subjective journey. My story with God and chronic pain is shared with you, the reader. You will have your own experience when you read this. All our understandings of this journey are valid. 'The process becomes part of the product' (Reinharz 1992:212). This article introduces my personal journey with God and chronic pain. My own attitudes, beliefs, perceptions and values that are seated in my own culture - an Afrikaans woman who grew up in the Dutch Reformed Church and married a minister in the Netherdutch Reformed Church of Africa - are reflected in this narrative.

The telling of my story helps me to understand my own spiritual growth process and the pain I suffered and still suffer in a more meaningful way. It helps me to come to terms with it (again). This is a process that is never-ending. Carolyn Ellis (2002) states this process of sharing one's pain as follows:

… engaging in the process of uncovering, going deeper inside yourself through autoethnographic writing, can stimulate the beginning of recovery. Expressing my feelings vulnerably on the page invites others to express how they feel, comparing their experiences to mine and to each other's. (p. 401)

My unique experience became a way of living reflexively and challenging my own assumptions, defences and fears. I learnt that I had to live consciously in the moment and had to consider and reconsider my thinking (Jones et al. 2013:10). 'We are positioned in particular discourses, which affect our preferred ways of being' (Els 2000:149). I therefore had to look at and assess the discourses that are embedded in my thought processes. The Afrikaans culture and the religion of the Dutch Reformed Church and later the Netherdutch Reformed Church positioned me in discourses of 'God is almighty and watching over us and God is also watching what we are doing and we will be judged according to our deeds', and 'you have to be strong and not show how you feel about things'.

Although a discourse as such is not positive or negative, some discourses are dominant and therefore their effects have more power in our lives. Our sense of who we are and what we are allowed to think, say and do, derives from our position in a particular discourse (see Foucault 1980:93). As an Afrikaans woman, I was positioned in a subject position. In my doctoral study I wrote the following (Els 2000:138): 'When we accept or fail to resist the subject position, we are obliged to live according to the specific rules of that particular subject position in that particular discourse'. This is exactly what happened and it was only when physical pain got hold of me, and there were no answers to my many questions that I openly started to challenge the above-mentioned discourses (cf. Burr 1995; Davies 1991; Els 2000; Foucault 1972; Mills 1997; Parker 1989; White 1997).

Autoethnography is the choice of this article because it is transformative and it 'changes time, requires vulnerability, fosters empathy, embodies creativity and innovation, eliminates boundaries, honors subjectivity, and provides therapeutic benefits' (Custer 2014:1).

Religion and spirituality

There are many different definitions of religion and spirituality. I agree with the explanation of Schutte (2016):

Religion is organised, close-minded and intolerant whereas spirituality is extremely individualised, open-minded, tolerant and universal. It is accessible to all people, no matter what their particular beliefs. (p. 2)

In my experience religion usually entails adhering to a certain dogma or belief system. To put it briefly, religion is a set of beliefs and rituals that aim to get a person in the right relationship with God. Therefore, Émile Durkheim's (1915; cf. Aldridge 2007:67) definition speaks to me:

A religion is a unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things, that is to say, things set apart and forbidden - beliefs and practices which unite into one single moral community called a Church, all those who adhere to them. [Religion is] the self-validation of a society by means of myth and ritual. (p. 47)

Phipps (2012:179; in Schutte 2016:3) defines spirituality as 'the human desire for connection with the transcendent, the desire for integration of the self into a meaningful whole, and the realisation of one's potential'. Spirituality today includes belief in a higher power that is beyond the known and observable realm. To me that power is God. It also includes personal, sacred experience(s), or an encounter with the divine within. To be spiritual means that one has the expectation that personal growth and transformation will take place. This is what I experienced in my spiritual journey with God.

Labyrinth

The labyrinth predates Christian history. There are many divergent stories regarding the origin of the labyrinth (cf. also Geoffrion 2000; Schaper & Camp 2012:2-13; Ward 2006:6-13). It is clear that Christians have been using the labyrinth as a spiritual tool as early as in the Medieval times (cf. www.labyrinthbuilders.co.uk/about_labyrinths/history.html). The labyrinth in the Chartres Cathedral dates back to approximately 1205 (Ward 2006:10). In 1631 John Amos Comenius, a Czech philosopher, pedagogue and theologian from the Margraviate of Moravia, wrote the book, The labyrinth of the world and the paradise of the heart. In this book he describes his spiritual pilgrimage and ends with the knowledge that God is with him inside him and not far away (see 'Project Labyrinth of the World', www.labyrinth.cz).

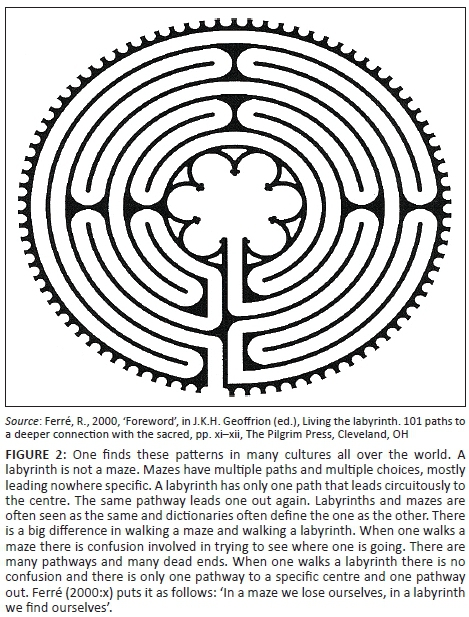

Various labyrinth patterns can be found across the world. The classical labyrinth design consists of a single pathway that loops back and forth to form seven circuits. The pathway is bounded by eight walls surrounding the centre (see Figures 1 and 2).

Christians walk the labyrinth as a symbolic pilgrimage (cf. Artress 1996; Bloos 2002:219-203; Jeanes 1979:12-15; Reed 1990). From early on Christians believed that walking the labyrinth represents the soul's journey to Christ (Schaper & Camp 2012:8). To me, walking the labyrinth is coming home to my soul where God resides. Artress (2006:20) uses the words: '… as you walk (the spiral of the labyrinth), it takes you deeper into your center'. The centre in the Chartres Cathedral is described as the New Jerusalem - this is the place where transformation has taken place (see James 1977). It is important to realise that everyone uses the labyrinth in her own way (Artress 2006:7).

