Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

HTS Theological Studies

versión On-line ISSN 2072-8050

versión impresa ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.71 no.2 Pretoria 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v71i2.2625

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Technologically changing African context and usage of Information Communication and Technology in churches: Towards discerning emerging identities in church practice (a case study of two Zimbabwean cities)

Vhumani Magezi

Faculty of Humanities, School of Basic Sciences, North-West University, Vaal Triangle Campus, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The last decade has seen massive progress in technological advancement in Africa. Many pastors have embraced the use of technology in their religious and ministerial practices. Within such a context, it is necessary to understand the various identities of the African pastor emerging from responses to the use of technology. This article discusses technological use in churches, particularly focusing on the changing technological context of Africa. The article uses Zimbabwe as a case study to assess and determine technology use and the responsive emerging identities of pastors. Three identities of pastors arising from increased technological use in Zimbabwe have been discerned. The first identity is that of the pastor who is on a par with the world. He is a technology embracer and is as sophisticated as the congregational members. He is a networker and entrepreneur. The second identity is that of a pastor who is trailing society and technology. He is a cautious technology embracer and is a confused technology consumer. The third identity is that of a pastor in isolation. He is a technology objector, and is unconnected, ignorant and feels that God is somewhat an enemy of technology.

Introduction and background

Castells (2000) unequivocally states that technology has revolutionised the world. It has become an essential part of people's lives. Information and Communication Technology (ICT) and technological devices and platforms have become common features of business and society. Use of Technology.com (2011), which is an organisation devoted to providing research information on the use of technology globally, made an illustrative list of over one hundred ways in which technology is used in people's lives. The uses fall into more than 36 categories, which include business and business communication and organisation, product development, teaching, the workplace, customer service, marketing, education, human resource management, health care, decision-making, the classroom, banking, agriculture, accounting, bakeries, art and churches. However, there are far more uses of technology than are listed here.

The penetration of technology into every sphere of people's lives suggests that technology has to be embraced. As far back as 1995, Kumar and Kar (1995) observed the way in which information technology (IT) had extensively penetrated the lives of people and wisely predicted that every individual in the world will be affected by it. Scholars such as Ossai-Ugbah (2011), Ukodie (2004), Brakel and Chisenga (2003), and many others rightly maintain that ICT will be the driver of development in the 21st century and beyond. They base their argument on the extent to which ICT has evolved since the mid-20th century.

A high level of technology use is not only being experienced in the West, but the use of technology in Africa has arisen to an equal extent. There has been an explosive growth of technology use in Africa, particularly in the area of mobile phones. A study by the World Bank and the African Development Bank (2012) revealed that in 2000 there were fewer than 20 million fixed-line phones across Africa. The number of fixed-line phones has been growing slowly, with only the elite and the wealthy having access to them. However, with the advent of mobile phones the situation has changed radically. By 2012 there were more than 500 million mobile phone subscribers in Africa, which was more than in the US or the European Union. This makes Africa the region which has the fastest-growing use of mobile phones in the world. For instance, the World Bank and the African Development Bank (2012) noted that in some African countries more people have access to mobile phones than to clean water, a bank account or even electricity.

Kitetu (2008) and Isaacs (2007) agree that technology is now used in Africa to a huge extent. The World Bank and the African Development Bank (2012) commented that Africa's economic growth in the last decade has been driven by mobile phones. They added that foreign direct investment (FDI) is booming and Africa is now a much easier place to do business because of the greatly improved connectivity. The World Bank and the African Development Bank (2012) added that ICTs contribute around 7% of Africa's gross domestic product (GPD), which is higher than the global average. This is because in Africa mobile phones give access to some services available in traditional forms in more developed countries, such as financial credit, newspapers, games and entertainment. The evidence provided by the World Bank and the African Development Bank (2012) indicates that Africa, which was once an ICT laggard, is now becoming an ICT leader. Examples of African ICT innovations include dual SIM card mobile phones and the use of mobile phones for making payments and transferring money, which has spread across the continent and beyond.

