Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

HTS Theological Studies

On-line version ISSN 2072-8050

Print version ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.71 n.3 Pretoria 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v71i3.2761

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

The value of traditional African religious music into liturgy: Lobethal Congregation

Morakeng E.K. Lebaka

Department of Old Testament Studies, Faculty of Theology, University of Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study was to discover whether the integration of traditional African religious music into Evangelical Lutheran liturgical church services, could effect a change in member attendance and/or participation. To achieve this, the study employed direct observation, video recordings and informal interviews. In addition, church records of attendance during Holy Communion once a month between 2008 and 2013 were accessed. The study was done at the Evangelical Lutheran Church of the Lobethal Congregation (Arkona Parish, Northern Diocese, Sekhukhune District, Limpopo Province, South Africa). It was demonstrated that church attendance increased dramatically after traditional African religious music was introduced into the Evangelical Lutheran liturgical services in 2011. Observations and video recordings showed that drums, rattles, horns and whistles were used. Handclapping was seen to act almost as a metronome, which steadily maintained the tempo. It was concluded that introducing traditional African religious music into Evangelical Lutheran liturgical church services has increased attendance and participation of church members. Therefore, the introduction of African religious music could be considered for other Evangelical Lutheran congregations in Africa.

Introduction

Singing is linked to religious experience and expression. In both the Lutheran and Reformed traditions - to name but two - music plays an important part in worship. Luther accepted music as part of the true church, and as an expression of faith itself.1 Calvin referred to music as 'sung prayers' (Calvin 1960:894). It is clear that there are fundamental links between singing and life. In fact, singing is (a mode of) life - an expression of the existential dimension of life. This fundamental link entails, inter alia, the following:

- singing as ritual (liturgical dimension)

- singing as worship and confession

- singing as spirituality (and therefore shaping of God-images)

- singing as hermeneutics, that is, as a mode of giving meaning.

However, the intention of African rhythm is not (as the word 'discontinuity' may suggest) to 'disrupt' the flow of the music; rather it means that the emphasis is not necessarily on melodious coherence, but on the impetus for life that rhythm can provide. In African spirituality singing is all about bringing people back to the right rhythms of life. Music and dance provide an opportunity for people to participate emotionally and physically in prayer and worship. There is a growing body of evidence to support this view; for example, Maboee (1982:131) observes that 'traditionally, when Africans worship, they sing and dance together. They have a tendency to become emotionally or spiritually involved in the service'. It is noteworthy in this context that music is an intrinsic part of everyday life, as well as in religion. One could even argue that music in all its forms is the central theme, which runs through all aspects of life, including the church. Along similar lines, it is worthwhile to mention here Kubik's (2001:199) view on music and movement; according to him, music in Africa is almost naturally associated with movement and action, such as playing percussion instruments, clapping of hands or dancing.

From a cultural point of view, African people do not always feel comfortable in a controlled and/or solemn church environment where emotions are not expressed freely. In Independent Churches, singing is always accompanied by the clapping of hands, and the whole church service is turned into a more colourful experience for the members of the congregation. Mainstream churches, where traditional music is seldom used, may lose members to Independent Churches, because of passive participation. In consonance with the aforementioned observation, Chernoff (1979:61) writes that music in the African context is experienced physically as it anticipates movement in the form of dance. In the same vein, Bosch (2005:420-432; 447-457) surmises, quite realistically, that no single gospel exactly fits one situation. He emphasises that the gospel always needs to be contextualised differently. This study argues that traditional African religious music is indispensable in mission work as it proclaims the gospel within the missionary context.

Research literature

Theoretical background: Theological perspectives on music and mission

Commentators such as Lilje (1992), Mugambi (1989), Friesen (1982), Schrag (1989), Hunt (1987) and others2 have raised arguments about models of music and mission.3 Schrag (1989:312) argues that the missionary has to become 'bimusical'. He suggests that a person is bimusical, insofar as he or she is able to differentiate between two musical systems and is able to participate creatively within them. Accordingly, this concept is justified musicologically, as all cultures know music, even though it is 'not a universal language' (Schrag 1989:313).4 In his view, it is also justified anthropologically because of the strong links between culture and music (Schrag 1989:313-314), and biblically, as 'wherever God's people are, there is to be music' (Schrag 1989:315). To prove his biblical justification of the necessity of employing new music in mission, Schrag (1989:315) appropriately quotes Genesis 1:27, Romans 1:20, Psalm 19:1, Ephesians 15:18-19 and 1 Corinthians 14:15. In particular, he argues that when a new church is born, God wants to hear new music (Ps 49 and 98), and the missionary must encourage that. Although naturally one does not find any hints in terms of a 'new church' in the given Psalms, the emphasis on new music in mission has to be acknowledged. Schrag (1989:315) stresses that music is an important key to understanding a culture that enables the missionary to communicate the gospel more accurately and sensitively.