There are many different ways to walk a labyrinth (Geoffrion 2000). One can walk it for personal, psychological and/or spiritual growth. A spiritual walking is completed mostly in a prayerful meditative way or with a specific question in mind. The labyrinth path is walked with devotion and openness to be enlightened during the process of walking in and out. Buechner's (1983) words fit well with walking the labyrinth. It is something to keep in mind when you stand at the mouth of the labyrinth:

Listen to your life. Listen to what happens to you because it is through what happens to you that God speaks.

…

It is in a language that's not always easy to decipher, but it's there powerfully memorably, unforgettably. (pp. 92, 94)

Chronic pain

The definition of pain has changed over the years, as new research results appeared in medical journals. Currently pain can be described as follows: '… [it] is a complex, multidimensional experience that not only has a sensory component, but also cognitive, affective, and motivational/behavioural components' (Keefe, Somers & Kothadia 2009:38). Chronic pain can briefly be described as pain lasting more than 3 months. This pain can be mild or excruciating, episodic or continuous, merely inconvenient or totally incapacitating.

The International Association for the Study of Pain ([1994] 2012) has established a taxonomy that describes the different kinds and diseases that cause chronic pain. This article does not have the scope to discuss this. The symptoms of chronic pain include:

-

Mild-to-severe pain that does not go away.

-

Pain that may be described as shooting, burning, aching or electrical.

-

Feeling of discomfort, soreness, tightness or stiffness.

The emotional toll of chronic pain can also make pain worse. Anxiety, stress, fatigue and negative thought patterns interact with the chemicals in the body and can worsen the experience of pain. Because of the mind-body links associated with chronic pain, a multidisciplinary approach seems to have the best results in treating chronic pain conditions (Keefe, Somers & Kothadia 2009).

My story

Every person is born within specific contexts and linguistic systems. We learn about our different selves and our world by talking and listening to the people who share our world with us (see Anderson & Goolishian 1992; Kotzé & Kotzé 1997). In this socialisation process we learn to speak in accepted ways and we adopt the values and ideologies of our cultures. As such the meanings that we attach to certain concepts, values and ideas shift from time to time as we are exposed to other cultures, thoughts and values in different contexts. Thomas (in Saddington 1992:44) states that: 'People do not necessarily learn from experience; it depends on the meaning they attribute to their experience and on their capacity to reflect and review it'.

My journey with God and chronic pain is a very personal story. I will reflect on my experiences as I walk this labyrinth with you, the reader.

I have always in my life been aware of God. I knew that I was God's child and that God would always take care of me. I come from a Christian patriarchal family and learnt that God was like my father … loving but strict. My paternal grandmother played the most significant role in my development as a child of God. She taught me that I had to give my heart to Jesus and then Jesus will always take care of me. She also taught me that God is a strict father who sees everything I do. I had to live according to certain rules or I knew I was going to be punished. I learnt that I had to 'be a good girl' so that God will accept me. If I did something that was not approved of, I would be told that a child of God does not do that and that I was listening to the devil. I also learnt that God watches me and sees the things that were not approved of. I had to repent quickly - even when I did not think that what I did was wrong - otherwise God was going to punish me. This religious system was the one that I grew up with. When I was in my last year of Sunday school, the minister did not allow us to be confirmed if we couldn't give him the date, time and place of our conversion to Jesus.

After school I went to the University of Pretoria to become a teacher. I was very active in the Student Congregation of the Dutch Reformed Church. The discourse of God as a punishing father continued with extra focus on the 'fact' that we have been born as sinners and that only the belief in Jesus could save us. I participated in the Youth to Youth Action that focussed on 'winning souls for Jesus'. The Reformed discourse of Jesus as personal saviour was imprinted on us.

I met my husband in the University Choir. He was a member and theological student of one of the other Afrikaans-speaking denominations that was politically more conservative but theologically more open. He introduced me into a new way of reading the Bible. The Bible was not the exact words of God. The Bible is a library of books that tell stories of people and the God they knew. Everything has to be read contextually. I am not supposed to believe in the Bible. I may believe in the God of the Bible. This was the beginning of a new way of thinking about God and the Bible.

As the life partner of a full-time minister I was actively involved in establishing Bible study groups and teaching women what the Bible actually is and how they can relate to the words that can transform their lives. I also was a high school teacher and challenged the learners about certain beliefs they had that was part of the fundamentalist view on the Bible, for example the 'gay issue'. I had a group of gifted learners in Port Elizabeth in the early 1980s. The report of the Reformed Church in the Netherlands (Gereformeerde Kerken Nederland) on being gay was just published and I took this group of 15-year-old high school learners to the then University of Port Elizabeth (today it is the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University) to listen to the discussion on this report. Afterwards we had ice-cream on the beach and one of the boys told us that he is sure that he was gay. This came as a shock to the group. One of the other boys in the group belonged to the Dutch Reformed Church of which his father was a prominent minister. My telling them that their friend was born this way and that God loves all God's children was severely challenged. It was clear that my understanding of God and the Bible was not accepted in these religious circles.

When we moved to Alberton from Port-Elizabeth, I decided to become an Educational Psychologist and enrolled at the Rand Afrikaans University (today it is the University of Johannesburg) to do a BEd, MEd and later a DEd. I had a busy private practice as an educational psychologist when I first became aware of severe pain in almost all my muscles. I was tired all day. I went to bed exhausted and in the mornings, I could hardly get out of bed. Our family doctor referred me to a physician who admitted me to hospital where many different tests were performed. In the end the diagnosis was made: Fibromyalgia.

I lived with this and kept on working. I applied for a post at the Rand Afrikaans University and got it. I managed the pain and fatigue with medicine and taking a rest when I could. Working with the master students and teaching them how to practically do therapy gave me new energy. This made me wonder whether it could be true that fibromyalgia might be existing in my head. Just as I thought that I had control over the pain and fatigue, it struck again and I knew that this was a reality that I would have to live with.