Notwithstanding the significant progress in technology use in Africa, Kitetu (2008) in Gender, science, and technology: Perspectives from Africa, paints a dark picture regarding women's access to technology. She argues that women and girls lag behind men in technology access and use, and adds that femininity and general domestic confinement weakens women's participation in technology use. Mohapi (2014), in Technology in Africa, is disillusioned by the limited access of poor and rural people to some technological platforms. He cites low Internet access as an example. The World Bank and the African Development Bank (2012) are therefore right that the deployment of ICTs and the development of applications must be rooted in the realities of local circumstances and diversity.

Limited access to and use of technology in Africa have been noted in a number of research projects. Country studies for Kenya and South Africa conducted by InfoDev managed by the World Bank (2012) revealed that in South Africa, three-quarters of the population have phones, but the use of data applications is fairly low. The one exception is the social networking platform MXit. There is also a growing use of other social media, notably Facebook. However, other applications such as mobile money, which are widely used in other parts of the continent, do not seem to be well targeted at the poor. In the case of Kenya, the study revealed that the top three activities conducted with mobile phones were calling, text messaging and sending or receiving mobile money. In Kenya, 25.3% of mobile phone owners stated that they browsed the Internet using a mobile device. The findings from the InfoDev study point to the need for people to own smartphones to access the Internet via phones. This would mean increased costs for mobile phones which would prevent the poor from owning them.

A detailed analysis of the African situation regarding the use of technology, particularly mobile phones, the Internet and broadband, is presented in a report of a study conducted by Research ICT of the University of Cape Town, South Africa, authored by Gillwald (2012). Although the study does not cover all the countries on the continent, its findings are revealing and give a fair picture of the diversity of technology use across the continent. The percentage of mobile phone owners who use the prepaid system is as follows: South Africa 87.3%, Namibia 91.8%, Ghana 97.4 %, Tanzania 99.5%, Cameroon 99.1%, Rwanda 90.1% and Ethiopia 98.4 %.

Further analysis of data by Research ICT of the University of Cape Town revealed that Tanzania has the highest number of people who cannot afford the cost of mobile phones, and whereas Ethiopians can afford them, there is limited connectivity. South Africa has the highest number of people with mobile phones and Ethiopia has the lowest. With the exception of Ethiopia, where mobile phones are mostly used for sending emails, people in all the other countries surveyed mostly use their phones for browsing the Internet, with South Africa recording the highest number. South Africa has the highest number of people who have personal computers, with Tanzania having the lowest. Thus for the countries surveyed, South Africans are generally shown to have more access to mobile phones, the Internet and computers. The telling finding, however, is the high level of Internet browsing using mobile phones. As Internet browsing requires a smartphone, the situation suggests that people in Africa probably need to upgrade their phones, which in many instances cannot be afforded by the rural poor. This is also a limitation among people with low literacy.

Kabweza (2012), reporting on data from the Postal and Telecommunications Regulatory Authority of Zimbabwe (POTRAZ), noted that Zimbabwe's teledensity increased from 81.5% in the first quarter of 2012 to 89.9% in the second quarter of 2012. This increase indicated a rapid adoption of mobile phones by Zimbabweans in 2012. Considering that in June 2011 Zimbabwe's teledensity was 56.6%, the increase is remarkable. Currently Zimbabwe has a teledensity of 90% and mobile penetration of 87%. This data, as well as data from the InfoDev study, reveal that indeed in the past five years, Africa's mobile phone market has rapidly expanded. Mandoga, Matswetu and Mhishi (2013) in their study revealed that the use of technology in rural Zimbabwe, particularly in schools, is very low. Dube (2010), in her Master's dissertation focusing on women and ICT, observed that there is a gap between what is promised to women and the actual ICT services in Zimbabwe. While Biztechafrica (2014) claims that Econet, the leading mobile operator in Zimbabwe, has a penetration of more than 100%, the picture painted by the Zimbabwe National Gender Policy (2013-2017) is not very positive, particularly of women and rural areas. The policy document notes that 70% of the female population resides in rural areas, and yet Internet access is a mere 0.07%. This shows a very low level of Internet access among rural people.

