Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

HTS Theological Studies

versión On-line ISSN 2072-8050

versión impresa ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.71 no.2 Pretoria 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v71i2.3032

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Compassion fatigue: Spiritual exhaustion and the cost of caring in the pastoral ministry. Towards a 'pastoral diagnosis' in caregiving

Daniël Louw

Department of Practical Theology, Faculty of Theology, Stellenbosch University, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The pastoral ministry of caregiving inevitably implies a cost. The spiritual ethos in the Christian ministry implies a huge sacrifice. Dietrich Bonhoeffer (see footnote 9 in the article) described this ethos as 'the cost of discipleship'. Very specifically in the case of unexpected and the so-called 'undeserved modes of suffering', the meaning framework of the caregiver is being interpenetrated, causing a kind of 'depleted sense of being'. It is argued here that an appropriate diagnosis, and a description of the phenomenon of compassion fatigue, can help caregivers to better understand their sense of being depleted. Instead of leaving the pastoral ministry, this can help them to attend anew to their spiritual capacity. In this regard, a theology of compassion, framed by theopaschitic theology, can help pastors to become 'healed' in order to re-enter the pastoral ministry and regain a sense of parrhēsia.

Introduction

It was C.R. Figley (1955) who came up with the central thesis that there is inevitably a cost to caring. To be exposed to stories of fear, horror, violence, hijacking and painful experiences of other people, trauma can backfire on the caring system and create a kind of spiritual exhaustion or 'caregiving trauma'. Caregivers may then suffer from an over-exposure to trauma and develop 'compassion fatigue'. Figley (2002:3) explains, 'it is obvious that we can be traumatised by helping suffering people in harm's way as well as by being in harm's way ourselves'.

How then should one understand the connection between compassion fatigue and the spiritual tension experienced by caregivers? Despite communalities, is there a qualitative difference between compassion fatigue in the pastoral ministry and the same experiences in other helping professions? If these are indeed the same, what is the unique emphasis in pastoral caregiving, and how does one cope with compassion fatigue within the liminality between life and death, healing and dying, meaning and non-sense? How does compassion fatigue influence existing theological models regarding the involvement of God in human suffering?

Compassion fatigue: Conceptualisation and paradigmatic clarity

Researchers are of the opinion that compassion fatigue1 is related to compassion stress, burnout2 secondary victimisation, co-victimisation, contact victimisation, vicarious victimisation, secondary survivor and emotional contagion. The fact is that the experience of trauma affects all of the people involved, including the support systems.

Whilst burnout refers more to exhaustion in terms of professional identity and a feeling of overwhelmed incompetence, Figley (1955:11-12) points out that compassion fatigue refers to exhaustion in terms of activity and input. Professionals suffering from burnout tend to become less empathetic and more withdrawn and end up considering a change of profession and the option of quitting. In the case of compassion fatigue the tendency is to continue to give oneself fully to the patient or traumatised persons, with an awareness of how difficult it is to maintain a healthy balance of empathy, engagement and objectivity (Pfifferling 2003:39-48).

It is indeed very difficult to differentiate between compassion fatigue3 and burnout. The two are interrelated to the same phenomenon of exhaustion and over-exposure. Both refer to reaction and attitude. The cause of burnout is accumulative stress, with the tendency to withdraw and to avoid being exposed. Compassion-fatigue is the result of excessive over-identification and constant exposure to severe forms of human suffering. Compassion fatigue tends to be the result of over-investment and a struggle with 'intertwinement'.4 However, in both cases the result is a raised state of stress and vulnerability, and what D. Capps (1993) calls the depleted self5 and the shameful self. The pathology in both is often a process of unrealistic self-inflation (Capps 1993:11). In order to cope with burnout, depletion and fatigue, self-therapy and personal repair become symptomatic of the pathology itself: 'the repair takes the form of doing more of what they had been doing, even though this was what got them into their current state of vulnerability' (Capps 1993:27).

Being exposed to trauma and violence necessarily implies that everyone who sees a disaster is, in some sense, a potential victim. The world in itself can become a traumatised environment (Neuman & Gamble 1995:341-347, 344). McCann and Pearlman (1990:31-149) point out that Jung was aware, in his research, of the impact of trauma on the care-giving system: an unconscious infection may result from working with the mentally ill. Conditions of depression and despair in one's clients and patients can be related to depression and is called: 'soul sadness'.

It is of paramount importance to clarify the concept. Confusion can even add up to pathology. Naming the issue in an appropriate way can contribute to spiritual health. By spiritual health is meant a constructive and clear understanding of the purpose, meaning, motivation and paradigmatic framework that determine the level of professional satisfaction and efficacy, as well as the quality of compassion competency.

Many people in helping professions, and especially caregivers, think they suffer from burnout and even burn-up resulting from 'bad stress'. This confusion hampers the efficacy and skilfulness of the helping profession. The confusion becomes even more intensified when the condition is diagnosed as a severe form of depression6. Although reactive depression could be one of the side-effects, it is important that diagnosis should be precise in order to come up with appropriate treatment of the condition.

