Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

HTS Theological Studies

versión On-line ISSN 2072-8050

versión impresa ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.72 no.3 Pretoria 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v72i3.3338

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Truth and falsehood in Judith: A Greimassian contribution

Risimati Synod Hobyane

School of Ancient Language and Text Studies, Faculty of Theology, Northwest University, Potchefstroom Campus, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Narratives are never meant to be neutral in their rhetorical intent. They have power not only to reveal realities and prevail worldviews but also to create new realities and new worldviews by refuting illusions and falsehood, and affirming the truth. The Judith narrative is a good example for the exploration of this claim. This article contributes by employing the thematic level of analysis, the veridictory square in particular, of the Greimassian approach to narratives, to map out the possible illusions and affirming the truth within the second temple Judaism. The study of the veridictory square as informed by the level of analysis, mentioned above, seems to persuade the reader by first, extracting the truth from illusion and thereafter exposing and shaming falsehood in Judith. Subsequently, the article asserts that Judith is not neutral in its intent but was designed to deal with illusive ideas that might have been impacting the well-being of the second temple Judaism.

Introduction

The book of Judith is one of the most beautiful as well as controversial books in apocryphal literature (Roitman 1992:31). With regard to the date of authorship, Esler (2002:107) asserts that there are a number of features of the text which indicate a provenance in the Maccabean/ Hasmonean period, around 167-63 BCE. Judith is a story of 16 chapters, divided into two parts, traditionally called Part I (1-7) and Part II (8-16) (Harrington 1999:27; Nickelsburg 2005:97). The two parts complement each other: Part I introduces a crisis-facing Israel and Part II brings the resolution to the crisis (Hobyane 2014:910, see also White 1992:6). One of the most intriguing parts of Judith is how the author and/or editor portrays characters in both parts of the story, for example, in Part I, Nebuchadnezzar, Holofernes and the Assyrian army are portrayed as strong and brutal while everything about the Western nations, including Israel, is weak and under utter destruction. Part I is a narration of Holofernes (helped by his Lieutenant, Bagoas) carrying out Nebuchadnezzar's orders to destroy the Western people and their holy places, so that Nebuchadnezzar alone will be worshipped as God (Esler 2002:114). Part II, however, presents a sad ending with reference to Nebuchadnezzar, Holofernes and the rest of the Assyrian army, as Judith and the Israelite armies destroy them (see also Harrington 1999:27). The narrative ends with joy and jubilation on the side of the Jews1 and/or Israel while the Assyrian army look weak, stupid and helpless. This style of ending the story is not neutral in its intent. It challenges the reader/researcher to ask some questions; to mention few:

• Firstly, what could be the author's and/or editor's possible objective of choosing to end the story in this manner?

• Can some valuable deductions be made from how characters are portrayed in both parts of the story? For example, Assyrians appear to be brilliant in Part I but actually stupid in Part II. Equally, Israelites seem to be weak in Part I but brilliant in Part II.

• Why do some characters know more than others in the story? For example, Achior knows the history of the Israelites better than any other character within the Assyrian camp. Likewise, Judith is wiser and more knowledgeable on her view of God than the elders (see Nickelsburg 2005:98).

• Is there any significant deduction that can be made from the author's and/or editor's possible intention of exposing and shaming falsehood or illusion and reaffirming truth about Judaism through the story?

This article acknowledges that some of these questions have been dealt with by other scholars employing various approaches of analysis but not from the Greimassian perspective, particularly the veridictory square. Therefore, it is hypothesised here that the use of the veridictory square as employed by the Greimassian approach brings yet another perspective of reading Judith. It seems that the role played by the Assyrian army in the Judith narrative is nothing else than a false threatening symbol used artificially to unite the house of Israel, and thereby reaffirming the objective truth the editor and/or author desired to bring across through the story. Rhetorically speaking, the Assyrian army (Holofernes) is thus a falsehood employed to eventually reveal the truth regarding Second Temple Judaism.

Synopsis of the approach of analysis

The investigation of truth and illusion in Judith will be done by employing a Greimassian semiotic approach to narrative texts, which according to Taylor and Van Every (1999:52) has proven to be most fully elaborated and subtle of any we have encountered.