Three years later, while I was completing my doctorate, I experienced acute pain in my legs. This led to many visits to doctors all over South Africa, a back operation where a decompression in my lower back was performed and more pain. The final diagnosis by the neurosurgeon was: Peripheral Neuropathy. This was confirmed by three other specialists, a physician, a professor and anaesthetist, who was the manager of a pain clinic in Bloemfontein, and a rheumatologist. The symptoms corresponded with other distal symmetrical polyneuropathies, but I did not have any of the diseases that caused this kind of neuropathy. They could not get to the cause of the neuropathy and the verdict was that I would have to live with it. The pain could be managed by medication and changing my daily routine. I would have to learn how to manage the pain and pace my day so that there will be time to relax. This was the only way that the pain would not drain me totally. The earlier diagnosis of fibromyalgia (1997) which caused widespread muscle pain through my body as well as fatigue was re-affirmed as well. Now I had two separate diseases that caused pain in my body. I had to re-think my life and how I wanted to manage it.

As a child of God, the biggest question running around in my mind was whether God was now punishing me for telling people that God doesn't operate in a way that is not loving? Was the God that I loved and came to 'know' different than what I now believed? Was God actually like my grandmother taught me?

Affect and effects of chronic pain

Fibromyalgia is a chronic pain syndrome defined by widespread pain in soft tissue and musculoskeletal system in the body. Additionally, patients report other symptoms, predominantly disturbed sleep, fatigue and affective disturbance. It is a disease with unknown aetiology that complicates the treatment and coping thereof. It often leads to the disruption of daily functioning (Clauw 2014; Glombiewski et al. 2011:280).1

Neuropathic pain is characterised by unpleasant symptoms such as shooting or burning pain, numbness and sensations that are difficult to describe. It can be a direct consequence of a lesion or disease affecting the somatosensory system either peripheral or central level (Haanpää et al. 2011:14). Pain with neuropathic characteristics is generally more severe and difficult to treat (Dworkin 2007). It also impacts the quality of life more (Chetty et al. 2012:5).

The problem was that the doctors could not find the cause of the peripheral neuropathy, and therefore an already difficult disease to treat became impossible because the cause could not be found (Fedler 2010:56). I had to come to terms with the diagnosis of 'Idiopathic Neuropathy'. In 2012 I went to a rheumatologist who discovered that I had psoriatic arthritis. This is an inflammatory arthritis and also an auto-immune disorder. My nails and my feet were the first target. The doctor then wondered whether the peripheral neuropathy was triggered in my feet and caused an inflammatory response that spread through my body. This would confirm the suggestions of a doctor-friend in Canada that it could possibly be mould disease that energised the inflammatory response through my body because of our house which had severe damp problems. My husband had to start taking chronic medication for his lungs during this time. This confirmed the possibility of mould disease as cause for the neuropathy.

In peripheral neuropathy a disease or injury of peripheral nerves may alter the fibres, and this sometimes results in a distortion of the response to an applied stimulus (Hodgson & Raff 2011:22). This leads to hyper excitability of the nerve fibres. It seemed that the psoriatic arthritis was the disease that caused the injury of nerves in my feet, and it was suggested that the mould exacerbated the inflammatory response in my body and caused the severe burning pain.

Neuropathic pain caused disability in my life and this led to altered mood states with despair and depression featuring high on the list of psychological effects (see Haanpää et al. 2011). It felt as if my whole body was in flames 24 h of the day. I battled to sleep and during the day I couldn't be who I wanted to be because the pain was stealing my memory and concentration. I couldn't play with the children who came for play therapy and I battled to listen to the adults telling me about their problems. I felt helpless and stupid, and most of the time I thought God was helpless as well. I often wondered why God was punishing me. I did my level best to be who I thought God wanted me to be. I often put other people ahead of my own needs and I couldn't understand why God was 'doing this to me'. I fully agree with the following words of Chetty (2012):

The burden of neuropathic pain for the patient is substantial. Neuropathic pain is associated with psychological distress, physical disability and reduced overall quality of life … (p. 5)

This pain was indeed 'the worst pain one could possibly imagine' (Pain Forum 2008:1)

The circuited path to the centre - God and people far … God and people near …

The labyrinth has a path that winds farther and nearer to the centre. One enters at the mouth far from the centre. I entered the labyrinth with Psalm 143:7 (The Message) going through my mind:

Hurry with your answer, God! I'm nearly at the end of my rope. Don't turn away; don't ignore me! That would be certain death.

As I walked I grappled with the following:

-

Loneliness - feelings of being cast aside - not part of the 'professional class'. This led to me becoming withdrawn and loosing intimacy with God and my loved ones.

-

I lost my professional identity … I realised my identity was built on what I do; my profession and ability to be there for others have disappeared. I no longer had the strength to listen to the problems of other people. My body was burning. I was in the hell of flames 24 h a day.

-

I tried to do what I could every day and I experienced that because I do not look ill, everyone thought I was doing fine. I felt misunderstood and alone.

-

The busy bee who has been there for all who needed me died. She was to be no more.

-

I often cried when my husband was asleep. I did not want to keep him awake with my pain. I could not sleep because the pain was excruciating. It was having a devastating effect on our marriage and our sex life.

-

I felt desperate at times and depression crept in. I often had suicidal thoughts.

-

Pain stole my joy and my peace.

-

Pain stole my life.

-

I was angry at times and wondered whether God really knew that I existed.

-

I read the Bible when I couldn't sleep … I read Job and the Psalms and I wondered what God was doing in my life.

-

Why was God angry with me and punishing me? What have I done wrong? Is there a way that I can make things right again and will the terrible pain subside then?

-

I wrote poems and long pieces in my journal.

Being diagnosed with a disease that causes intense chronic pain was the turning point in my personal spiritual journey. Questions like 'Where is God?', 'Is God punishing me?' and ideas like 'Maybe there is no God' were things that I struggled with. During the night when I couldn't sleep, I asked myself: How do I perceive God? Who is God? Who am I?

Is there such a thing as grace and mercy?

If this is what hell is, how do I stay serving God … a God who tortures?

Why is this happening to me?

Can I be angry with God? Is God testing my faith?

I read the Bible to try and find answers:

Psalm 6 (The Message)

Please, GOD, no more yelling,

no more trips to the woodshed.

