Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

HTS Theological Studies

On-line version ISSN 2072-8050

Print version ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.73 n.3 Pretoria 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v73i3.3421

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Conceptualising holiness in the Gospel of John: The mode and objectives of holiness (part 1)

Dirk van der Merwe

Department of Christian Spirituality, Church History and Missiology, University of South Africa, South Africa

ABSTRACT

This article investigates the code of holiness as well as the objectives of holiness in the Gospel of John. The en route to holiness will be dealt with in a following article, 'Conceptualizing holiness in the Gospel of John: the en route to holiness and the character of holiness (Part 2)'. In the Gospel of John, the holiness of the trinity constitutes the theological environment for the code of holiness and forms the basis for the exhortation to holiness. The code of holiness is described in the light of the interaction of three levels of relationships: the unity between Father and the Son as the example of holiness, the unity between Jesus and the disciples as the basis for holiness and the unity among the disciples as the inducting objective for holiness. For the Fourth Evangelist, the objective of holiness is fourfold: The first objective is to constitute a unity among the followers of Jesus (17:20-23), although it is not explicitly defined in this context. The second objective refers to the preparation of Jesus' disciples to continue Jesus' mission. The third objective for holiness is that the world (ὁ κόσμος) may believe (πιστεύῃ) and may know (γινώσκῃ) that God has sent his Son (ὅτι σύ με ἀπέστειλας) (17:20-23). The fourth and the ultimate objective is the glorification of God (17:4).

Introduction

Interest in the theme of holiness or spiritual growth in Christianity has grown over the past few decades owing to the emergence of, and interest in, Christian spirituality1 and Christian mysticism. This interest is observed in the many publications on spirituality, mysticism, holiness, devotion and discipleship, which all relate to holiness. This article investigates how holiness is expressed in the Gospel of John.

The Dictionary of New Testament Theology (Brown 1976:223) identifies three different adjectives2 in the Greek language that denote 'holy': ι ̔ ε ρός, ὅσιος and ἅγιος. The first adjective, ι ̔ ερο ́ ς, 'denotes the essentially holy, the taboo, the divine power or what was consecrated to it, for example, sanctuary, sacrifice, priest' (Brown 1976:223). In Brown's (1976:235) explanation of the meanings of the New Testament usage of this adjective, only three references are relevant. It denotes a holy person or thing, 'worthy of reverence' (ἱεροπρεπεῖς, cf. Tt 2:3). Paul uses this adjective ([τά] ἱερά, sacred, holy) in 2 Timothy 3:15 in reference to the sacred writings. The last reference is found in 1 Corinthians 9:13, where Paul uses τά ἱερά in the usual sense of sacred actions. Paul also uses the verb ἱερουργοῦντα (to perform sacred rites) in Romans 15:16 to give correct instruction about offering sacrifices. The definition given by Arndt, Danker and Bauer (2000:470) relates to that of Brown: (1) 'being of transcendent purity, holy' and (2) 'belonging to the temple and its service, holy thing'. In their semantic dictionary, Louw and Nida (1996:I, 532, 53.9), influenced by 1 Corinthians 9:13, define ἱερά briefly as 'something which has been dedicated exclusively to the service of God'.3

Another adjective is ὅσιος, which is used only eight times in the New Testament. According to Brown (1976:223), ὅσιος indicates 'divine commandment and providence' as well as 'human obligation and morality'. Zodhiates (2000:#3741) explains that the adjective ὅσιος means '[h]oly, righteous, unpolluted with wickedness, right as conformed to God and his laws'.4 According to Zodiates (2000), ὅσιος is similar to the Hebrew adjective דיִסָח ('kind, pious, so, as denoting active practice of דֶסֶח, kindness' [Brown, Driver & Briggs 2000:339]). This denotes that the person is willingly to accept requirements which arise from the covenant relationship with God. Such a person is called 'the loyal, the pious one'. In the New Testament, ὅσιος refers to 'God, as the personification of holiness and purity' (Rv 15:4; 16:5; in the LXX, Dt 32:4; Ps 145:17). With regard to humans, it refers to pious or godly people, those who are careful in all duties towards God (Tt 1:8). With regard to Christ (see Heb 7:26; Ac 2:27 and 13:35), it refers to his incorruptible body (Zodhiates 2000:#3741).5

The last term is the adjective ἅγιος, which is the most frequently used word group of the three discussed here. Brown (1976:223) interprets it ethically and emphasises that 'the duty to worship the holy' is the main principle embedded in the word. In consequence, two facts are fundamental here: The first fact relates to the trinity, which is referred to as being holy. God is denoted as holy (ἅγιος, Jn 17:11; 1 Pt 1:15f.; Rv 4:8; 6:10). Jesus is also called holy (Jn 6:69; Rv 3:7; cf. 1 Jn 2:20). The Spirit is referred to as the Holy Spirit, and the concept of spiritual growth and/or holiness is connected to the Holy Spirit. The second fact relates to the sphere of holiness. In the New Testament, the cult is no longer the sphere of holiness - the sphere of holiness is the prophetic expression of the Gospel. The sacred is no longer connected to things, places or rites, as in the Old Testament. It is now connected 'to the manifestation of life produced by the [Holy] Spirit' (Brown 1976:228).

Arndt et al. (2000:10) define ἅγιος as 'being dedicated or consecrated to the service of God'. The fundamental idea of this adjective is 'separation, consecration, devotion to the service of Deity', and also sharing in the purity of God and abstaining from the defilement of the world (Zodhiates 2000:40). Thus, while ἱἱερός indicates what has been consecrated and ὅσιος refers to purity and/or incorruptibility, ἅγιος denotes devotion to service.

In the Gospel of John, only the adjective ἅγιος and the verb ἁγιάζω appear. The adjective, ἅγιος, is used five times (1:33; 6:69; 14:26; 17:11; 20:22) and the verb, ἁγιάζω, four times (10:36; 17:17, 19[bis]). These occurrences constitute the theological environment in which holiness is to be interpreted and understood. This article6 firstly explores the theological environment of holiness in the Gospel of John. Secondly, it investigates the code of holiness and lastly the objectives for holiness in the Gospel of John.

Theological environment of holiness in the Gospel of John

• All the adjectives (ἅγιος) refer to the holiness of the trinity (Father, 17:11; Son, 6:69; Spirit, 1:33, 14:26 and 20:22). The verbs are connected to the mission of Jesus (10:36; 17:19) and the continuation of Jesus' mission by his disciples (17:17).7 These texts are now briefly examined.

The adjective ἅγιος

'Holy Father' (πάτερ ἅγιε, 17:11)

The only reference to God as Holy Father in the Gospel of John (17:11) has to be interpreted in the light of two phrases (see italics) in the verse, 'Holy Father, protect them in your name that you have given me, so that they may be one, as we are one'. The imperative (τήρησον, 'protect') is followed by a ἵνα-clause, ἵνα ὦσιν ἓν καθὼς ἡμεῖς ('so that they may be one , as we are one').