For the purpose of clarity, the terminology and concepts of the Greimassian approach to narrative texts are briefly discussed below. The approach consists of three levels of analysis, namely: figurative, narrative and thematic analysis (Hobyane 2015a:639-640). The investigation in this article focuses on the third level of analysis, namely: the thematic level. The three levels of analysis can be briefly defined as follows:

• According to Everaert-Desmedt (2007:30), the figurative analysis focuses on the construction of figures or characters in the story. It is in this level where characters are created and assigned their role in the story (see also Hobyane 2015b:373).

• The investigation in the narrative level focuses on the organisation of a text as discourse. It helps to reveal different functions of actants and track the course of the subject across the narrative (Hobyane 2012).

• Finally, the thematic level 'is the abstract or conceptual syntax where the fundamental values which generate a text are articulated' (Martin & Ringham 2000:12; see also Kanonge 2009:57). Kanonge (2009:57) points out that these values are thereafter investigated syntagmatically by means of the thematic itinerary and presented on a semiotic square, which is the main tool for investigation at this level.

The focus here is on the one aspect of the thematic level of analysis which contributes to addressing the issue of truth and illusion in Judith, namely, the semiotic square of veridiction.

Semiotic square of veridiction

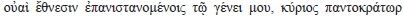

It must be noted that the overall focus of the thematic analysis is broader than what this article aims to achieve. Therefore, as indicated above, only the semiotic square of veridiction (also known as a veridictory square) will be of significant importance here. According to Martin and Ringham (2000:12), the semiotic square of veridiction is a visual presentation of the elementary structure of meaning. It articulates the relationships of opposition, contradiction and implication in the story.

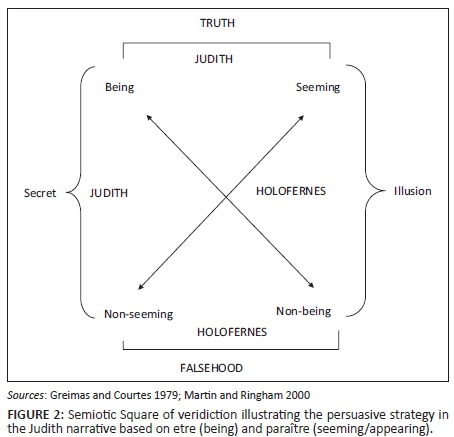

In some narratives, it is difficult to judge actions of competing subjects; the Judith narrative is a good example in this regard, as will be seen in the analysis of the story. Actions of one subject may appear to be true or real while that is not the actual case. There is a conflict between being and seeming. In these types of narratives, there is a manipulation of truth to convince (Hobyane 2012:19). A veridictory square is introduced to map out the truth. Être (being) and paraître (seeming) constitute the two basic modalities of the veridictory square (Greimas & Courtes 1982:194). Figure 1 shows the following configurations (cf. Courtes 1991:11-119, 1995:81-84; Martin & Ringham 2000:139).

In summary, the thematic step comprises three tools of investigation, viz. opposition of values, the thematic itinerary and the veridictory square. A detailed explanation of the concepts and terminology will be dealt with in the analysis of the story.

The analysis of Judith: Application of the veridictory square

According to Martin and Ringham (2000:139), the term 'veridiction' designates the process of truth-telling in a story. Hobyane (2012:142) states that it is connected to the circulation of knowledge, or lack of it, within the text, for example, some actors know more than others about what is happening in the narrative; some are being deceived, others misunderstand and so on. Kanonge (2009:172) argues that the main concern of storytellers is persuasion about truth and falsehood and this is what veridiction is all about.2 The production of truth corresponds to exercising a particular cognitive doing or a causing to appear as true (Kanonge 2009:172). He further argues that the concern of such manipulation of truth is 'causing to believe' and this technique of persuasion characterises many biblicle stories.3

Judith contains, in its many scenes, veridictory modalities: être and paraître (being and seeming/appearing). As already alluded to, veridiction is also important in the analysis of Judith. It enables the reader to discover the truth that the author and/or editor desires to convey and the falsehood that he wishes to oppose or expose. The roles played by few main characters in the story can be set apart as good examples for this. It is observed here that characters like Nebuchadnezzar (along with Holofernes and his army), Judith and God form the most influential mode of persuasion in answering the question 'who is the true god in the narrative?' or 'who actually must be worshipped?' The veridictory modalities, être and paraître, can be mapped out from the role played by these influential characters in the story.

