Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

HTS Theological Studies

On-line version ISSN 2072-8050

Print version ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.70 n.1 Pretoria Jan. 2014

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Leadership mentoring and succession in the charismatic churches in Bushbuckridge

Richard M. Ngomane; Elijah Mahlangu

Department of Religion and Biblical Studies, University of Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Leadership mentoring and succession programmes are critical in the development and preparation of emerging leaders for leadership transitions. By virtue of their one-founder-leaders whose special leadership talents are usually celebrated by their followers, Charismatic church leaders may fail to identify and develop young emerging leaders who may be equally gifted to prepare them for leadership succession. This quantitative study investigated the state of leadership mentoring and succession programmes in the Charismatic churches in Bushbuckridge, Mpumalanga, South Africa (Bushbuckridge is one of five local municipalities in the Ehlazeni District Municipality situated in the north-east of the Mpumalanga province in South Africa. It borders private game ranches and the Kruger National Park). A population of 287 respondents drawn from 48 churches from rural and urban locations was assessed. Many of them (85%) were reported to have leadership mentoring programmes in their congregations and 72% of them reported that they had leadership succession programmes in place. Location was found to have no statistically significant effect on leadership mentoring. Gender and education levels were reported to have a statistically significant effect in describing leadership mentoring. Charismatic groupings in Bushbuckridge believe and take the Bible seriously as authoritative for faith, life and ministry. We therefore think it is appropriate to include in this article a relevant illustrative text - 2 Timothy 2:1-3.

Introduction

Leadership mentoring and succession has been extensively researched and practiced in the business world, so much so that Charismatic church leaders who are serious about developing emerging leaders can only ignore it at their own peril. A study of leadership emergence patterns in the Bible reveals that many leaders, whether by coincidence or by design, had understudies they mentored to whom they handed over the 'baton' at the end of their ministries. This is evident in such Old Testament examples of mentoring relationships as Moses and Joshua, Eli and Samuel, and Elijah and Elisha (Angel 2009:145; Hurowitz 1994:483; Jos 1:1-3; 2 Ki 2:15; Kislev 2009:430; 1 Sm 3:8).

The New Testament leaders starting with Jesus did not deviate from the norm of mentoring leaders for leadership succession. A priority for Jesus was the recruitment of disciples even before he took his ministry to the public domain (Jn 1; Mt 4; Mk 1-2; Lk 5). New Testament leaders such as Barnabas and Paul left a legacy of leadership mentoring and succession for the current church to learn from.

Theoretical review

Any attempt to confine the assessment of leadership mentoring and succession to the researcher's field of study can only be realised at the cost of some of the best theories and practices championed in other disciplines. Lee (2003) has the following to say regarding work borrowed from other disciplines:

While drawing from secular writings may surprise some, it is well to remember that the church has often used insights from the secular world to further its course - philosophy to interpret its message, speech to proclaim it, psychology to enhance its pastoral care, and organizational development to strengthen its administration. The leadership skills and knowledge required in other disciplines are essentially the same as those required in the church. (p. 22)

The contributions that research in the business world and other social sciences have made to the subject of leadership mentoring and succession is so enormous that borrowing from them can only enhance this study. The church as part of a complex modern society is exposed to varied leadership development concepts and strategies across many disciplines. The need for leadership mentoring and succession plans cuts across all types of organisations - for profit and not-for-profit alike. For this study, literature from both the business and biblical perspectives was reviewed.

Leadership mentoring and succession in the business world

The world of business is replete with literature on the subject of mentoring and succession. Organisations that run effective mentoring programmes usually recruit candidates from within to fill senior positions (Collins & Porras 2004:173). In the modern highly competitive global business environment, it is becoming increasingly difficult for companies to attract from the market competent leaders who will place their organisations at the cutting edge. Well-designed mentoring programs offer a powerful and strategic tool for organisations to develop and retain talent within their own workforce. The costs of traditional human resource development, such as classroom training, compels companies to consider alternative and cost-effective means of staff development, one of which is mentoring (Murrell, Forte-Trammell & Bing 2009:3).

Authors differ in their definitions of mentoring in that some emphasise the structural relationships of mentoring functions, yet others gravitate toward the personal relationship side of mentoring. Structural relationships emphasise status and office power which legitimate the roles that mentors play to provide advice and sponsorship to their protigis. Those who emphasise personal relationships are developmental in their approach. Recently, mentoring literature tends to favour the inclusion of mentor-related roles and functions in the definition of mentoring (Gibson 2004:259). Waters et al. (2002) contend that:

Currently, definitions of mentoring tend to emphasise what seems to be a departure from the conventional one-to-one relationship between an experienced person (mentor) and a less experienced person (protigi), for the radical humanist perspective that goes beyond the functionalist approach. (p. 108)

Darwin (2000:8) avers, 'this approach to mentoring emphasises the development of an environment in the work place that encourages risk taking, dialogue and, horizontal relationships as a means of creating new knowledge' (see also Waters et al. 2002:108). One of the conditions for a successful mentoring programme is that the mentor and the protigi must enjoy a good relationship. It is in such a relationship that a mentor takes on roles as teacher, advisor, role model, sounding board, inspirer and developer (Gordon 2005:31; Meyer & Fourie 2006:43-49; Schmidt & Wolfe 2009:372).