The use of technology and access to technology as a proxy for use in Africa indicate that there has been significant progress. Many people are using technology. In Zimbabwe, as in other African countries, technology use is significantly much higher in urban areas than in rural areas. With the majority of rural people being women, the consequent effect is also low technology use among women. With technology infused into every area of people's lives and society, how are churches in Africa using technology? What identities of pastors are emerging due to the increased use of technology? Ossai-Ugbah (2011) is of the opinion that since churches are part of the information community, it is necessary to investigate how information communication technologies are used in a church. Importantly also, a church is a sub-system of society (Magezi 2007). In response to the above questions, I shall focus on a Zimbabwean case study to determine the extent of technology use and the emerging identities of pastors in African churches.

Research methodology

The research design for the empirical study is an interpretive paradigm. In an interpretive paradigm, the researcher describes as well as interprets phenomena in order to derive meaning from the situation. Marshall and Rossman (2006), Maxwell (2005), and Babbie and Mouton (2006) explain the interpretive paradigm as being grounded in a constructivist philosophical position whereby complexities of the sociocultural world are experienced, interpreted and understood in a particular context. A social situation is examined by the researcher entering the world of others and attempting to achieve a holistic rather than a reductionist understanding of the subject matter. The emphasis of an interpretive paradigm is on discovery and description, and the objectives are generally focused on extracting and interpreting the meaning of experience. This is different from quantitative research, where the intent is usually to test hypotheses to establish facts and to designate and distinguish relationships between variables.

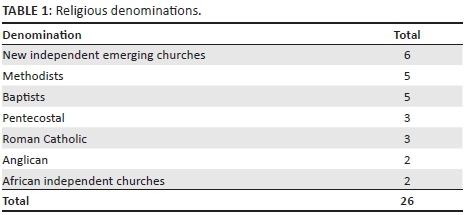

The data was collected using a semi-structured questionnaire with four questions focusing on the use of technology in the church. The questions elicited information on the extent of technology use, factors influencing use, opportunities resulting from the use of technology, and weaknesses of technology use. A purposive sample of 26 pastors in two cities (Mutare and Harare) were interviewed. The interviews were conducted by the present researcher. The pastors were drawn from the religious denominations seen in Table 1.

The majority of the pastors (74%) were at least 11 years in the ministry, followed by 3-5 years (15%), then 6-10 years (7%), and lastly 0-2 years (4%). The responses were transcribed, coded and analysed using a grounded theory approach whereby codes emerge from the data set as read by the researcher (Babbie & Mouton 2006). The codes, i.e. 'themes' are then presented in thematic maps followed by summarised descriptions. Verbatim quotes of the respondents are cited to illustrate responses in each category code.

Presentation of results

The transcribed interviews were organised into themes. Sections of text units such as words, phrases and paragraphs that best addressed the topic of technology use in the church were extracted. The themes that emerged from the interviews are indicated on the thematic map below (Figure 1). The pastors' responses reflected three main positions regarding the use of technology. These positions are linked to the perceived emerging identities indicated on the map as subthemes.

The pastor as aggressive embracer of technology

A number of pastors reported that considering the extent of technological advancement and consequent use in people's lives, one has to embrace technology aggressively. The following responses indicate aggressive embracing of technology:

'There is no going back on technology. It's the order for the day everywhere, including the church. We have embraced technology in our worship and various ministries.' (Respondent 3)

'We are using technology big time although others in the church are a bit sceptical, for instance in the use of Twitter during sermons.' (Respondent 7)

The technology explorer

The pastors who embraced technology aggressively expressed their willingness and initiatives to revolutionise the church and the church ministry by exploring new ways via technology.