The story of Judith begins with successful campaigns by Nebuchadnezzar (advocated by Holofernes and his army) (1:1-2:13). Furthermore, in 2:21-3:10 the text reports that Holofernes and his army sweep across Mesopotamia and down into Syria and Palestine (Nickelsburg 2005:98). This part of the narrative is certainly dominated by statements and phrases which elevate Nebuchadnezzar's power and arrogance as irresistible and unstoppable. A few examples can be cited from the text. Firstly, in 1:5 the reader learns of Nebuchadnezzar making war (καὶἐποίησενπόλεμον4-and he made war) against king Arphaxad, and later in the chapter, in verse 1:13, the story reports that Nebuchadnezzar prevailed (έκραταιώθη) and he overthrew all the power of Arphaxad.

The text reports that Nebuchadnezzar achieves victory against Arphaxad regardless of the strong security infrastructure which Arphaxad had built around his city, as reported in 1:1-4. Secondly, in 2:5 Nebuchadnezzar continues to make claims that promote him to be some kind of deity to be worshipped by all the nations. Hobyane (2012:143) points out that Holofernes is determined to destroy all the gods of the land, so that all tongues and tribes should worship and/ or serve (λατρεύσωσι) Nebuchadnezzar as the only god (see also Kaiser 2004:40). Nebuchadnezzar calls himself 'the great king, the lord of the whole earth' (όβασιλεύςόμέγας, όκύριοςπάσηςτηςγñς). He sees himself above everyone. Furthermore, those who utter ideas which are contrary to his wishes are banished (e.g. Achior in Chapter 5). The reader wonders if he will banish and destroy all the nations (including Judith). He makes the children of Israel starve to death (7:19-22) and comes close to forcing them to surrender their city and the temple. Again here, the reader wonders if the children of Israel will suffer forever and surrender the city and the temple to him.

Harrington (1999:28) observes that central to the plot of Judith is the theological question: Who is the Lord? Is it Nebuchadnezzar, as Holofernes also proclaims? Or is it the God of Israel, as Judith eventually proves? The question is: 'whose claim is true and which one is falsehood?'; 'Is Nebuchadnezzar really the lord of the whole earth?'

In summarising Nebuchadnezzar's role and all his successes in the story, it can be argued, on the one hand, that he appears (paraître), from the beginning of story, to be in total control over everyone and everything. His claim, complemented by all his battle successes could make the reader wonder, 'Who can and/or will stop this king?' The manner in which he destroys all the nations and their sacred spaces makes him seem unstoppable and unchallengeable.

On the other hand, Nebuchadnezzar's dominance and religious claim in the first seven chapters of the story cause the Jewish religion to appear (paraître) weak and defenceless.

However, the introduction of Judith in Chapter 8 serves as a turning point in the narrative and steers the story to a different direction, as Nickelsburg (2005:98) also observes. As alluded to above, some characters are made (by the narrator and/or editor) to know more than others in the story; Judith's knowledge/view of God proves to be better than that of the elders, just as it was the case with Achior within the Assyrian camp. Roitman (1992:31) observes that Achior knows the sacred history of Israel exceedingly well despite being a pagan. Levine (1992:17) indicates that Judith, in this regard, is identified as a true representation of the Jewish community of faith. Contrary to Holofernes and his army, the story presents Judith as a God-fearing or religious woman (θεοσεβής in 11:17), wise (ήσοφίασου in 8:29) and brave woman (see Moore 1992:61 on Judith's bravery). In her quest to save her people she declares to the Elders in 8:32 that she will do 'a thing which shall go throughout all generations to the children of our nation'.

Judith is introduced to advocate the truth regarding Judaism and proves that the 'true Lord of the whole earth' is the God of Israel. Judith's declaration certainly challenges the claim of Nebuchadnezzar and his army general. Judith is the agent of the veridictory modality être (being) with regard to God and the Jewish religion in the story, as Harrington (1999:28) also acknowledges.