My basic assumption is that compassion fatigue entails more than merely emotional or physical exhaustion. Compassion fatigue should be differentiated from burnout, burn-up (extreme form of burnout) and vicarious trauma (suffering on the behalf of the other). It entails more than merely inner depletion and emotional exhaustion. In pastoral caregiving with its focus on existential life questions, and the connection between transcendent meaning-issues and philosophical life views, compassion fatigue describes a kind of spiritual exhaustion within the interplay between being functions and inappropriate frameworks of meaning in life. Compassion fatigue in pastoral caregiving (besides the emotional and physical factor of exhaustion) describes fundamentally the barrier of spiritual exhaustion and its connection to depleted hope and an inappropriate theological framework of reference; it is about a kind of normal acknowledgement of personal limitation, helplessness and hopelessness within the realm of commitment, motivation and meaning-giving. The emphasis is on the quality of one's belief system, vocation, professional conviction and appropriate theological theory, normative framework, attitude and philosophy of life, as being more a qualitative and hermeneutical issue (level of meaning and interpretation: what is at stake here?) rather than a quantitative issue (level of input: how many?).

What then are the spiritual implications of compassion fatigue on hope care?

Liminality: Border-awareness within the in-between of life and death

Compassion fatigue surfaces within the awareness of liminality. On the threshold between life and death, hope and helplessness or hopelessness, compassion fatigue wrestles with own transience and woundedness. Compassion fatigue is to a certain extent an indication of a border-awareness: The boundaries and barriers set by inexplicable human suffering, pain and tragedy.

The concept liminality is connected to an awareness of threshold, margins and boundaries. The term limen refers originally to rituals that demarcate the passage from one life phase to another (Campbell & Cilliers 2012:40). 'Essentially, then, liminality implies an ambiguous phase between two situations or statuses. Often this in-between space is filled with potential or actual danger' (Campbell & Cilliers 2012:41). One becomes aware of possibly frightening borders and barriers that are difficult to overcome and to cross.

A 'border' is not merely about human limitation, a lack of capacity, a psychological or mental block, a cultural difference, inappropriate coping skills or the boundaries of a personal make-up. Borders are part of life and our experience of transience. Border-experiences are part of our being-in-this-world (Heidegger 1963: existentialia; structures of Dasein).

The most definite border and demarcation of life is death. Thus, the reason why M. Heidegger, in Sein und Zeit (1963), asserts that life should be understood within the limitations set by death7. A border is necessary because it sets off (Abgrenzung); it defines particularity and articulates demarcation. It deals with identity and, as an ontological category, provides a sense of hermeneutical framework in order to detect meaning in life and to understand the character of an issue or phenomenon. Borders help to differentiate between text and context. One can say that a border-awareness creates different spaces and articulates diversity. Borders cut one down to size and refer to the essence or design (Entwurf) and of being (So-sein; modes of being).

Borders are also categories of 'crises' (krinein: to separate wheat from chaff; krinō: to judge; to question and to separate, part, put asunder and distinguish). Borders as threshold-situations create opportunities for differentiation; a border can open up new avenues to gain clarity regarding what really counts in life. Borders are never definite but heuristic categories and frameworks for meaning within the dynamics of interpretation (Verstehen).

As a result of the fact that a border, as an existential category, deals with dying and estrangement, a border is related to the limitations set by relationships (a relational phenomenon) within the human predicament of transience, suffering and human failure and the experience of vulnerability and non-sense.

A border as a phenomenon of liminality (Begrenzt-sein) shapes us in several ways:

-

Identity and the human quest for dignity (ethos): Who am I? Can I cope with life and suffering? As a human being particularity, locality, time, historicity and space set specific limitations to identity. The problematic issue: failure and sense of incompetence.

-

The quest for meaning in suffering within the polarity of immanence-transcendence; ridiculous-sublime; transience-the Ultimate. Who is God? Can God cope with life and suffering? The problematic issue: theodicy8

-

Our awareness of helplessness and the need for 'signals of transcendence'. How can one deal with 'fate' and unavoidable boundaries in life? The problematic issue: hopelessness.

-

The challenge to heal and to care; to make a difference and enhance the quality of life: The quest for help and healing. What is care and how do I care within the awareness of transience and tragedy? The problematic issue is compassion.

With reference to the previous outline on the phenomena of 'border' and liminality as existential realities (Heidegger: existentialia), one can argue that spiritual exhaustion, and its connection to compassion fatigue, surfaces within the experience of border, liminality and paradox.

Spiritual exhaustion and the interplay between paradox, antinomy and polarity

As an existential exponent of spiritual exhaustion, the spiritual tension in compassion fatigue is related to three interrelated issues, namely: paradox, antinomy and polarity.

Compassion fatigue wrestles with contrast and contradiction within the awareness that a dialectical synthesis, or rational solution, regarding the meaning in suffering, would not alleviate the pain of the irreparable loss or the vulnerability of the sufferer's predicament. The fatigue manifests because caregivers are exposed to the pain of tragedy and irreparable loss. On the other hand, caregivers are exposed to their own spiritual borders of coping. But at the same time, they become painfully aware of the fact that, resulting from the spiritual and theological notion of calling and vocation, directed by the notion of 'costly grace' (Bonhoeffer 1959)9, they cannot merely quit and give up.

Therefore, compassion fatigue in pastoral ministry is about spiritual suffering at the brink of paradox, antinomy and polarity. Compassion fatigue grapples with the following contradictions on a spiritual level:

-

Paradox: The self-contradictory proposition that appears to be obviously absurd or nonsensical. The contradiction is about apparent, seemingly opposite factors that are maintained at the same time. As Paul asserts in 2 Corinthians 6:9-10, 'as unknown, and yet are well known; as dying, and see - we are alive; as punished, and yet not killed; as sorrowful, yet always rejoicing; as poor, yet making many rich; as having nothing, and yet possessing everything'.