Leadership mentoring and succession from a biblical perspective

Leadership mentoring and succession practices can be traced back to the Old Testament regime. Moses mentored Joshua (Angel 2009:145-146; Ex 32:17-18; Nm 11:27-29). Eli mentored Samuel (Bell & Treleaven 2010:9; Chao, Walz & Gardner 1992:620; Hurowitz 1994:483; Janzen 1983:89; 1 Sm 1:24-25). Moore (2007:161) presents Elijah as the strongest example in the Old Testament of a prophet as a mentor. Elisha's request for a double portion of Elijah's spirit (2 Ki 2:9) was a culmination of the leadership-succession plan which undergirded their relationship (Moore 2007:164). Elijah mentored Elisha (Angel 2009:146; Burnett 2010:286; Moore 2007:177). Elijah is reputed to have been one of the best examples in the Old Testament prophets who mentored other prophets.

Scripture is silent on Elijah's background in relation to who mentored him and to what extent he was exposed to the work of other prophets before he hit the road running as a fully-fledged prophet (1 Ki 17:1; Moore 2007:161). 'Elijah was an important prophet of the Old Testament closely associated with Moses and Jesus' (Schell 2009:428).

As if the Old Testament mentoring practices had become a norm for the New Testament, Jesus chose and mentored his disciples with the intent of charging them with the responsibility to take his message to the rest of the world (Mt 28:18-20). A cursory reading of the book of Acts reveals a continuation of biblical mentoring relationships. Barnabas mentored Paul. There is a general concern by some New Testament scholars that Barnabas's role has been downplayed and overlooked for too long (Bauckham 1979:62; Stenschke 2010:504). Branch (2007:297) regrets that although Barnabas had a decisive influence on the fate of the church in the 1st century, he now resides in obscurity. A closer look at Barnabas's role in the book of Acts reveals an impressive profile. Barnabas is said to have followed the ministry of Jesus from its inception to the end (Branch 2007:301; Read-Heimerdinger 1998:40; Ac 11:24). Barnabas emerged for the first time as Paul's mentor when the latter returned from Damascus out of fear of the Jews who conspired to kill him after he had converted to Christianity (Ac 9:26-27; Stenschke 2010:506). Stenschke (2010:507) contends that had it not been for Barnabas's intervention, Paul would have become an insignificant figure in Jerusalem. Barnabas believed in people. Branch (2007:306) contends, 'he believed the Lord could work with very unlikely candidates like a blood-thirsty persecutor and even with the uncircumcised Gentiles.' When news reached the apostles in Jerusalem that a Christian church was established in Antioch, the leaders sent Barnabas to go and encourage them. Being a Hellenist Jew, Barnabas was most probably the right man for the difficult mission (Ac 11:22; Branch 2007:309; Stenschke 2010:503-526). Having sized up the magnitude of the task at hand, Barnabas travelled to Tarsus to search for Paul and brought him to Antioch to mentor him (Stenschke 2010:503-526).

The successful mentoring relationship between Barnabas and Paul prepared the latter to be a mentor of other emerging leaders in their ministry. Timothy emerges as a protigi whom Paul loved and prepared to be his successor. Their relationship is a good example of New Testament leadership mentoring and succession (1 Tm 1:3, 1:18; 5:21; 2 Tm 4:6; Phlp 2:19-24; Holloway 2008:543). Paul recognised the importance of equipping a successor to carry on his leadership role after his own life and ministry were over (Hoehl 2011:35). Paul's leadership succession intent is clear in his instructions to Timothy (1 Tm 1:3, 18; 5:21; 6:13-14; 2 Tm 2:1-3). At the time Paul was in prison and could not move freely, he offered Timothy as his substitute to some of the churches, such as Philippi (Phlp 1:22; Holloway 2008:543).

Methodology

In this study, a combination of the qualitative and the quantitative methods were used. In the qualitative part of the study, interviews and focus group studies were used. Interviews were conducted with three of those who pioneered the Charismatic movement in South Africa and six of those who witnessed it when it was first introduced at Bushbuckridge. Focus group studies were conducted with three groups of the leaders of the Charismatic churches in Bushbuckridge. For the sake of space, only the quantitative part of the study is reported here.