Attesting to Schrag's concept relating to being 'bimusical', according to Hunt's (1987:33) definition, it includes worshipping in context; memorising of life activities associated with certain melodies; considering the cultural framework of music; the changes occurring through introduction of foreign musical systems; and discovering 'the conceptual process in which music is heard' (Hunt 1987:144151). Hunt (1987:33) argues that, our choice, if we are to be effective missionaries, is not whether we will use music. Our choice is how we will use it: effectively, efficiently, spiritually, or slovenly and carelessly. This practical approach to the missionary-functional quality of music, as done by Hunt, has doubtlessly to be appreciated.

Protestant theologians such as Friesen (1982), Nelson (1999) and Kraft (1980) often focus on the subject from the ethno-musicologist's point of view; for example, Friesen (1982:83-96) expanded a methodology in the development of indigenous hymnody. In Friesen's (1982:92-94) discussion of the development of contextualised music, he distinguishes several basic 'missiological principles', linked to the development of contextualised music for an Africanised Lutheran liturgy. Friesen (1982:85) describes his methodology as consisting of two parts: the 'ethno-musicological' (the study of forms and functions of song types, instruments, singers, instrumentalists and technical characteristics of any culture) and the 'psycho-ethno-musicological' (the study of the person's relationship to the native music). He argues that ultimately, everything in every culture must be evaluated in the light of both biblical principles and ethno-theology of the society. In his article Crossing the music threshold, Nelson (1999:152:155) examines how culturally attuned music fosters communion with God. Nelson (1999:152-155), for example, examines the role of 'ethno-musicological' research in the mission context, herein stressing the importance of the bonds between music and culture, and arguing that God can and will use whatever we have for his kingdom and service. Kraft (1980:211-236) promotes his 'dynamic equivalent model' to describe the position and task of 'The Church in Culture', claiming that his model is the best approach to enable the church to convey the message of God most faithfully in its surrounding culture (Kraft 1980:230); included in this culture is music.

The aforementioned arguments are wholly convincing, simply because there is no music or religion, which is superior to the other. The point I want to make, and the first conclusion to draw from the aforementioned arguments, is that it would be convenient if not entirely accurate to describe the approach (of the models of the three protestant theologians) to musical meaning as the focus on the development of music and mission. Friesen's point of view stated earlier links closely to what Darby (1999:66) terms 'African spirituality'. Darby gives the example of the mode of worship whereby worshippers are afforded the opportunity to worship God the way they like. Some mainstream church denominations in Africa have incorporated this mode of worship into their liturgical church services whereby music, rhythm and ceremonies are intrinsically African in nature. It is therefore not surprising that Nelson (1999:152-155) provides convincing evidence of the relationship between music and culture.

Aims and objectives

The general objective of this study is to investigate the impact of the integration of traditional African religious music into Evangelical Lutheran liturgical church services. The specific objectives are to find out:

- whether the Evangelical Lutheran hymnal has worthy poetic hymns relevant to the traditional African background

- whether the integration of traditional African religious music into Evangelical Lutheran liturgical church services respects the Lutheran tradition.

Research methodology

The present study is an exploratory observation. This study is based on interviews and observations. The informants came from the Evangelical Lutheran Church of the Lobethal Congregation (Arkona Parish, Northern Diocese, Sekhukhune District, Limpopo Province, South Africa). A total number of 16 informal interviews were also conducted to generate qualitative data. The interviewees were purposively selected through the assistance of informants. The first data set dates from April 2008 when video recordings were made; the main study began in 2009. Since then, there have been additional studies with this congregation both during liturgical church services and later during the week for informal interviews.

For the purpose of this study, four Evangelical Lutheran liturgical church services were recorded and studied. The church pastor, seven congregants, choir conductor, two choir members, three of those playing instruments, as well as two church elders, were informally interviewed around three research questions:

- Does the integration of traditional African religious music into Evangelical Lutheran liturgical church services make a significant difference in perceptions of attendance and participation?