In brief, the persuasive strategy of communication in the Judith narrative shifts from 'Assyrian religious claims' or 'falsehood' (Nebuchadnezzar claims to be a true god) to truth (the God of the Jewish religion is the true God). Consequently, the God of Israel's intervention, through the character of Judith, preserves the Jewish religious values. On the other hand, Nebuchadnezzar starts his journey in the story as the one appearing (paraître) to be in total control. However, Judith's role exposes the lies/falsehood of Nebuchadnezzar and his people. By so doing she also exposes the truth concerning the true Lord of the whole earth, that is, the God of the Jewish religion.

Based on these two modalities, être and paraître (being and appearing), the semiotic square illustrating the persuasive strategy in the Judith narrative can appear as follows: (cf. Greimas & Courtes 1979:359; Martin & Ringham 2000:139).

The semiotic square in Figure 2 illustrates the persuasive strategy of the author in the Judith narrative. Kanonge (2009:175) states that this technique of communication does not aim at producing 'objectively true' discourses, but efficiently persuasive discourses. He further states that the construction of persuasive truth may even comprise illusion. This illusion serves to produce some effects of truth and persuades people to act.

Based on the two veridictory modalities discussed above, être and paraître (being and appearing), the story of Judith can be divided into two parts, that is, its traditional two parts (Part I and II).

In the first part of the story (Chapters 1-7), the construction of the persuasive truth concerning the Jewish religion and the Assyrian cult is based on appearance. In the first place, the Assyrian cult appears to be powerful and unstoppable. Nebuchadnezzar appears indeed to be the lord of the whole earth, but this is not the case. It is only an illusion that Holofernes will destroy all the nations and subdue them.

In the second place, the Jewish religion appears to be weak and defenceless. Before the entry of Judith, 'the elders (men) are weak, stupid and impaired' as Levine (1992:20) puts it, and are not able to stand against the enemy. They lack necessary and sufficient knowledge and skills to deal with the situation. However, this situation changes when Judith enters the story.

Therefore, the Assyrian cult and the Jewish religion are judged according to their performance in the process of attacking their enemies and defending themselves, respectively. Only the narrator/editor of the story and the Lord God of Israel, at this stage, know the objective truth about Judaism and Assyrian cult. The knowledge concerning the strength of the Jewish religion and weakness of the Assyrian cult is kept a secret by the author until victory (by Judith) and defeat (of Holofernes) is realised in 13:8-16:25.

The empty conviction of the Assyrians concerning Nebuchadnezzar as 'the king of the whole earth' is merely based on the performance of his army which appears (paraître) to be unstoppable. This leads them to think (illusion) that the Assyrian cult will become an eligible alternative religion for the Jews or the whole world. In 3:2-7 the text reports that this appearance persuades many to submit to Nebuchadnezzar's power. In 7:23-32 the Elders of Bethulia are also on the verge of surrendering the city to Holofernes. In other words the Jewish religion and its God is displayed as (appears to be) weak and defenceless. Consequently, in 7:24 the children of Israel begin to see the Assyrian cult as something to make peace with, when they say to Ozias:

. [Let God be judge between us and you, for you have done unto us a great injustice because you did not seek peace with children of Assyria]

The reader already knows that the Assyrian cult is wicked and immoral but in the above quotation they are made to appear as if they are peaceful and reliable.

In the second part of the story (Chapters 8-16), truth is based on être (being) and is advocated by Judith and Holofernes. Judith goes all out to prove that the God of Israel is the true God. She does this by first playing an ironic game with Holofernes. Craven (1983:96) states that Judith, in 11:5-19 mocks Holofernes in her ironical deception. She mocks the self-image of her opponent just as the Lord mocks the arrogance of the haughty Assyrians in Isa. 10:13. She eventually succeeds by killing Holofernes and eventually defeats his army. God's intervention makes the victory possible for Judith. Therefore, Holofernes was not as strong and unstoppable as he appeared to be. Only God and the author and/or editor of the story know his weakness, which is, alcohol and women (sexual immorality).

