Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

HTS Theological Studies

versión On-line ISSN 2072-8050

versión impresa ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.72 no.1 Pretoria 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v72i1.3501

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Imvuselelo: Embers of liberation in South Africa post-1994

Vuyani Vellem

Department of Dogmatics and Christian Ethics, Faculty of Theology, University of Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The unprecedented cultural consciousness after decades of black cultural suppression in the South African public life since the 1990s summons us to the need to harness African ecclesio-political symbols in public life. This task is executed at a time when the notions of inter alia, spirituality and Imvuselelo are at the heart of the combustion chambers of our public and political life. Imvuselelo is a thermometer of decolonialist rebellion - the militant spirituality linked with Tiyo Soga - and is a self-combustion escape route in instances of black African epistemicide and violence. The heuristic device of iziko (fireplace) is employed to illuminate and locate the re-establishment and anamnestic praxis of protological life-giving foundations of spirituality in the African universe in our interpretation of Imvuselelo. The notion of imvuselelo is illuminated through iziko to debunk the incompatibilities, disharmonies, incongruences and conflagrations of virtual spirituality in its capture and domestication of the resources of the downtrodden.

Introduction

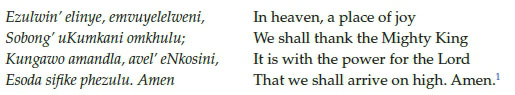

Since I met, knew and worked with Graham Duncan, he has become inseparable from Hymn 204 in the isiXhosa Hymnal of the Uniting Presbyterian Church in Southern Africa (UPCSA). Look at him when he sings this hymn by heart, particularly the last verse:

Graham sings this hymn by heart, with rhythm, verily in isidodana fashion to be precise, meaning, in the manner of the Men's Guild of the UPCSA, widely known as Amadodana across denominations. This rhythmic dance in song by someone who came young to South Africa from Scotland, one who became ordained in South Africa, epitomises how Scotland has continuously been 'taken out' of Graham as he has embraced some of the practices, almost literally so, that are quintessentially African both in his preaching, singing and, importantly, his intellectual life and interpretation of theology. This type of singing within the circles of Amadodana is associated with a liturgical form known as Imvuselelo; the subject of our conversation in this article is dedicated to Prof. Graham Duncan.

This article traces the roots of Imvuselelo to Tiyo Soga and thus seeks to argue that this liturgical form of worship, with its robust and vibrant features, is better understood as an expression of a decolonialist rebellion of faith. Proceeding to glance at the meaning of spirituality, the link between Imvuselelo and iziko (fireplace) is discussed to argue that as a sign of our times, the incompatibility of spiritual resources with their source of inspiration could be a deeper challenge in the context of the Empire. Since the adoption of the Accra Confession within the circles of the World Communion of Reformed Churches (WCRC), the concept of Empire has been a subject of debate and contestation. In this article, we follow this rendition of Empire:

We speak of empire, because we discern a coming together of economic, cultural, political and military power in our world today. This is constituted by a reality and a spirit of lordless domination, created by humankind. An all-encompassing global reality serving, protecting and defending the interests of powerful corporations, nations, elites and privileged people, while exploiting creation, imperiously excludes, enslaves and even sacrifices humanity. It is a pervasive spirit of destructive self-interest, even greed - the worship of money, goods and possessions; the gospel of consumerism, proclaimed through powerful propaganda and religiously justified, believed and followed. It is a colonisation of consciousness, values and notions of human life by the imperial logic; a spirit lacking compassionate justice and showing contemptuous disregard for the gifts of creation and the household of life. (Boesak, Weusmann & Amjad-Ali 2010:23)

The fusion of spheres and the collapse of the tension that differentiates them while bonded together, defended militaristically, creates a spirit of lordless domination, pervasive and destructive to life as it also colonises consciousness. For this reason, the article moves on to examine the relationship between power configurations of Empire and spirituality, concluding by identifying the locus of Imvuselelo as the Miserabili Dictu, - the coals of restlessness in a life-killing context.

