Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

HTS Theological Studies

On-line version ISSN 2072-8050

Print version ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.71 n.1 Pretoria 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/HTS.V71I1.2905

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

'If those to whom the W/word of God came were called gods ...'- Logos, wisdom and prophecy, and John 10:22-30

Jonathan A. Draper

School of Religion, Philosophy and Classics, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

ABSTRACT

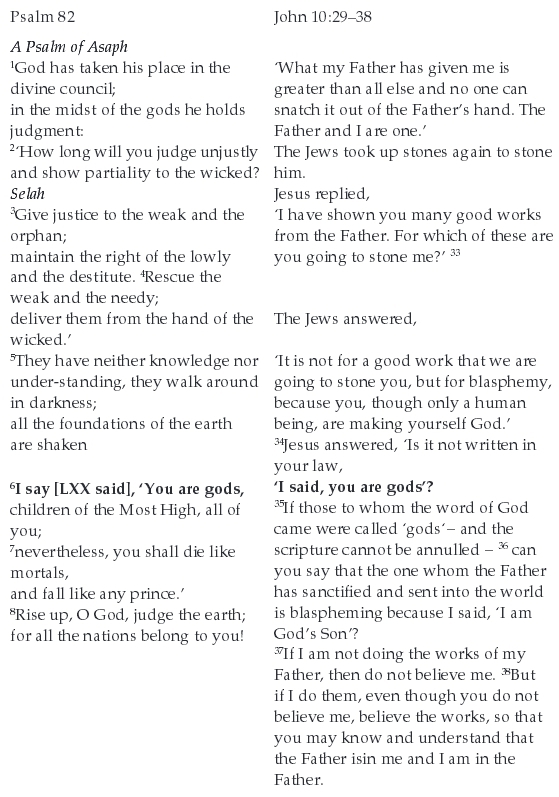

Jesus' quotation of Psalm 82:6, 'I said, You are gods', a riposte to the accusation that he had blasphemed by making himself equal to God, has attracted considerable attention. The latest suggestion by Jerome H. Neyrey rightly insists that any solution to the problem should take account of the internal logic of the Psalm and argues that it derives from or prefigures a rabbinic Midrash on the Psalm which refers it to the restoration of the immortality lost by Adam to Israel at the giving of the Torah on Sinai. This immortality was then lost again because of the sin of the golden calf. Whilst agreeing that the Psalm is interpreted in the context of the giving of the Torah on Sinai, this article argues that its reference is directed towards Moses on Sinai rather than Israel in general. This accords with the interpretation of Philo and Josephus and other sources much earlier than the Mekkilta de Rabbi Ishmael that Moses is rightly called a god and is assumed to heaven in glory without dying. Rather than deny this attribution of divine features to Moses due to his reception of the Torah on Sinai, John argues that the Torah was received from the hands of Jesus as the Logos. Therefore, Moses's derivative divine features simply confirm the true divinity of the Logos as the expression of the Father. Moses could be called a god because he knew Jesus as Logos and wrote about him (5:45-5:47), but he sinned and died like any mortal. The corollary is that Moses and his disciples lost their status and died like any mortal, whilst the disciples of Jesus who are 'taught by God' and believe in the Incarnate Logos (6:45), have not only seen the glory denied to Moses but are born from above to become divinised as tekna theou (1:12) and do not die.

Introduction

In an article given in Brussels a few years ago (Draper 2007), I argued that the relationship between Moses and Jesus is a central consideration for John's Gospel. The Torah was given through Moses, grace and truth through Jesus Christ (1:17). The central issue is the issue of mediation of the knowledge and presence of the unknowable, unseeable God. If God is unknowable and unseeable, how did Abraham receive the Covenant; how did Moses receive the Torah; and how did the prophets receive God's word? In the course of the Gospel, John indicates in turn that Abraham (8:55-8:58), Moses (5:45-5:46), and Isaiah (12:41) all saw Jesus and wrote about him/ wrote his words. Jesus is seen as the dynamic 'only coming into being God', the angelic figure bearing the Name of God who appears between the halves of the sacrifice to Abraham, who appears to Moses on Sinai and mediates the Torah to him, who appears in a vision to Isaiah 'high and lifted up and his train filled the temple'. However, it is the relationship between Jesus and Moses, which most concerns John, because it is Moses who is claimed as the basis for the authority of the opponents of John and his community.

For John, Jesus is the divine figure YHWH who appears to Moses on the rock after direct vision of God's glory is denied Moses; he is the God 'full of grace and truth' (Ex 34:6). John combines traditions of the Name-bearing Angel of the Presence (Enoch-Metatron, Yaoel, Melchizedek, and so on) with the Greek concept of the Logos, to produce an understanding of Jesus, which stands in a different trajectory to that of the Synoptics. There is no hostile opposition between Jesus and Moses; quite the contrary, as Moses saw Jesus and wrote about him (5:45-5:47). Indeed, the gift of the Torah represents the giving of the W/word to Israel, so that the Torah is the words of the Word. Nevertheless, John is careful to signal the subordinate status of Moses and his difference from Jesus. No one has gone up to heaven except the one who came down from heaven, Jesus (3:13), as we shall see, this is a rejection of claims that Moses went up to heaven to receive the Torah. The Torah is not itself life-giving except in as much as it points to the one who is Life and mediates life to those who believe in him (5:39-5:40). The bread supplied by Moses in the desert was a gift from God but did not mediate life, since all died. Only Jesus who came down from heaven could supply bread from heaven which does mediate life, since he is the Life (6:30-6:58). The wilderness generation including Moses died (6:58), as we shall see, a rejection of the claim that Moses did not die but was assumed into heaven. Moses gave the Torah he received from the Logos to the people of Israel and allows circumcision (one body part) to override the Sabbath, but Jesus heals the whole body on the Sabbath (7:19-7:24). Ironically, those who claim to be Moses' disciples say, 'We know that God spoke to Moses, but as for this man [Jesus], we do not know where he comes from' (9:29). Ironical, that is, because Jesus is the God who spoke to Moses and yet Moses' disciples do not recognise Jesus as the one who mediated the Torah to him nor do they know where he came from and so adjudge themselves guilty.

