Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

HTS Theological Studies

On-line version ISSN 2072-8050

Print version ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.70 n.1 Pretoria Jan. 2014

ORIGINAL RESEARCH: APPLIED SUBJECTS - PRACTICAL THEOLOGY AND MISSIOLOGY

Cura animarum as hope care: Towards a theology of the resurrection within the human quest for meaning and hope

Daniel J. Louw

Department of Practical Theology, University of Stellenbosch, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The following critical questions are posed: is hope the antidote of dread and despair or a kind of escapism from the harsh realities of anguish and suffering? What is meant by hope in Christian spirituality and how is hope connected to a theology of the resurrection? Is resurrection hope merely a kind of cheap triumphantalism and variant of a theologia gloriae? The basic assumption is that the notion of the resurrection can contribute to 'the thickening of alternative stories of faith'. A theologia resurrectionis is about the reframing of life by means of a radical paradox: 'Where, O death is your victory? Where, O death is your sting?' If pastoral caregiving is indeed about change and hope, the resurrection describes an ontology of hope by which human beings are transformed into a total new being. Beyond the discriminating and stigmatising categories of many social and cultural discourses on our being human, resurrection theology defines hope as a new state of mind and being. The identity of human beings is therefore not determined by descent, gender, race or social status, but by eschatology (new creation.) Hope care is primarily about a new courage to be. It opens up different frameworks for meaningful living within the realm of human suffering.

Despair: The sickness onto death within the abyss of nothingness

The vital and relevant question regarding hope in spiritual care and healing is whether hope is not an escape from the present and a futile exercise, merely to bypass the existential realities of the now. Is the attempt to hope not irrational and absurd? As Albert Camus (1965) pointed out:

For if there is a sin against life, it consists perhaps not so much in despairing of life as in hoping for another life and in eluding the implacable grandeur of this life. (p. 122)

Whoever wants to reflect on hope, will immediately be disillusioned by the existential reality of death. Dread, despair, fear and death demarcate the decor of human suffering and our quest for meaning.

In his book on the concept of dread, Søren Kierkegaard (1967:37) made a profound statement regarding the essence of our being human: 'Spirit is dreaming in man'. Spirit is connected to pathos [sympathy], imagination and the possibility of anticipation.

However, when one is convinced that there is nothing (Sartre 1943, L'Etrê et le Néante), dread and nausea (disgust) set in. For Sartre, nothingness is a structural and constitutive element of being. Nothingness is a kind of existential parasite that hunts and pursues being (Sartre 1943:47). The attempt to hope becomes a futile exercise.

'But what does nothing produce?' asked Kierkegaard (1967:38). It can produce fear in the dreaming spirit. A human person is then delivered to the strange ambiguity of dread: 'Dread is sympathetic antipathy and an antipathetic sympathy' (Kierkegaard 1967:38). Dread constitutes a kind of neutral state of static innocence: the deepfreeze of the dreaming spirit, an antipathy that robs hope of its sympathy. Caregiving then becomes a soulless flirting with dread.

Homo viator as homo prospectans: Hope as spiritual category and principle of change (docta spes)

With reference to the French philosopher G. Marcel (1962) one can argue that a human being is essentially a homo viator [wanderer] and therefore aware of the transcendent realm of life. In essence hope entails more than merely optimism and speculative wishful thinking:

Hope is essentially ... the availability of a soul which has entered intimately enough into the experience of communion to accomplish in the teeth of will and knowledge, the transcendent act - the act establishing the regeneration of which this experience affords both the pledge and the first-fruits. [And] Hope is only possible on the level of the us, or we might say of the agape [Christian love]. (Marcel 1962:10)

Hope should therefore not be rendered as the antipode of dread and despair. Hope is essentially a spiritual category and is inter alia about change and the expectation of something new and different. Within the absence of a meaningful future and the anticipation of constructive change, regression sets in and the real danger lurks that a human being can become a victim of his or her past.

With hope in caregiving is not meant a kind of positive mood as the antipode for human anxiety (Buhr 1960:371), a sort of emotional reaction to dread or mood swing (Edmaier 1968:49), or as E. Brunner (1953:7) argued, hope as the positive antipode to the negativity of anxiety. Hope is a qualitative category and describes habitus [the attitude and aptitude of the human soul, indicating disposition and orientation].

When one reflects on the different cultural settings of our being human in history and time, it seems that a kind of religious awareness regarding transcendence is fundamental to our being human. A human being projects a kind of sensitivity for the ultimate factor in life which in many religious traditions is connected to a sense for divine presence and intervention. In the wisdom tradition of faith and hope the anthropological implication is that life implies 'more' than merely empirical factuality. To reckon with the transcendent factor in life brings about a kind of openness towards the future. It often triggers awe and a kind of curious anticipation of the future. It brings about the wisdom that life is not complete and that one should reckon in hope with the fact that within the already, the not-yet is a vivid component of life. In existential terminology it means that a human being is fundamentally designed towards future expectations: a homo pro spectans [a human being as an anticipating and future oriented being] (Polak 1968:271). Due to the not-yet factor, life is never complete and our being human always incomplete and unfinished, thus the notion of homo absconditus [the essence of being is a mystery, hidden in the not-yet of human existence].

