Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

HTS Theological Studies

On-line version ISSN 2072-8050

Print version ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.71 n.1 Pretoria 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v71i1.2860

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Reframing Paul's sibling language in light of Jewish epistolary forms of address

Kyu Seop Kim

Department of Divinity and Religious Studies, University of Aberdeen, United Kingdom

ABSTRACT

Recent scholars focus mainly on Paul's use of 'brothers (and sisters)' or 'brother (and sister)' in Greco-Roman epistolary conventions and cultural backdrops. However, Jewish dimensions (particularly ethnic dimensions) of Paul's sibling language still remain unexplored in current scholarship. Furthermore, scholars have not drawn much attention to how Jewish letter writers use sibling terms in their letters. This article offers a new interpretation on Paul's sibling language in light of its Jewish usage. We should note that Jewish letter writers did not address their Gentile letter recipients as 'brother(s)'. However, Paul did call his recipients 'brothers'. It is unlikely that Paul employed sibling language without being aware of its common Jewish usage. The author proposes that Paul's sibling language is used in the context of an ethnic insider designation (shared ethnicity), and that ascribing the title of brother to believers including Gentiles signals the re-definition of the family of Abraham.

Introduction

Scholars have predominantly focused on the usage of 'brothers' or 'brother' in light of the Greco-Roman epistolary conventions and cultural milieus.1 They conclude that, through sibling language, Paul intends to enrich group solidarity, to emphasise the emotional attachment between fellow believers and also to exhort fellow believers to respect one another in a mutually supportive way (e.g. Horrell 2001:309; Schàfer 1989:321).2 In this context, sibling language in Paul's letters implicitly expresses an in-group identity of the believers in Christian groups distinguishing them from outsiders (Trebilco 2012:67; cf. Meeks 1983:85; Harland 2005:491).

Yet, whereas sociological explorations of Paul's sibling language in the context of the Greco-Roman background are beneficial, detailed research on sibling language has yet to be made in the context of its Jewish usage and, particularly, Jewish epistolary forms of address, except for Taatz and Doering.3 Aasgaard writes, 'this [Jewish] background probably does not tell us much about ... the semantic contents of the metaphor' (2004:115), and maintains that the evidence supporting a Jewish origin is limited (2004:116). Can we then understand Paul's intention in using sibling language in the context of its Jewish usage? What were the social functions of sibling language in Jewish society? Doering (2012:396-397) observes ethnic dimensions of sibling language in ancient Jewish letters and concludes that sibling language was applied to 'people belonging to the same ethnic group.' However, he does not develop this aspect further in his monograph. So, it is still unclear whether Jews used sibling language to their Gentile letter recipients in their letters. Did Jews address their Gentile letter recipients as brothers in ancient Jewish letters? If Jews avoided addressing their Gentile recipients using sibling language, what did this mean? In this context, further research into the meaning of sibling language within the background of Jewish literature and correspondence is justified.

Ethnic implications of sibling language in the Old Testament and Jewish literature

In the Old Testament (OT) and Jewish literature, ΠΝ or αδελφός [brother] can be defined at least in three senses. Firstly, ΠΝ (and αδελφός) essentially refers to a physical brother.4 Secondly, ΠΝ and αδελφός are also utilised when referring to a neighbour or a close friend. For example, in Joseph and Aseneth 8:1, when Pentephres introduces Joseph to Aseneth, Pentephres addresses Joseph as Aseneth's brother in order to highlight his close relationship with Joseph. In the Testament of Abraham 2:5, Abraham addresses an angel as his brother. In particular, the concept of closeness is reinforced with the expression, 'come, draw near to me' (T.Abr 2:5; see also LAB 62:8).

Thirdly, in many instances in the OT and Jewish literature, ΠΝ and αδελφός also refer to a kinsman or a fellow Israelite. In ancient Jewish literature, Jews are described as being 'brother(s)' of their fellow Jews. In the context of the uses of sibling language (i.e., metaphorical sibling terminology and sibling address), this study puts forth two claims in this section: (1) in Jewish letters, sibling language is applied only to Jews; and (2) in Jewish letters, sibling language is not applied to Gentiles.

Firstly, Jews are described as 'brothers' (metaphorical sibling terminology) of their fellow Jews in the OT and Jewish literature. In Exodus 2, a Hebrew is described as Moses' brother:

One day, after Moses had grown up, he went out to his people and saw their forced labour. He saw an Egyptian beating a Hebrew, one of his brothers (מֵאֶחָיֽו; αδελφών των υίών Ισραηλ in LXX). (v. 11)

Similar cases are attested to in other Jewish literature. For example, 2 Baruch 77 conveys this concept:

And I, Baruch, went away from there and came to the people, and assembled them from the greatest to the smallest and said to them. Hear, O children of Israel, behold how many are left from the twelve tribes of Israel ... And because your brothers have transgressed the commandments of the Most High ... (vv. 1-3; see also 2 Bar 77:11-12)

Baruch identifies his fellow Israelites as brothers in 2 Baruch 77:4, and this denotes that Jews envisaged some fictive sibling relations with other Jews. The Testament of Moses 3:7 denotes the brothers as fellow Israelites who belong to the same family, namely, the house of Israel: 'And will say: "What shall we, with you, do, brothers? Has not this tribulation come upon the whole house of Israel?"' (see also T.Isaac 7:10).5

Israelites believed that they belonged to one family6 (the family of Abraham or the family of God),7 and also envisaged that they had a fictive sibling relationship with other Jews. However, Jews excluded Gentiles from this fictive brotherly bond. For instance, in Deuteronomy 17 it is written:

[Y]ou may indeed set over you a king whom the LORD your God will choose. One of your own community you may set as king over you; you are not permitted to put a foreigner ((נבָרְִי) over you, who is not your own brother (לֹא־אָחִ֖יךָ הֽוּא). (v. 5)

In this verse, a brother in the sense of a fellow Israelite is clearly distinct from a foreigner, who is not 'your own brother'. Deuteronomy 15 says:

[E]very creditor shall remit the claim that is held against a neighbor, not exacting it of a neighbor who is a brother, because the LORD's remission has been proclaimed. Of a foreigner you may exact it, but you must remit your claim on whatever any member of your community owes you. (vv. 2-3)

It is allowed to 'remit the claim' against a foreigner, but not against a brother. So, 'a brother' is distinct from a foreigner and may signify shared nationality or heritage which in the context a foreigner does not share.8 Deuteronomy 24:14 also juxtaposes a brother and an alien as distinct concepts: 'You shall not withhold the wages of poor and needy labourers, whether a brother or aliens who reside in your land in one of your towns' (see also Dt 23:20-21). In 1 Maccabees 2 it says:

And all said to their neighbours: 'If we all do as our brothers (οί αδελφοί ήμών) have done and refuse to fight with Gentiles for our lives and for our ordinances, they will quickly destroy us from the earth. (v. 40)

'Our brothers' refers to fellow Israelites, and we find also a clear distinction between brothers and Gentiles in this verse. These uses of 'brother', therefore, suggest that 'brother' refers to a kinsman in Israel's symbolic family based on shared ancestry or ethnicity. This usage is widespread in the OT and Jewish literature.9 Jews did not regard Gentiles as their brothers. So, metaphorical sibling terminology was used by

Jews in order to distinguish themselves from Gentiles who are not their brothers.