'You have to understand that you cannot stand and only sing old hymns from a hymn book. You need to attract young people by exploring new ways of using technology to make church enjoyable.' (Respondent 15)

'You have to keep discovering new ways of using new technologies. I use my tablet to preach and I can quickly show pictures on the projector. It's sometimes disruptive but some people like it. It's trying to do new things using technology.' (Respondent 19)

The harvester of technology benefits

Some pastors linked their use of technology to the benefits that result from it. They view using technology in Christian ministry as harvesting. The harvest results from the benefits of technology:

'Technology saves me time and money. I used to worry about printing my sermons but now it's no longer the case. I can edit my sermon depending on the mood and vibe of the church. I am harvesting the benefits of technology.' (Respondent 9)

'We are computerising most of our ministries. Our membership records are a click away. We are benefiting from technology advancement. Administratively and ministry-wise we are integrating technology.' (Respondent 11)

Lukewarm technology embracer and user

There is a group of pastors whose responses are on the borderline regarding the use of technology in the church. On the one hand they seem to realise its benefits, and yet it seems wrong for their denomination. They are embracing technology, but they are lukewarm about its use in the church:

'I am a bit divided about using all sorts of technological gadgets in the church. Some churches are using it but for me it has to be slowly. We are using simple things like projecting your sermon outline but not to the extent of putting your sermons on YouTube or tweeting in the church.' (Respondent 15)

'I use technology to invite people to meetings and other communications, but not at the centre of worship service. I preach from my manuscript. I feel people should listen to the word attentively without obstructions.' (Respondent 24)

The technology-cautious embracer

Some pastors expressed the need for caution in using technology in the church:

'As a church you don't have to jump to embrace everything offered by the world. I am very cautious in my use of secular information and knowledge. This goes for technological equipment.' (Respondent 16)

'In our church we assess every new trend and debate as leaders. We are careful about uncritically embracing foreign practices in the church. The church is sacred. However, for home visits, arrangement for meetings and invitations we use technology such as Whatsapp.' (Respondent 17)

The technology user in denomination chains - constrained by denomination tradition

A significant number of young pastors in traditional missionary1-started churches reported being caught in a tension between denomination and technology use:

'We use technology such as phones like other people, but we don't do much beyond that. I feel we need to use new technology, for instance posting church information on Facebook but the response has been very low. Sometimes other senior pastors are also sceptical about such initiatives.' (Respondent 1)

'My church has a long way to go regarding using technology gadgets in services. We sing hymns and use no projectors at all. With the youth we try to be innovative but the environment is stifling.' (Respondent 5)

Objectors to use of technology in the church

There were pastors from some denominations who viewed technology as equipment that did not glorify God. They argued that the consumerism and self-glorification of celebrities and televangelists is in contrast to the humility expected of Christians. These pastors objected to the use of technology in the church even though they owned mobile phones and computers:

'The coming of technology and globalisation is a desire to propagate a culture of the Devil. How can we associate initiatives that have roots in humanism with God? We believe people can use technology outside but not in the church.' (Respondent 26)

'In our church we don't have buildings so how can we use projectors or any other equipment? We discourage our members from taking things that are foreign to the church.' (Respondent 22)

Technology as the enemy of the Bible

'I strongly feel technology at its core is an enemy of what the Bible teaches such as meditation.' (Respondent 26)

Distinction between sacred and secular: 'Christian and secular'

'The church and the Bible are sacred. In our church therefore we believe and practice that what is sacred should not mix with what is secular, e.g. technological equipment.' (Respondent 22)

Interpretation of results -determining technology use in the church and emerging identities

A number of approaches could be employed as analytical lenses of the above responses. For this discussion the focus will be on the extent of technology use in the church and the emerging identities of the pastors. In interpreting technology use, technology access will be considered a proxy of use. Fearon (1999) describes identity as either a social category, defined by membership rules and alleged characteristic attributes, or expected behaviours. It also refers to socially distinguishing features that a person takes special pride in or views as unchangeable but socially consequential. The identities of the pastors will be inferred from their testimonies as well as their view on the position of technology in the life of their church.

Technology-aggressive embracer

The pastors who are technology embracers are technology explorers and they focus on the benefits of technology. They are generally young, technologically savvy and viewed as sophisticated. These pastors have fully embraced technology in their ministries. They explore various ways in which their ministries could be enhanced by it. They are aware of the benefits of technology and they use it in the church without restriction. The reasons cited for widely using technology are the 'need to connect with broad membership' as well as a 'desire to attract and be relevant to young Christians'. The majority of these churches are independent and self-founded by the respective pastors. The major uses of technology include preaching from tablets, blogging, websites and connecting on social networks such as Twitter, Facebook and Whatsapp with church members. Examples of these churches are Kingdom Church (member of the New Frontiers), One Church, Greystone Park Fellowship and Celebration Centre, just to mention a few.