What then is the contribution of an eschatological understanding of the future to spiritual growth and health?

Is it possible to merge hope to care, help, healing, counselling and therapy? But what is unique in the Christian tradition regarding the characteristics of hope? Is it merely an emotional category on the level of the affective, a mood swing dealing with need-satisfaction and wishful thinking? Is hope merely the prognostic projection of a better future or the restoration of loss in terms of past categories? Is the Christian variation of hope, a category sui generis and what is the difference between future as futurum [prophetic projections and temporal forecasts], future as utopia [the not-yet of something that does not exist, created by imagination and the creativity of the human mind], and future as parousia [the Second Coming, an eschatological understanding of a messianic expectation - the not-yet - in terms of the essence and identity of our being human, the ontological category of the already]?

According to D. Capps, to 'heal' and to cure the cura animarum [human soul] (Nauer 2010:55-57) is basically about change (Capps 1990:3). D. Augsburger (1986:349) argues that the purpose of counselling is threefold: choice, change and clarity. Within the framework of Capps's own approach, change is basically about reframing, that is to reveal that what appeared unchangeable can indeed be changed and that there exist superordinate alternatives (Capps 1990:62). To reframe means to 'change' the conceptual and/or emotional setting or viewpoint in relation to which a situation is experienced and to place it in another frame or paradigm (pattern of thinking) which fits the facts of the same concrete situation equally well or even better, and thereby changes its entire meaning (Capps 1990:17).

Campbell and Cilliers (2012:31) connect the method of reframing with the notion of paradox as an instigator of radical change. Theology is actually about reframing. They argue that through shocking paradoxes Paul subverts the endoxa [the conventional categories and commonly held convictions of honour and glory], drawing on conventional language and assumptions only to interrupt them and call them into question. 'Paul, however, relies on paradox - para-doxa - that which is situated beside or outside (para) opinion (doxa)' (Campbell & Cilliers 2012:31).

Arguing and thinking along the lines of Pauline theology, one is compelled to pose the following theological question: is the notion of the resurrection in Christian faith not the most fundamental paradox in theology?

The basic thesis of biblical faith and hope is: if Christ has not been raised, our faith is futile (1 Cor 15:17). Without the perspective of the resurrection in Christian spirituality, one should admit that Jean-Paul Sartre is totally correct: nausea dictates and demarcates the meaning of life. However, with a 'subtle ironic smile', Paul in 1 Corinthians 15 toyed with the idea that death is, from the perspective of resurrection faith, like a snake without poison. The latter is actually impossible, thus the strange paradox: 'Where, O death, is your sting?' (1 Cor 15:55).

The German philosopher Ernst Bloch introduced the principle of docta spes [principle of hope] as an ingredient of the dialectical process in matter and in the confrontation with nothingness. Camus argued that hope kills the spirit of revolt. In contrast Bloch (1970:186-193) advocates for hope as a fundamental element in an attitude of resistance and contradiction. Hope, as a utopian spirit, is for Bloch connected to the spiritual realm of human freedom and the quest for dignity and equality.

In Christian spirituality, hope in caregiving is essentially connected to compassion: compassion as the representation of God's hësëd, rëchëm and splanchnizomai [unconditional love and pity] (Davies 2003:252-253). Compassion then leads to the establishment of human dignity.

Towards a theologia resurrectionis

With reference to the challenge put forth by C. Landman that practical theology needs 'religious discourses on healing' that contribute to 'the thickening of alternative stories of faith' (Landman 2009:262-269) within the realm of township life, it is my contention that the narrative of the resurrection is one mode of a 'theological thickening for an alternative story' that contributes to hope and healing. Resurrection faith implies the praxis of action and resistance. Resurrection hope does not lead to neutral passivity but is in essence transformative: it deconstructs and unmasks all forms of discriminating practises that can rob human beings from their dignity.

The impact of the resurrection on Western theology theory formation has been surprisingly minor (Smit 1983:8). In the area of systematic theology, the resurrection was especially frequently underplayed due to the central position of the doctrine of atonement and a theologia crucis [the theology of the cross]. Berkhof (1973:332) attributes this diminished role accredited to the resurrection to the fact that Western sobriety ensured that the resurrection, as a central tenet of salvation, nevertheless always stood in the shadow of the cross. This diminution of the resurrection is also concomitant with the way in which Western theology concentrated on the works of Christ, in contrast to the Eastern Church's focus on the person of Christ.

Lekkerkerker (1966:134) believes that the Eastern Church saw Christ's suffering and death more in terms of a victory over the powers of evil, and could thus sense the triumph of the resurrection. In its doctrine of atonement, the Western Church concentrated more upon the juridical and forensic dimensions of the cross as liberation for the sinner. Another factor which could have contributed towards an underemphasis on the resurrection is the so-called process of secularisation and technological development. Within a very rationalistic and positivistic model it seems that there is little scope for a gospel of resurrection.

From a traditional and doctrinal perspective, it would appear that the doctrines of soteriology and the incarnation headed the theological agendas of the different councils. After the Arian controversy and the emphasis placed on the Divinity of Christ by the Council of Nicea, the resurrection tended no longer to be in the forefront of theological discussion. The resurrection frequently had to serve as merely a final proof of the Divinity of Christ, not as the foundation of the whole of dogmatic reflection. Ultimately, the resurrection became only a necessary consequence of the cross, within the successive phases of humiliation and exaltation. According to Gesche (1973:275-324) the resurrection played the role of an additional legitimising factor. The resurrection served as proof either of the mission of Christ, or the truth of the scriptures, or the Divinity of Christ, or of the effectiveness of Jesus' work of salvation.