Treat me nice for a change;

I'm so starved for affection.

Can't you see I'm black- and-blue,

Beat up badly in bones and soul?

I read all the psalms and when Gys, my husband, was awake with me, I would discuss my feelings and thoughts regarding the passages that I read with him. I often wondered whether it was right of me to be angry at God … whether my disappointment for not being healed would worsen the pain. Gys helped me to understand that in any relationship there is anger and disappointment. If there is a good relationship between me and God, my feelings of anger and disappointment are evidence of this relationship. He showed me where Jeremiah was feeling despair and that he actually told God what he was feeling.

Jeremiah 15:15-18 (The Message):

You know where I am, GOD! Remember what I'm doing here! …

Just look at the abuse I'm taking!

When your words showed up, I ate them -

Swallowed them whole. What a feast!

What delight I took in being yours,

O GOD, GOD-of-the-Angel-Armies!

I never joined the party crowd in their laughter and their fun.

Led by you, I went off by myself …

But why, why this chronic pain,

this ever worsening wound and no healing in sight?

You're nothing, GOD, but a mirage,

a lovely oasis in the distance - and then nothing!

This helped me to feel free to utter my own anger and disappointment. The circuit of the labyrinth turned to being closer to God for a little while.

Praying to a God I did not know … this was extremely difficult and resulted in more physical and emotional pain.

This is one of the poems I wrote during that time:

Pain, you win!

You invade me, so that Lishje disappears and becomes a bitch!

You change my being and steal my self-confidence.

You make me into someone that I don't want to be -

Someone who's spirit does not live with God's spirit

but with yóúrs … your angry, bitchy, burning personality!

I am a stranger in my own head and body.

You succeed in fooling me to forget that God loves me

and that it is God and not you who resides IN ME!

Writing poems and letters to God helped me to experience God with me. The last sentence in the poem above comforted me despite the angry voice of pain.

Just as I thought that I am now near the centre, where I believed that I can meet with God, the path turned back … People were easily giving their answers to my situation … Your belief is not strong enough … Your parents did something bad and did not repent … Satan is doing this … we have to send Satan away or get rid of Satan.

I met people who stressed the fact that God was indeed far and punishing me. A female minister came to pray for me. She said that I was not getting better because my faith was not strong enough. She also said that I am ill and experiencing severe pain because my parents did something very wrong in the eyes of God and they have not repented yet.

I then requested the elders to please come and pray for me. The men battled to pray. The prayer that stayed with me was the request that God must take the evilness away.

The discourse of God as the angry man who punishes when I am not doing what was expected was dominant. The other discourse that was stressed was that there was a devil that was controlling the pain in my body. These were dominant discourses that aggravated the feelings of despair, and it also worsened the pain.

I was devastated and with Jesus I yelled: 'God! Why have you forsaken me?!'

Luckily the winding path also went close to the centre. There were people who loved and cared for me. Gys, my husband, and Lize, my daughter, helped as much as they could. At times in the night when the pain was excruciating, Gys would hold my hands (he could not really touch me because of the hyper sensitivity of my body) and the tears would just roll down his cheeks. This saddened me because I did not want to burden him with my pain, but it also comforted me because I felt that he understood what I was going through. Later I learnt 'that those who witness pain in their partners demonstrate brain activity that is similar to actually experiencing pain' (Keefe, Somers & Kothaida 2009:40).

The path then made another turn towards the centre … One Sunday morning when I didn't go to church, there was a ring at the gate. I decided not to open as I was alone. Suddenly the gate opened and four cars drove in. Gys came in last. It was Reverend Koppin Dingaan from the Natalspruit Maranatha Reformed Church of Christ with the elders. They came to pray for me. This was an exceptional experience. I could not understand all the prayers but I felt the presence of God.

I was confronted with the fact that these people came because they heard about my illness. No one asked them to come. They just came! These were the people who were living the love of Jesus despite their own struggles with being poor and living under difficult circumstances. These African people came to our house to comfort me … the white 'MaMuruti' [wife of the Reverend]. I was astounded and the tears streamed down my face.

Unfortunately the path turned back again … I had two very good friends who worked in the corporate world. We would meet once every second or third week for coffee or a cocktail at a restaurant. We shared our worries and our lives. When I became so ill that I had to stop working, our relationship changed. Suddenly I would hear from them, 'you don't work anymore … you don't understand what it is like to work long hours with the stressors of the corporate world'. This had an immense impact on my self-esteem. I was confronted with the discourses of, 'your life only has meaning when you earn a good income', and 'you only have relevant knowledge when you are a career woman'. For the first time in my life I had a serious identity crisis. I also experienced that my life now had no meaning. I felt far from God and far from people.

I experienced feelings of abandonment and intense loneliness. I struggled to come to terms with who I have become. At times I was completely exhausted. I could not find peace in my situation.

Having intense feelings while one is walking the labyrinth may happen. According to Lauren Artress (2006:50) one should stay with these feelings: 'Once you begin to let your feelings flow, you are able to reflect upon your pain, confusion, and wounds from others'. I decided to stay with my feelings and reflect in my journal.

The questions I reflected on were:

-

What does your identity look like?

-

What formed your identity over the past years?

-

What would you like your identity to consist of?

These are some of the things that I wrote: Over the past years I had been a successful educational psychologist. I was a lecturer at the Rand Afrikaans University and I had a very good relationship with my clients and my students. The students that I accompanied in their master's dissertations all finished within the time frame, and most of them obtained high marks.

As I wrote this, I realised that my identity and my ego was one and the same thing. I was forced to ask myself where God is in this picture? This led to another turning point in my journey. I had to change the questions that I was asking God and myself.

I decided to not walk the path on my own. There were other women in the community who wanted to pray with me. I decided to make a call and ask for help. This helped to sustain my faith in a loving God. Lamentations 3:28-30 (The Message) spoke to me when I had my quiet time and I knew that there will be more help for my despair:

When life is heavy and hard to take, go off by yourself. Enter the silence. Bow in prayer. Don't ask questions: Wait for hope to appear. Don't run from trouble. Take it full-face. The 'worst' is never the worst.