The pastors of the churches such as the ones cited above, which use technology to a great extent, project an image of sophistication to their members. These pastors are sometimes way ahead of their peers in other churches regarding technology use. The pastors are considerable social networkers who spend a significant amount of time on the Internet branding themselves. One pastor remarked, 'These young pastors are below forty years and are experimenting with how to lure people with technology'. Their main limitation, however, is resources as they sometimes have low membership. Some of these pastors are referred to as 'entrepreneurial pastors' due to their overt soliciting of financial resources from followers. Such churches are cynically called 'church businesses'. These churches and their pastors are criticised for creating an unhealthy convergence of the world and the church. One of the respondents, a young technologically savvy pastor, stated that they believe 'there is no sacred and secular as some mainline2 churches claim. This divide is unbiblical'. The majority of these young pastors are ahead of their members in the use of technology. One young pastor stated that 'church people are not as exposed as they are hence they are slow to embrace technology use in the church'. The respondents' statements revealed the ambivalence towards technology use in Zimbabwean churches. The tension between pastor and parishioners expressed by the pastor who embraced technology resonates with Filteau's (2010) observation. Filteau (2010) noted that technology may not be only costly in money, time and energy, but it also ignites conflict in many churches, and yet churches are motivated to use it, not for its entertainment value, but for its strategic effectiveness.

The scepticism shown by some members of the church towards embracing technology in the church indicates that some church members are uneasy about it. Kalu (2008) noted that while every idea or concept should be mediated and communicated through a familiar culture, which justifies the use of technology in the churches, there is a thin line between secular and Christian techniques in the use of technology. He asks how new technologies can fit into African church contexts. Kalu (2008) further asks how technology, which is characterised by merchandising, competing with one another, cost-intensiveness and legitimising popular culture can be incorporated into the Christian message. He therefore advises that our use of technology should be guarded to avoid weakening messages to fit popular appeal on YouTube as well as to avoid singling out people to make them appear more important than others and thereby breed a personality cult.

On the other hand, overuse of technology could create an island of certain churches and pastors. Gillwald, Milek and Stork (2010) reported that access to ICT in Africa is high in urban areas, leaving rural areas largely untouched. The Zimbabwe National Gender Policy (2013-2017) confirms this situation. The policy notes that Internet access is only 0.07% in rural areas. Secondly, with the majority of marginalised people in rural areas being women, (Chu Ilo, Ogbonnaya & Ojacor 2012), overemphasis on the use of technology suggests that such churches may concentrate in urban areas at the neglect of rural areas, hence weakening the missionary role of the church. Thus, notwithstanding the reported benefits of technology in some churches, there are obvious concerns. Louw (1998) advised that the pastor as shepherd needs to demonstrate sensitivity and share in the concerns and state of the sheep. As the pastor runs ahead, the sheep may be lost in the wilderness of the cares of this world; and yet it is for this purpose that the pastor is called.

The lukewarm embracer of technology and technology objectors

The second category of churches and pastors are those that are slowly and cautiously embracing technology. A significant majority of these pastors are part of congregations that belong to denomination families that are centrally controlled. In such congregational families, individual congregations have limited control. When a pastor within a particular congregation wants to use certain technologies he first has to seek approval from head office (central leadership). The churches and pastors have limited freedom to shape and design ministry at local congregation level. However, the pastor has some degree of autonomy in shaping the use of technology within set parameters. These pastors and churches use technology in a limited way, for example public address (PA) systems, data projectors and basic messaging platforms. Such pastors are caught between wanting to fully utilise technology and denomination control. These churches and pastors desire to attract the younger generation of Christians, but they are limited by denominational rigidity. One respondent described this situation as static regarding technology use. There is a desire to advance technologically but this desire is quelled by leadership. Thus despite some level of awareness of the benefits of using technology, use remains very low. Examples of such churches in Zimbabwe are the mainline churches such as Methodists, the Salvation Army and Baptists. These churches are usually controlled nationally by central leadership.