However, one can argue that the message of resurrection forms the heart and core of New Testament theology. From the perspective of the resurrection the existing situation of the early church could be analysed in view of its transformation and its focus on the future. The resurrection message forms the basis of New Testament theology (Goppelt 1980:56): it is actually the root and heart of New Testament theology (Goppelt 1980:58).

In view of the central role of hope in theology, Guthrie (1981:389) asserts that '[t]he reality of the resurrection is, therefore, an indispensable basis for Christian hope in the future'. According to him, the resurrection is not only important for the theme of hope, but it also has a Christological significance. It focuses particularly on Christ's person and work (Guthrie 1981:390). For Guthrie, faith in the resurrection provides the necessary continuity for the notion that Jesus is truly God and truly human. As an act of God, the resurrection also has implications for traditional God-images. The message of the resurrection is also decisive for the preaching of the gospel (Guthrie 1981:460).

A number of other authors are also conscious of the important role which the resurrection plays in theology. Jonker (1983:139) believes that the resurrection plays an important role in the panorama of God's salvific deeds. In the gospel of salvation, the message of the risen Christ stands alongside the outpouring of the Holy Spirit. Redemption is an eschatological reality and has a victorious perspective.

Berkouwer (1961:231-246) regards Paul's ministry as a symbol of a resurrection hope. He considers the resurrection as fundamental for the eschatological perspective of the gospel. A distinction needs to be made between the resurrection as a salvific reality and the resurrection as a future reality where the mortal will be clothed with immortality. The latter forms part of the former, so that both become determining factors in the dynamic of Christian hope. The resurrection plays a major role in Karl Barth's theological reflection (1953:329332). He views the resurrection as an act of God. Whilst the cross is the judgement of grace, the resurrection is the grace of the judgement. Any human achievement falls away in the resurrection. Barth regards the resurrection as being so important that he describes the act of resurrection as an act of salvation from which everything else needs to be understood: it is an Offenbarung uberhaupt (Barth 1953:332). Barth stresses the resurrection in such a way that God the Father becomes the complete subject of the resurrection. It is exclusively a work of God, without any co-operation from the Son. The resurrection is thus not a consequence of Jesus' death on the cross, but as a sovereign act of God the resurrection indicates God's gracious compassion and trustworthiness (Barth 1953:335). Barth (1953:335-336) states that the theologia resurrectionis is an independent, new work of God, which confirms the validity of Christ's suffering. The cross and the resurrection is one historical act in which God proclaims and finally confirms his 'Yes' of reconciliation to the sinful world. The cross and resurrection form such an indivisible unity within the history of salvation that only one form of theological reasoning can be derived from the uniqueness of the cross and the historicity of the resurrection: forward from the resurrection, not backwards from the parousia. The time in which the community lives is always determined qualitatively from the resurrection as parousia.

According to Guthrie (1981:390), the resurrection is not only important for the theme of hope, but it also has a Christological significance. It focuses particularly on Christ's person and work. For Guthrie, faith in the resurrection provides the necessary continuity for the notion that Jesus is truly God and truly human. Resurrection and suffering are two themes that cannot exist separately. Simon (1967:101) does not regard the resurrection as an easy way out of suffering and pain, but it incorporates them into a new perspective on life. Resurrection faith does not retreat from the reality of suffering, but confirms the tragedy of suffering.

In Jürgen Moltmann's theology of hope (1966), the resurrection plays a crucial role in revealing the meaning and gospel of the cross. Within Moltmann's notion of eschatologia crucis, the cross is not limited to Christ's reconciliatory work, but becomes a symbol for the eschaton [fulfilment and completion of Christ's mediatory work of salvation as final or last proof of the faithfulness of God] of Christ: the resurrection. The resurrection opens up a future perspective in such a way that the resurrection obtains an eschatological primacy over the cross. Eschatology, derived from the resurrection, reveals the hope principle embedded in the cross. Hope is actually resurrection hope (Moltmann 1995:12).

Schutz (1963:351), to a certain extent following Moltmann's view, considers the resurrection to be the Ereignis [fundamental, primary and constitutive event] which forms the basis and norm of all discussion about the future. Ott (1958:18) believes the Easter events ensure that the message of Jesus'' resurrection became Der Auferstandene ist der Eschatos, the foundation and source of Christian eschatology.

According to Moltmann (1995:12) a Christian eschatology should not be reduced to apocalyptic solutions regarding the end of creation. The primary theme and formula of an eschatology is not 'the end' but 'the essence' (the new beginning) of everything. It is about the new creation through which all beings received a new quality: the dawn of a radically new life (resurrection), hence the reason for hope. Christian hope is an ontic principle and opens up new avenues for, and new ways of, being.

De Jong (1967:71) refers to the role of the historical-critical model, the intellectual emphasis which left little scope for the miracle of the resurrection. The Formgeschichte also relativised the gospel of resurrection. The implication is that resurrection faith becomes deprived from its historical context and is reduced to merely a speculative, subjective mode in the memory of Jesus' disciples.