• 'Holy Father'8: Keener (2003b:1057) points out that 'Holy Father' (πάτερ ἅγιε) is expected in this context as it would be in an early Jewish milieu.9 In the Old Testament, God is also called 'the Holy One' (of Israel), and God is addressed as holy in the Jewish prayers: 'O holy One, Lord of all holiness' (II Macc xiv 36)10; 'O Lord, Lord, King of the heavens, and Ruler of the whole creation, Holy among the holy' (III Macc 2:2).11 A Eucharistic prayer found in Didache ix-x refers to God as 'holy Father': 'We thank Thee, holy Father, for Thy holy name'12 (cf. Brown 1972:II, 759). Zimmerli (1978:142) is of the opinion that Yahweh, who approaches his children, wishes his nature (שׁוֹ֔דָק, holy) to be reflected in theirs. This point is 'clear in the statement that introduces the core of the legal material in the Holiness Code: 'You shall be holy, because I, Yahweh your God, am holy' (שׁוֹ֔דָק, Lv 19:2; also 1 Pt 1:16). For Zimmerli (1978), the closeness between the gift of Yahweh and his commandment is definite.13 Keener (2003b:1057) adds to Zimmerli's argument by stating that 'God is the measure of holiness14 (cf. Rv 4:8), and whatever is 'holy' is 'separated' to Him'. Consequently, this reference to God as 'Holy Father' prepares the way for 17:17-19: the sanctification and consecration of the disciples (17:17) and Jesus (17:19) (Carson 1991:561).

• Protect them in your name: Jesus 'protected' his disciples from the world with the name of God (17:11), in this literary context, 'Holy Father'. According to Keener (2003b:1057; also Brown 1972:II, 759), the preposition ἐν ('in') can be both locative and instrumental: the disciples who are in the world are protected 'in the name of God' and simultaneously God protects them by means of his name.15 The Father will continue to set the disciples apart from the world as Jesus has separated them from the World (17:12).16 For Borchert (2002:197), the awesomeness and power of God embedded in 'Holy Father' provide a sense of security when the disciples need to face the hostile world. The holiness of the disciples will become their unique and transforming characteristic in the world (17:17).

• They may be one: Throughout this prayer (Jn 17), the overarching concern is mission (Borchert 2002:197). Separation from the world generates internal communion and cohesion. The idea here is that mutual unity with the 'Holy Father' and the Son ('the Holy One of God', 6:69) yields unity among the followers of Jesus (cf. 17:21-23) and enables them to continue Jesus' mission so that the world may believe and know the Father has sent his Son.

'The Holy One of God' (ὁ ἅγιος τοῦ θεοῦ, 6:69)

Peter's Christological confession that Jesus is 'the Holy One of God'17 occurs in a situation where Jesus asks his disciples if they also want to leave him, as many of the other disciples have (6:67). Beasley-Murray (2002:97) states that the term 'holy' in this context refers to that which belongs to God. He was influenced by Bultman's (1971:449) interpretation that 'Jesus stands over against the world simply as the One who comes from the other world and belongs to God … he is the Holy One of God'. Carson (1991:304) equates the adjective 'holy' used to describe Jesus with the adjective in 'Holy Father'.

For Peter to confess that Jesus is the 'Holy One of God' is a faith response to Jesus' utterance in 6:21: 'I am'. Within the context of the entire Gospel, the confession 'Holy One of God', who has been consecrated by the Father and sent into the world (10:36) with a specific mission, is the culmination point of his God-ordained mission (cf. Beasley-Murray 2002:97).

With the confession of Peter, the Evangelist replaces the 'Christ' confession of the Markan tradition (Mk 8:29) and the 'Son of the living God' in Matthew 16:16, referring to Jesus as the 'Holy One of God'18 (see 3:31-34; 10:36; also cf. Ac 3:14; Rv 3:7).19 For Brown (1975:298; also Carson 1991:304), the closest parallel to these references in the Gospel of John is 10:36, where Jesus speaks of himself as 'the one whom the Father has sanctified (ἡγίασεν, make holy)'. Before Jesus and his disciples go to Gethsemane where Jesus is captured, he says to his disciples, 'I sanctify (make holy) myself' (17:19).20 This can indirectly relate to Jesus' statements that he speaks the words of God, does the works the Father has shown him and endeavours to do the will of the Father.21 If so, then it relates to his God-ordained mission.

The Holy Spirit (πνεύματι ἁγίῳ, 1:33; 14:26; 20:22)

The expression 'Holy Spirit' is found in each of the major sections (1:19-12:50; 13:1-17:26 and 18:1-21:25) of the Gospel: 1:33; 14:26; 20:22 (Koester 2008:134; also Keener 2003a:458). The most significant of the three texts is 1:32-3:32 'I saw the Spirit descending from heaven … and it remained on him (ἔμεινεν ἐπʼ αὐτόόν).33 … He on whom you see the Spirit descend and remain (μένον) is the one who baptizes with the Holy Spirit'.22 This term ἔμεινεν is used elsewhere in the Gospel to denote 'mutual indwelling and continuous habitation' (e.g. 14:25, μένων)23 (cf. Keener 2003a:460).

The verse identifies the Spirit as God's Spirit. More meaning than the historical Baptist is probably intended is embedded in the designation 'the Holy Spirit'. 'What the Evangelist is saying is that "the coming one" will inaugurate the age of God's salvation when God's Spirit will purify mankind' (Newman & Nida 1993:39). This reference to the 'Holy Spirit' in 1:33 implies that Jesus (and his disciples) are sealed with a divine mark. As the Baptist could recognise Jesus by the descending and indwelling of the Spirit, so could his followers be recognised as anointed by God by their indwelling of the Spirit (Keener 2003a:461).

In 14:26, the 'Holy Spirit' is identified as the Paraclete:24 'But the Helper, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in my name …'. The Father sends the Spirit (14:16), although Jesus also sends the Spirit (15:26; 16:7). The position of this verse in the Gospel points out that the mission of Jesus is on the brink of fulfilment and will soon be completed. The work that the Holy Spirit has to come and do, as the other Paraclete, is to continue Jesus' mission. Although the Holy Spirit continues the mission of Jesus, Jesus remains the patron of that work in his heavenly mode of existence (Ridderbos 1997:510). The Spirit was never intended to replace Jesus. He ratifies the continuing presence of Jesus (cf. 14:17) and his involvement with the mission of the disciples (Neyrey 2007:249). 'The Paraclete makes possible, continued access to Jesus after Jesus has departed … In the Discourses Jesus' exclusive ability to provide a way to the Father is strongly reasserted, and the Paraclete is depicted as providing the believers with continual access to Jesus' (Brown 2003:22). For Neyrey (2007:249), the sole function of the Paraclete is to keep Jesus present to his disciples:25 '… the Helper, the Holy Spirit … will teach you everything, and remind you of all that I have said to you' (14:26). The Spirit has no message of its own26: '… for he will not speak on his own, but will speak whatever he hears …' (16:13b-14).