Hope arrived in a woman who became 'Jesus incarnated' to me, Yolanda Dreyer. She visited me often and listened to my despair and struggles with God. She loved me and cared for me. She came whenever I needed someone to talk to. She showed me the love of God that was visible in the actions of Jesus. She also spoke to the congregation and taught them how to deal with my illness in a more appropriate way. Yolanda was 'doing hope' in a way that gave me hope to cope with the pain. Weingarten (2000:18) explains this as follows: Hope is something we do with others. Hope is too important - its effects on body and soul too significant to be left to individuals alone.

She explained to me that God is not angry with me. God is also not punishing me because of things my parents did. God is a loving God. Maybe we don't understand what is happening and why this illness with the severe pain is happening to my body, but what I must remember is that God is with me in my pain … just as God was there for Job, Jeremiah and Jesus. She reminded me that God was angry with Job's friends because they did not speak the truth about God (Job 42:7-8). In this journey with pain I had to choose whose voices I wanted to listen to. She helped me to remember other times in my life where I battled with difficulties and in the end I was assured of God's love for me.

In these times of struggle I came to know that I had an obsession with 'knowing and understanding'. I wanted to understand what God was doing in my life. I then came to realise that I wanted to be in control and '[t]o offer questions to God is to stop that obsession with knowing' (Johnson 1999:104). I was confronted with my beliefs about God. I discovered through conversation with Yolanda and reading different books that God was in me and talking to me through my body.

I learnt that accepting uncontrollability (perception of helplessness) may be less stressful than attempting to control an uncontrollable situation (Ogden 2004, in Pienaar 2010, 2/3:20). To change my attitude from 'I am helpless and have no control over the pain and its effects and therefore I can do nothing', to 'this is as it is and I can still do something', made a big difference in the way I functioned every day.

During this time a woman I didn't really know brought me a book that has helped her to cope with cancer and the pain she experienced: The Healer Inside by David Patient and Neil Orr. While I was reading the book, I realised that I have to accept the pain and take the responsibility for my thoughts. This was the introduction to Psychoneuroimmunology. I learnt that I had to be kind and grateful towards my body. This article does not have the scope to write about everything this entails (cf. Pienaar 2010, 2/3:13-20). It helped me to make a definite turn towards the centre of the labyrinth.

I learnt that my questions had to change to 'What do you want me to do in this situation God? How can you use me despite the pain?' I learnt that to ask 'Why is this happening?' had no answer; I had to think differently about my situation and God (see Deist 1985).

Kaethe Weingarten was another woman who played a significant role in my learning process to accept and live with chronic pain. I met with her in Somerset West after attending a course that she presented. She taught me the difference between rainbow hope and reasonable hope.

Rainbow hope is consistent with a dominant religious discourse that says praying and believing strongly enough will heal the disease and give back one's health. It causes unrealistic hope, which leads to more feelings of distress when life does not happen that way. Fundamentalist approaches to the Bible lead to the belief in rainbow hope.

Reasonable hope is more sensible as it accepts risks and uncertainty. Weingarten (2010) states this as follows:

Reasonable hope, consistent with the meaning of the modifier, suggests something both sensible and moderate, directing our attention to what is within reach more than what may be desired but unattainable. (p. 7)

This session helped me to focus on things that I can do instead of concentrating on the pain and the different aspects of loss that accompanied the pain.

The sessions with Yolanda helped me to realise that God is with me in my pain. The other people who cared and prayed and listened helped me to realise that this journey in pain is not a lone journey …

Doing reasonable hope helped me to make sense of what was happening in the here and now and helped me to make plans for the future. By showing empathy and understanding, the people in this part of my journey showed me that God is not punishing me. God is with me in my everyday struggling. With hope I could enter the centre of the labyrinth.

I started to experience a change in my spirit and in my coping skills, but when there were a lot of stressors the pain caught up again. My back started giving problems again and my body was burning. I was sent for nuclear x-rays. When I went back to the neurosurgeon he sent me to an orthopaedic surgeon with the words, 'I have never seen feet this bad. Your back is okay'. The orthopaedic surgeon said that there is nothing that he can do. I have to get off my feet or otherwise in a few years' time I would not be able to walk. This was a blow to everything that I have planned and decided and again the path in the labyrinth turned away from the centre.

I decided that I needed a break and also that I needed a therapist again. I flew to Cape Town to stay with my 'daughter from another mother' for a week and made appointments to see the man who helped me with emotional problems when we lived in Port-Elizabeth and was now residing in Bellville.

My visit to Cape Town was my final turning point. I asked to be left alone and I spent many hours gazing at the sea. I saw the therapist who asked me to think about my life and what I still wanted to do and achieve. These questions took me back to the identity crisis that I experienced before. I left him with a knot on my stomach and again I wondered whether my life had any sense …

The next morning I strolled down to the beach and I sat on the sand and watched the waves crashing on the rocks. I wondered whether I came to Cape Town to finally realise that the life I hoped for was not going to become reality. If I had to stay off my feet, I would not be able to do the house work, run the women's weekends, play with the children or sing in the church band. I would not be able to do shopping the way that I was used to … I would become more dependent on other people for help. All these thoughts created havoc in me and once again I wondered whether I shouldn't just walk into the sea like Ingrid Jonker did.

As I sat there, watching how murky the water has become, I saw a Cape Cormorant in the waves. Then it was as if I heard God's voice speaking in my head.

'Lishje, do you see the Cormorant? Watch what it is doing …'. I saw the bird watching the waves and then sometimes it moved to the left and other times it dived underneath the waves. It went on like this until it reached the lovely blue water. Then I heard the voice again:

You can now choose … You can either be like this Cormorant and plan which of the 'waves' of your illness you want to face and which ones you want to swim away from; or, you can be like the Seagulls and yell about the life you have to live.

At that moment a flock of seagulls flew over my head, 'yelling!' Furthermore, I heard:

Do you see this ocean that this Cormorant is in? That is me, your God. You can choose whether you want to trust and be with me like I am with you or whether you want to turn away and keep on yelling.

This experience was the most amazing thing that has ever happened to me. It also was the final turning point to the centre of the labyrinth. My questions changed to: What kind of person do you want to be now? How can you be of help to other people who are also suffering with physical pain?