Imvuselelo

Imvuselelo is a form of liturgy that is distinct from the traditional, conventional one. Although a minister, for example, may open the service of Imvuselelo, this form of liturgy distinguishes itself in many ways as ordinary members take part in preaching and share equally in the proceedings of the service. It is a dialogical celebration of worship. It is not a monologue. In this liturgical service home-made instruments, drums, imibhobho (literally hose pipes that are artistically used during singing by blowing through them), imisimbithi (rods) and many others, are used. The act of worship is boisterous with African style and flair. Imvuselelo in one sentence is a space in which liturgy and theology meet and in this case, black African theology.

The significance of this liturgical artistry, fused with black African aesthetics is that it could be traced to Tiyo Soga, the first black ordained minister in South Africa. Gideon Khabela says Tiyo Soga introduced 'a form of singing that carried the heartbeat and mood of (sic) Xhosa' (1996:34):

He utilised tribal songs, dances, stories, poetry that continued to exist independently of mission influence, transformed their meaning and recast them in the new framework that in essence created a new universe. (Khabela 1996:34)

That Khabela brings this point about the transformation of the meaning of the gospel by harnessing black African arts, is even more crucial when we consider Soga's response to the theory of the 'extinction of the African race', which sowed seeds for the development of Soga's 'militant spirit' (1996:32-33). These attributes associated with Tiyo Soga are appropriate for a deeper grasp of what Imvuselelo means and our assumptions in this article.

As the first black minister, Tiyo Soga, harnessing African songs, poetry, dance and stories to appropriate the meaning of the gospel in the context of the battle between colonial, missionary culture and isiXhosa culture, Imvuselelo could be reasonably interpreted as part of the heritage of black theology of liberation bequeathed by the father of blackness and Africanity in South Africa.2 It is a militant liturgical endeavour conceived when views about not only the extinction of the African race where dominant, but also black African epistemicide. Imvuselelo is an isiXhosa word or concept which loosely means revival or renewal. The verb ukuvusa means to revive, to awaken. The word has so many connotations in isiXhosa, ranging to erotic significations with some of its permutations, but it is also very deep as it is the same word or possibly its root once again that connotes resurrection, anastasis, uvuko! It is quite fascinating that this word, and here in its particular relationship with resurrection, carries an import of rebellion too.3 For example, ukuvukela umbuso, meaning to rebel against a kingdom, yes, to go against power. Imvuselelo could be used to signify the revival of imagination, rationality and spirituality in its various permutations of its root or verb form ukuvusa! It is a word that carries the import of energy. Enough of isiXhosa etymology for now, what we need keeping in mind for our conversation in this article is one well-known saying that 'it takes one coal from a neighbour's fireplace to revive another neighbour's fire place'.

The use of Imvuselelo is prismatic in this article - an image of Imvuselelo as a liturgical concept that carries verbs of revival, rebellion, energy in the struggle for life in times of oppression, even in post-1994 South Africa and the globalising world. The argument of this article is that it is in the embers, ashes or residues of Imvuselelo, traced to iziko, (fireplace) that our liberation spirituality could be found.

In the context of 'state capture' and the domestication of faith, the origins of this liturgical form and its relationship with Tiyo Soga, posit Imvuseleo within the Ethiopian spirit - a liberating artefact of spirituality - the foundations of black theology of liberation. In line with Frantz Fanon, we grasp our conversation through Imvuselelo in this manner:

Another way in which the native copes with the oppression of colonialism is in dance that, in its intensity, resembles possession by otherworldly spirits. Any anthropological study of a native population held in the grip of colonialism should pay careful attention to these dances, Fanon says, because they are an indicator, a thermometer, that measures the level of frustration and how close to the boiling point it has reached. (2013:8 of 20)