In ancient Jewish inscriptions, sibling terms do at times refer to biological brothers and sisters.10 However, figurative usage of sibling language is also found in some Jewish inscriptions. For example, in the Corpus inscriptionum judaicarum ii no. 1489 (=Alexandria Museum No. 20905; 1st century BC or AD), Theon, son of Paos is described as having 'loved my brothers and was a friend to all the citizens.' Here, 'brothers' may refer to the Israelite community (Horbury & Noy 1992:192, 195). This figurative sibling expression leads us to conclude that Jews in Alexandria described one another as brothers. Therefore, Jews were described as being brothers of fellow Jews in Jewish literature.

It should also be noted that Jews are not only 'described,' but also 'addressed' as brothers by fellow Jews. Within Jewish literature, In 2 Maccabees 1:1, Jews in Palestine address Jews in Egypt as 'brothers', and this indicates that sibling language connotes the same ethnic origin, not a regional meaning such as fellow countrymen (see also Tob 1:16). Sibling address forms in the vocative case are also found in 2 Baruch 80:1; 82:1; Liber antiquitatum Biblicarum 22:3; 26:5; Judith 7:29-30; 8:24; 14:1; Tobit 5:11-12, which evoke the vocative formulae 'brothers' and 'brother' in ancient Jewish letters.11 These vocative sibling addresses clearly denote that sibling language was used strictly within Jews.

In addition, the following features should also be considered. Each tribe in Israel also addresses members of other tribes as brothers as in Judges 1:

Judah said to his brother Simeon, 'come up with me into the territory allotted to me, that we may fight against the Canaanites; then I too will go with you into the territory allotted to you.' So Simeon went with him. (v. 3)12

Exceptionally, Edomites are collectively described as Israel's brother in Numbers 20:14 and Deuteronomy 2:4, 8 (cf. Dt 23:7). However, Edom and Israel share a historical and tribal background in that Edom and Jacob were brothers, and this may be the reason why Edomites are called Israel's brothers (Carmichael 1974:176). Some scholars also argue that the brotherly relationship between Israel and Edom reflects some historical treaty made between the two nations (Mayes 1979: 317). Accordingly, describing Edomites as Israel's brothers does not indicate that they took their place in the family of God. No other verse in the OT and Jewish literature suggests that Edomites were the brothers of Israel.13

Finally, were proselytes addressed as brother(s) by Jews? Proselytism to a certain extent denotes the universality of the Jewish religion. Converting to Judaism required three essential components: (1) 'practice of the Jewish laws'; (2) 'exclusive devotion to the god of the Jews'; and (3) 'integration into the Jewish community' (Cohen 1989:26). From the perspectives of outsiders, converting to Judaism could be understood as the act of becoming a Jew, but in the eyes of Jews, those Gentiles who converted to Judaism were not viewed as being Jewish. There is no evidence that 'proselytes achieved real equality with the native born' (Cohen 1989:29). Nonetheless, 'kinship is created not only through birth but also through the choice of the manner of life,' as Josephus states (Josephus Apionem. 2.28.210). 'The King [Cyrus the Persian King] has become a Jew' in Bel and the Dragon 28 may evidence that proselytism could provide the route for Gentiles to become Jews (Smith-Christopher 2002:136). Baba Qamma 88a also implies that proselytes were described as brothers of Jews, if they were subject to Mosaic commandments and if they lived together with Jews.14

In short, sibling language in Jewish literature highlights ethnic insider designation as a member of the family of Abraham. The notion of a brother often referred to the concept of a fictive kinship relationship in the symbolic world of Israel. Israelites' brotherhood distinguished them from Gentiles and foreigners, and assigned solidarity as a family member sharing a common blood relationship and ancestry. Therefore, sibling titles do not refer to a regional, but to an ethnic concept (e.g. 2 Macc 1:1), and Gentiles were not designated as brother(s) by Jews with the exception of proselytes.

Analysis of forms of address in ancient Jewish letters

General forms of address in ancient Jewish letters

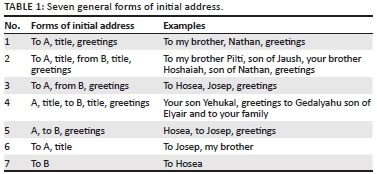

This section will explore forms of address in Jewish letters from the 6th century BC to 2nd century AD written in Aramaic, Hebrew and Greek. In the case of Aramaic letters, there are seven general forms of initial address (Table 1) (praescriptio) (cf. Fitzmyer 1974:211).

Forms of address were usually used in the opening addresses, but also in letter closings and sometimes in the letter bodies as in Greco-Roman correspondence. How, then, did Jewish letter writers address letter recipients? The most basic form was to use the names of the recipients, but the following forms were also used in many cases. Firstly, many letters indicated the family names of the recipients in the forms of 'son (or daughter) of the proper name (PN).' For example, the Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt (TAD) A3.6 Cowley 40 (Sachau Plate 13) line 5 writes: 'To my brother Pilti, son of Jaush, your brother Hoshaiah, son of Nathan.'15

Secondly, some letters introduce master and servant language to express the humbleness and politeness of the letter writers.16 In the Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt (TAD) A3.11 Letter from el-Hibeh (=Florence Inv. N. 11913), begins in the following way: 'To my lord Jashobiah your servant.' For other examples, in A3.9 Kraeling 13 Line 1, '[To my lord Islah, your servant] Shewa'; in the Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt (TAD) A3.8 Cowley 39 (Sachau Plate 13) Line 1, 'To my lady ((מראתי) Shalwah, your servant Hosea'; in Cowley 37 line 1 'To my lord Yedoniah, Manziah, Uriah and the army, your servant.'17

Thirdly, the origins and ethnic groups of recipients were addressed: in Cowley 5 line 2 'Koniya son of Zadok, an Aramaean of Syene, of the detachment of Warizath, to Mahseiah son of Yedoniah, an Aramaen of Syere'.18 Fourthly, letter writers addressed using official titles or the occupations of recipients: in Cowley 8 lines 1-2, 'Mahseiah son of Yedoniah, a Jew holding property in Yeb the fortress . to Mibtahiahm spinster, his daughter.'