The third category is those churches that do not use technology in their worship services. ICT is viewed as a secular tool with little or no place in formal worship. These churches and pastors are hierarchical with centralised decision-making. While members of these churches use technology in other areas of life, they do not use it in the church. There is very little appreciation of the contribution of technology in the church's public worship. Examples of such churches are Roman Catholic, Anglican, End Time Message Church and Bible Believers. The worship services of these churches are statically drawn from prayer books. Church is viewed as a sacred place that is not influenced by the world. There is very limited use of technology in church during worship services.

Jones and Ough (2010) maintain that despite reservations regarding technology use, technology helps one to reach more people in and outside the church. Castells (2012), in Networks of outrage and hope: Social movements in the Internet age, proposes that there is a need to identify paths of social change in our time, rather than adhering to old ways. It would be unwise for pastors or any other church leader to resist the use of technology. Ossai-Ugbah (2011) maintains that the advent of computers and other complementary technologies has increased ministry effectiveness. Technologies such as the Internet have led congregations using computer technology to enhance and strengthen traditional ministries such as worship, fellowship, pastoral care, education, mission and community outreach, evangelism and communications. Vieira (2012), citing Pope Paul VI, refers to information technology and communications (ITC) as a modern and effective version of the pulpit through which the church succeeds in speaking to the multitudes. Vieira (2012) adds that Pope John Paul II commented that the first Areopagus of the modern age is the world of communications, while Pope Benedict XVI included the world of ITC among the major areas of apostolate for the church in Africa. Thus Pope Benedict described the world of communications as a significant force for the development of Africa and an instrument for evangelisation.

Technology is notably being used in various ways in churches and the pastoral ministry. For instance, technology is providing opportunities for the new generation of pastors to reach out to many followers through satellites. Virtual churches have been arising through the exploitation of technology (ZBC News 2012). The Internet is being used to deliver church sermons as people are becoming increasingly busy and getting so much more attached to their careers. Use of Technology.com (2011) explains a number of technology uses in the church. These include Internet sermons, social networks being used to preach the gospel, and text messages used as reminders of the gospel. And when some Christians experience challenges in their lives they may not have time to go and seek spiritual advice from church leaders, hence they are reached through text messaging. Biblical and self-empowerment messages are sent using text messaging services to assist Christians to stay on track. The study by the Barna Group (2008) on the presence of eight technologies and applications in Protestant churches in the United States of America (USA) showed a marked increase in seven areas except one, satellite dishes. The seven technologies are large screens used for showing video imagery, sending email blasts to all or parts of the congregation, operating a church website, offering a blog site or pages for interaction with church leaders, maintaining a webpage on behalf of the church on one or more social networking sites and providing podcasts for people to listen to.

Despite these commendable uses of technology, Allen (2008) observed that the digital age is nonetheless posing pastoral challenges to the church. He points out that three different communication eras now exist in the same church community, posing a myriad of leadership issues for today's church because of technological and digital divides. Vieira (2012) notes that Pope Benedict VI described technology as having a dual role. It can provide huge opportunities but poses huge challenges at the same time. ICT can either be a service or a disservice. For instance, from the moral perspective, mass media can speak the truth or falsehood, and it can be informative or powerfully manipulative through the flood of news. To ensure technology's optimal contribution to the church, Pope Benedict offered a useful guide. He stated that in order to be a blessing, ICT has to promote human dignity and be inspired by charity in the service of truth, goodness and universal fraternity. Castells (2012), in a nuanced way to Pope Benedict VI, states that ICT has ushered in mass self-communicated networks that are horizontal. This communication is not controlled by influential people but it operates within the ecosystem of the people. Within the church this horizontal communication can spread uncontrollable gossip that can threaten and destroy the building, nurturing and existence of church members. However, as Castells (2012) notes, the powers of structure such as governments and bishops is declining, while the youth and other social groups have found alternative spaces. Therefore technology objectors and those who are sceptical should be conscious of these developments so that technology will be embraced as an ally rather than seen as a foe.