The robust singing, dance and ecstatic expressions, yelling, shouting and spending the whole night in worship, typical of an Imvuselelo service, surely must be about coping with oppression, a thermometer to measure the sanity of an oppressed people. These dances bear anthropological significance in contexts of oppression and humiliation as the case is in our South African history. Imvuselelo is indeed a liturgical thermometer to measure the intensity of the clash of two worlds resulting in the dispossession of our land as blacks and our cultural oppression - cultural oppression, which a la Gutierrez, is worse than death itself. Imvuselelo as a liturgical, cultural thermometer - a measure too of the extent of epistemicide (see Grosfoguel 2013:86), in the history that is fraught with genocides and ecocides that have hitherto shaped our black African experience and knowledge 'prismatically' suggests a resurrection, a rebellion for life. Imvuslelo is a prismatic symbol for a spirituality of a 'decolonialist rebellion' (Fanon, cf. BookRags Summary, The Wretched of the Earth 2013:1 of 5).

The problem that we give attention to then in this article is that this notion of Imvuselelo has now gained political currency in public life, and it is employed by the African National Congress (ANC) to designate a programme of the renewal and revival of the ANC's structures. Clearly when the ANC harnesses this artefact - Imvuselelo - the focus is on the political renewal and revival of its structures. Imvuselelo, however, carries profound theological connotations in its roots. To reiterate, it is a liturgical form of Christian service popular among the black Africans both in the so-called mainline churches including the African Initiated Churches (AICs) in South Africa.

It is a relic of homegrown symbols by ordinary people in the context of 'living death' on the mines, peripheries and now the dominant culture of globalisation consumed in neoliberal economics and democracy. Indeed as shown by the fact that Imvuslelo is a direct contrast of the formal liturgical orders inherited from the West, it remains an escape route for those held hostage in conditions of insanity.4Imvuselelo thus in its publicity reflects and refracts an endeavour to express, profess, confirm and celebrate faith in a truly African manner in throttling liturgical spaces that have little to offer for a black African person and pseudo-liturgical spaces of virtual spirituality in the age of informatics.

The ANC's use of this notion for the revival of its structures is ironic when we remember that the connection of the ANC with morality and spirituality has a long history. The ANC was referred to, at one stage, as 'a moral and spiritual force' in the quest for the liberation of black people (Spong & Mayson 1993:14).

Indeed in our times it has become even fashionable to refer to the ANC as 'a broad church'. Imvuslelo is thus a significant ecclesio-political symbol we cannot overlook for the task of black public theology of liberation today. It integrates the spiritual and the political. Public life, as this article contends, is equally a spiritual affair.

The rampant divorce of the spiritual from the political in public life today is subtle and deep, as the political and the economic seem to domesticate liturgical symbols thus usurping the space devoted for the worship of God. Any exaggerated emphasis laid on the political even the economic when symbols such as Imvuselelo are tamed - 'captured' to employ the current terminology - by positing political dreams or economic ones as equal to the comprehensive promises and significations of Imvuselelo, points undoubtedly to a struggle of the gods and God in public life and the globe. In this context of the domestication and capture of spiritual resources, the religio-political roots of Imvuselelo are therefore excavated. As a popular liturgical symbol, the article argues, Imvuselelo points to a particular kind of spirituality rooted among the masses for social revolution, renewal and revival, inspired by God's kerugma of the good news of liberation in repressive and oppressive conditions. Imvuselelo, we posit, thus points to struggles of disalienation embroiled within 'a zone of nonbeing' fraight with contradictions of virtual reality in which 'a black man is not a man' according to Fanon (1967:3 of 13). Fanon goes on to say (1967):

Zealousness is the arm par excellence of the powerless. Those who heat the iron to hammer it immediately into a tool. We would like to heat the carcass of man and leave. Perhaps this would result in Man's keeping the fire burning by self-combustion. (p. 5 of 13)

Cautious of zealousness as ominous of self-destruction and self-comsbition, Imvuselelo and indeed zeal should be viewed as the arm of the powerless, their own homegrown and self-made fireplace and combustion chamber in the heat of the struggle, albeit with contradiction and ambivalence in our context today.