Fifthly, kinship language was used to address letter recipients. Sometimes kinship language reflected the literal physical relationship,19 but kinship language was also employed figuratively. Father and son language was figuratively used to express the humbleness of the letter writers and to indicate the close relationship between letter writers and recipients. For example, Arad 21 (Catalogue No. 19), 'Your son Yehukal (hereby) sends greetings to (you) Gedalyahu [son of] Elyair and to your family'; and in Arad (Catalogue No. 22), 'Your son Gemar[yahu], as well as Nehemyahu, (hereby) sen(ds greetings to [you]).'

Sibling address forms were used to express the intimacy between letter writers and recipients.20 For example, in the Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt A3.6. Cowley 40 (Sachau Plate 13) line 1, the letter writer writes, 'To my brother Piltim your brother Hosaiah.' In a business letter named P. Princet. 73 (=CPJ III, 469 [3rd century AD]), Aphynchis (a Jew) designates Augaros21 as 'lord and brother'. Sibling language was also used to address the letter writers' father and mother.22 This denotes that sibling language was not always used in respect of equal relationships (contra Fitzmyer 1974:213).

Sibling language was also used for Jewish letter writers to address fellow Israelites,23 and sometimes referred to fellow Jews in certain Jewish letters. In a Hellenistic Jewish letter in 2 Baruch 78-86, Baruch addresses Jewish people as brothers:

Baruch, the son of Neriah, to the brothers who were carried away in captivity: Grace and peace be with you. I remember, my brothers, the love of him who created me. (2 Bar 76:2-3)

'The brothers . in captivity' refers to Baruch's fellow Jews.

In a Hebrew letter (P.Yadin 49; 1st century AD), a sibling term is mentioned in the body of the letter, and 'your brother' probably refers to fellow Israelites or to the community members (Yadin 1961:36-51; cf. 2 Macc 1:1):

From Shimon bar Koshiba to the men of Ein-Gedi To Masbala [and] to Yeho[n]atan son of Beyan. Greetings. Well off.

You are-eating and dr[i]nking from the goods of Beth-Israel and not giving a thought to your brothers from the ship there.24

Observations on forms of address in Jewish letters can be summarised as follows. Firstly, forms of address in Jewish letters do not demonstrate significant formal changes from the 6th century BC to 2nd century AD. Secondly, Jewish letter writers expressed specific relationships to their recipients, reciprocity, politeness and intimacy through forms of address. Thirdly, some significant differences are detected between Jewish letters and general Greco-Roman letters: (1) Jewish letter writers did not address non-Jewish recipients in sibling terms such as 'brothers'. This absence of the use of sibling terms to non-Jewish recipients is traced beyond region and time; and (2) in contrast to Jewish letters, Greco-Roman letter writers commonly used sibling language without reference to actual or symbolic familial relationships.25

Conversely, it seems that there were no issues when non-Jewish letter writers addressed their Jewish letter writers using sibling language. In a business letter named Papyrus grecs de la Bibliothèque Municipale de Gothembourg (P.Goth.) 114 (=CPJ III, 479 [3rd or 4th century AD]), Gerontios (non-Jew) addresses Josep, a Jewish banker, as 'my lord and brother'; this denotes that Gerontios speaks of Josep merely in Greco-Roman epistolary convention (in a widespread kinship form of address). In a letter preserved in Josephus, Antiquitates judaicae 13.2.2, Alexander Balas, son of Antiochus Epiphanes addresses Jonathan, a high priest as 'his brother': 'King Alexander to his brother Jonathan, Greetings' (cf. Josephus Ant. 13.4.9). These letters in Josephus' Antiquitates judaicae may reflect Greco-Roman official epistolographical customs, and this sibling language was used to reinforce intimacy between the letter writers and their recipients. In spite of this sibling language addressed to Jewish recipients by non-Jewish letter writers, Jewish letter writers rarely spoke of non-Jewish recipients as brothers in extant Jewish letters. In other words, Jewish letter writers rarely crossed ethnic boundaries by using sibling terms. What is the reason for this and how, then, did Jewish letter writers address their Gentile recipients?

Forms of address to non-Jewish recipients in ancient Jewish letters

Jewish letter writers use general forms of address to greet their letter recipients in conventional ways with the exception of the use of kinship terms. The basic form is to use the proper and family names of recipients. Hatres son of Sambathion (a Jew) addresses his recipients as 'Herakles, son of Psenobastis and Dios son of Petheus' (non-Jews) without using any other titles in Aegyptische Urkunden aus den Kõniglichen Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin (BGU) 166.26 Regional and ethnic origins were also used as forms of address: e.g., in the Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt (TAD) B.3.13 Kraeling 11, Anani (a Jew) addresses his recipients as 'Pakhnum, an Aramean of Syene.'

Jewish letter writers addressed non-Jewish recipients using their occupation or official position. For example, Cowley 2 line 2-3 reads, 'Hosea son of Hodaviah and Ahiab, son of Gemariah to Espemet, son of Peftonith the sailor ... of Hanani, the carpenter.' In the Griechische Papyri der Staats- und Universitàtsbibliothek Hamburg (P.Hamb.) 60, Pascheis (a Jew), a letter writer, addresses Justos (non-Jew) as 'strategos of the Hermopolite nome'. In the Papiri greci e latini (PSI) 883, Isakous (a Jew) speaks of Herakleides as 'strategos of the Arisinote nome'.27 In Rylands Papyri (P.Ryl.) 578, Judas, a son of Dositheos, calls Zopyrus (a non-Jew) as 'epimelete'. In the Aegyptische Urkunden aus den Kõniglichen Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin (BGU) 1140, Helenos, a Jew of Alexandria, addresses Gaius Turranius, a prefect of Alexandria as 'most powerful governor'.28

Master and servant language is also found in correspondence between Jewish letter writers and non-Jewish recipients: in the Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt (TAD) A4.7 (Cowley 30), 'To our lord Bigvai, governor of Judaea, your servants Yedoniah and his colleagues'.29 Horos, son of Sambathion (a Jew) addresses officers as 'lords' in Oxyrhynchus Papyri (P.Oxy.) 1472.

The relationship with the letter recipients' families was used in forms of address. In Eupolemus 31-33, Solomon addresses gentile kings as 'friend of my father': 'King Solomon to Vaphres King of Egypt and friend of my father, greetings!' in Chapter 31; 'King Solomon to Souron the King of Tyre and Sidon and Phoenica, friend of father, greetings!' in Chapter 33.