-

Antinomy: This involves two contrasting perspectives regarding the same issue or object, each with a legitimate view. Each side is legitimate and equally tenable despite their seeming lack of reconciliation (the legitimacy of two equally tenable opposites). In an antinomy, both sides are substantiated by factual evidence. For this reason, one is compelled to accept both positions as legitimate (Hernandez 2012:3). On the one hand it seems in Scripture as if God is present in suffering. On the other hand, in the forsakenness of Christ, God the Son protests against all forms of human suffering and it seems as if God is absent. How can both be true at the same time? Somehow, God is against suffering as well as engaged in suffering. Two apparently contradictory ideas represent and convey two spiritual truths: Divine absence (forsakenness) and divine presence (comfort).

-

Polarity: This describes the dynamics and tension in reciprocity created between contrasting opposites. When two contrasting principles are placed side-by-side or invoked simultaneously, tension predictably arises. Two opposites within a dual tension are then maintained and accommodated at the same time as part of the reality at stake. For example, human beings are exposed to sin. However, if they transgress they will be pardoned due to the mercy and grace of God. Aware of grace, believers still continue to sin, knowing that they are guilty, but they will be forgiven when they confess.

In their attempt to come to grips with paradox, the awareness of incompetence affects spiritual resources and the ability to cope with the demands in pastoral ministry. The result is: a lack of spiritual resilience and a spiritual courage to be.

Lack of spiritual resilience

As said, compassion fatigue is closely related to the trauma of overexposure. However, it cuts deeper. It is fundamentally about the illness or spiritual pathology of 'professional disempowerment'. It is a condition related to the sickness of professional helplessness, and the fear not to be able to deal furthermore with human suffering in a sustainable way; it describes more or less a condition of habitual incompetence. In addition, this is of paramount importance: compassion fatigue does not primarily reside in a lack of skills (know how), but in a lack of resilience within the face of the desperate situation of human beings and the predicament of an overwhelming sense of failure and vulnerability. The question is not merely: can I cope? The question is: how do I proceed, and do I have the courage to be?

Compassion fatigue infiltrates the realm of the conative: motivation and commitment. It is in this regard that the notion of resilience surfaces. Psychology has identified and described the internal or psychosomatic ability to cope with external pressure, as a mode and habit of resilience (from the Latin resilire: rebound). It refers to the capacity of the will not to be hampered by the external barriers or pressure; it is about an attitude, not to be cast down, but to bounce back with inner strength and constructive, positive energy (fortigenetics).

Attitude in pastoral ministry is described as phronesis. The mind and attitude of pastoral caregivers are, according to Phillipians 2:5, directed by the mind (phronesis) of Christ, his humbleness and sense of sacrifice. Thus, my basic contention and assumption that in caregiving, compassion fatigue, in the pastoral ministry of caregiving, is closely related to the confusion between the affective dimension in compassion and the noetic and paradigmatic framework for compassion which is derived from the Christ-phronesis. In this regard, a God-image, fed by the notion of costly grace, can play a decisive role in spiritual exhaustion. This is also the reason why inappropriate God-images (for example the all-power concept of omnipotence - God as pantokrator) (Louw 2000) contributes to the condition of spiritual exhaustion. The spiritual reasoning develops: if God is all-powerful and does nothing to prevent disasters, I become disempowered as well; I feel helpless and overcome by suffering; I am spiritually impotent.

What one should keep in mind is that compassion fatigue infiltrates our theological paradigms and basic human quest for meaning; it becomes a kind of spiritual yearning for wholeness and human dignity resulting from an overwhelming, temporary affect of failure. Compassion fatigue actually blurs caregivers' long-term vision and efficient caring strategy. One can say that compassion fatigue develops as a by-product of the failure to 'see' the 'bigger picture'. One becomes particularly overwhelmed by the anxiety for the loss of skilfulness and significance that one goes temporarily on a spiritual strike. It seems as if technical, counselling skills or managerial skills seem to fail and that one is not equipped to meet the demands of human suffering in a sustainable way. This feeling of failure is then projected onto an 'impotent God' as well.

However, in a diagnostic approach to compassion fatigue in pastoral ministry, one should reckon with the fact, that the fatigue is not merely 'spiritual' on a noetic level, but also emotional and, thus, a psychological condition as well.

The connection: Compassion fatigue - burnout - vicarious suffering

Compassion fatigue, burnout and vicarious suffering have in common that they are all related to the affective component in caring and deal with the predicament of a kind of psycho-spiritual helplessness. Without any doubt, all three mentioned phenomena have a decisive impact on the physical, emotional and mental level of exhaustion. They all deal with exhaustion caused by a kind of psychological depletion; such as the psycho-physical inability to cope with the demands emerging from one's every day, existential environment.

Most of the time, the categories of compassion fatigue, burnout and vicarious suffering are viewed as exchangeable concepts (Figley 2002:1-14). However, although all of them are concerned with a mode of affective depletion, one should differentiate between them. This should be implemented in order to enhance a profound diagnostic description and, thus, contribute to spiritual healing within the helping professions: the so-called healing of the wounded healer.

Burnout is often described as a state of physical, emotional, and mental exhaustion caused by a depletion of ability to cope with one's everyday environment; it is a result of frustration, powerlessness and inability to achieve work goals (Valent 2002:14). It is closely linked with professionalism as the urge to perform always excellently in terms of the achievement ethics of pragmatism and functionalism.

One can say, between burnout and compassion fatigue, that there is a difference in terms of grade, not in terms of character and essence. Both involve levels of exhaustion. The difference resides in the fact that burnout refers more to over-performance resulting from doing functions and the pressure of achievement ethics resulting in performance anxiety and a sense of regular failure (being incompetent). On the other hand, compassion fatigue refers more to over-exposure resulting from acute sensitivity (over-empathising). As a result of depleted being functions and the trauma of being overwhelmed by the desperate situation of suffering (see the tsunami in Japan), a kind of nausea or negativity sets in. In compassion fatigue, the wounded healer now becomes the victim of being wounded by the wounds and pain of the other.