The third and last reference to the Holy Spirit is found when Jesus 'breathed27 on them and said to them, "Receive the Holy Spirit"' (20:22). This verse combines two central aspects of the work of the Spirit according to John: purification and/or rebirth and empowerment for ministry to continue the mission of Jesus (cf. Westcott & Westcott 1908:350-1). Through Jesus, a new humanity or new creation is brought forth. It seems possible that the Evangelist brings to mind here 'the regenerating aspect of the Spirit of purification' (Keener 2003b:1204-1205). Another explicit and crucial aspect in this text is the prophetic anointing to proclaim the Gospel message which relates closely to 1:33, when the Holy Spirit descends on Jesus to abide in him. Before Jesus gives his disciples a mandate to receive the 'Holy Spirit',28 he commissions them to carry on his own mission (20:21). Here, the missions of Jesus and his disciples are explicitly connected with the outpouring of the 'Holy' Spirit.

From these three texts, it is evident that the 'Holy' Spirit is (1) the divine mark of anointment, indwelling and empowerment (1:33), (2) the one who keeps Jesus present in the believer (14:26) and (3) the one who continues Jesus' mission (20:22).

The verb ἁγιάζω29

Disciples (ἁγίασον αὐτούς, 17:17) … Jesus (ἁγιάζω ἐμαυτόόν, 17:19; also 10:36).The first verb reference is found in 10:36. In 10:36, Jesus asks the Jews a rhetorical question (Ridderbos 1997:374; also Newman & Nida 1993:346), namely 'can you say that the one whom the Father has sanctified30 and sent into the world31 is blaspheming because I said, "I am God's Son"?' With these words, Jesus declares that the Father has sanctified him (ὃν ὁ πατὴρ ἡγίασεν) before sending him to the world to do the work the Father has given him to do (see 17:4, 6-8). Here, his consecration is connected with his mission.32

Jesus refers to his consecration again in 17:19. He consecrates himself so that they (his disciples) may also be sanctified in truth (καὶ ὑπὲρ αὐτῶν ἐγὼ ἁγιάζω ἐμαυτόόν, ἵνα ὦσιν καὶ αὐτοὶ ἡγιασμένοι ἐν ἀληθείᾳ). What does this self-sanctification of Jesus entail? According to the Old Testament, humans as well as animals are consecrated (Dt 15:19). Animals are consecrated to be sacrificed and humans to become prophets (see Jr 1:5; Sir 49:7). Priests are consecrated for special tasks (Ex 40:13; Lv 8:30; 2 Chr 5:11). Prophets had to be made holy because they were bearers of the word of God. When Jesus uses the preposition ὑπέρ ('for the sake of/on behalf of', 17:19), he probably has in mind his sacrifice on the cross. The phrase ὑπὲρ αὐτῶν ('on behalf of them') may imply 'his death', as has been suggested by the use of ὑπέρ throughout the Gospel33 (Brown 1972:766).

According to Keener (2003b:1060), God sanctifies his people by making them like himself (17:11; also Lv 11:44-45; 1 Pt 1:16). In 17:11, Jesus addresses the Father as 'holy'. To the Jewish mind, this suggests something about the holiness to be expected from the disciples gathered around Jesus when he is praying this prayer. The principle in Leviticus (11:44; 19:2; 20:26) is that the children of God must make themselves holy because God is holy (cf. also 1 Pt 1:16). The disciples of Jesus actually belong to God (17:9); therefore, they should separate themselves from the world (Brown 1972:765). For John, the holiness of the disciples is to separate them from the values of the world and not the world. Jesus, the Holy One of God (6:69), wants his disciples consecrated and sent into the world (17:18; 20:21; Keener 2003b:1060f.). Their consecration is directed towards their mission. In the Gospel of John, sanctification is always connected to mission. After Jesus' imperative appeal for the sanctification of the disciples (17:17a), the mission of the disciples is spelled out (17:18); it is the continuation of Jesus' mission.34 17:17b focuses on the means of the sanctification: 'Sanctify them by the truth; your word is truth' (Carson 1991:566).

John 17:17b also refers to the medium of sanctification. In this context, the Evangelist points out that 'holiness is not simply a human achievement' (Borchert 2002:203). It is an act of God who consecrates people to be like God. (The disciples are to be sanctified in the truth, that is, the [W]word of God [17:17a].) Therefore, Jesus requests the Father to sanctify his disciples as he has sanctified Jesus and sent him into the world (10:36). In Jewish prayer, it is declared that God sanctifies people through his commandments (Strack & Billerbeck 1969:566). This notion resonates with John's partly similar notion that 'word' and 'commandment' are almost interchangeable. In Johannine theology, Jesus is identified as both 'Word' and 'the Truth' (14:6). This implies that sanctification in truth (the word of God) is basically an aspect of belonging to Jesus. According to 17:10,35 belonging to Jesus is belonging to God, and they are both holy (Brown 1972:766).

Conclusion

Thus far, it is evident that the economic and strategic use of the verb ἁγιάζω and the adjective ἅγιος in the Gospel creates an environment in which the Johannine understanding of the sanctification or holiness of the followers of Jesus is embedded. This implies that holiness belongs to God. He is the owner of himself,36 his being. God's holiness is connected with his presence and mission in the world. As a result, the identity and character of all the three divine persons (FSS) are linked to the existence (das ein) of holiness. Jesus calls imperatively (ἁγίασον, 17:17) on the Father to sanctify his followers. According to John, holiness includes more than only ethical aspects. In fact, holiness is connected with the mission of Jesus and the continuation of this mission by his disciples. The rest of this article focuses on the code of holiness and, finally, the purpose of holiness.37

The code of holiness in the Gospel of John38

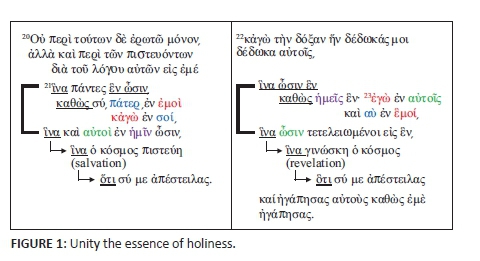

The cryptogram of holiness is explicitly explained in John 17:20-23, where the following extended parallelism39 is found:

This parallelism40 is constituted through the 'grammatical structure, the theological content as well as the rhetorical argument' (Van der Merwe 2002a:227). The parallels are evident in words, phrases and prepositional structures. The Evangelist uses repetition to create effect, to emphasise and to explicate, in this case the unity41 theme, which in John constitutes the matrix for holiness (Van der Merwe 2002a:228).