- Does the Evangelical Lutheran hymnal have worthy poetic hymns relevant to the traditional African background?

- Does the integration of traditional African religious music into Evangelical Lutheran liturgical church services respect the Lutheran tradition?

Observational information and field notes were gathered during Evangelical Lutheran liturgical church services. The data were gathered in Sepedi, the home language of the interviewees and the researcher. The richness and quality of data were enhanced by congregants' involvement. The interview transcripts were analysed using content analysis.

Results

Findings are presented in line with the study objectives for clarity. Observations and video recordings confirmed active participation in liturgical church services from 2011. Not only were traditional instruments like drums, rattles and whistles used, but also song and movements were also traditionally African; for example, handclapping played a prominent role. An interesting observation on the vital, if not central, role of handclapping observed in liturgical church services should be mentioned. From this study, it appeared that handclapping helped to maintain the tempo as the Lobethal Congregation gradually and habitually slowed the tempo of hymns during the course of the performance. It was noticeable that when handclapping was incorporated, the tempo was regularised, thereby producing a metronome effect.

Table 1 shows how attendance grew after traditional African instruments and music were introduced in liturgy. The data were obtained from attendance at Holy Communion in the Lobethal Lutheran Church as the numbers of congregants at the Holy Communion (which takes place 12 times a year) are recorded in church records. During the Holy Communion, all participants put their names on envelopes with offerings of money, as this has to be recorded for financial transparency. The numbers are always higher during Easter and Christmas because most people are at home for these religious holidays; the results for these two months have been highlighted (Table 1).

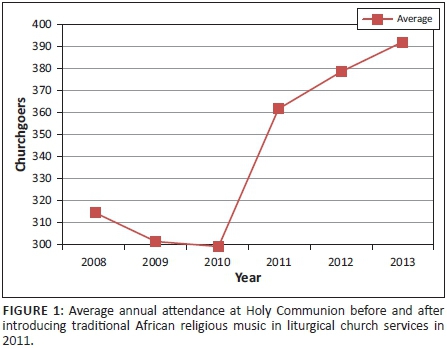

The monthly attendance figures shown in Table 1 were averaged in order to show the increasing number in terms of annual attendance (Figure 1).

It is clear from Table 1 and Figure 1 that the introduction of traditional African religious music into the liturgical church services had a positive effect on church attendance. It can also be deduced that people did not only attend these services, but made contributions to the church, as each member had put a donation in an envelope at Holy Communion - every month.

Informal interviews with participants (such as the choir conductor, two choir members, as well as three of those playing instruments) revealed that almost none of the singers or congregants in the Lobethal Congregation received formal training either in music education or music composition. It is noticeable that the creative music-making takes place during a process of interaction between congregants' musical experience and competence, their cultural practice, their traditional instruments, and the instructions.

With regard to the Lutheran hymnal, the enquiry revealed that it has worthy poetic hymns, but in most cases, the emotions are suppressed and restrained. Even though the music is well arranged, the cultural blend is lacking.5 This shows that the missionaries did not consider the traditional African religious background. It has emerged from this study that the question of culture is instrumental in liturgical church services, whereas its consideration has been generally neglected in the past. Dierks (1986:37) endorses this observation by stating that early missionaries were not in the position to compile indigenous hymnbooks, catechisms or liturgical formulas. Dierks supports his position by noting that the important and positive role music and liturgy could play regarding indigenisation, is not considered.

Other scholars clearly feel the same way. Amalorpavadass (1971:11), for example, states that a truly Indian liturgy has been shaped through the implementation of Indian instead of Western music. He suggests that, considering the cultural impact on liturgy (including its music), the future of worship and its music should be written by both the church and society. On a similar note, Friesen (1982:92-94) believes that continuity of culture is vital to a smooth transition and thus an indigenous development of Christianity. In his view, an analysis of the indigenous music system is necessary in order to develop an intelligible, theological and cultural hymnody for the church.

With reference to the cultural dimensions of liturgy, the study has shown that the connection between culture and religion results in as many liturgical forms as there are cultural concepts (Chupungco 1994:153). Thus, liturgy and music are instrumental in expressing one's culture, particularly in the mission context. It was also interesting to learn from one of the church elders of the Lobethal Congregation (during the course of an interview on 10 July 2011) that if the congregants are afforded the opportunity during the church service to express their own feelings in praising God, when it comes to Sunday offering, they offer more because they are happy.