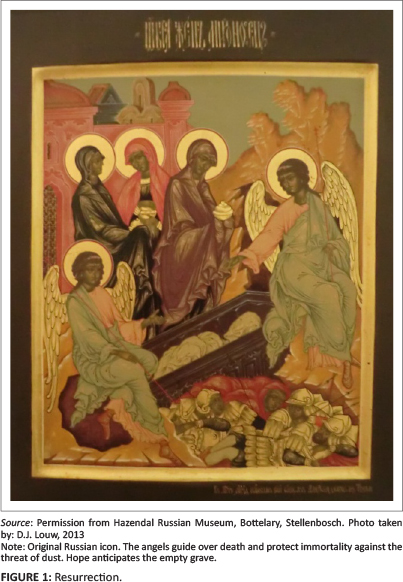

The resurrection should not be limited to the dimension of personal faith alone, exclusive of the cosmic dimension (De Jong 1967:69-70). Contemplation of the 'empty grave' does not make faith superfluous, but confirms it (Figure 1).

Therefore faith cannot ignore the empty grave. Faith in the risen Lord is bound to a historical fact: an empty grave. Whoever desires to rejoice over the living Lord, but will not falteringly bow before the empty grave, is in danger of falling into an irrelevant subjective personalism. Personal reality (the risen and living Christ) and material reality (an empty grave) are both part of the truth of the resurrection as a salvific reality (De Jong 1967:70-99).

Since the resurrection is not only a new perspective, but should be considered as a historic reality, it has consequences for hope. The resurrection story can easily degenerate into merely a subjective longing for everlasting life. Resurrection hope then becomes hope for a collective existence. It can be reduced to a self-delusionary projection of the human longing for permanency. As a resurrection reality (the empty grave), hope is not merely a psychological projection, but based upon a historical revelation of God in creation, which affects the very core of death itself. God's revelation in the resurrection implies a re-creation of creation and opens up a new perspective for meaningful living in the now.

According to Smit (1983):

As in the New Testament, so this 'new life' or 'life of resurrection' must not be understood purely moralistically (as if the resurrection only offers additional power for greater legalistic and moral use), or understood purely mystically (as if the resurrection would estrange us from this life in all its concreteness and humanness), but as a new vision of all things, a new point of departure, a new root of understanding, a new perspective and a new meaning, but together with this also a new power, a new present reality, and new possibilities of existence. (p. 26)

The reality of the resurrection is a unique reality with its own distinctive evidence. As novum [a radical new divine act] of God, it is not a mere psychological or existential event in the subjective memory of human beings. Therefore, the verification of the resurrection does not lie on the level of existence, but in the new way in which God deals radically and victoriously with the whole of creation. The uniqueness of this act lies in its healing implications for both the existential and historical aspects of reality. It summons us to a strange kind of faith: whilst facing death, to hope points radically to the contrary. Death is not the full stop of life.

Faith in the resurrection implies that the reason for hope should not be founded in our anxiety about death and the expectation of a life thereafter. The Christian hope should not be the antithesis of anxiety. We do not hope because we are afraid of death. In terms of Christ's resurrection, we hope in spite of our anxiety. Therefore, theologically speaking, the only grounds for hope should be the faithfulness of God as exemplified and illustrated in the following theological markers:

• salvation, justification and Christ's mediatory work

• the overcoming of death by the resurrection of Christ

• the eternal value of our bodily existence in terms of Christ's resurrected body

• eschatology and the promise of a radical new future.

In the victory of the resurrection the kingdom of God, as a new eschatological reality, is mediated via the resurrected Christ, and guaranteed by the indwelling spirit as a 'deposit' for what we expect to become eventually. The victory of God over nothingness, over anxiety and death is essentially the only true grounds for hope. As a salvific and eschatological reality, this victory affects the whole cosmos in all its finiteness and nothingness. The creation sighs and groans with yearning. Whenever the bodily resurrection of Christ is ignored and salvation is 'spiritualised' in mystical terms, faith in the resurrection could easily become an idea founded by mere subjective speculation.

Little wonder that Ridderbos (1966:46) is convinced that Paul's eschatology is a Christo-eschatology and can be described as that which was done in Christ, through an act of God, as a fulfilment of his plan of salvation. Christ's death and resurrection form the all-encompassing departure point of eschatology, while the parousia and the doxa of God's kingdom become the all-encompassing focal point. The reality of the eschatology is a Christological reality. It refers to an act of God (in which the believer shares corporatively in Christ's mediatory work), as well as an act of the Holy Spirit (due to the indwelling presence of God in us and the whole of creation).

The cross and the resurrection, in their reciprocal interconnectedness unveil the basic motif of a Christian hope: God's faithfulness to his promises and his salvific acts within the historicity of both the cross and the resurrection. According to Fretheim (1984:111), hope thus emanates from the notion of the faithfulness of God: 'Through it all, God's faithfulness and gracious purposes remain constant and undiminished'. God's salvific will does not waver: his steadfast love endures forever (Fretheim 1984:124). The cross and resurrection confirm the veracity of God's faithfulness and the truth of the eschatological victory within this creaturely reality.