In this article, honouring the work of Pieter de Villiers in the field of Johannine studies over many years1, I take up my hypothesis of the contrast between Moses and Jesus again as the background to John's understanding of the difficult passage, 'I said, "You are all gods"' in John 10:34, a direct quotation from Psalm 82:6 [81:6], seemingly in the Septuagint version. I would like to relate this to the statement in 6:45, 'And you shall all be taught by God', and 1:12, 'But as many as received him he gave them authority to become children of God, to those who believe in his name, who are born not of blood nor of the will of flesh nor of the will of a man but of God'. In this study, I take my starting point from the major study of Moses in John's Gospel by Wayne Meeks, The prophet-king: Moses traditions and the Johannine Christology (1967) and the recent interpretation provided by Jerome H. Neyrey, The Gospel of John in cultural and rhetorical perspective (2009).

Recent studies of John 10:22-30

A small flurry of articles greeted the publication of the text of 11QMelchizedek from the Dead Sea Scrolls, as it presents, in a fragmentary form, a commentary on Psalm 82, in which "elohim is applied to the figure of Melchizedek. The angelic figure of Melchizedek stands in the assembly of the gods to judge the evil spirits of Belial and his lot. John Emerton (1960; 1966), who had already argued that 'elohim in this passage referred to angelic beings found his hypothesis confirmed. However, the editor of the text (Van der Woude 1965; again transcribed and annotated in De Jonge and Van der Woude 1966) rejected this idea as lacking other support in John, particularly as there is no mention of any commissioning of the theoi in the Gospel. Anthony T. Hanson (1965) had also written previously on the passage to argue that the background lies in the rabbinic interpretation of the passage, by which those addressed in Psalm 82 are the people of Israel on Sinai at the giving of the Law, who were addressed by Jesus as the Word. He takes up the passage again in the light of 11QMelchizedek and re-examines the differing traditions of interpretation of Psalm 82 in rabbinic tradition. Whilst some passages do seem to envisage the 'gods' in 82:1, six as angelic beings, they more usually refer the text to the judges appointed by Moses in Deuteronomy 1:15-18, and, by extension, the present day assemblies of Israel for judgement. So, for example, in b.Ber 6a:

It has been taught: Abba Benjamin says: A man's prayer is heard [by God] only in the Synagogue. For it is said: To hearken unto the song and to the prayer. The prayer is to be recited where there is song. Rabin b. R. Adda says in the name of R. Isaac: How do you know that the Holy One, blessed be He, is to be found in the Synagogue? For it is said: God standeth in the congregation of God. And how do you know that if ten people pray together the Divine presence is with them? For it is said: 'God standeth in the congregation of God'. And how do you know that if three are sitting as a court of judges the Divine Presence is with them? For it is said: In the midst of the judges He judgeth. And how do you know that if two are sitting and studying the Torah together the Divine Presence is with them? For it is said: Then they that feared the Lord spoke one with another; and the Lord hearkened and heard, and a book of remembrance was written before Him, for them that feared the Lord and that thought upon His name. (Soncino e-text; cf. Midrash Rabbah Ps 82)

The problem with trying to apply this to John 10:34, is that it does not relate to the logic of John's argument in the text - it is hard to see how describing the judges of Israel as 'gods' justifies Jesus in calling himself the Son of God. Hanson (1965:367) rightly insists that John's use of Scripture should not do violence to its meaning, as John himself says of his quotation, 'and Scripture cannot be broken': 'John does not treat scripture lightly and here he provides us with an explicit scriptural reference' (Hanson 1965:367).

An alternative rabbinic interpretation of the text is that Israel at Sinai was restored to the original state of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden by the giving of the Torah.2 Hence, they were semidivine beings no longer subject to death, which came as a consequence of sin. In a commentary on the Psalm in b.AZ 5a (cf. Mekilta de-Rabbi Ishmael, Tractate Bahodesh 9, in Neyrey 2009:322), Resh Lakish argues along these lines:

Said Resh Lakish: Come let us render gratitude to our forebears, for had they not sinned, we should not have come to the world, as it is said: I said ye are gods and all of you sons of the Most High; now that you have spoilt your deeds, ye shall indeed die like mortals etc. Are we to understand that if the Israelites had not committed that sin they would not have propagated? Had it not been said, And you, be ye fruitful and multiply? -That refers to those who lived up to the times of Sinai. But of those at Sinai, too, it is said, Go say to them, Return ye to your tents which means to the joy of family life? And is it not also said, that it might be well with them and with their children? - It means to those of their children who stood at Sinai. (Soncino e-text)

In other words, immortality was restored to Israel at the giving of the Torah, only to be removed again because of the idolatry of the Golden Calf.3 They were all called gods but all died like mortals as a result of sin. James Ackerman (1966) sees in this a link to the myth of Wisdom whose dwelling with human beings guaranteed their immortality, but whose return to heaven after the Fall led to human mortality. This rabbinic interpretation was not without challenge in the tradition, by Rabbi Jose (A3) and R. Simeon b. Lakish who argue rather that the passage promises that as long as they kept the Torah, Israel would never be defeated by her enemies. Nevertheless, all agree that the Psalm refers to the giving of the Torah on Sinai and that the gift of Torah was the occasion of the gift of life or immortality in some way to Israel. This, according to Hanson, is the only rabbinic interpretation, which makes sense of the interpretation presupposed by John.