Without any doubt, compassion does affect the counsellor and cause harm in terms of attitude and aptitude. In the literature on the impact of working in a trauma unit, researchers work with the notion of 'vicarious traumatisation' (McCann & Pearlman 1990:139-153).

The danger, of becoming a victim of the sufferer's suffering, can be linked to the phenomenon of vicarious suffering, namely how the pain of the other becomes one's own pain and challenges one to start suffering on behalf of the other. Vicarious suffering is closely related to the fact that in Christian spirituality, one is called to the ethos of sacrificial ethics (costly grace). In order to help, one should be prepared to sacrifice one's own agenda for the sake of the other.

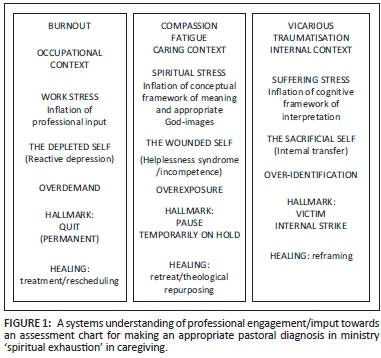

In Figure 110, the differentiation between compassion fatigue, burnout and vicarious suffering can be summarised as follows.

Burnout points more to the level of the professional identity regarding occupation and job demands; it is closely related to the work stress of the workaholic. The self becomes depleted resulting from an over demand on skills. Burnout often results in a kind of reactive depression with the intention to quit and the wish to rather do something else. Healing is primarily focused on medical treatment: the prescription of drugs. It also implies a rescheduling of an overloaded work schedule, perhaps even a change in terms of one's job and career (future planning).

Compassion fatigue points more to the level of spiritual stress because the pain and helplessness of the other infiltrates the caregiver's framework of meaning and conceptualisation of pain and suffering. The wounded self (healer) develops as a natural and normal reaction to overexposure resulting in the coping strategy to put everything temporarily on hold. Healing should be part of the normal procedure in caregiving, namely debriefing within the safe and quiet space of a retreat. Sharing with other caregivers in the field, and an opportunity to revisit one's theory and framework of meaning, helps to gain a kind of spiritual resilience, and perhaps a change towards a more appropriate God-image and new spiritual purpose (repurposing).

Continuous exposure to suffering affects one's whole being; especially one's attitude (habitus) and internal make-up and cognitive framework. Internal confusion and a kind of over identification (psychological impact resulting from being overwhelmed by the desperateness of people) leads to traumatic experiences; often irrational behaviour and a kind of obsession to help and to replace the suffering of the other. Vicarious suffering then points to the phenomenon of internal doubt (spiritual strike) and an intensified awareness of an anxiety for loss resulting from the inevitable fact of tragedy in life. Because of an over-identification with the predicament of the sufferer, one is easily exposed to the danger of becoming the victim of the trauma. Healing should focus on reframing; such as the attempt to revisit one's paradigmatic framework, patterns of thinking, commitments, convictions and belief systems and to re-evaluate and transform them within the light of existing challenges (change of meaning). Reframing is then about the attempt to change the conceptual and emotional setting or viewpoint in relation to which a situation is experienced, and to place it in another frame which fits the facts of the same concrete situation equally well or even belter, and thereby changes the entire meaning (Capps 1993:17). Reframing intends to out-manoeuvre the dysfunctional attitude of being a victim; it revisits the internal trauma that causes spiritual pain and discomfort, allowing creative energies to emerge instead (Figure 1).

In order to summarise the argument thus far, one can say: burnout and burn-up refer to overload and over demand resulting from quantity (too many demands at the same time with the attempt to try harder); compassion fatigue refers to overexposure resulting from quality (an acute awareness of the transience of life and the intensity of human suffering; the helplessness of the sufferer); vicarious traumatisation refers to over-identification resulting from a sacrificial ethos (attempt to replace ʻand to suffer on behalf of the other without clarity for direction) (becoming the victim):

-

In overloading, the tendency is to quit: this results from the crisis of performance anxiety and professional incompetency; the pain of the depleted self and depleted performer. Healing implies treatment and medication.

-

In overexposure one wants to 'rest' and to 'retreat' (spiritual repurposing): this results from the emotional exhaustion of professional competency: the pain of the depleted helper and depleted co-sufferer. Healing implies debriefing and group sharing (to be interconnected to other caregivers in the field) as well as a reassessment of existing God-images.

-

In vicarious traumatisation one wants to revisit and reframe one's paradigmatic framework of interpretation. Healing implies a re-assessment of the appropriateness of the theory behind the caregiver's engagement in order to change meaning.

What should be made clear at this point is that resulting from the interconnectedness of the three issues at stake, compassion fatigue develops over a period of time and, as a process, can be manifested in different ways.

The hermeneutics of compassion fatigue: Seeing the bigger picture within a process of understanding

Without any doubt, compassion fatigue is a process category (Figley 2002:1-14). As a process category, compassion fatigue consists of the following:

-

A constant awareness of a very specific event or tragedy that acted as a kind of trigger factor.

-

An overexposure to suffering on a constant and continuous daily or weekly scale. Empathy is triggered by an external factor making an appeal on one's compassion.

-

The existence of an intensified empathetic ability (sensitivity) to notice the pain of the other (compassion compulsion).