When participants were asked whether the integration of traditional African religious music into Evangelical Lutheran liturgical church services respects the Lutheran tradition, all agreed. They felt this approach produces a liturgical form, which respects both the Lutheran tradition (with its emphasis on theological teaching) and African culture (with its deep affinity to music and rhythm). It seems obvious from the results that such an African - Lutheran liturgy, faithful to both Lutheran theology and African culture, has the potential to increase participation and attendance in Evangelical Lutheran liturgical church services.

The study has revealed that the introduction of traditional African religious music into Evangelical Lutheran liturgical church services has not compromised6 the essence of Christian worship. It has rather encouraged maximum and unimpeded participation in worship by members. Similar to my argument, Lieberknecht (1994:281;283) rightly claims that singing in particular helps the congregation of God to recognise itself as church, so that it can establish its own identity through music and appears attractive to outsiders. Nketia (1974:15) adds that apparently the fact that drums and other percussion instruments were used in the Ethiopian church, which had been established in the 4th century AD, did not affect the evangelistic prejudices. Noteworthy is the fact that even the mission churches, such as the Anglican, Roman Catholic and Dutch Reformed Churches, have incorporated similar music into worship.7 Since the introduction of such musical forms, the massive movement of their members to Independent Churches (because of passive participation) seems to have abated.

The findings of the analysis not only confirmed the positive impact of traditional African religious music on Evangelical Lutheran liturgical church services, they further substantiated the biblical passage which states that 'Praise him with drums and dancing' (Ps 150:4).

Discussion

Results of this study are similar to results obtained by Lutheran Bishop Lilje (1992:110-111), for instance, who recognises the importance of liturgy for the mission work of the Lutheran church (especially in the South African context). He argues that we need to develop an alternative liturgical order for our services that caters to our mission work, and a liturgy that expresses the joy and liberation of the gospel; it should be appropriate for the South African context and should reflect our Lutheran theology.

After reviewing the results yielded thus far, it is clear that traditional African religious music in general has a great impact on Evangelical Lutheran liturgical church services. It is noticeable that whilst traditional African religious music is carried out with the help of traditional musical instruments (e.g. meropa [drums], dinaka [whistles], dithlwathlwadi [leg rattles] and mekgolokwane [ululation]), liturgy enables the congregants to encounter God within the context of a worship service.

The results of this study also support Scott's (2000:9) assertion of a relationship between music and culture, because using cultural music increased participation in worship. He argues that, accepting that music is part of the experience of every human culture group, we can say that it is an inherent gift given by a wise Creator for the benefit and enjoyment for us all. In his view, the church, in its missionary endeavours, ought to recognise and accept the powerful effect of music in all aspects of Christian ministry (Scott 2000:9), and therefore, employ it in its missionary work. Triebel (1992:235) endorses this observation by stating that we cannot ignore culture in our missionary task. Triebel (1992:235) is a positive example of a Lutheran missionary who thought about music in mission work. Triebel (1992:238) describes a project wherein new Christian songs are collected in Kiswahili for Tanzania, saying that, the use of indigenous music gives wings to the word of God in order to make it incarnate in Kiswahili.

From the arguments of the scholars cited in the text, there is general agreement amongst scholars that, in the African context, music is an intrinsic part of everyday life, as well as in religion. They assert that creativity provides the window through which music reveals with singular clarity just how the congregants can worship together. The issue of cultural relevance (to their liturgy) has therefore always engaged their attention. The results thus far suggest that the missionaries should have encouraged their converts to express their own feelings in praising God. However, further research needs to be undertaken in order to more fully understand the possible connection between traditional African religious music and liturgy.

Conclusion

The data is illuminative, however, the study would benefit from being supplemented by involving participants from other Evangelical Lutheran churches or mainstream churches. Such evidence should help to provide more definitive information in terms of the cultural impact of introducing traditional African religious music into liturgical church services. It is concluded that introducing traditional African religious music, whilst maintaining the Evangelical Lutheran liturgy, will increase member participation and attendance. It is therefore suggested that other Evangelical Lutheran congregations in Africa (that are losing church members because of poor attendance) could potentially consider introducing traditional African religious music as part of their church services.

This study contributes to the notion that traditional African religious music has a positive impact on mission work in the South African context. This knowledge may help us to understand the relevance of traditional African religious music in terms of mission and liturgy. Based on the findings of this study, it is suggested therefore that mainstream churches in South Africa - Lutheran churches in particular -ought to recognise and accept traditional African religious music as intrinsic to missionary work.