Spirituality and Imvuselelo

Defining spirituality is notoriously difficult.5 It is, however, also difficult to avoid a simple description of what this construct entails. Let us take our cue from Kalilombe (1994:115) who describes spirituality as 'those attitudes and beliefs and practices which animate people's lives and help them to reach out toward super-sensible realities'. The connotation of the word 'animate' in this description is extremely important. To animate has among others a deeper connotation of 'enlivening', meaning; to make alive. To make alive the connection with super-sensible realities could be one way of looking at spirituality. It, in this sense, carries the import of 'inspiration'. The ideas of 'making alive' and 'inspiration' in relation to attitudes, beliefs and practices that are meant to facilitate reaching out to 'super-sensible' realms of life, or to connect with the super-sensible, constitute the subliminal theme that guides our attempt to conceptualise spirituality and its pertinence for publicity.6

These attitudes, beliefs and practices are what we could designate 'spiritual assets' or spiritual resources that keep people alive, 'coals' that burn in a 'fireplace' of our public life. These attitudes, beliefs and practices associated with Africans are, theologically speaking, the locus of the praxis of protological acts that re-establish a la Bujo (2003), inspire, communicate and enliven super-sensible experiences of the innermost person with God or a transcendental power in harmony with publicity.

One does not need to enumerate such practices and attitudes in our public life as they are countless and pervasive.7 The animation and enlivening of these spiritual assets or sources, such as those inspired by Imvuselelo for the functionalisation of publicity for political and economic ends instead of God, point to the danger of the domestication - the 'capture' - of spiritual assets or resources in public life.

To inspire and animate these beliefs and attitudes should have their goal to connect publicity rather with the super-sensible or God - the balance of the innermost thoughts and feelings with the public. To domesticate and 'capture' these resources for false reasons - the resources of Imvuselelo - are reminiscent of the powerful themselves, capturing and domesticating fire by self-combustion. For example, when the ANC uses Imvuselelo to revive its branches there is nothing wrong with that in our view. When in the use of Imvuselelo, the ANC detaches its political vision from the demands of the 'God of Imvuselelo'; then there is a huge problem. The distinction between self-combustion by the powerless and the same by the powerful is important to maintain. As we proceed with this conversation, we need to keep in mind the widely accepted view of the spiritual connectedness - integrated-ness and conviviality of life - among Africans.

The iziko, which is a part of ikhaya - the hearth of a home - is the fireplace that 'warms' up the connectedness of spheres in a home. Iziko could be prismatically viewed as the source for a spirituality that animates the connectedness of the spheres of a home and thus the connectedness of the innermost being with the super-sensible. Indeed, it is around iziko that the attitudes, beliefs and practices feeding our black African spirituality are placed; heuristically speaking.

In typical African cosmology and our interpretation of isiXhosa, Imvuselelo then evokes the workings of iziko, the fireplace. Imvuselelo in this regard suggests 'reviving', 'awakening', 'energising', 'resurrecting' iziko whose role is to warm practices, beliefs and rituals that are the spiritual resources of a home. With this in mind, iziko, as the energy source of Imvuselelo, speaks to the compatibility and proportion of the sources of spirituality and spirituality itself. There must be a balance between Imvuselelo and iziko.

According to Albert Nolan (2006) spirituality is a sign of our times. He (2006) says:

In our present circumstances of uncertainty and insecurity, spirituality could be seen as yet another form of escape. While this may be true in some cases, it seems to me that by and large the new search for spirituality, the deep hunger for spirituality, is genuine and sincere. It is one of the signs of our times. (pp. 7-8)

Nolan continues:

The sign, however, is not the number of people who have found a satisfactory form of spirituality to live by. Some have done so, but the sign is rather the widespread hunger for spirituality, the search for spirituality, the felt need for spirituality. (2006:7-8)

No doubt, escapism and hunger for spirituality are serious challenges for our day. The importance of spirituality as a sign of our times implies that we need to be bold and delve deeper into the workings of the current world briefly in order to account for this widespread spiritual hunger in the light of the problems of domestication or 'capture' of spiritual resources.