-

An empathetic response: an ability to detect suffering to the extent that the helper makes an effort to diminish the suffering of the sufferer.

-

Disengagement and differentiation: this refers to the ability of the helper to distance him or herself from the continuous misery experienced by the traumatised person.

-

Sense of satisfaction: this refers to the sense of achievement the helper feels resulting from his or her efforts to help the person in need.

-

Residual compassion stress: this refers to the compulsive demand for action in order to relieve the suffering of others.

-

Prolonged exposure: this component of the process refers to the on-going sense of responsibility to care for the sufferer. Normally it takes place over an extended period of time (it describes a kind of cumulative result of internalising the helplessness of the other).

-

Traumatic memories: the trauma of unexpected tragedy and irreparable loss triggers guilt and shame. It even underlines the failure to cope or to help in an efficient way.

-

Other life demands: there are many other issues making an appeal on one's compassion. Unexpected changes that occur in schedules, routines and managing life responsibilities, that demand our attention, bring about an intensified awareness of capacity and ability.

-

Vicarious traumatisation: the transfer of the predicament of the sufferer's pain infiltrates the caregiver's framework of reference to such an extent that the healer's convictions become disrupted and confused. This results from the fact that the suffering or pain of the other makes an appeal on one's suffering-with and on behalf of the other. Internally doubt and a kind of inner nausea and resistance against the nonsense of suffering in general develops. The internal conceptual and cognitive framework is exposed as being inappropriate in terms of the sustainability of the caregiver's compassion.

The following diagnostic diagram gives a depiction of compassion fatigue as a cumulative process. The wear and tear of compassion in caregiving does not develop instantly and suddenly. It develops often over several years and as a result of constant and continuous exposure to suffering (Figure 2).

Compassion satisfaction

Compassion fatigue should be understood in close connection to the indicators for efficiency in caregiving. To act according to the expectations of one's caregiving profession, and in the light of the character of one's pastoral identity, as well as a clear theoretical framework for the field and discipline of pastoral care, leads to experiences of 'satisfaction' (an awareness of appropriateness and competency). Coherence between theory and praxis enhances compassion satisfaction. Congruency between the caregiver and his or her pastoral commitments also add to experiences of compassion satisfaction.

Satisfaction is determined by the following:

-

Efficacy: How efficient is my input?

-

Beneficiary: How beneficial is the helping relationship? Did the person benefit?

-

Healing: Did the helping relationship instigate change? Did it make any difference (result)?

-

Experience of fulfilment: Do I have a feeling of being content with my work (success).

-

Constructive feedback: The experience of being competent and acknowledged by peers in the field.

Satisfaction in pastoral ministry should be assessed in close connection to a sense of vocation and calling. The burning question is then: To what extent is the caregiver motivated by a personal calling of God to a ministry of compassion? Is my passion merely based on emotions or directed by a clear image of God and the interplay between divine presence and a theology of compassion?

Coping with the reality of compassion fatigue

The fact is that caregivers should acknowledge that compassion fatigue is a 'normal reaction' to the suffering of the other in the attempt to help and is not necessarily 'abnormal' in the sense of sever pathology. The process of understanding the differentiation between burnout, compassion fatigue and vicarious traumatisation, is part of 'managing' the phenomenon.

The following coping steps should be taken into consideration:

-

Acknowledge the phenomenon and differentiate between the other features of spiritual stress.

-

Compare the negative cost of caregiving against the background of possible positive gain and possible credits: the dynamics of loss and gain.

-

Exercising unconditional love: this is the opportunity to care without expectation of any form of compensation; this is the dynamics of love and sacrifice. Sacrifice without an understanding of the ethos of unconditional love and mercy, becomes the unbearable trauma of vicarious suffering.

-

Contribution to well-being and healing within the realm of human suffering: This is the dynamics of quality (mode) and quantity (numbers); ability and limitation.

-

Invest in human dignity irrespective of possible outcome and results: to care and to help are to dignify humans; this involves the dynamics of life and death.

-

The perception of pastoral caregiving as an opportunity to integrate theory with practice; this is the dynamics of skills and integrity.

-

Exposure to suffering should be used as an opportunity to enrich one's life; achieve a sense of life-fulfilment; the dynamics of vocation (commitment) and profession (career or job and duty).

The spiritual healing of the wounded healer: Prevention is better than cure

The remark has been made that instead of attempting to merely quit, there is the need in compassion fatigue to find a quiet place for reflection and debriefing. Both the outer space of a retreat, as well as the inner space of an internal reflection on the meaning of compassion, is necessary. In order to heal the wounded healer, caregivers should keep in mind the two levels of compassion:

1 Compassion as an affective category (exponent of the affective dimension in our being human; a deep sympathy and sorrow for another who is stricken by suffering or misfortune, accompanied by a strong desire to alleviate the pain or remove its cause) (Figley 2002:2; Stamm 2002:107-119).

2 Compassion as a spiritual category connected to a God-image. In this regard, the notion of a compassionate and suffering God (Louw 2000) in theopaschitic theology can play a decisive role in the treatment of spiritual exhaustion. In the processes of repurposing and reframing attention this should be given the role of a divine compassion in caring (ta splanchna, oiktirmos).

One should acknowledge that compassion refers to both empathy (feeling with) and sympathy (being-with). Compassion, resulting from empathy, is the attempt on an affective level to probe into the framework of reference of the other. However, feelings can be very misleading and unstable. In sympathy, there is indeed a correspondence of feeling (the same) resulting from transfer on an emotional level and identification on a being level. In sympathy, there is the attempt to identify oneself with the emotional condition of the other.