From literature the researchers reviewed as well as interviews and focus group studies they obtained a feel for the type of questions they should ask respondents in the questionnaire. They then drew up a questionnaire and submitted it to the Department of Statistics (University of Pretoria) for formatting. The research questionnaire was distributed to all the 348 leaders in the 47 Charismatic churches in Bushbuckridge. Of the 348 questionnaires, 240 (69%) were distributed to rural and 108 (31%) to suburban churches. Of the 240 and 108 questionnaires, 203 (85%) and 84 (78%) respectively were returned. The questionnaires were delivered and collected door-to-door by the researchers and after collecting them, were coded by them according to the number range allocated to each congregation. The returned questionnaires were then grouped into rural and suburban churches and each respondent was allocated a congregation code and sequence number from 001 to 287, being the total number of respondents. The questionnaires were then submitted to the Department of Statistics (University of Pretoria) for data capturing and processing. A printout of the data as captured was returned to the researchers for corrections and confirmation. Minimal corrections were attended to and a final printout of the data was produced for storage.

Results and analysis

The process of data analysis comprised frequency determination of all variables, rural versus urban responses, one-way and two-way frequency tables, exploratory factor analysis, Cronbach's alpha determinations, confirmatory factor analysis, and the modelling of appropriate response variables against predictor variables using the analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Frequency analysis

A detailed frequency analysis was conducted of all the variables contained in the questionnaire. Two types of tables were produced, namely, one-way tables and two-way tables.

One-way tables

The frequency table of gender revealed that 47% (135) of the respondents were male and 53% (152) were female. It is interesting to note that in the data collected it showed that more women are involved in church leadership in the Charismatic churches of Bushbuckridge. It is also interesting to note that 90% (258) of the respondents are 50 years of age or younger. The youngest respondent was 16 years of age. The age of the respondents suggests that Charismatic churches in Bushbuckridge are still led by their founders, meaning that many of them have not yet experienced transitions to leadership positions. The age distribution further confirmed the fact that 92% (270) of the respondents have been in church leadership positions for 15 years or less and that 90% (257) of respondents have been fellowshipping in their congregations for 20 years or less.

Most of the respondents 85% (245) stated that they have mentoring programmes and 72% (247) stated that they have leadership and succession programmes in their churches. This contradicts the outcome of the three focus group studies which leads to the conclusion that the Charismatic churches in Bushbuckridge do not have leadership succession and mentoring programmes in place. The fact that in the focus groups respondents gave their opinions on the availability of leadership mentoring succession programmes in the Charismatic churches in Bushbuckridge and not on their own churches could be responsible for the change of opinions. It could be that in the focus groups, respondents responded truthfully but when asked in the questionnaire to indicate whether they themselves had leadership mentoring and succession programmes gave responses that seemed good to them in order for them to appear to be doing the right thing. If this was the case, then their credibility as church leaders is in question. One of the researhers, having been a member of the same Charismatic church community in Bushbuckridge all his life, aligns himself more with the outcomes of the focus group studies.

Most respondents 81% (232) indicated that they have protigis they are presently mentoring in their congregations and 84% (241) of them stated that they were convinced that the future of their Charismatic churches depended on their ability to mentor emerging leaders. Their claimed commitment to leadership mentoring and succession is confirmed by 66% (190) of respondents reporting that someone was ready to take over leadership should anything happen to them. The claims made by the focus groups that Charismatic churches in Bushbuckridge often experience leadership transition crises when a leader dies were refuted by 55% (157) of the respondents who indicated that they experienced smooth leadership transitions and 66% (190) of them who indicated that they are currently preparing someone to succeed them in the event of their death or retirement.

Two-way tables

Essentially the researchers investigated the relationship between rural and urban congregations and the aspects mentioned in section B of the questionnaire.1 This was determined by means of chi-squared tests. A chi-squared test is a statistical test often used for categorical data. It involves a comparison of observed and expected frequencies (Howell 2011:505). Two-way relationships of interest were the association between location and the following variables.

Tables 1a and Table 1b depict the relationship between the responses of urban and rural churches in relation to the future of their Charismatic churches depending on their leaders' ability to mentor emerging leaders.

Noticeable is the fact that although out of 84 urban churches, only 7% (6) disagreed, their cell chi-square is 4.1373. Although those who disagreed constituted a small number of the respondents in the urban churches, their opinion is so strong that they cannot be ignored. Their opinion is largely responsible for the large total chi-square (6.9658) as depicted by Table 1b. Given the probability of the p-value (0.0083), which is statistically significantly less than 0.05, it is logical to reject the null hypothesis, but the opinion of the minority is so strong that it deserves attention. A comparison between the responses of urban and rural congregations reveals interesting observations. Against the marginal 7% (6) of those who disagreed in the urban congregations, a sizeable 20% (40) out of 203 rural respondents disagreed. It is also interesting to note that although more respondents disagreed in rural congregations, their opinion as represented by the chi-square = 1.712, they did not have as strong an opinion as their urban counterpart. Looking at the total percentage of those who agreed in both urban and rural churches (84%) against the minority that disagreed (16%), it would be logical to ignore the opinion of the latter, but the total chi-square (6.9658) is so large that it demands attention. Instead of going by the opinion of the majority, the researchers would recommend a follow-up survey that seeks to find out why the minority (especially in the urban congregations) has such a strong opinion in favour of the null hypothesis. It would be interesting to know why they feel so strong that the future of their Charismatic churches does not depend on their ability to mentor emerging leaders.