Characterisation of emerging identities from the use of technology in African churches

From the above discussion, the categories and emerging identities of the pastors are summarised in Table 2.

Conclusion

This article discusses the use of technology in churches with a particular focus on the technological changes in the African context. The article then examines the technological situation in Zimbabwe based on an empirical study. In discussing the use of technology in churches, three identities of pastors arising from the increased use of technology in Zimbabwe have been discerned.

The first identity is that of the pastor who is on a par with the world - the technology embracer. The pastor is as sophisticated as the congregation members, and in many instances is far ahead of his members in the use of technology. The pastor is a networker and entrepreneur. This pastor uses technology in an uncontrolled manner, and is an unrestricted technology consumer.

The second identity is that of a pastor who is trailing society and technology. This pastor is a cautious embracer of technology whose use of technology is limited. Technology use is viewed with scepticism by denominational leadership.

The third identity is that of a pastor in isolation - the technology objector. This pastor is unconnected, ignorant and the church is viewed as a place for old people. God is somewhat of an enemy of technology. Technology is viewed as a secular tool with no place in formal worship.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationships which may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

References

Allen, B., 2008, 'Counsellor: Digital age poses pastoral challenges to church', Baptist News Global, viewed 01 April 2013, from http://baptistnews.com/archives/item/3587-counselor-digital-age-poses-pastoral-challenges-to-church [ Links ]

Babbie, E. & Mouton, J., 2006, The practice of social research, Oxford University Press, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Barna Group, 2008, New research describes use of technology in churches, viewed 20 February 2013, from http://www.barna.org/barna-update/article/14-media/40-new-research-describes-use-of-technology-in-churches [ Links ]

Brakel, P.A. & Chisenga, J., 2003, 'Impact of ICT-based distance learning: The African story', The Electronic Library 21(5), 476-486. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/02640470310499867 [ Links ]

Biztechafrica, 2014, Econet: Diversification pays off - Zimbabwe, viewed 20 January 2015, from http://www.biztechafrica.com/article/econet-diversification-pays/9047/?country=zimbabwe#.VMhIq02IrmQ [ Links ]

Castells, M., 2000, The rise of the network society, 2nd edn., Blackwell, Oxford. [ Links ]

Castells, M., 2012, Networks of outrage and hope: Social movements in the Internet age, Oxford University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Chu Ilo, S., Ogbonnaya, J. & Ojacor, A. (ed.), 2012, The church as salt and light: Path to an African ecclesiology of abundant life, Clark, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Dube, C.M., 2010, 'Women entrepreneurs and information communication technology (ICT): An analysis of the efficacy of the use of modern technology in conducting business transactions in Zimbabwe', MLA dissertation, Faculty of Law, University of Zimbabwe, Harare. [ Links ]

Fearon, J.D., 1999, 'What is identity (as we now use the word)?', viewed 04 April 2014, from http://www.stanford.edu/~jfearon/papers/iden1v2.pdf [ Links ]

Filteau, J., 2010, 'Technology for parishes is about relationships', in National Catholic Reporter, viewed 05 April 2013, from http://ncronline.org/printpdf/17464 [ Links ]

Gillwald, A., 2012, 'Understanding broadband demand in Africa: Internet going mobile, broadband as a video platform: Strategies for Africa', Lusaka, viewed 02 April 2013, from http://www.researchictafrica.net/docs/Gillwald%20CITI%20Zambia%20Broadband%202012.pdf [ Links ]

Gillwald, A., Milek, A. & Stork, C., 2010, 'Towards evidence-based ICT policy and regulation - Gender assessment of ICT access and usage in Africa', Volume One, 2010 Policy Paper 5. [ Links ]

Isaacs, S., 2007, 'ICT in education in Lesotho: A survey of ICT and education in Africa', Lesotho Country Report, viewed 10 January 2015, from http://www.infodev.org [ Links ]