The unique feature of caregiving resides in two basic pastoral entities, namely comfort and compassion. Unique to the spirituality of pastoral care, within the Christian tradition of cura animarum, is the fact that the pastoral ministry deals with comfort and consolation not merely as affective, cognitive or conative categories. Comfort is deeply and primarily a spiritual category linked to the theological dimension of the Christian faith. Comfort and care emerge as a result of the comfort of God. Pastoral comfort is in essence an exemplification and embodiment of the passion and suffering of Christ. Resulting from the interrelatedness between comfort and compassion, the passion in compassion entails more than feeling. It should be viewed as an existential category (being-with) within the theological framework of a theologia crucis (The cross of Christ as an enfleshment of divine suffering and compassion) (Gerhardson 1981).

Despite the dominant role of the affective in compassion I want to argue that, from the perspective of spirituality, compassion entails more. My presupposition is that compassion:

1 Implies habitus; it describes a mode of being-with the other in order to instil human dignity and meaning within the realm of suffering and death.

2 Refers to the sensitivity for the unique identity of the other in order to bridge the gap or barrier between the helper and the helplessness of the other. At stake is the notion of human suffering and the framework (the meaning of suffering) from which we interpret the other.

3 Implies an intimate space of unconditional love in order to penetrate the possible personal isolation, rejection, stigmatisation and discrimination of the patient or person.

4 Aims to replace the discomfort of the other with a comfort that will be beneficial to the other and contribute to well-being and healing in a spiritually sustainable way. Compassion wants to instil a mode of hope and appropriate future orientation (compassion as anticipation).

5 Includes the ability to make a true discernment about what really counts in life. In this regard, compassion is related to the tradition of wisdom. In wisdom thinking, one probes into the dynamics of right and wrong, appropriate and inappropriate. Compassion is not exercised without a moral awareness.

6 Represents, as a relational category, sources of comfort that can enhance the quality of life.

As a result of the importance of an interdisciplinary approach, a close connection between pastoral caregiving and healing models in psychological counselling exists. However, within a team approach in the healing and helping professions, differentiation is important. As said, pastoral caregiving should essentially be linked to the comfort of God.

We as pastoral caregivers are, by the fruit of the Holy Spirit, equipped to bestow compassion and, therefore, to empower suffering human beings. From the presence of the Holy Spirit emanates what Paul called: parrhēsia (1 Th 2:2); a kind of spiritual strength and boldness that motivates one to proceed with life and one's vocation as a Christian, despite hardships and trials (spiritual fortology and resilience).

The emphasis on strength is intended to encourage a move away from the paradigm of pathogenic thinking and to link health to a sense of coherence, personality hardness, inner potency, stamina or learned resourcefulness (Strümpfer 1995:81-89; 2006:83).

What should be reckoned with in a spiritual approach to the healing of the wounded healer is that comfort as compassion is, in Christian spirituality, essentially a theological category. Comfort displays the mercy (hēsēd) of a living God within a covenantal encounter with human beings. In the New Testament the mercy of God is often described in bowel categories, namely ta splanchna (splanchnizomai: movement and pain within the bowels)11. A good example of comfort as linked to a theology of the intestines is Luke 15:20. When the father saw his prodigal son, he was moved with pity and tenderness. Ta splanchna displays the unconditional love and mercy of a caring father; it is essentially a component of the father's being functions.

Compassion in pastoral caregiving is about the display of ta splanchna: one is moved by the predicament and suffering of the other within a spiritual awareness of the ta splanchna of God (the theological motive in compassion). Compassion then becomes the normal obligation and responsibility of a caregiver; it is part of our spiritual habitus, attitude and aptitude. Compassion in this regard is about our Christian calling (professional vocation) and not about our occupation (professional job).

However, in caregiving one is often overwhelmed by the pain and suffering of human beings. In the light of so much undeserved suffering, hopelessness and helplessness, a kind of spiritual exhaustion, sets in.

How then should one understand spiritual exhaustion in caregiving? It is indeed true that the caregiver as healer often becomes wounded. The wounded healer needs healing too. Thus, the argument exists for a theological paradigm switch: from the 'fit' (omnipotent/pantokrator) God, to the bowel categories of a compassionate God.

In order to invest in a process of continuous healing, the following needs should be addressed. One needs:

-

An appropriate support system: a safe space to ventilate.

-

Professional feedback and scientific discussion: mutual evaluation with peer researchers in your field (informal talk therapy).

-

Regular debriefing12: backward-reflection within a team approach.

-

Group counselling (on a weekly basis): to provide a structure for mutual pastoral caregiving.

-

Solitude: a place and space to ponder and to philosophy on the meaning and purposefulness of life (spiritual retreat/retraite).

-

Always to move from competition to compassion; to deal with the root issue, namely compassion.

-

To rediscover the spiritual realm of the helping profession: to see compassion as a spiritual entity (being function), not merely as emotional investment.

-

To scrutinise and assess appropriateness of belief systems, God-images and basic convictions: this is the motivation factor (why and for what purpose?).

-

To be generous to yourself and create a kit-cat-brake: do something else (different) which you will enjoy; vocation; recreation (spoil yourself within me-time).

-

To revisit existing paradigms (patterns of thinking embedding philosophies of life) in order to create an accommodative stance in life: what you can change you change by setting new goals; what you cannot change you need to accept (live the problem).

-

To undergo a paradigm shift: move from Mr or Mrs Fixit to Mr or Mrs Support-them (helping is to be there with …). Be available and do not try to fix everything; move from doing functions into being functions.