How, then, does the world use the 'thermometer', of the powerless, Imvuselelo, by producing its own fire in iziko for the combustion of our public life? We need to establish what the imbalances are between Imvuselelo and iziko, the incompatibilities and their dangers.

Empire and spirituality

What is this escapism and spiritual hunger in the context of Empire? What is this zealousness for spiritual hunger in Empire? What does this mean - escapism through self-combustion or hunger for self-combustion in Empire? Violence indeed! This hunger to heat the iron in order to hammer it as a sign of our times needs reckoning with what is happening out there - outside the innermost feelings of a human being, what we described as spirituality. Winks (1984:5) poignantly argues that in addition to the workings of the innermost feelings, the innermost yearnings that must be warmed up, that must be nourished and harmonised by those beliefs, practices and rituals symbolised for us by the workings of iziko, there are external forces too that are directly related to the configuration of structures and powers with which the innermost being constantly contends and should be in harmony with. Societal structures and powers, to employ another concept, have their own fetish. A fetish is a spirit, a dangerous one exhibited by structures of tyrannical power. The current world and its economic structures exhibit its own spirit.

The Church of England's General Synod 2009 report on the financial crisis was summarised this way:

The dominant assumptions in our economic system may be innately un-Christian - assuming that human beings are strangers who relate to one another only with the aim of maximising profits and pleasure. Economics is not simply a science for experts. It contains assumptions about the nature of human beings, which is a moral and theological question. (Wallis 2013:10 of 36)

There is something innately un-Christian about our economic order in the world today. Proceeding from this point, namely that the current economic order is un-Christian, even though it has assumptions about the nature of human beings, we may need to ask what the spirituality of this order is. According to the Accra Confession (2004), the current world order is life killing. We live in a world in which the unprecedented convergence of the military, the political, the economic and cultural spheres is a matter of life or death. Article (14) of the Accra Confession states:

We see the dramatic convergence of the economic crisis with the integration of economic globalisation and geopolitics backed by neo-liberal ideology. This is a global system that defends and protects the interests of the powerful. It affects and captivates us all. Further, in biblical terms such a system of wealth accumulation at the expense of the poor is seen as unfaithful to God and responsible for preventable human suffering and is called Mammon. Jesus has told us that we cannot serve both God and Mammon. (Reformed World, Vol 54, No 3-4, p. 171)

If this global system captivates us all and protects the interests of the rich, symmetrically opposed to the teachings of the gospel, how then do we explain rather than describe its corresponding spirituality? Yong-Bok Kim (2007) further explains the workings of the current order in this manner:

The global signs of our times are found in the symbiosis of the global economic regime (globalisation) and the global empire, together with the convergence of advanced sciences and technologies.… The signs point to an unprecedented global trend, toward the total destruction of life on earth by these multi-dimensional, interrelated powers. Such a 'totalistic' trend - be it geo-political, economic or ecological - is unheard of in history. (pp. 2-3)

In resonance with this toxic symbiosis of the global order of economics, Leonardo Boff (2014) says:

Another factor in globalization consists in the hunger and thirst for spirituality, in the meditation about the meaning of life, and about the crucial meaning of this technological adventure which human beings have undertaken for the past 400 years. (p. 13 of 20)

Boff affirms not only what Nolan said above, but also helps explain this symbiosis of science and technology in the world today, which is mediated through spirituality for the meaning of life. Yet, Empire is, as we have already said, life killing. The interrelated powers of Empire, totalistic and destructive, produce a particular kind of spirituality that is clearly anti-life.