The first cluster of texts (17:20-21) refers to the exhortation to the disciples to be 'in' (ἐν) Jesus and the Father (ἵνα καὶ αὐτοὶ ἐν ἡμῖν ὦσιν). In the second cluster of texts (17:22-23), Jesus and the Father are said to be 'in' the disciples (23ἐγὼ ἐν αὐτοῖς καὶ σὺ ἐν ἐμοί) (Van der Merwe 2002a:228).42 These formulae of immanence constitute the holiness connection between the disciples and the divine (already depicted as holy). The phrase 'As you, Father, are in me and I am in you, may they also be in us' (17:21). Beasley-Murray (2002:302) interprets this unity as a corporate participation in 'that unity within the Godhead'.

Three interactive levels of relationships are described: the unity between the Father and the Son as the example (καθώς) of holiness (unity), the unity between Jesus and the disciples as the foundation (ἐν) for holiness (unity) and the unity among the disciples as one of the objectives (ἵνα) of holiness. To emphasise this unity among the disciples, Jesus parallels it with the unity between the Father and Jesus. This unity among the disciples is only complete (ἵνα ὦσιν τετελειωμένοι εἰς ἕν) when they are united in God (ἵνα καὶ αὐτοὶ ἐν ἡμῖν ὦσιν) and their unity reflects the holiness of God. Ridderbos (1997:559) points out that the unity intended here by the Evangelist is 'the great object that Jesus aimed for during his life on earth and now desires from the Father for the future as well: "in order that they may be all in one43 even as we are one"'.

In conclusion, the relationship between the Christian community and Jesus (God), according to the Evangelist, mirrors the relationship between the Father and the Son. According to Jesus 'his disciples should be one, just as (καθώς) he and the Father is one' ( ἵνα ὦσιν ἓν καθὼς ἡμεῖς ἕν).44 In other words, certain aspects of the Father-Son relationship (unity) form a template (καθώς, see 17:21, 22) for the character of unity or holiness that the Christian community should display.45 This view, then, values the community as an ongoing locale that was decisive in the historical revelation of God in Christ; it is where holiness is constituted (Kysar 2007:136). Thus, according to the context of John 17, unity and holiness can be interpreted semantically as synonyms.

In order to understand the code of holiness, the unity between the Father and the Son has to be understood. In addition, we must understand what it means that Jesus and the disciples are in one another.

The Father-Son relationship as the example of holiness

According to Poelman (1965:62), the unity between Jesus and the Father is a constant theme in the Gospel of John. The unity between the Father and Jesus is further articulated in the following mutual formula (17:21; cf. also 14:10-11, 20), which forms a chiasm:

σύ, (πάτερ), ἐν ἐμοὶ

κἀγὼ ……. ἐν σοί

Beasley-Murray (2002:253) calls this a 'formula of reciprocal immanence'. Schnackenburg (1968:143) describes it as 'a linguistic way of describing … the complete unity between Jesus and the Father'. Beasly-Murray (2002:254) writes: '[I]n the depths of the being of God there exists koinonia. A "fellowship" between the Father and the Son that is beyond all comparison, a unity whereby the speech and action of the Son are that of the Father in him and the Father's speech and action come to finality in him'.

The first phrase (σύ, πάτερ, ἐν ἐμοὶ) of this chiasm refers to the presence of the Father in the life of Jesus. The second phrase (κἀγὼ ἐν σοί) refers to the desire of Jesus to do the will of the Father. Although Poelman (1965) focuses the attention on the relation between 17:11, 21 and 22f., he neglects to pay attention to Jesus' statements that he speaks the words the Father has given to him to speak and performs the works the Father has shown to him. The unity is further expressed by Jesus who wants to do the Father's will (4:34; 5:30; 6:38; 8:2). This implies that the presence of the Father in the life of Jesus is required to enable Jesus to comply to the will of his Father (Van der Merwe 2002a:229). Consequently, the unity between the Father and the Son implies that it is the Father who performs the work of the Son and who is speaking (cf. Carson 1991:568).46

Therefore, in his historical situation, whoever hears Jesus hears the voice of the Father, whoever sees Jesus sees the Father (14:9) and whoever experiences Jesus experiences the presence of the Father (cf. 12:45, 49, 50; 14:9).47

It can therefore be deduced that the unity between the Father and the Son, as displayed throughout the Gospel, discloses the character of their holiness. This unity between the Father and the Son comprises mutual indwelling, mutual revelation, mutual love and mutual glorification.

The Jesus-Disciple relationship as the foundation for holiness

Beasley-Murray (2002:302) points out that in 14:20 (also 11, 12),20 the statement 'On that day you will know that I am in my Father, and you in me, and I in you' refers to a mutual indwelling of persons. Believers become one through participation in the koinonia of the Father and the Son. In 17:21-23, the disciples' participation is constituted through their union with the Son. This resonates with representations throughout the Gospel of the intermediator role of the incarnate Son of God (e.g. in 17:21-22). In the parallelism of clusters, a second chiasm is present:48

17:21 καθὼς σύ, πάτερ, ἐν ἐμοὶ κα[ὶ] ………. [ ἐ ] γὼ ἐν σοί ,

17:22f [καθώς]49 ἐγὼ ἐν αὐτοῖς , καὶ …….. σὺ ἐν ἐμοί

The first chiasm (17:21), as discussed in the previous subsection, states that the Father and Jesus are in each other. This second chiasm refers to three personae: the Father (σύ), Jesus (ἐγώ, ἐμοί) and the disciples (αὐτοῖς). In both relationships, Jesus is present and part of. In other words, Jesus is the mediator between the Father and the disciples. The statements in the two chiasms make it clear that (1) Jesus and the Father are in each other (17:21) and (2) that he is also in the disciples (17:22f). It can therefore be reasoned that the Father is present in the disciples because he is present in Jesus (cf. Malatesta 1971:207). Functionally, these two chiasms complement each other; they determine and indicate the nature of the 'unity' as well as the 'holiness' implied here. This signifies the nature of the relationship that exists between the disciples and Jesus (even the Father). The implication is that the disciples will take on the character of the Father (e.g. holiness) in Jesus (Van der Merwe 2002a:232).

This explanation shows that the unity claimed by Jesus to be among believers is to be modelled on the 'unique interrelationship of the Father and Son (Word) vividly portrayed in both the pros ton theon ("towards God") and the theos ēn ho logos ("the Word was God") of the Prologue (1:1-3)' (Borchert 2002:206). In the relationship between Jesus and the disciples, the disciples' functioning is contingent upon Jesus, as Jesus' functioning is contingent upon the Father. They only function in relation to the other. Thus, the unity of the disciples with Jesus enables them to perceive the will of God and to live their lives in accordance with his will (Van der Merwe 2002a:232).