-

To maintain resilience: a non-anxious presence; gracious patience and courage; concentrating on being-functions.

-

To develop a sense of humour combined with continuous reframing.

The ability to see a positive side in a traumatic situation, with all its unavoidable negative aspects, is related to a sense of humour. Moran (2002:139-153) refers to humour as a coping strategy in the emergency context. A sense of humour can be seen as a personality predisposition, which might be measured as a propensity to laugh at certain things, including oneself. To a certain extent, humour entails more than laughter. It is actually the ability to see events from a different perspective and to understand the relativity of life events. It is about reinterpretation. Reinterpretation occurs because humour provides a link between two normally un-associated items or contexts: 'humour permits things to be seen in a new light because it allows the unexpected association of two normally unrelated or even conflicting scenarios' (Moran 2002:141). This unexpected association is referred to as incongruity and the 'bi-sociation of ideas'.

Humour is related to cognitive reframing. D. Capps (1990:10) calls reframing the ability to change the frame in which a person perceives events in order to change the meaning. When the meaning changes, the person's responses and behaviour also change. To change a meaning implies changing the conceptual or emotional setting of a viewpoint in relation to which a situation is experienced and to place it in another frame, which fits the 'facts' of the same concrete situation equally well or even better, and thereby changes its entire meaning (Capps 1990:17).

Conclusion

Compassion fatigue is actually a yearning for wholeness resulting from a temporary failure within the realm of a long-term vision and caring strategy. One can say that compassion fatigue develops as a by-product of the failure to 'see' the 'bigger picture'. One becomes so overwhelmed by the anxiety for the loss of significance that one goes temporarily on a spiritual strike. One knows that technical counselling skills or managerial skills will fail to cope with the demands of human suffering in a sustainable way.

Compassion fatigue:

-

Is accumulative: it is the impact of repetition and exposure.

-

Challenges the roots and character of a professional helper.

-

Exposes the so-called 'skilled helper' to the existential reality of spiritual pain and sorrow or pity within the context of human vulnerability challenged by the reality of death.

-

Creates opportunities for spiritual growth and the biding of resilience.

-

Operates within the spiritual tension of contradiction: paradox, antinomy and polarity.

-

Surfaces resulting from an overexposure to suffering and an acute awareness of human failure in the face of unpredictable tragedy and on the threshold of liminality.

With reference to the unique character of pastoral caregiving, a theological understanding of suffering can help one to accept the limitation of our involvement and to differentiate between compassion capacity and compassion limitation. In this regard the theopaschitic notion of a suffering God (Fretheim 1984) can be most helpful to gain perspective on the character of God's involvement in suffering. In terms of a theological understanding of compassion, compassion refers to God's mercy as expressed in the bowel categories of ta splanchna: the divine compassion fatigue of a suffering God. The forsakenness of Christ on the cross (derelictio) depicts the helplessness of God. God becomes a Co-Partner in the struggle to cope with the victimisation of human helplessness and vulnerability.

The essence, therefore, in a functional approach to caregiving is a spiritual facticity: caregivers represent the compassion of God, embody the presence of God and enflesh the spiritual realm of hope. Caregivers are beacons of hope within the blurred and dark vistas of life. The challenging question is: How is this core paracletic function represented in a more general understanding of the different functions of pastoral caregiving?

The further assumption is that a reframing of the functions of caregiving, combined with a clear insight regarding the driving forces and paradigmatic, theological framework behind compassion, can contribute to a more appropriate and healthy approach to the inevitable phenomenon of compassion fatigue in the pastoral ministry.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationships which may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

References

Bonhoeffer, D., 1959, The cost of discipleship, SCM Press, London. [ Links ]

Bonhoeffer, D., 1998, Widerstand und Ergebung, Chr. Kaiser Verlag, Gütersloh. [ Links ]

Campbell, C.L. & Cilliers, J.H., 2012, Preaching fools. The Gospel as rhetoric of folly, Baylor University Press, Waco, TX. [ Links ]

Capps, D., 1990, Reframing. A new method in pastoral care, Fortress Press, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Capps, D., 1993, The depleted self. Sin in a narcissistic age, Fortress Press, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Esser, H-H., 1976, 'Splanchna', in C. Brown (ed.), Dictionary of New Testament theology, vol. 2, pp. 598-601, Paternoster Press, Exeter. [ Links ]

Figley, C.R., 1955, Compassion fatigue. Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized, Brunner/Mazel, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Figley, C.R., 2002, 'Introduction', in C.R. Figley (ed.), Treating compassion fatigue, Brunner-Routledge, New York, NY/London. [ Links ]

Fretheim, T.E., 1984, The suffering of God, Fortress Press, Philadelphia, PA. [ Links ]

Gentry, J.E., 2002, 'ARP: The Accelerated Recovery Program (ARP) for compassion fatigue', in C.R. Figley (ed.), Treating compassion fatigue, Brunner-Routledge, pp. 123-137, New York, NY/London. [ Links ]

Gerhardson, B., 1981, The ethos of the Bible, Fortress Press, Philadelphia, PA. [ Links ]

Hart, A.D., 1984, Coping with depression in the ministry and other helping professions, Word Books, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Heidegger, M., 1963, Sein und Zeit. Max Niemeyer Verlag, Tübingen. [ Links ]

Hernandez, W., 2012, Henri Nouwen and spiritual polarities: A life of tension, Paulist Press, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Louw, D.J., 2000, Meaning in suffering. A theological reflection on the cross and the resurrection for pastoral care and counselling, Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main. [ Links ]