The domestication of spiritual assets therefore could be tantamount to the animation of the protological acts of spirituality, in iziko, as a function of the symbiotic order of the political, economic and cultural towards the total destruction of life, which is the crux of our argument. But where do we locate this? The world has shifted into informatics. Informatics simply means the collection of information that constitutes anything on earth into bytes. 'All beings, alive or not, are the carriers of particular data that can be assessed and measured in bytes, (binary digit), and stored in computers' (Boff 2014:2 of 35).

Accordingly, computer science and robotics are paradigms of knowledge that equally exhibit their own spirit. What Boff says in this regard is important: 'Informatics increasingly does away with human labour' because production becomes cheap. In a world where production is cheap and even better in some instances without needing massive human labour, the shift has become much more related to the distribution and thus the selling of the product. So, while it is cheap and fast to produce, it is difficult to sell.

Marketing is now the central locus of our challenges in this world. The question is 'How do we arouse needs in consumers?' (Vellem 2012).8 Cultural goods, cinema, music, photography, design and fashion are among the aspects that are tamed to produce images of marketing that arouse the need in consumers. Most of these are simply 'wants' in economic terms, but they are driven and imaged as 'needs'. Boff (2014) says:

Our individual personal identity is increasingly the projection of our own particular image in society. It now has less to do with one's inner self, the dialogue that lies within, and how we mediate the inner and external worlds we inhabit. One either takes part in this world-show in a direct manner, as participant actor, or indirectly through imagination and images. (11 of 34)

The world has become a big theatre and human beings are not real actors but virtual actors as they participate mostly through imagination and images. Virtual image is the crux of the matter here. To arouse the needs of the consumer in marketing is tantamount to creating images that are virtual and not really, simultaneously altered as needs rather than wants. The success of this order is in zealously feeding the desire through images, ipso facto, the combustion of marketing images for virtual spiritual hunger as it is actually caused by arousing the desire for need.

Virtual spirituality attacks iziko, the hub of spirituality and the heart of Imvuselelo. It distorts and subverts the coal that must be used in iziko. Pasewark says that 'power is the communication of efficacy which posits itself at the borders between beings' (1993:220), which means that power is created at the intersection of inwardness and externality. Pasewark's motivation for the use of the notion of communication stems out of the fact that the term communication stresses 'the in-between nature of power' (1993:219). This definition of power is profound, not only because it is a theological attempt to chart the geography of power. It is also profound because it can explain what takes place at the terrain of spirituality. It can explain the dissonance between inwardness and externality. As Boff argues, spirituality is the capacity of human beings to connect their inner most thoughts, entering into harmony with their innermost pleas. This connection requires equal harmony with the exterior. Sometimes even if this interior harmony is achieved, the exterior disharmony can easily disrupt and even rupture it. Communication at the borders between the innermost harmony and the exterior harmony of the powers of the structures can only be efficacious if it produces life. Virtual spirituality is the disequilibrium of the in-between power with fatal ruptures.

This disequilibrium happens in the inward part: iziko! Iziko, the source of energy, power, dynamism and the vibrant communal life that is communicated in an African home to maintain harmony and to affirm life, miscommunicates with the 'coals'. The convergence and unprecedented symbiosis of the differentiated spheres of public life, as we have already noted above, propelled through virtual images, equally causes an unprecedented spiritual disharmony. It fragments the harmony, equanimity and conviviality of the inner most being and the exterior. The force-fields in between the innermost and the exterior are undermined by usurping the spiritual resources ultimately dislocating them from their place of abode or extricated from their dwelling place.

What is even worse is that the fragmentation, convergence or a malignant symbiosis of differentiated spheres begets a deadly conflagration - zeal and self-combustion.