The interpretation is also supported by Paul's enigmatic statement in Romans 5:14, which confirms that this interpretation is current in the first century also and therefore would probably be known to John. In the dispute over 'the type of the one to come',4 it seems to have been overlooked that Paul says, 'But death reigned from Adam until Moses'. He does not say that death reigned from Adam until Jesus. In my opinion, Paul the Pharisee is repeating an exegesis so common in the circles in which he was schooled that he sees no need to elaborate. He does not even notice the possible contradiction this introduces within his overall argument. If death reigned only until Moses, then the gift of the Torah and the covenant through Moses to Israel overturned the sin of Adam and restored the original state of human immortality as created in the image of God and therefore in some sense divine (though only for Israel). Paul is the earliest witness to the exegesis found in the Rabbis. Nevertheless, like them and like John, Paul obviously assumes that the immortality momentarily conferred at Sinai was lost through the disobedience of Israel (and Moses) which meant that they and their descendants died and that the 'grace of the one man Jesus Christ' was needed to restore the gift of life to human kind.

Taking his cue from Hanson's interpretation of the rabbinic Midrash, Jerry Neyrey (2009:313-331) rightly insists on the importance of taking equal account of the rhetoric of John's argument. He sees two 'forensic proceedings' in 10:1-28a and 10:28b-39. The first charge requires Jesus to answer the question plainly, as to whether he is the Messiah (10:24), which Jesus turns around as an accusation against them of failing to hear his voice as the shepherd of Israel. The second 'forensic proceedings' accuse Jesus of 'making himself equal' to God.5 Neyrey points, correctly, to the parallel between Jesus' action in 10:28 and the Father's action in 10:29 which are described in exactly the same terms, Jesus and the Father both give eternal life to those who believe and none can snatch them from their hand; thus, bearing out the charge of blasphemy laid against Jesus by the 'Jews' (Judaean authorities). This raises two questions: does Jesus make himself God or equal to God? And if so in what sense? (Nerey 2009:320).

Neyrey's (2009:324) answer begins by clarifying the various versions of the rabbinic Midrash on Psalm 82, which show:

• its connection with Sinai and the giving of the Torah

• Israel's obedience

• led to deathlessness and immortality

• so that they were rightly called god.

Thus, the relation between holiness and immortality and divine status (in God's image) established in Adam is re-enacted on Sinai when the people become holy and immortal and so are rightly called gods; the Fall of Adam and his subjection to death is re-enacted after the incident of the Golden Calf by the people at Sinai who die like mortals:

First, the historical occasion of Psalm 82 is regularly seen to be Israel's reception of God's word at Sinai. Second, the Midrash does not call Israel god for purely extrinsic reasons, but links godlikeness with holiness and so deathlessness. Finally, even the simple Midrash assumes some biblical notion of death and deathlessness, which implies an understanding of Genesis 1-3 or some popular myth of the origin of death in the world. (Neyrey 2009:326)

From this, Neyrey moves to show that being called gods is limited by John to 'those to whom the word of God came', thus setting up an implicit link with the giving of the Torah on Sinai. Moreover, the citation comes in the context of an assertion by Jesus that he (and the Father) give eternal life to those who believe and that 'no-one can snatch them from Jesus' (and the Father's) hand, echoing the rabbinic discussion about the restraining of the Angel of Death'. In this context, the reception of the Word of God in obedience brings holiness and facilitates 'passing to eternal life' (Neyrey 2009:326). Then if this applies to Israel (and Jesus' disciples), how much more does Jesus' holiness and sinlessness provide grounds for calling Jesus God. Jesus is consecrated by God and absolutely obedient to him, so that far from being a sinner or a blasphemer, he is God's Holy One and as such has power over death and is rightly one with the Father (Neyrey 2009:327-329). Thus, the charges laid against him by the Judaean authorities are baseless.

Neyrey's discussion is a helpful step forward in the interpretation of this difficult passage in John. However, I am not convinced that the reference to those called gods because the word of God came to them rightly applies to 'all Israel' at Sinai. The rabbinic Midrashim are certainly important and show that the Psalm was applied to the reception of the Torah at Sinai. The alternative Midrashic interpretation concerning of the appointing of judges by Moses also points to the reception of the Torah at Sinai. This must certainly be the starting point of any discussion of the use of Psalm 82 in John 10:34-36. Yet, I would like to raise again the question as to who exactly the one(s) were 'to whom the w/Word of God came' on Sinai who might as a result be called god(s). The reference to Israel's divine status through the Torah is largely metaphorical, not intrinsic. There are no claims made anywhere that all Israel became angels or gods. However, Moses, to whom the w/Word of God came, certainly was called a god in many texts: Moses went up to heaven, spoke face-to-face with God, learned the divine mysteries, was transfigured in glory and after delivering the Torah and leading his people to the Jordan was taken up to heaven to be with God without facing death. A focus on this theme as the background to John 10:22-30 has the advantage that it takes up a consistent theme in John's Gospel, namely the claims of the Judaean authorities to be disciples of Moses and Jesus' insistence that they cannot be called Moses' disciples if they do not do what he did, namely recognise and accept the Word.