However, kinship language including sibling language was rarely used to express the relationship between Jewish letter writers and Gentile recipients. In the Greco-Roman world and the ancient Near East, sibling terms were widely used to address recipients who were not in biological blood relationships with the writer (Fitzmyer 1974:211-213). However, uses of sibling language toward non-Jewish recipients by Jewish letter writers are something of a rarity in ancient Jewish letters.

One exception is found in the diplomatic letters written by Jonathan, high priest to the Spartan king preserved in 1 Maccabees 12 and Josephus, Antiquitates judaicae, 13.266.30 The Gentile allies of Israel are addressed as brothers of the Jews, and so Aasgaard claims that it indicates 'usage which oversteps purely ethnic boundaries' (2004:113). However, it should be noted that the Spartans are addressed not only as brothers, but also as the family of Abraham in 1 Maccabees 12:11 and 21. Accordingly, 'brothers' also refers to members of the family of Abraham in this case, and the use of sibling language signals that sibling forms of address were used by Jews within the family of Abraham. As Doering observes, '[t]his fictive kinship between the Judaeans and Spartans is based on an earlier letter from the Spartan king Areios to the high priest Onias' (Doering 2012:142). Further, the authenticity of the letters has been disputed (Gruen 1998:258259), and as Bremmer (2010:56) notes, it is implausible that 'real diplomatic contacts' between Jews and Spartans took place during the Maccabean and Hasmonean era. These letters may reflect intra-disputes between the Hellenised Jews and those who strictly observed the Law in the Maccabean and Hasmonean period. Therefore, it is doubtful that, by those who strictly adhered to the Law, Gentiles were viewed as being in a fictive kinship relationship (cf. Klauck 2006:241). We find some parallels between Galatians 3-4 and the letters to the Spartans, and these parallels will be considered in the following part.

In brief, we can understand two clear points through these epistolary phenomena. Firstly, whilst Gentile recipients were addressed in various ways by Jewish letter writers, they were rarely designated as 'brothers' in early Jewish correspondence. Secondly, although sibling terms were used to denote a sense of intimacy and closeness, non-Jewish recipients were rarely designated as 'brother[s]' in ancient Jewish letters. Therefore, we conclude that Jewish letter writers must have refrained from designating their non-Jewish recipients as 'brother(s)', insofar as their recipients were not proselytes who observed the Law and sought to live like Jews. Thus, Jews in antiquity used sibling terms strictly within Jewish groups and those who were integrated into Jewish society as proselytes.

Ethnic aspects of sibling language in Paul's Letters

Paul figuratively uses 'brother(s)' approximately 112 times in the undisputed Pauline letters (Horrell 2001:299). Beutler argues that Paul used sibling language in four different figurative senses: (1) a neighbour; (2) a fellow kinsman; (3) a countryman; and (4) a fellow Christian. Beutler (2003:30) also claims that a fellow Christian is the prevailing sense of the sibling metaphors in Paul's letters. Yet, in Jewish writings and letters, sibling forms of address are linked to symbolic familial relationship, and this point is applied to Paul's uses of sibling language.

While, in Jewish letters, sibling language is frequently used in praescriptio, Paul does not use sibling language to address his letter recipients in the opening of his undisputed letters except for Philemon 1:1. By contrast, Paul often addresses his co-senders in sibling language (e.g. 1 Cor 1:2 [Sosthenes our brother]; 2 Cor 1:1 [Timothy our brother]; Gal 1:2 [all brothers who are with me]). As Fulton (2011:218) observes, 'it would seem that those named in the [Pauline] letter prescript as the senders of the letter are those who take responsibility for the contents of the letter,' and '[f]rom the viewpoint of the recipients of the letters, the co-senders, like Paul, were part of the team who founded the community' (Fulton 2011:174). If so, it seems that, through using sibling language to co-senders, Paul sought to show a close relationship between himself and those who were well known to the community. Sosthenes (1 Cor 1:2) was the official of the synagogue (Ac 18:18), and well known to the Corinthian saints. So perhaps, through using sibling language, Paul wanted to show that he had a partnership with the co-sender who was close to the letter recipients, and to imply that his message was endorsed by the co-senders. In other cases of the undisputed Pauline letters, Paul does not employ sibling language in letter openings. Perhaps, the absence of sibling language to address his recipients may reflect the quasi official feature of Paul's letters (Doering 2012:394-399).

However, we should note that Paul frequently uses sibling language in the vocative case to his letter recipients (most Gentile Christians) in the letter body and the letter closing (e.g. Rm 7:1, 4; 8:12; 10:1; 11:25; 12:1; 15:14, 30; 16:17; 1 Cor 1:10, 11, 26; 2:1; 3:1; 4:6; 7:24; 7:29; 10:1; 11:33; 12:1; 14:6, 20, 26, 39; 15:1, 50, 58; 16:15; 2 Cor 1:8; 8:1; 13:11; Gl 1:11; 3:15; 4:12, 28, 31; 5:11, 13; 6:1, 18; Phlp 3:1, 13; 4:1, 8, 21; 1 Th 1:4; 2:1, 9, 14, 17, 3:7; 4:1, 13; 5:1, 4, 12, 14, 25, Phlm 1:20). In Jewish letters, sibling language was frequently used in the body of the letter (e.g. 2 Bar 78:3; 79:1; 80:1; 82:1; P.Yadin 49). In Paul's letters, these epistolary sibling addresses in the vocative case clearly denote that Gentile Christians were designated as 'brother[s]' by Paul, the Jewish letter writer. If Paul addresses his Gentile letter recipients in sibling language, it was anomalous to Jewish epistolary conventions.

In 1 Corinthians 8:6, God is described as the believers' father and in 1 Corinthians 8:12-13, the believers are presented as brothers to one another:

[Y]et for us there is one God, the Father, from whom are all things and for whom we exist, and one Lord, Jesus Christ, through whom are all things and through whom we exist. (1 Cor 8:6)

and

Thus, sinning against your brother and wounding their conscience when it is weak, you sin against Christ. Therefore, if food is a cause of my brother's falling, I will never eat meat, lest I cause my brother to fall. (1 Cor 8:12-13)

It is implied in 1 Corinthians 10:1 that brothers are the offspring of 'our fathers' (Israel in Exodus): 'I want you to know, brothers that our fathers were all under the cloud, and all passed through the sea.'