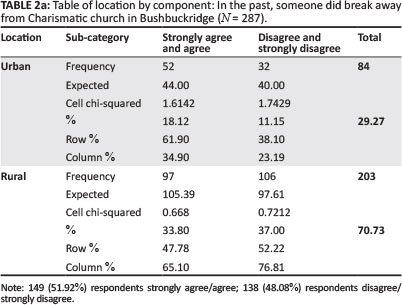

Tables 2a and Table 2b depict the relationship between the responses of urban and rural churches in relation to those who broke away from their congregations to start their own Charismatic churches. As depicted by Table 2a, out of 84 respondents in urban congregations, 44% (52) agreed that they experienced breakaways in their churches and 40% (32) disagreed. The split between those who agreed and those who disagreed is so small that it appears as if respondents from urban churches are not sure of their responses. This small margin is also represented in their respective chi-squares of 1.6142 and 1.7429 respectively. The opinion of the urban churches seems to be shared by the rural churches. This is evident in that in rural congregations, out of a total of 203 respondents, 34% (97) agreed and 37% (106) disagreed. Here too, the cell chi-squares of those who agreed and those who disagreed, 0.668 and 0.7212 respectively, are so close to each other that they do not represent a strong opinion by either group. As in the case of urban congregations, rural congregations that did not seem to be sure whether they agree or disagree, but their total chi-square (4.7463) as depicted by Table 2b, indicates that the opinion of those who disagreed is so strong that it cannot be ignored. Although the p-value (0.0294) suggests a rejection of the null hypothesis, the strong opinion of those who disagreed deserves attention. It would be interesting to run a second survey that would be directed at establishing the reasons for the strong opinions of those who disagreed.

Tables 3a and Table 3b depict the relationship between the responses of urban and rural churches in relation to the churches that have leadership succession programmes. As depicted in Table 3a, 63% (53) out of 84 respondents from urban churches stated that they have leadership mentoring programmes and 37% (31) stated that they do not have. A comparison of the chi-squares of those who agreed (0.9497) and those who disagreed (2.4573) reveals that although the former are in the minority, their opinion is quite strong. A similar situation prevailed in the rural churches. Although those who agreed in the rural churches are in the majority, their chi-square (0.393) did not represent an opinion as strong as that of those who disagreed (1.0168). Therefore, although those who disagreed are in the minority (24.14%), their strong opinion must be taken seriously. When put together, the opinions of those who disagreed in both the urban and rural churches is represented by a statistically significant chi-square (4.8168) as depicted in Table 3b. The corresponding p-value (0.0282) suggests a rejection of the null hypothesis, meaning that a conclusion should be drawn that the Charismatic churches in Bushbuckridge do have leadership succession programmes in place. However, the heavy-handed chi-square (4.8168) calls for a serious consideration of the strong opinion of those who disagreed. It would be advisable to conduct a second survey that will be aimed at establishing the reasons for the strong opinion of the Charismatic leaders who stated that they do not have leadership succession programmes.

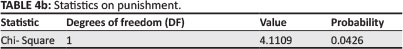

Tables 4a and Table 4b depict the relationship between the responses of urban and rural churches in relation to church leaders' tendencies to punish those who make mistakes in their congregations. As depicted by Table 4a, 31% (26) out of 84 respondents in the urban churches stated that they tended to punish those who made mistakes in their congregations. Those who indicated that they do not punish those who make mistakes represent 69% (58) of the respondents in urban churches. Although they are in the majority their chi-square (1.1651) is statistically significantly less than that of those who agreed (1.7426), meaning that those who agreed represent a much stronger opinion. Although the majority 69% (58) of urban church leaders indicated that they did not punish those who made mistakes, the strong opinion of those who stated that they do punish should not be ignored as it leads to the conclusion that rural churches do punish those who make mistakes. The urban churches however, seem to be certain that they do punish those who make mistakes. Looking at the chi-square (0.7211) of those who stated that they do punish mistakes in rural churches, it does not represent as strong an opinion as that of their urban counterparts. As depicted by Table 4b, the p-value (0.426) narrowly rejects the null hypothesis and the strong chi-square (4.1109) which is mainly made up of the strongly opinionated urban church leaders, suggesting that there is more punishment taking place in urban than in rural churches.