Moses on Sinai in Philo, Josephus and other Hellenistic Jewish writers

It is Wayne Meeks's distinctive contribution in The prophet-king: Moses traditions and the Johannine Christology (1967), perhaps stimulated by the debate we have been charting, to have raised first the question of the distinctive role of Moses in John's Gospel. He provides a substantial outline of the depiction of Moses in contemporary sources outside of the gospel, against which John's depiction must be measured. So here, it is not necessary to do more than summarise his findings, though his treatment is limited by a narrow Christological frame of reference.

Moses in Philo

Meeks (1967:102), following Goodenough (1935), argues that Philo was part of a much larger movement. I personally think that his contribution was more original than they allow, especially in the thoroughgoing exploration of a (neo-) Platonic reading of Scripture. Nevertheless, there is ample evidence that the main lines of his interpretation have roots in earlier Jewish discussions. For our purposes, it is important to note that there seems to have been something of an attempt to exalt the figure of Moses as a counter to trajectories within Israelite culture which exalted Enoch, Melchizedek, Yaoel and other angelic figures (see Orlov 2005:254-303). Philo may be reflecting this struggle, but in his own way even promotes it (as he does in identifying Melchizedek with the Logos). In any case, Meeks is right to comment that Philo sees Moses 'as something more than an ordinary human being'. In QE ii.54, he is 'the divine and holy Moses' (Meeks 1967:103). From his birth, Moses raised speculation as to whether he was 'human or divine or a mixture of both' (Mos 1:27). Philo takes Exodus 7:1 literally to argue that Moses is a god:

'I give thee,' He says, 'as god to Pharaoh' (Exod. vii. 1); but God is not susceptible of addition or diminution, being fully and unchangeably himself. And therefore we are told that no man knows his grave (Deut. xxxiv.6). For who has powers such that he could perceive the passing of a perfect soul to Him that 'IS'? Nay I judge that the soul itself which is passing thus does not know of its change to better things, for at that hour it is filled with the spirit of God. (Sac III.9-20 Loeb Classical Library)6

As he is a god, Moses does not die but is taken up to God. This takes up a widespread myth concerning the death of Moses: that as his grave is not known and that he did not actually die but was assumed directly into heaven. His report of his own death was to stop rumours of divinity!

In this context, it is crucial to note the basis on which Moses is declared a god, namely his reception of the Logos: Philo introduces and follows the above comments on Moses with a discussion of Cain and Abel as 'two opposite and contending views of life', the one oriented to self and the other to God. Abraham is mentioned first as an example of the man oriented to God and he is divinised:

So too, when Abraham left this mortal life, 'he is added to the people of God' (Gen. xxv.8), in that he inherited incorruption and became equal to the angels (ϊσος άγγέλοις γεγονώς), for angels -those unbodied and blessed souls - are the host and people of God. (Sac III.5, LCL)

Jacob and Isaac also follow this pattern. They might all be called 'gods', as angels may be described in this way. However, Moses is properly called a god because the Word comes to him on Sinai (together with 'still others' to whom the Word of God came):

There are still others, whom God has advanced even higher, and has trained them to soar above species and genus alike and stationed them beside himself. Such is Moses to whom he says 'stand here with Me' (Deut. v.31). And so when Moses was about to die we do not hear of him 'leaving' or 'being added' like those others. No room in him for adding or taking away. But through the 'Word' (δια ρήματος) of the Supreme Cause he is translated (Deut. xxxiv.5), even through that Word (δι' ού) by which also the whole universe was formed. Thus you may learn that God prizes that Wise Man as the world, for that same Word (τω αύτω λόγω), by which he made the universe, is that by which He draws the perfect man from things earthly to Himself. (Sac III.8, LCL)

Moses is a god to Pharaoh, but he is only one of others who are rightly called gods by God, namely those to whom the Word comes and 'draws the perfect man from things earthly to Himself'. Despite the attribution of the LOEB edition of 'stand here with Me' to Deuteronomy 5:31, it is very reminiscent of God placing Moses on the rock before YHWH passes by, and matches what Philo says elsewhere:

What does He say, 'Moses alone shall come near to God, and they shall not come near, and the people shall not go up with them'? O most excellent and God-worthy ordinance, that the prophetic mind alone should approach God and that those in second place should go up, making a path to heaven, while those in third place and the turbulent characters of the people should neither go up above nor go up with them but those worthy of beholding should be beholders of the blessed path above. But that '(Moses) alone shall go up' is said most naturally. For when the prophetic mind becomes divinely inspired and filled with God, it becomes like the monad, not being at all mixed with any of those things associated with duality. But he who is resolved into the nature of unity, is said to come near God in a kind of family relation, for having given up and left behind all mortal kinds, he is changed into the divine, so that such men become kind to God and truly divine. (QE II.29, LCL)

As the 'friend of God' Moses is given the same name as God:

For he was named god of the whole nation, and entered, we are told, into the darkness where God was, that is into the unseen, invisible, incorporeal and archetypal essence of existing things. Thus he beheld what is hidden from the sight of mortal nature, and, in himself and his life displayed for all to see, he has set before us, like some well-wrought picture, a piece of work beautiful and godlike, a model for those who are willing to copy it. (Mos I.158, LCL)