Pastoral hermeneutics in the light of resurrection faith

A hermeneutics of the resurrection reveals the following theological implications:

• In Christ, God's promises are fulfilled and creation is brought back to its purpose: communion with God, through doxa, praise and worship.

• In Christ's 'He has truly risen,' the accomplishment becomes a new promise and places the creation within the framework of a new reality: the eschatological salvation. It means life has been transformed radically: from anxiety to hope, from nothingness to eschatology, from death to resurrection.

• In terms of the resurrection of Christ, history becomes more than an evolutionary development, a human achievement or technological management. History becomes a teleological accomplishment: the healing of the whole of creation by the shalom [peace] of the coming kingdom of God.

Victory over death then refers to:

• faith and the salvation of the cross (perfectum)

• hope and the veracity of the resurrection (futurum)

• love and the sacramental meaning of daily life: the Christian life and daily experiences as an embodiment of God's grace and presence through restored relationships (the pneumatological praesens).

As the first fruits of the spirit, we possess a certain pledge, in the mode of hope, that God will create a new future. This certainty already transforms daily life into a doxology to God's eschatological kingdom rule. Resurrected life can be realised daily by the spirit in the forms of faith, hope, love and peace. The process of making resurrection life real finds expression daily in thanksgiving and praise. Wholeness in God's creation and healing in a pastoral hermeneutics now implies to accept one's new being in Christ, to love one another unconditionally and to embrace life with gratitude and thanksgiving.

Resurrection as theological principle in pastoral care

The resurrection has the following implications for a theology of pastoral care:

• It promises victory over death and instils a vivid hope in the midst of anxiety surrounding death.

• It enables us to become participators in the resurrection power and life, in the midst of struggle and suffering. Living in fellowship with God means to be empowered by the spirit to live and to become engaged in human relationships.

• It restores geborgenheid, trust in life, and provides security because it opens up a new hermeneutics, that is to experience the living God in every dimension of existence, as well as in the whole of the cosmos. Life becomes an opportunity to embody God's grace and to enflesh love.

'Resurrectionism': The danger of a theologia gloriae

Is it indeed true that the resurrection is a promise about an easy way out of the human predicament of human suffering and death? Is the Christian hope a kind of cheap exit from the reality of death and dying? Is hope merely artificial optimism?

A warning against the danger of a theologia gloriae [cheap and artificial triumphalism] is particularly relevant when dealing with the theme hope in suffering, and the attempt to develop a pastoral theology from an eschatological perspective. The impression can easily be given that hope creates a cheap optimism and superficial euphoria. If this is so, then a resurrection perspective in pastorate has taken the easy route out of the problem of suffering. A theology of resurrection does not inspire people to ignore their suffering: it seeks to encourage people in their struggle and urge them to find meaning in their suffering. It even underlines the tragedy of death and suffering in this world. 'Tragedy gives aesthetic form to a world palpably at odds with the world as we desire to view it' (Hall 1996:51). It challenges a theology based on opportunistic imperialism and affluence: cheap triumphalism, a theologia gloriae. Pastoral theology is deeply embedded in, and determined by the suffering Son of God (Figure 2).

When resurrection hope blends with a kind of cultic folkloric heroism and a New World optimism, a theology of the resurrection can easily fall prey to resurrectionism:

The resurrectionism that colors most forms of Christianity on the North American continent is a late adaptation of this longstanding tendency of Christian theology to remove the cross from the heart of God. (Hall 1993:96)

Hope is only hope in suffering, not a flight from suffering, nor an attempt to bypass suffering. The harsh reality of suffering remains an immanent critique against any hope that attempts to avoid tension, anxiety, despair and transience by resorting to defence mechanisms. Even as 'king' Christ was still the wounded Christ bearing the scores of suffering.

False triumphalism (Berkouwer 1954:194) easily leads to self-glorification and self-justification with no longer any reckoning with sin and guilt. On the contrary, genuine triumph is found in the confession of guilt and receiving victory through sola fide, sola gratia [faith and thanksgiving].

Hope and victory in suffering do not necessarily mean victory out of suffering. Rather, victory sometimes has to embrace the hope of not overcoming: that is, revealing the patient and long-suffering nature of hope.

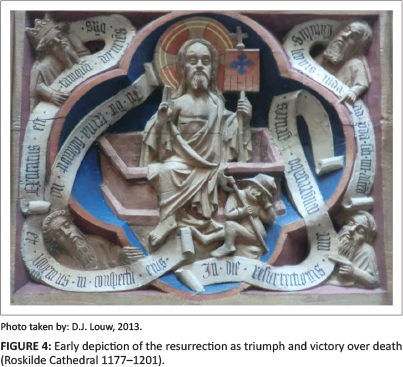

Resurrection hope does not imply an artificial optimism or a kind of false triumphalism. The latter can easily lead to self-glorification and self-justification with no longer any reckoning with the harsh realities of suffering, sin and guilt. On the contrary, genuine triumph is found in the confession of guilt and receiving victory through faith and thanksgiving. Human responsibility in suffering is indeed to live from the perspective of victory. This perspective leads, via the spirit, to struggle, patience and endurance. The evil power is dethroned and unmasked for its true identity: the anti-godly power of darkness. The evil power is overcome in principle: 'Death, where is your sting?' (Figure 3). But, despite this victory (Figure 4), these powers nevertheless remain real, and are not mere bogus powers. Grace should not become a 'cheap remedy' and be misused as a narcotic or anaesthetic to suppress human suffering, pain and existential anxiety.