The question that arises now is how this 'unity' between Jesus (also the Father) and his disciples, and the unity among the disciples, would be established. Unfortunately, no systematic or even practical modus operandi is given in John 17. We find the answer to this question in the actions that constitute the unity between Jesus and the disciples, which we see throughout the Gospel: their lives must imitate the life of Jesus. This question is addressed in a following publication entitled 'Conceptualising holiness in the Gospel of John: the en route to holiness and the character of holiness according to the Gospel of John'.

Closely connected to the environment and code of holiness is the question: 'What are the objectives for being holy?'

The objectives for being holy in the Gospel of John

The objectives for sanctification in the Gospel of John are to be found in the following four references:

In each text cluster (17:20-21; 22-23), there are three clauses introduced by the subordinating nominal particle ἵνα ('in order that') stating objectives (see Beasley-Murray 2002:303). The first objective ('that they may all be one') refers to the unity to be constituted among the followers of Jesus, which is referred to in 17:20-23 but not defined in this context. The constitution and character of this unity are defined in 15:9-17, namely to abide in Jesus and to love one another (obedience). This is suggested in the phrase at the end of 17:23, 'and loved them even as you loved me' (καὶ ἠγάπησας αὐτοὺς καθὼς ἐμὲ ἠγάπησας). To 'love God and to love Jesus and one another' is the test for holiness in the Gospel of John. 'Love' and obedience of Jesus' commandment will lead to the 'unity' required to continue Jesus' mission:

• 'As the Father has loved me, so I have loved you' (15:9).

• 'This is my commandment, that you love one another as I have loved you' (15:12).

• 'I am giving you these commands so that you may love one another' (15:17).

The second objective ('that they also may be in us') for holiness is closely connected to the first objective: the disciples should be in the divine (αὐτοὶ ἐν ἡμῖν ὦσιν). According to the Evangelist, unity among believers can only be obtained through their unity with Jesus and the Father. The focus is not on the first objective but on the second. Ridderbos (1997:560) agrees that the final goal here is not so much the unity among the disciples as the 'unity in us', 'as we are one'. This unity 'in us'50 substantiates the 'holiness' to which the believers are called. The unity of Christian believers resembles the unity between the Father and Son and reflects its 'ground and character' (Ridderbos 1997:560).

Here, Jesus does have the ontological unity that exists between the Father and the Son51 in mind. He has in mind the unity and the reciprocal immanence between him and the Father as it comes to light in their holiness in the performance of the divine work of salvation. Throughout the Gospel, it is evident that 'the Son can do nothing on his own, but only what he sees the Father doing' (5:19) and 'what he has heard from Him' (cf. 8:26). With these statements, Jesus emphasises 'the complete harmony and concurrence' between him and the Father in carrying out the work of redemption assigned to him by the Father (cf. 2-4,6-13) (Ridderbos 1997:561).

The following two phrases are parallel, connected and stand in a close relationship:

ἵνα καὶ αὐτοὶ ἐν ἡμῖν ὦσιν ('may they also be in us', 17:21)

ἵνα ὦσιν τετελειωμένοι εἰς ἕν ('that they may become completely one', 17:23)

This implies that the participle τετελειωμένοι ('completely', 17:23) is connected to the phrase αὐτοὶ ἐν ἡμῖν ὦσιν ('may they also be in us', 17:21) which means that 'complete unity' among the disciples can only be achieved when they are being taken into the unity of God, to be 'in us' (cf. Köstenberger 2004:498).

The third objective for holiness is 'so that the world may believe/know that you have sent me'. This seems to be the consequence of the petitions for the unity of the followers of Jesus (cf. Beasley-Murray 2002:303)52 mutually and with the divine (Jesus and the Father). Where the first two objectives focus on the disciples of Jesus, the third objective focuses on the world per se.

If holiness is linked to the mission of Jesus (17:18, 19) and the mission of the disciples (17:17, 18), then the purpose of the mission of Jesus will be the purpose of the mission of his disciples. John 1:9 states that the purpose of the mission of Jesus is to give light to everyone. Here, light is a compound word, referring to salvation and revelation in the mission of Jesus and disciples as stated in 17:21, 23.53

ἵ να ὁ κόόσμος πιστεύῃ ὅτι σύ με ἀπέστειλας (salvation)

ἵ να γινώσκῃ ὁ κόόσμος ὅτι σύ με ἀπέστειλας (revelation)

The function of the chiasm (ὁ κόόσμος πιστεύῃ, γινώσκῃ ὁ κόόσμος) in this parallelism is to emphasise this objective.

The fourth objective is indirectly connected to the glory motif in John 17. This objective of the consecration of believers focuses on the glorification of the divine. It relates to the mission of Jesus, who reports to the Father as follows: 'I have glorified you on earth by finishing the work you gave me to do' (17:4). The subjective component in John regarding holiness is subordinate to the objective component. The focus is not on the self but rather on the Other (the divine) - the glorification of God when the world (ὁ κόόσμος) believes (πιστεύῃ) and knows (γινώσκῃ) that God has sent his Son (ὅτι σύ με ἀπέστειλας).54 Although the notion 'glory' has a variety of meanings,55 in John 17 (cf. Van der Merwe 2002b:226-249), I only focus on two of these meanings that are relevant to this research (17:4; 24).56 Firstly, If Jesus glorifies the Father by completing the mission the Father has given him (17:4), then those who continue with this mission glorify the Father first because they are holy and connected to Jesus (15:8). Secondly, those who live in unity with the divine (17:22) will see the glory of Jesus because they will be with him (17:24).

Conclusion

John regards holiness as (1) a matter of identity (to be identified and united with a specific God), (2) a matter of character (to imitate the life of a specific person, the Son of this God) and (3) an empirical matter of revelation, salvation and glorification (in which the holiness of Christian believers has a revelatory-salvific effect, through the critical involvement of the Holy Spirit).