There is no doubt in my mind that Philo himself, who never comments on Psalm 82:6, would have understood 'I said, "You are gods"' with reference to Moses as the friend of God, together with the 'others' who are rightly called gods. Amongst the latter must rank Abraham and Melchizedek. Their divinisation is the result of their reception of the Logos. There is no doubt either that Philo associates this status of Moses with his reception of the Torah on Sinai, which for Philo is the reception of the Logos:

But it is the special mark of those who serve the Existent (τò öν) ... [that they should] in their thoughts ascend to the heavenly height, setting before them Moses, the nature beloved of God, to lead them on the way. For then they shall behold the place which in fact is the Word, where stands God the never changing, never swerving, and also what lies under his feet like 'the work of a brick of sapphire, like the form of the firmament of the heaven' (Ex. xxiv.10), even the world of our senses, which he indicates in this mystery. For it well befits those who have entered into comradeship with knowledge to desire to see the Existent if they may, but if they cannot, to see at any rate his image, the most holy Word, and after the Word its most perfect work of all that our senses know, even this world. (De Confus 1.97, LCL)

This in itself raises intriguing questions with regard to John's argumentation in 10:22-30, particularly as, for Philo, Moses beholds the Logos and others may, through his example, also behold it, put beneath them the material world, and be divinised in the same way.

Moses in Josephus

Whilst Josephus is more guarded in his description of the divine status of Moses, he also accepts the idea that Moses did not die but was assumed into heaven:

And while he bade farewell to Eleazar and Joshua and was yet communing with them, a cloud of a sudden descended upon him and he disappeared in a ravine. But he was written of himself in the sacred books that he died, for fear lest they should venture to say that by reason of his surpassing virtue he had gone back to the Deity. (Ant IV.326, LCL)

However, because of the danger that Moses might be worshipped instead of God himself, his assumption into heaven is disguised by Moses himself!

Other contemporary texts

In his analysis of this trend towards the exaltation ofMoses, Andrei Orlov (2005:200-276) mentions also 2 Baruch 59:5-12 and several other Midrashim (Midrash Tadshe 4; Genesis Rabbah 11). A particularly important testimony to the divine or semidivine status of Moses in Jewish texts roughly contemporary with John's Gospel, Ezekekiel the Tragedian, Exagoge 67-90 (Alexandria, 2nd century BCE) describes a vision of Moses enthroned on Mount Sinai as king and with the star parading before him. The angel Raguel tells Moses that this is a prophetic vision of what is to come. Moses will see not just earth but also the mysteries of heaven; not just the present, but also the past and the future:

Moses: I had a vision of a great throne on the top of Mount Sinai and it reached till the folds of heaven. A noble man was sitting on it, with a crown and a large scepter in his left hand. He beckoned to me with his right hand, so I approached and stood before the throne. He gave me the scepter and instructed me to sit on the great throne. Then he gave me a royal crown and got up from the throne. I beheld the whole earth all around and saw beneath the earth and above the heavens. A multitude of stars fell before my knees and I counted them all. They paraded past me like a battalion of men. Then I awoke from my sleep in fear.

Raguel: My friend this is a good sign from God. May I live to see the day when these things are fulfilled. You will establish a great throne, become a judge and leader of men. As for your vision of the whole earth, the world below and that above the heavens- this signifies that you will see what is and what has been and what shall be. (Text in Orlov 2005:262)

A similar vision of the enthronement of Moses is found in Numbers Rabbah 15:13 (cited by Meeks 1967:193). To these Orlov adds Pseudo-Philo, Biblical Antiquities 12:1:

Moses came down (having been bathed with light that could not be gazed upon, he had gone down to the place where the light of the sun and moon are. The light of his face surpassed the splendour of the sun and the moon, but he was unaware of this. When he came down to the children of Israel, upon seeing him they did not recognize him. But when he had spoken, then they recognized him. (Text in Orlov 2005:268)

All in all, it is clear that there was a widespread tradition that the reception of the Torah on Sinai conferred a special divine status on Moses, which included a tradition of his enthronement, assumption to heaven to receive the Torah and his final re-ascent to God without dying.

This account was resisted by the Enoch(-Metatron) tradition, according to Andrei Orlov (2005:255-260). The Enoch tradition accepts but downplays the significance of the conferral of the Torah on Moses at Sinai. Particularly important for our study is the text of 1 Enoch 89:29-32:

29And that sheep ascended to the summit of that lofty rock, and the Lord of the sheep sent it to them.30 And after that I saw the Lord of the sheep who stood before them, and His appearance was great and terrible and majestic, and all those sheep saw Him and were afraid before His face. 31And they all feared and trembled because of Him, and they cried to that sheep with them [which was amongst them]: 'We are not able to stand before our Lord or to behold Him.'32 And that sheep which led them again ascended to the summit of that rock, but the sheep began to be blinded and to wander from the way which he had showed them, but that sheep wot not thereof.33 And the Lord of the sheep was wrathful exceedingly against them, and that sheep discovered it, and went down from the summit of the rock, and came to the sheep, and found the greatest part of them blinded and fallen away (Charles).