Jones, S.J. & Ough, B., 2010, The future of the United Methodist Church, 7: Vision pathways, Abingdon Press, Nashville, TN [ Links ]

Kabweza, L.S.M., 2012, 'Zimbabwe's June 2012 mobile & fixed subscriber stats. 90% tele-density', in TechZim, viewed 04 April 2013, from www.techzim.co.zw/2012/09/zimbabwes-june-12-mobile-fixed-subscriber-stats-90-tele-density/ [ Links ]

Kalu, O., 2008, African Pentecostalism: An introduction, Oxford University Press, Oxford. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195340006.001.0001 [ Links ]

Kitetu, C.W., 2008, Gender, science, and technology: Perspectives from Africa, Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa, Dakar. (Codesria gender series 6). [ Links ]

Kumar, S. & Kar, D.C., 1995, 'Library computerisation: An inexpensive approach', OCLC Systems, Services 11(4), 3-10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/10650759510104970 [ Links ]

Louw, D.J., 1998, A pastoral hermeneutics of care and encounter: A theological design for a basic theory, anthropology, method and therapy, Lux Verbi.BM, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Magezi, V., 2007, HIV and AIDS, poverty and pastoral care and counselling: A home-based and congregational systems ministerial approach in Africa, Sun Media, Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Mandoga, E., Matswetu, V. & Mhishi, M., 2013, 'Challenges and opportunities in harnessing computer technology for teaching and learning: A case of five schools in Makoni East district', International Journal of Humanities and Social Science 3(1), 105-112. [ Links ]

Marshall, C. & Rossman, G.B., 2006, Designing qualitative research, 4th edn., Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA. [ Links ]

Maxwell, J.A., 2005, Qualitative research design: An interactive approach, 2nd edn., Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA. [ Links ]

Mohapi, T., 2014, Technology in Africa: 2014 Digest, Mohapi, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

'New technology versus church', ZBC News, 06 September 2012, viewed 02 February 2013, from http://www.zbc.co.zw/news-categories/blogs-a-features/23433-new-technology-versus-church.html [ Links ]

Ossai-Ugbah, N.B., 2011, 'The use of information and communication technologies in Nigerian Baptist churches', International Journal of Science and Technology Education Research 2(3), 49-57. [ Links ]

Ukodie, A., 2004, ICON of ICT in Nigeria - Their passion, vision and thoughts, ICT Publishers, Lagos. [ Links ]

Use of Technology.com, 2011, How to use technology - 100 advantages of using technology, viewed 05 January 2013, from http://www.useoftechnology.com/how-to-use-technology/ [ Links ]

Vieira, J., 2012, 'Mass Media: Area of apostolate for the church in Africa', in Comboni Missionaries, viewed 30 March 2013, from http://www.combonisouthsudan.org/index.php/bible-reflections/africae-munus/359-mass-media-area-of-apostolate-for-the-church-in-africa [ Links ]

World Bank, 2012, 'Mobile usage at the base of the pyramid in Kenya', InfoDev Publication prepared by iHub Research and Research Solutions Africa, Washington DC. [ Links ]

World Bank and the African Development Bank, 2012, eTransform Africa -The transformational use of information and communication technologies in Africa, viewed 30 March 2013, from http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/TOPICS/EXTINFORMATIONAND COMMUNICATIONANDTECHNOLOGIES/ 0,,contentMDK:23262578~pagePK:210058~piPK:210062~theSitePK:282823,00.html [ Links ]

Zimbabwe - The National Gender Policy, 2013-2017, Ministry of Women Affairs, Gender and Community Development, Republic of Zimbabwe. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Vhumani Magezi

PO Box 1174, Vanderbijlpark 1900, South Africa

vhumani@hotmail.com

Received: 31 Jan. 2015

Accepted: 02 Apr. 2015

Published: 05 June 2015

This article is published in the section Practical Theology of the Society for Practical Theology in South Africa.

1.Missionary-started churches refer to those denominations that were started during the period of the Missionary movement in the early 1900s.

2.Mainline churches largely refer to missionary-started churches.