Being in the centre of the labyrinth

Discovering contemplative spirituality and becoming more contemplative myself added to my personal journey. Walking a labyrinth with the purpose of connecting with God who lives in me became part of choosing to live differently.

I discovered in the words of Trevor Hudson (2007) that '… the Divine Voice causes [my] heart to burn with renewed faith and hope' and I too discovered that understanding this quiet voice in my heart led me to a 'more generous love of God and other people, and a proper love of [myself] as beloved of God' (p. 35). I also learnt that the words of Mother Teresa (2016) are true: If we really want to pray, we must first learn to listen, for in the silence of the heart, God speaks. This is what happened to me on the beach. I stopped questioning God and just sat … and God spoke!

Except for my husband, the people who co-created hope with me were mostly women. This reminded me that it was also mostly women who were at the cross of Jesus in his deepest despair and it was the same women who were there when the grave was empty. The last witnesses of Jesus' suffering became the first witnesses of the resurrection. The following quote by Osiek (1997:116) states the role of the women in Jesus' life and in my life clearly: 'The women disciples who followed Jesus from Galilee to Jerusalem, even to his death on a cross, faithfully performed their diakonia of service, witness, and representation' (Mk 15:40-41; Mt 27: 55-56; Lk 8:1-3; 24:10).

When I arrived in the centre of the labyrinth, I realised that the power of the resurrection - the transformation of my life - was God's gift to me. I realised that God walked the journey with me … The power of our victory went through the journey with suffering. God lives inside of me and through the cracks in my life the everlasting LIGHT shines - now and forever.

I made a decision to be there for people suffering. I joined PAINSA and did a course on pain, the effects and treatment thereof. I started a support group and am still running it. I also decided that I am accepting the situation as it is and I know God is with me because God lives in me. I changed my way of life to a more contemplative way of living. I learnt that breathing, meditation and mindfulness do not cure the illness, but it surely helps me to cope with the pain in a more healthy and appropriate way. The following words of Richard Rohr (Center for Action and Contemplation Daily Meditation) speak loud and clear:

We must die before we die. Suffering - whenever we are not in control - is the most effective way to destabilize and reveal our arrogance, our separateness, and our lack of compassion. If we do not transform our pain, we will most assuredly transmit it.

Walking out

With a grateful heart I am still on my journey. Gys and Yolanda showed me what the compassion of Jesus means practically. They loved me enough to confront me at times when my ego and will to control were too strong and hampered my healing. I learnt that healing is often not physical but spiritual and that this kind of healing is what I actually needed. I also learnt that my identity comes from within where God and I live together.

I also learnt that the faith community finds it difficult to deal with problems and illness - especially when it resides in the home of the minister. They had to be taught how to deal with it. Furthermore, I now know that the church as institution often stays with the discourses that make the ministers and the managing team comfortable. The comfort zone of the institution lies within the discourses that teach a God who judges. Heaven and hell still play a dominant role in this discourse. I do not adhere to these discourses any longer.

I experienced the love and compassion of Jesus mostly outside the formal church situation with people who would just be with me. The prayers of the official church people, the ministers and the elders scared me and were not helpful. This confirms my belief that the institution and the managers of the institution will keep living and preaching the discourse of an unloving God. Judging and deciding what God 'wants' and 'needs' are still important elements in the religion of the Dutch Reformed and the Netherdutch reformed Church. This leads to a religion that is exclusive in nature. I strongly believe that this is not what God wants and what Jesus taught.

I agree with the following words of Catherine LaCugna (In Rohr Daily Meditation 03 March 2017): 'The nature of the church should manifest the nature of God …'.

I found peace in my being with God. Meditating and praying brought me to a safe place where I do not have to perform any longer. My identity is in God. I am living my life with the words of Carolyn Myss (2007:235): 'Surrender and let God reorder the flow of your life. You are re-entering your life … soul first'.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that she has no financial or personal relationships which may have inappropriately influenced her in writing this article.

References

Aldridge, A., 2007, Religion in the contemporary world, Polity, New York. [ Links ]

Anderson, H. & Goolishian, H., 1992, 'The client is the expert: A not-knowing approach to therapy', in S. McNamee & K.J. Gergen (eds.), Therapy as social construction, pp. 29-35, London, Sage. [ Links ]

Artress, L., 2006, The sacred Path companion. A guide to walking the labyrinth to heal and transform, The Berkley Publishing Group, New York. [ Links ]

Bainham, A., Sclater, S.D., & Richards, M., 2002, Body lore and laws: Essays on law and the human body, Bloomsbury Publishing, London. [ Links ]

Berendes, D., Keefe, F.J., Somers, T., Kathadia, S.M., Porter, L.S. & Cheavens, J., 2010, 'Hope in the context of lung cancer: Relationships of hope to symptoms and psychological distress', Journal of pain and Symptom Management 40(2), 174-182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.01.014 [ Links ]

Bloos, I.D., 2002, 'Ancient and medieval labyrinth and contemporary therapy: How do they fit?', Pastoral Psychology 50(4), 219-230. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014097211429 [ Links ]

Bolak, H.C., 1997, 'Studying one's own in the middle east: Negotiating gender and self-other. Dynamics in the field', in R. Hertz (ed.), Reflexivity and voice, pp. 95-118, Sage, London. [ Links ]

Borg, M.J., 1997, The God we never knew. Beyond dogmatic religion to a more authentic contemporary faith, Harper, San Francisco, CA. [ Links ]

Borg, M.J., 2000, 'My faith', viewed 24 February 2017, from http://www.explorefaith.org/faces/my_faith/borg/moving_beyond_self-judgment.php. [ Links ]\

Buechner, F., 1983, Now and then: A memoir of vocation, Harper & Row, New York. [ Links ]

Burr, V., 1995, An introduction to social construction, Routledge, London. [ Links ]

Charmaz, K. & Mitchell, R.G. (jnr.), 1997, 'The myth of silent authorship: Self, substance and style in ethnographic writing', in R. Hertz (ed.), Reflexivity and voice, pp. 193-215, Sage, London. [ Links ]