Romans 9-11 and Romans 14-15 highly probably reflect intra-conflicts between Jewish and Gentile Christians in Rome (Moxnes 1980:78), and that 'the weak' in faith in Romans 14 refers to Jewish Christians who observed the Jewish cultic laws in the Roman church (Lampe 2003:72-73; Oakes 2009:76). A linguistic parallel of 'διακρίνω' in Romans 4:20 and 14:23 underpins the link between Romans 4 and Romans 14. 'Διακρίνω' is used twice (4:20; 14:23) in Romans, and this implies the conceptual link between verses 4 and 14. As Esler (2003:189) writes, in Romans 4, 'he [Paul] presents Abraham not as a figure who gathers in non-Judeans and excludes Judeans, but as one who incorporates both social categories.' Arguably, the concept of 'the descendants of Abraham' in Romans 4 is linked with the notion of 'brothers' in Romans 14. Paul repeatedly exhorts the Roman believers to accept 'the weak' in faith as their brothers (Rm 14:10, 15, 21), and in this context, it seems that Paul's sibling language in Romans 14 functions to reconstruct the Pauline church as one ethnic entity (cf. Sechrest 2009).

Likewise, it is possible to understand αδελφοί in Romans 8 in the same vein. In particular, αδελφοί in Romans 8:12 and 29 occurs in the context of kinship metaphors such as adoption in Romans 8:15, 23, inheritance (or joint inheritance) in 8:17, the firstborn son in Romans 8:29, sons and children in 8:14, 19 (υίός) and in Romans 8:16, 17, 21 (τέκνα), and άββά (Aramaic term addressed to God as Father) in 8:15. Romans 8 illustrates that the believers are adopted into the family of God and that they become joint heirs of Christ (Kim 2014:133-143). Joint inheritance was practiced between brothers in Greco-Roman society (Bannon 1997:13). We should note that the vocative αδελφοί in 8:12 is referenced to in the context of the family metaphors, particularly adoption and joint inheritance in Romans 8:14-17. Furthermore, in Romans 8:29, the Jewish and Gentile believers alike are Christ's brothers. So, 'πρωτότοκον έν πολλοίς άδελφοΐς' in 8:29 is a part of the kinship metaphors which are concerned with the reconstituted family of God. Thus, brothers in Romans 8:12 and 29 does not simply indicate friends or fellow workers, but members of the family of God.

Paul addresses Jews as 'my brothers' in Romans 9:

For I could wish that I myself were accursed and cut off from Christ for the sake of my brothers, my kindred according to the flesh (υπέρ των αδελφών μου των συγγενών μου κατά σάρκα). (v. 3)

This sibling relationship is defined 'according to the flesh (κατά σάρκα)'. In Romans 4:1, Abraham is presented as our father according to the flesh (κατά σάρκα), which denotes the ethnic origin of Jews. Thus, 'κατά σάρκα' in Romans 9:3 stresses the shared ethnicity and ancestry between Paul and the Jews, and it reveals that Paul follows Jewish usage of sibling language.

Allusions to Jewish usage of αδελφός appear in Galatians. In Galatians 3:7, men of faith are the sons of Abraham and they are also brothers in Galatians 3:14. In Galatians 4:28, Paul says, 'Now you yourself, brothers, are children of the promise, like Isaac' (ύμείς δέ, αδελφοί, κατά Ισαάκ επαγγελίας τέκνα έστέ). ύμείς in the emphatic position (you yourself) stresses that the Gentile believers in Galatia are the children of the promise, and that they belong to the family of God according to the promise. So, 'you, brothers' is implicitly linked with the ethnic and religious concept of sibling language. In Galatians 4:31, Paul again writes, 'So then, brothers, we are children, not of the slave but of the free woman', and this also connotes that the 'brothers' do not only refer to friends, neighbours or fellow believers. That is, 'brothers' are children and sons of God, and all the Gentile believers are members of the reconstituted family of God as brothers. We should note that Gentile believers are designated as members of the family of Abraham in Galatians 3 (cf. Rm 4), and this designation is clearly paralleled with the Spartans who were integrated into the family of Abraham as 'brothers' in 1 Maccabees 12:1 and Josephus Antiquitates judaicae 13.266. Therefore, the use of sibling language in Galatians 3-4, 1 Maccabees 12:1 and Josephus Antiquitates judaicae 13.266 signals that the fictive kinship language is used when referring to the same ethnic group.

It is, therefore, highly probable that Paul adopted the Jewish usage of sibling language. Nonetheless, Paul did not hesitate to designate his Gentile recipients as brothers. In other words, Paul's uses of sibling language signal that Paul thought that his non-Jewish recipients were true members of God's family. Paul's sibling terms suggest the Gentile believers' full membership of the familia Dei. Therefore, αδελφοί in Paul's letters denotes that the membership of the family of Abraham extends to Gentiles.

Conclusion

Ancient Jews did not address Gentiles as their brother(s), but Paul did entitle his letter recipients as 'brothers'. It should also be recognised that Paul's sibling language is related to its Jewish usage which is concerned with shared ethnicity. That is, Jewish letter writers rarely addressed their non-Jewish recipients as brothers. It is unlikely that Paul employed sibling language without being aware of its common Jewish usage. Therefore we can develop the conclusions of this article as follows:

1. Ascribing the title of brother to Gentile believers denotes that membership of the family of Abraham crossed ethnic boundaries. Scholars suggest that 'brothers' was gender-inclusive language, but few consider that it was Gentile-inclusive language. In other words, Paul's sibling language implies that Jewish and Gentile Christians alike are members of God's reconstituted family.

2. It is highly probable that Paul freely used sibling language when addressing his Gentile believers, because Paul understood the status of the Gentile believers as being that of the Jewish proselytes who were addressed by Jewish correspondents using sibling language. Consequently, designating Gentile believers as brothers is a key component of Paul's strategy to incorporate the Gentile believers into the family of Abraham.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationships which may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

References

Aasgaard, R., 2004, My beloved brothers and sisters: Christian siblingship in Paul, T&T Clark, London. [ Links ]

Arzt-Grabner, P., 2002, '''Brothers" and "'sisters" in documentary papyri and in Early Christianity', Revue Biblique 50, 185-204. [ Links ]

Bannon, C.J., 1997, The brothers of Romulus: Fraternal pietas in Roman law, literature, and society, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/9781400822454 [ Links ]

Beutler, J., 2003, s.v. 'αδελφός', in H. Balz & G. Schneider (eds.), Exegetical dictionary of the new testament, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, vol. 1, p. 30. [ Links ]