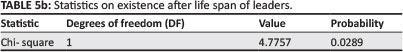

Tables 5a and Table 5b depict the relationship between the responses of urban and rural churches in relation to their churches' continuing to exist long after the lifespan of their leaders. Table 5a depicts that out of 84 urban respondents, 64% (54) agreed that they have plans for their churches to continue long after their lifespan and 36% (30) disagreed. A comparison of the chi-square (2.4717) of those who disagreed with those (0.9063) who agreed reveals that the former represent a very strong opinion. A similar situation is represented in rural churches. Although those who agreed are in the majority (54%), their chi-square (0.375) is statistically significantly less than the one representing those who disagreed (1.0228). As a result, the researchers cannot ignore those who disagreed. Also, although the p-value (0.0289) leads to the conclusion that the null hypothesis must be rejected, its corresponding chi-square (4.7757) which is mainly made up of the opinions of those who disagreed both in rural and urban churches suggests that those who disagreed must be taken seriously.

Factor analysis

An initial exploratory factor analysis was performed on the 51 variables of section B of the questionnaire. This initial factor analysis where the number of factors was not specified indicated 15 factors, which accounted for 62% of the variables in the data. The initial factor analysis process was repeated a number of times followed by a restricted factor analysis specifying 8, 7, and finally, 6 factors. A restricted factor analysis specifying 6 factors yielded a completely satisfactory result.

The Cronbach alpha coefficient was determined for the nine components of this Factor 1 (Table 6).

All deleted components were associated with alpha values that were very close to the raw Cronbach coefficient alpha (0.794484) indicating that they were well grouped as a factor. Components 1, 2, 3, 7, and 9 were included in this factor because they all deal with leadership development programmes to prepare emerging leadership for leadership succession. Components 4, 5, 6, and 8 were included in this factor because they focus on the behaviour of leadership that models leadership, emphasising vision, and ensuring emerging leadership of a good future in the Charismatic churches.

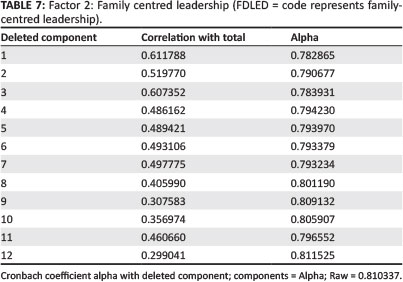

The Cronbach alpha coefficient was determined for the twelve components for Factor 2 (Table 7).

All deleted components were associated with alpha values that were very close to the raw Cronbach coefficient alpha (0.810337) indicating that they were well grouped as a factor. In the context of this study, family-centred leadership prefers leadership succession by family members usually due to financial considerations. Components 1, 2, 3, 6, 10, 11, and 12 were included in this factor because they relate to leaders' family members and behaviour that is motivated by financial considerations. Leadership succession by family members ignores the qualifications of those emerging leaders who are not members of the current leader's family and as a result it does not promote leadership development. Such leaders are likely to appear to be autocratic and threatened by those who are not members of their own families. This is the reason for the inclusion in the factor components 4, 5, 7, 8, and 9.

The Cronbach alpha coefficient was determined for the ten components of Factor 3 (Table 8).

All deleted components were associated with alpha values that were very close to the raw Cronbach coefficient alpha (0.719469) indicating that they were well grouped as a factor. In the context of this study, leadership mentoring requires a leader to be willing and able to mentor emerging leaders. Components 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, and 9 were included in this factor because they relate to a leader's qualifications in relation to and his or her involvement in mentoring. A healthy relationship between mentor and protigi is crucial for the success of a mentoring relationship. Factors 3, 6, 8, and 10 were included in this factor because they address mentoring relationships and synergy with other Charismatic churches.

The Cronbach alpha coefficient was determined for the seven components of this Factor 4 (Table 9).

All deleted components were associated with alpha values that were very close to the raw Cronbach coefficient alpha (0.670913) indicating that they were well grouped as a factor. Leadership mentoring and succession require long-term planning. Butler (2006:379) contends that the intellectual capital risks posed by the absence of a succession plan are greater in family businesses. Butler (2006:379) states that it is estimated that only 30% of family businesses survive in that form through to the second generation, and that only 10% survive to the third generation. Only a small percentage of family firms that plan for leadership succession are more likely to grow to become large businesses. By the nature of their one-man-founder leader, Charismatic churches are likely to experience the same leadership succession problems that are prevalent in family business structures. Focus group discussions cited nepotism as one of the reasons Charismatic church leaders tend to prefer leadership succession candidates who are members of their own families. The seven components were included in this factor because they relate to the leader's impartiality and confidence in choosing and empowering emerging leaders as well as his or her ability to leadership succession.