Chetty, S., Baalbergen, E., Bhigjee, A.I., Kamerman, P., Ouma, J. & Raath, R., 2012, 'Clinical practice guidelines for management of neuropathic pain: Expert panel recommendations for South Africa', Journal of Painsa 7(2), 5-19. https://doi.org/10.7196/samj.5472 [ Links ]

Clauw, D.L.J., 2014, 'Fibromyalgia', JAMA 311(15), 1547-1555. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.3266 [ Links ]

Connely, D.K., 2005, 'At the center of the world: The labyrinth pavement of Chartres Cathedral', in S. Blick & R. Tekippe (eds.), Art and architecture of late medieval pilgrimage in Northern Europe and the British Isles texts, pp. 285-314, illus. pp. 134-148, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Comenius, J.A., 1631, 'The labyrinth of the world and Paradise of the heart revised, text of James Naughton from 2004-2005', viewed 20 January 2017, from http://www.labyrint.cz/ [ Links ]

Custer, D., 2014, 'Autoethnography as a transformative research method', The Qualitative Report 19(37), 1-13, viewed 9 December 2016, from http://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol19/iss37/3 [ Links ]

Davies, B., 1991, 'The concept of agency: A feminist poststructuralist analyses', Postmodern Critical Theorising 40, 42-53. [ Links ]

De Vault, M.L., 1997, 'Personal writing in social research: Issues of production and interpretation', in R. Hertz (ed.), Reflexivity and voice, pp. 216-228, Sage, London. [ Links ]

Deist, F., 1985, Waarom God? Aantekeninge by Lyding, CUM-Boeke, Helderkruin, Roodepoort. [ Links ]

Dreyer, Y., 2003a, 'n Teoretiese inleiding tot narratiewe hermeneutiek in die teologie', HTS Theological/Teologiese Studies 59(2), 313-323. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v59i2.663 [ Links ]

Dreyer, Y., 2003b, 'Luister na die storie van die kerk: Riglyne vanuit 'n narratief-hermeneutiese perspektief', HTS Theological/Teologiese Studies 59(2), 333-352. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v59i2.663 [ Links ]

Dreyer, Y., 2016, 'Reframing youth: A narrative and the dream of a South African idol', Pastoral Psychology 65, 643-655. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-016-0691-7 [ Links ]

Durkheim, E., 1915, The elementary forms of the religious life: A study in religious sociology, transl. J.W. Swain, George Allen & Unwin, London, viewed 20 March 2017, from https://archive.org/…/elementaryformso00durkrich/elementaryformso00durkrich_djv [ Links ]

Dworkin, R.H., O'Connor, A.B., Backonja, M., Farrar, J.T., Finnerup, N.B. & Jensen, T.S., 2007, 'Pharmacologic management of neuropathic pain: Evidence-based recommendations', Pain 132, 237-251, in Journal of Pain SA, The South African Chapter of the IASP 3(3), 15-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2007.08.033 [ Links ]

Ellis, C., 2002, 'Being real: Moving inward toward social change', International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 15(4), 399-406. [ Links ]

Els, L., 2000, 'The co-construction of a preferred therapist self of the educational psychologist', Unpublished D.Ed. thesis, Department of Education, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Fedler, C., 2010, 'HIV/AIDS associated pain: Causes and management principles', The Specialist Forum 4, 55-68. [ Links ]

Ferré, R., 2000, 'Foreword', in J.K.H. Geoffrion (ed.), Living the labyrinth. 101 paths to a deeper connection with the sacred, pp. xi-xii, The Pilgrim Press, Cleveland, OH. [ Links ]

Foucault, M., 1972, Archaeology of knowledge, transl. A.M. Sherdian-Smith translation, Tavistock, London. [ Links ]

Foucault, M., 1980, Power/knowledge: Selected interviews, 1972-1977, transl. C. Gordon, Pantheon, New York. [ Links ]

Fulbright, A., 2010, 'The way home: The theology of Marcus Borg', viewed 20 February 2017, from http://uuroanoke.org/sermon/091115Borg.htm [ Links ]

Giorgio, G., 2009, 'Traumatic truths and the gift of telling', Qualitative Inquiry 15(1), 149-167. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800408318300 [ Links ]

Geoffrion, J.K.H. (ed.), Living the Labyrinth. 101 paths to a deeper connection with the sacred, The Pilgrim Press, Cleveland, OH. [ Links ]

Glombiewski, J.A., Sawyer, A.T., Gutermann, J., Koenig, K., Rief, W. & Hofmann, S.G., 2011, 'Psychological treatments for fibromyalgia: A meta-analysis', Journal of Pain SA, The South African Chapter of the IASP 6(2), 25-39. [ Links ]

Haanpää, M., Attal, N., Backonja, M., Baron, R., Bennet, M. & Bouhassira, D., 2011, 'NeuPSIG guidelines on neuropathic pain assessment', Pain 152, 14-27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2010.07.031 [ Links ]

Heo, H., 2004, 'Storytelling and retelling as narrative inquiry in cyber learning environments', in R. Atkinson, C. McBeath, D. Jonas-Dwyer & R. Phillips (eds.), Beyond the comfort zone: Proceedings of the 21st ASCILITE Conference, pp. 374-378, Perth. http://www.ascilite.org.au/conferences/perth04/procs/heo.html [ Links ]

Hertz, R. (ed.), 1997, Reflexivity and voice, Sage, London. [ Links ]

History of the Labyrinth, viewed 12 December 2016, from https://www.theosophical.org/publications/1276; [ Links ] Project Labyrinth of the World www.labyrinth.cz; www.labyrinthbuilders.co.uk/about_labyrinths/history.html [ Links ]

Hodgson, E. & Raff, M., 2011, 'Diagnosis and management of neuropathic pain', Journal of Pain SA 6(3), 22-25. [ Links ]

Hudson, T., 2007, Invitations to abundant life. In search of life at its best, Struik Christian Books, Cape Town. [ Links ]

James, J., 1977, 'The mystery of the great labyrinth, Chartres Cathedral', Studies in Comparative Religion 11(2), viewed 6 March 2017, from World Wisdom, Inc., www.studiesincomparativereligion.com [ Links ]