Bremmer, J.N., 2010, 'Spartans and Jews: Abrahamic Cousins?' in M. Goodman, G.H. van Kooten & J.T.A.G.M. van Ruiten (eds.), Abraham, the nations, and the Hagarites: Jewish, Christian, and Islamic perspectives on kinship with Abraham, pp. 47-59, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Carmichael, C.M., 1974, The laws of Deuteronomy, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY. [ Links ]

Cohen, S.J.D., 1989, 'Crossing the boundary and becoming a Jew', Harvard Theological Review 82, 13-33. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S001781600001600X [ Links ]

Cohen, S.J.D., 1999, The beginnings of Jewishness: Boundaries, varieties, uncertainties, University of California Press, Berkeley, CA. [ Links ]

Contini, R., 1995, 'Epistolary evidence of address phenomena in official and Biblical Aramaic', in Z. Zevit, S. Gitin & M. Sokoloff (eds.), Solving riddles and untying knots: Biblical, epigraphic, and Semitic studies in honor of Jonas C. Greenfield, pp. 57-67, Eisenbrauns, Winona Lake, IN. [ Links ]

Cowley, A., 1923, Aramaic Papyri of the fifth century BC, Clarendon, Oxford. [ Links ]

Dickey, E., 2004, 'Literal and extended use of kinship terms in documentary papyri', Mnemosyne 57, 131-176. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/156852504773399169 [ Links ]

Doering, L., 2012, Ancient Jewish letters and the beginnings of Christian epistolography, Mohr Siebeck, Tubingen. [ Links ]

Esler, P.F., 2003, Conflict and identity in Romans: The social setting of Paul's letters, Fortress, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Fitzmyer, J.A., 1974, 'Some notes on Aramaic epistolography', Journal of Biblical Literature 93, 201-225. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3263093 [ Links ]

Fulton, K., 2011, 'The Phenomenon of Co-Senders in Ancient Greek Letters and the Pauline Epistles', PhD thesis, The School of Divinity, History and Philosophy, University of Aberdeen. [ Links ]

Gruen, E., 1998, Heritage and Hellenism: The reinvention of Jewish tradition, University of California Press, Berkeley, CA. [ Links ]

Harland, P.A., 2005, 'Familial dimensions of group identity: "Brothers" (ΑΔΕΛΦΟΙ) in Greek East', Journal of Biblical Literature 124, 491-513. [ Links ]

Horbury, W. & Noy, D., 1992, Jewish inscriptions of Graeco-Roman Egypt: With an index of the Jewish inscriptions of Egypt and Cyrenaica, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Horrell, D.G., 2001, 'From αδελφοί to οίκος θεοΰ: Social transformation in Pauline Christianity', Journal of Biblical Literature 120, 293-311. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3268296 [ Links ]

Kim, K.S., 2014, 'Another look at adoption in Rom 8:15 in light of Roman social practices and legal rules', Biblical Theology Bulletin 43, 133-143. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146107914540488 [ Links ]

Klauck, H-J., 2006, Ancient letters and the New Testament: A guide to context and exegesis, Baylor University Press, Waco, TX. [ Links ]

Lampe, P., 2003, Christians at Rome in the first two centuries: From Paul to Valentinus, T&T Clark, London. [ Links ]

Lassen, E.M., 1992, 'Family as metaphor: Family images at the time of the Old Testament and early Judaism', Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament 6, 247-262. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09018329208584995 [ Links ]

Levenson, J.D., 2006, Resurrection and the restoration of Israel: The ultimate victory of the god of life, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT. [ Links ]

Lindenberger, J.M., 2003, Ancient Aramaic and Hebrew letters, Scholars, Atlanta, GA. [ Links ]

Malherbe, A., 1995, 'God's new family in Thessalonica', in L.M. White & O.L. Yarbrough (eds.), The social world of the first Christians: Essays in Honor of Wayne A. Meeks, pp. 116-125, Fortress, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Mayes, A.D.H., 1979, Deuteronomy, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Meeks, W.A., 1983, The first urban Christians: The social world of the Apostle Paul, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT. [ Links ]

Montevecchi, O., 1957, 'Dal Paganesimo al Cristianesimo: aspetti dell' evoluzione della lingua greca nei papiri dell'Egitto', Aegyptus 37, 41-59. [ Links ]

Moxnes, H., 1980, Theology in conflict: Studies in Paul's understanding of God in Romans, Brill, Leiden. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/9789004266643 [ Links ]

Neusner, J., 1989, Judaism and its social metaphors: Israel in the history of Jewish thought, Cambridge University Press Cambridge. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511557378 [ Links ]

Oakes, P., 2009, Reading Romans in Pompeii: Paul's letter at ground level, SPCK, London. [ Links ]

Perlitt, L., 1994, '"Ein einzig Volk von Brüdern" Zur deuteronomischen Herkunft der biblischen Bezeichnung "Bruder"', in L. Perlitt (Hrsg.), Deuteronomium-Studien, pp. 50-73, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen. [ Links ]

Schàfer, K., 1989, Gemeinde als 'Bruderschaft': Ein Beitrag zum Kirchenverstándnis des Paulus, Peter Lang, Frankfurt. [ Links ]

Schelkle, K.H., 1954, s.v. 'Bruder', in T. Klauser (ed.), Reallexikon für Antike und Christentum, Hiersemann, Stuttgart, vol. 3, pp. 631-640. [ Links ]

Sechrest, L.L., 2009, A former Jew: Paul and the dialectics of race, T&T Clark, London. [ Links ]

Smith, M.S., 2001, The origins of biblical monotheism: Israel's polytheistic background and the Ugaritic texts, Oxford University Press, Oxford. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/019513480X.001.0001 [ Links ]

Smith-Christopher, D.L., 2002, 'Between Ezra and Isaiah: Exclusion, transformation, and inclusion of the "foreigner" in post-exilic biblical theology', in M.G. Brett (ed.), Ethnicity and the Bible, pp. 117-142, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Taatz, I., 1991, Frühjüdische Briefe: Die paulinischen Briefe im Rahmen der offiziellen religiòsen Briefe des Frühjudentums, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Góttingen. [ Links ]

Trebilco, P., 2012, Self-Designation and group identity in the New Testament, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Van Houten, C., 1991, The Alien in Israelite Law, Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield. [ Links ]

Yadin, Y., 1961, 'Expedition D', Israel Exploration Journal 11, 36-51. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Kyu Seop Kim

402, Wongok-ro 32, Danwon-goo, Ansan-shi

Kyounggi-do, South Korea, 425-846

johnstott77@gmail.com

Received: 13 Nov. 2014

Accepted: 14 Mar. 2015

Published: 17 June 2015

1.Malherbe writes, 'Pagans as well as Jews described members of various conventicles and associations as brothers, and we do not know what Paul's source was for his usage' (1995:122). On the other hand, P.A. Harland highlights fictive kinship language in cultic, occupation, ethnic, gymnastic and civic associations in the Greco-Roman world (2005:491-513). Aasgaard also focuses on the Greco-Roman and sociological implications of Paul's sibling language (2004; cf. Arzt-Grabner 2002:202).