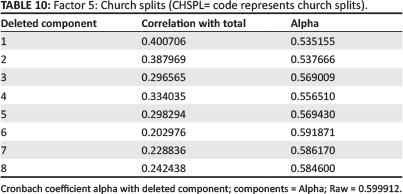

The Cronbach alpha coefficient was determined for the eight components of Factor 5 (Table 10).

All deleted components were associated with alpha values that were very close to the raw Cronbach coefficient alpha (0.599912) indicating that they were well grouped as a factor. Focus group discussions implied that many Charismatic churches in Bushbuckridge were started with wrong motives by those who led schisms. Components 2, 4, 5, 6, and 7 were included in this factor because they relate to schisms and motives for starting Charismatic churches. If many of those churches started with wrong motives, their founders will not have been prepared well for the responsibilities of founding new churches and may not relate well to the leaders of the churches from which they broke away. Components 1, 3, and 8 address leaders' qualifications, their ability to prepare emerging leaders for leadership succession in the process in which it is expected of them to allow their protigis to make and learn from their mistakes.

The Cronbach alpha coefficient was determined for the five components of Factor 6 (Table 11).

All deleted components were associated with alpha values that were very close to the raw Cronbach coefficient alpha (0.714652) indicating that they were well grouped as a factor. Focus group discussions in the qualitative part of this study implied that some leaders of Charismatic churches may be reluctant to mentor emerging leaders because they fear that as soon as their protigis feel qualified, they may lead schisms. Such leaders tend to prefer leadership candidates from their own family members over outsiders. Their fear may lead to even more schisms as those who are deprived of mentoring opportunities may sense that there is no room for growth in their churches and leave out of frustration. Charismatic church leaders' fears and the consequences thereof are addressed by all the components that are included in this factor.

The results of the analysis of variance processing

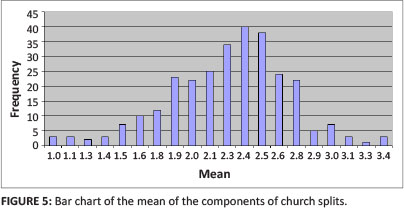

For each respondent, a set of six means were determined for each of the 6 Factors indicated in the confirmatory factor analysis. The frequency distribution diagrams for each of the six sets of means are indicated below.

Figure 1 displays the means of the components of leadership succession ranging from 1 to 3.3. The diagram shows that the means displayed on the X-axis are normally distributed, meaning that one is likely to get a proportionate number of observations on either side of the median of (2.0) of these means. The mean with the largest number of distributions is 1.8 followed by 2.2.

Figure 2 displays the means of the components of family-centred leadership. The dispersion is skewed to the right of the median (2.7). Means 2.8 and 2.9 have the largest and equal distribution of observations followed by 3.1 and 2.8.

Figure 3 displays the means of leadership mentoring. As in Figure 2 above, the means are normally distributed ranging from 1 to 3.1 on the X-axis. The observations are slightly distributed more to the left side of the median (2.05) than to the right with means 2.8 and 3 having the least numbers of observations. Mean 2 has the largest number of observations followed by mean 2.1.

Figure 4 displays the means of the components of long-term planning. The means are normally distributed and there is likelihood for a proportionate number of observations on either side of the median (2.0). Mean 2.0 has the largest number of observations followed by mean 1.9. Mean 3.7 has the least number of observations.

Figure 5 displays the means of the components of church splits. The observations are normally distributed as can be seen from the bell-shaped dispersion. With the median at 2.2, it is likely that there is a proportionate on either side of the median. The mean with the largest number of observations is 2.4 followed by 2.5 and 2.3.

Figure 6 displays the means of the components of leadership confidence. The diagram displays a skewed distribution with most of the observations dispersed to the right of the median (2.6). The mean with the largest number of observations is 3, followed by 3.4 and 3.6. This diagram does not depict a normal distribution of observations.

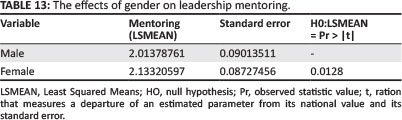

The researcher decided to determine the effect of gender and levels of education on leadership mentoring. It could have been possible to include in the same exercise such variables as respondents' age, leadership position and membership, but on examining the variables, the researcher decided to limit it to gender, levels of education and location. Location is not discussed here because the results of the ANOVA processing revealed that it has no effect on leadership mentoring. The diagrams below depict the effect that the levels of education and gender have on leadership mentoring respectively.

Table 12a displays the Least Squared Means (LSMEAN) values for the different levels of education in the analysis of variance where leadership mentoring is the response variable. For these pair-wise comparisons where the p < 0.05, the null hypothesis is rejected. The education level of respondents has definitely got a statistically significant effect on mentoring. It is interesting to note in the above tables that primary school and no-formal training have more effect on leadership mentoring than the other levels, with primary schooling having the greatest effect. Therefore, level of education can be used to indicate leadership mentoring. Table 12b displays p-values for the pair-wise comparison of LSMEANS values from Table 12a.