Resurrection hope: The healing of life

A theology of the resurrection helps one to identify the following appropriate theological indicators for the healing of life:

• Transformation: the new reality within the reality of pain and destruction.

• Freedom and liberation: the experience of forgiveness and reconciliation.

• Vision, imagination and future: the motivating and driving force behind anticipation and expectation.

• Witness: the intention to reach out to others in their suffering and pain.

• Faithfulness: the guarantee for trust despite disorientation and disintegration.

• Support: edification within the koinonia [fellowship] of believers.

• Comfort: the courage to be, to endure and to accept.

• Truth: divine confirmation and a guarantee, promise for life.

• Hope as a new state of mind and being. Hope as a qualitative indication that in terms of the new eschatological reality in Christ, our new eschatological identity is an ontological fact: I am already a new creation in Christ.

Although the reality of the resurrection is accessible by faith and cannot be demonstrated by using historical methods of investigation, the validity of the resurrection is not even dependent on faith. The resurrection, as an act of God, is a revelatory category (sui generis), which remains linked to the empty grave and functions independently from any verification by faith. It reveals to us the new state and condition of our being: transformed by God. For its validation the new status is totally dependent on God's faithfulness.

The resurrection is not merely a promise: it is also fulfilment. As such, it embraces a new vision and promise which, as resurrection hope, aligns the believer towards a future which is concerned with Christ's parousia, God's kingdom rule and resurrection life (eternal life as fellowship with God). Through the cross and resurrection, the resurrection hope becomes a grounded hope, rooted in the grace of God. The atoning character of the cross and the resurrection is fundamental to the promissory character of the resurrection. The expected redemption (Rm 8:19) is founded in the atonement which has already been completed (2 Cor 5:19) (Klappert 1968:41). It opens up a new orientation towards the future: hope as the anticipation of God's fulfilled promises.

The resurrection confirms the eschatological dimension of hope which consists of the following dimensions:

• The dimension of perfectum: firmness and security (Christ died, arose, and we are raised together with him).

• The dimension of praesens: encounter and communion (through the spirit, we now live in fellowship with the risen and exalted Christ).

• The dimension of futurum: expectation and anticipation (eternal salvation, the bodily resurrection and God's all-encompassing rule: God is everything to everybody).

The practical implication of the perfectum, praesens and futurum of eschatology is the creativity of imagination. To recall the cross and the resurrection is to 'envisage' a new future. This vision challenges believers to use their imagination in order to practise hope and to enflesh love. Imagination is needed to start changing the social environment, to instil justice and to transform dehumanising structures.

Furthermore, the resurrection plays a fundamental role in the link between human reality of suffering and a divine intervention. It confirms the fact that Jesus Christ is indeed the Son of God. In fact, the resurrection is the only 'theological proof' that Christ was not merely a human being but indeed the Son of God. From a theological point of view one can even argue that the resurrection constitutes the divinity of Christ. According to Romans 1:4 Paul argues that Christ was declared and vindicated as the Son of God by his resurrection from the dead. Furthermore, due to the fact of the resurrection one can claim that Christ did not die the death of a martyr but the unique death of a mediator, vicariously for us, in our place.

The resurrection also confirms the fact that the atonement on the cross is an act of God. According to Moltmann's (1995) basic premise the resurrection functions as the founding factor and Realgrund - reality principle - for the cross. The cross functions as the principle of knowledge and Erkenntnisgrund - understanding - regarding God's intention. When the resurrection is viewed as a revelation of Jesus' divinity in his humanity, and thus allows a particular focus to fall on the divine mission of Jesus of Nazareth, it does not mean that the resurrection makes the earthly Jesus superfluous. It is a further confirmation of Christ's mediatory work as an act of the triune God.

Conclusion

What then is the impact of the fact that our salvation is a divine act and that the resurrection proves God's involvement in the reality of all existential forms of death on Christian spirituality and the human quest for meaning?

Kievit (1970:10) contends that for Calvin, Christian hope is no vague longing, but a definite and specific expectation. For Calvin, this hope is based on God's indubitable promises, on the covenant of grace, of which Christ is the mediator. Calvin regarded hope as the consequence of faith: that link of communion with Christ which enables humankind to receive grace, and which unlocks the future. Hope is the expectation of that which we already possess by faith (spes est expectatio earum rerum, quas in fide habemus). According to Calvin the hope for eternal salvation is thus an inseparable part of a living faith (Calvijn Inst. III, 2, 42:68)