Because the community is the locus of the manifestation of God (Kysar 2007:135) in this world, John regards holiness as the revelation of God in this world - to make this being visible, so that when people hear the Christian believer they should hear God speaking; when they see the conduct of the Christian believer they will see God acting in this world; when people experience the presence of the Christian believer they should experience the transcendence and the imminence of this God.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationships which may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

References

II Maccabees, quoted from The New Catholic version of the Bible in English (The New American Bible). [ Links ]

III Maccabees, viewed 16 February 2015, from http://ecmarsh.com/lxx/III%20Maccabees/index.htm [ Links ]

Appold, M., 1978, 'Christ alive! Church alive! Reflections on the prayer of Jesus in John 17', Currents in Theology and Mission 5, 365-373. [ Links ]

Arndt, W., Danker, F.W. & Bauer, W., 2000, A Greek-English lexicon of the New Testament and other early Christian literature, 3rd edn., University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL, p. 36. [ Links ]

Barrick, W.D., 2010, 'Sanctification: The work of the Holy Spirit and Scripture', The Masters Seminary Journal 21(2) (Fall of 2010), 179-191. [ Links ]

Beasley-Murray, G.R., 2002, John, Word Biblical Commentary vol. 36, Word, Incorporated, Dallas. [ Links ]

Borchert, G.L., 2002, John 12-21, Broadman & Holman Publishers, Nashville, TN. [ Links ]

Brown, C., 1976, The Dictionary of New Testament Theology, vol. II, Paternoster Press, Exeter. [ Links ]

Brown, F., Driver, S.R. & Briggs, C.A., 2000, Enhanced Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon (electronic ed.), Logos Research Systems, Oak Harbor. [ Links ]

Brown, R.E., 1972, The Gospel according to John (Vol. II, The Anchor Bible), Geoffrey Chapman Publishers, London. [ Links ]

Brown, R.E., 1975, The Gospel according to John (Vol. 1, The Anchor Bible), Geoffrey Chapman Publishers, London. [ Links ]

Brown, T.G., 2003, Spirit in the writings of John: Johannine pneumatology in social-scientific perspective, T & T Clark International, London. [ Links ]

Carson, D.A., 1991, The Gospel according to John, Inter-Varsity Press, Leicester. [ Links ]

De Vaux, R., 1973, Ancient Israel: Its life and institutions, Darton, Longman & Todd, London. [ Links ]

Didache, viewed 16 February 2015, from http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/didacheroberts.html [ Links ]

Dunn, J.D.G., 1975, Jesus and the Spirit: A study of the religious and charismatic Experience of Jesus and the first Christians as reflected in the New Testament, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Friberg, T., Friberg, B. & Miller, N.F., 2000, Analytical lexicon of the Greek New Testament. Baker's Greek New Testament Library, vol. 4, Baker Books, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Grayston, K., 1981, 'The meaning of PARAKLETOS', Journal for the Study of the New Testament 13, 67-82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0142064X8100401305 [ Links ]

Harrington, H.K 2004, The purity texts, T&T Clark, Edinburgh, viewed 19 February 2016, from https://books.google.co.za/books?id=diN3AlhZ6PkC&pg=PA1976&lpg=PA1976&dq =1QS+9.6&source=bl&ots=ZMw1ja5uIR&sig=4eHEMmej1nME1hUDHoqLU23zCl4&hl= en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjFzraKt4TLAhWE2hoKHdMQB0YQ6AEIHTAB#v=onepage&q= 1QS%209.6&f=false [ Links ]

Joubert, H.L.N., 1968, '"The Holy One of God" (John 6:69)', Neotestamentica 2, 57-69. [ Links ]

Käsemann, E., 1968, The testament of Jesus: The Gospel of John in the light of Chapter 17, transl. G. Krodel, SCM, London. [ Links ]

Keener, C.S., 2003a, The Gospel of John: A commentary, vol. I, Hendricksen Publishers, Peabody. [ Links ]

Keener, C.S., 2003b, The Gospel of John: A commentary, vol. II, Hendricksen Publishers, Peabody. [ Links ]

Koester, C.R., 2008, The word of life. A theology of John's Gospel, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Köstenberger, A.J., 1998, The missions of Jesus and the disciples according to the Fourth Gospel, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Köstenberger, A.J., 2004, John, Baker Academic, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Kysar, R., 2007, John: The maverick Gospel, Westminster John Knox Press, London. [ Links ]

Louw, J.P. & Nida, E.A., 1996, Greek-English lexicon of the New Testament: Based on semantic domains, United Bible Societies, New York. [ Links ]

Malatesta, E., 1971, 'The literary structure of John 17', Biblica 52, 190-214. [ Links ]

Malina, B.J. & Rohrbaugh, R.L. 1998, Social-science commentary on the Gospel of John, Fortress Press, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Newman, B.M. & Nida, E.A., 1993, A handbook on the Gospel of John, UBS Handbook Series, United Bible Societies, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Neyrey, J.H., 2007, The Gospel of John, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Poelman, R., 1965, 'The Sacerdotal Prayer: John XVII', Lumen Vitae 20, 43-66. [ Links ]

Randall, J.F., 1965, 'The theme of unity in John XVII 20-23', Ephemerides Theologicae Lovanienses 41, 373-394. [ Links ]

Ridderbos, H., 1997, The Gospel of John. A theological commentary, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Schnackenburg, R., 1968, The Gospel according to St John, Burns and Oates, London. [ Links ]

Sheldrake, P., 1995, Spirituality and history, SPCK, London. [ Links ]

Strack, H.L. & Billerbeck, P., 1969, Das Evangelium nach Markus, Lukas und Johannes und die Apostelgeschichte erlautert aus Talmud und Midrasch, [ Links ] [n.i.], [n.i.]. C.H. Beck'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, München.

Van der Merwe, D.G., 2002a, 'The character of unity expected among the disciples of Jesus according to John 17:20-23', Acta Patristica et Byzantina 13, 222-252. [ Links ]

Van der Merwe, D.G., 2002b, 'The glory-motif in John 17:1-5: An exercise in Biblical semantics', Verbum et Ecclesia 23(1), 226-249. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ve.v23i1.1250 [ Links ]

Van der Merwe, D.G., 2014, Eenheid as matriks van die spiritualiteit van die Evangelie volgens Johannes, LitNet Akademies 11, 372-400. [ Links ]

Waaijman, K., 2002, Spirituality: Forms, foundations, methods, Peeters, Leuven. [ Links ]

Westcott, B.F. & Westcott, A. (eds.), 1908, The Gospel according to St. John Introduction and notes on the Authorized version, Classic Commentaries on the Greek New Testament, J. Murray, London. [ Links ]

Zimmerli, W., 1978, Old Testament Theology in outline, transl. D.E. Green, T&T Clark, Edinburgh. [ Links ]

Zodhiates, S., 2000. The complete word study dictionary: New Testament, AMG Publishers, Chattanooga, TN. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Dirk van der Merwe

dirkvdm7@gmail.com

Received: 04 Apr. 2016

Accepted: 09 Aug. 2016

Published: 24 Feb. 2017

1 This article was a paper read at the annual international conference of the Society for the Study of Christian Spirituality (SSCS) during 20-23 May 2015 at St Augustine College of South Africa, Johannesburg. The conference was very well attended, which verifies the above statement about the interest in Christian Spirituality. Well-known international scholars like Waaijman, McGinn and Weltzen were there as well as well-known South African scholars in Christian Spirituality, such as De Villiers, Kourie and Lombaard. The extensive work of Schneiders on the Gospel of John, the publication of Waaijman (2002) as well as the publication of Sheldrake (1995) influenced me in doing this research on 'Holiness in the Gospel of John'. Spirituality can, for the purpose of this research, be defined to refer to 'living a life of transformation and self-transcendence that resonates with the lived experience of the divine' (Van der Merwe 2014:374). Although two dimensions are distinguished in this definition, they are continuously interactive. Christian spirituality then reflects on the experience of God in the life of the believer with the emphasis on the experience of God.