2.In Greco-Roman papyri, sibling terms were also frequently employed. In this vein, Montevecci argues that αδελφοί was widely used for a variety of applications denoting physical brothers as well as honourable colleagues in the Hellenistic world, particularly in the Eastern world (Montevecchi 1957:57-58; cf. Schelkle 1954:635).

3.Doering (2012); Taatz (1991). Irene Taatz investigates the purposes of ancient Jewish letters, and analyses Semitic epistolary formulae in Jewish letters. Taatz does not agree with a scholarly tendency to consider Paul's letters in terms of Greco-Roman private letters. Taatz's work has some pertinent points to this study; however, she does not explore ethnic dimensions of sibling language in light of Jewish epistolary tradition.

4.For example, 1 Enoch 100:1; 4 Ezra 7:103; Testament of Simeon 2:7, 13; 4:2; Testament of Levi 6:5; Testament of Judah 3:10; 4:1; 7:1, 6, 11; 9:1; 13:3; 25:1; Testamet of Issachar 1:3; 3:1; Testamet of Zebulon 1:5; 3:2-3; Testament of Joseph 1:1, 2; 17:2, 3; Testament of Benjamin 2:1, 3; 3:3, 6; 5:4; 7:4, 5; 8:1; Testament of Job 1:6; 51:2; 53:1; Testament of Isaiah 3:15; 6:6; Testament of Adam 3:5; Joseph and Aseneth 22:4; 23:4-5, 28:2; Letter of Aristeas 1:7; Jubilees 4:4, 16, 20, 27; 13:1; 24:3, 5; 25:1, 6; Liber antiquitatum Biblicarum 8:10; 12:1; 32:1; 37:1, 4; 44:5; 59:3; 4 Maccabees 8:3, 5, 19; 10:2; 11:20; 12:2-3, 17.

5.For other uses of 'brother' as a fellow-Israelite, see Liber antiquitatum Biblicarum 22:3b; 4 Ezra 12:12; 2 Baruch 33:2; 77:5, 12, 17; 78:2, 3, 5; 80:4; 82:2; 84:8; 85:7; Liber antiquitatum Biblicarum 22:6; 27:12, 14; 46:1, 2; 56:1; Judith 8:14; 8:22; Tobit 1:3, 16; 2:2; 4:12-13; 5:6; 5:13-14; 6:7, 11, 14, 16; 7:3-4, 9; 7:11; 9:2; 10:13; 11:8; 14:4; 14:7; 1 Maccabees 2:41; 2:65; 5:13; 5:16; 5:25; 6:22; 2 Maccabees 1:1; 12:6; 3 Maccabees 4:12; Sirach 40:24; Rule of the Community (1 QS) 4.8-10; The Damascus Document (CD-A) Col. VI 18-Col. VII 4; Temple Scroll (11Q19) Col. LVI, 12-15; Philo,De virtutibus. 82 and et cetera. See also usages of 'brother(s)' in War Scroll (1QM) XIII 1; XV 4, 7; 4Q163 Frags. 4-6 Col. I 16; 4Q197 Frag 4 Col. I 12, 16; Frag 4 Col. III 4; 4Q 198 Frag I, 6; Temple Scroll (11Q19) Col. LVI 14-15; The Damascus Document (CD-A) Col. VIII 5-6; 4Q372 Frag. 1 19-20; 6Q15 Frag. 4 1; Psalms Scroll (11Q5) Col. XIX 17; Temple Scroll (11Q19) Col. LVIII 14; 11Q19 Col. LXI 10; 11Q19 Col. LXII 4; 11Q19 Col. LXIV 12-15. For vocative uses of 'brothers' in an ethnic sense, see 2 Baruch 80:1; 82:1; Liber antiquitatum Biblicarum 22:3; 26:5; Judith 7:29-30; 8:24; 14:1; Tobit 5:11-12.

6.In a figurative sense, Israel was recognised as one family and one social entity by Jews. Amos 5:25 states that Israel is a family (בַּיתִ; οίκος). Israel was designated as a son of God (Ex 4:22; Jr 31:9, 20; Hs 11:1; cf. Ex 6:6-8), and the king of Israel was also designated as a son of God as the representative of the people (2 Sm 7:14; Ps 2:7). Israel as a family is distinct from all peoples on the earth: 'You only have I known of all the families (מִשְׁפּחְ֣וֹת) of the earth' (Am 3:2a). Yahweh was also viewed as the father of Davidic kings (Ps 89:26). Jon D. Levenson also notes, 'to be a Jew means to be a member of a natural family, the people Israel, the descendants of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob' (Levenson 2006:22; cf. Neusner 1989:112-144; Lassen 1992). Smith argues that the concept of the divine family in the OT is rooted in West Semitic societal concepts (2001:54-66). However, a similar idea concerning the ethnic extended family also existed in Ancient Greece. For example, Aristotle says that if some people are offspring of a common ancestor, it means that they are in a sort of fraternal relationship, in Aristotle, Ethica Nicomachea 8.12.4. So, the notion of the ethnic extended family was arguably widespread in the Mediterranean world.

7.For example, in Pirke Aboth II, 2, 19, 23, the disciples of Abraham are the heirs and Israel are the sons of God.

8.L. Perlitt also points out this contrast in Deuteronomy 15:2-3 (1994:35). As for Leviticus 25:47-51. Van Houten also notes, 'it is made clear that the alien is a non-Israelite. "One of your brothers" is set over against the temporary resident and the alien. This is exclusive language, and draws the line between insiders and outsiders quite distinctly' (Van Houten 1991:129).

9.For example, Leviticus 19:17; 25:25, 35, 39; 25:46 (see the expression, 'your brother, the sons of Israel'); Numbers 16:10; 18:2; 18:6; 20:3; 25:6; Deuteronomy 1:16, 28; 3:18, 20; 15:8-12; 17:20; 18:15, 18; 19:18-19; 20:8; 22:1-4; 24:7; Nehemiah 5:1; 8:10; Esther 10:3; Psalms 22:23; 133:1; Isaiah 66:20; Jeremiah 7:15; 29:16; 31:34; 34:9, 14, 17; Ezekiel 33:30; 47:14; Micah 5:2; 7:2; Zechariah 7:9, et cetera.