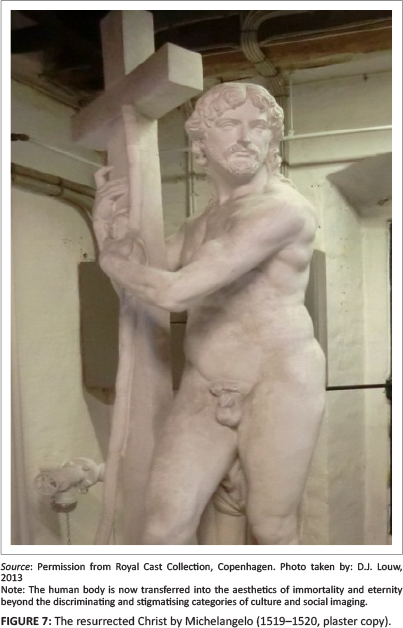

The Christian understanding of hope does not pretend to solve all problems in life: it does not pretend to give solutions, cheap answers or promises of prosperity and instant happiness. However, it provides a meaningful framework in order to proceed with life in terms of an enduring faith and courage to be parrhesia [existential boldness and spiritual empowerment]. The resurrection equips Christians to resist all kinds of forms of stigmatisation, discrimination and humiliation: resurrection leads to resistance, the resistance of evil and death. It killed all forms of dehumanising attitudes. It instils a radical new identity beyond the prejudice of culturally formed identities. Even in the gender discourse and HIV and AIDS debate, it can contribute to the rewriting of 'masculinity and health' beyond the biased categories of chauvinism, misogyny and homophobia (Meyer & Struthers 2012:6).

Resurrection is about establishing a new identity in Christ, the eschatological identity of a new being. It even overcomes the dualism between body and soul and incorporates embodiment as a vital ingredient of our new being in Christ and the vividness of resurrection hope. Dignity emanates from the hope of resurrection. Hope is not wishful thinking or any forecast about what is going to happen in future. Hope is a new state of being and of mind.

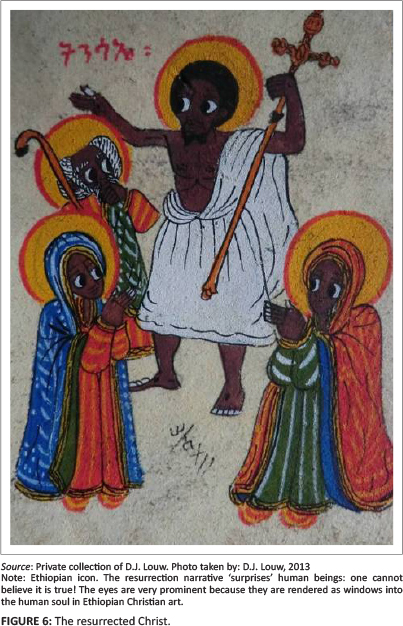

The power of the resurrection, however, does not lead to resignation and passivity. It can even make one rebellious and assists in one's struggle against suffering (Berkhof 1973:331) (Figure 5). Whilst a theologia gloriae is concerned with glorificari per opera - the glory of works (human achievements) - a theologia crucis is concerned with the confession of sins and a theologia resurrectionis with the resurrection hope. In terms of our future, the coming glory is a gloria in re which yet has to be unfolded in us. In the cross, this glory is already enveloped in a garment of hope - in spe. The gloria in spe is the gloria per crucem [through the cross]. The glory of the cross awakens hope. The resurrection is the reality and substance of this hope. Glorification is a paradox for the believer, because glorificatio in re actually means gloria per crucem. Now we already share in the glory of the victory, via the mediator (corporatively, in Christ), and via the counsellor (the indwelling Holy Spirit). Meaning exists within both suffering and peace. The eschatological reality inspires faith, and instils hope. Meaning in suffering then refers to the following two basic Christian and, therefore, spiritual entities: faith and hope. From an empirical perspective, the resurrection seems to be impossible, from the perspective of faith and hope, resurrection is a divine surprise and a theological exclamation mark (Figure 6).

If the assertion of W. Grab (2000) is indeed true that practical theology is about the history of different designs for life, that the religious dimension in an ecclesial praxis is the connection between the quest for meaning and the attempt to signify life (Grab 2006), my position is that a theologia resurrectionis provides pastoral theology of a paradigm that can contribute to the healing of life and the human attempt to signify life within the realm of suffering, death and dying.

It is due to the resurrection in Christ (Figure 7) that life attains meaning. From the perspective of the resurrection Paul assessed the value of his life. When he looked back in terms of what he did and how he prosecuted the church, his life was a failure, literally like a foetus that should have been aborted before birth (1 Cor 16:8). From the perspective of the resurrection his life is 'beautiful': 'But by the grace of God I am what I am' (1 Cor 15:9). The 'what' of his life is now determined not by 'doing functions' but by 'being functions' (the eschatological ontology of a new creation): 'Therefore, if anyone is in Christ, he is a new creation' (2 Cor 5:17).

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationship(s) that may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

References

Augsburger, D., 1986, Pastoral counselling across cultures, The Westminster Press, Philadelphia. [ Links ]

Barth, K., 1953, Die Lehre von der Versohnung, EVZ, Zollikon-Zürich. [ Links ]

Berkhof, H., 1973, Christelijkgeloof, Callenbach, Nijkerk. [ Links ]

Berkouwer, G.C., 1954, De triomf der genade in de theologie van Karl Barth, Kok, Kampen. [ Links ]

Berkouwer, G.C., 1961, De wederkomst van Christus I, Kok, Kampen. [ Links ]

Bloch, E., 1970, Tubinger Einleitung in die Philosophie, Band 13, Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main. [ Links ]

Brunner, E., 1953, Das Ewige als Zukunft und Gegenwart, Zwingli Verlag, Zürich. [ Links ]