2 Cf. Barrick (2010:180), who refers to only two.

3 Friberg, Friberg and Miller (2000:203) interpret it as '(1) with a basic meaning what belongs to divinity, sacred, holy (2T 3.15), opposite βέβηλος (profane); (2) substantivally; (a) τὸ ἱερόν as a sacred enclosed area under the protection of a god temple (AC 19.27); (b) predominately of the temple of God at Jerusalem, including the whole sacred area with its buildings, courts, walls, and gates (MT 21.12); (c) τὰ ἱερά as everything that belongs to the temple and its service the holy or sacred things (1C 9.13)'.

4 Zodhiates (2000:#3741) distinguishes ὅσιος from δίκαιος (righteous) which, according to him, refers to human laws and duties.

5 Cf. the work of Barrick (2010:180f). For Arndt et al. (2000:728), it means '[pertinent] to being without fault relative to deity, devout, pious, pleasing to God, holy'. For Friberg et al. (2000:286), it refers to 'what is sanctioned by the supreme law of God; (1) of persons who live right before God holy, devout, dedicated (TI 1.8); (2) of the inherent nature of God and Christ holy (HE 7.26); substantively ὁ ὅ. the Holy One (AC 2.27); (3) of things holy, divine; neuter as a substantive τὰ ὅσια holy decrees, divine promises (AC 13.34)'.

6 This essay was presented as a paper at the Bi-annual Meeting of the Society for the Study of Christian Spirituality (SSCS), Johannesburg (South Africa), 2015.

7 This mission comprises the revelation of the Father (1:18) and the Son (references to see and hear); the salvation of mankind (3:16); and the glorification of Father (17:1, 4), Son (17:1, 5, 24) and disciples (17:22; cf. 12:43). To this we can also add the judgment of the Son, 'The Father judges no one, but has given all judgment to the Son, that all may honor the Son, just as they honor the Father' (5:22-23).

8 This reference to God by Jesus in 17:11 is a form of address: see 17:1, 5, 24 (Carson 1991:561; Köstenberger 2004:493; Beasley-Murray 2002:298).

9 See the use of 'holy Lord' (1 En., 91:7) and 'holy God' (Sib., 3.478) in early Jewish documents. Even in early Christian circles, 'holy Father' became more popular (Did 10.2; Odes. Sol, 31:5) (cf. Keener 2003b:1057). According to Westcott (1908:243), Holy Father is a distinctive form of address (comp. Rv 6:10; 1 Jn 2:20; v. 25, righteous Father). It suggests the main thought in this context.

10 Quoted from The New Catholic version of the Bible in English (The New American Bible).

11 Available at: http://ecmarsh.com/lxx/III%20Maccabees/index.htm. Retrieved: 16/02/2015.

12 Available at: http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/didache-roberts.html. Retrieved: 16/02/2015.

13 See Barrick (2010:181-182) for a biblical demonstration of the holiness of God.

14 Barrick (2010:180f.) distinguishes two sides of holiness. Holiness 'refers to that which is totally other, that which one dedicates completely to God alone'. According to the Scriptures, it is an attribute fundamental to the character of God.

15 Malina and Rohrbaugh (1998:247) point out that in the New Testament there exists a custom that reference to a specific person was to refer to that person's 'name'. Thus, in John 17:6, the making known of the name of the Father was to manifest the Father himself.

16 See, for example, Exodus 28:36; 30:10, 32, 36-37; 31:145; 29:30; Leviticus 21:6-8.

17 Keener (2003a:697) mentions that this reference to God as 'the Holy One' was in particular used as a title for God himself in the Old Testament and in early Judaism.

18 This expression relates closely to 10:36 and 3:31-34.

19 In his commentary on this passage, Brown (1975:298) refers to the Old Testament occurrences where references such as 'God's holy one' or 'the Lord's holy one' refers to men consecrated to God (Jdg 13:7; 16:17, Samson; Ps 106:16, Aaron).

20 Joubert (1968:57-69) argues that the title has a more exalted meaning: King, Son of Man, Suffering, servant and Son of God (cf. also Neyrey 2007:134).

21 This may also refer to the Logos who was with God (1:1-5) and Jesus' statement in 17:20-23 that he and the Father are in each other.

22 In John 14:23, the noun 'staying' (ἐντολή) is used for 'indwelling and continuous habitation' (Keener 2003a:460).

23 The verb form μένων (14:25) is a present active participle and μένει (14:17) a present active indicative that means 'continuous habitation'.

24 Prior to its use by the Evangelist, Paraclete has meant 'mediator' or 'broker' (Brown 2003:170-186) or has been translated as 'patron' or 'supporter' (Grayston 1981:67-82). See Keener (2003b:951-972) for a thorough discussion of the Paraclete.

25 A 'tandem' relationship exists between the ministries of Jesus and the Paraclete. 'Both come forth from the Father (15:26; 16:27f.); both are given and sent by the Father (3:16f.; 14:16, 26); both teach the disciples (6:59; 7:14, 28; 8:20; 14:26); both are unrecognised by the world (14:17; 16:3). It is implied in 19:30 (probably) and 20:22, where the Spirit is depicted as the spirit/breath of Jesus. Above all, it is indicated in the explicit description of the Spirit as the other Paraclete or Counsellor, where Jesus is clearly understood as the first Paraclete (I John 2:1); and by the fact that the coming of the Spirit obviously fulfils the promise of Jesus to come again and dwell in his disciples (14:15-26). In short, the Paraclete is the presence of Jesus when Jesus is absent. The Spirit has taken on a fuller or more precise character - the character of Jesus: the personality of Jesus has become the personality of the Spirit. As the Logos of revelation (and Wisdom) has been identified with the earthly Jesus and stamped with the impress of his character (1:1-18), so the Spirit of revelation has been brought into conjunction with the heavenly Jesus and bears the stamp of his personality' (Dunn 1975:350-351).

26 The same is true of Jesus. He says, 'What I speak, therefore, I speak just as the Father has told me' (12:50).

27 Keener (2003b:1204-1205) points out that breathe (ἐνεφύσησεν) is a rare verb that occurs only in Genesis 2:7 (ἐνεφύσησεν, LXX) and Ezekiel 37:9 (ἐμφύσησον, LXX).