10.For instance, see Corpus inscriptionum judaicarum ii. 1507 (late 1st century BC - early 1st century AD); 1516 (5th century AD); 1488 (34 or 33 BC) (cf. Horbury & Noy 1992:154, 160, 191). In Corpus inscriptionum judaicarum i2 no. 718a, 'brothers' refers to family members or the community members.

11.'My brothers' is used in a vocative form in the body of Baruch's letter (2 Bar 78:3; 79:1; 80:1; 82:1).

12.Deuteronomy 10:9 also mentions the Levites are the brothers of Israel. For the similar cases, see Numbers 32:6; Deuteronomy 33:24; Joshua 1:14-15; 22:3-4; 22:7-8; Judges 1:3; 1:17.

13.Rather, the destiny of Edom differs from Israel's in Jeremiah 49:10; Amos 1:10-14; Malachi 1:10-14.

14.Cohen maintains, ‘What makes Jews distinctive, and consequently what makes "judaizers"distinctive, is the observance of the ancestral laws of the Jews. Therefore if you see someone observing Jewish rituals, you might reasonably conclude that the person is Jewish’ (1999:59).

15.Also see Cowley 5 line 2; Cowley 29 line 1; Cowley 35 line 3; Cowley 43 line 2; Cowley 44 line 2; Cowley 49 line 1.

16.Master and servant language was widespread in the ancient Near East. For example, the Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt (TAD) A6.1 Cowley 17 (Sachau Plate 5) line 1: 'To Our lord Arsames, your servants Achaemenes and his colleagues, Bagadana and his colleagues, and the scribes of the province'; Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt (TAD) A5.3 Cowley 70 (Corpus inscriptionum semiticarumII/1 144) line 1, 'To my lord Mithravahisht, your servant Pahim.'

17.In the Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt (TAD) A 4.3 Cowley 38:1-2, Manziah, one of the five leaders of the Jewish community, addresses Jedaniah and Uriah as 'my lords', even though they were his colleagues which shows Manziah's politeness to them in the situation where he needs their help.

18.See also Cowley 10, lines 2-3; Cowley 14, line 3; Cowley 15 line 2.

19.For a biological daughter, see Cowley 8 line 2; Cowley 13 line 2; Cowley 20 line 3; Cowley 34 line 5. For biological brother, see Corpus papyrorum judaicorum (CPJ) 42, 127a, 135, 142, 144, 201, 240, 431, 441, 481a, 482, 486a, 493, 518c, 1488, 1489, 1507, 1516. These papyri were written from the Ptolemaic period to the Byzantine period. In Corpus papyrorum judaicorum (CPJ) 436, (2nd century AD), Aline, a non-Jew, addresses her husband, Apollonios (non-Jew) as her brother, and it may imply a brother-sister marriage.

20.The Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt (TAD) A3.3 Padua I provides an interesting example where the father addresses himself to his son: '[Greetings] to the [Temple] of YHW in Elephantine. To my son Shelomam [frjom your brother Osea'. Cf. Lindenberger (2003:36-37). See also Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt (TAD) A3.4 Padua 2 lines 1 and 8: 'To [my] mother Jehoishma, your son Shallum'; 'To my brother Shelomam, son of Osea, your brother Osea son of Pete [...].' Cf. in Cowley 41 line 1, 'To my brothers Zeho and his sons, your brother...'; in Cowley 42 line 15, 'To my brother ... us son of Haggai, your brother Hosea'; in Cowley 56 line 4, 'To my brother son of Gadol, your brother Yislah son of Nathan'; and in Arad 16 (597 BC) lines 1-3, 'Your brother Hananyahu (hereby) sends greetings to (you) Elyashib and to your household. I bless you to YHWH.'

21.Line 16 implies that Auagaros (the letter recipient) belonged to 'the house of Eissak' (Jewish name), and so Augaros must be a Jew. Aphynchis, the letter-writer, is a Jew, because he also prayed in the name of the Lord God in the letter opening: ('First of all, I pray for your security before the Lord God') in line 3-4. Cf. Tcherikover Corpus papyrorum judaicorum (CPJ) III 30.

22.Contini specifically explores this aspect in ancient Aramaic letters (1995:60-64).

23.It was common in the Ancient Near East to address recipients who were not biological siblings as 'brother(s)'. For instance, in the Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt (TAD) A2.1 bresciani-Kamil 4 (non-Jewish letter), peers call themselves brothers and sisters. For the examples of Elephatine papyri, see Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt (TAD) A 2.2:1; A 2.3:1; A 2.4:5; A 2.5:1; A 2.6:1; A 2.7:5; A 3.3:14; A 3.3:1, 5; A 3.8:1, 15; A 3.10:1, 9; A 4.1:1, 10. Cowley 21 line 1, 11. In A 3.8 Cowley 42:1, 15, Hosea (a Jew) speaks of Haggus (a Jew) as 'brother'.

24.For examples of where writers address fellow Jews as brothers in Rabbinic letters, see Sanhedrin 2:6; Avodah Zarah 18a, 27b.

25.E. Dickey argues that the usage of sibling terms in Greco-Roman letters does not necessarily imply intimacy or affection between the letter writers and the letter recipients, and that sometimes 'brother' was used for those whom the letter writer did not know (Dickey 2004:155-156; cf. Harland 2005:491-513).

26.For similar examples, see Aegyptische Urkunden aus den Königlichen Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin (BGU) 1151; 1102; 1129; Selected Papyri from the Archives of Zenon (P.Edg.) 13, 84; Cairo Zenon Papyri (PCZ) 59377; Michigan Papyri (P.Mich. Zen.) 55. Cowley 7 lines 2-3 also states that, 'Malchiah son of Joshibiah of Nabukudurri, to Phrataphernes son of Artaphernes'.

27.In Papyri from Magdola (P.Magd.) 3, three Jewish farmers address Ptolemy as king using his name.

28.For examples of where the official titles are modified alongside adjective, 'most powerful,' see Oxyrhynchus Papyri (P.Oxy) 353, Aegyptische Urkunden aus den Kõniglichen Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin (BGU) 1068, Greek Papyri in the British Museum (P.Lond.) III, P. 25, no. 1119a.

29.For similar examples, see the Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt (TAD) A4.10 (Cowley 33); and Cowley 70 line 1: 'To my lord Mithravahisht, your servant Pahim.' In Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt (TAD) A4.8 (Cowley 31), Jedaniah, a Jewish leader, addresses Bagarahya (non-Jewish governor of Judah) as 'Lord' and humbles himself as 'servant'.

30.For example, 1 Maccabees 12:6-7; 12:11-21. For the similar cases, see Josephus Antiquitates judaicae 13.166.