McCann, L. & Pearlman, A., 1990, 'Vicarious Traumatization: A framework for understanding the psychological effects of working with victims', Journal of Traumatic Stress 3(1), 131-149. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00975140 [ Links ]

Moran, C.C., 2002, 'Humor as moderator of compassion fatigue', in R. Figley (ed.), Treating compassion fatigue, pp. 139-153, Brunner-Routledge, New York, NY/London. [ Links ]

Neuman, D.A. & Gamble, S.J., 1995, 'Issues in the professional development of psychotherapists: Countertransference and vicarious traumatization in the new trauma therapist', Psychotherapy 32(2), 341-347. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.32.2.341 [ Links ]

Pfifferling, J.H., 2003, 'Overcoming compassion fatigue', Family Practice Management 7(4), 39-48. [ Links ]

Simon, C.P., 2011, 'Resilienz. Die innere Stärke wecken', Geowissen 48, 160. [ Links ]

Stamm, H., 2002, 'Measuring compassion satisfaction as well as fatigue: Developmental history of the compassion satisfaction and fatigue test', in R. Figley (ed.), Treating compassion fatigue, Brunner-Routledge, New York, NY/London. [ Links ]

Strümpfer, D.J.W., 1995, 'The origins of health and strength: From "salutogenesis" to "fortigenesis"', South African Journal of Psychology 25(2), 81-89. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/008124639502500203 [ Links ]

Strümpfer, D.J.W., 2006, 'The strengths perspective: Fortigenesis in adult life', Journal for Social Indicators Research 77(1), 11-36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11205-005-5551-2 [ Links ]

Valent, P., 2002, 'Diagnosis and treatment of helper stresses, traumas, and illnesses', in C.R. Figley (ed.), Treating compassion fatigue, pp. 17-37, Brunner-Routledge, New York, NY/London. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Daniël Louw

171 Dorp Street, Stellenbosch 7600

South Africa

djl@maties.sun.ac.za

Received: 08 May 2015

Accepted: 27 July 2015

Published: 13 Oct. 2015

Prof. Daniël Louw is Emeritus Professor in the Department of Practical Theology, at the Faculty of Theology, Stellenbosch University, South Africa. This article is published in the section Practical Theology of the Society for Practical Theology in South Africa.

1 Compassion fatigue is a more user-friendly term for secondary traumatic stress disorder. It is related to the cognitive schema of the therapist or caregiver (social and interpersonal perceptions of the morale) (see Figley 2002:1-14).

2 For a detailed outline of compassion fatigue burnout symptoms, see Figley (2002:7).

3 According to J.E. Gentry, compassion fatigue is the convergence of primary traumatic stress, secondary traumatic stress and cumulative stress or burnout in the lives of helping professionals and other care providers. Burnout is a state of physical, emotional, and mental exhaustion caused by a depletion of ability to cope with one's everyday environment (Gentry 2002:123-137).

4 It is clear that compassion fatigue can be classified as a helper dysfunction (Valent 2002:17-37).

5 Capps relates depletion to self-failure. It is related to self-pathology and self-fragmentation within our narcissistic age, with its emphasis on productivity and achievement (Capps 1993:97-98).

6 See in this regard the work of A.D. Hart (1984), Coping with depression in the ministry and other helping professions. In his research, Hart focused predominantly on the factor of work stress, its connection to burnout, resulting in depression. At that time, the notion of compassion fatigue was quite new and not taken into consideration in the assessment of spiritual stress within the framework of ministry.

7 'Der Tod im weitesten Sinne ist ein Phänomen des Lebens. Leben muss verstanden werden als eine Seinsart, zu der ein In-der-Welt-sein gehört.' Sein und Zeit. (Heidegger 1963:246).

8 For a discussion on theodicy (the philosophical attempt to justify God within an acute awareness of evil and suffering, the positivistic attempt to 'prove the goodness' and love of God), see Louw (2000), Meaning in suffering: A theological reflection on the cross and the resurrection for pastoral care and counselling.

9 See in this regard: D. Bonhoeffer, The cost of discipleship (1959). Important for our discussion is Bonhoeffer's contention that grace is never cheap grace. Grace is costly and is, thus, the reason why discipleship, as a spiritual venture, will always be costly. Inevitably, the side effect of ministry will imply a kind of spiritual exhaustion. In his book, Widerstand und Ergebung (Bonhoeffer 1998), this kind of spiritual exhaustion surfaces within the liminality and bipolarity of resistance and the challenge of costly grace, namely to forgive.

10 The figure is designed in order to bring clarity on what is meant by diagnosis in spiritual exhaustion. It could be used in counselling to exhausted caregivers.

11 It is my contention that the passio dei is an exposition of the praxis concept of ta splanchna. The latter is related to the Hebrew root rhm, to have compassion. It is used in close connection to the root hnn, which means to be gracious. Together with oiktirmos and hesed it expresses the being quality of God as connected to human vulnerability and suffering. The verb splanchnizomai is used to make the unbounded mercy of God visible (Esser 1976:598).

12 C.P. Simon in an article on resilience pointed out that it has not been proven that patients after debriefing would be less traumatized in future. After the tsunami-catastrophe 2004, the World Health Organization warned against therapeutic intervention that focuses on immediate intervention. To talk immediately about the trauma can even heighten the impact and effect of the trauma on a person. 'Stattdessen sollte man zunächst auf die Selbstheilungskräfte der Menschen setzen und mit Therapieangeboten abwarten, ob die Betroffenen wirklich Hilfe benötigen' (Simon 2011 160).