Buhr, M., 1960, ,Kritische Bemerkungen zur E. Bloch's Hauptwerk "Das Prinzip Hoffnung"', Deutsche Zeitschriftfur Philosophie8(4),365-379. [ Links ]

Calvijn, J., n.d., Institutie, vertl. A. Sizoo, 8e druk, Meinema, Delft. [ Links ]

Campbell, C.L. & Cilliers, J.H., 2012, Preaching fools. The gospel as a rhetoric of folly, Baylor University Press, Waco. [ Links ]

Camus, A., 1965, The myth of Sisyphus, Hamish Hamilton, London. [ Links ]

Capps, D., 1990, Reframing a new method in pastoral care, Fortress Press, Minneapolis. [ Links ]

Davies, O., 2003, A theology of compassion. Metaphysics of difference and the renewal of tradition, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

De Jong, J.M., 1967, De opstanding van Christus. Geloof en natuurwetenschap 2, Boekencentrum, Gravenhage. [ Links ]

Edmaier, A., 1968, Horizonte der Zukunft. Eine philosophische Studie, Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburs. [ Links ]

Fretheim, T.E., 1984, The suffering of God, Fortress, Philadelphia. [ Links ]

Gesche, A., 1973, Die Auferstehung Jesu in der dogmatischen Theologie. Theologische Bericht2, Benziger, Zürich. [ Links ]

Guthrie, D., 1981, New testament theology, Inter-Varsity, Leicester. [ Links ]

Goppelt, L., 1980, Theologie des Neuen Testaments, 3rd edn., Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, Göttingen. [ Links ]

Gräb, W., 2000, Lebensgeschichten, Lebensentwurfe, Sinndeutungen, Kaiser Gutersloher Verlagshaus, Gütersloh. [ Links ]

Gräb, W., 2006, Sinnfragen. Transformationene des Religiosen in der modernen Kultur, Kaiser Gutersloher Verlagshaus, Gütersloh. [ Links ]

Hall, D.J., 1993, Professing the faith. Christian theology in a North American context, Fortress Press, Minneapolis. [ Links ]

Hall, G.G., 1996, 'Suffering and Tragedy', in P. McEnhill G.B. & Hall (eds.), The presumption of presence: Christ, church and culture in the academy: Essays in honour of D.W.D. Shaw, pp. 48-58, Edinburgh, Scottish Academic Press. [ Links ]

Jonker, H., 1983, Theologische Praxis, Callenbach, Nijkerk. [ Links ]

Kierkegaard, S., 1967, The concept of dread, Princeton University Press, Princeton. [ Links ]

Kievit, I., 1970, Leven van de hoop, Kok, Kampen. [ Links ]

Klappert, B., 1968, Diskussion um Kreuz und Auferstehung, 3rd edn., Aussaat, Wuppertal. [ Links ]

Landman, C., 2009, Township spiritualities and counseling, Unisa Research Institute for Theology and Religion, Pretoria Duplicating Company, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Lekkerkerker, A,F.N., 1966, Het evangelie van de versoening, Bosch, Baarn. [ Links ]

Marcel, G., 1962, Homo viator. Introduction to metaphysics of hope, Harper & Row, London/Chicago. [ Links ]

Meyer, M. & Struthers, H., 2012, (Un)covering men. Rewriting masculinity and health in South Africa, Fanele, Sunnyside. [ Links ]

Moltmann, J., 1995, Das kommen Gottes: Christliche Eschatologie, Chr. Kaiser/ Gütersloher Verlagshaus, Gütersloh. [ Links ]

Moltmann, J., 1966, Theologie der Hoffnung: Untersuchungen zur Begründung und zu den Konsequenzen einer christlichen Eschatologie, 5th edn., Kaiser, München. [ Links ]

Nauer, D., 2010, Seelsorge. Sorge um die Seele, Verlag W. Hohlhammer, Stuttgart. [ Links ]

Ott, H., 1972, Die Antwort des Glaubens, Kreuz, Berlin. [ Links ]

Polak, F.L., 1968, Prognostica. Wordende wetenschap schouwt en schept de toekomst, A. E. Kluwer, Deventer. [ Links ]

Ridderbos, H., 1966, Paulus: Ontwerp van zijn theologie, Kok, Kampen. [ Links ]

Sartre, J-P., 1943, L'Être et le Néante, Gallimard, Paris. [ Links ]

Schütz, P., 1963, Freiheit - Hoffnung - Prophetie: Von der Gegenwirtigkeit des Zukünftigen, Furche Verlag, Hamburg. [ Links ]

Simon, U.E., 1967, A theology of Auschwitz, Gollancz, London. [ Links ]

Smit, D.I., 1983, 'Prediking in die paastyd', in C.W. Burger, B.A. Muller & D.J. Smit (reds.), Riglyne Vir paas-, hemelvaarts- en pinksterprediking, bl. 10-30, Kaapstad, NG Kerk-Uitgewers. (Woord teen die Lig 3). [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Daniel Louw

Faculty of Theology

171 Dorp Street 171

Stellenbosch 7600

South Africa

Email:djl@sun.ac.za

Received: 20 June 2013

Accepted: 29 Nov. 2013

Published: 14 Apr. 2014