Recommendations for future research include investigations surrounding contextualisation and the importance of liturgy - with special emphasis on musical-liturgical forms. Other investigations could include the creative potential of traditional African religious music in liturgy. With further research leading to a greater understanding of this area, we may be in a position to develop a liturgy that expresses the joy and liberation of the gospel, which is appropriate for the South African context, which will reflect Lutheran theology, and will encourage maximum and unimpeded participation in worship by members.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the National Research Foundation (NRF) for their financial support.

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationships which may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

References

Amalorpavadass, D.S., 1971, Towards indigenization in the liturgy, St. Paul Press Training School, Dasarahalli. [ Links ]

Bosch, D.J., 2005, Transforming mission: Paradigm shifts in theology of mission, Orbis Books, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Calvin, J., 1960, 'Institutes of the Christian religion', in J.T. McNeill (ed.), Library of Christian Classics, p. 894, Westminster Press, Philadelphia, PA. [ Links ]

Chenoweth, V., 1984, 'Spare them Western music!', Evangelical Missions Quarterly 20(1), 31-37. [ Links ]

Chernoff, J.M., 1979, African rhythm and African sensibility: Aesthetics and social action in African musical idioms, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL, and London. [ Links ]

Chupungco, A.J., 1994, 'Die liturgie und bestandteile der kultur', in A. Stauffer (ed.), Lutherischer Welthund: Gottesdienst und Kultur im Dialog, Lutherisches Kirchenamt, pp. 151-163, Evangelische Haupt-Bibelgesellschaft, Berlin. [ Links ]

Darby, I., 1999, 'Broad differences in worship between denominations', in C. Lombaard (ed.), Essays and exercises in ecumenism, pp. 64-71, Cluster, Pietermaritzburg. [ Links ]

Dargie, D., 1989, 'Die kirchenmusik der Xhosa', transl. K. Hermanns, Concilium: Internationale Zeitschrift für Theologie 25, 133-139. [ Links ]

Dargie, D., 1997, 'South African Christian music: Christian music among Africans', in R. Elphik & R. Davenport (eds.), Christianity in South Africa: A political, social & cultural history, pp. 319-326, University of California Press, Berkeley, CA. [ Links ]

Dierks, F., 1986, Evangelium im afrikanischen kontext: Interkulturelle kommunikation beiden Tswana, Gutersloher Verlagshaus Gerd Mohn, Gütersloh. [ Links ]

Friesen, A.W.D., 1982, 'A methodology in the development of indigenous hymnody', Missiology: An International Review 10(1), 83-96. [ Links ]

Hunt, T.W., 1987, Music in missions: Discipling through music, Broadman, Nashville, TN. [ Links ]

Khuzwayo, L.B., 1999, 'Bodily expressions during worship', in Minutes of Church Council No. 90, pp. 17-19, Evangelical-Lutheran Church in Southern Africa, Lutheran Church Centre, Kempton Park. [ Links ]

Kraft, C.H., 1980, 'The church in culture: A dynamic equivalence model', in R.T. Coote & J. Scott (eds.), Down to earth. Studies in Christianity and culture - The papers of the Lausanne consultation on Gospel and culture, pp. 211-230, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Kritzinger, J.J., 1988, The South African context for mission, Lux Verbi, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Kubik, G., 2001, 'Africa', in The New Grove dictionary of music and musicians, 2nd edn., Macmillan, London. [ Links ]

Lieberknecht, U., 1994, Gemeindelieder: Probleme und chancen einer kirchlichen Lebensäu6erung, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen. [ Links ]

Lilje, D.R., 1992, 'The path of our Lutheran church into the future', in H.L. Nelson, P.S. Lwandle & V.M. Keding (eds.), Dynamic African theology: Umphumulu's contribution, pp. 94-113, Lutheran Theological Seminary, Umphumulu. [ Links ]

Maboee, C., 1982, Modimo Christian theology in Sotho context, Lumko Institute, Pietermaritzburg. [ Links ]

Mashiane, M.A.B., 2005, 'An assessment of the Constitution of the Evangelical Lutheran church in Southern Africa within the bill of rights as enshrined in the South African Constitution Act', Master's thesis, Dept. of Church History, University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

Mugambi, J.N.K., 1989, The African heritage and contemporary Christianity, Longhorn, Nairobi. [ Links ]