Table 13 displays the effect of gender on leadership mentoring, with p < 0.05, the null hypothesis that gender has no effect on leadership mentoring is rejected. Gender has definitely got a statistically significant effect on describing leadership mentoring.

Illustrative text (2 Tm 2:1-3)

The pastorals are an epistolary collection of the last instructions of Paul to Titus and Timothy and they include instructions on church discipline, appointment of officers and combating false teachers, and aim at helping leaders to guide the Christian communities (Nardoni 1998:1730). Powell (2009:398) sees in this text Paul charging Timothy to see to it that his teachings are passed on to the next generation. Hanson (1966:82) maintains that in this text perhaps the closest thing to the doctrine of the 'apostolic succession' that one can find in the Bible is present. Barentsen (2011:262) argues very strongly that from 2 Timothy 2:1ff., Paul orchestrates the transmission process of his own teaching tradition through Timothy to other leaders. The model of transmission is indicated in the central charge 'to strengthen' and to 'entrust to faithful men' (2 Tm 2:1-2). The object of transmission is indicated in the phrase 'what you heard from me' (2 Tm 2:2), which repeats similar wording from 1:13, so that the oral transmission is in view. Paul here speaks of the content to be transmitted as 'a pattern of sound' (2 Tm 1:13).

'The authority of transmission is illustrated by the stock examples from the popular diatribe that Paul had already used in 1 Corinthians 9:7, 24' (Barentsen 2011:263f.). Each illustrates a particular aspect of the leadership required of Timothy. Timothy is to endure suffering like a soldier of Christ Jesus (2 Tm 2:3-4); he is to compete according to the rules of an athlete (2:5); and like the farmer, and Timothy is entitled to receive benefits from his labours (2:6). After thus orchestrating the model, object and authority of transmission, Timothy was to be guided by the remembrance of Christ (Μνηµόνευε, 2 Tm 2:8; cf. 1 Tm 1:3-5), who also inspired Paul (2 Tm 2:8-10) to endure suffering. The faithful saying (2:11b-26) stirred Timothy to also accept suffering while transmitting Paul's gospel (2:14a), and to demonstrate himself as 'approved' and an 'unashamed' worker (2:15). The key factor in this passage (2:14-26) is Timothy's intra-group status relative to opponents like Hymenaeus and Philetus, with whom he differed extensively.

Conclusion

Most of the respondents (85%) reported that their churches had leadership mentoring programmes in place. Although many (84%) reported that the future of their churches depended on their ability to mentor emerging leaders, the few (16%) that did not agree represented a very strong opinion (chi-square = 6.9658) that justifies a follow-up assessment. As far as leadership succession programmes are concerned, 72 % of respondents reported that their churches had them in place, but 28% disagreed. The opinion of those who disagreed was so strong that it cannot be ignored (chi-square = 4.8168). Many of the respondents (52%) reported that they had experienced breakaways in the past. The high rate of church splits is concerning and calls for a follow-up study to determine the causes for the splits. The study revealed that leadership mentoring can be influenced by the levels of education and gender. The study also revealed that location has no significant statistical effect in explaining leadership mentoring - meaning that as far as leadership mentoring is concerned, urban churches have no advantage over rural churches. The illustrative text (2 Tm 2:1-3) serves as a model for leadership mentoring and succession. In this text, Paul invites Timothy and indeed all leaders to take leadership mentoring and succession seriously. Paul enlisted local leaders to look toward Timothy as model for their own leadership.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationship(s) that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

This article is part of R.M.N.'s doctoral thesis (University of Pretoria) and E.M. (University of Pretoria) was the promoter.

References

Angel, H., 2009, 'Moonlight leadership: A midrashic reading of Joshua's success', Jewish Bible Quarterly 37(3), 144-153. [ Links ]

Barentsen, J., 2011, Emerging leadership in the Pauline mission, Pickwick Publication, Eugene. [ Links ]

Bauckham, R., 1979, 'Barnabas in Galatians', Journal for the Study of the New Testament 2, 61-70. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0142064X7900100204 [ Links ]

Bell, A. & Treleavan, L., 2010, Mentee selection of mentors in a formal mentoring program, Springer, Sydney. [ Links ]

Branch, R.G., 2007, 'Barnabas: Early church leader and model of encouragement', In die Skriflig/In Luce Verbi41(2), 295-322. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ids.v41i2.307 [ Links ]

Burnett, J.S., 2010, '"Going down" to Bethel: Elijah and Elisha in the theological geography of the Deuteronomistic history', Journal of Biblical Literature 129(2), 281-297. [ Links ]

Butler, D., 2006, Enterprise planning and development: Small business start-up survival and Growth, Elsevier, Burlington, MA. [ Links ]