Kanonge (2009:176) states that only the Lord God of Israel knows the truth and falsehood. The victory achieved by Judith reveals the truth concerning the contest between the God of Israel and Nebuchadnezzar (the deity of the Assyrian cult). Her actions and conduct in particular, even in the face of danger, exposed the falsehood of the Assyrians (Cohen 1989:51). The God of the Jewish religion is the true God and the king of the whole world. Raja (1998:696) also asserts that the God of Israel cares for his own people, especially in time of distress (see also Exod. 3:7-14). Nebuchadnezzar and the Assyrian cult are falsehoods and therefore cannot be accepted by God's covenantal people (see also Wennel 2007:68).

Judith's song of praise (together with rest of the Israelites) in Chapter 16 acknowledges that even when the Assyrian cult appeared to be strong and unstoppable, it was nothing compared to God's protective power over Israel. In this song, the author makes it a point that the message is clear even to other nations who might attempt to invade the Jewish religion in the future. In 16:17 the text records:

[Woe to the nations who will rise up against my nation. The Lord almighty will take vengeance against them in the Day of Judgment, in putting fire and worms in their flesh and they shall weep in feeling them forever.]

Furthermore, the author seems to suggest that the message in the above quotation is heard and well understood by all the people and nations around Israel. The story, in 16:25, closes by reporting that there was no one that made the children of Israel afraid and/or threatened them any more in the days of Judith nor a long time after her death.

This manner of concluding a story has a rhetoric intent. It has the power to persuade the reader. As alluded to earlier in this article, conclusions of this nature in the story possess the power, not only to reveal realities and prevailing worldviews but also to create new realities and new worldviews. The secret has been unleashed and the illusions have been exposed and refuted. The falsehood has been crashed and the truth has been affirmed.

In summary, this section focused on the application of the veridictory square to investigate truth and falsehood in Judith. The main aim was to attempt to discover the truth that the author desired to affirm and the falsehood that he wanted to oppose or expose through the narrative.

Conclusion

The aim of the article was to investigate the occurrence of truth and falsehood in Judith using the thematic level of analysis, the veridictory square in particular, as informed by the Greimassian semiotic approach. The point of contest centred on the observation that narratives are not neutral in their rhetorical intent. They are either meant to promote and/or endorse a particular worldview or oppose and/or refute an unwanted conduct and/or conviction within a particular community. The story of Judith was investigated in this way and the investigation proved to be unique and intuitive.

The findings as mapped out in the semiotic square of veridiction shows that Judith contains, in its many scenes, veridictory modalities: être and paraître (being and seeming/ appearing).

In the first place, the article established that in the first part of the story (Chapters 1-7), the construction of the persuasive truth concerning the Jewish religion and the Assyrian cult is based on appearance. The Assyrian cult appears to be powerful and unstoppable. Nebuchadnezzar appears and/ or seems (paraître) indeed to be the lord of the whole earth, but this was not the case (falsehood). It is only an illusion that Holofernes will destroy all the nations and subdue them. Furthermore, the Jewish religion appears to be weak and defenceless.

The investigation of the persuasive strategy in the second part of the story (Chapters 8-16), established that truth is based on être (being) and is advocated by the character of Judith. Judith was the secret weapon unleashed by the author and/or editor to go all out to prove that the God of Israel is the true God. She proves that Holofernes was not as strong and unstoppable as he appeared to be.

The Judith narrative can, thus, be read as a story that is not neutral in its intent. The persuasive strategy of communication in the story shifts from 'Assyrian religious claims' or 'falsehood' (Nebuchadnezzar claims to be a true god) to truth (The God of the Jewish religion is the true God).

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationships which may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

References

Cohen, S.J.D., 1989, From the Maccabees to the Mishnah. Westminster John Knox Press, Louisville, KY. [ Links ]

Courtes, J., 1991, Analyse semiotique du discours: De l'enonce a l'enonciation, Hachette, Paris. [ Links ]

Courtes, J., 1995, Du lisible au visible, De Boeck University, Bruxelles. [ Links ]

Craven, T., 1983, Artistry and faith in the book of Judith. Scholar Press, Chico, CA. [ Links ]

Esler, P.F., 2002, 'Ludic history in the book of Judith: The reinvention of Israel identity?', Biblical Interpretation 10(2), 107-143. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/156851502760162780 [ Links ]