Nelson, H.L., 1996, 'Holy Spirit and Lutheran belief', in H.L. Nelson (ed.), Calls, gathers and enlightens. Lutheran views on the Holy Spirit - Festschrift Gert Landmann, pp. 23-56, Christian Literature Publishers, Kranskop. [ Links ]

Nelson, D., 1999, 'Crossing the music threshold - Culturally attuned music fosters communion with God', Evangelical Missions Quarterly 35(2), 152-155. [ Links ]

Nketia, J.H.K., 1974, The music of Africa, W.W. Norton & Company, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Nzuza, T.D., 2009, 'The unfinished task of the Evangelical Lutheran mission during the 21st century in the Northern Diocese, focusing much on the comprehensive mission of the church', Master's thesis, Dept. of Science, Religion and Missiology, University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

Rapetswa, P., 2001, 'Towards holistic mission, with special reference to the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Southern Africa, Northern Diocese', Master's thesis, Dept. of Mission and Religious Studies, University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

Reed, L.D., 1947, The Lutheran liturgy, Fortress Press, Philadelphia, PA. [ Links ]

Schrag, B.E., 1989, 'Becoming bi-musical: The importance and possibility of missionary involvement in music', Missiology - An International Review 17(3), 311-319. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/009182968901700306 [ Links ]

Scott, J., 2000, Tuning in to a different song - Using a music bridge to cross cultural differences, University of Pretoria, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Triebel, J., 1992, 'Mission and culture in Africa - A working report on Tanzanian experience', Africa Theological Journal 21(3), 232-239. [ Links ]

Whelan, T., 1990, 'African ethnomusicology and Christian liturgy', in T. Okure & P. van Thiel (eds.), 32 articles evaluating inculturation of Christianity in Africa, pp. 201-210, Association of Member Episcopal Conferences of Eastern Africa, Gaba Publishers, Eldoret. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Morakeng Lebaka

Private Bag X20

Hatfield0028,Pretoria

South Africa

Email:edwardlebaka@gmail.com

Received: 10 June 2014

Accepted: 21 Feb. 2015

Published: 04 June 2015

Note: Dr Morakeng Edward Kenneth Lebaka is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow, with Prof. Dr Dirk Human as supervisor, Department of Old Testament Studies, Faculty of Theology, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa.

1.There are many delightful references to music by Luther; for example, 'Next to the Word of God, the noble art of music is the greatest treasure in the world! I truly desire that all Christians come to love and regard as worthy the lovely gift of music, which is precious, worthy, and costly treasure given to mankind by God ... It controls our thoughts, minds, hearts, and spirits ... It is without reason that our dear fathers and prophets desired that music always be used in churches. Hence we have so many songs and psalms'.

2.Cf. Maboee (1982); Whelan (1990);Dargie (1989, 1997);Lieberknecht (1994); Chenoweth (1984); Kraft (1980); Nelson (1996); Reed (1947); Rapetswa (2001); Mashiane (2005);Nzuza (2009);and Khuzwayo (1999). The issue of cultural relevance (to their liturgy) has therefore always engaged scholars and/or theologians' attention.

3.The word 'mission' has become an issue of contention in theological circles. It originates from the great command by Jesus, when he ordered his disciples to take the Good News to the end of the world (Mt 28:10-16). It is the involvement of the whole Trinity and encompasses the extension of the kingdom of God the world over. Kritzinger (1988:33) regards mission as evangelism; that is, the communication of the Good News of salvation to those outside the church.

4.Schrag (1989:313) explains that each music system is governed by its own set of rules for creation and comprehension, and creates emotional responses in those who know it, which no other music can do. This fact makes it so vital for a missionary to first understand her or his own musical heritage and only then encounter the other musical traditions.

5.Congregations and church choirs build a repertoire that is characterised by a cultural blend, polyrhythm, improvisation and four-part harmonic setting, which compel the whole congregation to dance to the music, and hence increase attendance and participation.

6.Whelan (1990:202), for instance, has observed that many local churches have begun to produce a body of liturgical music that is a worthy cultural expression of their Christian faith. Furthermore, Chenoweth (1984:35) gives a few examples showing the 'fruits of indigenous musical leadership in the church' which have resulted 'in a wealth of worship styles all over the world', such as those of Papua New Guinea, Nigeria or Cameroon.

7.Dargie (1989:138) endorses this observation by stating that African hymns will certainly contribute to the renewal of the whole church. The relevance of, for instance, isiXhosa music to mission and church is expounded by Dargie (1997:319-326).