Chao, G.T., Walz, P.M. & Gardner, P., 1992, 'Formal and informal mentorships: A comparison of mentoring functions and contrasts with nonmentored counterparts', Personnel Psychology 45, 619-636. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1992.tb00863.x [ Links ]

Collins, J. & Porras, J.I., 2004, Built to last: Successful habits of visionary companies, Random House, Houghton. [ Links ]

Darwin, A., 2000, 'Critical reflections on mentoring in work settings', Adult Education Quarterly 50(3), 1-13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/07417130022087008 [ Links ]

Gibson, S.K., 2004, 'Mentoring in business and industry: the need for a phenomenological perspective', Mentoring and Tutoring 12(2), 259-275. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1361126042000239974 [ Links ]

Gordon, S., 2005, 'Choose a mentor who will push you out of your comfort zone to reap maximum benefit', in Computer Weekly.com, viewed 19 October 2010, from http://www.computerweekly.com/opinion/Choose-a-mentor-who-will-push-you-out-of-the-comfort-zone-to-reap-maximum-benefit [ Links ]

Hanson, A.T., 1966, The pastoral letters: commentary on the first and second Letters to Timothy and the letter to Titus, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Hoehl, S.A., 2011, 'The mentor relationship: An exploration of Paul as loving mentor to Timothy and the application of this relationship to contemporary leadership challenges', Journal of Biblical Perspectives in Leadership 3(2), 32-47. [ Links ]

Holloway, P.A., 2008, 'Alius Paulus: Paul's promise to send Timothy at Philippians 2:19-24', Cambridge Journals 54, 542-556. [ Links ]

Howell, D.C., 2011, Fundamental statistics for the behavioral sciences, Cengage Learning, Wadsworth. [ Links ]

Hurowitz, V.A., 1994, 'Eli's adjuration of Samuel (1 Samuel III 17-18) in the light of a "Diviner's Protocol" from Mari (AEM 1/1, 1)', Vestus Testamentum XLIV 44(4), 483-497. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1535108 [ Links ]

Janzen, J.G., 1983, 'Samuel opened doors of the house of Yahwher (1 Samuel 3:15)', Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 26, 89-96. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/030908928300802605 [ Links ]

Kislev, I., 2009, 'The investiture of Joshua (Numbers 27:12-23) and the dispute on the form of the leadership in Yehud', Vestus Testamentum 59, 429-445. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/156853309X436313 [ Links ]

Lee, H.W., 2003, Effective church leadership: A Practical Sourcebook, Ministerial Association, Silver Spring, MD. [ Links ]

Meyer, M. & Fourie, L., 2006, Mentoring and coaching: Tools and techniques for implementation, Knowres Publishing, Randburg. [ Links ]

Moore, R.D., 2007, 'The prophet as a mentor: A crucial facet of the biblical presentations of Moses, Elijah, and Isaiah', Journal of Pentecostal Theology 15(2), 155-172. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0966736907076334 [ Links ]

Murrell, A.J., Forte-Trammell, S. & Bing, D., 2009, Intelligent mentoring: How IBM creates value through people, knowledge, and relationships, IBM Press, Boston, MA. [ Links ]

Nardoni, E., 1998, s.v. 'Introduction to the pastorals', in W.R Farmer, A. Levoratti, D.L. Dungan & A. LaCocque (eds.), The international Bible commentary: A Catholic and ecumenical commentary for the twenty-first century, The Liturgical Press, Collegeville, pp. 1730-1843. [ Links ]

Powell, M.A., 2009, Introducing the New Testament, Eerdmanns, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Read-Heimerdinger, J., 1998, 'Barnabas in Acts: A study of his role in the text of Codex Bezae', Journal of the Study of the New Testament 72, 23-66. [ Links ]

Schell, T., 2009, 'The role of Elijah in Ulysses' metempsychosis', Texas Studies in Literature and Language 51(4), 426-146. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/tsL0.0043 [ Links ]

Schmidt, J.A. & Wolfe, J.S., 2009, 'The mentor partnership: Discovery of professionalism', NASPA Journal46(3), 371-381. [ Links ]

Stenschke, C.W., 2010, 'When the second man takes the lead: Reflections on Joseph Barnabas and Paul of Tarsus and their relationship in the New Testament', Bulletin for Christian Scholarship 75(3), 503-526. [ Links ]

Waters, L., McCabe, M., Kiellerup, D. & Kiellerup S., 2002, 'The role of formal mentoring on business success and self-esteem in participants of a new business start-up program, Journal of Business and Psychology 17(1), 107-121. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1016252301072 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Richard M. Ngomane

Email: drngoe@gmail.com

PO Box 2070

Hazyview 1242

South Africa

Received: 07 Sept. 2013

Accepted: 15 Mar. 2014

Published: 22 Aug. 2014

1. Section A of the questionnaire comprised of respondents' biographical data.