Mirabile Dictu: The Iziko (fireplace) of Imvuselelo

To plumb the notion of Imvuselelo in public life we evoke the workings of the Aristotelian politike koinonia. We posit it in our African heritage, for example, in the saying that umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu (I am because we are). In the context of Empire, 'I am a political being because we are political beings' is disobeyed and destroyed by the configuration of power which distorts need and want through virtual image. Zoon political means a living political being. Zoe means life and zoon is a being derivative of zoe. The political community is a living being. Virtual spirituality which occurs when there is disequilibrium in the force-field between the innermost being and the exterior destroys life by creating virtual zoon political - robotic beings and deadly weapons of war. If spirituality is spiritual life, democracy is challenged to give expression to the historisation of the spirit of this interstice - Tiyo Soga's interstice in the context of the ideas of the extinction of Africa. Its truthfulness depends on the life of the poor which inserts spirituality to the bonds of publicity and people within history. The spirit of fidelity (cf. Sobrino 1988) is the spirit of openness (porosity) and causes this irruption or porosity in polity structures that find expression in public life. Fides means honesty: trustworthiness. It is honesty and trustworthiness about reality. Fidelity to the disemboweled not virtual images and democracy, is the meaning of Imvuselelo.

Imvuselelo is rebellion in worship. It is resurrection in the context of death in the coloniality of the oppressed and rejected. Imvuselelo is a rich, dangerous memory of restlessness and insanity in the midst of oppression. Imvuselelo is a rich, impatient, militant, insurgent and dangerous memory of the spirit that refuses to be relegated to the grave and the hillside. Imvuselelo is the revival of home for the indwelling of the spirit of liberation. Imvuselelo is the arch, arché of the breath of life, the ruach of life in the face of the tangent of death. Arche should be read as the architecture of the spirituality of liberation. Imvuselelo is the arch of solidarity of the shaken. Imvuselelo is to unlearn to die the death of a slave, cheap labourer. It is a spirit of governance - a reign and rule of a great spirit in the dungeons of oppression. Spirituality as related to tradition is the repetition, the 'routinisation' of an experience tested through the blood of the people in order for life to be abundant. Spirituality means handing down that great spirit of the traditions of value and worth. It means imbibing and drinking from the well of the 'restless memory' that needs to be inserted in the remaking of our public life. It is the fireplace (iziko) of value and worth in restlessness. Such a tradition to be routinised is Tiyo Soga's spirit, the ancestor of black consciousness and African identity.

Conclusion

The embers of our liberation are in Imvuselelo, the article argued. The zeal and vibrancy of Imvuselelo, present the latter as a liturgy that is an expression of a narrative of coping from within the vagrancies of black African extinction since conquest, colonialism and Christianisation. It is a liturgy of a militant spirit, coming down from Tiyo Soga into our moment of decolonisation today. As a vital liturgical thermometer in times of state capture and the domestication of faith, we can only reclaim this liturgy and the zeal of the powerless to rebel against the virtual spirituality of Empire with its fetishes that distort need and want in the images of the current world-show.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationships which may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

References

Boesak, A.A., 2015, Kairos, crisis, and global apartheid, Palgrave Macmillan, New York. [ Links ]

Boesak, A.A., Weusmann, J. & Amjad-Ali, C., 2010, Dreaming a different world-globalisation and justice for humanity and the earth, the challenge of the Accra confession for the churches dreaming a different world. Evangelisch-reformierte Kirche, Germany, Uniting Refromed Church in Southern Africa. [ Links ]

Boff, L., 2014, Global civilisation: Challenges to society and to Christianity, transl. A. Guilherme, Routledge, London. [ Links ]

BookRags Literature Study Guide, 2013, The wretched of the earth by Frantz Fanon. [ Links ]

Bujo, B., 2003, Foundations of an African ethic: Beyond the universal claims of western morality, Paulines, Nairobi. [ Links ]

Cohen, J.L. & Arato, A., 1995, Civil society and political theory, MIT, Cambridge, MA. [ Links ]

Fanon, F., 1967, Black skins, white masks, transl. R. Philcox, Grave Press, New York. [ Links ]