Jeanes, R., 1979, 'Labyrinths', Parabola 4(2), 12-15. [ Links ]

Johnson, J., 1999, When the soul listens: Finding rest and direction in contemplative prayer, Tyndale House Publishers, Carol Stream, IL. [ Links ]

Jones, S.H., Adams, T.E. & Ellis, C., 2013, Handbook of autoethnography, Left Coast Press, Walnut Creek, CA. [ Links ]

Keefe, F.J., Somers, T.J. & Kothadia, S.M., 2009, 'Clinical updates: Coping with pain', International Association for the Study of Pain XVII(5), Painsa 2010, 5(2), 38-40. [ Links ]

Kotzé, E. & Kotzé, D.J., 1997, 'Social construction as a postmodern discourse: An epistemology for conversational therapeutic practice', Acta Theologica 1, 27-50. [ Links ]

Langer, S., 2012, 'The difference between metaphors and symbols', Sceptical Prophet, viewed 6 march 2017, from https://scepticalprophet.wordpress.com/2012/10/22/the-difference-between-metaphors-and-symbols/ [ Links ]

Lather, P., 1991, Getting smart: Feminist research and pedagogy within the postmodern, Routledge, New York. [ Links ]

Mother Teresa, 2016, 'In the silence of the heart', viewed 7 March 2017, from http://www.goodreads.com/quotes/252954-in-the-silence-of-the-heart-god-speaks-if-you. [ Links ]

Mills, S., 1997, Discourse, Routledge, London. [ Links ]

Myss, C., 2007, Entering the castle. An inner path to God and your soul, Simon & Schuster, Ltd, London. [ Links ]

Orr, N.M. & Patient, D., 2004, The healer inside you: Using PNI, a mind-body science, to help heal your body, Juta and Company, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Osiek, C., 1997, 'The women at the tomb: What are they doing there?', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 53(1 & 2), 103-118. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v53i1/2.1600 [ Links ]

Pain Forum, 2008, 'Understanding neuropathic pain - Clinical presentation and underlying pathophysiology and targets of drug therapy', The Specialist Forum, February, pp. 1-2. [ Links ]

Parker, I., 1989, 'Discourse and power', in J. Shotter & K.J. Gergen (eds.), Texts of identity, pp. 56-69, Sage, London. [ Links ]

Patient, D. & Orr, N., 2004, The healer inside you, Double Story Books, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Pienaar, M., 2010, 'Introduction to psychoneuroimmunology', Journal of Pain SA 2(3), 13-20. [ Links ]

Reed, D.P., 1990, The idea of the labyrinth: From classical antiquity through the middle ages, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY. [ Links ]

Reinharz, S., 1992, Feminist methods in social research, Oxford University Press, New York. [ Links ]

Rohr, R., 2017, 'Daily meditations archive - Center for Action and Contemplation, 31 January 2017', viewed 5 March 2017, from https://cac.org/richard-rohr/daily-meditations/daily-meditations-archive. [ Links ]

Saddington, J.A., 1992, 'Learner experience: A rich resource for learning', in J. Mulligan & C. Griffen (eds.), Empowerment through experiential learning: Explorations of good practice, pp. 37-49, Kogan Page, London. [ Links ]

Saward, J.A., 'Brief history of the Labyrinth', viewed 12 December 2016, from www.labyrinthbuilders.co.uk/about_labyrinths/history.html [ Links ]

Schaper, D. & Camp, C.A., 2012, Labyrinths from the outside in. Walking to spiritual insight. A beginner's guide, Sky Light Paths, LongHill Publishers, Woodstock. [ Links ]

Schutte, P.J.W., 2016, 'Workplace spirituality: A tool or a trend?', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 72(4), a3294. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v72i4.3294 [ Links ]

Sclater, S.D., 2003, 'What is the subject?', Narrative Inquiry 13(2), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1075/ni.13.2.05day [ Links ]

Smith, D.E., 1992, 'Sociology from women's experience: A reaffirmation', Sociological Theory 10(1), 88-98. https://doi.org/10.2307/202020 [ Links ]

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), [1994] 2012, 'Classification of chronic pain', in H. Merskey & N. Bogduk (eds.), IASP Task Force on Taxonomy, Washington, DC, viewed 10 December 2016, from http://www.webmd.com/pain-management/guide/understanding-pain-management-chronic-pain [ Links ]

Ward, G., 2006, Spirals. The Pattern of Existence, Green Magic. Long Barn Sutton Mallet TA 9 AR, England. [ Links ]

Weingarten, K., 1997, The mother's voice: Strengthening intimacy in families, Gilford, New York. [ Links ]

Weingarten, K., 2000, 'Witnessing, wonder and hope', paper presented at the 8th International Conference of the South African Association of Marital and Family Therapy, Cape Town, South Africa, 5-8 April. [ Links ]

Weingarten, K., 2010, 'Reasonable hope: Construct, clinical applications, and supports', Family Process 49(1). 5-25 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2010.01305.x [ Links ]

White, M., 1991, 'Deconstruction and therapy', Dulwich Centre Newsletter (Adelaide), 3, 1-22. [ Links ]

White, M., 1997, Narratives of therapist's lives, Dulwich Centre Publications, Adelaide. [ Links ]

Zautra, A.J., Fasman, R., Parish, B.P., & Davis, M.C., 2007, 'Daily fatigue in women with osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and fibromyalgia', Pain 128, 128-135, Journal of Pain SA, The South African Chapter of the IASP 2(2), 37-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.004 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Lishje Els

lishje.els@gmail.com

Received: 03 Apr. 2017

Accepted: 26 Apr. 2017

Published: 23 June 2017

Project Leader: Y. Dreyer

Project Number: 2546930

Dr Lishje Els is participating in the research project, 'Gender Studies and Practical Theology Theory Formation', directed by Prof. Dr Yolanda Dreyer, Department of Practical Theology, Faculty of Theology, University of Pretoria

1 Cf. inter alia Glombiewski; Sawyer; Gutermann; Koenig, Rief; Hofmann - referred to in the journal Painsa, 2011 pp. 25-39). See also Zautra; Fasman; Parish; Davis - referred to in the journal Painsa, 2006, pp. 37-45).