Here, Moses is simply a sheep to whom the glorious and terrifying Lord of the Sheep sends the Torah, and his failure along with that of the people of Israel in the affair of the Golden Calf is highlighted. He does not ascend to God but 'falls asleep'/dies like the other leaders of Israel. This downplaying of the role of Moses in the reception of the Law before the glorious one who gives it to him (who may be equated with Enoch, perhaps) is associated with an understanding of Enoch as the primary mediator of divine revelation and knowledge. Moses is not the primary mediator but simply the receiver. In the light of the occurrence of our text in John's depiction of Jesus as the Good Shepherd and those who follow him as sheep, this is an evocative text. It would seem that the interpretation of Psalm 82:1 in 11QMelchizedek, which we have already noted, falls into the same tradition: whereas the role of Moses is not denied, the true revealer, also called a god, is Melchizedek. "Elohim in Psalm 82:1 is interpreted as the divine figure of Melchizedek who will judge the wicked and who will atone for and liberate God's people from the power of Belial (elsewhere called Melchira') and his spirits, who are seen as the other referent of the verse. Sadly, the fragmentary state of the text deprives us of much else.

Psalm 82 in John 10:22-30

In recent years, the Jewish mystical tradition which envisages multiple derivative divinities and 'open heaven' has attracted a great deal of attention.7 The presence of the mystical and angelic liturgical texts among the Dead Sea Scrolls has placed the tradition firmly in the Second Temple period, and so opened up the likelihood that some of the New Testament texts may know and use the tradition or, for that matter, polemicize against it. Against the background of this multifarious and competitive context of competing claims for the derivative divinity of one or other of the figures in Israel's heritage, John's interpretation of Psalm 82 in 10:22-30 is less startling. John stands in the same tradition, close so often to the sectarian texts from Qumran in many respects8 but undercutting their worldview at the same time through his concept of the Logos. With this as the context in which John is writing, we can now examine John 10:22-30 more closely.

Against the background of the tendency to call Moses a god in Second Temple Jewish thought, in contrast to a tradition which sees the more important figure as Enoch-Metatron or the angel Yaoel or Melchizedek, it would seem not inappropriate to ask whether the quotation from Psalm 82:6, 'I have said: You are gods', is applied to Moses, or to a small group including Moses, rather than to all Israel. As we have seen, Moses plays an important role in John's Gospel, always in a subordinate role to Jesus: 'The Torah was given through Moses, grace and truth through Jesus Christ'. Who gave Moses the Torah is the question I addressed in my previous article (2007), and my conclusion was that John understands that it was Jesus who is the YHWH figure who comes down on Sinai, the Name-bearing angelic figure promised by God who would go with his people from Sinai. It is Jesus as the pre-existent creative Word. Jesus is the Logos spoken by God which brought light and so life to the chaos and which remains shining in the darkness of chaos which has failed to extinguish it, which continues to work sustaining creation even as the Father works. Moses saw Jesus and wrote of him. The Logos came to Moses and he wrote down the Torah at his 'direction' which is about Jesus as the Logos incarnate (5:45-5:47). Based on this, Moses is called a god; his face shines with the glory of the theophany and must be covered with a veil. He is not the only one to whom the Word came, according to John's Gospel. The Word came also to Abraham (8:56). Abraham too, then, may be described as a god like Moses. The Word came also to Isaiah, who saw Jesus and wrote about the Lord high and lifted up on the Throne (12:41). Isaiah on these terms might also be described as a god - since no human being can see God and live according to Exodus 33:20 and re-enforced by John 1:18. Perhaps also Jacob (1:51). Perhaps also Elijah and Ezekiel -though they are nowhere mentioned in John's Gospel. In fact, perhaps all of the prophets to whom the Word of God comes could be called gods. In other words, since those to whom the Word of God came are rightly called gods (as it says in Scripture and Scripture cannot be broken), John concedes what is claimed by the Jewish mystical tradition with which the Pharisees were familiar and affirmed, perhaps, concerning Moses and others - that they are (in some way) gods. However, for John they are gods only because the divine Logos, who was with the Father from eternity and was the creative Word of the Father, mediated the Word to them. The other half of the text from the Psalm is equally important for John: 'Nevertheless they shall die like mortals'. This is emphasised also in John 6, where they eat manna and die in the wilderness, et cetera. In my hypothesis, this implied second half of the Psalm citation is a riposte to those who claim both the divine status of Moses and his immortality as one assumed into heaven.

If my suggestion is correct, then the citation of the Psalm is a cogent and persuasive argument. If the Judaean authorities rightly believed that Moses was a god as the recipient of the theophany on Sinai at the giving of the Law - and that there were others too, such as Abraham, to whom such a theophany was given - and these authorities also understood the Psalm in this way, then the question would be:

How could the one who gave the Torah to Moses on Sinai as the Logos of God, through whom Moses is rightly called a god, be accused of blasphemy when he calls himself Son of God and one with the Father?

Moses was 'divinized' by the Word but sinned and grumbled against God and was refused entry into the Promised Land. Consequently he died like any mortal. We have shown that such an understanding of Moses was widespread in the 1st century CE and that John sees Jesus as YHWH, the coming into being God (μονογενής θεός 1:18) who bears the Name of God (see, e.g., 12:28) and gives the Torah to Moses on Sinai. The Judaean authorities claim to be disciples of Moses but do not understand how Moses came to receive the Torah from the Logos. They falsely assert Moses' immortality and assumption into heaven, but fail to see that he died like any other mortal. They search the Scriptures of Moses, thinking to find life in them, but failing to see that the Word and therefore the life comes from the Logos.