Everaert-Desmedt, N., 2007, Semiotique du recit, De Boeck, Bruxelles. [ Links ]

Grabbe, L.L., 2004, A history of the Jews and Judaism in the second temple period: A history of the Persian province of Judah, T&T Clark International, London. [ Links ]

Greimas, J.A. & Courtes, J., 1979, Semiotique, Dictionnaire Raisonne du Langage, Hachette, Paris. [ Links ]

Greimas, J.A. & Courtes, J., 1982, Semiotics and language: An analytical dictionary. University Press, Bloomington, IN. [ Links ]

Harrington, D.J., 1999, Invitation to the Apocrypha, Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Hobyane, R.S., 2012, 'A Greimassian semiotic analysis of Judith', DLit et Phil dissertation, School of Ancient Language and Text Studies, North-West University, Potchefstroom. [ Links ]

Hobyane, R.S., 2014, 'The compositional/narrative structure of Judith: A Greimassian perspective', Old Testament Essays 27(3), 896-912. [ Links ]

Hobyane, R.S., 2015a, 'Canonical narrative schema: A key to understanding the victory discourse in Judith: A Greimassian contribution', Journal for Semitics 24(2), 638-656. [ Links ]

Hobyane, R.S., 2015b, 'Actantial model of Judith, A key to unlocking its possible purpose: A Greimassian contribution', Old Testament Essays 28(2), 371-394. http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2015/V28N2A9 [ Links ]

Kaiser, O., 2004, The Old Testament Apocrypha. An Introduction, Hendricksen, Peabody,MA. [ Links ]

Kanonge, D.M., 2009, 'The emergence of women in the LXX Apocrypha', PhD Thesis, NWU, Potchefstroom. [ Links ]

Levine, A., 1992, 'Sacrifice and salvation: Otherness and domestication in the book of Judith', in J.C. Vanderkam (ed.), No one spoke Ill of her: Essays on Judith, pp. 31-46, Society of Biblical Literature, Atlanta, GA. [ Links ]

Martin, B. & Ringham, F., 2000, Dictionary of semiotics, Cassel, London. [ Links ]

Moore, C.A., 1992, 'Why wasn't the book of Judith included in the Hebrew Bible?', in J.C. Vanderkam (ed.), No one spoke Ill of her: Essays on Judith, pp. 61-71, Society of Biblical Literature, Atlanta, GA. [ Links ]

Nickelsburg, G.W., 2005, Jewish literature between the Bible and the Mishnah, 2nd edn., Fortress, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Raja, R.J., 1998, 'Judith', in W.R. Farmer (ed.), The international Bible commentary: A catholic and ecumenical commentary for the twenty-first century, pp. 696-706, The Liturgical Press, Collegeville, PA. [ Links ]

Ralphs, A., 1996. Septuaginta: With morphology, Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart. [ Links ]

Roitman, A.D., 1992, 'Achior in the book of Judith: His role and significance', in J.C. Vanderkam (ed.), No one spoke ill of her: Essays on 'Judith', pp. 31-46, Society of Biblical Literature, Atlanta, GA. [ Links ]

Taylor, J.M. & Van Every, E.J., 1999. The emergent organization: Communication as its site on surface, Routledge, London. [ Links ]

Wennel, K.J., 2007, Jesus and land: Sacred and social space in second temple period, Clark, London. [ Links ]

White, S.A., 1992, 'In the steps of Jael and Deborah: Judith as heroine', in J.C. Vanderkam (ed.), No one spoke ill of her: Essays on Judith, pp. 5-16, Scholars Press, Atlanta, GA. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Risimati Synod Hobyane

risimati.hobyane@nwu.ac.za

Received: 18 Jan. 2016

Accepted: 04 May 2016

Published: 26 Aug. 2016

1 The term 'Jew' is used inclusively to refer to men, women and non-Jews (by birth) who trust in the God of Israel and observe the Law of Moses. A good example in the story of Judith would be Achior (cf. Grabbe 2004:167).

2 Italic font is for my own addition to that of Kanonge.

3 See Kanonge (2009:172) for detailed examples in this regard.

4 The Greek text of Judith quoted in this article is from the Septuaginta, edited by Alfred Ralphs and published by the Württenburg Bible Society's Press (1996).