Grosfoguel, R., 2013, 'The structure of knowledge in westernised universities: Epistemic/racism/sexism and the four genocides/epistemicides of the long 16th century', Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge XI(1), 73-90. [ Links ]

Khabela, M.G., 1996, Tiyo Soga. The struggle of the Gods. A study in Christianity and the African culture, Alice, Lovedale. [ Links ]

Mamdani, M., 1996, Citizen and subject: Contemporary Africa and the legacy of late Colonialism, Princeton Studies in Culture/Power/History, Fountain, Kamapala. [ Links ]

Nolan, A., 2006, Jesus today. A spirituality of radical freedom, Double Story, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Pasewark, K.A., 1993, A theology of power: Beyond domination, Fortress, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Sobrino, J., 1988, Spirituality of Liberation, SCM, London. [ Links ]

Spong, B. & Mayson, C., 1993, Come celebrate! Twenty five years of the South African Council of Churches, SACC, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Vellem, V.S., 2002, The quest for Ikhaya: The African concept of home in public life, Unpublished master's dissertation, University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

Vellem, V.S., 2010. 'Prophetic witness in black theology - With special reference to the Kairos document', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 66(1), Art. #800, 6 pages. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v66i1.800 [ Links ]

Vellem, V.S., 2012, 'The opiate of neoliberal globalisation and the dawn of democracy in South Africa', Theologia Viatorum 36(1), 76-93. [ Links ]

Wallis, J., 2013, God's economics: Principles for fixing our financial crisis, Brazos Press, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Winks, W., 1984, Naming the Powers: The Language of Power in the New Testament, Fortress Press, Philadelphia. [ Links ]

Yong-Bok, K., 2007, 'A fresh attempt at theological reflection in the global context - An Asian perspective' paper presnted at the 2007 WCC-CWM Conference of theologians, Seol Korea, August 12-17. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Vuyani Vellem,

vuyani.vellem@up.ac.za

Received: 23 May 2016

Accepted: 18 Aug. 2016

Published: 28 Nov. 2016

Project leader: V.S. Vellem

Project lumber: 04425030

1 Author's own translation of the verse.

2 It is important to remember that Tiyo Soga is regarded as the 'father' of black and African theologies.

3 Allan Boesak (2015:30) in his book Kairos, Crisis, And Global Apartheid: Challenge to Prophetic Resistance: New York: Palgrave Macmillan most recently, and poignantly so, argued that resurrection is rebellion.

4 This idea could be found in the concept of mokhukhu. See how it is conceptualised in Vellem (2010).

5 I am making this assertion out of my vivid memory of a vigorous debate on spirituality during my seminary days. At The Federal Theological Seminary (Fedsem) there were different traditions that held equally different views on the subject. Whilst there was a developed course on spirituality, there were those who felt the need to teach this subject across all the traditions that were present on campus while others felt that spirituality could not be taught.

6 Publicity is used in a technical sense. It used to designate differentiated publics in modern civil society. Compare Cohen and Arato's use of the term (1995:155) to signify 'the norms and organisational principles of modern civil society, from the idea of rights to principles of autonomous association and free horisontal publicity'. Mamdani (1996:14) uses the term 'free publicity' to refer to the public sphere as an arena of contested meanings.

7 It is a common spectacle for politicians to visit Moria, Shembe, Temples and kraals during important times such as elections. The use of the notion of 'church' in relation to the ANC is also common in our public life. Singing and dancing in huge conferences of political parties is a common feature. The presence of such spiritual assets in important processes such as the Truth and Reconciliation is common knowledge in our public life.

8 In this article, the fundamentals of Francis Fukuyama's economics are discussed and the use of the AIC's dance, music and uniform in a telling advert. Accordingly, Fukuyama's triumphalist view of the current economic order is based on the confusion that capitalism has created between a 'want' and a 'need'. To drive the desire of a consumer, 'wants' are changed into 'needs'.