So of us it is said, 'They will be taught by God'

If, then, John agrees that it is rightly said of those to whom the Word of God comes that they are gods, what is the implication for the community of John. It seems as if this is a consistent theme in John's Gospel and has important implications for how community members perceived themselves. Of those who believe in Jesus it is said that, 'We have seen his glory, glory as of the only coming into being God'. Whereas Moses was not allowed to see that glory and even so his face shone with the reflected glory of God, members of this community have seen it and are in some way transformed existentially by that. It is also said of them that they are all, like Moses, taught by God, in the tightly organised unit presented by John 6:44-51. To come to Jesus is to be taught by God, to learn from the Father. To come to Jesus and be taught by God is to be raised up on the last day, to have eternal life, because one has eaten the divine Word:

1A. No one can come to me

B. unless drawn by the Father who sent me;

C. and I will raise that person up on the last day.

2B. It is written in the prophets,

'And they shall all be taught by God.'

B. Everyone who has heard and learned from the Father

A. comes to me.

B. Not that anyone has seen the Father

F. except the one who is from God;

B. he has seen the Father.

C. Very truly, I tell you,

whoever believes has eternal lie

C. 48 I am the bread of life

3D. Your ancestors ate the manna in the wilderness,

E. and they died

F. This is the bread that comes down from heaven,

D. so that one may eat of it

E. and not die

4F. I am the living bread that came down from heaven.

D. Whoever eats of this bread

C. will live forever;

C. and the bread that I will give for the life of the world is my flesh.' (Jn 6:44-51 NRS)

Although it is obviously part of a much bigger narrative of the Feeding of the five thousand, the structure of this discourse is highly significant:

A. Coming to Jesus means

B. being drawn, taught, spoken to, seeing the Father which results in

C. receiving Life, beings raised on the last day; those who

D. ate earthly manna in the wilderness

E. died,

F. but because Jesus is the Word who comes down from God, the bread which comes down from heaven

D'. those who eat Jesus

C'. receive Life.

Those who believe in Jesus as God's Logos, now incarnate in the flesh, are 'taught by God' as promised in Isaiah 54:13 (the probable source of the Scriptural citation) in John 6:45; they are those to whom the Word has come (they 'have seen his glory' 1:14), indeed who eat the divine Word, and so are also rightly called (in that limited sense) gods. So it is logical that they should be called 'children of God' (τέκνα θεοΰ 1:12): 'But to all who received him, who believed in his name, he gave power to become children of God, who were born, not of blood or of the will of the flesh or of the will of man, but of God' (Jn 1:12-13 NRSV). In other words, the idea that those who believe in Jesus will not die as they have already entered into eternal life has its roots in the understanding we have seen expressed in John 10:34-36. Whether he knew the tradition or not, John would not disagree with the fundamental premises found in the rabbinic Midrash on Psalm 82 that receiving the Word on Mount Sinai in some way briefly divinised the recipients and hence gave them eternal life which they subsequently lost, but from the same premise he draws radical conclusions for the existential status of members of his community based on their 'eating of the divine Word' (cf. Draper 2013).

Conclusion

The internal logic and coherence between the citation of Psalm 82 in John's Gospel and its use to defend Jesus' assertion of unity with the Father has its pivot point in the story of the reception of the Torah by Moses on Sinai. In this John draws on traditions of interpretation which attributed to Moses the status of a god enthroned in glory, who ascends to heaven to receive the Torah from God and at the end of his life was assumed up to God from Mount Nebo, so that he does not die. His interpretation presupposes such an interpretation, but points out that Moses received it at the hands of (the angel of) YHWH, who is God's Logos. Because of his sin of grumbling against God, he dies like any human being despite the temporary divinity he received by the theophany which made his face shine. Most important is that Moses is called a god because he received the Torah from the hands of Jesus-Logos as 'one to whom the Logos came', but afterwards died like any human being (because of his sin). Since Moses derives the title 'god' from the Logos sent from the Father and incarnate in Jesus, it is ludicrous, says John, to accuse Jesus of blasphemy for calling himself one with God, and Son of God. The argument is not only a case of qal wachomer but refers to the Jesus and Moses respectively as the Revealer and the one who received the revelation. The corollary is that those who, like Moses, received the Word from Jesus and so are the ones to whom the Word came, are also rightly called children of God and receive eternal life from the Source of Life, the Logos. They share in a derivative sense in his divinity.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationships which may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

References

Ackerman, J., 1966, 'The Rabbinic interpretation of Psalm 82 and the Gospel of John', Harvard Theological Review 59, 186-191. [ Links ]

Bible Works 10: Software for Biblical Exegesis and Research, 2015, DVD, Bible Works, Norfolk. [ Links ]

Charlesworth, J.H., 1972, John and Qumran, Chapman, London. [ Links ]

DeConick, A., 2006, Essays on Early Jewish and Christian Mysticism, SBL Press, Atlanta/Brill, Leiden. (Symposium Series 11). [ Links ]

De Jonge, M. and van der Woude, A.S., 1966, '11 Q Melchizedek and the New Testament', New Testament Studies 12, 301-326. [ Links ]

Draper, J.A., 2007, 'Ils virent Dieu, puis ils mangèrent et burent (Exode 24:11): L'immanence mystique du dieu transcendant dans la creation, la théophanie et l'incarnation dans l'étrange Jésus de l'évangile de Jean', in B. Decharneux & F. Nobilio (eds.), Figures del'étrangeté dans l'évangile de Jean: Etudes socio-historiques et littéraires, pp. 237-281, Editions Modulaires Européennes/FNRS, Cortil-Wodon, PA. [ Links ]