28 Keener (2003b:1205) connects this reference to the 'Holy Spirit' (20:22) with the other two references to the 'Holy Spirit': the Spirit of purification in 1:33 and the Spirit of prophecy in 14:26.

29 This verb is used only four times in the Gospel: 10:36; 17:17, 19 (bis).

30 According to the Jewish tradition, God had sanctified Israel. He set them apart for himself (Jub 22:9; 30:8; Wis 18:9; 3 Macc 6:3; 1 Cor 1:2; 1 Clem 1:1.). Priests (and Levites) were consecrated (שַׁדָק) to God in some special way. They were not given any land in Canaan (Dt 18:1-5) so that they could devote themselves to the work of God (especially in and around the Temple) (Keener 2003b:1060). See also De Vaux (1973:460-467) for a discussion on purity. Harrington (2004:3.1) who has studied the purity concept in Qumran in depth, points out that the holiness and impurity concepts are intensified by the Qumran authors. They identify classifications (categories) of holiness which they interpret maximally. According to her the Qumran community regards the whole community as holy, and not only the priests. The Qumran writers call the community the 'holy house of Aaron' (1QS 9.6); 'holy among all the peoples' (1Q 34 3 ii 6), 'assembly of holiness or holy community' (1QS 5.20; 9.2; 1Q 28a 1.9, 13; 'holy Counsel' (1QH 15.10; 1QM 3.4; 'the holy ones' 1Q33 6.6; 'God's holy temple' (1Q33 14.12; 'men of holiness' (1QS 8.17); and so on.

31 I cannot agree with Ridderbos (1997:374), who interprets this reference to mission as the mission of the disciples.

32 Köstenberger (1998:189-190, 2004:497) states that both love (13:34-35; 15:12-13; 17:26) and unity are vital requirements for the missions of the disciples.

33 '[T]hat Jesus was about to die for (ὑπὲρ) the nation' (11:51); 'The good shepherd lays down his life for (ὑπὲρ) the sheep' (10:11); 'No one has greater love than this, to lay down one's life for (ὑπὲρ) one's friends' (15:13).

34 According to Sirach 45:4 (in KJV), 'God selected him [Moses] from all mankind'. Now, in Exodus 28:41, God tells Moses to consecrate others so that they may serve God as priests. Similarly, the disciples of Jesus are to be consecrated in order that they may serve as apostles (Brown 1972:765).

35 'All mine are yours, and yours are mine …'

36 The expression 'I am who I am' indicates that he belongs totally to himself.

37 The en route to holiness will be dealt with in a follow-up article.

38 In this subsection I rely on a previous publication of mine, Van der Merwe (2002a).

39 Ridderbos (1997:559) states that verses 21-23 consist of 'two strophes'. See also Borchert (2002:205), Beasley-Murray (2002:303) and Randall (1965:141), who identify a parallelism in 17:20-23.

40 The function of this parallelism is, firstly, to emphasise the unity aspect and, secondly, to relate the purpose of the mission of Jesus (salvation and revelation) with this concept of unity. This refers implicitly to 17:1-5, where the glory of God and Jesus is explained and emphasised.

41 The unity among Jesus' disciples has already been introduced to prepare the reader in 17:11.

42 The modifications in the second cluster provide new perspectives. This is clear from the introduction of new themes: δόξαν, ἠγάπησας, τετελειωμένοι (Van der Merwe 2002a:228).

43 The clause 'in order that they may all be one' appears in 17:11, 21, 22 and 23.

11: ἵ να ὦσιν ἓν καθὼς ἡμεῖς 21: ἵ να καὶ αὐτοὶ ἐν ἡμῖν ὦσιν 22: ἵ να ὦσιν ἓν καθὼς ἡμεῖς ἕν 23: ἵ να ὦσιν τετελειωμένοι εἰς ἕν\

44 The unity among the disciples and Jesus (God) is not an 'ontological' unity but a 'functional' unity. This unity lies in: obedience (say and do, will of God), love, glorification, abiding in and laying down one's life (die in oneself).

45 For example: 'As (καθώς) the Father has loved me, so I have loved you (15:9) … This is my commandment, that you love one another as (καθώς) I have loved you' (15:12). Thus, as the Father loves the Son, so the believers are to love one another. 'If you keep my commandments, you will abide in my love, just as (καθώς) I have kept my Father's commandments and abide in his love' (15:10).

46 Borchert (2002:206) describes the oneness of believers in the community as 'modelled on the interrelationship of the Father and the Son (you are in me and I am in you'. Also see Appold (1978:157-93).

47 He speaks (3:34; 8:28; 12:49, 50; 14:10) what the Father has told him to say; he does (4:34; 5:36; 14:10; 17:4; cf. 10:25, 37) what the Father has shown him. He does the will of God (4:34; 5:30; 6:38; 8:29).

48 Compare this chiasm (17:21-22) with the chiasm in 14:20. (Also consider 14:10f.)

20 ἐν ἐκείνῃ τῇ ἡμέρᾳ γνώσεσθε ὑμεῖς ὅτι …ἐγὼ……. ἐν τῷ πατρί μου καὶ ὑμεῖς ἐν ἐμοὶ κἀγὼ ….. ἐν ὑμῖν.

49 The comparative particle καθὼς is implied at the beginning of 17:22.

50 Borchert (2002:206) points out that the idea of 'indwelling' of believers in the Godhead can be understood from the indwelling of the vine and branches described in John 15:1-11.

51 This is the opposite of the understanding of Käsemann (1968:56ff) who refers to a participation of believers in the ontological unity of the Father and the Son (see also Ridderbos 1997:560).

52 Cf. Beasley-Murray (2002:303) for a discussion on whether this third ἵνα- clause should be regarded as a consequence of the first two ἵνα- clauses or not.

53 In 1:14, 18 it is written that Jesus will reveal (make known) the Father and glorify the Father (17:4). In 9:39, judgment is given as purpose for the coming of Jesus (also 15:22); in 10:9-10, he came to give salvation and abundant life. In 12:47, it is written that the purpose of his coming is salvation and not judgment and in 18:37, it is the witness of Jesus to the truth. All these relate to salvation.

54 The verb 'believe' refers to the salvation which Jesus brought and the verb 'know' refers to his revelation of the Father. The subjunctive mode of both of these words verifies this statement. The two verbs know (γινώσκω) and believe (πιστεύω) are collective verbs. The verb 'believe' (πιστεύω) refers to the entire process of salvation described in the Gospel, and the verb 'know' (γινώσκω) refers to the entire process of revelation as described in the Gospel.

55 See my publication, Van der Merwe (2002b).

56 17:4, 'I glorified you on earth by finishing the work that you gave me to do'; 17:24, 'Father, I desire that those also, whom you have given me, may be with me where I am, to see my glory'.