Draper, J.A., 2013, 'The metaphor of the vine in John 15 and the early Christian tradition: Reflections on postcolonial critiques', in M. Lang (ed.), Ein neues Geschlecht: Entwicklung des frühchristlichen Selbstbewusstseins, pp. 53-80, Van den Hoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen. (NTOA/ StUNT 105). [ Links ]

Emerton, J.A., 1960, 'Some new testament notes', Journal of Theological Studies 11, 329-332. [ Links ]

Emerton, J.A., 1966, 'Melchizedek and the Gods: Fresh evidence for the Jewish background of John X.34-36', Journal of Theological Studies 17, 400-401. [ Links ]

Goodenough, E.R., 1935, By light light; The mystic Gospel of Hellenistic Judaism, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT. [ Links ]

Hanson, A.T., 1965, Jesus Christ in the Old Testament, SPCK, London. [ Links ]

Jewett, R., 2007, Romans: A commentary, Hermeneia, Fortress Press, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Knight, J. & Sullivan, K., 2015, The Open Mind: Essays in Honour of Christopher Rowland, Bloomsbury, London. [ Links ]

Leaney, A.R.C., 1966, The Rule of Qumran and its Meaning: Instroduction, translation and commentary, SCM, London. (NTL). [ Links ]

Meeks, W., 1967, The prophet-king: Moses' traditions and the Johannine Christology, Brill, Leiden. (SNT 14). [ Links ]

Neyrey, J.H., 2009, Gospel of John in cultural and rhetorical perspective, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Orlov, A.A., 2005, The enoch-metatron tradition, Mohr Siebeck, Tubingen. [ Links ]

Rowland, C.D., 1982, The Open Heaven: A Study of Apocalyptic in Judaism and Early Christianity, Crossroad, New York, NY/ SPCK, London. [ Links ]

Rowland, C.C. & Morray-Jones, C.R.A., 2009, The Mystery of God: Early Jewish Mysticism and the New Testament, Brill, Leiden. (CRINT 12). [ Links ]

Schäfer, P., 2009, The Origins of Jewish Mysticism, Mohr-Siebeck, Tübingen. [ Links ]

Segal, A.F., 1977, Two powers in heaven: Early Rabbinic reports about Christianity and Gnosticism, Brill, Leiden. (SJLA). [ Links ]

The Dead Sea Scrolls: Electronic reference library 2, 1999, DVD, ed. E. Tov, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

The Soncino Classics Collection, 1991-2004, DVD, Soncino Press/Davka Corporation, Chicago, IL. [ Links ]

Thomas, S.I., 2009, The "mysteries" of Qumran: Mystery, secrecy, and esotericism in the Dead Sea Scrolls, SBL, Atlanta. (SBLEJL25). [ Links ]

VanderKam, J., 1984, Enoch and the growth of an apocalyptic tradition, Catholic Biblical Association of America, Washington, DC. (CBQ Monograph 16). [ Links ]

Van der Woude, A.S., 1965, 'Melchisedech als himmlische Erlösergestalt in den neugefundenen eschatologischen Midraschim aus Qumran Höhle XI', Old Testament Studies 14, 354-373. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Jonathan Draper

42 Cordwalles Road, Wembley

Pietermaritzburg 3201

South Africa

draper@ukzn.ac.za

Received: 05 Feb. 2015

Accepted: 02 Mar. 2015

Published: 01 July 2015

1. This article was originally given at a joint international conference in Brussels (20-22 September 2010) between the 'John and Spirituality' sub-group of the New Testament Society of Southern Africa, of which Professor de Villiers was co-chair, and the Centre Interdisciplinaire d'Étude des Religions et de la Laïcité of the Université Libre de Bruxelles, entitled Prophétisme, Sagesse et Esprit dans la littérature johannique/Prophecy, Wisdom, and Spirit in the Johannine Literature.

2.The connection with Adam as created in the image of God is explicitly stated in a variant to the Midrash provided in Numbers Rabbah 16:4 (provided by Neyrey 2009:324).

3. This interpretation finds its anti-Semitic equivalent in the exegesis of the Epistle of Barnabas, 'But they thus finally lost it [the covenant], after Moses had already received it. For the Scripture saith, "And Moses was fasting in the mount forty days and forty nights, and received the covenant from the Lord, tables of stone written with the finger of the hand of the Lord; but turning away to idols, they lost it"' (Brn 4:7 APE on Bible Works 8).

4. For a recent summary of the literature, see Robert Jewett's monumental commentary, Romans: A commentary (2007).

5. I do not consider it appropriate to equate 'one with God' with 'equal with God' as Neyrey does. This seems to me to go further than the evidence warrants, influenced by later Trinitarian hypotheses.

6. Quotations of Philo and Josephus are taken from the Loeb Classical Library (LCL).

7. Pioneers in the field were Alan Segal (1977), Christopher Rowland (1982) and VanderKam (1984). More recently, publications have proliferated with major studies by, among others, Peter Schàfer (2009), Rowland and Morray-Jones (2009), Samuel I. Thomas (2009) and edited collections, such as DeConick (2006) and Knight and Sullivan (2015).

8.This affinity between John and the Dead Sea Scrolls was noted early on by A.R.C. Leaney (1966) and was the subject of a collection of essays by Charlesworth (1972), but has since fallen off the scholarly agenda.